Bilateral colobomatous microphthalmos with orbital cyst is a rare congenital anomaly.1,2,3 It arises between the sixth to seventh weeks of gestation, is usually isolated, and can be either unilateral or bilateral. Association with systemic anomalies may occur, and the involvement of chromosomes 3, 5, 13, 18 and 22 has been reported.3

Here, we describe a newborn presenting with bilateral colobomatous microphthalmos with a right orbital cyst. After excision of the cyst, histopathology of the cyst wall was performed and several biochemical parameters of its fluid content were evaluated.

Case report

A newborn presented with bilateral microphthalmos. She was the product of a pregnancy complicated by vitamin A deficiency, documented from at least week 16 to week 24 of gestation, after previous gastric bypass surgery in her 32‐year‐old mother.

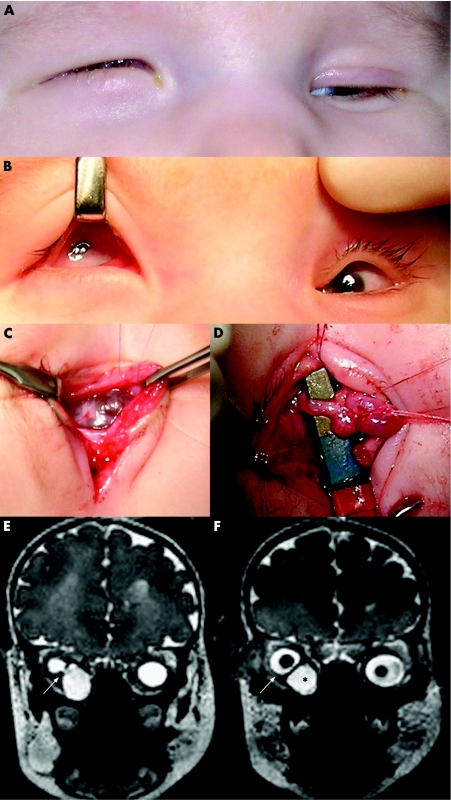

Clinical examination of the newborn showed bilateral microphthalmos. At the right side, a small eye was displaced upwards by a large cyst (fig 1A, B). The cornea with a diameter of 3 mm was diffusely cloudy. A circular pupil and some pupillary membrane remnants were observed. At the left side, microphthalmos was much less pronounced. Some retinal blood vessels were observed in both eyes on fundoscopy.

Figure 1 (A) External appearance of newborn with bilateral colobomatous microphthalmos with right orbital cyst. Note the bluish bulge in the right lower eyelid; (B) preoperative presentation of both eyes; (C) peroperative dissection of right orbital cyst; (D) intraoperative view of connective stalk between cyst and right microphthalmic eye; (E, F) Orbital T2‐weighted magnetic resonance imaging shows bilateral microphthalmos and large cyst in right orbit; (E) coronal view, demonstrating a connective stalk between microphthalmic eyeball and cyst (arrow); (F) coronal view, showing hyperintense cystic mass (black asterisk) causing superotemporal displacement of right microphthalmic eye (arrow).

Ultrasonography confirmed bilateral microphthalmos with chorioretinal coloboma and a right‐sided adjacent orbital cyst. Magnetic resonance imaging disclosed the exact location and extent of the cyst (fig 1E, F).

Subsequent management was to keep the cyst for as long as necessary to ensure adequate socket size. However, progressive right lower eyelid inversion led to conjunctival maceration. Excision of the cyst with ligation of the connecting stalk was performed, saving the right microphthalmic eye itself (fig 1C, D).

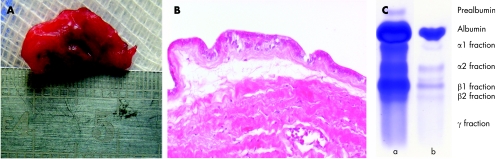

Histopathologically, the cyst wall was composed of two layers (fig 2A, B). The outer layer contained dense fibrous tissue with some normal blood vessels, resembling normal sclera. The inner layer was one of dysplastic retinal tissue, which consisted of cylindrical, neuroectodermal‐like cells with an eosinophylic cytoplasm showing some nuclear stratification. Immunohistochemistry showed no reactivity against cytokeratins 5, 6, 7 and 20. Consequently, the epithelium was not of an adenomatous type. The cylindrical cells of the inner layer stained diffusely and intensely for CD56 (neural cell adhesion molecule), confirming their neuroectodermal origin.

Figure 2 (A) Excised orbital cyst; (B) haematoxylin and eosin‐stained section of cyst wall (at magnification ×200), demonstrating the inner layer of neuroectodermal‐like cylindrical cells without any organisation, and outer layer of dense fibrous tissue; (C) electrophoresis of (a) cyst fluid and (b) serum sample as negative control.

Electrophoresis of cyst fluid produced a pattern almost identical to cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) (fig 2C). β‐Trace protein (EC 5.3.99.2), a highly sensitive and specific CSF marker, and cystatin C were quantified with a Behring Nephelometer II (Dade Behring, Germany). β‐Trace protein concentration was 32.7 mg/l, whereas cystatin C concentration was 2.4 mg/l. The concentration of hyaluronic acid was less than 2 mg/l. Additionally, total protein concentration was 780 mg/l as measured by a pyrogallol red method (table 1).

Table 1 Comparison of concentration of several biochemical parameters between cyst fluid, cerebrospinal fluid and serum.

| Cyst fluid | Cerebrospinal fluid (reference range) | Serum (reference range) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| β‐Trace protein (mg/l) | 32.7 | 5.4–23.8 | 0.2–0.72 |

| Cystatin C (mg/l) | 2.4 | 1.2–4.2 | 0.53–0.95 |

| Hyaluronic acid (mg/dl) | <2 | <0.1 | <0.1 |

| Total protein concentration (mg/l) | 780 | 150–450 | 60 000–80 000 |

Comment

Gastric bypass as treatment for morbid obesity has been shown to carry a considerable risk of nutritional deficiencies, which may lead to retinal dysfunction.4 In this case, ocular development occurred in the context of a documented vitamin A deficiency during the initial weeks of pregnancy. Such deficiency is also known to disrupt ocular development in both animals and humans.5,6

Little is known about the exact nature and origin of the fluid in an orbital cyst associated with microphthalmos. In order to identify the origin of the cyst, several of its parameters were evaluated. The cyst fluid sample produced an electrophoretic pattern identical to a CSF sample, including a typical band of prealbumin. To further corroborate this finding, we assessed the β‐trace protein content of the cyst fluid. β‐Trace protein, aka prostaglandin D2 (PGD2) synthase, is bifunctional, acting as a PGD2‐producing enzyme and as an intercellular transporter of retinoids or other lipophilic substances.7 This enzyme is produced mainly in the epithelial cells of the choroidal plexus, in the leptomeninges, and to a lesser extent in oligodendrocytes, after which it is secreted into the CSF. It was introduced by Felgenhauer et al as a marker for liquorrhoea because its concentration in normal CSF is 35‐fold higher than in serum.8 Nephelometric β‐trace protein detection is rapid and highly valid for the diagnosis of a CSF leak (sensitivity ranging from 93% to 100%, specificity of 100%, negative predictive value 0.971, positive predictive value 1).9,10 The concentration of β‐trace protein in the cyst fluid was found to be far above the upper reference limit for CSF. It is as yet unclear what the exact role of this protein may be in the cyst fluid. But it is hypothesised that neuroectodermal cells lining the cyst wall shed β‐trace protein in the cyst cavity.

In conclusion, the histopathological findings, the CSF‐like electrophoresis and the high concentration of β‐trace protein in the cyst fluid are strong arguments in favour of a neuroectodermal origin of the orbital cyst associated with colobomatous microphthalmos.

Footnotes

Competing interests: None declared.

References

- 1.Lieb W, Rochels R, Gronemeyer U. Microphthalmos with colobomatous orbital cyst: clinical, histological, immuno‐histological and electromicroscopic findings. Br J Ophthalmol 19907459–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arstikaitis M. A case report of bilateral microphthalmos with cyst. Arch Ophthalmol 196982480–482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kurbasic M, Jones F V, Cook L N. Bilateral microphthalmos with colobomatous orbital cyst and de‐novo balanced translocation t(3;5). Ophthalmic Genet 200021239–242. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Spits Y, De Laey J J, Leroy B P. Rapid recovery of night blindness due to obesity surgery after vitamin A repletion. Br J Ophthalmol 200488583–585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cools M, Duval E L I M, Jespers A. Adverse neonatal outcome after maternal biliopancreatic diversion operation: report of 9 cases. Eur J Pediatr 2006165199–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dickman E D, Thaller C, Smith S M. Temporally‐regulated retinoic acid depletion produces specific neural crest, ocular and nervous system defects. Development 19971243111–3121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tanaka T, Urade Y, Kimura H.et al Lipocalin‐type prostaglandin D synthase (β‐trace) is a newly recognized type of retinoid transporter. J Biol Chem 199727215789–15795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Felgenhauer K, Schädlich H J, Nekic M. β–trace protein as marker for cerebrospinal fluid fistula. Klin Wochenschr 198765764–768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Risch L, Lisec I, Jutzi M.et al Rapid, accurate and non‐invasive detection of cerebrospinal fluid leakage using combined determination of β‐trace protein in secretion and serum. Clin Chim Acta 2005351169–176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bachmann G, Petereit H, Djenabi U.et al Predictive values of β‐trace protein (prostaglandin D synthase) by use of laser‐nephelometry assay for the identification of cerebrospinal fluid. Neurosurgery 200250571–577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]