Abstract

Objective

To teach pharmacy students how to apply transactional analysis and personality assessment to patient counseling to improve communication.

Design

A lecture series for a required pharmacy communications class was developed to teach pharmacy students how to apply transactional analysis and personality assessment to patient counseling. Students were asked to apply these techniques and to report their experiences. A personality self-assessment was also conducted.

Assessment

After attending the lecture series, students were able to apply the techniques and demonstrated an understanding of the psychological factors that may affect patient communication, an appreciation for the diversity created by different personality types, the ability to engage patients based on adult-to-adult interaction cues, and the ability to adapt the interactive patient counseling model to different personality traits.

Conclusion

Students gained a greater awareness of transactional analysis and personality assessment by applying these concepts. This understanding will help students communicate more effectively with patients.

Keywords: communication, transactional analysis, personality assessment, patient counseling

INTRODUCTION

Pharmacy students are expected to develop technical, diagnostic, human, and conceptual skills as they progress through doctor of pharmacy programs. Pharmacists are expected to communicate with patients, peers, other health care professionals, employers, and employees. One opportunity for human skill development is the communications course included in most college of pharmacy curricula.1 The American Council on Pharmaceutical Education's Accreditation Standards and Guidelines and the American Association of Colleges of Pharmacy's (AACP) Center for the Advancement of Pharmaceutical Education (CAPE) Educational Outcomes include communications skills as assessment and outcome criteria. Specifically, AACP recommends that students have the ability to “Provide counseling to patients and/or caregivers relative to proper therapeutic self-management.”

To promote “therapeutic self-management” means that the patient is psychologically engaged in the counseling process. Pharmaceutical interventions through patient counseling are more effective if patients are motivated to participate in their therapy. More than 50% of patients do not take their medications as directed.2 To help students communicate with patients with a goal of generating therapeutic self-management, a lecture series, Psychological Aspects of Patient Counseling (PAPC), is included in the Patient Counseling and Communications course at the University of Louisiana at Monroe (ULM) College of Pharmacy.

Developing human communications skills to enable pharmacists to effectively communicate with patients as well as other health care providers is the overall objective of the Patient Counseling and Communications course. The instructional design of this course includes: professional requirements to counsel patients; communications model; Interactive Patient Counseling Model; barriers to communication; motivational interviewing; cultural diversity; psychological aspects of patient counseling (PAPC); behavioral disorders; and a practice laboratory. Third-professional year pharmacy students are required to take the 2-hour course, which is presented with lecture; a required text (Communication Skills in Pharmacy Practice by Tindall, Beardsley, and Kimberlin); and interactive learning through application. Ten weeks of the course are devoted to developing a knowledge base in effective communication. The last 4 weeks of the course involve practicing patient communication through case scenarios. The focus of this paper is the PAPC lecture series that is a part of this course.

In the PAPC lecture series, students are presented with the concept of Transactional Analysis and 2 methods of personality assessment. The objectives of the PAPC segment of the Patient Counseling and Communications course are to help students:

understand psychological factors that may affect patient communication

appreciate diversity created by different personality types

engage patients based on adult-to-adult interaction cues, and

adapt the interactive patient counseling model to different personality traits.

DESIGN

The PAPC lecture series was included as part of the Patient Counseling and Communications course in fall 2006. The series included transactional analysis and personality assessment to promote students' knowledge of psychological differences that impact communication.

Methodolgies Presented in the PAPC Segment

To accomplish the objectives for the PAPC segment, 3 methodologies were presented and discussed in class: transactional analysis, Myers-Briggs Type Indicator, and psychogeometrics. Transactional analysis is a social psychology developed by Eric Berne in the 1950s and used to improve communication. Berne was trained in psychoanalysis and developed a way to improve communications with patients. He based his theory on a contractual approach to “an explicit bilateral commitment to a well-defined course of action.”3 Berne used ego states to explain how individuals relate to each other. The 3 basic states are parent, adult, and child. The parent ego state is based on thoughts and feelings copied from parents or parent figures; the adult ego state relates to thoughts and feelings in the here and now; and the child ego state is based on thoughts and feelings replayed from childhood. Based on the assumption that patients will in turn accept greater responsibility for medication therapy, it is recommended to students that pharmacists relate to patients in the adult ego state. This ego state is based on the ability to think and determine actions for ourselves.

To effectively communicate with a patient in the adult ego state means that the pharmacist has to develop dialogue directed at the adult ego state. Considering that the patient counseling session is controlled by the pharmacist utilizing an interactive patient counseling model means that the development of an adult-to-adult transaction is within the control of the pharmacist. If the pharmacist does not understand the concept of transactional analysis, he or she may find that the counseling session develops into a parent-child transaction with less than optimal results. If the pharmacist assumes a parent ego state, he or she may resort to being a negative controlling parent or negative nurturing parent. If the patient is in an adult ego state and does not respond as a child then, according to TA theory, communication breaks down or the patient becomes a negative adaptive child or negative free child. This is considered an ineffective method of communication or a crossed transaction. A crossed transaction occurs when a message is sent in one ego state but received and responded to in a different ego state.

Because crossed transactions result in ineffective communication, students were asked to practice sending and receiving responses to hear and feel when transactions cross or when they are successful. This successful communication is necessary for the pharmacist/patient relationship to form.6 The parent ego state involves judgmental statements such as “You will never get better if you don't take your medication correctly.” Child ego may involve physical or verbal language such as a whining voice or excuses for not taking medication as directed. Adult ego communication is definitive communication that is straight-forward and nonthreatening. It is factual, analytical, and for the most part void of emotion. In contrast, starting a sentence with “You need” or “You should” sends an authoritative parent message. If the receiving person is in an adult ego state, communication breaks down. An example of an adult statement for patient counseling is “This medication is to be taken every 4 hours” instead of “You need to take this medication every 4 hours.” While the differences seem minor, they may generate different psychological reactions.

Another dimension to PACP is personality assessment. Selected for this exercise are Myers-Briggs Type Indicator (MBTI) and psychogeometrics. The MBTI is a personality test that was developed during World War II by Katherine Cook Briggs and her daughter Isabel Briggs Myers based on the theories of Carl Jung.4 The MBTI focuses on 4 pairs of contrasting psychological functions. This theory is based on the thought that people exhibit all of these functions to varying degrees and at different times. It involves the differences in how people use their minds, perceive their environments, and make judgments.

Another personality assessment tool is psychogeometrics. This theory was developed Dr. Susan Dellinger in the 1980s to help corporations teach executive management about personality diversity.5 Dellinger used shapes to differentiate and understand personality types. The 5 geometric shapes are box, triangle, circle, squiggle, and rectangle. Each shape has a list of characteristics that fit a specific personality type. These shapes are used to help students understand different patient personality types. For example, a box personality type would like details and order. A triangle likes to cut to the bottom line and is bored with details. A circle would like to discuss feelings and what is going on in others' lives. Squiggles are full of energy and spontaneity yet lack order and closure. Boxes and triangles are considered linear thinkers while circles and squiggles are nonlinear thinkers. These distinct differences can be found in the personality makeup of pharmacy patients.

Exercise in Transactional Analysis

An exercise in transactional analysis was conducted to encourage students to consider the personality of the patient when preparing a counseling strategy. For students to understand this concept, they were asked to listen for parent, child, and adult phrases for 1 week while conversing with others. They were asked to reflect on and report their findings as to what ego states were used and how it made them feel. Names were not used to protect anonymity. Specifically they were asked to answer the following questions:

(1) In what ego state do you send messages?

(2) In what ego state do you respond to messages?

(3) How often do you start a sentence with “You need” or “You should?” To whom are you speaking when you use one of these phrases?

(4) In what ego states do others send messages to you? How does each ego state make you feel?

Personality Assessment

Two methods of personality assessment were demonstrated in this course, Myers-Briggs Type Indicator and psychogeometrics. Before these were presented the following concepts were discussed: problem solving, cognitive dissonance, perception, learning, self-concept and self-image, attitude, and personality. After these concepts were defined and discussed, as they relate to patient counseling, personality assessment was introduced. First, MBTI was presented with the following functions:

extrovert vs. introvert (outer world vs. inner world)

sensing vs. intuition (perception of the world around us)

thinking vs. feeling (judging the world around us)

perceiving vs. judging (dealing with the world around us)

The actual MBTI instrument was not utilized in this class. Instead, the underlying theories and definitions were presented to students as an example of a personality assessment tool. The objective of this exercise was to give students a more in depth analysis of the diversity of their patients from a psychological dimension. As each item was defined, students recorded which word from each pair best described their personality type.

After completion of the type indicator exercise, the second personality assessment tool, psychogeometrics, was presented. As each shape was discussed students determined through self-assessment what their primary shape was. How patients in each shape category required different counseling techniques was also discussed. Students were asked to choose between box, triangle, circle, and squiggle. Rectangle, which is used to describe someone in transition, was not used because as students they were all considered to be in transition. With practice, students learned to use reflective psychogeometrics to better communicate with others and hopefully in the future with patients. Students were asked to practice reflective psychogeometrics to distinguish types of personalities and to respond based on personality types. Students were asked to practice their techniques with family and friends. They were discouraged from labeling persons and were encouraged to use psychogeometrics to communicate and motivate others based on their personality preferences. For example, if a person was a circle, they would talk about feelings or relationships. If a person was a box, they would talk about a list of things to do. Students discussed how they would apply personality types to patient counseling interactions. Different strategies were discussed for counseling different personality types. A box patient would like to know the history of the medication and any details about how the medication works. Information would have to be presented in a logical order. A triangle patient would like a brief session with only the most important points included. Critical information would have to be delivered first with little or no “small talk.” Circle patients would respond better starting with “small talk” and conversations about how they are feeling and how the medication is affecting their lives and those they love. Circles would be turned off by “strictly business” interactions with their pharmacists. Squiggle patients would require follow-up calls, written instructions, and closer monitoring. Medication therapy compliance may be more difficult to achieve with these patients.

ASSESSMENT

Students were asked to practice the techniques of transactional analysis and personality assessment to gain a better understanding of communication styles and personality preferences. For TA, only qualitative data were collected from the list of questions students were given in class. Some students chose to share their experiences in class while others chose to e-mail their responses to the professor.

Students were asked to apply TA and personality assessment in their personal and professional relationships and to report their experiences. They were also asked to conduct a personality self-assessment to better understand the nature of messages they send to others. The interactive class format provided students with an opportunity to share and to discuss their experiences.

This exercise generated lively class discussion when students reported their findings. Students discovered that they used parent ego phrases because they were replaying what they have heard from their own parents and professors. For example, one female pharmacy student shared with the class that she started most sentences with her fiancé with “You need” or “You should.” When she realized this, she started sending adult messages instead of parent messages. She happily reported that this simple change had significantly improved conversation with her fiancé. He even asked her why she was being so nice and not telling him what to do all the time.

For other students one of the most common experiences was interactions with parents. Students reported conversations with their parents as being between parent and child ego states. They discovered through TA that if they sent adult messages that their parents were more likely to reply as adults. If they sent child messages, their parents would respond as parents. Students related a common frustration with parents not treating them as adults as they grew older and were now in professional pharmacy school. So, they tried sending adult messages and reported positive results with this technique. Students also reported other experiences with friends, siblings, peers, and employers.

Other common experiences were with fellow pharmacy students. Several of the student leaders discussed how they were conducting organizational meetings. They realized that they were talking to their peers in the parent ego state. Problems had developed with peers resenting being told what to do. They implemented the adult ego state and reported positive outcomes. They avoided parent messages by avoiding “you need” and “you should” phrases. They considered personality differences and which students would make better committee chairs and which would be better with detail-oriented projects.

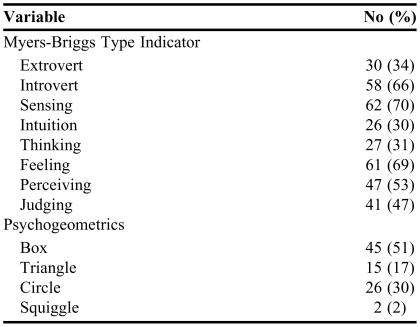

For personality assessment, descriptive data were collected and are included as Table 1. Sixty-six percent of the 88 professional pharmacy students enrolled in the fall 2006 class reported being introverts with inner-world focus, meaning that they tend to be careful with details but may have problems communicating. Seventy percent used senses to perceive the world around them meaning that they have a high dependency on what they can see, touch, and hear to process and interpret information. It also means that they prefer standards and established ways of doing things. Almost 70% judge the world by feeling instead of thinking, meaning that they are aware of the feelings of others and tend to be sympathetic instead of thinkers who are relatively unemotional and uninterested in the feelings of others. Finally, their way of dealing with the world was more evenly divided: 53% described themselves as perceiving while 47% considered themselves more judging. Perceiving was defined as being more open-minded and adapting to changing situations. Judging was defined as planning work and following the plan, completing tasks and responsibilities, and disliking interruptions.

Table 1.

Results of Personality Self-Assessment by Third-Year Professional PharmD Students Using the Myers-Briggs Type Indicator and Psychogeometrics (N=88)

DISCUSSION

These results are consistent with a 10-year analysis of Drake pharmacy students except for the category of judging. The Drake study found that students pursuing a PharmD degree were more likely to be introvert, sensing, feeling, judging than students pursuing a BS pharmacy degree. Also, female students were more likely to be feeling and judging.7

The results of the psychogeometrics exercise indicated that 51% of the students considered themselves boxes, meaning that they were detail-oriented linear thinkers who liked organization and closure. Seventeen percent chose triangle meaning that they were linear thinkers who also like being leaders. Linear thinkers are quick decision makers, strategic planners, and like to go straight to the bottom line. The circle personality shape was chosen by 30% of the students, more nonlinear thinkers. Nonlinear thinkers are more “people persons” with great communication skills. They make great listeners and team players. The last shape, the squiggle, was selected by 2 students in the class. This personality type is high energy and hates routine and following rules. Follow-up and closure are not personality traits for squiggles. Both students confessed that pharmacy school is a real challenge for them.

SUMMARY

Addressing the issue of patient communication is key to better outcomes in pharmaceutical care. To help students develop better communication skills, the concepts of transactional analysis and personality assessment were added to a Patient Counseling and Communications course. The goal was to increase students' awareness of TA and personalities as key communication tools for patient counseling.

Effective communications with patients begins with an assessment of motivational cues to understand the nature of behavior through psychological aspects. Counseling techniques can be linked with specific patient personality types. Understanding that not all patients respond the same due to cultural differences and personality traits improves students' tolerance for these differences. With this in mind, students employ techniques to motivate patients to take responsibility for their health and to comply with medication regimens.

REFERENCES

- 1.Beardsley RS. Communication skills development in colleges of pharmacy. Am J Pharm Educ. 2001;65:307–14. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tindall WN, Beardsley RS, Kimberlin CL. Communication Skills in Pharmacy Practice. 4th ed. Philadelphia, Pa: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2003. p. 122. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stewart I, Joines V. TA Today: A New Introduction to Transactional Analysis. Chapel Hill, NC: Lifespace Publishing; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Myers IB, McCaulley MH, Quenk NL, Hammer AL. MBTI Manual: A guide to the development and use of the Myers Briggs type indicator. 3rd ed. Mountain View, Calif: Consulting Psychologists Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dellinger S. Psycho-geometrics. How to Use Geometric Psychology to Influence People. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lawrence LW, Rappaport HM, Feldhaus JB, Bethke A, Stevens RE. A study of the pharmacist-patient relationship: covenant or contract? J Pharm Marketing Manage. 1995;9:21–40. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shuck AA, Phillips CR. Assessing pharmacy students' learning styles and personality types: a ten-year analysis. Am J Pharm Educ. 1999;63:27–33. [Google Scholar]