A 38‐year‐old Hispanic man presented with painless decreased vision in his right eye for 7 days. He had had no light perception with his left eye for 7 years, for which he was unable to provide a history. Visual acuity was 20/70 in the right eye (OD) and no light perception in the left eye (OS), with normal pressures in both eyes (OU). Slit‐lamp examination showed an unremarkable OD, but disclosed a glaucoma‐implant tube in a formed anterior chamber in the left eye, with posterior synechiae of the iris and a white cataract. Ophthalmoscopy of the right eye showed a superotemporal branch retinal vein occlusion with an associated serous retinal detachment involving the macula, without vitreous cell. The optic nerve and the remaining vessels and periphery were unremarkable. There was no view to the fundus in the left eye.

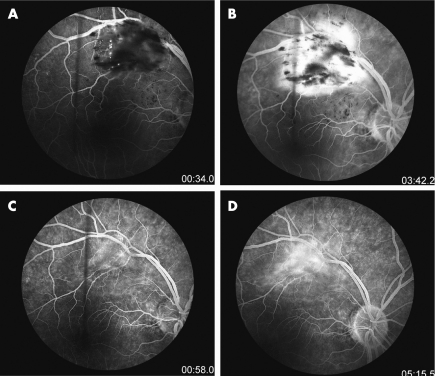

Echography of the right eye did not show choroidal thickening, and in the left eye, revealed a funnel retinal detachment. Fluorescein angiogram of the right eye showed blockage corresponding to areas of haemorrhage and exudation and late leakage, with no evidence of vasculitis.

Serological and medical examination showed no evidence of diabetes mellitus, systemic hypertension, sarcoidosis or toxoplasma, toxocara, HIV or syphilis infection. Chest x ray was normal, but the purified protein derivative test for tuberculosis was positive at 10 mm of induration. Bartonella henselae titres were equivocal at 1:128 IgG, IgM negative, a level at which 13% of uninfected individuals can have titres.1 At this point, the patient refused an anterior chamber tap for analysis of tuberculosis, and a presumptive diagnosis of bartonella retinitis was made. As several cases of bartonella infections have been reported to resolve without treatment, it was decided to observe the patient while also ruling out a hypercoaguable aetiology.2 An extensive hypercoaguability examination was non‐contributory.

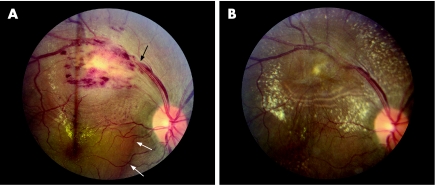

Over 8 weeks of observation, the subretinal fluid and vein occlusion worsened clinically, and visual acuity fluctuated between 20/70 and 20/400 OD. Repeated Bartonella titres 6 weeks after the original titres remained at 1:128 IgG, IgM negative. At this point, the patient again deferred anterior chamber paracentesis. Given the failure of the fundus findings to resolve, or Bartonella titres to increase, empirical isoniazid treatment was started. A medicine consultation deferred four‐drug treatment on the basis of a positive PPD being the only direct evidence of tuberculosis. At 4 weeks after beginning isoniazid, visual acuity improved to 20/30, with marked resolution of the serous detachment. A medicine consultation was again sought but four‐drug treatment was deferred on similar grounds. After 10 weeks on isoniazid treatment, visual acuity was 20/25, with no subretinal fluid on optical coherence tomography. Repeat fluorescein angiogram (fig 1) was negative for any vasculitic process. Colour fundus photos (fig 2) showed subtle lines at the level of the retinal pigment epithelium outside the superior arcades, indicating the furthest extent of the subretinal fluid.

Figure 1 (A,B) Early and late phase fluorescein angiograms (FA) of the right eye before treatment. Note the lack of staining of vessel walls and diffuse leakage only on late FA. (C,D) Early and late phase FA after 4 weeks of isoniazid treatment. No staining of vessel walls is observed. Mild diffuse late leakage is still present.

Figure 2 Colour fundus photo of the right eye at presentation (A) and after 4 weeks of isoniazid treatment (B). The black arrow indicates an arteriovenous crossing and likely site of occlusion. The two white arrows mark the nasal border of the serous retinal detachment.

Comment

Ocular tuberculosis is regarded as a rare manifestation of tuberculosis infections, historically occurring in only 1.46% of patients with systemic disease.3 Vein occlusions have been described previously with ocular tuberculosis; however, in the absence of any evidence of vasculitis, vitritis or uveitis, this is a rare presentation.4 Mechanistically, the vein occlusion could have been the result of compression from a retinal or choroidal tubercle. The presence of retinal pigment epithelial changes argues for a deep retinal or choroidal process. Although a focal area of vasculitis obscured by retinal exudation could also be responsible, the lack of any vitreous cell argues against this.

In the absence of an anterior chamber or vitreous sample for culture or polymerase chain reaction analysis, only a presumptive diagnosis can be made. However, an extensive investigation ruled out any other infectious, systemic (including diabetes and hypertension), or hypercoaguable aetiology. Furthermore, marked clinical improvement was achieved rapidly after the onset of anti‐tuberculosis treatment. The failure of the patient's IgG Bartonella titres to increase, or IgM positivity to develop, despite two separate tests separated by 6 weeks, greatly lessens the likelihood of this aetiology.1 In summary, we report an unusual presentation of presumed ocular tuberculosis in the setting of a branch retinal vein occlusion without associated vasculitis or evidence of intraocular inflammation. This case highlights the need for the pursuit of a systemic aetiology of vein occlusions in otherwise healthy, young individuals.

Footnotes

Competing interests: None.

References

- 1.Sander A, Berner R, Reuss M. Serodiagnosis of cat scratch disease: response to Bartonella henselae in children and a review of diagnostic methods. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis 200120392–401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Solley W A, Martin D, Newman N.et al Cat sratch disease: posterior segment manifestations. Ophthalmol 19991061546–1553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Donahue H C. Ophthalmologic experience in a tuberculosis sanatorium. Am J Ophthalmol 196764742–748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gupta A, Gupta V, Arora S.et al PCR‐Positive tubercular retinal vasculitis: clinical characteristics and management. Retina 200121435–444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]