Abstract

Objective:

“Rediscovered” in 1976, transhiatal esophagectomy (THE) has been applicable in most situations requiring esophageal resection and reconstruction. The objective of this study was to review the authors’ 30-year experience with THE and changing trends in its use.

Methods:

Using the authors’ prospective Esophagectomy Database, this single institution experience with THE was analyzed retrospectively.

Results:

Two thousand and seven THEs were performed—1063 (previously reported) between 1976 and 1998 (group I) and 944 from 1998 to 2006 (group II), 24% for benign disease, 76%, cancer. THE was possible in 98%. Stomach was the esophageal substitute in 97%. Comparing outcomes between group I and group II, statistically significant differences (P < 0.001) were observed in hospital mortality (4% vs. 1%); adenocarcinoma histology (69% vs. 86%); use of neoadjuvant chemoradiation (28% vs. 52%); mean blood loss (677 vs. 368 mL); anastomotic leak (14% vs. 9%); and discharge within 10 days (52% vs. 78%). Major complications remain infrequent: wound infection/dehiscence, 3%, atelectasis/pneumonia, 2%, intrathoracic hemorrhage, recurrent laryngeal nerve paralysis, chylothorax, and tracheal laceration, <1% each. Late functional results have been good or excellent in 73%. Aggressive preoperative conditioning, avoiding the ICU, improved pain management, and early ambulation reduce length of stay, with 50% in group II discharged within 1 week.

Conclusion:

THE refinements have reduced the historic morbidity and mortality of esophageal resection. This largest reported THE experience reinforces the value of consistent technique and a clinical pathway in managing these high acuity esophageal patients.

The authors’ 30-year experience with 2007 transhiatal esophagectomies (THE) for disorders of the intrathoracic esophagus is reviewed. Hospital mortality for THE was reduced to 1% and morbidity also reduced with refinements in technique and a consistent clinical pathway in managing these high acuity patients.

In 1978, the senior author reported at the Annual Meeting of the American Association for Thoracic Surgery his experience with 28 “blunt” transhiatal esophagectomies, 4 for benign disease and 22 for esophageal carcinoma.1 The concept of resecting the esophagus without performing a thoracotomy had been proposed initially in 1913 by the German anatomist, Denk, who used an instrument similar to a Mayo vein stripper to mobilize the intrathoracic esophagus.2 In 1933, the British surgeon, Turner, carried out the first successful transhiatal blunt esophagectomy for carcinoma and reestablished continuity of the alimentary tract using an antethoracic skin tube at a second operation.3 But as safe open thoracotomy became a reality with the advent of general endotracheal anesthesia, and it was possible to resect the esophagus under direct vision, transhiatal esophagectomy without thoracotomy (THE) was performed only sporadically, usually as a concomitant procedure with laryngopharyngoesophagectomy for pharyngeal or cervical esophageal carcinomas when the stomach was used to restore continuity of the alimentary tract.4–6 Kirk used this approach for palliation of incurable esophageal carcinoma in 5 patients.7 Thomas and Dedo treated 4 patients with pharyngoesophageal caustic strictures by blunt thoracic esophagectomy without thoracotomy, mobilization of the stomach through the posterior mediastinum, and then a pharyngogastric anastomosis.8

The first transhiatal esophagectomy performed by the senior author (MBO) in 1976 was unplanned and without prior knowledge of the historical precedent for the procedure. Avoidance of (1) combined thoracic and abdominal incisions in debilitated patients with esophageal obstruction and (2) a mediastinal anastomosis with its potential for mediastinitis from a leak formed the basis for advocating this approach. This newly “resurrected” operation was not initially well received, and critics of transhiatal esophagectomy were quick to point out that the operation violated basic surgical principles of adequate hemostasis and exposure and was an inadequate “cancer operation” because it precluded an en bloc mediastinal lymph node dissection. Following our 1978 publication, multiple reports of series of transhiatal esophagectomies amply addressed the initial criticism of transhiatal esophagectomy. The 1999 report of the University of Michigan Section of Thoracic Surgery’s 22 year experience with 1085 transhiatal esophagectomies provided a benchmark standard for the operation.9

Since 2000, mortality after esophageal resection has been shown to be strongly related to the hospital volume of the procedure.10–13 In the subsequent 8.5 years since our 1999 report, an additional 944 of these operations have been performed for diseases of the intrathoracic esophagus bringing our experience with transhiatal esophagectomy to more than 2000. This experience of a high volume esophageal surgery center has resulted in a progressive reduction in the historic morbidity and mortality of esophageal resection. The changing trends and lessons learned in this cumulative experience are the subject of this report.

METHODS

Between 1976 and December 2006, THE has been performed by the University of Michigan General Thoracic Surgery Service in a total of 2109 patients. Patients with hypopharyngeal, postcricoid, cervicothoracic, and thyroid malignancies, (66) as well as patients operated upon by the Thoracic Surgery service at the Ann Arbor Veterans Administration Hospital (36) are excluded from consideration in this report, therefore there may be variation in these data presented for group I (below) and our previously published report.9 One thousand and sixty-three patients with diseases of the intrathoracic esophagus operated upon between 1976 and June 1998—previously reported9 —constitute group I, and 944 operated upon between July 1998 and December 2006, group II. The cumulative results have been analyzed retrospectively using our esophageal resection database and follow up through personal interviews and examinations, written correspondence with patients, their families and physicians. Permission for this retrospective review was obtained from the University of Michigan Institutional Review Board with waiver of informed consent.

Statistical Analysis

Difference in disease prevalence, patient and tumor characteristics between time periods 1976 to 1998 and 1998 to 2006 were analyzed by Pearson’s χ2 test and by the Wilcoxon signed-rank test. To assess change over time, the Mantel-Haenszel statistic was used for nominal variables and the Spearman rank correlation coefficient was used for continuous variables. To assess changes over time in a multivariate manner, a linear logistic regression model was used, with year of surgery as a covariate. A significantly non-zero slope in the time covariate indicated a time trend. The time trend plots were depicted using fitted values from the logistic model.

Overall survival after THE for cancer was estimated using the Kaplan-Meier analysis, and the log-rank test was used to assess the homogeneity of the estimates across the strata of interest. The median survival time, along with 95% CI, was also presented. Cox proportional hazards models were fit to assess the time trend of survival probability, while adjusting for significant patient and tumor characteristics found in the univariate time trend analysis. Cox modeling was also used to explore the prognostic effect of clinical and pathologic variables. Subjects surviving beyond 5 years after surgery were censored. All statistical analyses were done using SAS v9.0 (Carey, NC). A 2-tailed P value of 0.05 or less is considered to be statistically significant.

Patient Demographics

Of the 2007 total patients, 482 (24%) had benign disease and 1525 (76%) malignancy. (Table 1) Among the patients with benign disease, there was a decrease in the number of esophagectomies performed for strictures, from 27% in group I to 10% in group II, whereas the number of esophagectomies for Barrett’s mucosa with high grade dysplasia increased from 19% in group I to 44% in group II. The difference between the 2 groups in distribution of diagnoses was significant (P < 0.0001). The age of patients undergoing operation for benign indications, but not cancer, increased significantly over time (P < 0.0001). There is a small but significant increase in male cases over time for both benign (P < 0.0001) and cancer (P < 0.01). Esophagectomies for benign disease tending to be nearly equally divided between men and women, whereas 80% of the esophagectomies for carcinoma were performed in men, and only 20% in women. The mean ages of patients in both groups were similar, 61 and 62 years. In group I, 235 patients (22%) were 71 years of age or older; 45 (4%) were 80 years of age or older. In group II, 241 (26%) were 71 years of age or older; 56 (4%) were 80 years or older.

TABLE 1. Indications for Transhiatal Esophagectomy (2007 Patients)

Among the patients with carcinoma, esophagectomies for squamous cell carcinoma have decreased from 27% in group I to 13% in group II, whereas resections for adenocarcinoma have increased from 72% to 86% (P < 0.0001). In group I patients with malignant disease, 562 (72%) had esophageal adenocarcinomas (5 upper third, 52 middle third, and 505 lower third or cardia), and 208 (27%) had squamous cell carcinomas (28 upper, 108 middle, and 72 lower third). One percent had a variety of less common esophageal malignancies, including adenosquamous, anaplastic, small cell, undifferentiated, and follicular carcinomas, stromal malignancy, and carcinosarcoma. In group II, 640 (86%) of the malignancies were adenocarcinomas (3 upper, 28 middle third, and 609 lower third or cardia), and 95 (13%) had squamous cell carcinoma. Five patients (<1%) had less common esophageal malignancies, including adenosquamous carcinoma, lymphoma, poorly differentiated and neuroendocrine carcinoma). The proportion of adenocarcinoma cases has significantly (P < 0.0001) increased over time.

Of 2029 total patients undergoing a THE from 1976 to 2006 for diseases of the intrathoracic esophagus, conversion to a transthoracic approach was required in 22 (<2%), in 13 because of fixation of the esophagus to mediastinal tissues that prevented a safe THE, in 9 to control mediastinal bleeding (4 died of uncontrollable hemorrhage), and in 4 to repair a tracheobronchial tear. Throughout the nearly 30 years we have performed THE, the operation has generally been possible despite potential increased periesophageal mediastinal inflammation from prior operations, perforations, or radiation therapy. Of the 1525 patients with cancer, 627 (41%) have had a history of mediastinal radiation within weeks to 23 months of the operation. Of the 482 patients with benign disease, 227 (47%) have undergone 1 or more prior esophageal or periesophageal operations: hiatal hernia/antireflux repairs, (189) esophagomyotomy (91); vagotomy for peptic ulcer disease, (17) including 15 with pyloroplasty or pyloromyotomy and 2 with gastric resections; repair of perforation (10); and a variety of others (29).

Esophageal resection and reconstruction were performed at the same operation in all but 13 patients, 4 of whom died intraoperatively of uncontrollable hemorrhage. (Table 2) Nine patients underwent a THE, cervical esophagostomy and feeding jejunostomy. Four with benign disease had a delayed reconstruction with colon 2 to 8 weeks later. In 5 patients, 3 with extensive cancers and 2 with benign disease, no reconstruction was ever performed. In the remaining 1994 patients, esophageal resection and reconstruction were performed at the same operation. The stomach was used as the esophageal substitute in 1942 (97%) of these patients. Colon was used in 52 (3%), whose prior caustic gastric injuries or previous gastric operations precluded a cervical esophagogastric anastomosis. The esophageal replacement was positioned in the posterior mediastinum in the original esophageal bed in all but 23 patients with either residual posterior mediastinal tumor or fibrosis and narrowing, which prevented a tension-free, unrestricted placement of the conduit. In these later patients, the retrosternal route was used. In 94 (9%) patients in group I and 27 (3%) in group II, a partial upper sternal split in addition to the standard left neck incision was performed to gain access to the cervicothoracic esophagus either because of a “bull neck” habitus or inability to extend the neck due to cervical osteoarthritis. Accessible subcarinal, paraesophageal, gastrohepatic ligament, and celiac axis lymph nodes were routinely sampled in patients with esophageal carcinoma, but an en bloc wide resection of the esophagus and adjacent regional lymph nodes was not performed. After removal of the esophagus from the posterior mediastinum, the hiatus was retracted widely and an inspection carried out for untoward bleeding and possible pleural entry. Nearly 75% of all patients undergoing THE required either a single or bilateral chest tubes. In patients undergoing esophageal replacement with stomach, a pyloromyotomy was routine, and in every patient undergoing a THE, a 14 French feeding jejunostomy tube was placed.

TABLE 2. Esophageal Reconstruction After Transhiatal Esophagectomy (2007 Patients)

Postsurgical pathologic TNM staging of the resected carcinomas is shown in Table 3. Neoadjuvant chemoradiation was used in 28% of group I patients and 52% group II patients. Among the 156 patients with Stage 0 tumors, 31 (20%) had carcinoma in situ (Tis), while 125 (80%) had no residual tumor after preoperative radiation and chemotherapy. There is a significant decrease in advanced postsurgical pathologic TNM stages over time, which may be associated with the significant increase in neoadjuvant chemoradiation (both P < 0.0001).

TABLE 3. Pathologic TNM Staging of Intrathoracic Esophageal Carcinomas After Transhiatal Esophagectomy

RESULTS

There were 4 intraoperative deaths from uncontrollable hemorrhage that occurred during transhiatal mobilization of the esophagus (Table 4). Eight additional patients, experienced inordinate intraoperative bleeding (>4000 mL), 4 intramediastinal due to a torn azygos vein (3) or a large prevertebral collateral vein (1); 3 intraabdominal due to portal hypertension from cirrhosis (2) or splenic injury (1); and 1 from laceration of the right ventricle during chest tube insertion. With greater experience and attention to mediastinal hemostasis achievable through the diaphragmatic hiatus, average intraoperative blood loss has fallen from a median of 510 mL in group I to 300 mL in group II (P < 0.0001).

TABLE 4. Intraoperative Blood Loss With Transhiatal Esophagectomy

Intraoperative Complications

A thoracotomy to control mediastinal bleeding during transhiatal mobilization of the esophagus was performed in 9 patients (<1%) and was successful in 5. A splenectomy was required because of intraoperative injury in 48 patients (2%). There have been a total of 8 (<1%) intraoperative membranous tracheobronchial tears, 4 requiring a right thoracotomy for repair, and 4 repaired through a partial upper sternal split. Violation of gastric or duodenal mucosal integrity during performance of the pyloromyotomy occurred in 32 (<2%) and was managed by repairing the hole with interrupted 5-0 polypropylene sutures and buttressing the repair with adjacent omentum. There has been 1 postoperative pyloromyotomy leak, and only 2 patients in this entire series have experienced clinically significant early postoperative delayed gastric emptying.

Postoperative Complications

Postoperative mediastinal bleeding requiring a thoracotomy for control within 24 hours of THE occurred in 7 patients (<1%). Recurrent laryngeal nerve injury, as manifested by early postoperative hoarseness, occurred in 72 patients (7%) in group I and 19 patients (2%) in group II(P < 0.0001). This hoarseness was generally transient and due to vocal cord paresis, and resolved in 2 to 12 weeks. Of 24 patients with persistent vocal cord paralysis, 9 required cord medialization procedures. The incidence of recurrent laryngeal nerve injury after THE has been influenced by operative volume. From 1978 to 1982, with an average of 23 THE operations annually, the incidence of recurrent nerve injury was 32%; from 1983 to 1987, with an average 45 THE procedures, 5%; from 1988 to 1992, averaging 55 THE operations, 3%; and since 1993, averaging 82 to 100 THE procedures annually, the incidence of recurrent laryngeal nerve injury has been 1% to 2%.

Chylothorax has occurred in 25 (1%) of all THE patients and has been managed successfully in each case by transthoracic thoracic duct ligation within 7 to 10 days of the esophageal resection. Abdominal wound infection or dehiscence occurred in 3% of both group I and group II patients. Clinically significant pneumonia or atelectasis prolonging the hospital stay beyond 10 days occurred in 2% of both group I and group II patients.

The overall anastomotic leak rate after cervical esophagogastric anastomosis has been 12%, leaks occurring in 14% (146 patients) in group I, 25% (36) with benign disease, and 75% (110) carcinoma, and in 9% (86) of group II patients, 13% (11) with benign disease and 87% (75) with carcinoma. Since 1997, routine use of the side to side stapled cervical esophagogastric anastomosis as described by the senior author (MBO)14 has resulted in a noticeable decrease in the leak rate and need for postoperative anastomotic dilatations. Among the 1898 hospital survivors of THE in whom the stomach was positioned in the posterior mediastinum in the original esophageal bed, there were 211 anastomotic leaks (11%) compared with 7 leaks (70%) in the 10 patients with retrosternal placement of the stomach. Of the total 232 cervical esophagogastric anastomotic leaks in this series, all but 15 were managed successfully in the short term by opening the neck wound at the bedside and local wound packing until healing by secondary intent occurred. Of the 185 patients with carcinoma who had anastomotic leaks after their THE and cervical esophagogastric anastomosis, 81 (44%) had undergone neoadjuvant chemoradiation therapy, which may have jeopardized healing of the anastomosis by affecting the upper stomach. Gastric tip necrosis necessitating takedown of the intrathoracic stomach and a cervical esophagostomy has occurred in 15 patients (2%), 13 with carcinoma and 2 with benign disease.

Mortality

Among these 2007 patients undergoing a THE, the hospital mortality rate for group I patients was 4% and for group II, 1%, for an overall hospital mortality of 3%. Forty-two (3%) of the deaths occurred among the 1525 patients with carcinoma, and 9 (2%) among the 482 with benign disease. The causes of death were hepatic failure, respiratory insufficiency, myocardial infarction, intraoperative hemorrhage, pneumonia, sepsis, intestinal ischemia, sudden death/cardiac arrest, pulmonary embolus, posterior mediastinal abscess, retroperitoneal abscess, unrecognized brain metastasis, delayed pyloromyotomy leak, portal vein thrombosis, and a cyclosporine-related neurologic catastrophe.

The hospital mortality rate has steadily fallen as the volume of THE operations has increased, averaging 10% from 1978 to 1982 with an average of 23 THE operations annually; 5% from 1983 to 1987 with an average of 45 THE operations; 2% from 1988 to 1992, with an average number of 55 THE operations; 3% from 1993 to 1997, with an average number of 82 THE operations; and since 1998, 1%, with more than 100 THE operations annually.

Length of Stay

The median length of hospitalization for 736 hospital survivors of THE and a cervical esophagogastric anastomosis for carcinoma in group I was 10 days, and for those with benign disease 11 days. Overall, 52% of group I patients were discharged within 10 days of THE, 28% within 2 weeks, and 20% after 2 weeks.

For the most part, group I patients underwent their THE when it was our policy to continue an otherwise uncomplicated hospitalization until postoperative day 10, when presumably the risk of anastomotic leak had passed. Since approximately 1996, however, patients doing well after THE have a barium swallow examination to insure anastomotic healing and may be discharged as early as postoperative day 7. The median length of hospitalization for the 718 hospital survivors of THE and a cervical esophagogastric anastomosis for carcinoma in group II was 8 days and for those with benign disease, 8 days. Overall, 50% of group II patients were discharged within 7 days, 38% within 2 weeks, and 12% after 2 weeks.

Functional Results

Of the 56 patients in this entire series who underwent a THE and esophageal replacement with colon, 18 of the 27 with cancer died within an average of 24 months. Of the 29 patients with benign disease, there were only 19 evaluable patients. Due to the small number of surviving patients with colon interpositions available for follow-up, they are excluded from this assessment of functional results.

Esophageal Substitution With Stomach for Benign Disease

Because of their longer life expectancy compared with patients with cancer, patients undergoing esophageal resection and reconstruction for benign disease provide a better indicator of the functional results of visceral substitution. Among the 444 hospital survivors of THE and a cervical esophagogastric anastomosis for benign disease, follow-up information regarding functional results was available for up to 311 months (median 41 months) after the operation for 403. Our database tracks the following functional results: presence and degree of dysphagia, regurgitation, and postvagotomy diarrhea and cramping (“dumping”).

In patients who experience a cervical esophageal anastomotic leak, it has been our policy to initiate esophageal bougienage by passage of 36, 40, and 46 French Maloney esophageal dilators at the bedside within 7 to 10 days of the occurrence of the leak to minimize late stenosis. All THE patients are instructed at the time of discharge to return to our clinic for an outpatient cervical esophagogastric anastomotic dilatation with a 46 French or larger Maloney bougie if they experience any degree of cervical dysphagia. In patients who have experienced a leak, passage of a 46 French dilator within 1 month of discharge is routine. With this liberal use of esophageal dilatation therapy, (55%) of these patients with benign disease have had at least 1 postoperative anastomotic dilatation. At the time of their latest follow-up, however, 268 of the 412 responding patients (65%) were eating a regular unrestricted diet with no dysphagia, 61 (15%) had occasional mild dysphagia requiring no treatment, 76 (18%) have required an occasional dilatation but swallow well between treatments and were satisfied with their ability to eat, and 7 (2%) had “severe” dysphagia requiring regular dilatations (weekly or monthly). The majority of these patients with dysphagia are able to swallow 46 French or larger esophageal bougies.

In assessing the presence of regurgitation, 217 (53%) denied having any regurgitation of gastric contents whatsoever. One hundred and fifty-three (38%) had occasional, mild regurgitation only if reclining or in the prone position shortly after eating; this was a minor problem, which required no treatment. Thirty-seven (9%) were sleeping with their head elevated at night (multiple pillows, a wedge, or sleeping in a recliner) because of more troublesome nocturnal regurgitation. One patient (<1%) had experienced pulmonary complications caused by aspiration.

With regard to dumping, at last follow-up, 247 patients (67%) had no postprandial cramping or diarrhea. One hundred and forty-four patients (33%) had experienced varying degrees of dumping syndrome (postprandial nausea, cramping, diaphoresis, or diarrhea; these symptoms typically dissipated over time and were usually controlled with diphenoxylate or Imodium and supplemental fiber in the diet for diarrhea and levsin for “vagal” nausea and diaphoresis after eating. One hundred and twelve (28%) had “mild” diarrhea, infrequent and requiring no treatment; 35 (9%), had “moderate” diarrhea occasionally requiring medication, and 10 (3%) “severe” postprandial diarrhea requiring ongoing medication. Mild postprandial cramping requiring no treatment was reported by 107 patients (29%) and moderate cramping requiring occasional use of antispasmodics by 17 (5%).

Overall functional results (assessment of dysphagia, regurgitation and dumping available) based upon the most recent follow-up evaluation were scored as excellent (completely asymptomatic) in 98 (24%), good (mild symptoms requiring no treatment) in 168 (42%), fair (symptoms requiring occasional treatment, either dilatations or antidumping medication) in 119 (30%), and poor (symptoms requiring ongoing treatment) in 18 (4%).

Esophageal Substitution With Stomach for Carcinoma

Among the 1454 hospital survivors of THE and a cervical esophagogastric anastomosis for carcinoma, follow-up information regarding functional results for up to 98 months (median 61 months) after THE was available for 1048. As for the patients with benign disease, esophageal dilatation was used liberally for any postoperative complaint of dysphagia. At latest follow-up, 746 (52%) have never undergone a postoperative anastomotic dilatation. Three patients have required resection of a severe anastomotic stricture and construction of a new cervical esophagogastric anastomosis. At last follow-up, 863 (76%) had no dysphagia whatsoever, 107 (10%) had occasional mild dysphagia requiring no treatment, 118 (11%) had moderate dysphagia requiring an occasional dilatation, and 30 (3%) had severe dysphagia requiring ongoing dilatations.

Eight hundred and twenty (75%) denied having any regurgitation; 236 (22%) had occasional mild regurgitation if recumbent after a large meal but generally sleep horizontal at night with their head elevated on 1 or 2 pillows; and 32 (3%) had sufficient nocturnal regurgitation to require them to sleep upright at night. One (<1%) has had pulmonary complications of aspiration.

At latest follow-up, 814 (75%) deny any postprandial cramping or diarrhea. Four hundred and eighty-seven (34%) had varying degrees of dumping syndrome. Seven hundred and ninety (76%) had no diarrhea. One hundred and eighty-nine (18%) had mild diarrhea requiring no treatment, 47 (5%) had moderate diarrhea requiring medication intermittently, and 9 (1%) had severe diarrhea requiring ongoing medication. Cramping postprandial pain was mild, requiring no treatment in 169 patients (17%), or moderate, requiring antispasmodics intermittently in 17 (2%).

Overall functional results (assessment of dysphagia, regurgitation, and dumping available) in the carcinoma patients were excellent (asymptomatic) in 522 (50%), good (mild symptoms requiring no treatment) in 316 (30%), fair (symptoms requiring occasional treatment) in 175 (17%), and poor (symptoms requiring ongoing treatment) in 35 (3%).

Patient Satisfaction

For the past 14 years, postoperative patient satisfaction has been measured by asking 3 questions at the time of follow-up: “Are you generally pleased with your ability to eat?,” “Are you better than you were before your operation?,” and “Knowing what you know now about the procedure, would you have the operation again (if faced with the same circumstances)?” At the time of their last follow-up visit, 89% of patients with both cancer and benign disease have responded that they are generally pleased with their ability to eat, 87% that they are better than before the operation, and 96% that they would have the operation again if faced with the same decision.

Survival of Patients With Carcinoma

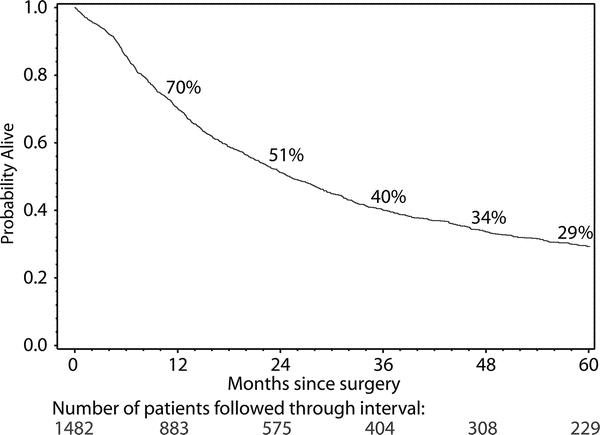

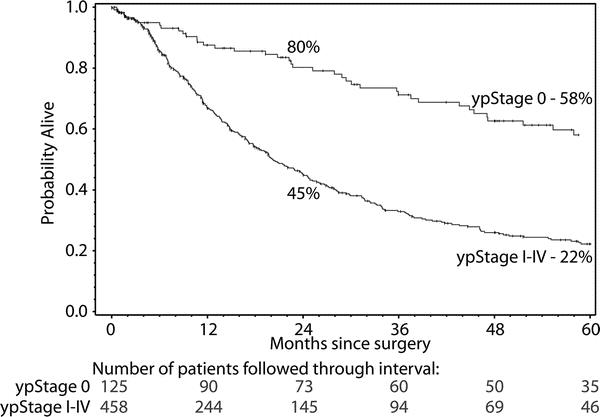

Of the 1525 patients undergoing THE for carcinoma, 1483 left the hospital alive. No follow-up was available on 8 patients (0.5%). Patients were followed for up to 311 months after THE (median follow up 59.4 months). The Kaplan-Meier actuarial survival after THE for carcinoma of the intrathoracic esophagus and cardia in these patients is shown in Figure 1. Survival by tumor site is shown in Figure 2. There are significant (P < 0.0001) differences in survival, patients with mid esophageal tumors having the worst prognosis. The survival of patients who received chemotherapy and radiation therapy before THE is shown in Figure 3. As is the case for patients undergoing a transthoracic esophagectomy (TTE), the stage of the resected tumor was an important determinant of survival after THE: those with stage 0 or I tumors lived considerably longer than those with more advanced disease (P < 0.0001) (Fig. 4, Table 5). The survival rate after THE for adenocarcinoma was better than after THE for squamous carcinoma. There was an overall statistically significant (P < 0.0001)) survival advantage for adenocarcinoma, and this advantage was evident through 5 years after surgery. (Fig. 5)

FIGURE 1. Kaplan-Meier actuarial survival curve of 1482 patients undergoing transhiatal esophagectomy for carcinoma of the intrathoracic esophagus and cardia.

FIGURE 2. Site-dependent Kaplan-Meier survival curves in patients undergoing transhiatal esophagectomy for carcinoma of the intrathoracic esophagus and cardia. Differences in survival were statistically significant (P < 0.0001).

FIGURE 3. Kaplan-Meier survival curves in 583 patients who received chemotherapy and radiation therapy before THE. One hundred and twenty-five (21%) were “complete responders” (T0N0 tumors) whose survival was considerably better than those with residual carcinoma in the resected specimen. Differences in survival were statistically significant (P < 0.0001).

FIGURE 4. Stage-dependent Kaplan-Meier actuarial survival curves in patients undergoing transhiatal esophagectomy for carcinoma of the intrathoracic esophagus and cardia.

TABLE 5. Kaplan-Meier Survival After Transhiatal Esophagectomy by Tumor Stage

FIGURE 5. Histology-dependent Kaplan-Meier survival curves in patients undergoing transhiatal esophagectomy for carcinoma of the intrathoracic esophagus and cardia. Differences in survival were statistically significant (P < 0.0001).

In summary, we observed significant increases in the proportion of adenocarcinoma, lower/cardia tumors, earlier post surgical TNM stages, and the use of preoperative chemoradiation therapy. In a multivariate analysis using the Cox proportional hazard model, the overall survival significantly increased over time (P < 0.0001) after taking into account patient characteristics such as age, gender, smoking, and alcohol usage, and prognostic factors mentioned above. In the Cox model, all significant prognostic factors in the univariate analysis maintained their prognostic value. Gender and alcohol usage were not of prognostic value in the Cox model.

DISCUSSION

In the past 30 years, THE has become an accepted operation that has substantially reduced the morbidity and mortality associated with traditional transthoracic esophageal resection. A 2001 meta-analysis of 7527 patients undergoing either THE or TTE for carcinoma between 1990 and 1999 documented statistically significant differences favoring THE over TTE in hospital mortality, blood loss, pulmonary complications, chylothorax, ICU stay, and hospital stay, but TTE patients had lower anastomotic leak rates than THE patients and a lower incidence of vocal cord paralysis.15

Recently, mortality after esophageal resection has been linked to hospital volume.10–13 The National Cancer Policy Board has recommended that hospital volume should be a quality indicator for esophageal resection.16 The Leapfrog group, a coalition of businesses with large numbers of employees and other payers, has recommended that patients requiring an esophagectomy be selectively referred to high-volume hospitals.17 But the experience of the individual surgeon, not only hospital volume, is a major determinant of operative mortality. Interestingly, definitions of both hospital and surgeon volume which are associated with demonstrable differences in hospital mortality after esophagectomy seem inordinately low. Dimick and associates have reported significant differences in risk-adjusted mortality between high-volume (more than 12 esophagectomies per year) and low-volume (less than 5 esophagectomies per year) hospitals (24.3% vs. 11.4%; P < 0.001) and high-volume (more than 5 esophagectomies per year) and low-volume (less than 2 esophagectomies per year) surgeons (20.7% vs. 10–7%; P < 0.001).18

An esophagectomy, whether for benign or malignant disease, is seldom an emergency, and an important lesson learned in esophagectomy patients operated upon in recent years has been to delay the operation until the patient is optimally prepared. We insist upon complete abstinence from cigarette smoking for a minimum of 3 weeks before operation and emphasize regular preoperative use of an incentive inspirometer and walking 1 to 3 miles a day depending upon age and physical condition to prepare the patient for early postoperative ambulation. Use of epidural anesthesia in our THE patients, despite its drawbacks, has provided sufficiently comfortable postoperative breathing that they are typically extubated in the operating room, and postoperative mechanical ventilation and an intensive care unit stay are seldom required. Whereas in group I patients, postoperative intensive care was routine, in our 943 group II THE operative survivors, only 37 (4%) have required an intensive care unit stay early after their operation. A series of >2000 THE patients with only 2% having postoperative atelectasis or pneumonia of sufficient severity to prolong their hospitalization beyond 10 days is a testimony to better preoperative physical conditioning, and with aggressive early postoperative ambulation and use of the incentive inspirometer begun preoperatively, the length of hospitalization after esophagectomy is often 1 week.

The incidence of recurrent laryngeal nerve injury associated with THE has been reduced to 1% to 2% with greater experience with cervical esophageal mobilization and compulsive avoidance of placement of any metal retractor or instrument against the tracheoesophageal grove; only a finger should be used to retract the thyroid and trachea medially. Although vocal cord paresis often resolves within 6 months, particularly in the elderly and those with more severe COPD, experiencing aspiration, a temporary Gelfoam vocal cord medialization procedure maybe life-saving.

One of the most striking recent trends in treating esophageal carcinoma has been the dramatic rise in the incidence of adenocarcinoma. The current epidemic of obesity in the United States has been associated with a rise in the prevalence of hiatal hernia, GERD, Barrett’s metaplasia, and esophageal adenocarcinoma, the latter by 350% between 1976 and 1994.19–22 Eight-six per cent of group II carcinomas were adenocarcinomas compared with 72% of group I patients (P < 0.0001). The increasing BMI of patients undergoing THE for both Barrett’s mucosa with high grade dysplasia and Barrett’s adenocarcinoma poses unique challenges for the operating surgeon. We have found that exposure of the gastroesophageal junction and transhiatal esophageal mobilization in profoundly obese patients are facilitated by the Buchwalter table-mounted retractor with deep liver-retracting blades, special-order long (15–17 inches) right angle clamps, and long (16 inches) electrocautery extensions. In our experience as a high-volume esophageal surgery center, the outcomes of THE and a cervical esophagogastric anastomosis in profoundly obese patients can be comparable to those in nonobese patients.23

Several technical “lessons” bear emphasis. Minimizing gastric trauma is key to minimizing the incidence of cervical esophagogastric anastomotic leak. The dictum “pink in the abdomen [after complete gastric mobilization] and pink in the neck [after transposing the stomach through the posterior mediastinum and delivering the fundus into the cervical wound]” is a current guiding principle.24 No traction drains, sutures, or bags are affixed to the mobilized stomach, which is manually manipulated upward through the hiatus and mediastinum. Before transposing the mobilized stomach, the hand and forearm should be advanced upward through the posterior mediastinum until 3 fingers emerge from the cervical wound to be certain that there are no undivided vagal or fibrous mediastinal bands to impinge upon the stomach and that there is an ample mediastinal tunnel to accommodate the stomach. A pyloromyotomy to insure adequate gastric emptying after the vagotomy which accompanies a THE is routine. The cervical esophagus begins at the upper esophageal (cricopharyngeal) sphincter at the level of the cricoid cartilage; extending the cervical incision and dissecting above this point provides no improved access to the cervical esophagus. If the cricoid cartilage is in close proximity to the sternal notch (as in a patient with a “bull-neck” habitus or an elderly patient who cannot extend the neck due to cervical osteoarthritis), the length of cervical esophagus available for construction of a cervical esophagogastric anastomosis is minimal. In such cases, addition of a partial upper sternal split may provide much needed exposure of the esophagus in the superior mediastinum.25 Use of a side-to-side stapled cervical esophagogastric anastomosis has reduced the incidence of anastomotic leak and subsequent stricture formation.14 Surgeon experience influences the anastomotic leak rate as well. The senior author’s (MBO) cervical esophagogastric anastomotic leak rate is 3% versus our overall 9% leak rate using the stapled anastomosis. Management of the cervical esophagogastric anastomotic leak is a topic unto itself and will be the subject of a future report. We have learned, however, that early bedside esophageal anastomotic dilatation (with 36, 40, and 46 French dilators) within 1 week of opening and draining the neck wound has a very positive effect on closure of the fistula by insuring preferential flow of swallowed esophageal contents down the true lumen rather than out the leak. Maloney tapered bougies, not balloon dilators, are most effective in managing cervical esophageal anastomotic leaks and should be part of the esophageal surgeon’s armamentarium. After discharge from the hospital an aggressive follow-up dilatation program in the first few months after THE, including instruction in self-dilatation, if necessary, is important to prevention of severe late stenosis and providing comfortable swallowing.

Although controversy exists about the use of induction chemotherapy and concurrent radiation in patients undergoing an esophagectomy for carcinoma, the current enthusiasm for this approach is increasingly supported by reports of downstaging large tumors and making them more resectable, and improved survival, particularly in patients who are complete responders to this treatment.26,27 Although only one randomized, prospective trial has demonstrated a benefit,28 a recent meta-analysis lends further credence to the survival advantage provided by neoadjuvant therapy for esophageal cancer.29 In this analysis comparing neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy and surgery versus surgery alone in over 1200 patients, the hazard ratio for overall mortality among patients receiving neoadjuvant treatment was 0.81 (95% CI 0.70–0.93; P = 0.002). In our experience, among 583 patients who received neoadjuvant chemoradiation, 125 (21%) were complete responders (T0N0 tumors) who had a 2 year survival of 80% and a 5 year survival of 58% (Fig. 3). We continue to support the routine use of neoadjuvant chemoradiation for stage II, III, and selected IVa esophageal carcinomas in patients younger than 75 years of age with an adequate performance status.

At a truly high-volume esophageal surgery center such as the University of Michigan performing an average 120 transhiatal esophagectomies annually for the past 7 years, the hospital mortality of 1% in our most recent series is testament to the improved outcomes which have followed continuous refinements in the management of these patients pre, intra- and postoperatively.

Discussions

Dr. Carlos A. Pellegrini (Seattle, Washington): Thank you for asking me to be the primary discussant of this presentation, destined to become a landmark paper and a classic in the surgical literature. Indeed, Dr. Orringer has, in a masterful way, analyzed the development and the evolution of transhiatal esophagectomy, an operation that although described by others, was brought to the forefront of the surgical armamentarium and became a practical alternative for patients who needed an esophagectomy by Dr. Orringer and his group. The analysis of their vast experience, the largest ever reported, shows that the safety and efficacy of an operation are dependent upon careful perioperative management, including patient selection and preoperative preparation, impeccable and carefully standardized operative technique, and attentive postoperative management including early detection and treatment of complications. When these elements are applied systematically in a center with high volume it is possible to decrease complications, sequelae and mortality the way the authors have. This is a simple yet important take-home message from this paper as I believe the principle expressed by Dr. Orringer is applicable as such to almost any field of endeavor in surgery.

I have 4 questions for you Dr. Orringer, 2 regarding malignant and 2 regarding benign disease.

With benign disease, one of the arguments for the use of the colon as an esophageal substitute instead of the stomach is the potential development of Barrett in the cervical esophagus. In this large series with up to 300 months of follow-up, how often have you examined the esophagus for the presence of Barrett and how often did it occur?

Second, you performed a transhiatal esophagectomy in over 100 patients with achalasia, presumably with end-stage disease. These esophagi are large, occupy most of the space in the mediastinum and have developed a thick wall covered by a network of large vessels. When do you recommend the esophagectomy? Would you ever recommend in these patients a re-myotomy or some other procedure rather than a resection and replacement? Are there any techniques to prevent bleeding?

Turning to the use of this technique to treat cancer, I would like for you to expand a little bit more on its Achilles’ heel: the lack of a formal lymphadenectomy. I would specifically like to hear you discuss pathologic staging without a complete lymphadenectomy and your thoughts on the claims that a more complete lymphadenectomy yields better survival.

And last but not least, you have emphasized the fact that without a thoracotomy these patients recover faster and have less sequelae. With that in mind, have you considered the potential use of laparoscopic assistance to minimize even further the operative trauma? In patients in whom we do transhiatal esophagectomy, we have found that with your technique using laparoscopic dissection of the fundus of the stomach and the lower third of the mediastinum we minimize the handling of the stomach, obtain better hemostasis in the distal mediastinum, and are able to do a better lymph node dissection of the left gastric artery and periesophageal and aortic nodes.

I take this opportunity to congratulate you on a fantastic analysis of this impressive series of patients and in particular for having developed, perfected and taught to many of us a practical way to do an esophagectomy with the lowest cost and highest yield to patients with esophageal disease.

Dr. Mark B. Orringer (Ann Arbor, Michigan): Thank you, Dr. Pellegrini, for your questions, which come with a great deal of insight from a surgeon who does this work.

Barrett’s mucosa in the cervical esophagus after transhiatal esophagectomy occurred in 1 patient of whom I am aware in our entire 30-year experience. Obviously, not every patient undergoes endoscopic follow-up after transhiatal esophagectomy. The single patient with Barrett’s mucosa in the cervical esophagus retrospectively had long segment Barrett’s extending to 23 to 24 cm from the upper incisors preoperatively, so this may represent an inadequate margin of resection rather than the new development of Barrett’s mucosa due to reflux into the cervical esophagus. I think that it is a very, very rare occurrence that the cervical esophagus will develop Barrett’s after a transhiatal esophagectomy.

Transhiatal esophagectomy for achalasia absolutely is reserved for patients with end-stage disease or for those with failed prior myotomies who historically have a poor result with repeat esophagomyotomy. The experience with achalasia in South America, which is much more vast than in this country, has taught that when the esophagus reaches the mega-esophagus stage, 6 to 8 cm size or larger, and particularly when the esophagus develops a sigmoid configuration that interferes with emptying even after a complete myotomy, an esophagectomy is the best option. So for patients with an enlarged esophagus that still has a straight axis, a myotomy is our procedure of choice. But for those with a mega-esophagus, a sigmoid configuration, or recurrent symptoms after a prior esophagomyotomy, we advise an esophagectomy. And you are correct; there are some unique technical aspects to performing a transhiatal esophagectomy for achalasia. The mega-esophagus typically veers to the right, and one must realize that intraoperative dissection in the right chest is necessary. One must pay particular attention to obtaining hemostasis in the mediastinum and performing the dissection under as direct vision as possible. The achalasic esophagus may be nourished by unusually large aortic esophageal branches. We have gotten away from the term “blunt esophagectomy,” because the more of these operations one does, the more the hiatus is exposed with retractors, and the lateral vascular attachments of the esophagus are divided with long clamps under direct vision. And finally, mobilization of the dilated cervical esophagus in achalasia may be unusually challenging.

For cancer, the issue of lymphadenectomy to allow adequate staging has always been out there. But in 2007, staging of esophageal cancer now routinely includes, in addition to the barium swallow, endoscopy and biopsy, a CAT scan, a PET scan and endoscopic ultrasonography. So I think that our ability to stage patients with esophageal cancer preoperatively is now vastly improved over what it was in the past. And after preoperative chemo- and radiation therapy, restaging scans allow us to know with fair accuracy that we are not leaving a lot of involved lymph nodes behind in the mediastinum. If we do find positive nodes on restaging, we would perform a transthoracic resection and mediastinal lymph dissection, but this is not a common scenario.

After relating how transhiatal esophagectomy was received when I presented this work in 1978, I am the last person in the world to say that an alternative operation–minimally invasive esophagectomy–is not a good approach. It is the new wave. Clearly, however, esophagectomy is one of those operations where experience counts, and where volume is related to patient outcome. And unfortunately, few surgeons in this country develop a large enough volume to become proficient in performing a standard esophagectomy, transthoracic or transhiatal, let alone a minimally invasive mobilization. I am increasingly convinced that one of the most important mandates in this operation is to have a stomach that is pink in the abdomen after gastric mobilization and pink in the neck after delivering the stomach through the posterior mediastinum. Avoiding gastric trauma by gentle handling and not taking vessels too close to the gastric wall so that the stomach is blue and contused is key. We place no traction sutures in the stomach, sew no drains to it, and use no suction devices–nothing to traumatize that tip of the stomach that is brought up into the neck. The stomach is gently mobilized upward through the mediastinum with a hand after my forearm has been passed upward through the mediastinum; and 4 fingers emerge from the cervical incision, ensuring that all vagal fibers and pleural attachments have been divided, and there is a good, free tunnel through which the stomach can be guided. Such tactile “clearing of the way” does not seem possible with the minimally invasive approach.

Another of my concerns with the laparoscopic mobilization of the stomach, and again I speak with no personal experience, is that when I stretch the stomach out on the chest after it has been mobilized and ensure its maximum upward reach has been achieved by “straightening” the natural curvature of the stomach to the right, I find it hard to believe that the stomach can be stretched to its full length within the confines of the abdominal cavity. Therefore, optimal preparation for its reach to the neck may not be achieved laparoscopically. So, for these reasons, I am a little leery about minimally invasive esophagectomy, but time will tell. I am certain that in your hands, Dr. Pellegrini, we will soon be hearing your report of 3000 of these having been done!

Dr. Steven R. DeMeester (Los Angeles, California): You have proven that at a high volume esophageal surgery center, an esophagectomy can be done safely and with low morbidity and mortality. But when it comes to cancer, there is more than just perioperative safety that is important.

Your previous work has demonstrated, and the results have been confirmed worldwide, that with a transhiatal esophagectomy there is about a 35% incidence of local regional failure. Have you seen an improvement in that over time? Or is that a fixed limitation of the transhiatal approach?

Secondly, you have shown that there are an increasing percentage of patients coming with high grade dysplasia for esophagectomy. Do you think that in an era where we have endoscopic ablation techniques and minimally invasive esophagectomy techniques that it may be that a transhiatal resection is too much of an operation for high grade dysplasia?

Dr. Mark B. Orringer (Ann Arbor, Michigan): These are excellent questions. The local recurrence rate, I believe, has unquestionably been lessened because the majority of our patients, 59% in the total group and a larger number in group II patients, have received preoperative chemo- and radiation therapy, which has become the standard of care even though we lack evidence-based data that it makes a substantial difference in survival. But local recurrence after this treatment is far less. The majority of our patients who develop recurrence now have distant disease.

And the controversy over high grade dysplasia rages on. At the University of Michigan, our outstanding GI pathologists, Drs. Appleman, Greenson and McKenna, have reviewed retrospectively our patients with Barrett’s mucosa with high grade dysplasia to determine our institutional experience. The percentage of patients with high grade dysplasia in whom we have carried out an esophagectomy who are found to have adenocarcinoma in the resected specimen. The projections in the literature range from 20% to 50% or more of patients with high grade dysplasia on biopsy who already have cancer in their esophagus. Our pathologists have developed a new set of criteria that were recently presented at their major pathology meeting. Now when they add to the diagnosis “Barrett’s mucosa with high grade dysplasia” the caveat “and features highly suspicious for adjacent carcinoma,” there is a greater than 80% incidence of carcinoma in the specimen that we resect. But when they read only “Barrett’s mucosa with high grade dysplasia,” only 10% of the resected specimens have carcinoma within them. These later patients are those in whom I think we could apply endoscopic ablative techniques. Caution, however, about overuse of such an approach is warranted, because all of us are now operating upon such patients initially treated with endoscopic ablation who later required esophageal resection and were found to have adenocarcinoma beneath re-epithelialized squamous mucosa; their pre-existing adenocarcinoma was “missed” with endoscopic ablation. So I think this is evolving technology that depends in part upon a very close working relationship with experienced GI pathologists.

Dr. Daniel T. Dempsey (Philadelphia, Pennsylvania): I have 2 quick questions.

All of us, or certainly most of us, are less experienced than you with this operation. Are there patients that require an esophagectomy that you do not think ought to have one, or that you would advise us not to approach this way?

Secondly, regarding stricture of the cervical anastomosis, which you allude to in your abstract, a patient occasionally requires an operation to revise that stricture. In our experience, often the anastomosis has gone south somewhat, and is not easy to reach. Could you tell us your experience with operative revision of the cervical anastomosis?

Dr. Mark B. Orringer (Ann Arbor, Michigan): Without question there are contraindications to transhiatal esophagectomy. Patients with mid and upper third cancers with invasion of the tracheobronchial tree and those with stage IV disease are categorically not candidates for the operation. The most important contraindication to transhiatal esophagectomy has not changed in all the years I have performed the operation and that is the surgeon’s judgment on palpation of the esophagus through the hiatus that it is unsafe to proceed. There is no shame in opening the chest. I love to do it. It just is not necessary in most cases. So yes, there are surely patients who should not receive a transhiatal resection.

When first starting to perform transhiatal esophagectomies, nothing breeds success like success. I advise trying the operation for small distal third tumors and those of the esophagogastric junction where an extensive proximal dissection is not required.

Strictures of the cervical esophagogastric anastomosis are a subject unto themselves and will be the topic of a presentation being prepared right now: management of the esophageal anastomosis gone bad. It is terrible for a surgeon to perform this operation, and when cervical dysphagia develops, say goodbye to the patient and send him off to the gastroenterologist, who uses the paradigm that “stricture equals balloon dilatation.” Balloon dilatation is ineffective in treating a cervical esophagogastric anastomotic stricture. If our patients complain of any degree of cervical dysphagia after a transhiatal esophagectomy, we ask them to come back and sit down in our dilating room chair in our clinic. Surgeons performing transhiatal esophagectomy need to have access to their own set of Maloney esophageal dilators. In a patient who develops cervical dysphagia after a transhiatal esophagectomy, we pass 36, 40 and then 46 French Maloney esophageal dilators without anesthesia or sedation. A size 46 French or larger dilator is needed to achieve comfortable swallowing. And patients who keep returning because of dysphagia and in whom there is resistance to passage of a dilator indicating the presence of a “hard stricture,” need to be taught the technique of self-dilatation, because frequent early dilatation, every day for a week, every other day for a week, every third day for a week, and gradually increasing the time interval, will allow these strictures to heal in a patent configuration. Collagen in scar stretches, and if it is stretched frequently enough, it will stay patent and allow the patient to swallow comfortably.

We have had to revise 4 anastomoses in the 30 years we have done these operations. I am reluctant to do this because the anastomosis does drop down into the superior mediastinum. Extending the original cervical incision down over the sternum for an upper partial sternal split to gain access to the anastomosis in the superior mediastinum, and using intraoperative esophagoscopy to identify the anastomosis are very helpful techniques.

Recurrent laryngeal nerve injury is more common in these redo operations. And as is the case with any anastomotic operation, another anastomotic stricture can form, requiring the need for dilatation again. So it is far better to get these strictures dilated and the patients on an aggressive dilatation program to minimize late dysphagia than to revise the anastomosis.

Footnotes

Correspondence: Mark B. Orringer, MD, Professor and Head, Section of General Thoracic Surgery, University of Michigan Medical Center, 2120 Taubman Health Care Center, Box 0344, Ann Arbor, MI 48109. E-mail: morrin@umich.edu.

Reprints will not be available from the author.

REFERENCES

- 1.Orringer MB, Sloan H. Esophagectomy without thoracotomy. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1978;76:643–654. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Denk W. Zur Radikaloperation des Osophaguskarfzentralbl. Chirurg. 1913;40:1065–1068. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Turner GG. Excision of thoracic esophagus for carcinoma with construction of extrathoracic gullet. Lancet. 1933;2:1315–1316. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ong GB, Lee TC. Pharyngogastric anastomosis after oesophagopharyngectomy for carcinoma of the hypopharynx and cervical oesophagus. Br J Surg. 1960;48:193–200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.LeQuesne LP, Ranger D. Pharyngogastrectomy with immediate pharyngogastric anastomosis. Br J Surg. 1966;53:105–109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Akiyama H, Sato Y, Takahashi F. Immediate pharyngogastrostomy following total esophagectomy by blunt dissection. Jpn J Surg. 1971;1:225–231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kirk RM. Palliative resection of oesophageal carcinoma without formal thoracotomy. Br J Surg. 1974;61:689–690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Thomas AN, Dedo HH. Pharyngogastrostomy for treatment of severe caustic stricture of the pharynx and esophagus. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1977;73:817–824. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Orringer MB, Marshall BM, Iannettoni MD. Transhiatal esophagectomy: clinical experience and refinements. Ann Surg. 1999;230:392–400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Halm EA, Lee C, Chassin MR. Is volume related to outcome in health care. A systematic review and methodologic critique of the literature. Ann Intern Med. 2002;137:511–520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dudlei RA, Johansen KL, Brand R, et al. Selective referral of high-volume hospitals: eliminating potentially avoidable deaths. JAMA. 2000;283:1156–1166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Birkmeyer JD, Siewers AE, Finlayson EV, et al. Hospital volume and surgical mortality in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:1128–1137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dimick JB, Cowan JA Jr, Allawadi G, et al. National variation in operative mortality rates for esophageal resection and the need for quality improvement. Arch Surg. 2003;138:1305–1309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Orringer MB, Marshall B, Iannettoni MD. Eliminating the cervical esophagogastric anastomotic leak with a side-to-side stapled anastomosis. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2000;119:277–288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hulscher JB, Tijssen JG, Obertop H, et al. Transthoracic versus transhiatal resection for carcinoma of the esophagus: a meta-analysis. Ann Thorac Surg. 2001;72:306–313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hewitt M, Petitti D. National Cancer Policy Board. Interpreting the Volume-Outcome Relationship in the Context of Cancer Care. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Milstein A, Galvin RS, Delbanco SF, et al. Improving the safety of health care: the Leapfrog initiative. Eff Clin Pract. 2000;3:313–316. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dimick JB, Goodney PP, Orringer MB, et al. Specialty training and mortality after esophageal cancer resection. Ann Thorac Surg. 2005;80:282–286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Devessa SS, Blot WJ, Fraumeni JF. Changing patterns in the incidence of esophageal and gastric carcinoma in the United States. Cancer. 1998;83:2049–2053. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nilsson M, Lagergren J. The relation between today mass and gastro-oesophageal reflux. Best Pract Clin Gastroenterol. 2004;18:1117–1123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wajed SA, Streets CG, Bremmer CG, et al. Elevated body mass disrupts the basses to gastroesophageal reflux. Arch Surg. 2001;136:1014–1019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jacobson BC, Somers SC, Fuchs CS, et al. Body mass index and symptoms of gastroesophageal reflux in women. N Eng J Med. 2006;354:2340–2348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Scipione CN, Chang A, Pickens A, et al. Transhiatal esophagectomy in the profoundly obese. Implications and experience. Ann Thorac Surg. In press. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 24.Orringer MB. Transhiatal esophagectomy without thoracotomy. Operat Tech Thorac Cardiovasc Surg, Spring. 2005;10:63–83. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Orringer MB. Partial median sternotomy: anterior approach to the upper thoracic esophagus. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1984;87:124–129. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Malaisrie SC, Hofstetter WL, Correa AM, et al. The addition of induction chemotherapy to preoperative, concurrent chemoradiotherapy improves tumor response in patients with esophageal adenocarcinoma. Cancer. 2006;107:967–974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Urba SG, Orringer MB, Turrisi A, et al. Randomized trial of preoperative chemoradiation versus surgery alone in patients with locoregional esophageal carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19:305–313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Walsh T, Noonan N, Hollywood D, et al. A comparison of multimodal therapy and surgery for esophageal adenocarcinoma. N Engl J Med. 1996;335:462–467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gebski V, Burmeister B, Smithers BM, et al. Survival benefits from neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy or chemotherapy in oesophageal carcinoma: a meta-analysis. Lancet Oncol. 2007;8:226–234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]