Abstract

Background

Pigment epithelium‐derived factor (PEDF), a glycoprotein with potent neuronal differentiating activity, was recently found to inhibit advanced glycation end product (AGE)‐induced retinal hyperpermeability and angiogenesis through its antioxidative properties, suggesting that it may exert beneficial effects on diabetic retinopathy by acting as an endogenous antioxidant. However, the inter‐relationship between PEDF and total antioxidant capacity in the eye remains to be elucidated.

Aims

To determine vitreous PEDF and total antioxidant levels in patients with proliferative diabetic retinopathy (PDR), and to investigate the relationship between them.

Methods

Vitreous levels of PEDF and total antioxidant capacity were measured by an ELISA in 39 eyes of 36 patients with diabetes and PDR and in 29 eyes of 29 controls without diabetes.

Results

Vitreous levels of total antioxidant capacity were significantly lower in patients with diabetes and PDR than in controls (mean (SD) 0.16 (0.05) vs 0.24 (0.09) mmol/l, respectively, p<0.001). PEDF levels correlated positively with total antioxidant status in the vitreous of patients with PDR (r = 0.37, p<0.05) and in controls (r = 0.41, p<0.05). Further, vitreous levels of PEDF in patients with PDR without vitreous haemorrhage (VH(−)) were significantly (p<0.05) decreased, compared with those in the controls or in patients with PDR with vitreous haemorrhage (VH(+); PDR VH(−), 4.5 (1.1) μg/ml; control, 7.4 (4.1) μg/ml; PDR VH(+) 8.5 (3.6) μg/ml).

Conclusion

This study demonstrates that PEDF levels are associated with total antioxidant capacity of vitreous fluid in humans, and suggests that PEDF may act as an endogenous antioxidant in the eye and could play a protective role against PDR.

Pigment epithelium‐derived factor (PEDF) is a glycoprotein that belongs to the superfamily of serine protease inhibitors. It was first purified from conditioned medium of human retinal pigment epithelial cells as a factor with potent neuronal differentiating activity.1 Recently, PEDF has been shown to be a highly effective inhibitor of angiogenesis in cell culture and animal models. PEDF inhibits the growth and migration of cultured endothelial cells, and it potently suppresses ischaemia‐induced retinal neovascularisation.2,3 PEDF levels in aqueous or vitreous humour are decreased in patients with diabetes, especially those with proliferative retinopathy (PDR).4,5,6 These observations suggest that the loss of PEDF activity in the eye may contribute to the pathogenesis of PDR.

We have previously shown that advanced glycation end products (AGEs), senescent macroprotein derivatives formed at an accelerated rate in diabetes, elicit oxidative stress and induce vascular inflammation in the eye, thereby being involved in the pathogenesis of PDR.7,8,9 Recently, PEDF was reported to inhibit the AGE‐signalling pathway to retinal hyperpermeability and angiogenesis by suppressing the generation of reactive oxygen species and subsequent overexpression of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF).7,8,9 In addition, we have found that vitreous levels of both AGEs and VEGF are significantly higher in patients with diabetes than in controls, and that their levels are increased in association with the severity of neovascularisation in diabetic retinopathy.10 We also found in the previous study that vitreous levels of AGEs and VEGF correlated with each other and that both factors were inversely associated with the total antioxidant status in the vitreous fluid of controls without diabetes and patients with diabetic retinopathy.10 These observations suggest the active participation of oxidative stress in the pathogenesis of PDR, and that PEDF may exert beneficial effects on PDR by acting as an endogenous antioxidant in the eye. However, the inter‐relationships between vitreous levels of PEDF and antioxidant status in patients with diabetes and retinopathy remain to be elucidated.

In this study, we used an ELISA to determine PEDF and total antioxidant levels in the vitreous fluid of patients with diabetic retinopathy, and investigated the relationship between them.

Patients and methods

Patients

This study involved 36 patients with diabetes (21 men and 15 women) with PDR with a mean (SD) age of 52 (12) years. Their known duration of diabetes was 10 (7.7) years and the mean (SD) current level of glycated haemoglobin (HbA1c) was 6.7% (1.4%). The diagnosis of diabetes was made by the criteria of the American Diabetes Association reported in 1997. According to the previous report published by Guidry et al,11 we divided patients with PDR into two groups: patients with PDR with vitreous haemorrhage (VH(+); n = 32 eyes) and patients with PDR without vitreous haemorrhage (VH(−); n = 7 eyes). A total of 29 patients without diabetes (6 men and 23 women, mean (SD) age 63 (8.4) years) with idiopathic macular hole or epiretinal membrane served as controls. The study protocol was approved by our institutional ethics committees. Informed consent was obtained from all subjects.

Measurement of vitreous levels of PEDF and antioxidant capacity

Undiluted vitreous samples were obtained during therapeutic vitrectomy from 39 eyes of patients with PDR and 29 control eyes . These specimens were collected in sterile tubes and stored at −80°C until use. Vitreous levels of PEDF and antioxidant capacity were measured with ELISA, as described previously.10,12 Interassay (n = 17) and intra‐assay (n = 14) coefficients of variation of the ELISA were 4.7% and 7.3%, respectively. Recovery of the added recombinant PEDF in serum samples was 94.2% (1.7%). The assay linearity was shown to be intact with serial dilution of serum. We also confirmed the specific interaction between the PEDF antibody used for the ELISA and PEDF in the samples with western blot analysis.12

Statistical analysis

Data were expressed as mean (SD). Statistical significance was evaluated using the Mann–Whitney U test for paired comparison. Pearson's correlation coefficient test was used for analysis of the correlation between PEDF levels and total antioxidant capacity in the vitreous fluid of patients with PDR, and Spearman's correlation coefficient by rank test for analysis of the data in controls. A p value <0.05 was considered to be significant.

Results

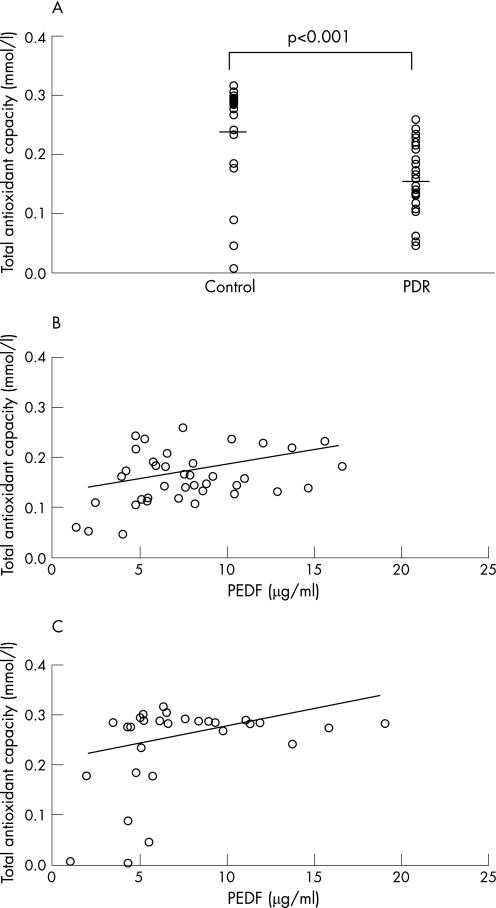

Total antioxidant status in the vitreous humour was decreased in patients with PDR compared with controls (0.16 (0.05) vs 0.24 (0.09) mmol/l, respectively, p<0.001; fig 1A). There was no significant difference in total antioxidant capacity in the vitreous fluid between patients with PDR with and without vitreous haemorrhage (0.17 (0.05) vs 0.13 (0.05) mmol/l, respectively). Further, when we classified the patients with PDR into two groups, a satisfactorily treated group with panretinal photocoagulation (n = 16) and an insufficiently treated group (no or focal retinal photocoagulation; n = 23), there was no significant difference in vitreous total antioxidant capacity between them (0.17 (0.05) vs 0.15 (0.05) mmol/l, respectively). In addition, there was no significant correlation between the vitreous total antioxidant status and HbA1c levels (data not shown). As shown in fig 1B and C, total antioxidant status in the vitreous fluid correlated positively with vitreous levels of PEDF in patients with PDR (r = 0.37, p<0.05) and in controls (r = 0.41, p<0.05).

Figure 1 (A) Total antioxidant capacity of the vitreous fluid of patients with proliferative diabetic retinopathy (PDR) and controls without diabetes. Lines show mean values. Vitreous total antioxidant capacity was significantly lower in patients with diabetes and PDR than in controls (0.16 (0.05) vs 0.24 (0.09) mmol/l, respectively, p<0.001). Scatter plots of vitreous pigment epithelium‐derived factor (PEDF) levels versus total antioxidant capacity in patients with PDR (B) and in controls without diabetes. (C) PEDF levels correlated positively with total antioxidant status in the vitreous fluid of patients with PDR (r = 0.37, p<0.05; B) and in the controls (r = 0.41, p<0.05; C).

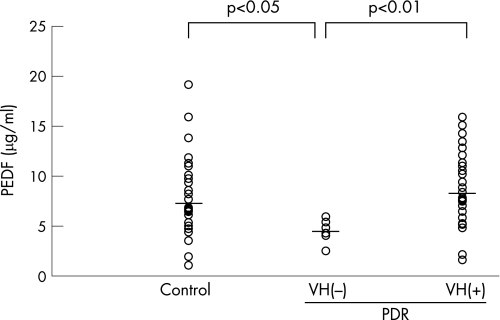

Vitreous PEDF levels in patients with PDR were not different from those in the controls (7.8 (3.7) vs 7.4 (4.1) μg/ml, respectively). However, vitreous levels of PEDF in patients with PDR without vitreous haemorrhage were significantly decreased compared with those in the controls or in patients with PDR with vitreous haemorrhage (PDR VH(−), 4.5 (1.1) μg/ml; control, 7.4 (4.1) μg/ml; PDR VH(+) 8.5 (3.6) μg/ml; fig 2).

Figure 2 Vitreous levels of pigment epithelium‐derived factor (PEDF) in the controls, in patients with proliferative diabetic retinopathy (PDR) without vitreous haemorrhage (VH(−)) and in patients with PDR with vitreous haemorrhage (VH(+)). Lines show mean values. Vitreous PEDF levels in PDR with VH(−) were significantly lower than those in the controls (4.5 (1.1) vs 7.4 (4.1) μg/ml, respectively, p<0.05) or in patients with PDR with VH(+) (4.5 (1.1) vs 8.5 (3.6) μg/ml, respectively, p<0.01).

Discussion

In the present study, we demonstrated for the first time that total antioxidant status in the vitreous fluid in patients with PDR was significantly decreased compared with controls without diabetes, and that vitreous levels of PEDF and total antioxidant capacity correlated positively with each other both in patients with PDR and in controls without diabetes. We have previously found that vitreous levels of AGEs and VEGF correlate with each other, both of which are inversely associated with vitreous total antioxidant capacity in patients with diabetic retinopathy.10 Further, PEDF is reported to inhibit the AGE‐signalling pathway to overexpression of VEGF through its antioxidant properties.8 These findings suggest that PEDF may act as an endogenous antioxidant in the eye and could play a protective role against PDR by counteracting the AGE–VEGF axis.

In this study, although PEDF levels in the vitreous fluid of patients with PDR with vitreous haemorrhage were not decreased, vitreous levels of PEDF in patients with PDR without vitreous haemorrhage were significantly lower than those in the controls. These findings are consistent with previous reports showing that vitreous levels of PEDF were decreased in diabetic retinopathy, especially in PDR.4,5 Contamination of PEDF by circulating blood may affect the vitreous levels of PEDF in patients with PDR with vitreous haemorrhage. Oxidative stress generation may be involved in retinal PEDF downregulation in diabetic retinopathy because AGEs or H2O2 suppress PEDF gene expression in microvascular endothelial cells, and an antioxidant, N‐acetylcysteine, restores the high‐glucose‐induced decrease in PEDF gene expression in cultured retinal pericytes.8,13,14 Moreover, intravenous administration of AGEs induces oxidative stress and subsequently decreases retinal PEDF expression as well.8 These observations suggest that decreased retinal PEDF levels in diabetic retinopathy further enhance oxidative stress generation in the eye, thus exacerbating diabetic retinopathy. Taken together, our present study suggests that vitreous levels of PEDF may be one of the biomarkers of oxidative stress in the eye and pharmacological upregulation or substitution of PEDF may offer a novel therapeutic strategy for the treatment of PDR.

Abbreviations

AGE - advanced glycation end product

PEDF - pigment epithelium‐derived factor

PDR - proliferative diabetic retinopathy

VEGF - vascular endothelial growth factor

Footnotes

Competing interests: None declared.

References

- 1.Tombran‐Tink J, Chader C G, Johnson L V. PEDF: pigment epithelium‐derived factor with potent neuronal differentiative activity. Exp Eye Res 199153411–414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dawson D W, Volpert O V, Gillis P.et al Pigment epithelium‐derived factor: a potent inhibitor of angiogenesis. Science 1999285245–248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Duh E J, Yang H S, Suzuma I.et al Pigment epithelium‐derived factor suppresses ischemia‐induced retinal neovascularization and VEGF‐induced migration and growth. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 200243821–829. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Spranger J, Osterhoff M, Reimann M.et al Loss of the antiangiogenic pigment epithelium‐derived factor in patients with angiogenic eye disease. Diabetes 2002502641–2645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ogata N, Tombran‐Tink J, Nishikawa M.et al Pigment epithelium‐derived factor in the vitreous is low in diabetic retinopathy and high in rhegmatogenous retinal detachment. Am J Ophthalmol 2001132378–382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Boehm B O, Lang G, Volpert O.et al Low content of the natural ocular anti‐angiogenic agent pigment epithelium‐derived factor (PEDF) in aqueous humor predicts progression of diabetic retinopathy. Diabetologia 200346394–400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yamagishi S, Imaizumi T. Diabetic vascular complications: pathophysiology, biochemical basis and potential therapeutic strategy. Curr Pharm Des 2005112279–2299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yamagishi S, Nakamura K, Matsui T.et al Pigment epithelium‐derived factor inhibits advanced glycation end product‐induced retinal vascular hyperpermeability by blocking reactive oxygen species‐mediated vascular endothelial growth factor expression. J Biol Chem 200628120213–20220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yamagishi S, Matsui T, Nakamura K.et al Pigment epithelium‐derived factor (PEDF) prevents diabetes‐ or advanced glycation end products (AGE)‐elicited retinal leukostasis. Microvasc Res 20067286–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yokoi M, Yamagishi S I, Takeuchi M.et al Elevations of AGE and vascular endothelial growth factor with decreased total antioxidant status in the vitreous fluid of diabetic patients with retinopathy. Br J Ophthalmol 200589673–675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Guidry C, Feist R, Morris R.et al Changes in IGF activities in human diabetic vitreous. Diabetes 2004532428–2435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yamagishi S, Adachi H, Abe A.et al Elevated serum levels of pigment epithelium‐derived factor in the metabolic syndrome. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2006912447–2450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yamagishi S, Matsui T, Inoue H. Inhibition by advanced glycation end products (AGEs) of pigment epithelium‐derived factor (PEDF) gene expression in microvascular endothelial cells. Drugs Exp Clin Res 200531227–232. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Amano S, Yamagishi S, Inagaki Y.et al Pigment epithelium‐derived factor inhibits oxidative stress‐induced apoptosis and dysfunction of cultured retinal pericytes. Microvasc Res 20056945–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]