Abstract

Exposure of animals to hyperoxia decreases lung VEGF mRNA expression concomitant with an acute increase in VEGF protein within the epithelial lining fluid (ELF). The VEGF concentration in ELF is in excess of that found in the plasma, leading to the hypothesis that hyperoxia stimulates the release of VEGF protein from stores within the extracellular matrix. To test this hypothesis in a cell culture system, we exposed A549 cells to 95% O2 for 48 hrs followed by recovery in room air (RA) for 24 hrs. We found that Ox increased VEGF protein 2- to 3-fold within the medium at 48 hrs of exposure and during recovery. Heparin clearing revealed the medium to contain a 50:50 mixture of the heparin-binding (VEGF165) and heparin-non-binding (VEGF121) proteins and Ox to increase both proteins equally. Transcriptional activation of VEGF appears unlikely to explain the increase in VEGF protein as full-length and splice variant VEGF mRNA expression were unchanged by hyperoxia. Analysis of cell-associated VEGF proteins found that Ox increased the expression of VEGF121 and VEGF165 proteins. Blocking binding sites with exogenous heparin enhanced VEGF protein in the medium from RA grown cells while heparinase digestion of bound VEGF revealed a greater reserve of VEGF protein in RA cells. Collectively these findings indicate that hyperoxia enhances the expression of VEGF121/165 proteins and facilitates the release of VEGF165 from cell-associated stores. Increases in VEGF in ELF may represent an adaptive response fostering cell survival and type II cell proliferation in O2-induced lung injury.

Keywords: vascular endothelial growth factor, acute lung injury, hyperoxia

INTRODUCTION

Pulmonary epithelial-mesenchymal cell interactions foster the mutual maturation and structural development of alveolar and vascular systems. Regulation of this complex paradigm involves numerous growth factors including the vascular endothelial cell growth factor family (VEGF A-D). VEGF is an endothelial cell mitogen, whose primary pulmonary repository is the alveolar type II cell [1]. VEGF-A is a 34-46 kD homodimeric glycoprotein existing in several isoforms secondary to post-transcriptional mRNA splicing of the native VEGF gene. The resulting splice variants differ in the presence or absence of sequences encoded by exons 6 and 7, which contain basic amino acid sequences with high affinity for heparin and heparan sulfate moieties [2]. Variable splicing within these regions results in numerous isoforms, the most common of which are 206, 189, 165, 145, and 121 amino acids in length. Secreted peptides containing both exons (VEGF206 and VEGF189) are tightly bound to extracellular matrix (ECM) and cell surface heparan sulfates, while those lacking one exon (VEGF165 and VEGF145) possess modest diffusion and heparan-binding potential. VEGF121, which lacks both exons, is acidic and easily diffusible. Within the lung, VEGF proteins 189, 165, and 121 are preferentially expressed by alveolar epithelial cells [1].

Regulation of VEGF protein expression is complex, involving transcriptional, post-transcriptional, translational, and post-translational processes. Transcriptional control involves a promoter region, which is responsive to hypoxia, oncogenes, and growth factors. Stabilization of hypoxia inducible factor 1α (HIF-lα) permits formation of a heterodimer with HIF-1β, which binds the hypoxia-response element and induces VEGF mRNA expression [3]. In transcripts containing a lengthy 5'-untranslated region (UTR) with complex secondary structure like VEGF, cap-dependent translation is inefficient [4]. To bypass this inhibition, VEGF contains two internal ribosome entry sites (IRES), embedded start codons remote from the 5'-terminus. Post-translational processing of VEGF proteins occurs through proteolytic cleavage. The plasmin cleavage product of VEGF165 (VEGF110) is markedly less mitogenic toward endothelial cells that the parent protein [5].

Suppression of any of these regulatory pathways during development can attenuate VEGF protein expression and severely hinder pulmonary morphogenesis. Rodent and primate models of hyperoxia display similar decrements in VEGF protein and mRNA [6-9]. During neonatal oxygen injury in the rabbit, VEGF mRNA isoform expression is not only suppressed, but the ratio of VEGF189 to VEGF121 mRNA is dramatically reduced [10]. Despite the diminished VEGF expression, hyperoxia often induces a paradoxical rise in VEGF protein obtained from epithelial lining fluid (ELF) [6, 10]. Given that plasma concentrations of VEGF are barely detectable during the same period, transudation of plasma VEGF into the alveolar space appears unlikely [6].

Pulmonary overexpression of VEGF has been shown to induce widespread capillary leakage and endothelial cell discontinuity, suggesting that enhanced alveolar VEGF promotes the early pulmonary edema noted during respiratory distress syndrome (RDS) and acute lung injury (ALI) [11, 12]. Recent information also supports a reparative, anti-apoptotic role for VEGF in the RDS and ALI [13-15]. In the fetus, appropriate levels of pulmonary VEGF are paramount to normal vascular and alveolar development [16]. Clinical reductions in lung VEGF mRNA and protein are associated with the development of bronchopulmonary dysplasia (BPD) in premature infants, a form of neonatal chronic lung disease characterized by a reduction in alveolar number and microvascular density [17, 18]. Conceptually, hyperoxia-induced VEGF secretion could have both positive and negative effects in the oxygen-exposed newborn lung, promoting cellular survival and propagating capillary leak into the alveolar space. Understanding the mechanism whereby enhanced VEGF secretion occurs, therefore, is essential to designing therapies aimed at improving pulmonary outcomes while minimizing lung injury.

Although it has been speculated that hyperoxia-induced increases in ELF VEGF emanates from proteolytic release of matrix- and receptor-bound VEGF isoforms, scientific validation of this premise is lacking. Accordingly, we undertook the present study to determine if in vivo results could be replicated in cell culture and to ascertain the nature of the hyperoxia-mediated increases in secreted VEGF. We hypothesized that hyperoxia would increase secreted VEGF through reductions in cell surface and ECM-bound VEGF165 in the type II cell-like adenocarcinoma cell line, A549. Our findings indicate that augmented VEGF secretion originates from greater VEGF protein expression in conjunction with the enhanced release of bound VEGF.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Reagents and Supplies

Antibodies were purchased from the corresponding suppliers: anti-human VEGF-A189/165/121 (A-20) from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc. (Santa Cruz, CA), anti-human VEGF-A from Becton Dickenson/Pharmingen (San Diego, CA), anti-HIF-1α from Cell Signaling Technology (Danvers, MA), anti-HIF-2α from Novus Biologicals (Littleton, CO), and anti-β-actin from Sigma Chemical (St. Louis, MO). Medium was purchased from Cellgro/Mediatech, Inc. (Herndon, VA). Human VEGF-A Quantikine ELISA kits were purchased from R&D Systems (Minneapolis, MN). Human VEGF and β-actin primers and controls for RT-PCR were obtained in the Dual-PCR kit from Maxim Biotech, Inc. (South San Francisco, CA). Real-time primers were produced by the core facility at Dartmouth College of Medicine. RNeasy RNA extraction kit was purchased from Qiagen (Valencia, CA). Heparin Sepharose 6 Fast Flow beads, L-(4,5-3H)leucine and mouse/rabbit HRP-IgG were obtained from Amersham Pharmacia Biotech (Piscataway, NJ). Pre-cast gels, Trizol, and Taq DNA polymerase were purchased from Invitrogen Corp. (Carlsbad, CA) and chemiluminescence detection was received from Pierce (Rockford, IL). Reverse Transcription (RT) System kit was purchased from Promega (Madison, WI). SYBR Green Mater Mix was obtained from Applied Biosystems (Foster City, CA). Microcon centrifugal filter tubes were purchased from Millipore (Bedford, MA). VEGF121 and VEGFA peptides were obtained from GenWay Biotech, Inc. (San Diego, CA). The remaining reagents and chemicals were obtained from Sigma Chemical (St. Louis, MO).

Cell culture and conditions

The human lung adenocarcinoma cell line, A549 (ATCC, Manassas, VA), was grown in Ham's F12 supplemented with 10% FBS, 100 IU/ml of penicillin, 100 mg/ml streptomycin, and 2 mM glutamine. Normal, human lung fibroblasts (passage 4-10) were grown in a 1:1 mixture of Minimal Essential Medium for cell suspension and Leibowitz 15 medium supplemented with 10% FBS, 100 IU/ml of penicillin, 100 mg/ml streptomycin, and 2 mM glutamine. Cells were allowed to attach overnight and the following morning, medium was refreshed and plates divided into room air (RA) and hyperoxic groups (Ox). Plates in the RA group were returned to the incubator to grow in room air + 5% CO2 while plates in the Ox group were loaded into a sealed, humidified chamber flushed twice daily for 15 minutes with a 95% O2/ 5% CO2 gas mixture (Billups-Rothenburg Inc, Del Mar, CA). Plates were removed at 24 and 48 hours for analysis. After 48 hours of exposure, RA and Ox plates were removed from the chambers, supplemented with fresh medium, and replaced in the incubator in room air for an additional 24 hours (Recovery, Rec). To study the ability of heparin to displace VEGF from the cell, 10 μg/ml of sodium heparin was added to each well prior to start of the experiments.

VEGF ELISA

Medium was removed from wells at specified times, centrifuged at 1000 × g to remove particulates, and frozen at −20°C. The remaining monolayers were trypsinized and the cells counted to normalize VEGF protein values. The VEGF ELISA was performed according to the manufacturer's specifications. Briefly, 200 μl of medium were added to microplate wells containing a monoclonal VEGF165/121 antibody bound to the surface. Following incubation for 2 hours, wells were washed three times and incubated for 2 hours with polyclonal VEGF-HRP conjugate. After washing, detection reagent was added for 20 minutes and plates immediately analyzed on a microplate reader (Tecan Sunrise, Mannedorf, Switzerland) at 450 nm with λ correction at 540 nm. VEGF values were derived from a standard curve of known concentrations of recombinant human VEGF165. Each sample was analyzed in duplicate and averaged. To clear medium of heparin-binding proteins, 200 μl of washed, heparin Sepharose 6 beads were incubated with 450 μl of medium overnight at 4°C. Medium was separated from the beads by centrifugation and the ELISA performed as described above.

Real-time RT-PCR

RNA for real-time PCR was collected from trypsinized cells using Trizol and extracted with chloroform. The RNA was then precipitated in isopropanol, washed in 70% ethanol and vacuum dried. Pellets were reconstituted in RNase-free water and heated to dissolve. The amount and purity of the RNA was determined by spectrophotometry. Reverse transcription was performed using dNTP, oligo dt, AMV reverse transcriptase, and RNase inhibitor from a commercially available RT kit. Real-time PCR (DNA Engine Opticon, MJ Research) was then performed on 2 μl of RT product using β-actin as control. RT product was mixed with SYBR Green Master Mix and VEGF primers (5′-TGTCTTGCTCTATCTTTCTT-3′, lower; and 5′-CTTGCCTTGCTGCTCTACCT-3, upper′). Standard curves were run concurrently. Conditions for PCR were 2 minutes at 94°C, 15 seconds at 94°C, 1 minute at 60°C, 1 minute at 72°C, followed by 39 cycles of 15 seconds at 94°C, 1 minute at 60°C, 1 minute at 72°C. The specificity of the amplified PCR product was verified by the analysis of the melting curves, which were product-specific. Agarose gel electrophoresis of PCR product revealed a single band for VEGF and β-actin. A standard graph of CT values obtained from serially-diluted genes was constructed for all reactions. CT values were converted to gene copy number by instrument software and normalized to that of our control gene, β-actin. Changes in fold over baseline values for VEGF (T0) were then reported.

RT-PCR

RNA was collected using RNeasy according to the manufacturer's protocol. RNA quantity and purity were assessed spectrophotometrically. Synthesis of cDNA was conducted using 0.5 μg of total RNA, RNase inhibitor, dNTPs, and reverse transcriptase, in RT buffer (250 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.3, 375 mM KCl, 15 mM MgCl2, 50 mM DTT) supplied in the Maxim Dual-PCR kit. PCR amplification was then performed using VEGF189, VEGF165, VEGF121, and β-actin primers or VEGF and β-actin control cDNA from the kit. Equal volumes of PCR product were separated by electrophoresis on 1.5% agarose gels. Gels were then scanned on a Typhoon imager (GE Healthcare, Piscataway, NJ), digitized, and stored for analysis.

Protein synthesis

Protein synthesis was determined by measuring the incorporation of L-[4,5-3H]leucine (4 μCi/ml, final concentration) into protein after a 1-hour labeling period. Following incubation, monolayers were rinsed with ice-cold PBS prior to precipitation with 10% trichloroacetic acid for 15 minutes. Precipitated proteins were then dissolved in 0.5 N NaOH and the corresponding radioactivity measured by liquid scintillation counting.

Immunoblotting

Cell monolayers were rinsed with PBS, trypsinized, and lysed in western lysis buffer at 2000 cells/μl [20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM Na2EDTA, 1 mM EGTA, 1% Triton X-100, 2.5 mM sodium pyrophosphate, 1 mM β-glycerophosphate, 1 mM Na3VO4, 1 μg/ml leupeptin, and 0.5 mM PMSF (final concentrations)]. Lysates were passed through a 28-gauge needle three times and supernatants collected following centrifugation at 1000 × g. Lysates from whole cell extracts representing equal cell numbers were resolved on either 12% or 4-12% Bis-Tris gels. Resolved proteins were transferred to PVDF membranes and incubated overnight at 4°C with primary antibodies [VEGF189/165/121 (1:500), HIF-1α (1:1000), HIF-2α (1:1000), and β-actin (1:5000)] in 5% non-fat dry milk blocking buffer. Following rinsing, membranes were incubated with the corresponding HRPconjugated secondary antibody (1:5000) and the signal detected by chemiluminescence. Values were normalized to β-actin expression.

Determination of VEGF isoforms within the medium was performed on cell culture medium that was volume-reduced by centrifugation in 10 kD exclusion columns. Following volume reduction, equal quantities of medium were separated and blotted as described.

Digestion of heparin-bound proteins

At each time point, medium was replaced with Ham's F12 without supplements and incubated in the respective environment for 60 minutes. Cells were then scraped from the wells, spun at 1000 × g for 5 minutes, washed in PBS, and re-pelleted. Heparinase III, at a concentration of 3.3 mU/100k cells (0.05 U/ml), was then added to each tube and incubated for 60 minutes at 37°C. Tubes were centrifuged to pellet cells and supernatants removed. Heparinase digests were then concentrated in Microcon centrifugal filter tubes to collect proteins with size greater than 10 kD. Equal volumes of concentrated digests were then blotted as described.

Statistics

All studies were performed a minimum of 3 times. Data were analyzed using 2- or -way analysis of variance. When a significant trend of oxygen, time, or an interaction of both was identified, post-hoc analysis using Fisher's LSD testing to determine individual differences was performed. Real-time data at baseline was used to determine the fold change in RA and Ox groups. Normalized values were then analyzed by non-paired, student's t tests with Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons. Data are listed as mean ± standard error and the level of significance set at p<0.05.

RESULTS

Hyperoxia increases secreted VEGF

In actively dividing A549 cells, exposure to 95% O2 for more than 48 hours results in necrotic cell death [19]. For this reason, we exposed A549 cells to 48 hours of 95% O2 followed by 24 hours of recovery in room air. Our preliminary studies illustrated that this strategy resulted in growth arrest during the 72-hour study period and minimal cell death as documented by stagnant cell number, markedly diminished incorporation of [3H]thymidine into DNA, and Trypan blue exclusion (not shown).

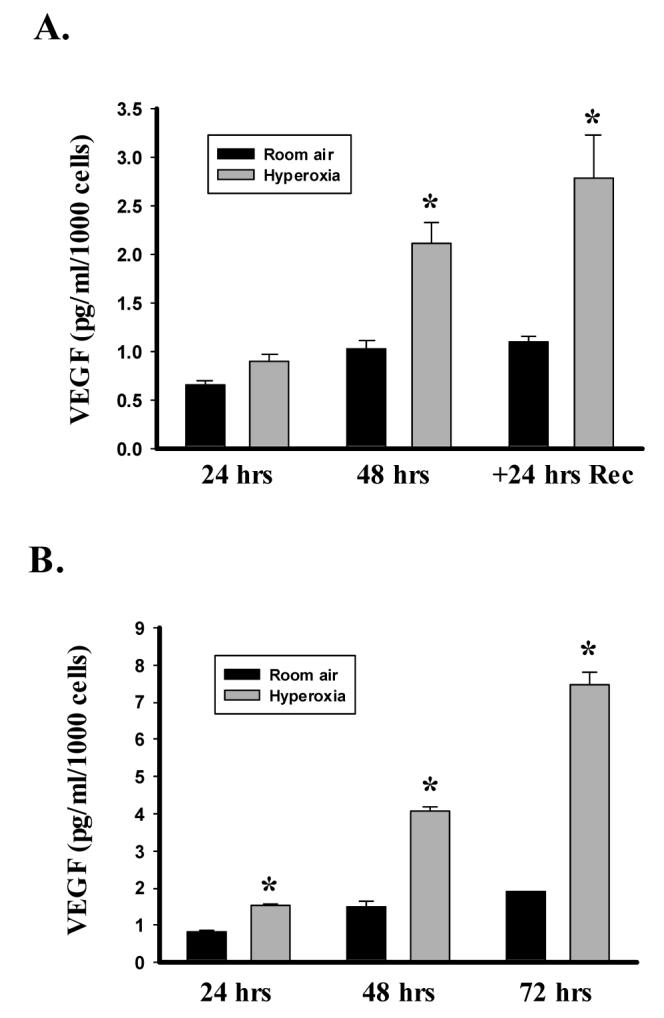

To explore the effect of hyperoxia on VEGF, we measured medium-derived VEGF with a commercially available ELISA. Control studies indicated that medium containing 10% FBS had undetectable levels of VEGF while incubation of A549 cells with 100 μM desferoximine, which stabilizes HIF, increased medium-derived VEGF by 4.5-fold within 24 hours. In growing A549 cells, VEGF concentrations in the medium increased over time. In RA cells, VEGF increased from 24 to 48 hours, but remained constant during recovery. By comparison, hyperoxia lead to a time-dependent increase in secreted VEGF concentrations with respect to time and compared to RA, such that concentrations at 48 hours and during recovery were 2- to 3-fold higher than in RA cells (Fig 1A). To insure that our findings were not unique to the A549 cell line, we also exposed normal, neonatal lung fibroblasts to hyperoxia, cells previously shown to increase VEGF protein expression in response to activated factor VII and TGF-β [20, 21] Because these cells are more resistant to oxygen-induced cell death, we exposed them to hyperoxia for the full 72-hour study period [22]. As was observed in the A549 cells, hyperoxia markedly increased secreted VEGF over time and relative to room air-exposed cells (Fig 1B). Given the similar responses in the two cell lineages, we chose to further investigate the effects of hyperoxia on VEGF using only A549 cells.

Figure 1.

Hyperoxia increases secreted VEGF. VEGF in the medium was determined by ELISA and values corrected to cell number from the corresponding well. A. Histogram illustrating the effect of exposing A549 cells to 95% O2 (Hyperoxia) or room air for 48 hrs and the allowing recovery in room air for an additional 24 hrs (+24 hrs Rec). B. Lower histogram shows the effect of exposing human neonatal lung fibroblasts to 95% O2 or room air for 72 hrs. Columns represent mean (n=3) and bars standard error of the mean. *Denotes p<0.05 between hyperoxia and room air groups at same time point.

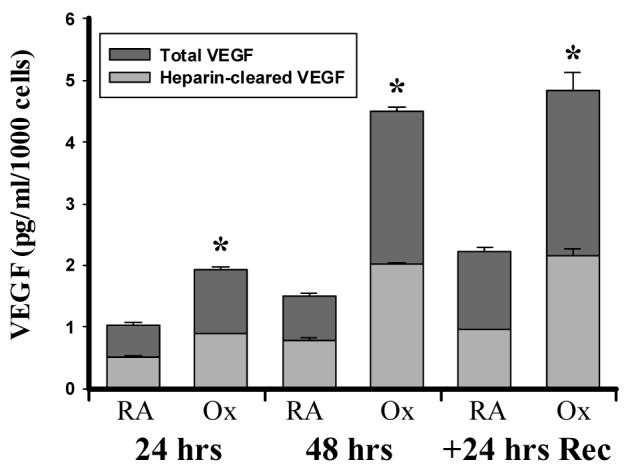

Hyperoxia increases the secretion of VEGF isoforms with and without heparin-binding capacity

The heparin and heparan-sulfate binding characteristics of the VEGF splice variants determines their solubility. Of the various isoforms, VEGF121 is freely diffusible secondary to the absence of the heparin-binding region, while VEGF165 remains partially bound to ECM forming a “reserve” of readily available protein. After volume-reducing the medium with fractional spin columns, we confirmed the presence of only two VEGF isoforms in the medium by immunoblotting (not shown). Further delineation of the contributions of the soluble VEGF isoforms was undertaken using affinity chromatography. Since the ELISA utilizes an antibody that recognizes only VEGF165 and VEGF121, we cleared the medium of heparin-binding moieties by prior assaying for VEGF. We observed that heparin clearing decreased VEGF secretion by approximately 50% in all groups regardless of the oxygen concentration or timing of the sample (Fig 2). Heparin-clearing had no impact on the time-dependent or hyperoxia-mediated increases in VEGF concentrations. This implies that medium-derived VEGF is a 50/50 mixture of VEGF165 and VEGF121 under both RA and Ox conditions.

Figure 2.

Hyperoxia increases the secretion of VEGF isoforms with and without heparin-binding capacity. A549 cells were exposed to 95% O2 (Ox) or room air (RA) for 48 hrs and then allowed to recover in room air for 24 hrs (+24 hrs Rec). Aliquots of medium were affinity purified with heparin-binding beads as described under MATERIALS AND METHODS. VEGF protein levels in the purified and unpurified samples were then determined by ELISA and corrected to cell number. Columns represent mean (n=3) and bars standard error of the mean. *Denotes p<0.05 between Ox and RA groups at same time point.

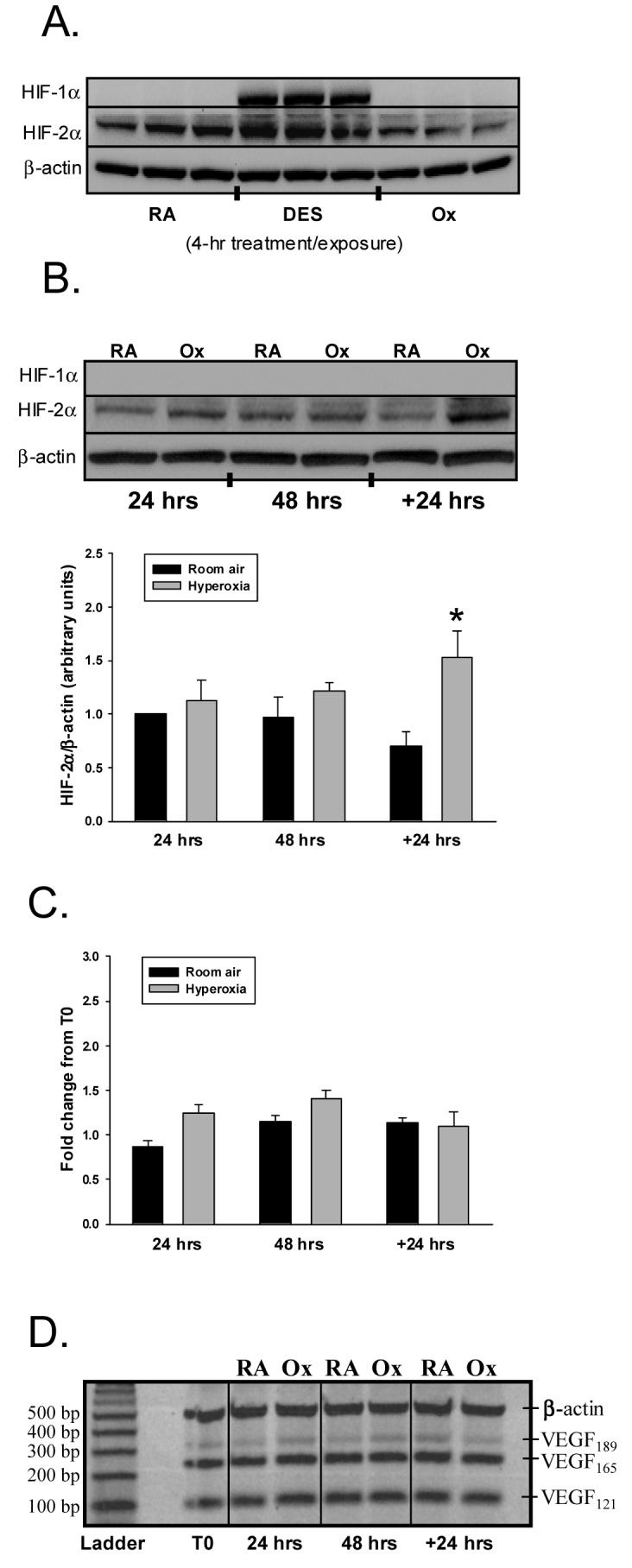

Hyperoxia does not increase VEGF transcription

As an initial step toward deciphering the origin of hyperoxia-mediated increases in VEGF secretion, we explored the effects of hyperoxia on the transcriptional activation of VEGF. During hypoxia, expression of VEGF is enhanced by stabilization of HIF. To confirm the presence of intact HIF signaling, we immunoblotted whole cell lysates with HIF-1α and HIF-2α antibodies following treatment with desferoximine for 4 hours. As represented in Figure 3A, desferoximine significantly increased HIF-1α and HIF-2α protein expression. Despite the presence of intact HIF pathways, we were unable to detect HIF-1α protein at 4, 24, and 48 hours of exposure or during recovery in either RA or Ox cells (Fig 3B). Although HIF-2α protein was detectable at 4 hours through recovery, time failed to influence expression. The degree of HIF-2α protein expression, however, was increased by hyperoxia, though only during recovery upon post-hoc analysis (Rec - RA: 0.70±0.14 vs. 1.53±0.25 arbitrary units, p<0.05; Fig 3B). The expression of VEGF mRNA derived by real-time PCR was not influenced by O2 concentration at any time point as determined by t-tests with Bonferroni's correction (Fig. 3C). The lack of a hyperoxia effect was not secondary to an inability to induce VEGF mRNA expression, as incubation with desferoximine for 24 hours yielded a 4-fold increase in VEGF mRNA.

Figure 3.

Effect of hyperoxia on HIF-1α or HIF-2α protein and VEGF mRNA expression. A. The immunoblot is representative of HIF-1α and HIF2-α protein expression in A549 cells following treatment with desferoximine or exposure to room air (RA) or 95% O2 (hyperoxia, Ox) for 4 hrs. B. Similar studies were conducted in cells exposed to RA or Ox at 24, 48 hrs, and 24 hrs Rec (+24 hrs). Histogram illustrates the effect of RA and Ox on HIF-2α protein expression corrected to β-actin. Columns represent mean (n=3) and bars SEM. “*” signifies p<0.05 of control vs. hyperoxia during recovery (+24 hrs). C. Following exposure to RA or Ox, A549 cells were harvested, RNA collected, and real time PCR performed as described in MATERIALS AND METHODS. The figure displays fold change in VEGF mRNA expression from baseline (T0 = prior to exposure) (n=3). D. Representative gel showing VEGF189, VEGF165, VEGF121, β-actin mRNA transcripts derived by RT-PCR. Corresponding controls confirmed the presence and size of each isoform.

To exclude the possibility that post-transcriptional splicing increased expression of individual VEGF isoforms, we used RT-PCR to semi-quantitatively assess the levels of VEGF189, VEGF165, or VEGF121 mRNA. As illustrated in Figure 3D, under basal conditions, all three isoforms were detected, with VEGF165 and VEGF121 displaying greater abundance than VEGF189. When the A549 cells were exposed to hyperoxia, VEGF isoform mRNAs varied little from baseline or from RA cells.

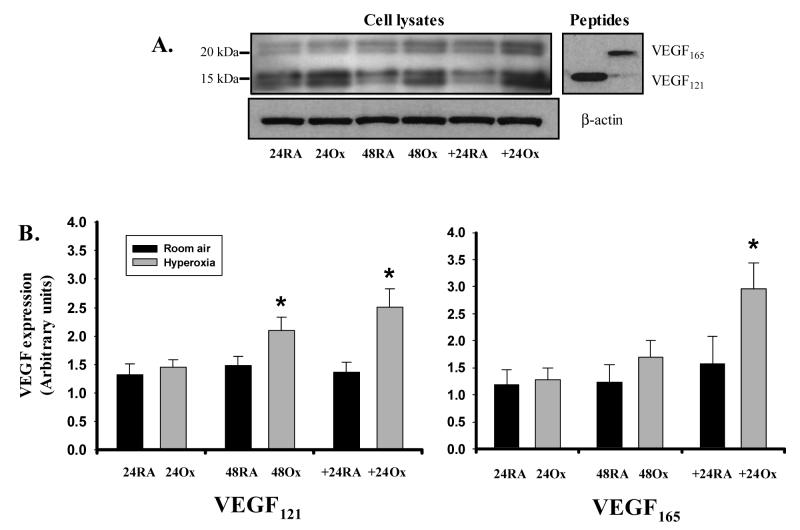

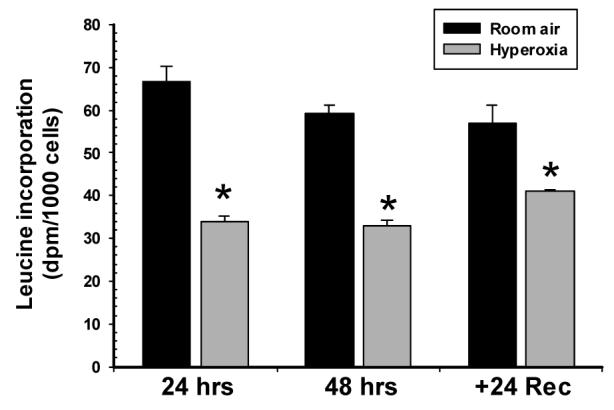

Hyperoxia increases the expression of cell-associated VEGF proteins

After finding a lack of transcriptional regulation, we next sought to assess the translational processes involved in VEGF production. As an initial measure, we studied the impact of hyperoxia on global translation, by the measuring the incorporation of [3H]leucine into protein. We found that hyperoxia decreased global protein synthesis by 49%, 44%, and 28%, at 24 and 48 hours of exposure, and 24 hours of recovery, respectively (Fig 4). Due to the heparin and heparan sulfate binding capacity of VEGF, cell lysates generally represent intracellular and ECM-bound isoforms. Using an antibody that recognizes VEGF121, VEGF165, and VEGF189, we observed doublet bands separating at approximately 18 and 22kD under reducing conditions (Fig 5A). The migration of these bands was analogous to that of VEGF121 and VEGF165 protein monomers run as controls. Although not formally delineated, the doublets are likely to represent glycosylation of the individual monomers. Analysis of variance demonstrated that both time and hyperoxia increased VEGF165 and VEGF121 protein expression in A549 cells (p<0.05), but there was no interaction between these variables. Individual differences between RA and Ox cells were noted at 48 hrs and recovery for VEGF121 and only during recovery for VEGF165 (Fig 5B).

Figure 4.

Hyperoxia decreases global protein synthesis in A549 cells. A549 cells were incubated with [3H]leucine during the final hour of each 24-hr period. Incorporation of label into protein was then determined on acid-insoluble extracts as described in MATERIALS AND METHODS. Results were expressed as dpm/1000 cells. Columns represent mean (n=4) and bars standard error of the mean. *Denotes p<0.05 between Room air and hyperoxia groups at same time point.

Figure 5.

Hyperoxia increases the expression of cell-associated VEGF protein. A. Representative immunoblots illustrating the impact of hyperoxia on VEGF protein expression in A549 cells. Right blot shows migration pattern of full-length VEGF121 and VEGF165 peptides under identical reducing conditions. B. Histograms illustrating the effect of room air (RA) and hyperoxia (Ox) on VEGF121 and VEGF165 protein expression. Expression was assessed at 24 and 48 hrs of exposure, and following recovery for 24 hrs in room air (+24). Columns represent mean (n=6) and bars standard error of the mean. *Denotes p<0.05 of hyperoxia vs. room air at a given time point.

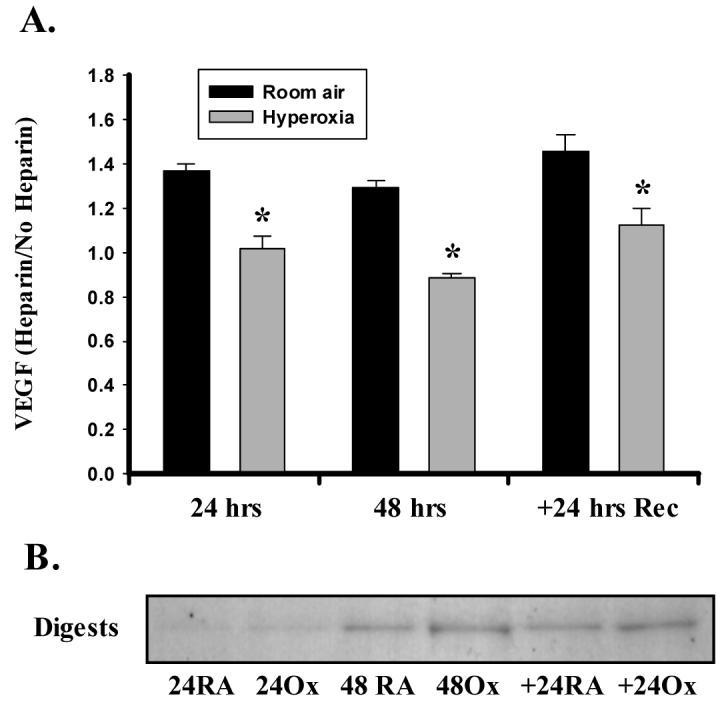

Hyperoxia alters VEGF binding

Cell membrane and ECM-associated VEGF constitutes a significant reserve of potentially releasable VEGF, particularly VEGF165. To determine if hyperoxia alters bound VEGF pools, we incubated cell monolayers with sodium heparin prior to exposure to hyperoxia. This approach illustrated an effect of both time and hyperoxia on medium-derived VEGF (but no interaction). Specifically, we observed 30-40% more medium-derived VEGF in RA cells compared to Ox cells at each 24-hour time point (Fig 6A). Since VEGF121 does not possess heparin-binding capacity, the observed increases are likely to represent VEGF165 as the capture antibody does not bind larger VEGF species. We also digested heparin-bound VEGF from cells following exposure using heparinase III. Western blotting of volume-reduced digests demonstrated the presence of a single VEGF isoform. Curiously, this band was enhanced in cells treated with hyperoxia at 48 hours and 24 hours Rec. The combined results from these two experiments suggest that hyperoxia alters the concentration of membrane and/or ECM-bound VEGF.

Figure 6.

Hyperoxia alters the binding of VEGF to heparin/heparan sulfate moieties. A. A549 cells were exposed to hyperoxia or room air in the presence or absence of 10 μg/ml of sodium heparin. Following the exposure period, medium was removed and assayed for the presence of VEGF by ELISA. Values are expressed as a ratio of medium + heparin/medium alone. Heparin increased soluble VEGF content at each time in room air (RA) but not in hyperoxia (Ox) cells. Columns represent mean (n=3) and bars standard error of the mean. *Denotes p<0.05 of Ox vs. RA at each time point. B. Representative immunoblot showing VEGF protein digested from cells with Heparinase III. Expression was assessed at 24 and 48 hrs of exposure, and following recovery for 24 hrs in room air (+24). Digests were prepared by adjusting Heparinase III concentration to cell number as described in MATERIALS AND METHODS.

DISCUSSION

Coordinated temporal and spatial expression of lung VEGF is crucial for the successful development of endothelial and epithelial cells into functional gas exchange units [23]. Aberrant VEGF expression leads to lung dysmorphogenesis, producing poor septal formation and a generalized emphysematous architecture [24, 25]. Beginning in the saccular phase of lung development, increasing amounts of VEGF are detected within the lung parenchyma [25]. Delivery prior to term has the potential to diminish parenchymal VEGF expression and signaling through the introduction of heightened oxidant stress to the alveolar epithelium. VEGF secreted into alveolar lining fluid increases steadily from birth through the first week of life in preterm infants [26]. Concentrations of ELF VEGF are inversely correlated to gestational age, with preterm infants possessing levels 4-fold greater than term infants [18, 27]. Because transition from the intrauterine to extrauterine environment obligates exposure to “relative” hyperoxia, enhanced ELF VEGF could represent a direct effect of the change in ambient O2 concentration. Exposure of newborn rabbits and 10-day-piglets to >95% O2 results in increased lung lavage VEGF-A concentrations within 4-5 days of exposure [6, 10]. In adult rabbits, the response is more rapid and short-lived, occurring within the first 24 hours of exposure [10]. The results presented herein confirm the ability of hyperoxia to enhance VEGF secretion in cell culture and suggest that post-transcriptional events contribute to this process.

Exposure of adult and newborn animals to hyperoxia is consistently reported to diminish VEGF mRNA within the lung, making the paradoxical rise of VEGF protein within lavage fluid somewhat of an enigma [6, 10, 28]. Further complicating the VEGF story is the rapid activation of extracellular-regulated kinases 1/2, c-jun N-terminal kinase, and p38 MAPK by hyperoxia [29]. Stimulation of these would be expected to prevent HIF ubiquitination, thereby stimulating VEGF transcription. In the current study, we found that incubation of A549 cells in 95% O2 fails to alter HIF-1α protein expression at 4 hours and beyond, but increases HIF-2α during recovery only. These outcomes are consistent with those recently reported by Asikainen and colleagues, demonstrating that exposure of A549 cells to 24 hours of hyperoxia does not influence VEGF mRNA, HIF-1α, HIF-2α protein, or total cell-associated VEGF protein levels [30]. Augmented HIF-2α protein expression in the absence of changes in VEGF mRNA expression during recovery may indicate that HIF-2α accumulation is exclusively cytoplasmic. HIF-2α protein has been shown to escape oxygen-dependent degradation in immortalized mouse embryonal fibroblasts, leading to the progressive accumulation of cytoplasmic rather than nuclear HIF-2α [31]. Because our measurements of VEGF mRNA are likely to reflect “steady-state” levels, we cannot exclude the possibility that enhanced nuclear HIF-2α levels induced a transient augmentation of VEGF transcription. Nonetheless, HIF stabilization cannot account for the increases in VEGF121 observed at 48 hours of exposure. In total, therefore, interpretation of our findings does not support HIF stabilization as a major mechanism for the increases in cell-associated VEGF protein during hyperoxia.

Post-transcriptional modification of the native VEGF mRNA by alternate splicing could also influence the relative distribution of the expressed messages leading to selective upregulation of specific VEGF isoforms. In newborn rabbits, hyperoxia suppresses total VEGF mRNA expression but increases the proportion of VEGF121 expressed relative to VEGF189 and VEGF165 mRNA [10]. Similar findings have been reported in premature, non-human primates treated with oxygen and mechanical ventilation [32]. Transcripts corresponding to each of the major splice variants, VEGF189, VEGF165, and VEGF121, have been previously identified in A549 cells [33]. In the current study, exposure to hyperoxia failed to alter the expression of any isoforms over time or in comparison to cells grown in room air, demonstrating that alternate splicing cannot account for the increase in medium-derived VEGF.

The lack of transcriptional activation led us to investigate translational and post-translational mechanisms for the increase in secreted VEGF. Angiotensin II (ANG II) has been documented to augment VEGF protein expression without altering mRNA levels or mRNA stability via a mechanism involving reactive oxygen species and cap-dependent translation [34, 35]. During exposure to hyperoxia, however, both global protein synthesis and cap-dependent translation are depressed [22]. Despite this, VEGF protein expression could be enhanced by a cap-independent mechanism involving either the AUG 1039 or CUG 499 start codons regulated by two IRES elements located in the 5'-UTR [36]. Bornes and colleagues have recently reported that tertiary interactions in mature VEGF mRNA regulate IRES activity and translational efficiency of individual VEGF isoform mRNAs [36]. In this manner, modulation of IRES activity could rapidly switch VEGF translation to favor specific isoforms in the absence of increased transcription or cap-dependent translation. The observation that hyperoxia enhances VEGF121 and VEGF165 proteins in the absence of increased mRNA is consistent with such a mechanism.

To determine if hyperoxia displaced VEGF from binding sites, we studied cells pre-incubated with 10 μg/ml of sodium heparin. This concentration has been shown to decrease the binding of 125I-VEGF to endogenous and transfected VEGF receptor 2 (VEGFR2/KDR) [37]. We found that exogenous heparin increased medium-derived VEGF from cells grown in room air, but not in those exposed to hyperoxia. Treatment of cells with heparinase to dissociate VEGF from heparin/heparan sulfate-binding sites revealed a reserve of VEGF in the hyperoxia-treated cells. As A549 cells are known to express both VEGFR1 and VEGFR2 protein, the results of the present study could reflect a shift in VEGF binding from receptors to heparin moieties [38]. Indeed hyperoxia has been shown to reduce VEGFR1 and VEGFR2 expression in the lungs of rats [39]. Given that hyperoxia also has the potential to alter heparin sulfate synthesis and ECM turnover, direct measurements of VEGF receptor expression and VEGF binding affinity will be required to clarify the current findings.

In addition to the increased expression of VEGF121 and VEGF165 proteins, changes in the proteolytic activity of the cellular microenvironment could also participate in the increase in secreted VEGF. Plasmin is known to cleave VEGF to yield VEGF110 and the anti-angiogenic isoform, VEGF165b [40]. Plasmin activity is regulated by urokinase-type plasminogen activator (uPA) and plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 (PAI-1). Hyperoxia has been reported to decrease uPA in airway epithelial cells and to increase PAI-1 in retinal pigment epithelial cells, effects that would diminish plasmin activity [41, 42]. Indeed a recent report found increased PAI-1/uPA ratios in premature infants with respiratory distress syndrome who were treated with O2 [43]. Hence increases in secreted VEGF could be explained by a reduction in VEGF clearance. Alternatively, cleavage of ECM-bound VEGF by matrix metalloproteinases could generate soluble, biologically-active, VEGF isoforms distinct from those transcribed [44]. Such isoforms may go undetected by the ELISA yet still contribute significantly to the pathophysiology. Thus although our findings strongly suggest that hyperoxia increases VEGF121 and VEGF165 secretion, we cannot exclude the presence of additional VEGF isoforms within the medium.

Lastly, we must concede that the present study has limitations. First, A549 cells, while used extensively throughout the literature to model alveolar epithelial cells, are a cancerous cell line incapable of making functional surfactant. Hence their response to hyperoxia may not accurately portray that of human type II cells. Furthermore, enhanced VEGF protein in lavage fluid is derived primarily from experimental models where O2 is delivered to induce lung injury in an otherwise normal lung. Although similar inspired O2 concentrations are used to treat patients, the goal is to restore physiologic arterial O2 tensions, not to exceed them.

Nevertheless, confirmation that hyperoxia increases secreted VEGF may have important clinical implications. For the oxygen-exposed preterm newborn, augmentation of specific isoforms of VEGF in lung fluid may promote lung growth thereby reducing the severity of alveolar and microvascular underdevelopment seen in BPD [7, 45]. Alternatively, isoform-specific increases in VEGF in lung lining fluid may augment alveolar-capillary permeability generating pulmonary edema common to the pathology both RDS and ALI [45, 46]. Additional studies will be needed to delineate the relative contributions of VEGF121/165 in a given clinical situation and to decipher their respective roles of each isoform to lung protection and injury.

Acknowledgments

This work is supported by grants from the Hearst Foundation of Dartmouth-Hitchcock Medical Center (JSS) and from the National Institutes of Health Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (JSS).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- 1.Voelkel NF, Vandivier RW, Tuder RM. Vascular endothelial growth factor in the lung. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2006;290:L209–221. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00185.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tischer E, Mitchell R, Hartman T, Silva M, Gospodarowicz D, Fiddes JC, Abraham JA. The human gene for vascular endothelial growth factor. Multiple protein forms are encoded through alternative exon splicing. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:11947–11954. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lee JW, Bae SH, Jeong JW, Kim SH, Kim KW. Hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF-1)alpha: its protein stability and biological functions. Exp Mol Med. 2004;36:1–12. doi: 10.1038/emm.2004.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Akiri G, Nahari D, Finkelstein Y, Le SY, Elroy-Stein O, Levi BZ. Regulation of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) expression is mediated by internal initiation of translation and alternative initiation of transcription. Oncogene. 1998;17:227–236. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1202019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Keyt BA, Berleau LT, Nguyen HV, Chen H, Heinsohn H, Vandlen R, Ferrara N. The carboxyl-terminal domain (111-165) of vascular endothelial growth factor is critical for its mitogenic potency. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:7788–7795. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.13.7788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ekekezie II, Thibeault DW, Rezaiekhaligh MH, Norberg M, Mabry S, Zhang X, Truog WE. Endostatin and vascular endothelial cell growth factor (VEGF) in piglet lungs: effect of inhaled nitric oxide and hyperoxia. Pediatr Res. 2003;53:440–446. doi: 10.1203/01.PDR.0000050121.70693.1A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Maniscalco WM, Watkins RH, Roper JM, Staversky R, O'Reilly MA. Hyperoxic ventilated premature baboons have increased p53, oxidant DNA damage and decreased VEGF expression. Pediatr Res. 2005;58:549–556. doi: 10.1203/01.pdr.0000176923.79584.f7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Klekamp JG, Jarzecka K, Perkett EA. Exposure to hyperoxia decreases the expression of vascular endothelial growth factor and its receptors in adult rat lungs. Am J Pathol. 1999;154:823–831. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)65329-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yee M, Vitiello PF, Roper JM, Staversky RJ, Wright TW, McGrath-Morrow SA, Maniscalco WM, Finkelstein JN, O'Reilly MA. Type II epithelial cells are critical target for hyperoxia-mediated impairment of postnatal lung development. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2006;291:L1101–1111. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00126.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Watkins RH, D'Angio CT, Ryan RM, Patel A, Maniscalco WM. Differential expression of VEGF mRNA splice variants in newborn and adult hyperoxic lung injury. Am J Physiol. 1999;276:L858–867. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1999.276.5.L858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kaner RJ, Ladetto JV, Singh R, Fukuda N, Matthay MA, Crystal RG. Lung overexpression of the vascular endothelial growth factor gene induces pulmonary edema. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2000;22:657–664. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb.22.6.3779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Le Cras TD, Spitzmiller RE, Albertine KH, Greenberg JM, Whitsett JA, Akeson AL. VEGF causes pulmonary hemorrhage, hemosiderosis, and air space enlargement in neonatal mice. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2004;287:L134–142. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00050.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gupta K, Kshirsagar S, Li W, Gui L, Ramakrishnan S, Gupta P, Law PY, Hebbel RP. VEGF prevents apoptosis of human microvascular endothelial cells via opposing effects on MAPK/ERK and SAPK/JNK signaling. Exp Cell Res. 1999;247:495–504. doi: 10.1006/excr.1998.4359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Perkins GD, Roberts J, McAuley DF, Armstrong L, Millar A, Gao F, Thickett DR. Regulation of vascular endothelial growth factor bioactivity in patients with acute lung injury. Thorax. 2005;60:153–158. doi: 10.1136/thx.2004.027912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Thickett DR, Armstrong L, Millar AB. A role for vascular endothelial growth factor in acute and resolving lung injury. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2002;166:1332–1337. doi: 10.1164/rccm.2105057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kumar VH, Lakshminrusimha S, El Abiad MT, Chess PR, Ryan RM. Growth factors in lung development. Adv Clin Chem. 2005;40:261–316. doi: 10.1016/s0065-2423(05)40007-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bhatt AJ, Pryhuber GS, Huyck H, Watkins RH, Metlay LA, Maniscalco WM. Disrupted pulmonary vasculature and decreased vascular endothelial growth factor, Flt-1, and TIE-2 in human infants dying with bronchopulmonary dysplasia. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001;164:1971–1980. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.164.10.2101140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.D'Angio CT, Maniscalco WM, Ryan RM, Avissar NE, Basavegowda K, Sinkin RA. Vascular endothelial growth factor in pulmonary lavage fluid from premature infants: effects of age and postnatal dexamethasone. Biol Neonate. 1999;76:266–273. doi: 10.1159/000014168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang X, Ryter SW, Dai C, Tang ZL, Watkins SC, Yin XM, Song R, Choi AM. Necrotic cell death in response to oxidant stress involves the activation of the apoptogenic caspase-8/bid pathway. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:29184–29191. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M301624200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ollivier V, Bentolila S, Chabbat J, Hakim J, de Prost D. Tissue factor-dependent vascular endothelial growth factor production by human fibroblasts in response to activated factor VII. Blood. 1998;91:2698–2703. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kobayashi T, Liu X, Wen FQ, Fang Q, Abe S, Wang XQ, Hashimoto M, Shen L, Kawasaki S, Kim HJ, Kohyama T, Rennard SI. Smad3 mediates TGF-beta1 induction of VEGF production in lung fibroblasts. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2005;327:393–398. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.12.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shenberger JS, Myers JL, Zimmer SG, Powell RJ, Barchowsky A. Hyperoxia alters the expression and phosphorylation of multiple factors regulating translation initiation. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2005;288:L442–449. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00127.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Akeson AL, Greenberg JM, Cameron JE, Thompson FY, Brooks SK, Wiginton D, Whitsett JA. Temporal and spatial regulation of VEGF-A controls vascular patterning in the embryonic lung. Dev Biol. 2003;264:443–455. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2003.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gerber HP, Hillan KJ, Ryan AM, Kowalski J, Keller GA, Rangell L, Wright BD, Radtke F, Aguet M, Ferrara N. VEGF is required for growth and survival in neonatal mice. Development. 1999;126:1149–1159. doi: 10.1242/dev.126.6.1149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Grover TR, Parker TA, Zenge JP, Markham NE, Kinsella JP, Abman SH. Intrauterine hypertension decreases lung VEGF expression and VEGF inhibition causes pulmonary hypertension in the ovine fetus. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2003;284:L508–517. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00135.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lassus P, Ristimaki A, Ylikorkala O, Viinikka L, Andersson S. Vascular endothelial growth factor in human preterm lung. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1999;159:1429–1433. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.159.5.9806073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lassus P, Turanlahti M, Heikkila P, Andersson LC, Nupponen I, Sarnesto A, Andersson S. Pulmonary vascular endothelial growth factor and Flt-1 in fetuses, in acute and chronic lung disease, and in persistent pulmonary hypertension of the newborn. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001;164:1981–1987. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.164.10.2012036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Maniscalco WM, Watkins RH, D'Angio CT, Ryan RM. Hyperoxic injury decreases alveolar epithelial cell expression of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) in neonatal rabbit lung. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 1997;16:557–567. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb.16.5.9160838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Berra E, Pages G, Pouyssegur J. MAP kinases and hypoxia in the control of VEGF expression. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2000;19:139–145. doi: 10.1023/a:1026506011458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Asikainen TM, Schneider BK, Waleh NS, Clyman RI, Ho WB, Flippin LA, Gunzler V, White CW. Activation of hypoxia-inducible factors in hyperoxia through prolyl 4-hydroxylase blockade in cells and explants of primate lung. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:10212–10217. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0504520102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Park SK, Dadak AM, Haase VH, Fontana L, Giaccia AJ, Johnson RS. Hypoxia-induced gene expression occurs solely through the action of hypoxia-inducible factor 1alpha (HIF-1alpha): role of cytoplasmic trapping of HIF-2alpha. Mol Cell Biol. 2003;23:4959–4971. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.14.4959-4971.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tambunting F, Beharry KD, Waltzman J, Modanlou HD. Impaired lung vascular endothelial growth factor in extremely premature baboons developing bronchopulmonary dysplasia/chronic lung disease. J Investig Med. 2005;53:253–262. doi: 10.2310/6650.2005.53508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Boussat S, Eddahibi S, Coste A, Fataccioli V, Gouge M, Housset B, Adnot S, Maitre B. Expression and regulation of vascular endothelial growth factor in human pulmonary epithelial cells. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2000;279:L371–378. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.2000.279.2.L371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Feliers D, Duraisamy S, Barnes JL, Ghosh-Choudhury G, Kasinath BS. Translational regulation of vascular endothelial growth factor expression in renal epithelial cells by angiotensin II. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2005;288:F521–529. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00271.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Feliers D, Gorin Y, Ghosh-Choudhury G, Abboud HE, Kasinath BS. Angiotensin II stimulation of VEGF mRNA translation requires production of reactive oxygen species. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2006;290:F927–936. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00331.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bornes S, Boulard M, Hieblot C, Zanibellato C, Iacovoni JS, Prats H, Touriol C. Control of the vascular endothelial growth factor internal ribosome entry site (IRES) activity and translation initiation by alternatively spliced coding sequences. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:18717–18726. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M308410200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tessler S, Rockwell P, Hicklin D, Cohen T, Levi BZ, Witte L, Lemischka IR, Neufeld G. Heparin modulates the interaction of VEGF165 with soluble and cell associated flk-1 receptors. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:12456–12461. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wang XF, Tu LF, Wang LH, Zhou JY. Inhibition of expression of vascular endothelial growth factor and its receptors in pulmonary adenocarcinoma cell by TNP-470 in combination with gemcitabine. J Zhejiang Univ Sci B. 2006;7:837–843. doi: 10.1631/jzus.2006.B0837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hosford GE, Olson DM. Effects of hyperoxia on VEGF, its receptors, and HIF-2alpha in the newborn rat lung. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2003;285:L161–168. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00285.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bates DO, Cui TG, Doughty JM, Winkler M, Sugiono M, Shields JD, Peat D, Gillatt D, Harper SJ. VEGF165b, an inhibitory splice variant of vascular endothelial growth factor, is down-regulated in renal cell carcinoma. Cancer Res. 2002;62:4123–4131. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Buckley S, Warburton D. Dynamics of metalloproteinase-2 and -9, TGF-beta, and uPA activities during normoxic vs. hyperoxic alveolarization. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2002;283:L747–754. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00415.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Erichsen JT, Jarvis-Evans J, Khaliq A, Boulton M. Oxygen modulates the release of urokinase and plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 by retinal pigment epithelial cells. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2001;33:237–247. doi: 10.1016/s1357-2725(01)00009-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cederqvist K, Siren V, Petaja J, Vaheri A, Haglund C, Andersson S. High concentrations of plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 in lungs of preterm infants with respiratory distress syndrome. Pediatrics. 2006;117:1226–1234. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-0870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lee S, Jilani SM, Nikolova GV, Carpizo D, Iruela-Arispe ML. Processing of VEGF-A by matrix metalloproteinases regulates bioavailability and vascular patterning in tumors. J Cell Biol. 2005;169:681–691. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200409115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kunig AM, Balasubramaniam V, Markham NE, Seedorf G, Gien J, Abman SH. Recombinant human VEGF treatment transiently increases lung edema but enhances lung structure after neonatal hyperoxia. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2006;291:L1068–1078. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00093.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Compernolle V, Brusselmans K, Acker T, Hoet P, Tjwa M, Beck H, Plaisance S, Dor Y, Keshet E, Lupu F, Nemery B, Dewerchin M, Van Veldhoven P, Plate K, Moons L, Collen D, Carmeliet P. Loss of HIF-2alpha and inhibition of VEGF impair fetal lung maturation, whereas treatment with VEGF prevents fatal respiratory distress in premature mice. Nat Med. 2002;8:702–710. doi: 10.1038/nm721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]