Abstract

A model of autocrine signaling in cultures of suspended cells is developed on the basis of the effective medium approximation. The fraction of autocrine ligands, the mean and distribution of distances traveled by paracrine ligands before binding, as well as the mean and distribution of the ligand lifetime are derived. Interferon signaling by dendritic immune cells is considered as an illustration.

INTRODUCTION

Autocrine loops can control the self-renewal and differentiation of stem cells (1), establish the spatial patterns of cell fates in development (2), enable local tissue repair (3), and protect cells from a variety of stresses (4). In addition to their ubiquitous role in tissues, autocrine loops can operate in experiments with cells in culture (5–9). These experiments can be done in one of the two formats. In the case of experiments with cultures of adherent cells, the cells are distributed in two dimensions and secreted ligands are diffusing in the overlaying culture medium (10,11). In the second format, cells are suspended in the three-dimensional medium (12–16).

Independently of the experimental format, one is frequently interested in the following properties of ligand trajectories (5,6,8,9,17). First, it is important to determine the probability that a ligand trajectory, initiated at the cell surface, is recaptured by the same (“parent”) cell. This probability is denoted by  Clearly,

Clearly,  is the fraction of the ligands that bind to the cell's neighbors. In this article, the ligands recaptured by the parent cell are called “autocrine”, whereas the ones captured by the cell's neighbors are called “paracrine”. Next, it is important to determine the distribution of lifetimes for autocrine and paracrine ligands. The corresponding probability densities are denoted by

is the fraction of the ligands that bind to the cell's neighbors. In this article, the ligands recaptured by the parent cell are called “autocrine”, whereas the ones captured by the cell's neighbors are called “paracrine”. Next, it is important to determine the distribution of lifetimes for autocrine and paracrine ligands. The corresponding probability densities are denoted by  and

and  Based on these probability densities one can define the average lifetimes of autocrine and paracrine ligands,

Based on these probability densities one can define the average lifetimes of autocrine and paracrine ligands,  which provide the natural timescales for the lifetimes of autocrine and paracrine signals. The length scale of paracrine signals can be obtained from the probability density of the ligand trapping points,

which provide the natural timescales for the lifetimes of autocrine and paracrine signals. The length scale of paracrine signals can be obtained from the probability density of the ligand trapping points,  and its first moment,

and its first moment,

Although it is difficult to measure these properties of ligand trajectories, they might be predicted on the basis of biophysical models or extracted from measurements of cellular responses (18,9). One of the goals of modeling is to connect these experimentally inaccessible properties of autocrine systems to the properties of individual cells, such as the levels of receptor expression, and parameters of the culture, such as cell densities and medium volumes (17).

Recently, we have developed models for autocrine signaling in experiments with epithelial layers and cultures of adherent cells (10,19–22). We have shown that this problem is effectively one-dimensional and can be efficiently handled using a boundary homogenization approach, whereby the heterogeneous surface of the tissue culture plate is approximated by a partially absorbing boundary condition, which depends on the properties of individual cells and the cell surface fraction (19,23,10). In this problem, the height of the liquid medium that covers the layer of adherent cells is an important parameter that controls the spatial and temporal characteristics of ligand trajectories (19,24). The geometry of the cell communication in cultures of suspended cells is completely different; hence, a new formalism is required for its analysis. The three-dimensional format is frequently encountered both in experiments with suspended cell cultures and in vivo (12–16,25).

Our analysis is motivated by the characterization of the autocrine and paracrine signals in cultures of dendritic cells (26). In response to viral infection, these cells start secreting IFNβ, which can affect both the parent cells and their uninfected neighbors. The secretion of the virus-induced IFNβ is essential for the maturation of dendritic cells. In this context, it is important to determine what fraction of secreted IFNβ is recaptured by the ligand-secreting cells, to estimate how long these ligands spend in the medium, and to establish their spatial range. In this article we show how to derive the analytical expressions for all of these important properties.

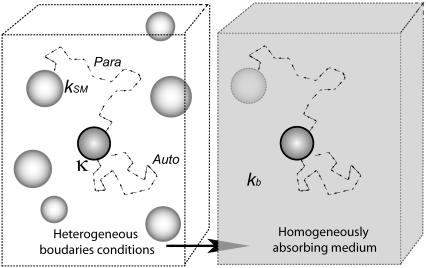

Our approach is based on the effective medium approximation. The three-dimensional heterogeneous medium with randomly distributed cells is replaced by a uniformly absorbing medium characterized by a volumetric trapping rate constant, which depends on the cell density, the ligand diffusivity, and the properties of individual cells (their size, the level of receptor expression, and the rate constant of ligand-receptor binding); see Fig. 1. The article is organized as follows. In the next section, we present the main results for the statistical properties of autocrine and paracrine trajectories. Next, we outline the main steps for their derivation. Then, we illustrate the application of these results to specific experiments with cultured dendritic cells. Finally, we conclude with the discussion of our results and outline the steps for their incorporation into more complex cellular and biochemical models of autocrine signaling.

FIGURE 1.

Effective medium approximation. The three-dimensional suspension of partially absorbing cells is approximated by an effective medium that is characterized by reaction rate constant kb. Two typical trajectories: autocrine and paracrine.

MODEL FORMULATION AND SUMMARY OF ANALYTICAL RESULTS

Consider spherical cells of radius R, which are uniformly distributed in the three-dimensional medium. The concentration of cells is denoted by c. Each cell has a fixed number of receptors, which is denoted by NR. Ligands, diffusing in the medium with diffusivity D, bind to receptors with the rate constant  Ligand binding to individual cells is characterized by an effective surface trapping rate κ (27,28):

Ligand binding to individual cells is characterized by an effective surface trapping rate κ (27,28):

|

(1) |

Using effective medium approximation, we introduce the volumetric rate constant, kb, which describes trapping of a ligand diffusing in the culture of suspended cells (29,4):

|

(2) |

where  is the Smoluchowski rate constant (30).

is the Smoluchowski rate constant (30).

Our results can be most conveniently expressed in terms of the dimensionless surface trapping rate,  :

:

|

(3) |

which is the ratio of the trapping probability to the escape probability for a ligand secreted by an isolated cell (4,28). This leads to the following expression for  :

:

|

(4) |

The dimensionless form of  given by the product of

given by the product of  and the characteristic diffusion time,

and the characteristic diffusion time,  can be written in terms of

can be written in terms of  and the cell volume fraction,

and the cell volume fraction,  :

:

|

(5) |

In the rest of this section we present our main results; their derivation is given in the next section.

The survival probability of the ligand released at  is given by

is given by

|

(6) |

where  is the complementary error function (31). The mean lifetime of the ligand,

is the complementary error function (31). The mean lifetime of the ligand,  is given by

is given by

|

(7) |

The second expression provides the relation between the average lifetime  and the characteristic diffusion time,

and the characteristic diffusion time,

The probability density for the distribution of the ligand trapping points,  has the following form:

has the following form:

|

(8) |

where r is the distance between the trapping point and the center of the parent cell,  is the Dirac delta function, and

is the Dirac delta function, and  is the Heaviside step function. The first term in the numerator is due to the autocrine ligands, which are recaptured by the same cell from which they were released. The second term in the numerator is due to the paracrine ligands. The fraction of autocrine ligands,

is the Heaviside step function. The first term in the numerator is due to the autocrine ligands, which are recaptured by the same cell from which they were released. The second term in the numerator is due to the paracrine ligands. The fraction of autocrine ligands,  is given by

is given by

|

(9) |

The third term in the denominator is due to the paracrine ligands, which bind to other cells in the medium. The fraction of such ligands,  is given by

is given by

|

(10) |

Both  and

and  can be expressed in terms of

can be expressed in terms of  and ω, which characterize individual cells and medium in which the ligands diffuse:

and ω, which characterize individual cells and medium in which the ligands diffuse:

|

The probability density,  which characterizes the distribution of the trapping points of paracrine ligands, has the following form:

which characterizes the distribution of the trapping points of paracrine ligands, has the following form:

|

(11) |

Based on this, the average distance traveled by paracrine ligands,  is given by

is given by

|

(12) |

This distance characterizes the length scale of cell communication by secreted ligands.

The probability densities for the lifetimes of autocrine and paracrine ligands,  and

and  are given by

are given by

|

(13) |

|

(14) |

where  From these distribution functions one can find the corresponding average lifetimes of autocrine and paracrine ligands,

From these distribution functions one can find the corresponding average lifetimes of autocrine and paracrine ligands,  and

and  :

:

|

(15) |

|

(16) |

As might be expected,  is always larger than

is always larger than  In the next two sections, we derive these results and demonstrate their application to the analysis of IFN β-mediated autocrine signaling in cultures of dendritic cells.

In the next two sections, we derive these results and demonstrate their application to the analysis of IFN β-mediated autocrine signaling in cultures of dendritic cells.

DERIVATIONS

Consider a ligand released from the surface of a cell located at the origin at  To describe the fate of this ligand one has to solve the diffusion equation with partially absorbing boundary conditions on surfaces of randomly located cells and then to average the result over cell configurations. Effective medium approximation allows us to convert this unsolvable problem into a solvable one. This approximation replaces the nonuniform medium by an effective uniform medium (see Fig. 1) in which ligand binding is described by the volumetric rate constant

To describe the fate of this ligand one has to solve the diffusion equation with partially absorbing boundary conditions on surfaces of randomly located cells and then to average the result over cell configurations. Effective medium approximation allows us to convert this unsolvable problem into a solvable one. This approximation replaces the nonuniform medium by an effective uniform medium (see Fig. 1) in which ligand binding is described by the volumetric rate constant  (Eq. 4).

(Eq. 4).

The probability density of finding the ligand at point r at time t is given by the propagator  which depends only on the distance

which depends only on the distance  because the problem is spherically symmetric. The propagator for this problem satisfies

because the problem is spherically symmetric. The propagator for this problem satisfies

|

(17) |

with the initial condition

|

(18) |

and the boundary condition on the surface of the “parent” cell located at the origin:

|

(19) |

Solving this problem, one can find the Laplace transform of  :

:

|

(20) |

where s is the parameter of the Laplace transform. In the rest of this section we use this result to derive the expressions in Eqs. 6–16.

Ligand lifetime

The survival probability of the ligand before its first binding,  is given by

is given by

|

(21) |

Its Laplace transform,  can be found using the Laplace transform of the propagator in Eq. 20

can be found using the Laplace transform of the propagator in Eq. 20

|

(22) |

Inversion of this transform leads to the result in Eq. 6. The average lifetime of the ligand before the first binding,  is defined by

is defined by

|

(23) |

where  is the probability density for the ligand lifetime. Using Eq. 22 we obtain the result in Eq. 7.

is the probability density for the ligand lifetime. Using Eq. 22 we obtain the result in Eq. 7.

Distribution of ligand trapping points

The ligand can be trapped either by the parent cell or by one of the cells in the bulk. The probability to be trapped by the parent cell between t and t + dt is  At the same time, the probability to be trapped at distance between r and r + dr, where

At the same time, the probability to be trapped at distance between r and r + dr, where  is

is  Integrating both of these probabilities with respect to time, we get the two marginal probabilities, which lead to the following expression for the probability density of the ligand trapping points:

Integrating both of these probabilities with respect to time, we get the two marginal probabilities, which lead to the following expression for the probability density of the ligand trapping points:

|

(24) |

Substituting the expression for the Laplace transform of the propagator, Eq. 20, we obtain the result in Eq. 8. One can check that  is normalized to unity:

is normalized to unity:

|

(25) |

The fractions of the autocrine and paracrine trajectories,  and

and  are given by

are given by

|

(26) |

|

(27) |

This leads to the expressions in Eqs. 9 and 10; clearly,

Using  we introduce the conditional probability density of the trapping points for paracrine trajectories,

we introduce the conditional probability density of the trapping points for paracrine trajectories,  :

:

|

(28) |

Combining this with the Laplace transform of the propagator, Eq. 20, we obtain the expression for  in Eq. 11. The first moment of this probability density gives the average trapping distance for the paracrine ligands,

in Eq. 11. The first moment of this probability density gives the average trapping distance for the paracrine ligands,  see Eq. 12.

see Eq. 12.

Distribution of the lifetimes for autocrine and paracrine trajectories

The probability densities of the lifetimes for autocrine and paracrine trajectories, denoted by  and

and  are introduced as follows. The fraction of trajectories recaptured by the parent cell is given by

are introduced as follows. The fraction of trajectories recaptured by the parent cell is given by  This probability has contributions from autocrine binding events at all times, from

This probability has contributions from autocrine binding events at all times, from  to

to  see Eq. 26. By definition,

see Eq. 26. By definition,  is the fraction of

is the fraction of  which is contributed by trajectories/ligands recaptured by between

which is contributed by trajectories/ligands recaptured by between  and

and  Since the probability to be recaptured by the parent cell between t and

Since the probability to be recaptured by the parent cell between t and  is

is  the probability density

the probability density  can be written as:

can be written as:

|

(29) |

Similarly, the probability density for the binding times in the bulk can be found as:

|

(30) |

The Laplace transform of  can be found using the Laplace transform of the propagator in Eq. 20 and the expression for

can be found using the Laplace transform of the propagator in Eq. 20 and the expression for  in Eq. 26:

in Eq. 26:

|

(31) |

Inversion of this transform leads to the expression in Eq. 13. The average lifetime of an autocrine ligand,  can be found as follows:

can be found as follows:

|

(32) |

The leads to the expression in Eq. 15. A similar sequence of steps leads to the Laplace transform of  :

:

|

(33) |

The inversion of this transform yields the result in Eq. 14. Using  we can find the average lifetime of the paracrine trajectories,

we can find the average lifetime of the paracrine trajectories,  which leads to the expression in Eq. 16.

which leads to the expression in Eq. 16.

Based on the definitions of

and

and  one can see that these probability densities satisfy

one can see that these probability densities satisfy

|

(34) |

As a consequence, the average lifetime of secreted ligand,  is the weighted sum of the average lifetimes of autocrine and paracrine ligands,

is the weighted sum of the average lifetimes of autocrine and paracrine ligands,  and

and  :

:

|

(35) |

APPLICATION TO IFNβ SIGNALING IN DENDRITIC CELLS

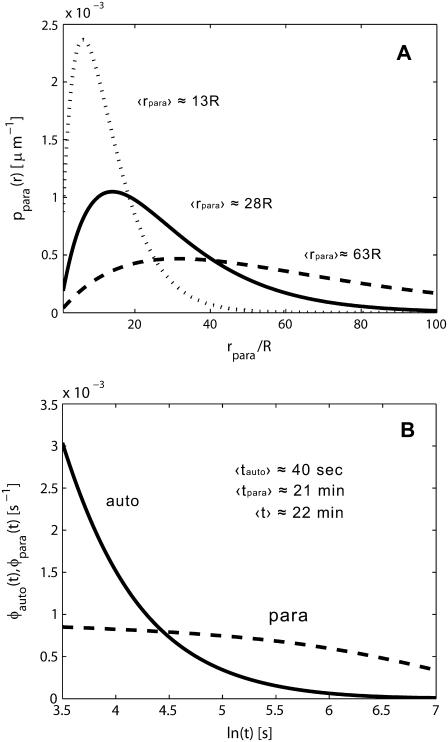

We have used our results to analyze the spatial and temporal ranges of secreted IFNβ molecules in experiments on early responses of cultured human dendritic cells to viral infection (26). In response to viral infection, dendritic cells begin to secrete IFNβ. Once captured by ligand-specific cell surface receptors, IFNβ can induce (after a delay) the secretion of IFNβ and IFNα. To know whether or not the secreted IFNβ will be recaptured by the secreting cell, and to determine the spatial and temporal ranges of IFNβ ligands, we collected values for the molecular, cellular, and physical parameters in this system (see Table 1). Using these parameters we have computed the distribution functions for the trapping distances and the lifetime or autocrine and paracrine ligands (Fig. 2). Furthermore, we found that the system operates in the regime of weak binding  and small volume fraction of the cells,

and small volume fraction of the cells,

TABLE 1.

Model parameters

| Parameter | Value |

|---|---|

| R | 25 μm |

| D | 102μm2s−1 |

| c | 10−6cells/μm3 |

| NR | 5×104/cell |

| kon | 107M−1s−1 |

| koff | 10−3s−1 |

|

5.1×10−3 |

|

2.6×10−2 |

FIGURE 2.

(A) Distribution of the ligand trapping points, computed for parameters corresponding to experiments with cultured dendritic cells. Solid line, standard parameters  (

( cell-to-cell distances); dashed line,

cell-to-cell distances); dashed line,  five times decreased (

five times decreased ( cell-to-cell distances); dotted line,

cell-to-cell distances); dotted line,  five times increased (

five times increased ( cell-to-cell distances). Note that the maximum of the probability density is shifted toward the parent cell origin as

cell-to-cell distances). Note that the maximum of the probability density is shifted toward the parent cell origin as  —or equivalently the cell concentration

—or equivalently the cell concentration  —increases. (B) Densities of the conditional probability densities for the lifetime of autocrine trajectories (solid line) and paracrine trajectories (dashed line). Parameters used to generate these plots are given in Table 1. Value of the mean characteristic lifetimes, computed as the means of the corresponding distribution functions; see text for details.

—increases. (B) Densities of the conditional probability densities for the lifetime of autocrine trajectories (solid line) and paracrine trajectories (dashed line). Parameters used to generate these plots are given in Table 1. Value of the mean characteristic lifetimes, computed as the means of the corresponding distribution functions; see text for details.

In this regime, the expressions above greatly simplify and reduce to:

|

(36) |

|

(37) |

|

(38) |

Using these simple formulas we predict that dendritic cells recapture 2.4% of secreted ligands, that their characteristic travel length is six cell-to-cell distances, and their characteristic lifetime in the medium is 20 min. Note that the characteristic time and length scales are independent of the cell size. Furthermore, since the system operates in the regime of slow binding, the characteristic timescale is independent of the ligand diffusivity. Clearly, the characteristic ligand trapping distance greatly exceeds both the cell size and the cell-cell distance. This can be considered as an a posteriori justification of our effective medium approach to the problem and shows that the analytical approach developed in this article is perfectly suited for analyzing autocrine signaling in experiments with cultured cells.

CONCLUDING REMARKS

Based on the effective medium approach, we developed a formalism for analyzing the spatial and temporal ranges of autocrine signaling in cultures of suspended cells. In contrast to the analysis of experiments with adherent cells, which relied on the boundary homogenization approach (19,23,10), our analysis in this article is based on the homogenization of the heterogeneous three-dimensional medium. The differences between autocrine signaling in the two experimental formats are clearly seen in the dependence of the statistical properties of ligand trajectories on the original parameters of the problems. For instance, one of the key parameters in experiments with adherent cells is the height of the liquid medium. Our previous work has shown that these experiments frequently operate in the regime where the height of the medium can be considered infinite (19,24,10). In this regime, both the average lifetimes of ligands and the average trapping distances are very large, and the kinetics of ligand removal from the medium is strongly nonexponential. This regime does not appear in the experiments with suspended cells. Indeed, in the first format, the ligand spends a lot of time in the medium free from traps and is trapped only at the boundary. In contrast, in the second format, the effective trapping rate in the medium is nonzero in all regions of space.

Our results provide the basis for the development of more complex models of autocrine signaling. Using the statistical properties of individual ligand trajectories derived in this article, it is possible to analyze the kinetics of ligand accumulation in the medium. This can be most conveniently done using the integral equations, which contain the ligand survival probabilities as their kernels (10). With the model for the extracellular ligand concentrations at hand, it should be possible to link the ligand and receptor part of the problem to the dynamics of intracellular signaling.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the National Institutes of Health contract HHSN266200500021C ADB No. N01-AI-50021 and the Intramural Research Program of the National Institutes of Health, Center for Information Technology.

Editor: Herbert Levine.

References

- 1.Kesari, S., and C. D. Stiles. 2006. The bad seed: PDGF receptors link adult neural progenitors to glioma stem cells. Neuron. 51:151–153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Freeman, M. 2000. Feedback control of intercellular signalling in development. Nature. 408:313–319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vermeer, P. D., L. A. Einwalter, T. O. Moninger, T. Rokhlina, J. A. Kern, J. Zabner, and M. J. Welsh. 2003. Segregation of receptor and ligand regulates activation of epithelial growth factor receptor. Nature. 422:322–326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shvartsman, S. Y., M. P. Hagan, A. Yacoub, P. Dent, H. S. Wiley, and D. A. Lauffenburger. 2002. Autocrine loops with positive feedback enable context-dependent cell signaling. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 282:C545–C559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.DeWitt, A., J. Dong, H. Wiley, and D. Lauffenburger. 2001. Quantitative analysis of the EGF receptor autocrine system reveals cryptic regulation of cell response by ligand capture. J Cell Sci 114:2301–2313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dong, J. Y., L. K. Opresko, P. J. Dempsey, D. A. Lauffenburger, R. J. Coffey, and H. S. Wiley. 1999. Metalloprotease-mediated ligand release regulates autocrine signaling through the epidermal growth factor receptor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 96:6235–6240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Janes, K. A., S. Gaudet, J. G. Albeck, U. B. Nielsen, D. A. Lauffenburger, and P. K. Sorger. 2006. The response of human epithelial cells to TNF involves an inducible autocrine cascade. Cell. 124:1225–1239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Maheshwari, G., H. S. Wiley, and D. A. Lauffenburger. 2001. Autocrine epidermal growth factor signaling stimulates directionally persistent mammary epithelial cell migration. J. Cell Biol. 155:1123–1128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wiley, H. S., S. Y. Shvartsman, and D. A. Lauffenburger. 2003. Computational modeling of the EGF-receptor system: a paradigm for systems biology. Trends Cell Biol. 13:43–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Monine, M. I., A. M. Berezhkovskii, E. J. Joslin, H. S. Wiley, D. A. Lauffenburger, and S. Y. Shvartsman. 2005. Ligand accumulation in autocrine cell cultures. Biophys. J. 88:2384–2390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Oehrtman, G. T., H. S. Wiley, and D. A. Lauffenburger. 1998. Escape of autocrine ligands into extracellular medium: experimental test of theoretical model predictions. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 57:571–582. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Griffith, L. G., and M. A. Swartz. 2006. Capturing complex 3D tissue physiology in vitro. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 7:211–224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nakashiro, K., S. Hara, Y. Shinohara, M. Oyasu, H. Kawamata, S. Shintani, H. Hamakawa, and R. Oyasu. 2004. Phenotypic switch from paracrine to autocrine role of hepatocyte growth factor in an androgen-independent human prostatic carcinoma cell line. Am. J. Pathol. 165:533–540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shaw, K. R., C. N. Wrobel, and J. S. Brugge. 2004. Use of three-dimensional basement membrane cultures to model oncogene-induced changes in mammary epithelial morphogenesis. J. Mammary Gland Biol. Neoplasia. 9:297–310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wrobel, C. N., J. Debnath, E. Lin, S. Beausoleil, M. F. Roussel, and J. S. Brugge. 2004. Autocrine CSF-1R activation promotes Src-dependent disruption of mammary epithelial architecture. J. Cell Biol. 165:263–273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhu, T., B. Starling-Emerald, X. Zhang, K. O. Lee, P. D. Gluckman, H. C. Mertani, and P. E. Lobie. 2005. Oncogenic transformation of human mammary epithelial cells by autocrine human growth hormone. Cancer Res. 65:317–324. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Loewer, A., and G. Lahav. 2006. Cellular conference call: external feedback affects cell-fate decisions. Cell. 124:1128–1130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lauffenburger, D. A., K. E. Forsten, B. Will, and H. S. Wiley. 1995. Molecular/cell engineering approach to autocrine ligand control of cell function. Ann. Biomed. Eng. 23:208–215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Batsilas, L., A. M. Berezhkovskii, and S. Y. Shvartsman. 2003. Stochastic model of autocrine and paracrine signals in cell culture assays. Biophys. J. 85:3659–3665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Muratov, C. B., and S. Y. Shvartsman. 2004. Signal propagation and failure in discrete autocrine relays. Phys. Rev. Lett. 93:118101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pribyl, M., C. B. Muratov, and S. Y. Shvartsman. 2003. Discrete models of autocrine signaling in epithelial layers. Biophys. J. 84:3624–3635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pribyl, M., C. B. Muratov, and S. Y. Shvartsman. 2003. Long-range signal transmission in autocrine relays. Biophys. J. 84:883–896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Berezhkovskii, A. M., Y. M. Makhnovskii, M. Monine, V. Y. Zitserman, and S. Y. Shvartsman. 2004. Boundary homogenization for trapping by patchy surfaces. J. Chem. Phys. 121:11390–11394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Berezhkovskii, A. M., L. Batsilas, and S. Y. Shvartsman. 2004. Ligand trapping in epithelial layers and cell cultures. Biophys. Chem. 107:221–227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Forsten, K. E., and D. A. Lauffenburger. 1994. The role of low-affinity interleukin-2 receptors in autocrine ligand-binding—alternative mechanisms for enhanced binding effect. Mol. Immunol. 31:739–751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fernandez-Sesma, A., S. Marukian, B. J. Ebersole, D. Kaminski, M. S. Park, T. Yuen, S. C. Sealfon, A. Garcia-Sastre, and T. M. Moran. 2006. Influenza virus evades innate and adaptive immunity via the NS1 protein. J. Virol. 80:6295–6304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lauffenburger, D. A., and J. J. Linderman. 1993. Receptors: Models for Binding, Trafficking, and Signaling. Oxford University Press, New York.

- 28.Shvartsman, S. Y., H. S. Wiley, W. M. Deen, and D. A. Lauffenburger. 2001. Spatial range of autocrine signaling: modeling and computational analysis. Biophys. J. 81:1854–1867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shoup, D., and A. Szabo. 1982. Role of diffusion in ligand-binding to macromolecules and cell-bound receptors. Biophys. J. 40:33–39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rice, S. A. 1985. Diffusion-Limited Reactions. Elsevier, Amsterdam, The Netherlands; New York.

- 31.Abramowitz, M., and I. A. Stegun. 1964. Handbook of Mathematical Tables with Formulas, Graphs, and Mathematical Tables. Dover Publications, Washington, DC.