Abstract

Felbamate (FBM) is a potent nonsedative anticonvulsant whose clinical effect is chiefly related to gating modification (and thus use-dependent inhibition) rather than pore block of N-methyl-d-aspartate (NMDA) channels at pH 7.4. Using whole-cell recording in rat hippocampal neurons, we examined the effect of extracellular pH on FBM action. In sharp contrast to the findings at pH 7.4, the inhibitory effect of FBM on NMDA currents shows much weakened use-dependence at pH 8.4. Moreover, FBM neither accelerates the activation kinetics of the NMDA channel, nor enhances the currents elicited by very low concentrations of NMDA at pH 8.4. These differential effects of FBM between pH 7.4 and 8.4 are abolished in the mutant NMDA channels which lack proton sensitivity. Most interestingly, the inhibitory effect of FBM becomes flow-dependent and is evidently stronger in inward than in outward NMDA currents at pH 8.4. These findings indicate that FBM has a significantly more manifest pore-blocking effect on the NMDA channel at pH 8.4 than at pH 7.4. FBM therefore acts as an opportunistic pore blocker modulated by extracellular proton, suggesting that the FBM binding site is located at the junction of a widened and a narrow part of the ion conduction pathway. Also, we find that the inhibitory effect of FBM on NMDA currents is antagonized by external but not internal Na+, and that increase of external Na+ decreases the binding rate without altering the unbinding rate of FBM. These findings indicate that the FBM binding site faces the extracellular rather than the intracellular solution, and coincides with the outmost ionic (e.g., Na+) site in the NMDA channel pore. We conclude that the FBM binding site very likely is located in the external pore mouth, where extracellular proton, Na+, FBM, and NMDA channel gating have an orchestrating effect.

INTRODUCTION

N-Methyl-d-aspartate (NMDA) channel antagonists have been found to show a broad-spectrum antiepileptic effect on experimental seizure models (1). Although the anticonvulsant activity of NMDA channel antagonists has generated considerable interest, in clinical trials most NMDA channel antagonists have demonstrated serious neurobehavioral complications that have limited their further pharmaceutical development (2,3). Up to now, the only approved anticonvulsant that exhibits NMDA channel inhibitory activity at therapeutic concentrations is felbamate (FBM; 2-phenyl-1,3-propanediol dicarbamate) (4–7). Although side effects such as aplastic anemia and hepatotoxicity have limited its use as a first-line agent, FBM has remained as a useful anticonvulsant for Lennox-Gastaut syndrome in children and for a variety of complex partial seizures that are refractory to the other anticonvulsants in adults (for a review, see (8–10)).

We have shown that FBM has a higher affinity to the open and especially the desensitized NMDA channels (dissociation constants ∼110 and ∼55 μM, respectively) than to the closed channels (dissociation constant ∼200 μM) (5). Also, FBM delays the recovery from desensitization in the NMDA channel. Although the differences between the binding affinity is not large, the selective binding of FBM to the open and especially to the desensitized channels well explains, both qualitatively and quantitatively, the enhancement of NMDA currents in low concentrations (≤10 μM) of NMDA and the (use-dependent) inhibition of NMDA currents in high concentrations (≥30 μM) of NMDA (5,11). Submillimolar FBM thus is an effective gating modifier rather than a pore blocker of the NMDA channel at pH 7.4. The gating-modification actions of FBM are similar to ifenprodil (a phenylethanolamine), which also enhances NMDA currents when the NMDA concentration is extremely low (e.g., 0.3–1 μM) but has a dose-dependent inhibitory effect in higher concentrations of NMDA (12–14). It seems that FBM and ifenprodil, albeit structurally different, both favor the conformational changes induced by NMDA on NMDA channels, namely activation and desensitization. It has been shown that the high-affinity binding site of ifenprodil is located in the amino terminal domain of NR2B subunit (12,15). Interestingly, FBM also has a stronger effect on NMDA channels containing NR2B than those containing NR2A or NR2C subunit (4,16). However, Kleckner et al. found that mutations in the amino terminal of NR2B subunit may significantly affect ifenprodil but not FBM binding (4). The molecular and functional location of the FBM binding site thus remains largely unclear.

Nanomolar extracellular proton is a well-known gating modifier of the NMDA channel. The modification is so strong that there could be a tonic inhibition of NMDA currents by ∼50% at physiological pH (17–20). Extracellular proton may also interact with the other gating modifiers of the channel. For example, the inhibitory effect of ifenprodil on NMDA currents is strongly dependent on extracellular proton, and there is a 30-fold increase of the IC50 value with a change of pH from 8.5 to 7.0 ((21); see also (14)). It would therefore be interesting to see whether there are also interactions between extracellular proton and FBM, which has a similar gating-modification effect to ifenprodil. In this study, we demonstrate that in contrast to the case at pH 7.4, FBM shows evident features of a pore blocker of the NMDA channel at pH 8.4. Also, the inhibitory effect of FBM on NMDA currents is antagonized by external but not internal Na+. FBM thus is an opportunistic pore blocker of the NMDA channel with its binding site located at a pore region of critical dimensions, most likely the junction of a widened and a narrow part in the external vestibule of the channel pore. These findings may indicate extracellular pH-sensitive as well as functionally important gating conformational changes at this pore region.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Dissociated neuron preparation

Coronal slices of the whole brain were prepared from 7- to 14-day-old Wistar rats. Hippocampal CA1 region was dissected from the slices and cut into small chunks. Tissue chunks were treated with 1 mg/ml protease XXIII (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) in dissociation medium (82 mM Na2SO4, 30 mM K2SO4, 3 mM MgCl2, and 5 mM HEPES, pH 7.4) for 3–5 min at 35°C, and then were moved into dissociation medium containing no protease but 1 mg/ml bovine serum albumin (Sigma). Each time two to three chunks were picked and triturated to release single neurons for whole-cell recordings.

Whole-cell recordings

The dissociated neurons were put in a recording chamber containing Tyrode's solution (150 mM NaCl, 4 mM KCl, 2 mM MgCl2, 2 mM CaCl2, and 10 mM HEPES, pH 7.4). Whole-cell voltage-clamp recordings were obtained using fire-polished pipettes pulled from borosilicate capillaries (outer diameter, 1.55–1.60 mm; Hilgenberg, Malsfeld, Germany). Except for the internal FBM experiments in Fig. 6 and the experiments of different concentrations of internal Na+ in Figs. 5 C and 8 B, the pipettes were filled with the standard (150 mM Na+) internal solution containing 75 mM NaCl, 75 mM NaF, 10 mM HEPES, and 5 mM EGTA, with pH adjusted to 7.4 by NaOH. For the experiments studying the effect of internal FBM in Fig. 6, 1 mM FBM was added to the standard internal solution. In Figs. 5 C and 8 B, the internal solutions of 300 and 450 mM Na+ contained the same components as the standard internal solution, except that 75 mM NaCl was replaced by 225 and 375 mM NaCl, respectively. The internal solution of 75 mM Na+ contained 40 mM NaCl, 35 mM NaF, 10 mM HEPES, and 5 mM EGTA. A seal was formed, and the whole-cell configuration was obtained in Tyrode's solution. The cell was then lifted from the bottom of the chamber and moved in front of a set of Square glass, three-barrel tubes (0.6 mm internal diameter) or Theta glass tubes (2.0 mm outer diameter pulled to an opening of ∼300 μm in width; Warner Instrument, Hamden, CT) emitting either control or FBM-containing external recording solutions. Except for the experiments of different concentrations of external Na+ in Figs. 5, A and B, 7, C and D, and 8 A, the standard external solution was Mg2+-free Tyrode's solution (pH 7.4 or 8.4). In Figs. 5, A and B, 7, C and D, and 8 A, the external Na+ concentration was changed from 25 to 750 mM with the same other components as the Mg2+-free Tyrode's solution. Different amounts of sucrose were added into the solution on the opposite side to maintain roughly the same osmolarity on both sides of the membrane and reduce the likelihood of losing a tight seal. All external solutions contained 0.5 μM tetrodotoxin to block the sodium currents. The glass-tube holder was connected to a stepper motor (SF-77B perfusion system, Warner Instrument) to achieve fast switch between different tubes and therefore rapid solution change. The rate of solution change was assessed by the method described previously (5). In short, the rate of change in current size between two different external solutions, namely Tyrode's solution and a solution containing 150 mM N-methyl-d-glucamine instead of 150 mM Na+. The 50% current change time is ∼6 ms and ∼40 ms for the Theta glass and the Square glass, respectively (5). Theta glass tubes were therefore used in the experiments investigating the effect of FBM on the kinetics of channel gating in Figs. 2 and 7, where a better resolution in the time domain is required. In the other experiments, Square glass tubes were used because a larger number of different kinds of external solutions can be loaded at the same time. FBM (Tocris Cookson, Bristol, UK) was dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide as well as NMDA and glycine (Sigma) were dissolved in water to make 100, 100, and 10 mM stock solutions, respectively. The stock solutions were then diluted into Mg2+-free Tyrode's solution to attain the final concentrations desired (10 μM to 1 mM FBM, 6 μM or 1 mM NMDA, 0.3 μM glycine). The final concentration of dimethyl sulfoxide (≤1%) was found to have no detectable effect on NMDA currents. The highest FBM concentration used in this study was ∼3 mM, which is roughly the maximal solubility of the drug in water, and was made by dissolving FBM directly into Mg2+-free Tyrode's solution right before the experiment. However, 300 μM was chosen as the most used FBM concentration in this study, because 300 μM is well within the solubility limit and also the therapeutic range (50–300 μM) of the drug. The cells were voltage-clamped at −70 mV unless otherwise specified. NMDA currents were recorded at room temperature (∼25°C) with an Axoclamp 200A amplifier, filtered at 1 kHz with a four-pole Bessel filter, digitized at 200- to 500-μs intervals, and stored using a Digidata-1322A analog/digital interface along with the pCLAMP software (all from Axon Instruments, Union City, CA). Data are expressed as mean ± SE. For comparisons between experimental groups, the Student's t-test was used and p < 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

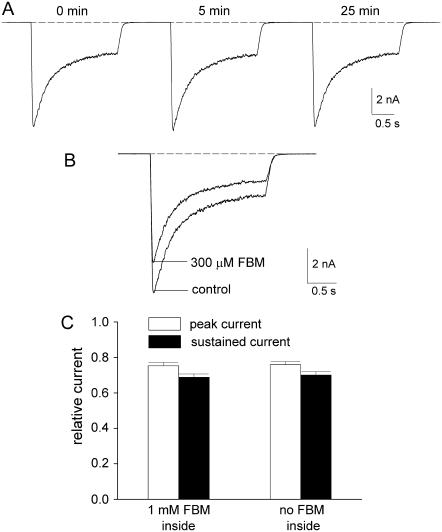

FIGURE 6.

Internal FBM has no inhibitory effect on NMDA currents. (A) Every 1 min, NMDA currents were recorded with the same experimental protocol as that in Fig. 1 A (at extracellular pH 8.4), but here the internal solution contained 1 mM FBM. The numbers above the sweeps indicate the recording time after establishment of the whole-cell configuration. Note the lack of significant reduction of the NMDA current throughout the experiment (up to ∼25 min). The dashed line indicates zero current level. (B) For comparison, 300 μM external FBM always significantly inhibits the NMDA current (the currents were also obtained 25 min after establishment of the whole-cell configuration). (C) With 1 mM internal FBM, the relative peak and sustained currents in 300 μM external FBM (normalized to that in zero external FBM) are 0.75 ± 0.02, and 0.68 ± 0.02, respectively (n = 5). For comparison, the relative peak and sustained currents with no FBM added to the inside are 0.76 ± 0.02, and 0.70 ± 0.02, respectively (data from Fig. 1 B).

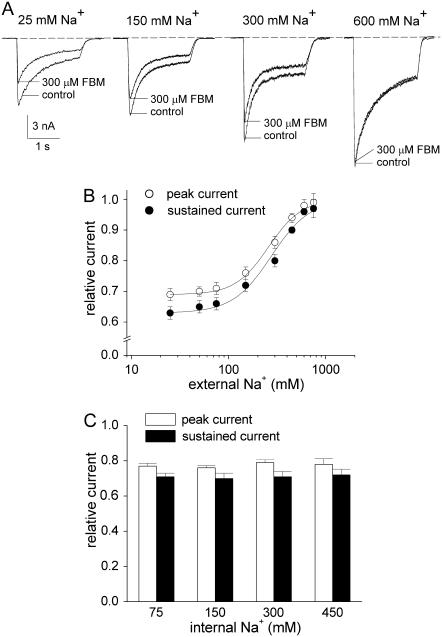

FIGURE 5.

The inhibitory effect of FBM on NMDA currents is dependent on external but not internal Na+ at pH 8.4. (A) NMDA currents were elicited by application of 1 mM NMDA and 0.3 μM glycine in the absence (control) and presence of 300 μM FBM. At extracellular pH 8.4, the internal Na+ was fixed at 150 mM, but the external Na+ was increased from 25 to 750 mM. It is evident that the inhibitory effects of FBM on both peak and sustained currents decrease with increased external Na+. The dashed line indicates zero current level. (B) Cumulative results are obtained from seven cells with the same experimental protocol described in panel A. The relative current is defined by the ratio between the amplitude of the currents elicited by 1 mM NMDA pulse in FBM-containing and FBM-free external solutions in the same cell, and is plotted against the concentration of external Na+. The lines are the best fits of the form: relative current = 0.69+(0.31/(1+(258/[Na+]))) and 0.63+(0.37/(1+(275/[Na+]))) for the peak and sustained currents, respectively (see Eq. 1 in Results, where [Na+] denotes the Na+ concentration in mM). (C) Cumulative results are obtained from 12 cells with the same experimental protocol described in panel A, but here the internal Na+ was increased from 75 to 450 mM with the external Na+ fixed at 150 mM. The relative peak currents are 0.77 ± 0.02, 0.76 ± 0.01, 0.79 ± 0.02, and 0.78 ± 0.03 for 75, 150, 300, and 450 mM internal Na+, respectively. The relative sustained currents are 0.71 ± 0.02, 0.70 ± 0.03, 0.71 ± 0.03, and 0.72 ± 0.03 for 75, 150, 300, and 450 mM internal Na+, respectively.

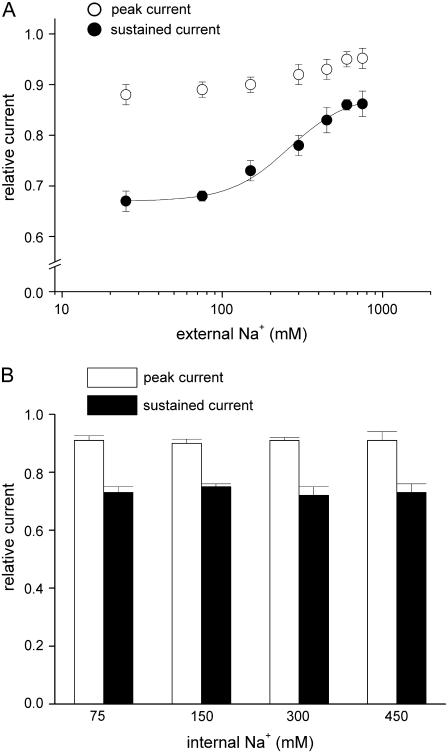

FIGURE 8.

The inhibitory effect of FBM on NMDA currents at pH 7.4 is also dependent on external but not internal Na+. (A) Cumulative results are obtained from five cells with the same experimental protocol described in Fig. 5 B, but here the extracellular pH was 7.4. The relative peak currents are 0.88 ± 0.02, 0.89 ± 0.01, 0.90 ± 0.01, 0.92 ± 0.02, 0.93 ± 0.02, 0.95 ± 0.01, and 0.95 ± 0.03 for 25, 75, 150, 300, 450, 600, and 750 mM external Na+, respectively. The relative sustained currents are 0.67 ± 0.02, 0.68 ± 0.01, 0.73 ± 0.02, 0.78 ± 0.02, 0.83 ± 0.03, 0.86 ± 0.01, and 0.86 ± 0.03 for 25, 75, 150, 300, 450, 600, and 750 mM external Na+, respectively. For the relative sustained currents, the line is the best fit of the form: relative current = 0.67+(0.21/(1+(262/[Na+]))), where [Na+] denotes the Na+ concentration in mM. (B) Cumulative results are obtained from 12 cells with the same experimental protocol described in Fig. 5 C, but here the extracellular pH was 7.4. The relative peak currents are 0.91 ± 0.02, 0.90 ± 0.01, 0.91 ± 0.01, and 0.91 ± 0.03 for 75, 150, 300, and 450 mM internal Na+, respectively. The relative sustained currents are 0.73 ± 0.02, 0.75 ± 0.01, 0.72 ± 0.03, and 0.73 ± 0.03 for 75, 150, 300, and 450 mM internal Na+, respectively.

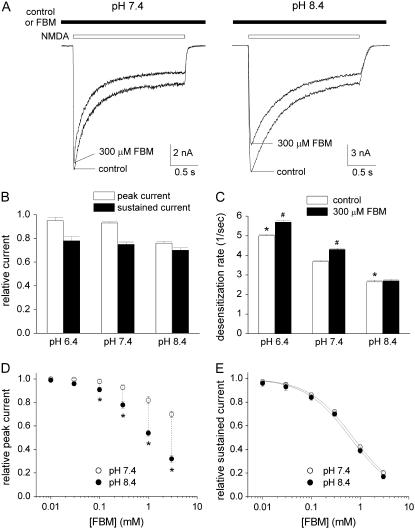

FIGURE 1.

The inhibitory effect of FBM on NMDA currents shows much weakened use-dependence at pH 8.4. (A) NMDA currents were elicited by application of 1 mM NMDA and 0.3 μM glycine in the absence (control) and presence of 300 μM FBM at different extracellular pH. If FBM was present in the external solution, it was present throughout the whole experiment (i.e., before, during, and after the NMDA pulse). FBM has only little inhibitory effect on the early peak current, but significantly inhibits the late sustained current at pH 7.4 (left panel). In contrast, FBM significantly inhibits both the early peak and late sustained currents at pH 8.4 (right panel). (B) Cumulative results are obtained from eight cells with the same experimental protocol described in panel A. The relative current is defined by the ratio between the amplitude of the currents elicited by the 1 mM NMDA pulse in FBM-containing and FBM-free external solutions in the same cell. For the peak currents, the relative currents are 0.95 ± 0.03, 0.93 ± 0.01, and 0.76 ± 0.02 for pH 6.4, 7.4, and 8.4, respectively. For the late currents, the relative currents are 0.78 ± 0.03, 0.75 ± 0.02, and 0.70 ± 0.02 for pH 6.4, 7.4, and 8.4, respectively. (C) The experimental protocol is similar to that described in panel A. The decay phase of the macroscopic NMDA currents is fitted with a single-exponential function, and the inverse of the time constant from the fit is defined as the desensitization rate (n = 8). *p < 0.05, compared with the control data at pH 7.4. #p < 0.05, compared with the control data at the same pH value. (D and E) The same experiment as that described in panel A was repeated in different concentrations of FBM (10 μM to 3 mM). The cumulative results of the relative current are plotted against the FBM concentration (n = 5). For the peak current, it is evident that the data at pH 8.4 are significantly smaller than those at pH 7.4 in 100 μM to 3 mM FBM (*p < 0.05) (D). For the sustained current, the two solid lines are the best fits to the mean data of pH 7.4 and 8.4 using the Hill equation (response = maximal response/(1+([FBM]/IC50)nH), where nH is the Hill coefficient). The best fits give calculated IC50 values of 0.71 and 0.64 mM FBM at pH 7.4 and 8.4, respectively (E).

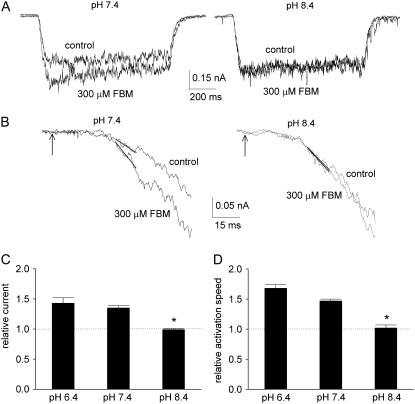

FIGURE 2.

FBM fails to accelerate the activation kinetics of NMDA currents at pH 8.4. (A) The cell was moved every 60 s from the NMDA- and glycine-free external solution to the external solution containing 6 μM NMDA and 0.3 μM glycine for 1 s, and then moved back to the NMDA-free external solution. FBM either was absent in both external solutions (the control sweep), or 300 μM FBM was added only to the NMDA-free but not the NMDA-containing external solutions (the 300 μM FBM sweep). The early NMDA current is evidently enhanced with the rising phase accelerated by FBM at pH 7.4, but FBM has only a negligible effect on the NMDA current at pH 8.4. (B) The rising phase of the currents in panel A is enlarged to demonstrate the accelerated channel activation in detail. The arrow indicates the time point at which the command of solution change is given electronically. The current between 35 and 45 ms from the arrow is fitted with a linear regression function to obtain the slope of current increase (in the unit of pA/ms). This time window is a deliberately chosen compromise, because it should be as late as possible to avoid incomplete solution change and the probable initial delay in channel activation (solution change should be complete within 30 ms of the electronic command with Theta glass tube, see Materials and Methods and (5)) but as early as possible to avoid contamination of channel desensitization. (C,D) Cumulative results are obtained from five cells with the same experimental protocol described in panels A and B. The relative early current is defined by the ratio between the amplitude of the currents (the average current from 100 to 150 ms after the beginning of the NMDA pulse) elicited by 6 μM NMDA pulse in the presence and absence of 300 μM FBM in the same cell. The relative currents are 1.43 ± 0.09, 1.35 ± 0.04, and 0.99 ± 0.02 for pH 6.4, 7.4, and 8.4, respectively (C). In each individual cell, the slope of current increase with 300 μM FBM is normalized to the slope in the control (FBM-free) condition to give the relative activation speed. The cumulative results of the relative activation speed from five cells are 1.68 ± 0.06, 1.47 ± 0.03, and 1.02 ± 0.05 for pH 6.4, 7.4, and 8.4, respectively (D). *p < 0.05, compared with the data at pH 7.4.

FIGURE 7.

The kinetics of FBM binding to the activated NMDA channel are linearly correlated with the FBM concentration at pH 8.4. (A) The kinetics of development of inhibition (left panel) and recovery from inhibition (right panel) of the steady-state inward NMDA (1 mM) currents were studied by fast application and removal of FBM with Theta glass tubes at extracellular pH 8.4. (Left) The decay phase of the current after application of FBM can be reasonably fitted with single-exponential functions, giving macroscopic binding time constants of 115 and 22 ms for 100 and 1000 μM FBM, respectively. (Right) The increment phase of the current after washoff of FBM can be reasonably fitted with single-exponential functions, giving unbinding time constants of 287 and 295 ms for 100 and 1000 μM FBM, respectively. To avoid the effect from incomplete solution change, the fitting range is carefully selected after a 10-ms delay in the decay or increment phase of the current trace. The dashed lines indicate zero current level. (B) Cumulative results are obtained from six cells with the experiments described in panel A. The binding and unbinding rates are obtained from the inverses of the foregoing time constants and plotted against the FBM concentration. The lines are linear regression fits to the mean values of the binding and unbinding rates, respectively. For the binding rates, the slope and intercept are 4.4 × 104 M−1 s−1 and 3.9 s−1, respectively. For the unbinding rates, the intercept is 3.7 s−1 and the slope is essentially zero (i.e., a horizontal line indicating that the unbinding rates are unrelated to the FBM concentration). (C,D) Cumulative results are obtained from eight cells with 300 μM FBM using the same experimental protocol described in panel A. Here the internal Na+ was fixed at 150 mM, but the external Na+ was increased from 50 to 450 mM. The binding rates are 26.9 ± 1.1, 20.0 ± 0.8, and 15.8 ± 0.6 s−1 for 50, 150, and 450 mM external Na+, respectively (C). The unbinding rates are 3.8 ± 0.3, 3.7 ± 0.2, and 3.9 ± 0.2 s−1 for 50, 150, and 450 mM external Na+, respectively (D). *p < 0.05, compared with the data of 150 mM external Na+.

Molecular biology

The rat cDNA clones of NMDA channels used in this study are the NR1a variant and the NR2B clone. The sequences of amino acid residues in the NR1 subunit are numbered from the initiator methionine as in the original article (22). Site-directed mutagenesis in the NR1 subunit was carried out using the QuikChange kit (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA). Mutations were verified by DNA sequencing, and two independent clones for each mutant were tested to preclude any inadvertent mutations. The full-length capped cRNA transcripts were then synthesized from each of NR1 and NR2B using T7 and T3 mMESSAGE mMACHINE transcription kits (Ambion, Austin, TX), respectively. Xenopus oocytes (stages V–VI) were injected with a mixture of NR1 and NR2 cRNAs in a ratio of 1:5 to minimize the probability of formation of homomeric NR1 receptors. Oocytes were then maintained in the culture medium (96 mM NaCl, 2 mM KCl, 1.8 mM MgCl2, 1.8 mM CaCl2, 5 mM HEPES, and 50 μg/ml gentamycin, pH 7.6) at 18°C for 2–3 days before intracellular recordings.

Intracellular recordings

Oocytes were placed in a small working-volume (<20 μl) perfusion chamber (OPC-1, AutoMate Scientific, San Francisco, CA) that is optimized for fast solution exchange. The NMDA currents were recorded at room temperature (∼25°C) with two-electrode voltage clamp (OC-725C amplifier; Warner Instrument). The microelectrodes, pulled from borosilicate capillaries and filled with 1 M KCl, had resistances of 0.5–4 MΩ. Oocytes were voltage-clamped at −70 mV and continuously perfused with Mg2+-free ND 96 solution (96 mM NaCl, 2 mM KCl, 0.3 mM BaCl2, and 5 mM HEPES, pH 7.4 or 8.4). Data were acquired using the Digidata-1322A analog/digital interface with pCLAMP software (Axon Instruments). The sampling rates were 0.5–1 kHz, and all statistics are given as mean ± SE.

RESULTS

FBM may act as a pore blocker of the NMDA channel at extracellular pH 8.4

Fig. 1, A and B, shows that FBM has only little inhibitory effect on the early peak NMDA current but significantly inhibits the late sustained current at pH 7.4 and 6.4. In these conditions, the inhibitory effect of FBM on NMDA currents is stronger with longer exposure to NMDA, a feature indicative of use-dependent inhibition (see also (5)). In contrast, FBM significantly inhibits both the early peak and late sustained NMDA currents at pH 8.4, suggesting loss of use-dependence of FBM action at more alkaline external milieu. On the other hand, the desensitization kinetics of the channel seems to get slower when extracellular pH becomes more alkaline whether FBM is present or not (Fig. 1, A and C), consistent with the idea that the external proton itself could effectively modulate NMDA channel gating. In this case FBM still significantly accelerates the desensitization process at pH 7.4 and 6.4, but much less so at pH 8.4. The effect of FBM on desensitization thus is also pH-dependent. Fig. 1 D further shows that loss of use-dependence is most likely ascribable to the much stronger inhibitory effect of FBM on the peak currents at pH 8.4 than at pH 7.4 in the presence of 100 μM to 3 mM FBM. On the other hand, extracellular proton has only negligible effect on the IC50 value for FBM inhibition of the sustained (steady-state) NMDA currents (IC50 = 0.71 and 0.64 mM at pH 7.4 and 8.4, respectively, Fig. 1 E). We then explored the effect of FBM on the activation kinetics of the NMDA channel at different extracellular pH in more detail (Fig. 2). At pH 7.4 and 6.4, FBM evidently enhances rather than inhibits the NMDA currents elicited by very low concentrations (e.g., 6 μM) of NMDA and significantly accelerates the rising phase of NMDA currents, well consistent with the proposal that FBM is a gating modifier but not a pore blocker in these conditions (5). In sharp contrast, at pH 8.4 FBM neither enhances the small currents elicited by 6 μM NMDA (Fig. 2 C), nor accelerates the activation kinetics of the NMDA channel (Fig. 2 D). These findings, along with the much weakened use-dependence of FBM inhibition on NMDA currents (i.e., the much stronger inhibition of the peak NMDA current by FBM) at pH 8.4 (Fig. 1), strongly suggest that FBM has a significantly different mode of action on the NMDA channel with the ∼1 pH unit change. Unlike the cases at pH 7.4 and 6.4, FBM seems to have an additional mechanism of channel inhibition, such as pore block, at pH 8.4.

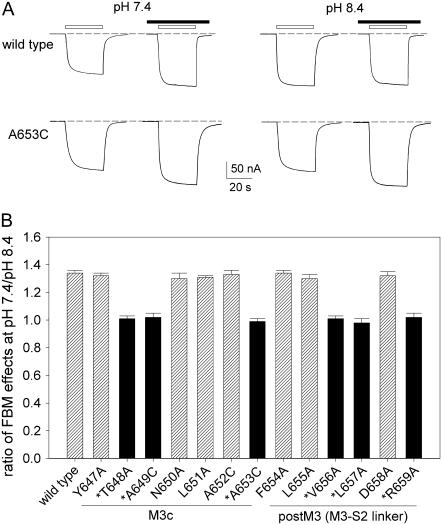

The differential effects of FBM between pH 7.4 and 8.4 are abolished in the mutant channels which are insensitive to extracellular proton

To confirm that the differential effects of FBM on NMDA currents between pH 7.4 and 8.4 are indeed dependent on extracellular pH, we investigated the FBM effects on the current elicited by 6 μM NMDA at pH 7.4 and 8.4 in the wild-type (NR1-2B) and NR1 mutant NMDA channels. Thirteen consecutive (Y647-R659) point mutations in the M3c and postM3 domains which both are reported to be critically related to proton sensitivity of the NMDA channel (23) were examined. Fig. 3 shows that FBM enhances the small current at pH 7.4 but not at pH 8.4 in the wild-type channel (132 ± 3% vs. 98 ± 2%, n = 6, p < 0.05), very similar to the findings from the dissociated neurons in Fig. 2. Although all 13 NR1 mutations generated functional channels, we found that 6 mutations no longer show significant differential effects of FBM on the NMDA current between pH 7.4 and 8.4. Most interestingly, these six residues (i.e., T648, A649, A653, V656, L657, and R659 in NR1) exactly coincide with the positions which are reported to be the probable proton sensor sites (23). These results further support that the subtle but significant difference of FBM effects between pH 7.4 and 8.4 is indeed modulated by extracellular proton. Because the protonation status of the side chains of the foregoing six residues are unlikely to be changed between pH 7.4 and 8.4, and most importantly because the six residues exactly coincide the previously reported proton-modulation sites of NMDA channel gating even in the absence of FBM, the interaction between external proton and FBM is most likely achieved indirectly or allosterically via their individual effects on NMDA channel conformations and functions.

FIGURE 3.

The differential effects of FBM on the current elicited by low concentrations of NMDA between pH 7.4 and 8.4 could be abolished by point mutations in M3c. (A) NMDA currents obtained from oocytes coexpressing either the wild-type or mutant NR1 and wild-type NR2B subunits were elicited by application of 6 μM NMDA plus 10 μM glycine in the absence and presence of 300 μM FBM. The bars above the current traces indicate application of the agonists (NMDA and glycine; open bar) and FBM (solid bar). It is evident that FBM enhances the small current at pH 7.4 but not at pH 8.4 in the wild-type channel (131% vs. 98%). In contrast, FBM enhances the current both at pH 7.4 and 8.4 in the A653C mutant channel (128% vs. 129%). The dashed lines indicate zero current level. Because of the limitation of perfusion speed in the oocyte preparation (oocytes are much larger than native neurons), NMDA currents observed in oocytes are mostly steady-state currents (including both open and desensitized NMDA channels), roughly equivalent to the late sustained (not early peak) currents observed in native neurons (Fig. 1 A). (B) Cumulative results are obtained with the same experimental protocol described in panel A (n = 4–6 for each different channel). The relative current is defined by the ratio between the amplitude of the steady-state currents elicited by 6 μM NMDA pulse in the presence and absence of 300 μM FBM in the same oocyte. The ratio of FBM effects on NMDA currents at pH 7.4/pH 8.4 is then given by the ratio between the relative current at pH 7.4 and 8.4. Positions marked with an asterisk (*) are the previously reported probable proton-modulation sites (23).

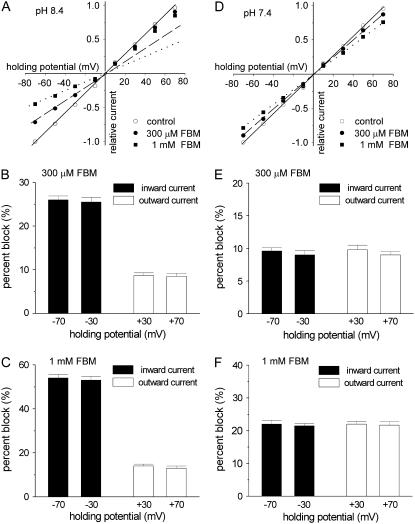

The inhibitory effect of FBM on NMDA currents is flow-dependent at pH 8.4 but not at pH 7.4

We further examined the possibility if FBM indeed becomes an effective NMDA channel pore blocker at pH 8.4. Fig. 4, A–C, shows that at pH 8.4 FBM significantly inhibits the peak NMDA currents at all negative holding potentials from −70 to −10 mV (i.e., when there are inward currents or the preponderant direction of current flow is inward). By contrast, the inhibitory effect of FBM is evidently smaller at all positive holding potentials from +10 to +70 mV (i.e., outward currents). However, comparison between the inhibitory effects at −70 and at −30 mV (or at +70 and at +30 mV) does not show voltage-dependence. The inhibitory effects remain similar if the direction of current flow remains the same (Fig. 4, B and C). These findings show that at pH 8.4 the inhibitory effect of FBM on NMDA currents is flow (direction)-dependent but not voltage-dependent, and is significantly stronger in inward than in outward currents. The flow-dependent blocking phenomenon could be observed in the other instances, and is always a strong evidence arguing that the inhibitor binds to the channel pore. For example, in the inward rectifier potassium channel the outward current is significantly inhibited by intrinsic intracellular pore blockers Mg2+ and polyamines, but the inward current is not (24–27). Although many NMDA channel pore blockers (e.g., Mg2+ and MK-801) do show voltage dependence of inhibition, these compounds are charged at physiological pH. FBM is a dicarbamate and is not significantly charged (protonated) at physiological or more alkaline pH (e.g., pH 8.4). The lack of voltage dependence of FBM inhibition on NMDA currents therefore is actually an expected rather than unexpected finding even for a FBM binding site in the pore, further substantiating that the differential inhibitory effects between +30 ∼ +70 mV and −30 ∼ −70 mV at pH 8.4 should be ascribed to the difference in (the direction of) current flow rather than membrane voltage. In sharp contrast to the findings at pH 8.4, the inhibitory effect of FBM does not show any flow dependence at pH 7.4 (Fig. 4, D–F), well consistent with the foregoing proposal that FBM is chiefly a gating modifier rather than a pore blocker at the physiological pH (5). We therefore conclude that FBM is an opportunistic pore blocker of the NMDA channel, with its pore-blocking effect effectively modulated by external proton (see Discussion for more details).

FIGURE 4.

The inhibitory effect of FBM on NMDA currents is flow-dependent at pH 8.4 but not at pH 7.4. (A) Current-voltage (I–V) plots of the NMDA channel from a representative cell. The currents activated by the application of 1mM NMDA and 0.3 μM glycine in the absence (control) and presence of 300 μM or 1 mM FBM at extracellular pH 8.4. Both the external and internal solutions contained 150 mM Na+. The peak NMDA currents are measured at holding potentials from −70 to +70 mV and normalized to the amplitude of control peak current measured at −70 mV in the same cell. I–V relationships of four negative holding potentials (−70, −50, −30, and −10 mV) are fitted with linear regression functions crossing the zero point. The solid, dashed, and dotted lines are for the control, 300 μM, and 1 mM FBM conditions, respectively. It is evident that the NMDA current in 300 μM and 1 mM FBM are off the fitting lines at all positive holding potentials (+10 to +70 mV), illustrating the differential inhibitory effect of FBM between inward and outward currents. (B,C) Cumulative results are obtained from seven cells with the same experimental protocol described in panel A. The percent block (inhibition) of FBM on the peak NMDA current at four holding potentials is summarized. The inhibitory effect of FBM is essentially the same at −30 and −70 mV (both inward currents, p > 0.05, n = 7) and also the same at +30 and +70 mV (both outward currents, p > 0.05, n = 7), but evidently different between −30 (or −70) mV and +30 (or +70) mV (p < 0.001, n = 7). (D) I–V plots of the NMDA channel from a representative cell were documented with the same experimental protocol as that in panel A, but here the extracellular pH was 7.4. In sharp contrast to the findings at pH 8.4, at pH 7.4 all data points at positive holding potentials stay on the fitting lines defined by the data points obtained at negative potentials. (E,F) Cumulative results are obtained from five cells with the same experimental protocol described in panel D. The percent block of FBM on the current at four holding potentials is shown. No significant differences are noted among these four holding potentials (p > 0.05, n = 5).

The inhibitory effect of FBM on NMDA currents is antagonized by external but not internal Na+ at pH 8.4

If FBM blocks the NMDA channel pore at pH 8.4, then the other travelers (e.g., Na+ ions) of the pore may interfere with the action of FBM. Fig. 5, A and B, shows that the inhibitory effect of FBM is significantly reduced when external Na+ is increased from 25 to 750 mM. However, the inhibition remains unchanged when the internal Na+ concentration is increased from 75 to 450 mM (Fig. 5 C). These findings suggest that FBM blocks the NMDA channel pore from the outside, and that the FBM binding site probably is located quite externally in the pore (see Discussion). The effect of external Na+ on FBM inhibition can be quantitatively described by the following equation,

|

(1) |

where Iexp, Imin, Imax, [Na+], and Kd denote the experimental current, the minimum current, the maximum current, the external Na+ concentration, and the dissociation constant of Na+ binding to the site affecting FBM inhibition, respectively. The best fits with Eq. 1 to the data points in Fig. 5 B give very similar apparent Kd values of 258 and 275 mM for the peak and sustained currents, respectively.

FBM has no effect on NMDA currents if applied internally

So far we have applied FBM to the cell from the external side. However, the uncharged form of FBM might cross the cell membrane easily. Because there is no continuous and rapid wash of the intracellular space, the FBM concentration in the very small intracellular space may build up or even become as high as that in the external solution. Therefore, one cannot tell whether the externally applied FBM inhibits the NMDA channel from the outside or from the inside based on the previous experiments. Taking advantage of the rapid and continuous solution change of the extracellular space in the experimental system, we examined the effect of internal FBM by adding 1 mM FBM to the pipette solution (Fig. 6). Under such circumstances the FBM crossing the membrane and reaching the outside would be quickly washed away, and thus the internally applied FBM should not build up any significant concentration in the external solution. The NMDA currents do not significantly decrease throughout the experiments (up to ∼25 min), and the current amplitude is always comparable to those observed with FBM-free internal solution (Fig. 6 A). Moreover, the inhibition induced by 300 μM external FBM is very similar no matter whether the internal solution contains 1 mM FBM or not, confirming that the NMDA current observed in the presence of 1 mM internal FBM is not a residual current already under significant inhibition (Fig. 6, B and C). These results, along with the finding that the inhibitory effect of FBM on NMDA currents is antagonized by external but not internal Na+ (Fig. 5), strongly indicate that FBM binds to the NMDA channel pore from the outside rather than from the inside.

FBM binds to the NMDA channel via a one-to-one binding stoichiometry

Given the very similar apparent affinities of FBM to the NMDA channel at pH 7.4 and 8.4 (IC50 = 0.71 and 0.64 mM, respectively; Fig. 1 E), the difference in binding energy between FBM binding to the channel at pH 7.4 and 8.4 is only ∼0.1 RT (product of gas constant and absolute temperature). This result may imply that there is only a relatively small conformational change in the FBM binding site itself when the extracellular pH is changed from 7.4 to 8.4. To elucidate the molecular basis underlying this apparently small conformational change, we further examined the kinetics of FBM binding to and unbinding from the activated NMDA channel in detail at extracellular pH 8.4. Fig. 7 A demonstrates the kinetics of development of and recovery from inhibition by 100 or 1000 μM FBM. It is evident that the kinetics of development of inhibition are FBM concentration-dependent, whereas the kinetics of recovery from inhibition are not. Fig. 7 B shows a linear correlation between the binding rates (inverses of the binding time constants) and FBM concentrations, indicating that FBM interacts with the NMDA channel via a one-to-one binding process (i.e., a simple bimolecular reaction) and a macroscopic binding rate constant of 4.4 × 104 M−1 s−1. The y-intercept of the linear regression fit to the macroscopic binding rate data in Fig. 7 B is ∼3.9 s−1, which is very much consistent with the inverses of current relaxation (unbinding rate) time constants (∼3.7 s−1), a value evidently independent of FBM concentrations. From the binding and unbinding rate constants, an apparent dissociation constant of ∼90 μM could be calculated for FBM binding to the steady-state activated NMDA channels (including both open and desensitized channels, as it is difficult to completely separate these two states with our experimental approaches here). A dissociation constant of ∼90 μM is well within the range of previously reported dissociation constants of FBM to the open and desensitized NMDA channels (∼110 and ∼55 μM, respectively) at pH 7.4 (5). Also, the kinetics of FBM binding to and unbinding from the activated channels at pH 8.4 are essentially the same as our previous reports (4.6 × 104 M−1 s−1 and 3.1–3.5 s−1, respectively) obtained at pH 7.4 (11). These findings, together with the very close IC50 values of FBM, are consistent with the idea that the FBM binding site of the NMDA channel undergoes only a small conformational change when the extracellular pH is changed from 7.4 to 8.4.

External Na+ modulates the rate of FBM binding to but not the rate of FBM unbinding from the NMDA channel at pH 8.4

Fig. 7, C and D, further shows that the binding rates of 300 μM FBM to the activated NMDA channel are reduced when external Na+ is increased from 50 to 450 mM (p < 0.05, n = 8, Fig. 7 C). Most interestingly, the unbinding rates are relatively unaltered with increasing concentrations of external Na+ (p > 0.05, n = 8, Fig. 7 D). These intriguing findings are consistent with the foregoing view that the inhibition of NMDA currents by FBM is reduced in high external Na+ in Fig. 5 B. It also implies that external Na+ and FBM may compete for a binding site located at the external pore mouth. Moreover, the fact that only the binding but not the unbinding rates of FBM are affected by external Na+ would suggest that this Na+ binding site is practically the most external (outmost) ionic site in the NMDA channel pore (see Discussion). The apparent affinity (dissociation constant) of Na+ to this outmost ionic site is ∼260 mM (Fig. 5 B), indicating that the occupancy of this site is not negligible in physiological concentrations (∼150 mM) of extracellular Na+.

The affinity of Na+ to the outmost ionic site in the NMDA channel pore is not significantly altered by a change of extracellular pH from 8.4 to 7.4

We have shown that Na+ and FBM compete for a common superficial binding site at the external pore mouth of the NMDA channel at pH 8.4. Because there is probably only a small conformational change in the FBM binding site between pH 8.4 and 7.4, it is interesting to see whether the affinity of Na+ to the outmost ionic site is altered by a change of extracellular pH from 8.4 to 7.4. Fig. 8 A shows that FBM has little inhibition on the peak currents but much more prominent inhibitory effect on the sustained currents at pH 7.4 (i.e., use-dependent inhibition), and the inhibition is decreased when the external Na+ concentration is increased from 25 to 750 mM. Again, the inhibitory effect of FBM remains unchanged if internal Na+ is increased from 75 to 450 mM at pH 7.4 (Fig. 8 B). These findings suggest that the gating-modification effect of FBM on NMDA channels at pH 7.4 is also antagonized by external but not internal Na+, consistent with the idea that the FBM binding site is located at the external pore mouth, directly facing the external rather than the internal solution. Because we have kept the osmolarity roughly equal on both sides of the membrane with the addition of sucrose (see Materials and Methods), the lack of effect of increased internal Na+ on FBM inhibition at both pH 8.4 and 7.4 (Figs. 5 C and 8 B) would argue against the antagonizing effect of increased external Na+ on FBM inhibition being ascribable to some nonspecific effects (e.g., different osmolarities) of the solutions. Quantitatively, the apparent Kd of Na+ binding to the outmost ionic site at pH 7.4 could also be calculated using Eq. 1, giving a value of 262 mM (Fig. 8 A). This Kd value of 262 mM at pH 7.4 is very similar to those obtained at pH 8.4 (258 and 275 mM, Fig. 5 B), indicating that FBM binds to the same site in the NMDA channel at pH 7.4 (acting as a gating modifier but not a pore blocker) and at pH 8.4 (showing an evident pore-blocking effect). The binding site, however, would undergo delicate but functionally important conformational changes upon the one pH unit change from 7.4 to 8.4. In this regard, it is interesting to note that extracellular Na+ ions significantly antagonize the inhibitory effect of FBM on NMDA currents at both pH 8.4 and 7.4 (Figs. 5 and 8). By contrast, the Na+ ions flowing through the pore significantly attenuate the inhibitory effect of FBM only at pH 8.4 but not at pH 7.4 (Fig. 4). The FBM binding site thus should be located in the ion conduction pathway, and at a position very close to the extracellular rather than the intracellular milieu (see Discussion).

DISCUSSION

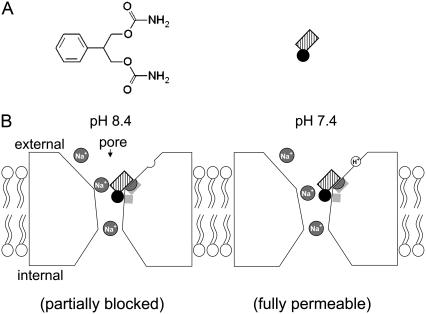

FBM acts as an opportunistic NMDA channel pore blocker modulated by extracellular proton

Our previous study (5) has demonstrated that FBM is a use-dependent gating modifier of the NMDA channel at physiological pH (i.e., pH 7.4). At its therapeutic concentrations (50–300 μM), FBM effectively enhances NMDA channel activation and especially the desensitization processes. In this study, we demonstrated that although FBM is an effective gating modifier rather than a pore blocker at pH 7.4, it is turned into an evident pore blocker at pH 8.4. The similar inhibition of the peak current and the late sustained (steady-state) current at pH 8.4 (Fig. 1) further implies that FBM could bind to the closed state of the NMDA channel and then decrease ionic flow upon channel opening. These findings suggest that FBM is a pore blocker, but not an open channel blocker, which can only bind to and block the pore after channel opening. Although native neurons express several subtypes of NMDA channels with different desensitization kinetics properties (28) and different sensitivity to FBM (4,16). The NMDA channels in neonatal rat hippocampal neurons (that we used in this study) are mainly composed of NR1-2B subunits (29). Also, the very similar findings that the differential effects of FBM on NMDA currents between pH 7.4 and 8.4 are observed in both native (Fig. 2) and recombinant NR1-2B (Fig. 3 A) NMDA channels also indicate a genuine interaction between proton and FBM on the NMDA channel protein. Moreover, the apparent affinity (IC50) of FBM in this study (0.71 and 0.64 mM at pH 7.4 and 8.4, respectively; Fig. 1 E) is very similar to that observed in recombinant NR1-2B NMDA channels (e.g., 0.93 and 0.95 mM at pH 7.4 and 8.3, respectively in (4); 0.52 mM at pH 7.4 in (16)). The significant different effects of FBM between pH 7.4 and 8.4 (Figs. 1–4) thus may be viewed as findings mainly from the NR1-2B NMDA channels, and cannot be ascribed to a heterogeneous population of the NMDA channel in native neurons.

The FBM binding site is located at the external pore mouth and shows a delicate proton-modulated local conformational change

We show that the rate of FBM binding to the activated NMDA channel is linearly correlated with the FBM concentration at pH 8.4 (Fig. 7 B). FBM thus very likely binds to the NMDA channel via a one-to-one binding stoichiometry (i.e., a simple bimolecular reaction) with a binding rate constant of 4.4 × 104 M−1 s−1 at pH 8.4. These findings are qualitatively and quantitatively very similar to those obtained at pH 7.4 (11). The striking similarity implies that FBM binds to the same site in the NMDA channel at pH 7.4 and 8.4. Also, this binding site itself probably undergoes only a small conformational change to make FBM a partial pore blocker when the extracellular pH is increased from 7.4 to 8.4 (and probably also in some other experimental conditions, e.g., (6,7)). This intriguing opportunistic pore blocking effect would locate the FBM binding site to a pore region of critical dimensions, most likely the junction of a widened and a narrow part of the ion conduction pathway (so that its pore-blocking effect could be dramatically altered by a small local conformational change). Also, only externally but not internally applied FBM could significantly inhibits NMDA currents (Fig. 6), and only external but not internal Na+ ions show an antagonistic effect on FBM binding (Figs. 5 and 8). The FBM binding site thus is very likely located at the external pore mouth of the NMDA channel pore (probably the inner end of the external vestibule and coincide with the outmost ionic site; see below and Fig. 9).

FIGURE 9.

A schematic model describes the extracellular proton-modulated pore-blocking effect of FBM on the NMDA channel. (A) The chemical formula of FBM is shown in the left panel. The phenyl group of FBM is shown by a black circle, and the symmetrical propanediol dicarbamate group is shown by a hatched rectangle in the right panel. (B) A presumable proton sensor (open semicircle) is depicted at the external vestibule of the NMDA channel protein. The two light shaded areas in the channel protein mark the location of the binding ligands for FBM. At extracellular pH 8.4, FBM binds to the light shaded areas in the external pore mouth to compromise the ion conduction pathway and partially block ionic flow (left panel). When the proton sensor is more occupied at pH 7.4, the external pore mouth undergoes a delicate local conformational change and the ion conduction pathway of the FBM-bound channel may therefore remain patent to the permeating Na+ ions (right panel). The molecular interaction between FBM and its binding ligands, however, is similar at pH 7.4 and 8.4. The FBM binding site presumably is conceivably located at a pore region of critical dimensions, most likely the junction of a widened and a narrow part (presumably the junction of the external vestibule and the single-file region of the pore), so that FBM could behave as an opportunistic pore blocker modulated by the delicate local conformational change caused by extracellular proton binding. On the other hand, the outmost ionic (Na+) site (shaded semicircle) of the NMDA channel pore and the FBM binding site probably overlap each other. Because this ionic site essentially faces the external solution, FBM binding would be affected by only external but not internal Na+.

FBM may only partially block the NMDA channel at extracellular pH 8.4

It is very intriguing that we have an IC50 value of ∼0.6 mM (Fig. 1 E), but a much smaller value (∼90 μM) for the dissociation constant of FBM to the activated (open and desensitized) NMDA channels in Fig. 7 B. This finding would suggest that although FBM may affect current flow through the NMDA channel pore at pH 8.4, the inhibitory effect of FBM on NMDA currents remains partly or even largely ascribable to gating modification. In other words, FBM does not seem to block the NMDA channel pore completely at pH 8.4. A rough estimate of the extent of pore blocker at pH 8.4 may be derived from the findings in Fig. 1. The relative currents at pH 8.4 in Fig. 1 B are ∼10% (sustained currents) to ∼20% (peak currents) smaller than those at pH 7.4 and 6.4. Assuming that 300 μM FBM could occupy most of the activated NMDA channels (the apparent dissociation constants of FBM binding to the open and desensitized NMDA channels are ∼110 and ∼55 μM, respectively; (5)), the 10–20% further decrease in relative currents would suggest a decrease in NMDA channel conductance by only 10–20% in case of roughly similar gating modification between pH 7.4 and 8.4. This very modest pore-blocking effect, and the usual existence of subconductance levels in NMDA channels, may preclude an effective and straightforward demonstration of the pore-blocking effect of FBM at pH 8.4 based on the single-channel recordings. The very modest (10–20%) decrease in NMDA channel conductance may also explain the nearly identical concentration-response curves of FBM at pH 7.4 and 8.4 in Fig. 1 E, and the relatively abrupt change of the relative currents or activation speeds from 1.3 to 1.5 (pH 7.4) to 1.00–1.05 at pH 8.4 in Fig. 2, C and D. The development of the small pore-blocking effect of FBM at pH 8.4 is also consistent with the idea that the FBM binding site may only undergo a small (but functionally significant) local conformational change upon the one pH unit change from 7.4 to 8.4 (see also Fig. 9).

The FBM binding site overlaps the outmost ionic site in the NMDA channel pore

We have argued that the FBM binding site is very likely located at the junction of a widened and a narrow part at the external pore mouth of the NMDA channel, and overlaps with a Na+ binding site. Most interestingly, the antagonistic effect of external Na+ on FBM binding is characterized by decreased binding rates but essentially unchanged unbinding rates of FBM with increasing concentrations of external Na+ (Fig. 7, C and D). This finding indicates that this overlapping Na+ site is practically the most external (outmost) ionic site in the NMDA channel pore. In other words, if there was another ionic binding site which could be significantly occupied with ∼150 mM Na+ and was located external to the FBM binding site in the pore, the unbinding rate of FBM would have been significantly decreased with increasing concentrations of external Na+ in Fig. 7 D. Functionally speaking, this outmost ionic site most likely is located in the widened vestibule external to the narrow constriction or presumably the selectivity filter of the pore, and thus is effectively occupied by only external rather than internal Na+ (which readily dissipates into the external milieu when permeating to this point). The apparent affinity of Na+ to this outmost ionic site is not high (Kd = ∼260 mM, Figs. 5 B and 8 A). However, it remains a possibility that Na+ binding to this site may play a role in the molecular operation of the NMDA channel in physiological conditions, which usually dictate ∼150 mM Na+ in the extracellular fluid in mammals.

Extracellular proton, Na+, FBM, and NMDA channel gating may have an orchestrating effect on the external pore mouth

Extracellular proton is an effective modulator of the NMDA channel, and there could be a tonic inhibition of NMDA currents by ∼50% at physiological pH (17–20). Banke et al. further reported that submicromolar extracellular proton effectively inhibited NMDA currents by trapping the channel in a nonconducting state, and thus there is a tight coupling between the proton sensor and channel gating (30). Using site-directed mutagenesis and homology modeling, Low et al. reported that the residues clustered in both the extracellular (or C-terminal) end of the second transmembrane (M3c) domain and the adjacent linker to the ligand-binding domain S2 (M3-S2 linker) of the NR1 and NR2 subunits significantly modulated the proton sensitivity of the NMDA channel (23). Interestingly, we also demonstrate that the differential effects of FBM on NMDA currents between pH 7.4 and 8.4 are abolished by point mutations (in M3c and M3-S2 linker of NR1), which exactly coincide with the probable proton sensor sites reported by Low et al. (23). On the other hand, the M3c domain probably also forms the main part of the external vestibule of the NMDA channel pore (31,32), and could be critically related to channel gating (23,33–35). Extracellular proton binding thus may delicately but significantly alter the local conformation of (the inner end of) the external vestibule, which harbors important drug (e.g., FBM) binding sites and the outmost ionic (e.g., Na+) site of the NMDA channel pore (Fig. 9). The picture that the outmost ionic site overlaps with the FBM binding site would also be consistent with the previous view that there may be a strong coupling between permeation and gating in the NMDA channel (36,37). The external pore mouth thus very likely plays an essential role in the molecular physiology (e.g., channel gating, ion permeation, and proton modulation) and pharmacology (e.g., gating modifiers such as FBM) of the NMDA channel. In this regard, FBM may not only be a clinically important anticonvulsant, but also serve as a powerful probe to study the molecular operation and structural correlates of the NMDA channel.

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. S. Nakanishi and K. Williams for sharing cDNAs encoding NR1a and NR2B subunits.

This work was supported by grant No. NSC95-2320-B-002-025 from the National Science Council and grant No. NHRI-EX96-9606NI from the National Health Research Institutes, Taiwan. Huai-Ren Chang is a recipient of the MD-PhD Predoctoral Fellowship No. DD9402C91 from the National Health Research Institutes, Taiwan.

Editor: David S. Weiss.

References

- 1.Rogawski, M. A. 1992. The NMDA receptor, NMDA antagonists and epilepsy therapy. A status report. Drugs. 44:279–292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rogawski, M. A. 1998. Mechanism-specific pathways for new antiepileptic drug discovery. Adv. Neurol. 76:11–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chen, H. S., and S. A. Lipton. 2006. The chemical biology of clinically tolerated NMDA receptor antagonists. J. Neurochem. 97:1611–1626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kleckner, N. W., J. C. Glazewski, C. C. Chen, and T. D. Moscrip. 1999. Subtype-selective antagonism of N-methyl-d-aspartate receptors by felbamate: insights into the mechanism of action. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 289:886–894. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kuo, C.-C., B.-J. Lin, H.-R. Chang, and C.-P. Hsieh. 2004. Use-dependent inhibition of the N-methyl-d-aspartate currents by felbamate: a gating modifier with selective binding to the desensitized channels. Mol. Pharmacol. 65:370–380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rho, J. M., S. D. Donevan, and M. A. Rogawski. 1994. Mechanism of action of the anticonvulsant felbamate: opposing effects on N-methyl-d-aspartate and gamma-aminobutyric acid-A receptors. Ann. Neurol. 35:229–234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Subramaniam, S., J. M. Rho, L. Penix, S. D. Donevan, R. P. Fielding, and M. A. Rogawski. 1995. Felbamate block of the N-methyl-d-aspartate receptor. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 273:878–886. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Borowicz, K. K., B. Piskorska, Z. Kimber-Trojnar, R. Malek, G. Sobieszek, and S. J. Czuczwar. 2004. Is there any future for felbamate treatment? Pol. J. Pharmacol. 56:289–294. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rogawski, M. A., and W. Loscher. 2004. The neurobiology of antiepileptic drugs. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 5:553–564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pellock, J. M., E. Faught, I. E. Leppik, S. Shinnar, and M. L. Zupanc. 2006. Felbamate: consensus of current clinical experience. Epilepsy Res. 71:89–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chang, H.-R., and C.-C. Kuo. 2007. Characterization of the gating conformational changes in the felbamate binding site in NMDA channels. Biophys. J. 93:456–466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gallagher, M. J., H. Huang, D. B. Pritchett, and D. R. Lynch. 1996. Interactions between ifenprodil and the NR2B subunit of the N-methyl-d-aspartate receptor. J. Biol. Chem. 271:9603–9611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kew, J. N., G. Trube, and J. A. Kemp. 1996. A novel mechanism of activity-dependent NMDA receptor antagonism describes the effect of ifenprodil in rat cultured cortical neurones. J. Physiol. 497:761–772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mott, D. D., J. J. Doherty, S. Zhang, M. S. Washburn, M. J. Fendley, P. Lyuboslavsky, S. F. Traynelis, and R. Dingledine. 1998. Phenylethanolamines inhibit NMDA receptors by enhancing proton inhibition. Nat. Neurosci. 1:659–667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Perin-Dureau, F., J. Rachline, J. Neyton, and P. Paoletti. 2002. Mapping the binding site of the neuroprotectant ifenprodil on NMDA receptors. J. Neurosci. 22:5955–5965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Harty, T. P., and M. A. Rogawski. 2000. Felbamate block of recombinant N-methyl-d-aspartate receptors: selectivity for the NR2B subunit. Epilepsy Res. 39:47–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tang, C. M., M. Dichter, and M. Morad. 1990. Modulation of the N-methyl-d-aspartate channel by extracellular H+. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 87:6445–6449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Traynelis, S. F., and S. G. Cull-Candy. 1990. Proton inhibition of N-methyl-d-aspartate receptors in cerebellar neurons. Nature. 345:347–350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Traynelis, S. F., and S. G. Cull-Candy. 1991. Pharmacological properties and H+ sensitivity of excitatory amino acid receptor channels in rat cerebellar granule neurones. J. Physiol. 433:727–763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Traynelis, S. F., M. Hartley, and S. F. Heinemann. 1995. Control of proton sensitivity of the NMDA receptor by RNA splicing and polyamines. Science. 268:873–876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pahk, A. J., and K. Williams. 1997. Influence of extracellular pH on inhibition by ifenprodil at N-methyl-d-aspartate receptors in Xenopus oocytes. Neurosci. Lett. 225:29–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Moriyoshi, K., M. Masu, T. Ishii, R. Shigemoto, N. Mizuno, and S. Nakanishi. 1991. Molecular cloning and characterization of the rat NMDA receptor. Nature. 354:31–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Low, C. M., P. Lyuboslavsky, A. French, P. Le, K. Wyatte, W. H. Thiel, E. M. Marchan, K. Igarashi, K. Kashiwagi, K. Gernert, K. Williams, S. F. Traynelis, and F. Zheng. 2003. Molecular determinants of proton-sensitive N-methyl-d-aspartate receptor gating. Mol. Pharmacol. 63:1212–1222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Loussouarn, G., L. J. Marton, and C. G. Nichols. 2005. Molecular basis of inward rectification: structural features of the blocker defined by extended polyamine analogs. Mol. Pharmacol. 68:298–304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kurata, H. T., L. J. Marton, and C. G. Nichols. 2006. The polyamine binding site in inward rectifier K+ channels. J. Gen. Physiol. 127:467–480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Makary, S. M., T. W. Claydon, K. M. Dibb, and M. R. Boyett. 2006. Base of pore loop is important for rectification, activation, permeation, and block of Kir3.1/Kir3.4. Biophys. J. 90:4018–4034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhang, Y. Y., H. Sackin, and L. G. Palmer. 2006. Localization of the pH gate in Kir1.1 channels. Biophys. J. 91:2901–2909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cull-Candy, S., S. Brickley, and M. Farrant. 2001. NMDA receptor subunits: diversity, development and disease. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 11:327–335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Monyer, H., N. Burnashev, D. J. Laurie, B. Sakmann, and P. H. Seeburg. 1994. Developmental and regional expression in the rat brain and functional properties of four NMDA receptors. Neuron. 12:529–540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Banke, T. G., S. M. Dravid, and S. F. Traynelis. 2005. Protons trap NR1/NR2B NMDA receptors in a nonconducting state. J. Neurosci. 25:42–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Beck, C., L. P. Wollmuth, P. H. Seeburg, B. Sakmann, and T. Kuner. 1999. NMDAR channel segments forming the extracellular vestibule inferred from the accessibility of substituted cysteines. Neuron. 22:559–570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kashiwagi, K., T. Masuko, C. D. Nguyen, T. Kuno, I. Tanaka, K. Igarashi, and K. Williams. 2002. Channel blockers acting at N-methyl-d-aspartate receptors: differential effects of mutations in the vestibule and ion channel pore. Mol. Pharmacol. 61:533–545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kohda, K., Y. Wang, and M. Yuzaki. 2000. Mutation of a glutamate receptor motif reveals its role in gating and δ2 receptor channel properties. Nat. Neurosci. 3:315–322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jones, K. S., H. M. VanDongen, and A. M. VanDongen. 2002. The NMDA receptor M3 segment is a conserved transduction element coupling ligand binding to channel opening. J. Neurosci. 22:2044–2053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yuan, H., K. Erreger, S. M. Dravid, and S. F. Traynelis. 2005. Conserved structural and functional control of N-methyl-d-aspartate receptor gating by transmembrane domain M3. J. Biol. Chem. 280:29708–29716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schneggenburger, R., and P. Ascher. 1997. Coupling of permeation and gating in an NMDA-channel pore mutant. Neuron. 18:167–177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chen, N., B. Li, T. H. Murphy, and L. A. Raymond. 2004. Site within N-methyl-d-aspartate receptor pore modulates channel gating. Mol. Pharmacol. 65:157–164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]