Abstract

Addition of a sterically demanding cyclic (alkyl)(amino)carbene (CAAC) to AuCl(SMe2) followed by treatment with [Et3Si(Tol)]+[B(C6F5)4]− in toluene affords the isolable [(CAAC)Au(η2-toluene)]+[B(C6F5)4]− complex. This cationic Au(I) complex efficiently mediates the catalytic coupling of enamines and terminal alkynes to yield allenes and not propargyl amines as observed with other catalysts. Mono-, di-, and tri-substituted enamines can be used, as well as aryl-, alkyl-, and trimethylsilyl-substituted terminal alkynes. The reaction tolerates sterically hindered substrates and is diastereoselective. This general catalytic protocol directly couples two unsaturated carbon centers to form the three-carbon allenic core. The reaction most probably proceeds through an unprecedented “carbene/vinylidene cross-coupling.”

Keywords: catalysis, enamines, alkynes, transition metal

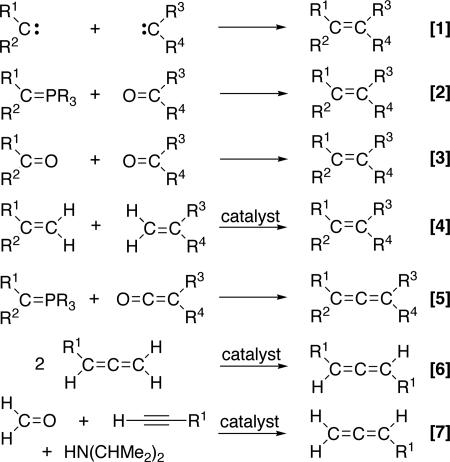

Carbon-carbon bond-forming reactions are at the heart of synthetic organic chemistry; they allow for constructing simple feedstock chemicals as well as complex pharmaceuticals. Among them are reactions that directly couple two different sp2-hybridized carbon centers to form an olefin (1–13). Conceptually, the simplest process would be the dimerization and cross-coupling of two free carbenes (Fig. 1, Eq. 1), but because of the very high reactivity of these species, this route is not selective and is plagued by carbene insertion, cyclopropanation, and other side reactions (14). In marked contrast, when “masked” carbene reagents are used, this synthetic approach is highly effective stoichiometrically and catalytically as exemplified by the Wittig (1), McMurry (2) (Fig. 1, Eqs. 2 and 3), and the olefin metathesis reaction (3, 4) (Fig. 1, Eq. 4), respectively. Most of the stoichiometric processes can be extended to the preparation of allenes (15–17) by analogous “carbene/vinylidene cross-coupling” processes (Fig. 1, Eq. 5). However, there are only two known catalytic methods that couple two fragments to directly form the three-carbon allene core, namely allene cross-metathesis (18) (Fig. 1, Eq. 6), and the Crabbé homologation (19, 20) (Fig. 1, Eq. 7). For the former, a single paper reports that one of the terminal carbon units of a preformed allene can be exchanged to yield a new symmetrically substituted 1,2-diene, although extensive polymerization side reactions occur. The latter, reported in 1979, is a CuBr-mediated three-component reaction among a terminal alkyne, formaldehyde, and diisopropylamine. The most important drawback of this process is that ketones and aldehydes cannot be used in place of formaldehyde, and thus only terminal allenes can be produced.

Fig. 1.

Stoichiometric and catalytic cross-coupling reactions of unsaturated carbon fragments.

In the last decade, allenes have evolved from exotic molecules into extremely useful synthons in natural-product construction (15, 16). Considering the lack of efficient and versatile catalytic processes to assemble directly the skeletal carbons of the allene π-system from two different fragments, a general coupling protocol is highly desirable. Here, we report the synthesis of an isolable cationic Au(I)η2-toluene complex featuring a cyclic (alkyl)(amino)carbene (CAAC) ligand (21–24). We demonstrate its ability to mediate the efficient catalytic coupling of alkynes and enamines to yield a wide range of nonterminal, unsymmetrically substituted, allenes. It is proposed that this cross-coupling reaction proceeds through a unique reaction pathway involving Au(carbene)(vinylidene) intermediates.

Results and Discussion

In the last few years there have been amazing developments in gold catalysis (25–28). Once thought to be a noble metal with little synthetic utility, gold has recently demonstrated its unique and exciting catalytic properties. The most common systems involve LAuCl complexes (L = monodentate ligand), which, through in situ salt metathesis reactions, generate the active species often postulated to be LAu+. Because CAACs have been shown to stabilize cationic species (22), where other ligands were ineffective, they seemed particularly well suited for the preparation of robust LAu+ catalysts.

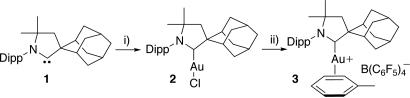

Addition of the novel spirocyclic adamantyl-substituted CAAC (1) with (Me2S)AuCl afforded the prerequisite (CAAC)AuCl (2) in excellent yield (Fig. 2). Reacting a toluene suspension of complex 2 with the silylium-like salt [(Tol)SiEt3]+ [B(C6F5)4]− (29), which is a potent halophile (30), and subsequent removal of all volatiles under high vacuum affords a solid yellow foam. Analysis of a CDCl3 solution of the residue by 1H NMR shows signals in a 1:1 ratio resembling those of carbene 1 and toluene, thus suggesting the formation of cation 3. Its structure was determined unambiguously by a single-crystal x-ray diffraction study (Fig. 3). In the solid state, the toluene molecule is η2-coordinated to the gold center with little perturbation of the aromatic ring, implying weak coordination. Interestingly, complex 3 appeared to be indefinitely stable in solution and in the solid state. Recently, similar complexes bearing very bulky phosphine ligands have been isolated (31).

Fig. 2.

Synthesis of gold catalyst 3.

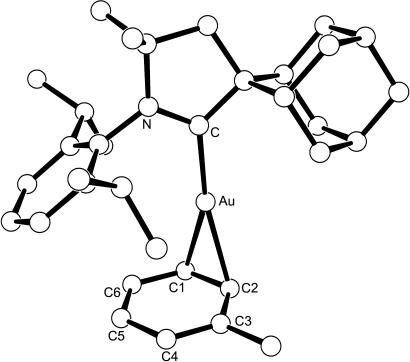

Fig. 3.

Ball and stick depiction of catalyst 3 with 50% displacement ellipsoids. Anions and hydrogen atoms have been omitted. Selected bond lengths [pm]: Au C 201.0(2), Au

C 201.0(2), Au C1 234.1(3), Au

C1 234.1(3), Au C2 232.0(3), C1

C2 232.0(3), C1 C2 142.5(5), C2

C2 142.5(5), C2 C3 141.1(4), C3

C3 141.1(4), C3 C4 137.5(4), C4

C4 137.5(4), C4 C5 144.3(5), C5

C5 144.3(5), C5 C6 136.8(5), C6

C6 136.8(5), C6 C1 141.7(4).

C1 141.7(4).

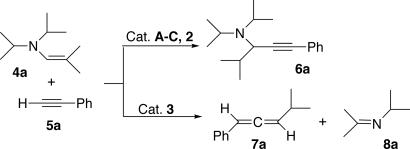

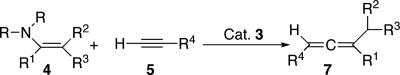

The catalytic activity of 3 was tested toward the gold-catalyzed coupling reaction of enamines 4 with alkynes 5, which is known to yield the corresponding propargyl amines 6 (32–34). Thus, a C6D6 solution of enamine 4a and alkyne 5a were loaded into a J-Young NMR tube containing 5 mol% of complex 3, and the reaction was monitored by 1H NMR spectroscopy. At room temperature no catalytic reaction was observable, even after 24 h. However, upon heating the sample at 90°C, the intensity of the signals for 4a and 5a diminished, and two new resonances, which did not correspond to the expected propargyl amine 6a, appeared in the olefinic region. The 13C NMR spectrum of the crude reaction mixture showed three resonances at 203.7, 102.4, and 95.7 ppm, characteristic of an allene π-system; moreover, traces of imine 8a were detected (imine 8a is partly degraded under the reaction conditions, whereas imine 8b is stable) (Fig. 4). After purification by column chromatography, the allene 7a was unambiguously identified by comparison of its spectroscopic data with those reported in the literature (35). Note that in situ generation of the catalyst 3, prepared by mixing (CAAC)AuCl (2) with one equivalent of KB(C6F5)4, affords similar catalytic results. Importantly, when AuCl (A), AuCl/(Tol)SiEt3+B(C6F5)4−(B), (PPh3)AuCl/KB(C6F5)4 (C), and even the neutral complex (CAAC)AuCl 2 are used as catalysts, the propargyl amine 6a was the major product (>95%), with traces of allene 7a (<2%) detected only in the cases of 2 and (PPh3)AuCl/KB(C6F5)4 C. From these results, it is clear that for the gold center to catalyze allene formation efficiently, it must be coordinated by the CAAC ligand and also rendered cationic by Cl abstraction.

Fig. 4.

Fate of the catalytic cross-coupling of enamine 4a and alkyne 5a depending on the nature of the catalyst.

To test the scope of this catalytic reaction, a set of four different enamines 4 and five terminal alkynes 5 were considered (Table 1). With one exception (entry 15), the corresponding allenes 7 were obtained in moderate to excellent yields. Interestingly, mono-, di-, and tri-substituted enamines can be used, as well as aryl-, alkyl-, and trimethylsilyl-substituted alkynes. The reaction tolerates sterically hindered substrates. Notably, according to multinuclear NMR spectroscopy, all of the allenes obtained by coupling the enamine, which bears R2 = Me and R3 = Ph, were obtained as a single diastereomer (entries 16–20). The only serious limitation that was found is the absence of reaction when an internal alkyne was used, preventing the synthesis of tetrasubstituted allenes (see above).

Table 1.

| Entry | R | R1 | R2 | R3 | R4 | Yields, % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | i-Pr | H | H | Ph | Ph | 70 |

| 2 | i-Pr | H | H | Ph | t-Bu | 80 |

| 3 | i-Pr | H | H | Ph | n-Bu | 71 |

| 4 | i-Pr | H | H | Ph | c-Hex | 70 |

| 5 | i-Pr | H | H | Ph | Me3Si | 40 |

| 6 | i-Pr | H | Me | Me | Ph | 67 |

| 7 | i-Pr | H | Me | Me | t-Bu | 99 |

| 8 | i-Pr | H | Me | Me | n-Bu | 87 |

| 9 | i-Pr | H | Me | Me | c-Hex | 99 |

| 10 | i-Pr | H | Me | Me | Me3Si | 65 |

| 11 | Pyr | Ph | Me | Me | Ph | 71 |

| 12 | Pyr | Ph | Me | Me | t-Bu | 70 |

| 13 | Pyr | Ph | Me | Me | n-Bu | 83 |

| 14 | Pyr | Ph | Me | Me | c-Hex | 86 |

| 15 | pyr | Ph | Me | Me | Me3Si | 0 |

| 16 | i-Pr | H | Me | Ph | Ph | 71 |

| 17 | i-Pr | H | Me | Ph | t-Bu | 80 |

| 18 | i-Pr | H | Me | Ph | n-Bu | 92 |

| 19 | i-Pr | H | Me | Ph | c-Hex | 99 |

| 20 | i-Pr | H | Me | Ph | Me3Si | 55 |

Catalyst 3 (5 mol%), enamine 4 (0.45 mmol), alkyne 5 (0.49 mmol), C6D6 (1 ml), 90° C, 16 h. NMR yields are based on enamines and determined by 1H NMR using benzylmethyl ether as an internal standard. For entries 11–15, the enamine is derived from pyrrolidine (Pyr). Only one distereomer was obtained for entries 16–20.

Mechanistic Investigation.

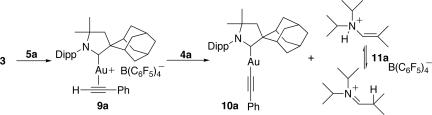

During our catalytic experiments, we noticed that if a C6D6 solution of phenyl acetylene 5a was added to the gold catalyst 3, in the absence of enamines 4, a deep green-colored solution formed rapidly. Upon subsequent addition of enamines 4, the solution immediately turned pale yellow. These observations suggested that two sequential reactions occurred at ambient temperature before active catalysis. To identify the intermediates involved in this two-step process, both the green and yellow solutions were concentrated to dryness, and the residues were characterized by NMR spectroscopy. The 1H NMR spectrum in CD2Cl2 of the green residue 9a shows the absence of toluene and resonances resembling those of the CAAC ligand, as well as those of a single molecule of phenyl acetylene (Fig. 5). To determine the coordination mode of the alkyne and exclude the CH activation of the terminal CH bond, which has been postulated by Wei and Li for related systems (32), we performed a 1H-13C-coupled heteronuclear single quantum correlation NMR experiment. In the 1H part of the spectrum, a singlet resonance at 4.5 ppm, integrating for one H, correlated with two 13C signals at 71 ppm (1J = 262 Hz) and 95 ppm (2J = 45 Hz), indicating that the terminal CH bond of the acetylene was intact. Therefore, the alkyne is most likely η2-cooordinated to the cationic gold center. LAu(η2-alkyne)+X− complexes such as 9a have been proposed as reactive intermediates in numerous catalytic cycles, but only a single isolable example has been reported (36). The yellow solution, resulting from subsequent addition of enamine 4a to a solution of 9a, was identified by 13C and 1H NMR spectroscopy as a 1:1 mixture of the neutral complex 10a (37) and salt 11a (Fig. 5); an independent preparation of 10a and 11a confirmed their identity. Importantly (see below), 11a exists in solution as a mixture of ammonium salt and aldiminium tautomers (4:1 ratio).

Fig. 5.

Stoichiometric addition of alkyne 5a to complex 3 and subsequent reaction of the resulting complex 9a with enamine 4a, which affords acetylide complex 10a and salt 11a.

Complex 10a or salt 11a alone does not mediate the coupling reaction; however, when a 1/1 mixture of independently prepared 10a and 11a (5 mol%) was added to a 1/1.1 solution of enamine 4a and alkyne 5a, the corresponding allene 7a was produced with the same efficiency as when complex 3 was used.

η2-Alkyne and acetylide complexes related to 9a and 10a, as well as salts such as 11a, have been proposed as intermediates in the catalytic preparation of propargyl amines 6 from enamines and alkynes (38). Therefore, it seemed possible that 6 were the precursors of the observed allenes 7, as postulated for the Crabbé homologation (19, 20, 39). Palladium has also been shown to fragment preformed propargylamines to yield allenes. Under our standard coupling conditions, addition of a catalytic amount of 3 to a solution of 6a did not yield allene 7a. This experiment also rules out the possibility of a metal-mediated retroiminoene fragmentation (40) from an in situ-generated η2-propargyl amine gold complex, which can also be represented as an η1-coordinated vinyl cation. Propargyl amine 6a also remained intact after adding a 5 mol% amount of a 10a/11a 1/1 mixture. However, in this case, 5% of allene 7a (equivalent to the amount of coordinated acetylide and ammonium salt added) were obtained, demonstrating that complex 10a and salt 11a are the coupling partners. Lastly, when the coupling reaction of 4a and 5a was performed with a catalytic amount of 3 (or a 1/1 mixture of 10a/11a) in the presence of a 10-fold excess of 6a, the coupling proceeded smoothly without any consumption of 6a. These experiments unambiguously demonstrate that in contrast to the Crabbé homologation, the coupling reactions mediated by catalyst 3 do not involve propargyl amine intermediates.

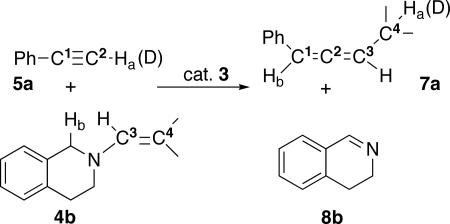

Because of the concomitant formation of imines 8, it is clear that C3 and C4 originate from the enamines 4, and consequently C1 and C2 come from the alkynes 5. To ascertain the exact origin of Ha and Hb in the resulting allene 7a, enamine 4b was reacted with deuterated phenyl acetylene, in the presence of catalyst 3 (Fig. 6); 75% deuterium incorporation was observed for Ha, leading us to conclude that Ha and Hb come from the alkynes 5 and the α-position of the nitrogen moiety of enamines 4, respectively. Note, that in this case imine 8b has been isolated (as mentioned above, imine 8a is partly degraded under the reaction conditions, whereas imine 8b is stable), and its spectroscopic data compared with those reported in the literature (41).

Fig. 6.

Origin of the various fragments of the resulting allene 7a.

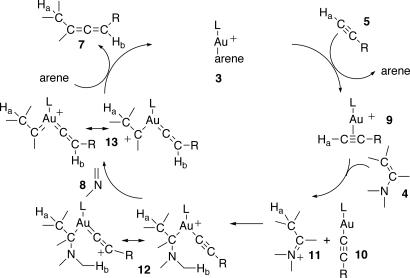

Taking the above data as a whole, the catalytic cycle depicted in Fig. 7 can be postulated. Complex 3 undergoes ligand substitution of the coordinated arene by alkynes 5 to yield the isolated Au(I) η2-alkyne adducts 9. Subsequent proton abstraction of Ha from the activated terminal alkynes with enamines 4 affords a mixture of the neutral Au(I) acetylide complexes 10 and ammonium salts 11 (represented as their iminium tautomers). Oxidative addition (42) of 11 to 10 produces the transient cationic Au(III) alkyl complexes 12, which can also be regarded as allenyl-like cations. Hydride transfer of Hb from the α-position of the amine moiety to the positively charged carbon results in the formation of imines 8 and Au(carbene)(vinylidene) intermediates 13. As recently reviewed by Gorin and Toste (25) and Fürstner and Davies (27), the representation of the carbene ligand of 13 as a gold-stabilized carbocation is perfectly valid and in this case helps to avoid the uncommon Au(V) oxidation state. Reductive coupling of the carbene and vinylidene produces allenes 7 and regenerates the catalyst 3.

Fig. 7.

Proposed catalytic cycle for the cross-coupling of enamines 4 with alkynes 5 leading to allenes 7.

Concluding Remarks.

The cross-coupling reaction of enamines with terminal alkynes, mediated by the cationic gold(I) complex 3, which bears a CAAC ligand, is a general catalytic protocol that directly couples two unsaturated carbon centers and forms the three-carbon allenic core. The reaction most probably proceeds through an unprecedented carbene/vinylidene cross-coupling. The diastereoselectivity observed is encouraging, and consequently an enantioselective version of this catalytic reaction, using the appropriate optically pure CAAC ligand should be possible.

Materials and Methods

For more details on the procedures used, see supporting information (SI) Materials and Methods.

CAAC 1.

Diethyl ether (15 ml) was added at −78°C to a Schlenk tube containing the conjugate acid of CAAC 1 with HCl2− as counteranion (900 mg, 2.0 mmol) and potassium bis(trimethylsilyl)amide (800 mg, 4.0 mmol). The reaction mixture was stirred for 5 min and then removed from the cold bath as stirring was continued until the solution reached room temperature. The solvent was removed under vacuum, and the residue was extracted with n-hexane (3 × 10 ml). After removing the solvent under vacuum, CAAC 1 was isolated as white microcrystalline solid (710 mg, 94% yield). Crystals suitable for a single crystal x-ray diffraction study were obtained from an n-hexane solution at −20°C. 1H NMR (300 MHz, C6D6) δ 7.23 (t, J = 7.0 Hz, 1H), 7.15 (d, J = 7.2 Hz, 2H), 3.56 (m, 2H), 3.08 (sept, 3J = 6.8 Hz, 2H), 2.21–1.62 (m, 14H), 1.23 (d, 3J = 6.8 Hz, 6H), 1.12 (d, 3J = 6.8 Hz, 6H), 1.11 (s, 6H); 13C NMR (75 MHz, C6D6) δ 322.7, 146.3, 138.9, 128.4, 124.1, 81.2, 69.2, 48.7, 39.7, 38.8, 35.6, 35.3, 30.0, 29.8, 29.7, 28.6, 26.4, 22.3.

AuCl(CAAC) Complex 2.

A THF solution (6 ml) of free carbene 1 (640 mg, 1.69 mmol) was added to a THF solution (5 ml) of AuCl(SMe2) (475 mg, 1.61 mmol). The reaction mixture was stirred for 12 h at room temperature. The solvent was removed under vacuum, and the residue was washed with n-hexane (10 ml). The residue was extracted with methylene chloride (10 ml), and the solvent was removed under vacuum, affording complex 2 as a white solid (850 mg, 86% yield). Crystals suitable for an x-ray diffraction study were obtained by slow evaporation of a CH2Cl2 solution. m.p. 194–195°C (dec); 1H NMR (300 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.37 (t, J = 7.7 Hz, 1H), 7.20 (d, J = 7.7 Hz, 2H), 4.00 (m, 2H), 2.71 (sept, 3J = 6.7 Hz, 2H), 2.32–1.78 (m, 14H), 1.39 (d, 3J = 6.7 Hz, 6H), 1.31 (s, 6H), 1.26 (d, 3J = 6.7 Hz, 6H); 13C NMR (75 MHz, C6D6) δ 239.9, 144.8, 135.2, 129.7, 125.0, 76.9, 63.7, 48.5, 39.0, 37.0, 35.2, 34.6, 29.2, 29.1, 27.6, 27.1, 26.9, 23.1; fast atom bombardment MS calculated for C27H39NAu [M]+: m/z 574; found 574.

[Au(CAAC)(Toluene)]+ [B(C6F5)4]− Catalyst 3.

Toluene (5 ml) was added at room temperature to a Schlenk tube containing complex 2 (1.48 g, 2.43 mmol) and [(Tol)SiEt3]+ [B(C6F5)4]− (2.15 g, 2.43 mmol). After stirring the biphasic mixture for 30 min., n-hexane (50 ml) was added. The upper layer was removed by cannula, and the oily residue was dried under high vacuum to afford complex 3 as a solid white foam (3.04 g, 93% yield). Crystals suitable for an x-ray diffraction study were obtained by layering a fluorobenzene solution of 3 with n-hexane. m.p. 156–157°C (dec); 1H NMR (300 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.52 (t, J = 7.8 Hz, 1H), 7.31 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 2H), 7.23–7.19 (m, 4H), 7.02 (m, 1H), 3.05 (m, 2H), 2.57 (sept, 3J = 6.7 Hz, 2H), 2.33 (s, 3H, CH3), 2.34–1.34 (m, 14H), 1.38 (s, 6H), 1.29 (d, 3J = 6.7 Hz, 6H), 1.25 (d, 3J = 6.7 Hz, 6H); 13C NMR (75 MHz, CDCl3) δ 237.0, 148.4 (m, 1J = 245 Hz), 145.7, 144.7, 138.3 (m, 1J = 241 Hz), 136.5 (m, 1J = 241 Hz), 135.9, 130.9, 127.2, 125.7, 123.8, 117.1, 79.1, 63.7, 48.4, 38.6, 36.9, 35.2, 34.1, 29.5, 29.2, 27.6, 26.9, 26.7, 23.2.

General Catalytic Procedure for the Preparation of Allenes 7.

A C6D6 solution (1 ml) of enamines 4 (0.446 mmol) and alkynes 5 (0.490 mmol) was added to a J-Young NMR tube containing catalyst 3 (30 mg, 0.023 mmol) and benzylmethyl ether as internal standard (5 mg, 0.041 mmol). The tube was sealed and heated at 90°C for 16 h, and the yields of the resulting allenes were calculated by 1H NMR spectroscopy.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grant R01 GM 68825 (to G.B.) and RHODIA, Inc. (G.B.). G.D.F. and S.K. were supported by fellowships from the Alexander von Humboldt Foundation and the Higher Education Commission of Pakistan, respectively.

Abbreviation

- CAAC

cyclic (alkyl)(amino)carbene.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

Data deposition: The atomic coordinates have been deposited in the Cambridge Structural Database, Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre, Cambridge CB2 1EZ, United Kingdom (CSD reference nos. 651272–651275).

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/cgi/content/full/0705809104/DC1.

References

- 1.Takeda T, editor. Modern Carbonyl Olefination. Weinheim, Germany: Wiley; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fürstner A, Bogdanovic B. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 1996;35:2442–2469. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Grubbs RH, editor. Handbook of Metathesis. Weinheim, Germany: Wiley; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schrock RR, Czekelius C. Adv Synth Cat. 2007;349:55–77. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Li JJ, Corey EJ, editors. Name Reactions of Functional Group Transformations. New York: Wiley; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Herrerias CI, Yao X, Li Z, Li C. Chem Rev. 2007;107:2546–2562. doi: 10.1021/cr050980b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fagnoni M, Dondi D, Ravelli D, Albini A. Chem Rev. 2007;107:2725–2756. doi: 10.1021/cr068352x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yin L, Liebscher J. Chem Rev. 2007;107:133–173. doi: 10.1021/cr0505674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Alberico D, Scott ME, Lautens M. Chem Rev. 2007;107:174–238. doi: 10.1021/cr0509760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Takanori S. Adv Synth Cat. 2006;348:2328–2336. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chopade PR, Louie J. Adv Synth Cat. 2006;348:2307–2327. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kuehn FE, Scherbaum A, Herrmann WA. J Organomet Chem. 2004;689:4149–4164. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Trost BM, Frederiksen MU, Rudd MT. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2005;44:6630–6666. doi: 10.1002/anie.200500136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Moss RA, Platz MS, Jones M Jr, editors. Reactive Intermediate Chemistry. New York: Wiley; 2004. pp. 273–461. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brummond KM, DeForrest J. Synthesis. 2007:795–818. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Krause N, Hashmi ASK, editors. Modern Allene Chemistry. Weinheim, Germany: Wiley; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Aksnes G, Froyen P. Acta Chem Scand. 1968;22:2347–2352. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ahmed M, Arnauld T, Barret AGM, Braddock DC. Org Lett. 2000;2:551–553. doi: 10.1021/ol0055061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Crabbé P, André D, Fillion H. Tetrahedron Lett. 1979;20:893–896. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Searles S, Li Y, Nassim B, Lopes MTR, Tran PT, Crabbé P. J Chem Soc Perkin Trans. 1984;1:747–751. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lavallo V, Canac Y, Präsang C, Donnadieu B, Bertrand G. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2005;44:5705–5709. doi: 10.1002/anie.200501841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lavallo V, Canac Y, DeHope A, Donnadieu B, Bertrand G. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2005;44:7236–7239. doi: 10.1002/anie.200502566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Frey GD, Lavallo V, Donnadieu B, Schoeller WW, Bertrand G. Science. 2007;316:439–441. doi: 10.1126/science.1141474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Anderson DR, Lavallo V, O'Leary DJ, Bertrand G, Grubbs RH. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2007 doi: 10.1002/anie.200702085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gorin DJ, Toste FD. Nature. 2007;446:395–403. doi: 10.1038/nature05592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jiménez-Núñez E, Echavarren AM. Chem Commun. 2007:333–346. doi: 10.1039/b612008c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fürstner A, Davies PW. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2007;46:3410–3449. doi: 10.1002/anie.200604335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hashmi ASK, Hutchings GJ. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2006;45:7896–7936. doi: 10.1002/anie.200602454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lambert JB, Zhang S, Stern CL, Huffman JC. Science. 1993;260:1917–1918. doi: 10.1126/science.260.5116.1917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Douvris C, Stoyanov ES, Tham FS, Reed CA. Chem Commun. 2007:1145–1147. doi: 10.1039/b617606b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Herrero-Gómez E, Nieto-Oberhuber C, López S, Benet-Buchholz J. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2006;45:5455–5459. doi: 10.1002/anie.200601688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wei C, Li C. J Am Chem Soc. 2003;125:9584–9585. doi: 10.1021/ja0359299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kantam ML, Prakash BV, Reedy CRV, Sreedhar B. Synlett. 2005;15:2329–2332. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lo VKY, Liu Y, Wong MK, Che CM. Org Lett. 2006;8:1529–1532. doi: 10.1021/ol0528641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jayanth TT, Jeganmohan M, Cheng MJ, Chu SY, Cheng CH. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:2232–2233. doi: 10.1021/ja058418q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Akana JA, Bhattacharyya KX, Müller P, Sadighi JP. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:7736–7737. doi: 10.1021/ja0723784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wang HMJ, Chen CYL, Lin IJB. Organometallics. 1999;18:1216–1223. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Koradin C, Gommermann N, Polborn K, Knochel P. Chem Eur J. 2003;9:2797–2811. doi: 10.1002/chem.200204691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nakamura H, Onagi S, Kamakura T. J Org Chem. 2005;70:2357–2360. doi: 10.1021/jo0479664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ipatktschi J, Mohsseni-Ala J, Dülmer A, Loschen C, Frenking G. Organometallics. 2005;24:977–989. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nicolaou KC, Mathiason CJN, Montagnon T. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:5192–5201. doi: 10.1021/ja0400382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Raubenheimer HG, Olivier PJ, Lindeque L, Desmet M, Hrusak J, Kruger GJ. J Organomet Chem. 1997;544:91–100. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.