Abstract

This paper tests the hypothesis that cytosine DNA methyltransferase (DNA MeTase) is a candidate target for anticancer therapy. Several observations have suggested recently that hyperactivation of DNA MeTase plays a critical role in initiation and progression of cancer and that its up-regulation is a component of the Ras oncogenic signaling pathway. We show that a phosphorothioate-modified, antisense oligodeoxynucleotide directed against the DNA MeTase mRNA reduces the level of DNA MeTase mRNA, inhibits DNA MeTase activity, and inhibits anchorage independent growth of Y1 adrenocortical carcinoma cells ex vivo in a dose-dependent manner. Injection of DNA MeTase antisense oligodeoxynucleotides i.p. inhibits the growth of Y1 tumors in syngeneic LAF1 mice, reduces the level of DNA MeTase, and induces demethylation of the adrenocortical-specific gene C21 and its expression in tumors in vivo. These results support the hypothesis that an increase in DNA MeTase activity is critical for tumorigenesis and is reversible by pharmacological inhibition of DNA MeTase.

Modification of DNA by methylation is now recognized as an important mechanism of epigenetic regulation of genomic functions (1–3). Methylation of DNA is a postreplication event catalyzed by the DNA methyltransferase (DNA MeTase) enzyme using S-adenosyl methionine as a methyl donor (4). Approximately 80% of cytosines located in the CpG dinucleotide sequence are methylated in the genome of most vertebrate cells, but the distribution of methylated sites is cell- and tissue-specific (5). Patterns of methylation are generated during development by enzymatic de novo methylation and demethylation processes (1–7) and are maintained in somatic cells.

A number of observations have suggested that the pattern of DNA methylation is disrupted in cancer cells (8, 9). Both hypomethylation (9) and hypermethylation (10–12) of different CpG sites in cancer cells and tissues relative to the cognate normal tissue have been documented. Some of the sites that are hypermethylated in tumors are located in tumor–suppressor loci such as p16 (13), retinoblastoma (14), von Hippel–Lindau (15), and Wilms tumor (16), and, recently, a new candidate tumor–suppressor gene was cloned by molecular analysis of the hypermethylated region in chromosome 17p13.3 (17). One possible explanation that has been proposed to explain the changes in DNA methylation observed in cancer cells is that they are the end result of a change in the enzymatic machinery controlling DNA methylation in the cell (7, 12, 18–20). In accordance with this hypothesis, cancer cell lines (21) and human tumors (22) have been shown to express elevated levels of DNA MeTase. Recently, Belinsky et al. (23) showed that increased DNA MeTase activity is an early event in carcinogen-initiated lung cancer in the mouse. Forced expression of DNA MeTase cDNA in murine NIH 3T3 cells leads to genomic hypermethylation and neoplastic transformation (24), and expression of an antisense mRNA to the DNA MeTase leads to loss of tumorigenicity of the adrenocortical carcinoma cell line Y1 (25).

Many stimuli may account for increased DNA MeTase activity in tumors. One possible molecular mechanism explanation of this elevation of DNA MeTase in cancer cells is that the expression of the DNA MeTase gene is regulated by oncogenic signaling pathways such as the Ras–Jun signaling pathway (18, 19). Modulation of this pathway can alter DNA MeTase expression and DNA methylation (26–28). Similarly, ectopic expression of Ha–ras leads to induction of demethylation activity in P19 cells (29), which can explain (18) the observed hypomethylation of some CpG sites in cancer cells (8, 9).

If hyperactivity of DNA MeTase is a critical, downstream component of oncogenic programs (25–28), it should be an excellent target for anticancer therapy (19). To test this hypothesis in an animal model, specific inhibitors of DNA MeTase are required. The only DNA MeTase inhibitor that has been available to date is the nucleoside analog 5-azadeoxycytidine (30). Although 5-azadeoxycytidine is an effective inhibitor of DNA methylation (30), it has many side effects that might compromise the interpretation of the experimental data and limit its clinical utility (19, 31, 32). The advent of antisense oligodeoxynucleotides as specific inhibitors of protein expression in whole animal systems offers new opportunities in approaching this hypothesis (33).

Y1 cells offer a model to test our hypothesis. First, this line [which was isolated from a naturally occurring adrenocortical tumor in an LAF1 mouse (34)] bears a 30- to 60-fold amplification of the cellular proto oncogene c-Ki-ras (35). Second, the molecular link between hyperactivation of Ras, DNA MeTase hyperactivity, and DNA methylation and the state of cellular transformation has been recently demonstrated (25, 28). Third, identification of effective antisense oligodeoxynucleotide inhibitors requires screening of a number of potential candidates. This can only be done effectively ex vivo. Y1 cells can be grown and tested for tumorigenic characteristics ex vivo as well as implanted in syngeneic LAF1 mice (25) in vivo, thus enabling the study of the effects of inhibition of DNA methylation in a whole animal system.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell Culture, ex Vivo Oligodeoxynucleotide Treatment, and Tumorigenicity Assays.

Y1 cells were maintained as monolayers in F-10 medium, which was supplemented with 7.25% heat-inactivated horse serum and 2.5% heat-inactivated fetal calf serum (Immunocorp, Montreal). The sequences of the oligodeoxynucleotides used in this study were as follows: antisense (HYB101584), 5′-TCT ATT TGA GTC TGC CAT TT-3′ corresponding to bases −2 to +18 in the murine DNA MeTase mRNA [relative to the putative translation initiation site (9)]; the scrambled sequence corresponding to the antisense sequence (HYB102277), 5′-TGT GAT TCT CCT TAT TCG AT-3′; and the reverse sequence (HYB101585), 5′-TTT ACC GTC TGA GTT TAT CT-3′. Phosphorothioate oligodeoxynucleotides were synthesized using phosphoramadite chemistry on a Biosearch model 8700 automated synthesizer and were purified by HPLC using a phenyl Sepharose column followed by DEAE 5PW anion exchange chromatography. The purity of all oligonucleotides was greater than 98% as determined by ion exchange chromatography. These experiments were performed in the absence of any lipid carrier to avoid nonspecific effects of the carrier in long term treatments and to recapitulate the situation in vivo, in which no carrier was used. This experimental paradigm required using oligodeoxynucleotides at the micromolar concentration range, which is higher than the concentrations required when lipid carriers are used.

DNA and RNA Analyses.

Genomic DNA was prepared from pelleted nuclei, and total cellular RNA was prepared from cytosolic fractions according to standard protocols (36–38).

Western Blot Analysis of DNA MeTase.

Rabbit polyclonal antibodies were raised (Pocono Rabbit Farm, Canadensis, PA) against a peptide sequence consisting of amino acids 1107–1125 of the mouse DNA MeTase (1101–1119 of the human DNA MeTase). The specificity of the polyclonal serum was tested by competition with the antigen peptide. Nuclear extracts (50 μg) were resolved on a 5% SDS/PAGE, transferred onto poly(vinylidene difluoride) membrane (Amersham), and subjected to immunodetection for the DNA MeTase according to standard protocols using a 1:2000 dilution of primary antibody and an enhanced chemiluminescence detection kit (Amersham) (40).

Assay of DNA MeTase Activity.

DNA MeTase activity (3 μg) was assayed by incubating 3 μg of nuclear extract with a synthetic, hemimethylated, double-stranded oligodeoxynucleotide (37) substrate and S-[methyl-3H]-S-adenosyl-l-methionine (78.9 Ci/mmol; Amersham) as a methyl donor for 3 h at 37°C as described (36).

Assay of C21 mRNA by Reverse Transcriptase–PCR.

The expression of the C21 gene was determined using our described primers and amplification conditions (41).

RESULTS

Antisense Oligodeoxynucleotides to the Translation Initiation Region of the Murine DNA MeTase Inhibit DNA MeTase mRNA, DNA MeTase Activity, and Tumorigenesis ex Vivo.

We have shown that expression of a 600-bp fragment bearing sequences encoding the 5′ domain of the DNA MeTase mRNA in the antisense orientation can inhibit DNA methylation and induce both cellular differentiation of 10T½ cells (43) and reversal of transformation of Y1 cells (25). Antisense expression vectors could not be used easily to study the function and therapeutic potential of inhibiting DNA MeTase in vivo. We therefore tested the possibility that shorter antisense oligodeoxynucleotides directed against the same region of the mRNA could recapitulate these effects. An antisense oligodeoxynucleotide [+18 to −2 (sequence as in Materials and Methods) when the translation initiation site is indicated, as in Bestor et al. (44)] was found to be active in a preliminary screen, and we further determined its mechanism of action.

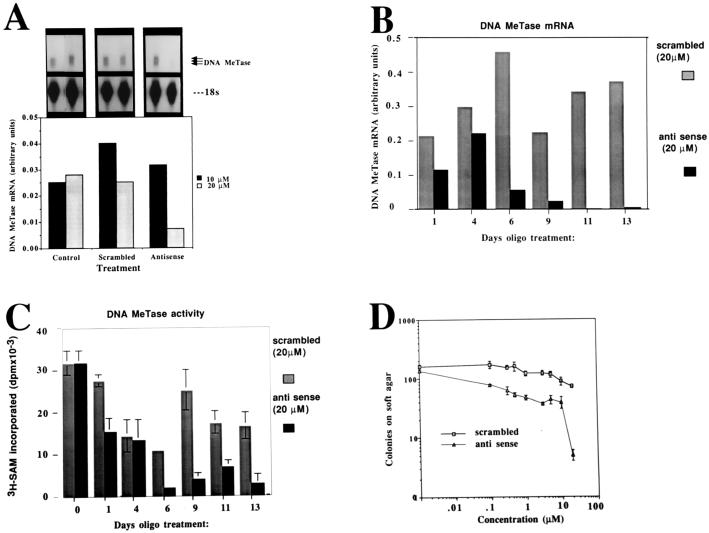

One of the possible mechanisms of action of antisense oligodeoxynucleotides is targeting RNase H activity to the RNA–DNA duplex, resulting in degradation of the mRNA (45). We first determined the dose–response relationship of DNA MeTase mRNA abundance and DNA MeTase antisense oligodeoxynucleotide concentration at one time point. Y1 cells (106 cells) were treated with different concentrations (0, 10, and 20 μM) of antisense oligodeoxynucleotides and scrambled controls for 48 h. Cellular RNA was subjected to an RNase protection assay as described in Materials and Methods. The results presented in Fig. 1A demonstrate a sharp decrease in abundance of DNA MeTase mRNA after incubation of the cells with 20 μM of the DNA MeTase antisense oligodeoxynucleotides, which was not observed after treatment with scrambled oligodeoxynucleotides. We then defined the time dependence of reduction in DNA MeTase activity at the inhibitory concentration of the antisense oligodeoxynucleotide (20 μM). The results presented in Fig. 1 B (RNA) and C (MeTase activity) show that both DNA MeTase activity and mRNA are reduced by 10- to 100-fold after 6 days of treatment. Some fluctuations are observed in the levels of DNA MeTase in Y1 cells treated with control oligodeoxynucleotides (2-fold) as well as antisense oligodeoxynucleotides (such as the relatively high levels of DNA MeTase at 4 days). These oscillations in DNA MeTase mRNA expression might reflect changes in the cell cycle kinetics of the cells at different time points because DNA MeTase levels are regulated with the cell cycle (35, 37). Alternatively, they might result from nonspecific effects of oligodeoxynucleotides on different cellular parameters or reflect some inaccuracies in our measurements. However, an overall reduction in DNA MeTase activity was established after 6 to 9 days of treatment with the antisense oligodeoxynucleotides.

Figure 1.

DNA MeTase antisense oligodeoxynucleotides inhibit DNA MeTase mRNA, DNA MeTase activity, and anchorage independent growth ex vivo. (A) RNase protection analysis of DNA MeTase mRNA in Y1 cells treated with control scrambled and antisense oligodeoxynucleotides. Y1 cells were cultured in the presence of different concentrations of scrambled and antisense oligodeoxynucleotides (sequence shown in Materials and Methods) as indicated for 48 h. RNA (3 μg) extracted from the cells was subjected to an RNase protection assay as described (26) using a 700-bp riboprobe [probe A in Rouleau et al. (26)] encoding the DNA MeTase genomic sequence from −0.39 to +318. The major bands representing the two major initiation sites are indicated (92-, 90-bp, protected fragments) as well as the first exon, which gives a 99-bp, protected fragment. (B) Time course of inhibition of DNA MeTase mRNA by antisense oligodeoxynucleotides. Y1 cells were incubated in the presence of 20 μM of either antisense or scrambled oligodeoxynucleotides, and the medium was replaced with oligodeoxynucleotide-containing medium every 24 h. Cells were harvested at the indicated time points, and RNA and nuclear extracts were prepared as described. RNA was subjected to RNase protection assay as described in A. An autoradiogram similar to the one presented in A was scanned, and the amount of DNA MeTase mRNA at each point was normalized to the signal obtained for 18s ribosomal RNA. (C) Nuclear extracts prepared from oligodeoxynucleotide-treated Y1 cells described in B were assayed for DNA MeTase activity as described. The results represent an average of triplicate determination ± SD. (D) Y1 cells were treated with scrambled and antisense oligodeoxynucleotides as described in B and seeded onto soft agar for determination of anchorage-independent growth as described. The results represent an average of triplicate determinations ± SD.

Can DNA MeTase antisense oligodeoxynucleotides induce a dose-dependent inhibition of tumorigenicity ex vivo as measured by anchorage-independent growth on soft agar? Y1 cells were treated with a range of concentrations of antisense and scrambled oligodeoxynucleotides (0–20 μM) for 13 days. The cells were harvested and plated onto soft agar as described (39). The results presented in Fig. 1D demonstrate a dose-dependent inhibition of colony formation on soft agar in antisense-treated cells vs. the scrambled control. The drop in the number of colonies formed on soft agar between 10 and 20 μM corresponds to the precipitous drop in DNA MeTase mRNA at this concentration of antisense oligodeoxynucleotide (Fig. 1A).

Inhibition of anchorage-independent growth of antisense-treated cells was observed even though the soft agar medium was not supplemented with antisense oligodeoxynucleotides, suggesting that the changes in the level of tumorigenicity of antisense-treated cells were irreversible. This is consistent with the hypothesis that, once DNA MeTase is inhibited, the cells are reprogrammed to a less transformed state (18, 25). The experiments described above demonstrated that antisense oligodeoxynucleotides could inhibit DNA MeTase activity ex vivo and that this inhibition corresponded to a dose-dependent inhibition of tumorigenicity.

Inhibition of Tumor Growth and DNA MeTase in Vivo by a DNA MeTase Antisense Oligodeoxynucleotide.

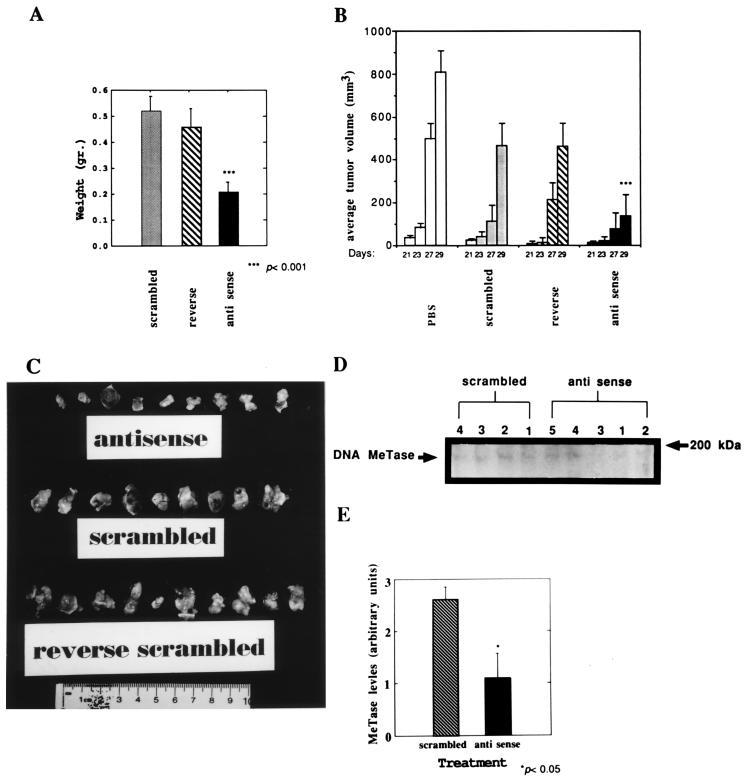

To test the hypothesis that inhibition of DNA MeTase in vivo can result in inhibition of tumor growth and to determine the general toxic effects of DNA MeTase antisense treatment, Y1 cells (1 × 106) were implanted in the flank of the syngeneic mouse strain LAF1 and were treated by i.p. injections every 48 h with PBS, antisense oligodeoxynucleotide, or two control oligodeoxynucleotides: a scrambled version of the antisense oligodeoxynucleotide and a reverse sequence (see Materials and Methods for sequence). Preliminary experiments with a small number of animals per group (n = 3) established a dose-dependent relationship between oligodeoxynucleotide concentrations and tumor growth. No effects were observed at 0.5 mg/kg whereas inhibition of tumor appearance and growth was observed in the 1- to 5-mg/kg range. At 20 mg/kg, nonspecific effects were observed with the scrambled oligodeoxynucleotides in two out of three experiments whereas a statistically significant reduction in tumor growth with antisense oligodeoxynucleotides vs. controls was observed in one experiment (data not shown). Forty LAF1 mice were implanted with Y1 cells, randomized, and divided into color-coded groups of 10 mice each and were treated and evaluated as follows in a double-blind fashion. Three days postimplantation, the mice were injected i.p. with 100 μl of PBS or PBS containing 5 mg/kg of either antisense, scrambled, or reverse oligodeoxynucleotides. Injections were repeated every 48 h, and tumor diameter measurements were taken at each time point. Thirty days postinjection, the animals were killed, and tumors were excised and weighed. The results described in Fig. 2 show that tumor growth was inhibited by injection of DNA MeTase antisense oligodeoxynucleotides relative to control oligodeoxynucleotides as determined by the rate of increase in the average tumor volume (Fig. 2B) as well as by the final weight and size of the tumors (Fig. 2 A and C). The difference in the average tumor volume between the antisense-treated group and either of the different control groups (PBS, scrambled, and reverse) at 29 days was highly statistically significant, as determined by a Student’s t test (P < 0.005) whereas the difference between the different control oligodeoxynucleotide-treated groups and the PBS-treated group was not statistically significant. Similarly, the difference in average final tumor weight at 30 days between the antisense- and control oligodeoxynucleotide-treated groups was highly statistically significant (P < 0.001). One of the antisense-treated animals did not develop tumors whereas all of the members of the control groups developed tumors (one mouse of the reverse group died with a heavy tumor load before termination of the experiment).

Figure 2.

DNA MeTase antisense oligodeoxynucleotide inhibits tumor growth in vivo. (A) Average weight of tumors isolated from LAF1 mice bearing Y1 tumors that were injected with antisense, scrambled, or reverse oligodeoxynucleotide (5 mg/kg) every 48 h for 29 days. The results are presented as an average ± SEM. The statistical significance of the difference between the scrambled or reverse groups and the antisense group was determined by a Student’s t test to be P < 0.001. There was no statistically significant difference between the two control groups (P > 0.5). (B) Average volume of tumors determined as described at the indicated time points postimplantation [determined as described in Plumb et al. (42)]. (C) Photograph of the tumors removed from the antisense, reverse, and scrambled oligodeoxynucleotide-treated mice described above. (D) LAF1 mice bearing Y1 tumors were injected with 5 mg/kg scrambled (n = 4) or antisense (n = 5) oligodeoxynucleotides three times every 24 h s.c. Tumors were removed from each mouse (indicated by serial numbers 1–4 for the scrambled group and 1–5 for the antisense group), and nuclear extracts prepared from the tumors were subjected to a Western blot analysis as described. The band corresponding to the DNA MeTase is indicated by an arrow. The amount of signal corresponding to the DNA MeTase (OD arbitrary units) was normalized to the level of total protein transferred onto the membrane as determined by Amido black staining and quantified by scanning (OD arbitrary units). The values obtained (OD of DNA MeTase signal divided by OD of the total protein staining) for the tumors extracted from each of the treated mice (serial number of mice in bold) were as follows: scrambled: 1, 2.2; 2, 3.1; 3, 2.7; and 4, 2.5: antisense: 1, 0.6; 2, 0.5; 3, 0.16; 4, 1.0; and 5, 2.9. (E) Average DNA MeTase level per group is plotted with the SEM. The difference between the scrambled and antisense groups was determined by a Student’s t test to be statistically significant (P < 0.05).

We determined the general toxic effects of in vivo DNA MeTase antisense oligodeoxynucleotide treatment vs. treatment with the control oligodeoxynucleotides. Blood parameters and weight loss of antisense-, reverse-, and scrambled-injected (20 mg/kg) tumor-bearing LAF1 mice (n = 5) were assayed. As shown in Table 1, there were no significant reductions in red blood cell count, hematocrit, or percentage of hemoglobin in DNA MeTase antisense-treated animals vs. controls. Similarly, platelet and white blood cell counts were not increased but rather were decreased slightly in antisense-treated animals (Table 1). There was no significant weight loss even though tumor load was decreased significantly in this experiment by DNA MeTase antisense oligodeoxynucleotides.

Table 1.

Hematological analysis of LAF1 mice treated with antisense or control oligodeoxynucleotides (20 mg/kg) for 30 days (n = 5).

| Treatment | Hematocrit | % hemoglobin | WBC | RBC | Platelets |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reverse | 17.2 ± 9.2 | 6.4 ± 3.3 | 59.6 ± 2.19 | 3.4 ± 2.19 | 514 ± 291 |

| Scrambled | 16.1 ± 2.5 | 6.16 ± 0.9 | 71.8 ± 21.9 | 2.99 ± .45 | 503.2 ± 104 |

| Antisense | 21.9 ± 9.5 | 7.44 ± 3.8 | 50.7 ± 33 | 4.4 ± 1.8 | 302 ± 95 |

WBC, RBC, and hematocrit in g/dcl. Numbers represent mean and SD.

These experiments demonstrated that in vivo treatment of tumor-bearing LAF1 mice with DNA MeTase antisense oligodeoxynucleotides can inhibit tumor growth, supporting the hypothesis that DNA MeTase is a critical component in maintaining the transformed state and that in vivo treatment with an antisense-based inhibitor of DNA MeTase can inhibit tumor growth.

DNA MeTase Antisense Oligodeoxynucleotide Inhibits DNA MeTase Levels, Induces Limited Demethylation of the Adrenocortical-Specific C21 Gene, and Reactivates It.

To determine whether injection of DNA MeTase antisense oligodeoxynucleotide can inhibit DNA MeTase activity, we treated tumor-bearing LAF1 mice for 3 days with either DNA MeTase antisense oligodeoxynucleotide (n = 5; 5 mg/kg) or the scrambled oligodeoxynucleotide (n = 4; 5 mg/kg) by s.c. injection near the tumor (1 cm) for 3 days. To limit (as much as possible) complicating, indirect factors that might have clouded the interpretation of data, we did not look at DNA methylation in tumors that were chronically treated. Tumors were harvested, nuclear extracts were prepared, and DNA MeTase levels in the nuclear extracts were determined by a Western blot analysis as described. The results of such an analysis are demonstrated in Fig. 2D, and the normalized average levels of DNA MeTase in each of the treatment groups plotted in Fig. 2E demonstrate a statistically significant reduction in DNA MeTase levels in antisense-treated animals (P < 0.05). The level of inhibition varied, however, from 90% inhibition in mouse number 3 in the group treated with antisense (Fig. 2D, lane 3) to no detectable inhibition in mouse number 5 (Fig. 2D, lane 5).

C21 is specifically expressed in the adrenal cortex, and the enzyme encoded by this gene, steroid 21 hydroxylase, is required for the synthesis of glucocorticoids, which is the main normal function of this tissue. The gene is expressed at very high levels in the adrenal cortex but is totally repressed and heavily methylated in Y1 tumor cells (41). No C21 mRNA is detected in Y1 cells even when the most sensitive assays, such as reverse transcriptase–PCR, are used (41). We have not observed any expression of C21 in Y1 cells in multiple Y1 cultures in the last decade under any conditions. We have suggested that this is a consequence of the increase in de novo DNA methylation activity in these cancer cells (41). Reexpression of C21 could serve as a good marker of demethylation and the reprogramming of Y1 cells to a nontransformed state.

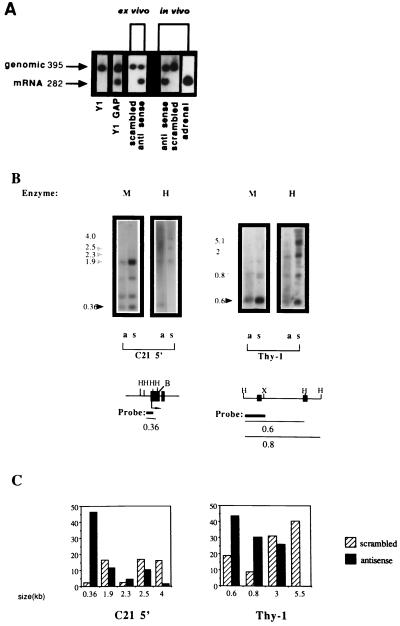

To address this question, we performed a reverse transcriptase–PCR analysis of C21 expression on RNA prepared from the following samples: Y1 cells treated with either antisense DNA MeTase or scrambled oligodeoxynucleotides (20 μM) ex vivo; a tumor isolated from a mouse treated with antisense oligodeoxynucleotides in vivo for 3 days (antisense 3 exhibited the highest reduction in DNA MeTase activity: 90%); and Y1 cells transfected with hGAP [which attenuates the Ras signaling pathway, resulting in inhibition of DNA MeTase activity and partial demethylation of the C21 gene (28)]. C21 expression was induced under all of these conditions (Fig. 3A). This is the first induction of C21 reexpression in Y1 cells under any conditions observed in our laboratory. These results strongly support the hypothesis that DNA MeTase antisense oligodeoxynucleotides induce a partial demethylation and reprogramming of gene expression in Y1 cells that is similar to that observed after attenuation of the Ras signaling pathway.

Figure 3.

Expression and demethylation of the C21 gene in Y1 tumors isolated from LAF1 mice treated with antisense oligodeoxynucleotides. (A) C21 expression was determined by reverse transcriptase–PCR amplification with C21-specific primers of total RNA isolated from Y1 cells, Y1GAP transfectants expressing hGAP (a GTPase- activating protein), an attenuator of Ras activity (28), Y1 cells treated with 20 μM of either scrambled oligodeoxynucleotide or DNA MeTase antisense oligodeoxynucleotides (ex vivo as indicated), Y1 tumors from LAF1 mice injected with either 5 mg/kg of scrambled or DNA MeTase antisense oligodeoxynucleotides (in vivo) as well as adrenal RNA. C21 plasmid DNA encoding the C21 gene (46) was included in the amplification reaction to control for nonspecific inhibition of amplification. The expected genomic and C21 mRNA amplification products are indicated by arrows. (B) DNA was extracted from Y1 tumors isolated from LAF1 mice injected with either scrambled oligodeoxynucleotides (scrambled 4, indicated as s) or antisense oligodeoxynucleotides (antisense 3, indicated as a) for 3 days as described. The DNA was subjected to HindIII digestion followed by either HpaII (H) (which cleaves the sequence CCGG when the internal C is not3 methylated) or MspI (M) (which cleaves the sequence CCGG even when the internal C is methylated) agarose gel fractionation (2.5%), Southern blotting analysis, and hybridization with the indicated probes. For the promoter region of the C21 gene, complete digestion of the gene should result in a 0.36-kb fragment (46), as indicated by the dark arrow. The partially methylated fragments are indicated by shaded arrows. The partial cleavage with MspI is a consequence of the fact that the MspI sites are nested within a HaeIII site. These sites are highly resistant to cleavage by MspI when fully or partially methylated, as described (47). For Thy-1, DNA prepared from the tumors indicated was subjected to a similar HpaII–MspI restriction enzyme analysis and hybridization with a 0.36 probe from the 5′ region of the thy-1 gene (48). The expected HpaII fragment is indicated by a dark arrow. Partially methylated fragments are indicated by shaded arrows. (Lower) Physical maps of the sequences analyzed for their methylation state. The first exons of the three genes are shown and are indicated as filled boxes, the probes used are indicated as thick lines, and the thin line indicates the expected nonmethylated and partially methylated HpaII fragments. (X, XbaI; B, BamHI). (C) Relative abundance of the HpaII fragments was determined by densitometry as described. The size in kilobases of the scanned fragments is indicated. The results are presented as intensity of a specific fragment as a percentage of the total intensity in all scanned fragments per lane.

To determine whether the 5′ promoter region of the C21 gene was demethylated in tumor DNA after antisense treatment, tumor DNA was subjected to MspI/HpaII restriction enzyme analysis, Southern blotting, and hybridization with a 5′ C21 probe [0.36-kb XbaI–BamHI fragment encoding the promoter region of the C21 gene (41)]. Hypomethylation of the two HpaII sites in the promoter region will result in a 0.36-kb fragment. As shown in Fig. 3B, the Y1 tumor that was extracted from a mouse (antisense 3) that was injected with antisense oligodeoxynucleotides in vivo exhibits an increase in the abundance (as determined by densitometric analysis; Fig. 3C) of the 0.36-kb HpaII fragment relative to the partially methylated fragments at 1.9, 2.5, and 4 kb compared with the control tumor. Demethylation of C21 is observed in other tumors injected with antisense (data not shown).

CpG island-containing genes are de novo methylated in tumor cells (13, 49–51). We therefore determined the state of methylation of a generally expressed CpG island-containing gene, thy-1, in mice treated with either antisense or control oligodeoxynucleotides. There was an increase in the relative abundance of the 600-bp HpaII fragment contained in the 5′ thy-1 CpG island (48) (Fig. 3B) and a decrease in the relative abundance of the partial HpaII fragments (≈3–5.5 kb) in tumors extracted from antisense-treated mice (labeled “a” in Fig. 3B) relative to the pattern observed in the control tumor (labeled “s” in Fig. 3B) (see Fig. 3C for quantification). These experiments demonstrated limited hypomethylation in tumor DNA in response to DNA MeTase antisense treatment in vivo.

DISCUSSION

The goal of this study was to test the hypothesis that tumorigenesis could be reversed by pharmacological inhibition of DNA MeTase activity and to suggest that DNA MeTase inhibitors could serve as potential anticancer agents. This study demonstrated that an antisense oligodeoxynucleotide directed against DNA MeTase mRNA can inhibit, in a dose-dependent manner, DNA MeTase mRNA expression, DNA MeTase activity, and tumorigenesis ex vivo and in vivo. Similar effects were not observed when a scrambled sequence was used. This is consistent with the hypothesis that the observed effects are a result of reduction in the level of DNA MeTase. The sequences used in our experiments did not bear the CG sites or G quartets that have been shown to bear nonantisense-related immunogenic and antitelomerase effects (52, 53). Although it is clear that phosphorothioate oligodeoxynucleotides might exhibit nonspecific antitumorigenic effects, our experiments revealed that the nonspecific and sequence-specific effects could be differentiated. One interesting question that was not addressed by this experiment is whether there is a critical size or level of tumor organization that is not treatable by DNA MeTase antisense inhibitors. Future studies will directly address this question.

Why are elevated levels of DNA MeTase critical for maintaining the cancer state? Three models have been suggested. (i) Elevated levels of DNA MeTase might result in disruption of the appropriate gene expression profile of a cell, leading to inactivation of tumor suppressor genes (17) and other genes that are characteristic of the differentiated state of the cell, such as C21 in Y1 cells (41). (ii) High levels of DNA MeTase might have a direct effect on origins of replication (18, 19). (iii) Methylated cytosines are hot spots for mutation, and deamination of methylated cytosines will result in C-T transition mutations (54).

Although more data are required to determine which of these mechanisms is involved in the genesis and maintenance of cancer, two issues are critical for the pharmacological and therapeutic application of DNA MeTase inhibitors. First, are the changes caused by aberrant methylation in carcinogenesis irreversible, as has been suggested (55), or are they reversible by pharmacological intervention? Min mice bearing a mutation in the homolog of the human repair-associated tumor suppressor gene APC were protected from formation of adenopolyps in the intestines when treated prophylactically with 5-azadeoxycytidine early after birth (55). The development of polyps could not be reversed when 5-azadeoxycytidine was applied later, suggesting an irreversible mechanism.

Second, is the aberrant methylation observed in cancer a consequence of the enhanced levels of DNA MeTase and therefore reversible by reducing the level of DNA MeTase (18, 19)? Although additional experiments will be required to demonstrate that similar results to those reported here can be obtained with cancers formed in the animal rather than in implanted tumors, our results lend support to the hypothesis that the effects of DNA MeTase induction are reversible and therefore suggest that DNA MeTase be a target for anticancer intervention.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Kirk Field for critical reading of the manuscript and his thoughtful suggestions. We also thank Deanna Collier, Vera Bozovic, and Johanne Theberge for excellent technical assistance. This research was supported by the National Cancer Institute Canada, by a contract with Hybridon, Inc. (Worcester, MA), and by MethylGene, Inc. (Montreal).

Footnotes

Abbreviation: DNA MeTase, DNA methyltransferase.

References

- 1.Razin A, Riggs A D. Science. 1980;210:604–610. doi: 10.1126/science.6254144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Razin A, Cedar H. Microbiol Rev. 1991;55:451–458. doi: 10.1128/mr.55.3.451-458.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tate P H, Bird A P. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 1993;3:226–231. doi: 10.1016/0959-437x(93)90027-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Adams R L, McKay E L, Craig L M, Burdon R H. Biochim Biophy Acta. 1979;561:345–57. doi: 10.1016/0005-2787(79)90143-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yisraeli J, Szyf M. In: DNA Methylation and Its Biological Significance. Razin A, Cedar H, Riggs A D, editors. New York: Springer; 1984. pp. 353–378. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Razin A, Kafri T. Prog Nucleic Acid Res Mol Biol. 1994;48:53–81. doi: 10.1016/s0079-6603(08)60853-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Szyf M. Biochem Cell Biol. 1991;69:764–767. doi: 10.1139/o91-117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gama-Sosa M A, Midgett R M, Slagel V A, Githens S, Kuo K C, Gehrke C W, Ehrlich M. Biochim. Biophys Acta. 1983;740:212–219. doi: 10.1016/0167-4781(83)90079-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Feinberg A P, Vogelstein B. Nature (London) 1983;301:89–92. doi: 10.1038/301089a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.de Bustros A, Nelkin B D, Silverman A, Ehrlich G, Poiesz B, Baylin S B. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1988;85:5693–5697. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.15.5693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nelkin B D, Przepiorka D, Burke P J, Thomas E D, Baylin S B. Blood. 1991;77:2431–2434. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Baylin S B, Makos M, Wu J J, Yen R W, de Bustros A, Vertino P, Nelkin B D. Cancer Cells. 1991;3:383–390. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Merlo A, Herman J G, Mao L, Lee D J, Gabrielson E, Burger P, Baylin S B, Sidransky D. Nat Med. 1995;1:686–692. doi: 10.1038/nm0795-686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ohtani-Fujita N, Fujita T, Aoike A, Osifchin N E, Robbins P D, Sakai T. Oncogene. 1993;8:1063–1067. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Herman J G, Latif F, Weng Y, Lerman M I, Zbar B, Liu S, Samid D, Duan D S, Gnarra J R, Linehan W M, Baylin S M. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:9700–9704. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.21.9700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Royer-Pokora B, Schneider S. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 1992;5:132–140. doi: 10.1002/gcc.2870050207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Makos-Wales M, Biel M A, El Deiry W, Nelkin B D, Issa J-P, Cavenee W K, Kuerbitz S J, Baylin S B. Nat Med. 1995;1:570–577. doi: 10.1038/nm0695-570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Szyf M. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 1994;15:233–238. doi: 10.1016/0165-6147(94)90317-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Szyf M. Pharmacol Ther. 1996;70:1–37. doi: 10.1016/0163-7258(96)00002-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Szyf M, Avraham-Haetzni K, Reifman A, Shlomai J, Kaplan F, Oppenheim A, Razin A. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1984;81:3278–3282. doi: 10.1073/pnas.81.11.3278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kautiainen T L, Jones P A. J Biol Chem. 1986;261:1594–1598. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.el-Deiry W S, Nelkin B D, Celano P, Yen R W, Falco J P, Hamilton S R, Baylin S B. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:3470–3474. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.8.3470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Belinsky S A, Nikula K J, Baylin S B, Issa J P J. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:4045–4050. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.9.4045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wu J, Issa J P, Herman J, Bassett D E, Jr, Nelkin B D, Baylin S B. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:8891–8895. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.19.8891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.MacLeod A R, Szyf M. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:8037–8043. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.14.8037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rouleau J, Tanigawa G, Szyf M. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:7368–7377. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rouleau J, MacLeod A R, Szyf M. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:1595–1601. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.4.1595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.MacLeod A R, Rouleau J, Szyf M. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:11327–11337. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.19.11327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Szyf M, Theberge J, Bozovic V. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:12690–12696. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.21.12690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jones P A. Cell. 1985;40:485–486. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(85)90192-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tamame M, Antequera F, Villanueva J R, Santos T. Mol Cell Biol. 1983;3:2287–2297. doi: 10.1128/mcb.3.12.2287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Juttermann R, Li E, Jaenisch R. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:11797–11801. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.25.11797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dean N M, McKay R. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:11762–11766. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.24.11762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yasumura Y, Buonsassisi V, Sato G. Cancer Res. 1966;26:529–535. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schwab M, Alitalo K, Varmus H E, Bishop M. Nature (London) 1983;303:497–501. doi: 10.1038/303497a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Szyf M, Kaplan F, Mann V, Gilloh H, Kedar E, Razin A. J Biol Chem. 1985;260:8653–8656. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Szyf M, Bozovic V, Tanigawa G. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:10027–10030. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ausubel F M, Kingston R, Moore D, Seidman J, Smith J, Struhl K, editors. Current Protocols in Molecular Biology. New York: Wiley; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Freedman V H, Shin S. Cell. 1974;3:355–359. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(74)90050-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mayer R J, Walker J H. Immunochemical Methods in Cell and Molecular Biology. London: Academic; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Szyf M, Milstone D S, Schimmer B P, Parker K L, Seidman J G. Mol Endocrinol. 1990;4:1144–1152. doi: 10.1210/mend-4-8-1144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Plumb J A, Wishart C, Setanoians A, Morrison J G, Hamilton T, Bicknell S R, Kaye S B. Biochem Pharmacol. 1994;47:257–266. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(94)90015-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Szyf M, Rouleau J, Theberge J, Bozovic V. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:12831–12836. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bestor T H, Laudano A, Mattaliano R, Ingram V. J Mol Biol. 1988;203:971–983. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(88)90122-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Walder R Y, Walder J A. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1988;85:5011–5015. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.14.5011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Szyf M, Schimmer B P, Seidman J G. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1989;86:6853–6857. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.18.6853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Keshet E, Cedar H. Nucleic Acids Res. 1983;11:3571–3580. doi: 10.1093/nar/11.11.3571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Szyf M, Tanigawa G, McCarthy P L., Jr Mol Cell Biol. 1990;10:4396–4340. doi: 10.1128/mcb.10.8.4396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Jones P A, Wolkowicz M J, Rideout W M, III, Gonzales F A, Marziasz C M, Coetzee G A, Tapscott S J. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:6117–6121. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.16.6117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Issa J P, Zehnbauer B A, Civin C I, Collector M I, Sharkis S J, Davidson N E, Kaufmann S H, Baylin S B. Cancer Res. 1996;56:973–977. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Herman J G, Jen J, Merlo A, Baylin S B. Cancer Res. 1996;56:722–727. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zahler A M, Williamson J R, Cech T R, Prescott DM. Nature (London) 1991;350:718–720. doi: 10.1038/350718a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Krieg A M, Yi A K, Matson S, Waldschmidt T J, Bishop G A, Teasdale R, Koretzky G A, Klinman D M. Nature (London) 1995;374:546–549. doi: 10.1038/374546a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Rideout W M, III, Coetzee G A, Olumi A F, Jones P A. Science. 1990;249:1288–1290. doi: 10.1126/science.1697983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Laird P W, Jacksongrusby L, Fazeli A, Dickinson S L, Jung W E, Li E, Weinberg R A, Jaenisch R. Cell. 1995;81:197–205. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90329-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]