Abstract

Engagement of α–β T cell receptors (TCRs) induces many events in the T cells bearing them. The proteins that transduce these signals to the inside of cells are the TCR-associated CD3 polypeptides and ζ–ζ or ζ–η dimers. Previous experiments using knockout (KO) mice that lacked ζ (ζKO) showed that ζ is required for good surface expression of TCRs on almost all T cells and for normal T cell development. Surprisingly, however, in ζKO mice, a subset of T cells in the gut of both ζKO and normal mice bore nearly normal levels of TCR on its surface. This was because ζ was replaced by the FcɛRI γ (FcRγ). These cells were relatively nonreactive to stimuli via their TCRs. In addition, a previous report showed that ζ replacement by the FcRγ chain also might occur on T cells in mice bearing tumors long term. Again, these T cells were nonreactive. To understand the consequences of ζ substitution by FcRγ for T cell development and function in vivo, we produced ζKO mice expressing FcRγ in all of their T cells (FcRγTG ζKO mice). In these mice, TCR expression on immature thymocytes was only slightly reduced compared with controls, and thymocyte selection occurred normally and gave rise to functional, mature T cells. Therefore, the nonreactivity of the FcRγ+ lymphocytes in the gut or in tumor-bearing mice must be caused by some other phenomenon. Unexpectedly, the TCR levels of mature T cells in FcRγTG ζKO mice were lower than those of controls. This was particularly true for the CD4+ T cells. We conclude that FcRγ can replace the functions of ζ in T cell development in vivo but that TCR/CD3 complexes associated with FcRγ rather than ζ are less well expressed on cells. Also, these results revealed a difference in the regulation of expression of the TCR/CD3 complex on CD4+ and CD8+ T cells.

Expression of the α–β antigen receptor on the T cell surface (TCR) and TCR signal transduction are effected by a number of polypeptides. These include the TCR-associated CD3 γ, δ, and ɛ chains, the ζ homodimer, and a number of intracellular proteins (1–9). The signals transduced by these molecules can lead to several different responses by the cell (10–14). Although the cytoplasmic tails of the TCR/CD3 γ, δ, ɛ, and ζ all include immunoreceptor tyrosine-based activation motifs [which can bind tyrosine kinases and participate in signal transduction (1–9)], it is not clear that signaling via all of these proteins has the same consequences for the T cell (6, 15, 16). In addition, the γ chain of the high affinity IgE receptor (FcRγ chain) and ζ chains are structurally homologous and can form disulfide-linked homo- and heterodimers and associate with other TCR chains (17–20). In attempts to study the functional differences between these molecules in vivo, some of us and other groups have generated knockout mice containing inactivated ζ chain genes [ζKO mice, (21–24)]. Thymocytes and T cells in these mice expressed very low levels of surface TCR, confirming the contribution of ζ to TCR expression on the cell surface. Also, the ζKO mice had very few mature thymocytes, suggesting that ζ is crucial to T cell maturation.

ζKO mice do not completely lack T cells bearing high levels of TCR. A novel population of intestinal T cells in both normal and ζKO mice expresses TCR in which the FcRγ chain substitutes for the ζ chain (21, 23). This population is characterized by expression of CD8 comprised only of CD8 α chains, rather than the α–β CD8 dimers expressed on most mature T cells. This population also is relatively nonresponsive to stimuli, such as anti-CD3 antibodies. The reasons for these differences are unknown. However, some T cells in animals carrying solid tumors also express FcRγ instead of ζ and are relatively nonresponsive to stimulation via their TCRs (25). Therefore, substitution of FcRγ for ζ may lead to the nonresponsive properties of the T cells in which this has occurred.

To test this idea and to examine from another perspective the role of ζ in TCR expression and thymocyte development, we produced mice transgenic for the FcRγ chain and lacking ζ (FcRγTG ζKO mice). The results showed that substitution of FcRγ for ζ allows T cell development and does not inevitably create nonresponsive T cells. Unexpectedly, however, mature CD4+ T cells in FcRγTG ζKO mice bore less TCR than CD8+ T cells did. The difference in effect between mature CD4+ and CD8+ T cells suggests that the structure of the TCR and its associated proteins and signal transduction cascades is not the same in these two cell types.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mice.

FcRγ cDNA was fused downstream to the promoter and enhancer elements of the mouse CD3 δ gene derived from a previously described DNA cassette (26). The transgenic mice of C57BL/6 background were then bred with ζKO mice (21) to obtain FcRγTG+ ζKO mice. The presence of the transgene and deficiency in ζ were confirmed in these mice by anti-ζ antibody (H-146; ref. 27) staining and by PCR of genomic DNA. Six- to 12-week-old animals were used for experiments. Except when otherwise noted, FcRγTG− ζ+/− (ζ+) and FcRγTG− ζKO (ζKO) animals served as controls. B10.BR and Balb/cnSn mice were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory. Mice deficient in β2-microglobulin and expressing H-2k were bred in the Animal Care Facility, National Jewish Center, from the F1 progeny of β2-microglobulin-deficient H-2b animals (Taconic Farms, Germantown, NY) and B10.BR mice.

Cell Purification.

Cell suspensions were prepared as described (28).

Quantitative Examination of FcRγ mRNA Levels.

Total RNA was prepared from thymocytes or T cells as described (29) and was converted into first strand cDNA using a kit (GIBCO). A comparative semiquantitative PCR was done to compare the amounts of FcRγ gene message in the various cell populations. The PCR conditions used were 95°C for 30 sec, 60°C for 50 sec, and 72°C for 60 sec, for a total of 35 cycles. A ubiquitous gene, GαS, was used as an internal control message for the cDNA synthesis and PCR (30). The 5′ primer for both the GαS and the FcRγ genes was conjugated with fluorescein. The intensity of the amplified DNA bands from 2-fold serial dilutions of cDNA templates was quantitated using a fluoroimager (Molecular Dynamics). The intensities of the FcRγ bands at cDNA dilutions of CD4 and CD8 T cells (which gave rise to comparable intensities of the reference GαS cDNA bands) were compared.

Western Blot Analysis.

Cells were lysed in 0.5% Triton X-100 (Pierce) lysis buffer (150 mM NaCl/1 mM EDTA/20 mM Tris/10.8 mM iodoacetamide/1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride/peptidase inhibitors). Proteins were separated by electrophoresis on 15% nonreducing SDS/polyacrylamide gels and transferred to poly(vinylidene difluoride) membranes (Immobilon; Millipore). Membranes were blocked by incubation in 5% nonfat milk or BSA buffer and then blotted with anti-FcRγ antiserum (18) or anti-CD3 ɛ antiserum (Dako). Proteins were detected using an enhanced chemiluminescent detection kit (Amersham).

Staining with Antibodies.

Staining of thymocytes and lymph node cells was done as described (28).

Mouse Immunization and Production of T Cell Hybridomas.

Mice were immunized in the base of the tail with chicken ovalbumin 323-339 or mouse Eα 52-68. Both of these peptides are known to bind to I-Ab, the class II major histocompatibility complex (MHC) protein expressed in the mice used for these experiments (31, 32). Seven days later, cells were harvested from the draining nodes of these animals and incubated for 4 days with the appropriate antigenic peptide and then 3 days with interleukin 2 before fusion with an α−–β− TCR variant of the thymoma BW5147. Hybrids were selected, grown, and tested for response to I-Ab or antigenic peptide plus I-Ab by standard techniques (33). Spleen cells from C57BL/10 mice were used as presenting cells.

In Vitro Responses and Cytotoxic T Cell Assays.

T cells were titrated for their proliferative response to peptide antigens or anti-TCR antibody bound to plastic or to allogeneic spleen cells by standard techniques (34). The Eα 52-68 or chicken ovalbumin peptide 323-339 was used as antigen at 10 μM. Antibodies used for stimulation were fixed to Immulon 4, 96-well, flat-bottomed plates (Dynatech) at a concentration of 10 μg/ml during an overnight incubation at 4°C or for 4 h at 37°C. Cells were cultured in these wells for 72 h at 37°C and incubated with 1 μCi (1 Ci = 37 GBq) of [3H]thymidine (Amersham) per well during the last 16–18 h of incubation. Cells were harvested on a Harvester 96 Mach III M (Tomtec, Orange, CT), and incorporation was determined on a Microbeta PLUS liquid scintillation counter (Wallac, Turku, Finland).

Primary mixed lymphocyte reactions were done using splenocytes from B10.BR (H-2k) and B10.BR mice lacking functional β2-microglobulin genes as class I positive and negative allogeneic stimulators, respectively. Splenocytes from C57BL/10 (H-2b) mice were used as syngeneic stimulators. Responder splenocytes (5 × 105/well) were incubated with irradiated stimulators (5 × 105/well) for 4 or 5 days. During the last 16–18 h of incubation, 1 μCi of [3H]thymidine was added and cells were harvested.

Allospecific cytotoxic effector T cells were generated by culturing responder splenocytes (5 × 106/ml) with irradiated splenocytes from Balb/c H-2d mice as allostimulators (2–5 × 106/ml). Exogenous interleukin 2 was added at 10 units/ml to the culture after the first 2 days of the 6-day culture. Tumor target cells were labeled with Na51Cr (100 μCi/106 cells in 200 μl medium) for 2 h at 37°C, washed, and incubated (5000 cells/well) with effector cells at various ratios in V-bottom plates. Effector cells were then incubated at 37°C with tumor target cells with or without the anti-CD8 antibody YTS-169.4.2 (1 μg/106 effectors; ref. 35) in a standard 4-h 51Cr release assay. The percentage of specific lysis was calculated as described (34).

RESULTS

The FcRγ Chain Allows Thymocyte Maturation.

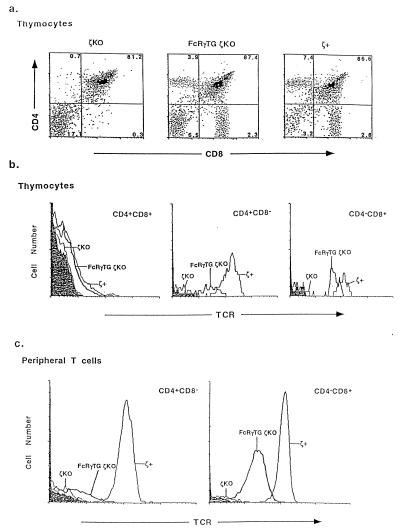

Expression of the FcRγ transgene in thymocytes and T cells of FcRγTG ζKO mice was demonstrated using PCR. Expression of the FcRγTG transcript could be detected in the thymuses and mature peripheral CD4+ or CD8+ T cells of FcRγTG ζKO mice but not in those of the same cell populations from nontransgenic ζ+ or ζKO mice (data not shown). Analysis of the thymuses showed, as described before, that the thymuses of ζKO mice contained very few cells. Expression of the FcRγ transgene restored the cellularity of thymuses in mice lacking ζ to relatively normal levels (Fig. 1a). The thymocytes from these animals were stained for CD4, CD8, and TCR expression. As shown in Fig. 1a, the thymuses from ζKO mice contained very low percentages of mature CD4+CD8− and CD4−CD8+ single-positive (SP) thymocytes, indicating, as previously shown, that thymocyte maturation was very inefficient in these animals (21–24). As suggested by its effects on thymus cellularity, however, expression of the FcRγTG restored the population of SP thymocytes. Hence, the FcRγ chain could substitute for ζ in allowing relatively normal development of mature thymocytes.

Figure 1.

The FcRγ transgene restores T cell development in ζKO mice. (a) The FcRγ replaces ζ in allowing normal development in thymus. Thymuses were removed from various types of mice. Their cellularities were as follows: ζKO, 30 ± 12 × 106; FcRγTG ζKO, 110 ± 21 × 106; and ζ+, 140 ± 18 × 106. Thymocytes were stained with fluorescein isothiocyanante–anti-CD8, phycoerythrin–anti-CD4, and biotin–anti-TCR plus cychrome–streptavidin. (b) Double-positive thymocytes from FcRγTG ζKO mice express nearly normal levels of TCR, but these levels are reduced on SP thymocytes, particularly the CD4+ SP thymocytes. (c) Mature peripheral T cells in FcRγTG+ ζKO mice express TCR at lower levels than those of thymocytes and mature T cells in ζ+ mice.

The FcRγ Partially Restores TCR Levels on Thymocytes and T Cells in ζKO Mice.

Previous experiments have suggested that ζ is important for thymocyte development not because it is involved in signal transduction during positive selection but rather because it contributes to the appearance of the TCR at high levels on the surface of immature thymocytes (36). This was shown by introduction of a ζ transgene lacking its cytoplasmic tail into ζKO animals. The tailless ζ transgene restored the levels of TCR on thymocytes from the undetectable amounts in ζKOs to higher amounts and restored nearly normal thymocyte maturation patterns to the ζKO animals. Therefore, the finding described above (that FcRγ could substitute for ζ in allowing thymocyte maturation) suggested that this polypeptide facilitated the appearance of TCR on the surfaces of thymocytes.

To test this idea, we measured the TCR levels per cell on various thymocyte and mature T cell populations in the different types of mice. The levels of TCR on the immature, double-positive thymocytes of FcRγTG ζKO animals were higher than on the same cells from ζKO mice but were lower than on those of ζ+ mice (Fig. 1b; Table 1). It is difficult to estimate exactly how much lower these levels were because the levels were estimated as the average of all double-positive thymocytes, even though some of these cells in both types of mice bore no TCR.

Table 1.

TCR levels are low on thymocytes and T cells in FcRγTG ζKO mice

| Cell type | Mean

channel staining with anti-Cβ in mice

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| ζKO | FcRγTG ζKO | ζ+ | |

| CD4+CD8+ thymocytes* | 4.0 ± 1.0† | 6.4 ± 1.6 | 13.7 ± 2.5 |

| CD4+ thymocytes | 4.6 ± 0.5 | 27.1 ± 5.1 | 215.6 ± 15.0 |

| CD8+ thymocytes | 4.4 ± 0.4 | 49.7 ± 9.4 | 152.8 ± 19.9 |

| CD4+ lymph node T cells | 4.7 ± 0.7 | 6.5 ± 1.3 | 133.6 ± 4.7 |

| CD8+ lymph node T cells | 5.6 ± 1.2 | 24.6 ± 3.2 | 124.2 ± 6.0 |

Gated on all CD4+CD8+ thymocytes even though some are TCR− because the TCR+ and TCR− populations could not be distinguished clearly (see Fig. 2b).

Data are given as the mean ± SE of five independent assays.

In normal mice, TCR levels per cell increase during thymocyte maturation and then remain approximately constant after the cells enter peripheral lymph nodes and spleen. Mature CD4+ thymocytes and T cells bear somewhat more TCRs per cell than mature CD8+ cells. In FcRγTG ζKO animals, the TCR levels per cell also increased during thymocyte maturation, except that, unlike the situation in ζ+ animals, CD8+ cells expressed higher TCR levels than CD4 cells. Although TCR levels per cell dropped when thymocytes became mature peripheral T cells in control mice, unexpectedly, in FcRγTG ζKO mice, TCR levels per cell fell even more markedly after the cells had left the thymus. This was particularly true for CD4+ cells. Thus, in these mice, the TCR levels on CD8+ lymph node cells were 50% of those on CD8+ thymocytes, but TCR levels on CD4+ T lymph node T cells were 25% of those on CD4+ thymocytes. In fact, the levels of TCR on peripheral CD4+ T cells in FcRγTG ζKO mice were only slightly higher than those of CD4+ cells in ζKO animals (Fig. 1 b and c; Table 1).

The upshot of these phenomena was 2-fold. First, TCR levels were higher on CD4+ cells than on CD8+ cells in ζ+ mice whereas they were higher on CD8+ cells than on CD4+ cells in FcRγTG ζKO mice. Second, the difference between TCR levels in FcRγTG ζKO mice and ζ+ mice became more marked as the cells matured. For example, CD8+ SP thymocytes from FcRγTG ζKO animals stained on average about one-third as intensely as their ζ+ counterparts, with some overlap in the staining of these cells from the two types of mice. For mature CD8+ lymph node T cells, on the other hand, FcRγTG ζKO cells stained only one-fifth as well as their ζ+ counterparts, and there was virtually no overlap between the two staining profiles (Fig. 1 b and c; Table 1).

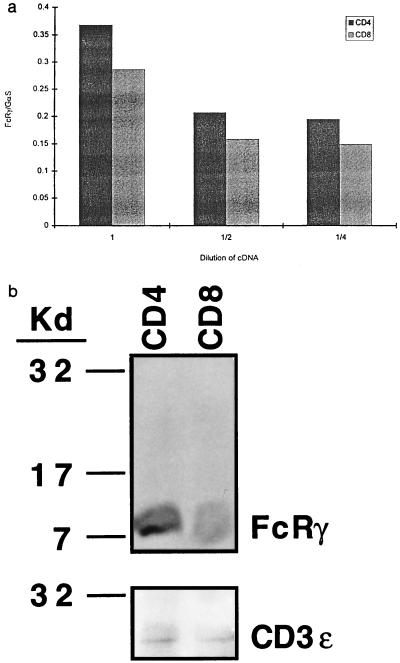

Comparative semiquantitative PCRs and Western blot analyses were done to find out whether the difference in TCR level between mature CD4+ and CD8+ T cells was due to low expression of the FcRγ transgene in these cells. After normalization for expression of GαS, a ubiquitous gene, the results of PCR showed that the FcRγ transgene was expressed well in mature T cells and, in fact, was expressed slightly better in mature CD4+ T cells than it was in mature CD8+ cells (Fig. 2a). Western blot analyses were done to check that mRNA levels reflected protein expression in the cells. These analyses revealed that whole cell lysates from CD4 and CD8 T cells contained comparable amounts of FcRγ protein per cell as well as comparable amounts of a control protein, CD3 ɛ (Fig. 2b).

Figure 2.

(a) Mature CD4+ T cells expressed more transcripts of the transgene than mature CD8+ T cells. Comparison of the amount of PCR-amplified cDNA of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells from FcRγTG mice was made at three different cDNA dilutions, at which the amplified DNA band intensities of a reference cDNA, GαS, were comparable. The FcRγ PCR product is the lower band. The y axis represents arbitrary units of the ratio of DNA band intensity of FcRγ and GαS. (b) Mature CD4+ T cells expressed the same, if not more, FcRγ protein as CD8+ T cells. Whole cell lysates of 5 × 106 CD4+ or CD8+ cells were run on reducing SDS/PAGE, blotted, and probed with anti-FcRγ antibody as described. After detection, the membranes were stripped and reblotted with anti-CD3 ɛ antisera.

Low TCR expression on mature T cells was not due simply to expression of the FcRγ transgene because cells from ζ+ mice that were also positive for the transgene did not have unexpectedly low levels of TCR on their surfaces. On the contrary, the levels of TCR on T cells from ζ+ (actually ζ+/−, see above) mice, usually about half of those on ζ+/+ cells, were almost doubled by coexpression of FcRγ (data not shown).

Staining experiments also revealed that the CD8 protein on the mature T cells in FcRγTG ζKO mice was made up of CD8 α–β heterodimers (data not shown). Therefore, CD8 on these cells did not have the CD8 α–α composition found on other T cells that have been found to express FcRγ instead of ζ (data not shown; ref. 37).

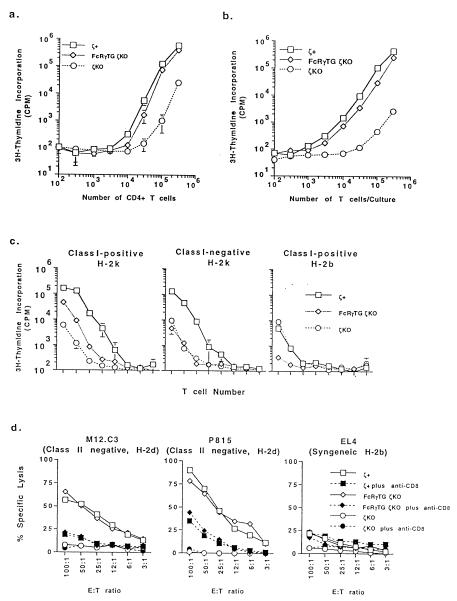

The Mature T Cells in FcRγ ζKO Mice Are Functional.

CD4+ T cells isolated from the FcRγ ζKO mice proliferated as vigorously as cells from ζ+ animals in response to stimulation by anti-TCR antibodies (Fig. 3a). The CD4+ T cells also were tested in experiments in which spleen and lymph node T cells from the mice were challenged with allogeneic spleen cells bearing either allogeneic class I and class II MHC proteins or only allogeneic class II. Although the T cells from FcRγTG ζKO mice responded well to stimulation with cells bearing allogeneic class I and class II proteins, they did not respond significantly to spleen cells bearing only allogeneic class II (Fig. 3c). These results suggested that the CD8+ T cells of these mice were fully functional but that the CD4+ T cells might not be. To test the latter idea in greater detail, FcRγTG ζKO, ζKO, and ζ+ mice were primed with peptide antigens mouse Eα peptide 52-68 or chicken ovalbumin peptide 323-339. Both of these peptides are known to bind to I-Ab, the class II MHC protein expressed in the mice used for these experiments (31, 32). After priming, T cells from FcRγTG ζKO and ζ+ mice responded well to the antigen in vitro (Fig. 3b), and functional CD4+ T cell hybridomas could be produced with ease from these cells (see below). T cells from ζKO mice did not respond well and did not give rise to antigen-specific T cell hybridomas after fusion (see below).

Figure 3.

T cells from FcRγ ζKO mice are functional. (a) CD4+ T cells from FcRγ ζKO mice respond to anti-TCR antibody. Purified CD4+ T cells from FcRγ ζKO, ζKO, and ζ+ mice were titrated for response to anti-TCR Cβ antibody bound to plastic as described. In addition, T cells from FcRγ ζKO and ζ+ mice showed similar proliferative responses to various amounts of anti-TCR antibody after antibody titration whereas T cells from ζKO did not respond well to the antibody at the tested concentrations (data not shown). (b) T cells from FcRγ ζKO mice respond well to an antigenic peptide. Mice were primed with the mouse Eα peptide 52-68, and T cells from these animals were titrated for their activity to respond to in vitro challenge with Eα 52-68 as described. (c) CD8+ but not CD4+ T cells from FcRγ ζKO mice respond in primary mixed lymphocyte reactions. Spleen and lymph node cells from FcRγ ζKO, ζKO, and ζ+ mice were titrated for their ability to respond to stimulator cells bearing the allogeneic class I and class II proteins of H-2k (Left), allogeneic class II of H-2k without class I (Center), and syngeneic class I and class II of H-2b (Right). Cultures were set up as described. The target and responding cells in the various reactions are indicated. (d) CD8+ T cells from FcRγ ζKO mice can become cytotoxic effector cells. H-2d-specific cytotoxic T cells were generated from FcRγ ζKO, ζKO, or ζ+ mice by culture with spleen cells from H-2d mice as described. Cytotoxic T cells generated in these cultures were assayed by killing H-2d-bearing M12.C3 and P815 target cells. Stimulators and responding cells are indicated.

The idea that CD8+ T cells from FcRγTG ζKO animals could respond was confirmed by the generation of cytotoxic T cells. Spleen and lymph node T cells from the various types of mice were stimulated in vitro with allogeneic spleen cells from H-2d mice. After the mixed lymphocyte reactions, the T cells were tested for their ability to kill M12.C3 and P815 cells, cells that bear class I proteins of the H-2d type. As shown in Fig. 3d, T cells from the FcRγTG ζKO mice, after stimulation, could kill class I MHC+ target cells specifically in a CD8-dependent fashion.

T Cells in FcRγTG ζKO Mice Are Tolerant to Self.

Several hypotheses can be suggested to account for the low levels of TCR on mature T cells in FcRγTG ζKO mice. Some of these invoke the mechanisms of tolerance. For example, if substitution of FcRγ for ζ was to interfere somehow with deletion of potentially autoreactive T cells in the thymus, low levels of TCR on their descendants, once mature, might be induced by constant exposure to self antigen in the periphery. We set out to test the notion directly in two ways.

First, we examined the use of Vβ by mature T cells in the FcRγTG ζKO mice. Unfortunately, this analysis could only be done for CD8+ T cells because their very low levels of TCR precluded such an examination of CD4+ mature T cells. The results showed that the percentages of CD8+ T cells bearing various Vβs were not deleted by the C57- and 129-derived mouse mammary tumor virus 8, 9, and 17 superantigens expressed in these mice nor by virus superantigens 3 and 13, which might have been inherited from the 129 parent (data not shown). All of the animals in these experiments expressed I-Ab, which participates in only weak reactions between mouse mammary tumor virus superantigens and their targets, so the assay was not very sensitive to low levels of rescue from deletion by substitution of ζ by FcRγ.

To test the idea that thymus tolerance might be defective in the experimental mice, the animals were primed with antigens. T cell hybridomas were produced from the antigen-specific T cell blasts and tested for their ability to respond to self class II MHC, I-Ab, in the absence or presence of antigenic peptides. T cell hybridomas produced from FcRγTG ζKO mice expressed TCR and CD4 at the same high levels as those produced from ζ+ or wild-type animals (data not shown). Thus, the lower TCR expression on the CD4+ T cells in FcRγTG ζKO mice could be restored by fusion to BW5147, which expresses ζ. Although some of the T cell hybridomas produced from FcRγTG ζKO did respond to syngeneic spleen cells in the absence of antigenic peptides, the frequency of these autoreactive hybridomas was not particularly higher among the hybrids produced from FcRγTG ζKO T cells than it was among the hybrids produced from ζ+ T cells (Table 2). On the other hand, although only five T cell hybridomas were obtained from ζKO mice, one of the five T cell hybridomas was autoreactive. Therefore, this experiment did not support the idea that the T cells in FcRγTG ζKO mice bear potentially autoreactive TCRs.

Table 2.

Frequency of T cell hybridomas reactive to self MHC with or without exogenous antigen

| Source of T hybridomas | Responds to C57BL/10, % (n)

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Without OVA 323-339 | With OVA 323-339* | |

| ζKO | 20 (1/5) | 0 (0/5) |

| FcRγTG ζKO | 7 (10/144) | 75 (108/144) |

| ζ+ | 4 (4/96) | 80 (77/96) |

OVA, ovalbumin.

Similar percentages of autoreactive and antigen-reactive hybridomas were obtained from mice primed with Eα 52-68 peptide.

DISCUSSION

As we have shown previously, thymus cellularity is greatly reduced, and TCR expression on thymocyte surfaces is at almost undetectable levels in mice lacking ζ (21). The experiments in this study showed that FcRγ can substitute, to some extent, for ζ in allowing expression of surface TCR in vivo, a result that is consistent with previous in vitro studies (5, 18, 20, 38). As far as this function is concerned, the FcRγ chain operates quite effectively in immature thymocytes but less well in mature thymocytes and even less effectively in mature T cells, particularly those bearing CD4. The reasons for this interesting phenomenon remain obscure. It is unlikely that FcRγ availability caused the lowered TCR expression. The FcRγ transgene is well expressed in both mature CD4 and CD8 T cells and easily can be detected using PCR and Western blot analysis. The phenomenon does not appear to be driven by an immune response, for example, by reactivity of the mature T cells with their hosts. It may not be due to interference in TCR/CD3 assembly by FcRγ because TCR levels actually increased on T cells from ζ+/− mice that also expressed the FcRγ transgene.

The phenomenon may be due to some altered biochemical events associated with FcRγ expression in the absence of ζ in mature T cells. The fact that the ratio of TCR expression on cells in FcRγTG ζKO mice and ζ+ animals decreased as the cells matured might provide a clue to the alteration. For example, the phenomenon might be related to differences in the half-life of TCRs on the surfaces of different types of cells. FcRγ-bound TCRs might have a shorter half-life than TCRs engaged with ζ, and double-positive thymocytes, with their short half-lives and relatively active TCR synthetic machinery, may be able to compensate for this more easily than the longer-lived, mature thymocytes and peripheral T cells.

Alternatively, the phenomenon may be related to changes in the intracellular signaling pathways that are unique to the FcRγ chain. It is possible that the fall in TCR expression observed during thymocyte maturation in FcRγTG ζKO animals may be due to changes in the tyrosine kinases associated with the TCR as the cells develop. If so, the fact that the consequences are more profound for CD4+ T cells than they are for CD8+ cells may reflect differences in TCR-associated tyrosine kinases between the two cell types, an idea that has already been suggested in ZAP-70-deficient individuals, although admittedly only in humans and not in mice (39–42). In addition, p56lck, a Src family kinase, may play a role in the differential expression of the TCR. For example, it has been shown that p56lck, which associates with a larger proportion of CD4 than with CD8, may regulate TCR expression levels (43–45). It is possible that the preferential association of p56lck with CD4 may result in CD4+ thymocytes and T cells expressing lowered levels of TCRs containing FcRγ but not ζ. Our future experiments will test these hypotheses.

This study was based on previous findings that intraepithelial T lymphocytes from the gut of ζKO and normal mice or T cells from tumor-bearing animals in which ζ has been replaced by FcRγ lack reactivity to stimuli via their TCRs (21, 25). Of interest, the experiments shown above demonstrate that the nonreactivity of the novel population of T cells from normal mouse intestine or from tumor-bearing animals is not due solely to this substitution. Clearly, cells with such substitution in their TCR can respond vigorously to many stimuli. The lack of reactivity of the FcRγ+ intraepithelial lymphocytes or cells from tumor-bearing animals must therefore be caused by some other phenomenon.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. J.-P. Kinet for providing cDNA and antisera for FcRγ and Dr. E. Lacy for the CD3 δ promoter/enhancer DNA cassette. We also thank Drs. J. Cambier and C. Hall for their helpful suggestions and Drs. T. Potter and S. Dow for their help with cytotoxic T cell assays. We also greatly appreciate help from D. Becker, who made the transgenic mice, and H. Gognat, who helped to type them. This work was supported by U.S. Public Health Service Grants AI-17134, AI-18785, and AI-22295.

Footnotes

Abbreviations: TCR, T cell receptor; FcRγ chain, γ chain of the high affinity IgE receptor; ζKO mice, knockout mice containing inactivated ζ chain genes; FcRγTG ζKO mice, mice transgenic for the FcRγ chain and lacking ζ; SP, single-positive; MHC, major histocompatibility complex.

References

- 1.Reth M. Nature (London) 1989;338:383–384. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ashwell J D, Klausner R D. Annu Rev Immunol. 1990;8:139–167. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.08.040190.001035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Letourneur F, Klausner R D. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:8905–8909. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.20.8905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Irving B A, Weiss A. Cell. 1991;64:891–901. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90314-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Romeo C, Seed B. Cell. 1991;64:1037–1046. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90327-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wegener A-M K, Letourneur F, Hoeveler A, Brocker T, Luton F, Malissen B. Cell. 1992;68:83–95. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90208-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Samelson L E, Klausner R D. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:24913–24916. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chan A C, Desai D M, Weiss A. Annu Rev Immunol. 1994;12:555–592. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.12.040194.003011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cambier J C. Immunol Today. 1995;16:110. doi: 10.1016/0167-5699(95)80105-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Robey R, Fowlkes B J. Annu Rev Immunol. 1994;12:675–705. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.12.040194.003331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ashton-Rickardt P, Tonegawa S. Immunol Today. 1994;15:362–366. doi: 10.1016/0167-5699(94)90174-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Janeway C A J. Immunity. 1994;1:3–6. doi: 10.1016/1074-7613(94)90003-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jameson S C, Hogquist K A, Bevan M J. Annu Rev Immunol. 1995;13:93–126. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.13.040195.000521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kisielow P, von Boehmer H. Adv Immunol. 1995;58:87–209. doi: 10.1016/s0065-2776(08)60620-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Finkel T H, Marrack P, Kappler J W, Kubo R T, Cambier J C. J Immunol. 1989;142:3006–3012. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Letourneur F, Klausner R D. Science. 1992;255:79–82. doi: 10.1126/science.1532456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ra C, Jouvin M H E, Blank U, Kinet J. Nature (London) 1989;341:752–754. doi: 10.1038/341752a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Orloff D G, Ra C, Frank S J, Klausner R D, Kinet J-P. Nature (London) 1990;347:189–191. doi: 10.1038/347189a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ravetch J V, Kinet J-P. Annu Rev Immunol. 1991;9:457–492. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.09.040191.002325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rodewald H R, Arulanandam A R N, Koyasu S, Reinherz E L. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:15974–15978. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liu C-P, Ueda R, She J, Sancho J, Wang B, Weddell G, Loring J, Kurahara C, Dudley E C, Hayday A, Terhorst C, Huang M. EMBO J. 1993;12:4863–4875. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1993.tb06176.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Love P E, Shores E W, Johnson M D, Tremblay M L, Lee E J, Grinberg A, Huang S P, Singer A, Westphal H. Science. 1993;261:918–921. doi: 10.1126/science.7688481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Malissen M, Gillet A, Rocha B, Trucy J, Vivier E, Boyer C, Koentgen F, Brun N, Mazza G, Spanopoulou E, Guy-Grand D, Malissen B. EMBO J. 1993;12:4347–4355. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1993.tb06119.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ohno H, Aoe T, Taki S, Kitamura D, Ishida Y, Rajewsky K, Saito T. EMBO J. 1993;12:4357–4366. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1993.tb06120.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mizoguchi H, O’Shea J J, Longo D L, Loeffler C M, McVicar D W, Ochoa A C. Science. 1992;258:1795–1798. doi: 10.1126/science.1465616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lee N A, Loh D Y, Lacy E. J Exp Med. 1992;175:1013–1026. doi: 10.1084/jem.175.4.1013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rozdzial M M, Kubo R T, Turner S L, Finkel T H. J Immunol. 1994;153:1563–1580. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Liu C-P, Kappler J W, Marrack P. J Exp Med. 1996;184:1619–1630. doi: 10.1084/jem.184.5.1619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chomczynski P, Sacchi N. Anal Biochem. 1987;162:156–159. doi: 10.1006/abio.1987.9999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jones D T, Reed R R. J Biol Chem. 1987;262:14241–14249. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shimonkevitz R, Colon S, Kappler J W, Marrack P, Grey H M. J Immunol. 1984;133:2067–2074. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rudensky A, Preston-Hurlburt P, Hong S C, Barlow A, Janeway C A., Jr Nature (London) 1991;353:622–627. doi: 10.1038/353622a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kappler J W, Skidmore B, White J, Marrack P. J Exp Med. 1981;153:1198–1214. doi: 10.1084/jem.153.5.1198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Coligan J, Kruisbeek A, Margulies D, Shevach E, Strober W, editors. Current Protocols in Immunology. New York: Wiley; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cobbold S P, Jayasuriya A, Nash A, Prospero T D, Waldmann H. Nature (London) 1984;312:548–551. doi: 10.1038/312548a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shores E W, Huang K, Tran T, Lee E, Grinberg A, Love P E. Science. 1994;266:1047–1050. doi: 10.1126/science.7526464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Guy-Grand D, Rocha B, Mintz P, Malassis-Seris M, Selz F, Malissen B, Vassalli P. J Exp Med. 1994;180:673–679. doi: 10.1084/jem.180.2.673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Paolini R, Renard V, Vivier E, Ochiai K, Jouvin M H, Malissen B, Kinet J-P. J Exp Med. 1995;181:247–255. doi: 10.1084/jem.181.1.247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Arpaia E, Shahar M, Dadi H, Cohen A, Roifman C M. Cell. 1994;76:947–958. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90368-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Elder M E, Lin D, Clever J, Chan A C, Hope T J, Weiss A, Parslow T G. Science. 1994;264:1596–1599. doi: 10.1126/science.8202712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chan A C, Kadlecek T A, Elder M E, Filipovich A H, Kuo W L, Iwashima M, Parslow T G, Weiss A. Science. 1994;264:1599–1601. doi: 10.1126/science.8202713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Negishi I, Motoyama N, Nakayama K, Nakayama K, Senju S, Hatakeyama S, Zhang Q, Chan A C, Loh D Y. Nature (London) 1995;376:435–438. doi: 10.1038/376435a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wiest D L, Yuan L, Jefferson J, Benveniste P, Tsokos M, Klausner R D, Glimcher L H, Samelson L E, Singer A. J Exp Med. 1993;178:1701–1712. doi: 10.1084/jem.178.5.1701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ravichandran K S, Burakoff S J. J Exp Med. 1994;179:727–732. doi: 10.1084/jem.179.2.727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ericsson P O, Teh H S. Int Immunol. 1995;7:617–624. doi: 10.1093/intimm/7.4.617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]