Abstract

Objectives

To explore the nature of corporate gifts directed at PharmD programs and pharmacy student activities and the perceptions of administrators about the potential influences of such gifts.

Methods

A verbally administered survey of administrative officials at 11 US colleges and schools of pharmacy was conducted and responses were analyzed.

Results

All respondents indicated accepting corporate gifts or sponsorships for student-related activities in the form of money, grants, scholarships, meals, trinkets, and support for special events, and cited many advantages to corporate partner relationships. Approximately half of the respondents believed that real or potential problems could occur from accepting corporate gifts. Forty-four percent of respondents agreed or strongly agreed that corporate contributions could influence college or school administration. Sixty-one percent agreed or strongly agreed that donations were likely to influence students.

Conclusions

Corporate gifts do influence college and school of administration and students. Policies should be in place to manage this influence appropriately.

Keywords: development, gifts, fundraising, corporate influence, corporate partnerships

INTRODUCTION

As the shortage of pharmacists has become acute over the last decade, corporations (including retail pharmacy chains), the pharmaceutical industry, and hospitals increasingly seek to influence doctor of pharmacy (PharmD) students' career choices in a variety of ways during their professional programs. The more traditional forms of influence have included “gifts” such as meals and trinkets provided at recruitment fairs and seminars, scholarships to gain corporate name recognition among students, funds to student organizations that support travel to national meetings, and donations to improve school facilities in exchange for naming rights. As the demand for pharmacists has risen, there is increasing anecdotal evidence that more direct influences such as tuition support, signing bonuses, loan repayment support, and even automobiles are being offered to students who agree to join a company after graduation. Students are being recruited earlier in the education process and, with double-digit increases in tuition, the offers are becoming economically more attractive. Colleges and schools may be concerned that students are likely to make inappropriate or poorly considered career-related decisions, and pharmacy school administrators may question the need to manage such influences on their student body.

Some of these sources of direct influence fall outside the purview of academic institutions (eg, tuition support offers to pharmacy interns made in the workplace); however, many are imbedded in academic programs or institutional events. As a result, it is important to consider the degree to which sponsorship and gift giving can influence students as well as institutions. In a time of dwindling state-supported financial resources and escalating tuition, corporate gifts are an important and necessary component to the academic enterprise and its mission. Balancing financial needs with appropriate exposure and access to all sectors of pharmacy, and managing the influence of this exposure, are increasing challenges to academic administrators. The current literature does not address the extent of corporate influence on pharmacy students or how colleges and schools of pharmacy are managing these external influences on their students. Research looking at the influence exerted by the pharmaceutical industry on medical residents and practitioners may offer a surrogate marker suggesting that gifts and sponsorships are likely sources of influence.1-3 Therefore, it is important to analyze this topic and explore how and to what extent colleges and schools of pharmacy are able to manage this issue.

The primary goal of this exploratory study is to identify the extent to which a small sample of public and private colleges and schools received gifts from private corporations related to their PharmD programs, the nature of the gifts, and the perceptions of the colleges' and schools' administrators and development officers about potential influences of such gift receiving.

Specific objectives of this study were to:

identify the type and size of gifts received by colleges and schools of pharmacy from private corporations (eg, pharmaceutical industry, community pharmacy chains, hospitals) supporting PharmD student educational or extracurricular initiatives;

document perceptions of academic administrators regarding the potential influences of these gifts;

identify approaches colleges and schools had adopted to manage potential influence from corporate gifts; and

identify core issues colleges and schools should consider when developing policies related to corporate giving and PharmD education.

This multi-center exploratory study was conducted by the authors as part of the 2005-2006 AACP Academic Leadership Fellows Program. The data gathered will be used to suggest strategies to administrators to manage the potential corporate influence on pharmacy students.

METHODS

A qualitative inquiry process was employed to explore the administrative and social problem of corporate influence on pharmacy students. Coauthors recruited key administrators from their own colleges and schools and one additional school to respond to issues embedded in the study objectives. The goal was to analyze detailed views expressed by these informants based on the experiences of their colleges and schools. Eleven colleges and schools of pharmacy were recruited to participate in this study representing a mix of public and private colleges and schools from different regions of the country. Three administrators were surveyed at each school including the dean, development director, and a third administrator who was either an associate or assistant dean working in academic or student affairs. These individuals were considered to have decision-making responsibility related to receipt of gifts and sponsorships. A structured interview questionnaire was developed consisting of open as well as closed-ended questions.

The questionnaire was revised by several rounds of iteration as the content validity was assessed by coauthors with expertise in survey research and the group's dean facilitator. The resulting questionnaire was pilot-tested by administrators from a university not participating in the study. Based on feedback received from pilot-study participants, the questionnaire was revised to clarify ambiguous questions and improve focus on the study objectives. The final questionnaire had 19 questions and a study disclosure statement preceding the questions. Investigational Review Board approval to conduct the questionnaire was obtained from Howard University, the University of Illinois at Chicago, University of Kentucky, University of Minnesota, University of Missouri-Kansas City, and West Virginia University.

Following IRB approval, data collection began in late December 2005 and ended in mid-February 2006. Administrators were surveyed in person or by telephone, depending on the location of the colleges and schools. The transcribed interview data collected from all the interviews were first collated and grouped by type of respondent: dean, assistant or associate dean, and development officer. Results of closed-ended questions were tabulated by type of respondent. Answers to open-ended questions were grouped together using common content or themes underlying the responses. Whenever appropriate, these themes were indexed to the responses to closed-ended questions.

RESULTS

Twenty-nine administrators representing 11 colleges and schools of pharmacy completed the survey instrument. Responses were received from 9 deans, 12 associate/assistant deans, and 8 development directors. All respondents indicated that their colleges and schools have accepted corporate gifts or sponsorships for student-related activities in the form of monetary gifts, grants, scholarships, meals, trinkets, special events and, to a lesser extent, textbook support. Travel support enabling students to attend professional meetings was also noted as a sponsored activity.

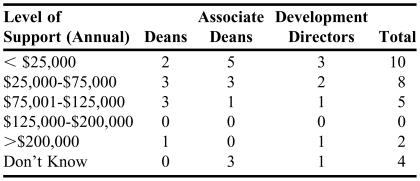

Respondents reported donations ranging from $25,000-$200,000 annually (Table 1). Most of the respondents reporting donations >$75,000 represented private colleges and schools. Nearly all respondents indicated that community pharmacy chain organizations were the major source of financial support, representing more than 50% of all gifts and sponsorships received in support of student initiatives.

Table 1.

Annual Value of Gifts and Sponsorships Supporting PharmD Student Initiatives (N = 29)

Respondents were also asked whether their school has attributed “naming rights” to any physical space or equipment used primarily by pharmacy students secondary to corporate sponsorship (eg, naming of lecture hall, laboratory space, trophy area, student or faculty lounge). Ten of the 12 responding institutions reported that they had attributed naming rights to some item within their college or school.

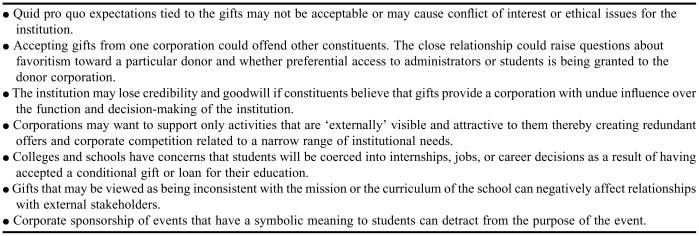

School administrators were asked if they have experienced problems or if they perceived the potential for problems arising from accepting corporate gifts. Fifty-five percent of the respondents indicated having experienced problems or perceived that there could be problems. Examples of real or potential problems identified by the respondents are provided in Table 2.

Table 2.

Perceived Problems Associated With Acceptance of Corporate Gifts by Colleges and Schools of Pharmacy

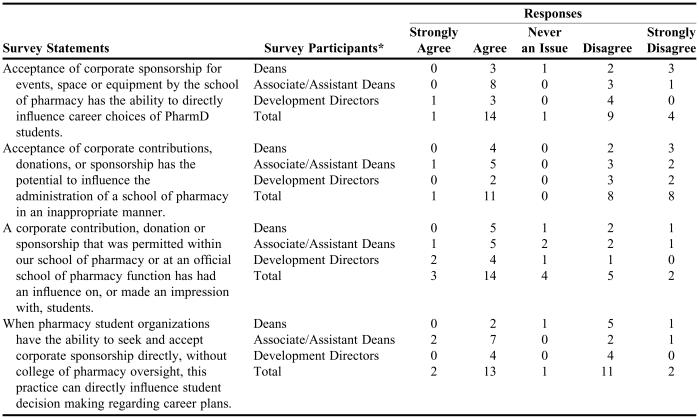

In examining whether the acceptance of corporate contributions, donations, or sponsorship had the potential to influence a pharmacy school's administration, there was little consensus identified in the responses of deans and associate/assistant deans. Forty-four percent of respondents agreed or strongly agreed that contributions could influence an administration, while 56% disagreed or strongly disagreed (Table 3). In contrast, administrators frequently expressed concern that corporate contributions allowed by the college or school or at an official school function can have an influence on students (Table 3).

Table 3.

Perceptions of School Administrators on Corporate Giving and Influence

*Deans (n = 9), Associate/Assistant Deans (n = 12), Development Directors (n = 8)

Respondents were asked to indicate if they had ever turned down a corporate gift because they thought it was inappropriate. Three of 9 deans, 2 of 12 assistant/associate deans, and 2 of 8 development directors indicated that they had turned down a gift that they thought was inappropriate. Respondents were also asked whether they believed there are circumstances when a college or school of pharmacy should not accept any form of donation or sponsorship with the majority of respondents (14) answering “yes” to this question, while 5 administrators indicated “not sure.”

Perceptions regarding student groups that seek corporate sponsorship directly, without institutional involvement, were also addressed. Seventy-five percent of respondents indicated that they perceived potential problems with students taking on this activity. The concerns centered on 2 primary issues: (1) sponsors may not understand whether they are contributing to a student organization or to the college or school as a whole; and (2) small requests for gifts by student groups might undermine efforts to secure larger gifts to an institution from the same sponsor. When respondents were asked whether allowing student groups to directly seek corporate sponsorship could influence students' career planning, opinions varied (Table 3).

To clarify perceptions and issues related to corporate sponsorships, respondents were asked to consider the following hypothetical case scenario:

Your College is planning its “White Coat Ceremony” and a sponsor informs you that they are interested in sponsoring this event. In your organization, this ceremony is for first year students and the coats are worn primarily during their work in your College's skills lab. They are willing to cover all costs for the ceremony including room rental, refreshments, coats for each student, etc. The anticipated costs of the event are approximately $5000. In return for sponsorship, they ask for the following forms of recognition: 1) recognition in the event's program; 2) a speaker to address the group (they indicate this could be the Keynote Speaker, but does not need to be); and 3) their corporate logo on the coats.

When asked “How would your organization engage in decision making around this offer?” the deans, associate deans, and development directors agreed that the final decision would be made by the dean. However, in the majority of colleges and schools, the deans would use an executive committee or other leadership group to assist in making decisions about such an offer.

When asked how their school would personally respond to this offer, deans said they would accept the sponsorship with acknowledgement in the program, but they preferred to choose their own speaker and would not allow the sponsor to put logos on the laboratory coats. Three of the associate deans said they would probably refuse the offer primarily because of concerns about the request to put a logo on the white coats. The remainder of the associate deans agreed with the deans that recognition of the sponsorship was acceptable but allowing the sponsor to choose the speaker or put logos on the coats would be unacceptable. One associate dean would consider allowing the logo but stated that the students would only be able to wear these coats in certain situations that would restrict the usefulness of the coats.

When asked what issues or concerns the deans would identify in the scenario, most of the deans listed the use of logos on student white coats as an issue. The logos were considered unacceptable because it reflects an advertising or marketing strategy rather than a partnership in education offer. The associate deans also named the logo as the primary concern, indicating that its use would suggest an inappropriate relationship with the sponsor that would be objectionable to other corporate partners. Three of the associate deans also listed the corporate-chosen speaker as an issue, citing possible bias in the presentation and a desire to have control over the message delivered by the speaker. While most development directors expressed similar concerns as the deans, this group was somewhat more positive toward accepting a speaker. One development director stated that the size of the gift might influence acceptance of a speaker and another believed that accepting the speaker might increase the credibility of the program by demonstrating that corporate America has respect for the type of students we educate.

Given the current climate favoring university fundraising campaigns, policies have been enacted for most institutions in an effort to govern the legal issues of corporate sponsorship. Seventy-three percent (n = 8) of participating colleges and schools reported either having a policy in place or in development. In 2 cases, this policy was not specific to the college of pharmacy, but a University-level policy.

When asked whether any specific factor led to the development of school policies on corporate giving, respondents identified 3 factors: (1) an effort to maximize the college and/or the university's campaign giving; (2) recognition of the need for a structured process to track and acknowledge corporate donors; and (3) a perceived need to manage exposure of students to donors with sufficient institutional oversight. Some colleges and schools favored a policy mandating that all gifts be given to a general pool overseen by the school's administration, thereby preventing inappropriate direct student influence on career decisions.

Nearly all respondents indicated that their student organizations seek corporate sponsorship for activities without significant oversight from the school. When asked whether their college or school had policies governing such activities, the answers were equally split with 10 “yes,” 10 “no,” and 10 “in progress” or “not sure.” A few administrators gave conflicting answers to this question. College or school policies governing funding that exceeds a predetermined dollar amount may have led to different answers from administrators at the same institution. There were also ambiguities surrounding this question that may be attributed to whether the policy was written or existed as an “unwritten rule.”

Finally, administrators were asked about the existence of any formal career-planning initiatives managed by the institution that may offset influence on student career planning through corporate sponsorships and donations. Fourteen respondents indicated that they do offer formal career-planning activities within their institution, 11 indicated that they do not, and 3 respondents were unsure. While half of respondents indicated that they offered programs, when asked to describe the type and scope of these, it was clear that availability of these programs is quite limited. Having students complete the Career Pathway Evaluation Program offered by the American Pharmacists Association4 was the most frequently cited activity. A few colleges and schools mentioned offering “career days,” limited mentoring programs, or an “introduction to pharmacy” course.

DISCUSSION

The majority of the literature describing corporate influences on faculty members and students in academic medical centers deals with the influence of the pharmaceutical industry on physician-faculty members. The studies have primarily concluded that the faculty-industry relationship affects prescribing by physicians as well as formulary decisions within the institutions. The studies suggest that these issues should be addressed through educational programs and establishing internal policies to govern the relationship.1,5-12 While these relationships are not of the same type addressed in this project, there are correlations between the work in managing influence in academic medical centers and the project and outcomes described in this paper.

With respect to policies related to gifts, a position paper on physician-industry relations developed by the American College of Physicians-American Society of Internal Medicine established a set of core principles for external funding and relationships.5 Of those outlined in this report, the following principles are likely relevant for pharmacy education: (1) the school's mission and values should be the driving force behind all external relationships and funding arrangements; (2) those who represent the colleges and schools in external relationships must adhere to these values and ethical principles and promote professionalism in these arrangements; (3) full disclosure of the nature of these external financial arrangements should occur on a regular basis to allow all parties to assess the potential for real or perceived conflicts of interest; (4) students should benefit from these relationships by enhancing their professionalism and educational experience; and (5) colleges and schools should monitor their reliance on outside sources of funding and ensure that core activities could continue in the absence of this support.

Several studies have specifically addressed the corporate influence on medical students and residents. A 2005 study reviewed the medical literature for the time period 1996-2004 for articles addressing the interaction between doctors in training and the pharmaceutical industry.3 Conclusions drawn from the 44 articles included in the study suggest a significant influence by the pharmaceutical industry on resident behavior. Trainees believed that their own behavior was not affected by gifts and promotions by the industry although the behavior of other residents could be affected. The current survey found similar results. The majority of administrators disagreed or strongly disagreed that corporate contributions could influence an administration. However, the majority of administrators felt that students were likely to be influenced by the same contributions.

Research into the influence of gifts on health professionals has shown that small gifts can significantly influence the recipient who has difficulty remaining objective and feels the impulse to reciprocate.1-2 Likewise, the gift giver has an expectation that the recipient will reciprocate even though no overt strings are attached to the gift.2 Again, while this work is focused on physicians and prescribing influences, it is important to note the relationship between acceptance of small gifts and influence on behavior. Recognizing this relationship is an important consideration when developing policies within colleges and schools of pharmacy that address corporate giving and the relationship between students and potential employers.

In 2003, a group of health professions faculty members surveyed students at Creighton University to assess their knowledge and attitudes about the pharmaceutical industry.13 The study concluded that students’ attitudes about the industry are determined prior to graduation. Student practitioners who will have prescriptive rights (medical and nurse practitioner students) interacted more frequently with pharmaceutical sales representatives than other health professions students and had more positive attitudes about pharmaceutical sales representatives than other students. Some administrators in this study commented that one benefit of corporate giving is the opportunity to build relationships between colleges and schools and corporations and to introduce the students to the corporations. One implication of the Creighton study is that access to students during their training is critical to corporations seeking to establish a positive image with practicing pharmacists.

Only 1 published study examined the relationship between pharmaceutical industry giving and pharmacy students.14 In 1993, students at 2 Texas pharmacy colleges and schools were surveyed to determine whether pharmaceutical industry contributions promoted a good company image to the students, whether students recognized the contributions and to identify which companies were most well known to Texas students. The study concluded that Eli Lilly was the most well-known company by the Texas students. While the authors could not determine how Eli Lilly had achieved a strong reputation with the students, the following facts were noted. Eli Lilly was listed among the top 3 companies by scholarships provided to students, availability of summer internships, and sending representatives to the school to talk to students. Eli Lilly was also ranked among the top 4 pharmaceutical companies where students would like to seek employment after graduation. While this study looked specifically at the pharmaceutical industry, it is feasible to assume that this phenomenon could apply to the image of pharmacy chain organizations.

In an effort to respond to the increasing requests by corporations to sponsor activities for students within the academic setting, some colleges and schools of pharmacy are developing policies to govern and standardize corporate giving. The University of Wisconsin's Madison Health Sciences Council endorsed a policy in 2005 to avoid conflicts of interest and to assure the integrity of the interactions between health professions students and the healthcare industry including prospective employers.15 According to this policy, healthcare industry representatives and prospective employers are to interact with health professions students only during educational meetings and approved placement service sessions. In addition, companies are encouraged to donate monies indirectly through funds that support students and student activities.

Purdue University School of Pharmacy has developed a Corporate Partner Program as a mechanism to partner with companies to provide support for doctor of pharmacy students and school activities.16 The program is structured to solicit corporate sponsors once each year for a donation to scholarships and school activities. The sponsors have the opportunity to interact with students during a number of structured activities that occur during the school year. Oregon State University has developed a similar program called the Pharmacy Partners Program.17 An annual donation to the Dean's Pharmacy Partners Fund permits the donor to have preferred status in student recruiting, visibility among faculty and students and improved communication with the college. The partners fund is used for educational program enhancements and enabling faculty productivity.

Recommendations Regarding Corporate Gifts

Based on the review of the literature looking at the corporate influence on health professionals as well as the results of this survey, the authors believe that the potential for corporate gifts to influence student pharmacists is real and may occur with only a small donation. Administrators are encouraged to acknowledge and actively manage this issue. As a result, it is recommended that all colleges and schools develop policies governing corporate donations that directly affect pharmacy students. Policies should be easy to understand and easily accessible to all (eg, via the college/school intranet). School administrators, faculty members, student organization advisors, and leaders should be made aware of these guidelines especially when they first join the school. A school official who is knowledgeable about these guidelines (eg, the development officer) should be identified to serve as a resource for other faculty members who may have questions or concerns.

Additional recommendations to colleges and schools of pharmacy include:

Prospectively share policies with potential donors.

Most donors have their own guidelines and ethical considerations for gift giving. However, sharing the school's developmental plan and established policies for gift solicitation and receiving with potential donors will diminish the chances of inappropriate conduct or offers from corporations.

Have a fundraising/development strategic plan with clearly defined goals and a description of activities to be performed.

Make sure that the plan has broad support and endorsement of key constituent groups. Have an advisory panel consisting of representatives from different constituent groups who can advise the school administration as needed. The plan should provide any donor an opportunity to assist or contribute at whatever financial level feasible for them.

Be proactive about anticipating problems associated with gift solicitation and receiving activities.

Work with University development professionals to develop protocols for dealing with unanticipated situations or undesirable offers of gifts. Not all gifts are desirable, eg, offers of old books, journals, pharmacy artifacts of little or no value that donors want to donate for tax benefits; gifts from organizations where conditions of the gift are unacceptable to the school or college; or gifts from organizations whose business is not consistent with the ideals of the pharmacy profession or whose practices are suspect.

Use the “headline” litmus test when considering gifts.

Administrators who solicit or accept gifts should ask themselves the question: If receipt of this gift/donation appeared as a news item on the front page of a newspaper, would it embarrass the school or upset another constituent?

At the beginning of each academic year, student organization leaders should be informed about school policies related to fundraising.

This would include how to report the group's fundraising activities, what activities can be supported through fund raising or gift solicitations, what can be solicited from corporations, what representations (or disclosures) must be made to corporations, and how any gifts received should be properly documented and acknowledged. Student leaders should bear the responsibility of all fund raising done by members of their organization for in-school as well as outside-of school activities. Organizations must seek permission to conduct fundraising or gift solicitation activities and appropriately report all gifts received. They must recognize that sometimes a corporation or group of constituents may be off-limits to them because of the school's larger developmental interest.

Consider establishing a “gift pool.”

To prevent any one donor from exerting an undue influence on students, establish a pool for gifts received from all donors and use funds from that for the designated activity. Ensure that all donors are acknowledged.

Consider issues of equality and transparency.

Gift solicitation should be as uniform as possible across all potential donors and gift receiving should be as transparent as possible to all school constituents.

Recognize that some sources of influence are not within a school's purview.

For example, a chain pharmacy organization may make an offer of tuition payment to a pharmacy technician or intern in exchange for their agreement to work for the organization upon graduation. Preadmission counseling and school web sites can provide information to incoming students about the potential drawbacks of entering into such binding agreements. Students can be advised to read the fine print of such agreements carefully and seek advice/counseling from school officials before signing such agreements.

Develop formal and substantial career-planning initiatives in curricula to offset the effects of corporate influence on career decision making.

Colleges and schools should have elective courses or internship opportunities that can expose students to a variety of pharmacy practice areas. Individualized career counseling and planning opportunities should be available from the beginning of the pharmacy education process.

CONCLUSION

Corporate influence on colleges and schools of pharmacy and their students does exist and policies should be in place to manage this influence appropriately. There are a number of strategies that have or could be used by administrators to minimize the chance that career decisions made by pharmacy students are overtly influenced by corporate donations while administrators continue to seek corporate partnerships that support the fiscal needs of the academic enterprise.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors wish to acknowledge the expertise, guidance and mentorship provided by Jeanette C. Roberts, Dean, School of Pharmacy, University of Wisconsin-Madison during the completion of this project and throughout the Academic Leadership Fellows Program.

REFERENCES

- 1.Halperin EC, Hutchinson P, Barrier RC., Jr A population-based study of the prevalence and influence of gifts to radiation oncologists from pharmaceutical companies and medical equipment manufacturers. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2004;59:1477–83. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2004.01.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dana J, Lowenstein G. A social science perspective on gifts to physicians from industry. JAMA. 2003;290:252–5. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.2.252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zipkin DA, Steinman MA. Interactions between pharmaceutical representatives and doctors in training. A thematic review. J Gen Intern Med. 2005;20:777–86. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2005.0134.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Career Pathway Evaluation Program for Pharmacy Professionals, American Pharmacists Association. Available at https://www.aphanet.org/pathways/pathways.html. Accessed November 15, 2006.

- 5.Coyle SL. Physician-industry relations. Part 1: individual physicians. Ann Intern Med. 2002;136:396–402. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-136-5-200203050-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Coyle SL. Physician-industry relations. Part 2: organizational issues. Ann Intern Med. 2002;136:403–6. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-136-5-200203050-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Breen KJ. The medical profession and the pharmaceutical industry: when will we open our eyes? Med J Aust. 2004;180:409–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Angell M. Is academic medicine for sale? New Engl J Med. 2000;342:1516–8. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200005183422009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lewis S, Baird P, Evans RG, et al. Dancing with the porcupine: rules for governing the university-industry relationship. [Sep 18 2001];Canadian Medical Association Journal. 165:783–5. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Campbell EG, Moy B, Feibelmann S, Weissman JS, Blumenthal D. Institutional academic industry relationship: results of interviews with university leaders. Account Res. 2004;11:103–18. doi: 10.1080/03050620490512296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brett AS, Burr W, Moloo J. Are gifts from pharmaceutical companies ethically problematic? A survey of physicians. Arch Intern Med. 2003;163:2213–8. doi: 10.1001/archinte.163.18.2213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Coleman DL, Kazdin AE, Miller LA, Morrow JS, Udelsman R. Guidelines for interactions between clinical faculty and the pharmaceutical industry: one medical school's approach. Academic Med. 2006;81:154–60. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200602000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Monaghan MS, Galt K, Turner PD, Houghton, et al. Student understanding of the relationship between the health professions and the pharmaceutical industry. Teach Learn Med. 2003;15:14–20. doi: 10.1207/S15328015TLM1501_04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Charupatanapong N, Rascatti K. Pharmaceutical industry contributions to Texas pharmacy students: is it worth it? Texas Pharm. 1993;112:17. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Policy on Healthcare Industry Representatives and Prospective Employers: UW-Madison Health Sciences Council; 2005. Available at: http://www.pharmacy.wisc.edu/career/Fair/IndustryRepsHSLC.pdf. Accessed July 11, 2007.

- 16. Corporate Partner Program. West Lafayette, Ind. Purdue School of Pharmacy and Pharmaceutical Sciences. Available at: http://alumni.pharmacy.purdue.edu/pages/phil/phil_partner.shtml. Accesssed July 11, 2007.

- 17. Pharmacy Partners Program, Corvallis OR, Oregon State University College of Pharmacy. Available at: http://pharmacy.oregonstate.edu/partners. Accessed July 11, 2007.