Abstract

Bidirectional replication of Streptomyces linear plasmids and chromosomes from a central origin produces unpaired 3′-leading-strand overhangs at the telomeres of replication intermediates. Filling in of these overhangs leaves a terminal protein attached covalently to the 5′ DNA ends of mature replicons. We report here the essential role of a novel 80-kD DNA-binding protein (telomere-associated protein, Tap) in this process. Biochemical studies, yeast two-hybrid analysis, and immunoprecipitation/immunodepletion experiments indicate that Tap binds tightly to specific sequences in 3′ overhangs and also interacts with Tpg, bringing Tpg to telomere termini. Using DNA microarrays to analyze the chromosomes of tap mutant bacteria, we demonstrate that survivors of Tap ablation undergo telomere deletion, chromosome circularization, and amplification of subtelomeric DNA. Microarray-based chromosome mapping at single-ORF resolution revealed common endpoints for independent deletions, identified amplified chromosomal ORFs adjacent to these endpoints, and quantified the copy number of these ORFs. Sequence analysis confirmed chromosome circularization and revealed the insertion of adventitious DNA between joined chromosome ends. Our results show that Tap is required for linear DNA replication in Streptomyces and suggest that it functions to recruit and position Tpg at the telomeres of replication intermediates. They also identify hotspots for the telomeric deletions and subtelomeric DNA amplifications that accompany chromosome circularization.

Keywords: Telomere, terminal protein, telomere-associated protein: linear-DNA replication, chromosome circularization, DNA microarray, Tap

Streptomyces species have multiple biological properties that have made them important subjects for the study of mechanisms that regulate morphological and biochemical development in prokaryotes. Their complex life cycle, the high degree of cellular organization and morphological differentiation that exists within their colonies, and the genetic control mechanisms that regulate these events and processes have been of great biological interest (for review, see Champness and Chater 1994; Hopwood et al. 1995). Streptomyces synthesize a multitude of antimicrobial compounds and other agents used widely in medicine and agriculture (Chater 1992; Hopwood et al. 1995). Additionally, the presence in these organisms of plasmids and chromosomes that are linear, but which can circularize readily, has provided, and is continuing to provide, an attractive experimental system for fundamental investigations of telomere function and replicon evolution (Shiffman and Cohen 1992; Chang and Cohen 1994; Chang et al. 1996; Chen 1996; Lin and Chen 1997; Volff et al. 1997; Huang et al. 1998; Qin and Cohen 1998, 2000; Volff and Altenbuchner 1998, 2000; Wang et al. 1999; Bao and Cohen 2001; Yang and Losick 2001; Chen et al. 2002; Yang et al. 2002).

The replication of Streptomyces linear plasmids has been shown to proceed divergently from a site located near the center of the molecule and to generate 3′-leading-strand overhangs at the telomeres (Chang and Cohen 1994). The recessed 5′ ends of the lagging strands produced by the joining together of Okazaki fragments (Kurosawa et al. 1975) are then extended (i.e., “patched”) to produce full-length duplex DNA molecules (Chang and Cohen 1994). As Streptomyces linear chromosomes and linear plasmids have similar termini (Huang et al. 1998; Qin and Cohen 1998), and the linear chromosomes also replicate bidirectionally from an internal origin of replication (Musialowski et al. 1994), linear chromosome replication is presumed to also generate telomeric 3′ overhangs that require patching. Both linear plasmids and linear chromosomes of Streptomyces have a terminal protein attached covalently to their 5′ DNA ends (Hirochika and Sakaguchi 1982; Kinashi et al. 1987; Sakaguchi 1990; Lin et al. 1993; Bao and Cohen 2001; Yang et al. 2002). This protein is required for the propagation of these replicons in a linear form (Bao and Cohen 2001). Whereas purified terminal proteins of Bacillus subtilis phage φX29 and adenoviruses (Salas 1991; Yoo and Ito 1991; van der Vliet 1995; Hay 1996; Meijer et al. 2001) have been shown by biochemical studies to function in vitro to prime DNA synthesis, analogous data are not available for Streptomyces terminal proteins.

Sequence analysis indicates that the telomeres of Streptomyces linear replicons have similarities to, and differences with, the telomeres of eukaryotic chromosomes. The 3′ overhangs of both types of replicons contain multiple short repeats (Qin and Cohen 1998; Huang et al. 1998; for eukaryotes, see review, Greider 1996; Lingner and Cech 1998; McEachern et al. 2000; Blackburn 2001). However, whereas Streptomyces telomeres contain inverted repeats, eukaryote telomeres consist of a long series of tandem direct repeats. Moreover, the proteins that bind to telomeres of eukaryotes are not covalently attached to the terminus (Greider 1996; Bryan and Cech 1999; Blackburn 2001).

Earlier work has identified genes encoding the terminal proteins of Streptomyces spp. linear plasmids and chromosomes (i.e., terminal protein genes, tpg's; Bao and Cohen 2001; Yang et al. 2002). During our investigations of the chromosomally encoded terminal protein gene of Streptomyces lividans (i.e., tpgL; Bao and Cohen 2001), we observed, immediately 5′ to tpgL on the S. lividans chromosome, a gene (herein named telomere-associated protein gene, tap) whose position and sequence we found to be highly conserved among multiple streptomycetes. We report here that the Tap protein is essential for the replication of Streptomyces chromosomes and plasmids in a linear form, and that Tap recruits Tpg to telomere termini by interacting with both Tpg and specific sequences on the 3′ overhang of telomeric DNA. Using sequence analysis, hybridization of Streptomyces coelicolor chromosomal DNA arrayed on glass slides, and a series of computer programs that apply knowledge-based algorithms to microarray analysis (Genetic Analysis By Rules Incorporating Expert Logic, GABRIEL; Pan et al. 2002), we show that telomere deletion, chromosome circularization, and amplification of subtelomeric DNA occur in bacteria mutated in the tap gene, map the deletion and amplification boundaries at single-gene resolution, and determine gene copy number in amplified DNA segments.

Results

A conserved putative ORF is located 5′ to tpg genes in multiple Streptomyces spp.

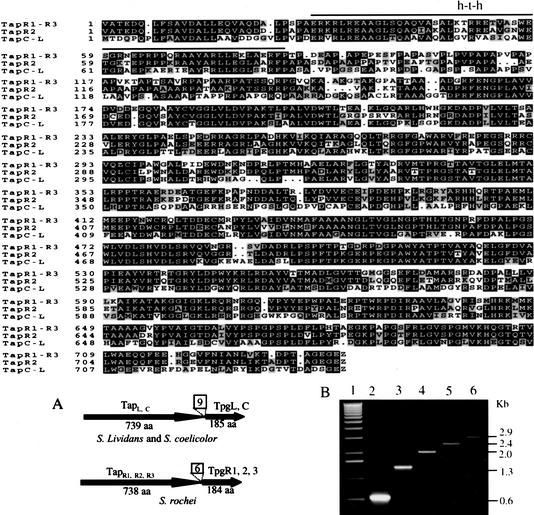

During experiments that identified and characterized terminal proteins (Tpg proteins; Bao and Cohen 2001) linked to 5′ DNA ends of Streptomyces spp. linear replicons, we carried out Frame program analysis (Bibb et al. 1984) of genomic DNA sequences near the chromosomal tpg loci of Streptomyces rochei (cosmids pBC65, pBC66 and pBC67 of our S. rochei library) and S. lividans (cosmid pBC30 of our S. lividans library). This analysis identified conserved putative ORFs (Fig. 1, top) that are located immediately 5′ to the tpg genes of both species and are separated from tpg genes by 6 or 9 bp (Fig. 1A). Examination of the genomic DNA sequence of S. coelicolor (SC8D11.24; Bentley et al. 2002; http://www.sanger.ac.uk/Projects/S_coelicolor) revealed a similar ORF at a corresponding location. As the three tpg-proximal ORFs include a predicted helix–turn–helix DNA-binding motif (HTH_XRE family domain, overlined in Fig. 1, top), as indicated by Simple Modular Architecture Research Tool (SMART) analysis, they were speculatively designated as encoding telomere-associated DNA-binding proteins. Subsequent studies (see below) have established the correctness of this notion, and we have retained the telomere-associated protein (Tap) designation. The Tap ORFs of S. lividans (TapL) and S. coelicolor (TapC) are identical, as are two analogous ORFs located 5′ to the tpgR1 and tpgR3 genes of S. rochei linear replicons. The S. rochei and S. lividans Tap proteins show 56% sequence identity and 67% similarity. BLAST program analysis of GenBank databases showed no other homologies with Tap.

Figure 1.

Tap ORFs in vicinity of terminal protein genes (tpg). (Top) Alignment of the amino acid sequences of Tap proteins in Streptomyces coelicolor (TapC), Streptomyces lividans (TapL), and Streptomyces rochei (TapR1, TapR2, and TapR3). TapR1-R3, TapR1 or TapR3; TapC-L, TapC or TapL. (A) Schematic map of gene arrangements of tpg and tap in S. rochei (TapR1,R2,R3 and TpgR1, 2, 3), S. lividans (TapL and TpgL), and S. coelicolor (TapC and TpgC). The number of nucleotides between the stop codon of the tap gene and the start codon of the tpg gene are shown in the boxes. (B) Reverse transcriptase (RT)–PCR analysis of tap and tpg in S. lividans 1326. (Lane 1) 1-kb DNA ladder. (Lane 2) RT–PCR product of the primer pair of RT–cDNA and RT_0.6kb. (Lane 3) RT–PCR product of the primer pair of RT–cDNA and RT_1.3kb. (Lane 4) RT–PCR product of the primer pair of RT–cDNA and RT_2.0kb. (Lane 5) RT–PCR product of the primer pair of RT–cDNA and RT_2.4kb. (Lane 6) RT–PCR product of the primer pair of RT–cDNA and RT_2.9kb.

The positional relationship between tap and tpg genes, as conserved in several Streptomyces species, suggests that the tap and tpg genes may constitute a polycistronic operon. Amplification of S. lividans total RNA by RT–PCR using a 3′ primer complementary to tpg (i.e., primer RT–cDNA) and five 5′ primers complementary to different sequences within the tap gene yielded products having sizes consistent with this interpretation (Fig. 1B). The longest RT–PCR product, which was amplified by the most 5′ of the tap-specific primers (i.e., primer RT-2.9 kb) and primer RT–cDNA, yielded a 2.9-kb DNA band (Fig. 1B, lane 6) that included the full-length tap and tpg gene sequences (data not shown).

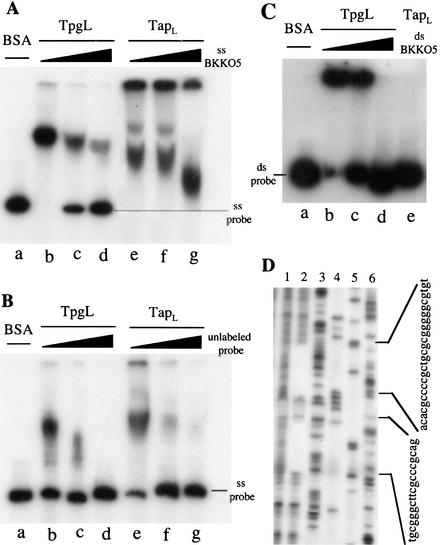

DNA-binding properties of the Tap and Tpg proteins

As protein-primed initiation of DNA chains de novo leaves an amino acid of the primer linked to the first nucleotide of the nascent DNA chain (Salas 1991; Yoo and Ito 1991; van der Vliet 1995; Hay 1996; Meijer et al. 2001), a priming role for terminal proteins of Streptomyces linear replicons has been inferred from their covalent attachment to the 5′ ends of these DNAs (Hirochika and Sakaguchi 1982; Kinashi et al. 1987; Sakaguchi 1990; Lin et al. 1993; Bao and Cohen 2001; Yang et al. 2002). However, the mechanism that positions terminal proteins at telomere termini for their priming function has not been known. To investigate a possible role for Tap in this process, we expressed the Tpg and Tap proteins in S. lividans as His6-tag fusion products, purified the fusion proteins as described in Materials and Methods, and used an electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA) procedure to test the ability of each purified protein to interact with telomeric DNA sequences. As seen in Figure 2A, migration of [α-32P]-labeled single-stranded DNA corresponding to the 3′ overhang of plasmid pSLA2 telomeres was retarded by both Tpg and Tap. However, the binding of Tpg showed little specificity and was largely reversed by the addition of excess denatured DNA of S. lividans BKKO5 (Bao and Cohen 2001), which has a circular chromosome and lacks telomeres (Fig. 2A, lanes b–d). In contrast, binding of Tap to single-strand telomeric DNA was highly specific and was not affected detectably by even a 100-fold excess of denatured DNA from BKKO5 (Fig. 2A, lanes e–g). Quantitatively, Tap interacted with the [α-32P]-labeled single-strand telomeric 3′ overhang DNA sequence 10 times more tightly than Tpg (Ka = 1 × 107 M−1 vs. Ka = 1 × 106 M−1, respectively), as determined by binding studies that used unlabeled probe as competitor (Fig. 2B). Although Tpg interacted additionally with double-strand telomeric DNA, this binding also was nonspecific and was inhibited by an excess of native BKKO5 DNA (Fig. 2C).

Figure 2.

DNA binding activity and footprinting analysis. (A) EMSA using radioactively labeled single-stranded pSLA2 telomeric DNA. (Lane a) Probe + BSA as control. (Lanes b,c,d) TpgL protein with 5-fold, 20-fold, and 100-fold excesses of single-stranded BKKO5 DNA. (Lanes e,g,f) Same as lanes b, c, and d except TapL protein was used. (B) EMSA using radioactively labeled single-stranded pSLA2 telomeric DNA in the presence of unlabeled cold probe as competitor. (Lane a) Probe + BSA as control. (Lanes b,c,d) TpgL protein with 5-fold, 20-fold, and 100-fold excesses of single-stranded cold probe. (Lanes e,g,f) Same as lanes b, c, and d except TapL protein was used. (C) EMSA using radioactively labeled double-stranded pSLA2 telomeric DNA. (Lane a) Probe + BSA as control. (Lanes b,c,d) TpgL protein with 5-fold, 20-fold, and 100-fold excesses of circular chromosomal DNA of BKKO5. (Lane e) TapL protein alone. (D) DNase I footprinting analysis using single-stranded pSLA2 telomeric DNA and TapL protein was carried out as described in Materials and Methods. (Lanes 1,2) Single-stranded telomeric DNA was incubated with 0 and 2 μg of TapL protein, respectively. (Lanes 3–6) DNA sequencing ladder reactions with termination mix of ddG, ddA, ddT, and ddC. Brackets at the right show two regions of the protected DNA sequences.

DNase I footprinting using Tap protein identified two distinct sites of single-strand DNA on the telomeric 3′ overhang of pSLA2 that were protected by the binding of Tap protein (Fig. 2D). One Tap-protected locus consists of 18 nt (TGCGGGCTTCGCCCGCAG) beginning at a thymidine positioned 17 nt from the telomere end; the second region extends 26 nt (ACACGCCCCGCTGC GCGGGGGCGTGT) from an adenosine located 40 nt from the end. Both of these Tap-protected DNA sequences previously were shown to be required for linear replication of pSLA2 derivatives (Qin and Cohen 1998), and both are highly conserved in all nine telomeric DNAs cloned from Streptomyces linear plasmids and chromosomes (Huang et al. 1998; Qin and Cohen 1998).

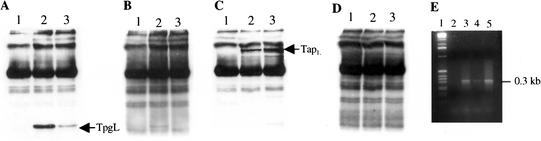

Tap and Tpg interact and form a telomere-associated complex

The ability of Tap to bind tightly and site-specifically to sequences in the telomeric 3′ overhangs of Streptomyces linear replication intermediates and the limited binding specificity of Tpg for this DNA region suggested that Tap may position Tpg to prime the synthesis of 5′ ends of lagging-strand DNA. As seen in Figure 3, immunoprecipitation and immunodepletion experiments using anti-Tap or anti-Tpg antibodies (see Materials and Methods) indicated that the Tap and Tpg proteins interact with each other in vivo. Tpg was detected by Western blotting in pellets immunoprecipitated by anti-Tap antibody (Fig. 3A, lane 3), and conversely, Tap was found in pellets immunoprecipitated by anti-Tpg antibody (Fig. 3C, lane 2). As seen in Figure 3C, addition of purified Tap or Tpg protein resulted in depletion of the ability of the respective antibody to react with its intended target, confirming the specificity of the antibody and the identity of the bands designated in the figure as Tap or Tpg.

Figure 3.

Tap coimmunoprecipitates with Tpg. (A–D) Streptomyces lividans 1326 cell extracts were incubated with prebleeding sera (lane 1), anti-TpgL antibodies (lane 2), and anti-TapL antibodies (lane 3). (A) Western blotting using anti-TpgL antibodies. (B) Immunodepletion analysis of lanes shown in A using anti-TpgL antibodies. (C) Western blotting using anti-TapL antibodies. (D) Immunodepletion analysis of lanes shown in C using anti-TapL antibodies. (E) Agarose gel electrophoresis of the products of IP–PCR using different immunoprecipitates as templates and the telomere-specific primers P-end and P300 (Materials and Methods). (Lane 1) 1-kb DNA ladder. (Lane 2) IP with prebleeding anti-sera as negative control. (Lane 3) IP with anti-TpgL. (Lane 4) IP with anti-TapL. (Lane 5) Template of total DNA of S. lividans 1326 as positive control.

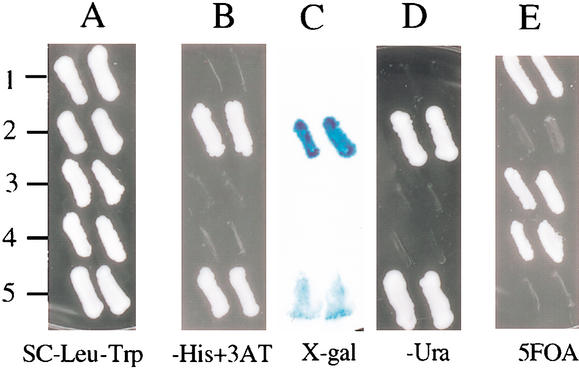

Interaction between Tap and Tpg proteins was further confirmed by yeast two-hybrid analysis (Fig. 4). In the latter studies, a Tap fusion to the GAL-4 DNA-binding domain was constructed (construct pBC191) and tested for interaction with Tpg fused to the GAL-4 activation domain (construct pBC193). The cotransformants of pBC191 and pBC193 (Fig. 4, row 5) and the positive control (Fig. 4, row 2) all showed induced expression of the three reporter genes used in the analysis, whereas reporter gene expression was not detected in cells cotransformed with the negative control [vectors pDBLeu + pDEST22 (Fig. 4, row 1), pBC191 + pDEST22 (Fig. 4, row 3), and pBC193 + pDBLeu (Fig. 4, row 4)].

Figure 4.

Yeast two-hybrid analysis of TapL and TpgL. Selection plates of SC-Leu-Trp (A), SC-Leu-Trp-His + 3AT (B), X-gal (C), SC-Leu-Trp-Ura (D), and SC-Leu-Trp + 0.2% 5FOA (E) were used to examine reporter gene phenotypes of yeast strain MaV203. (Row 1) Cotransformants of pDBLeu and pDEST22 as negative control. (Row 2) Cotransformants of pPC97-Fos and pPC86-Jun as positive control. (Row 3) Cotransformants of pBC191 and pDEST22. (Row 4) Cotransformants of pBC193 and pDBLeu. (Row 5) Cotransformants of pBC191 and pBC193.

PCR analysis of proteinase K-treated anti-Tpg or anti-Tap immunoprecipitates using the telomere-specific primers P-end and P300 (see Materials and Methods) indicated the presence of telomeric DNA in both types of immunoprecipitates (Fig. 3E, lanes 3,4), whereas control PCR analyses using primers corresponding to two separate regions of nontelomeric DNA failed to generate the appropriate-sized PCR amplicons (data not shown).

Tap is essential for propagation of Streptomyces chromosomes and plasmids in linear form

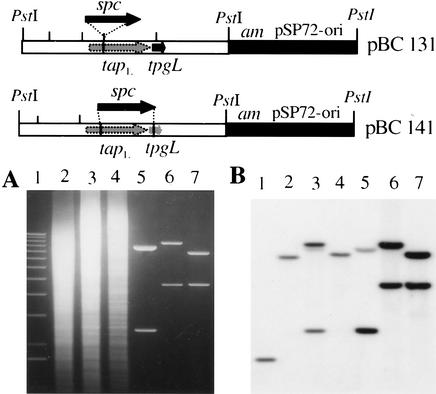

Is Tap essential for linear DNA replication in Streptomyces? To investigate the effects of inactivation of tap, we used a gene-replacement/disruption procedure that introduced a spectinomycin-resistance (Spcr) gene into the chromosomal tap gene (Fig. 5). Because the tap and tpg genes are cotranscribed, and we wished to obtain an S. lividans isolate defective only in tap, we performed the tap disruption in a strain that contained a plasmid expressing tpg from an adventitious promoter. Southern blot analysis confirmed replacement of the native tap locus with an allele containing the Spcr insert (BKKO17; Fig. 5A,B). In analogous experiments, we used a similar gene-replacement strategy to disrupt both the tap and tpg genes, using plasmid pBC141, which contains fragments of tap and tpg that are colinear with the chromosome but separated by Spcr (Fig. 5, top). The double knockout of tap and tpg was confirmed by Southern blot analysis (BKKO19, Fig. 5A,B).

Figure 5.

Analysis of Streptomyces lividans 1326 chromosomal DNA showing disruption of tapL gene and both tapL and tpgL. (Top) Schematic representation of gene disruption. tapL was disrupted by an in-frame insertion of spc on pBC131; both tapL and tpgL were disrupted by the replacement of spc on pBC141. am, apramycin-resistance gene; spc, spectinomycin-resistance gene. (A) Ethidium bromide-stained agarose gel. (Lane 1) 1-kb DNA ladder. (Lane 2) 1326 total DNA. (Lane 3) BKKO17 total DNA. (Lane 4) BKKO19 total DNA. (Lane 5) pBC117 plasmid DNA. (Lane 6) pBC141 plasmid DNA. (Lane 7) pBC129 plasmid DNA. (B) Southern blot of same gel probed with 32P-labeled pBC141. All DNAs were digested with PstI.

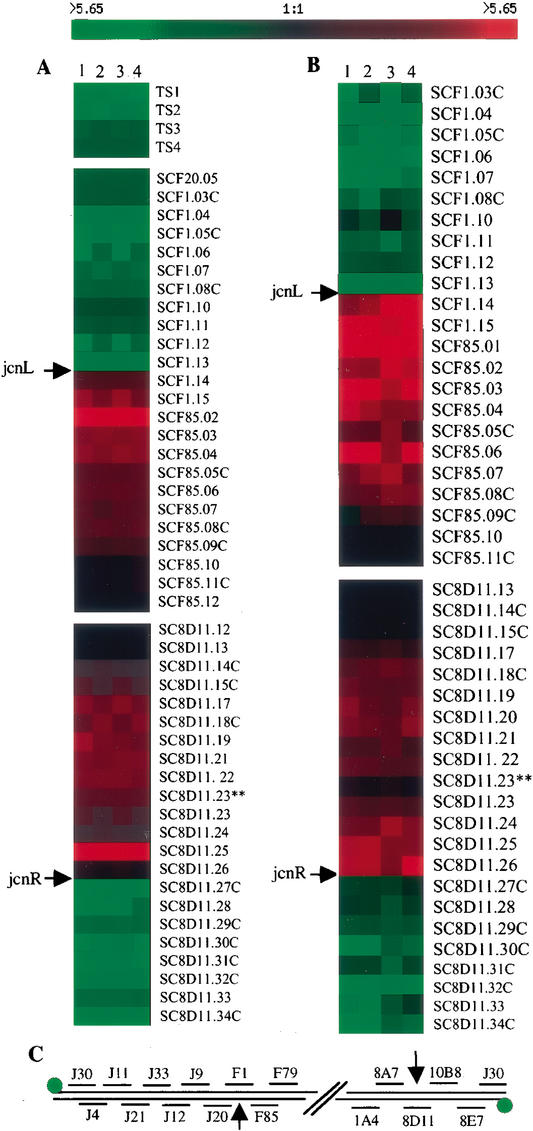

Southern blots of DNA isolated from the tap insertion mutant BKKO17 or from the doubly mutated tap− tpg− strain BKKO19 using telomeric DNA as a probe (data not shown) suggested that the clones surviving tap mutation had undergone telomere deletion. Telomere deletion was confirmed, and the endpoints of deletions in BKKO17 and BKKO19 were mapped at single-gene resolution by using whole-genome DNA microarrays from S. coelicolor (Fig. 6; Huang et al. 2001), a close relative of S. lividans. In these experiments, preparations of total DNA from mutant and wild-type S. lividans strains were differentially labeled with fluorescent dyes as described in Materials and Methods and hybridized concurrently to microarray slides. The relative hybridization of mutant and wild-type probes was assessed as described for Streptomyces RNAs (Huang et al. 2001). Data were analyzed by the GABRIEL program's continuity/gap algorithm (Huang et al. 2001; Pan et al. 2002) using the S. coelicolor genomic DNA sequence reported by Bentley et al. (2002). This analysis (Fig. 6) showed DNA deletion (depicted by green) at both chromosomal ends for each strain, identified the ORFs that were deleted in BKKO17 and BKKO19, and defined the deletion endpoints at single-ORF resolution. In both strains, the endpoint of the deletion that removed the telomeres occurred within a 500-bp DNA region located between ORF SCF1.13 and ORF SCF1.14 (indicated by jcnL in Fig. 6A,B) at the “left” end of the chromosome [according to the orientation of Redenbach et al. (1996) as reported by Bentley et al. (2002)] and within a 380-bp segment between ORF SC8D11.26 and ORF SC8D11.27c (indicated by jcnR) at the “right” end.

Figure 6.

Whole-genome comparison of knockout strain BKKO17 (tapL−) or BKKO19 (tapL− tpgL−) with wild-type Streptomyces lividans 1326. Profiles indicate gene deletion and amplification in knockout strains. Genes were analyzed and clustered by GABRIEL analysis (Pan et al. 2002). Consistency in the amount of DNA used for analysis at different repeats was inferred from our finding that 97% of the genes analyzed showed no change in the compared strains. DNA ratios are represented in tabular form according to the color scale shown at the top; rows correspond to individual genes, and columns correspond to different repeats. Green shades represent gene deletion in knockout strain, and red shades represent gene amplification in knockout. Black indicates unchanged ORFs in the comparing DNA. jncL, junction of the left chromosome end; jncR, junction of the right chromosome end. Lanes 1–4 represent 4 repeats. (A) Profile of the comparison of BKKO17 and S. lividans 1326. TS1, 2, 3, and 4, telomere sequences 1, 2, 3, and 4. Chromosomal telomere DNA was PCR-amplified and printed on the DNA microarray slides for detecting telomere loss. (B) Profile of the comparison of BKKO19 and S. lividans 1326. (C) The ordered cosmids at two chromosomal ends (Redenbach et al. 1996). Green dots represent terminal protein covalently bound to chromosome end. Black arrows point to the chromosomal breakpoints.

Streptomyces plasmids and chromosomes require telomeres to replicate as linear molecules, but can replicate in a circular form following telomere loss (Shiffman and Cohen 1992; Chang and Cohen 1994; Chang et al. 1996; Lin et al. 1993; Lin and Chen 1997; Volff et al. 1997; Qin and Cohen 1998, 2002; Volff and Altenbuchner 2000). The above results thus imply that the telomere-deleted chromosomes of the Tap knockout isolates BKKO17 and BKKO19 had circularized, as observed previously in cells that survive mutation of the tpg gene (Bao and Cohen 2001). Chromosome circularization in these isolates was confirmed by sequencing cloned PCR-generated DNA fragments containing the junction between the two deletion endpoints. The cloned 2.1-kb junction fragment of BKKO17 showed at one end a 627-bp DNA sequence matching the ORF SCF1.13 sequence. At the other end was a 589-bp sequence matching ORF SC8D11.26, a 35-bp intergenic region, and a 342-bp sequence corresponding to the C-terminal sequence of ORF SC8D11.27c. The DNA sequences of ORFs SCF1.13 and SC8D11.26, which normally are located at separate ends of the linear chromosome, were found also on the cloned ∼2.0-kb junction fragment of BKKO19. An adventitious 935-bp DNA segment containing two incomplete consecutive ORFs (SC5H4.15, putative secreted sugar hydrolase; and SC5H4.16c, putative transcriptional regulator), that map to the central portion of the linear S. lividans chromosome was inserted between the joined chromosomal DNA ends of BKKO17. BKKO19 contained a 445-bp sequence of pBC141 vector DNA inserted between the joined chromosome ends. Analogous insertions of adventitious DNA previously have been discovered between the ends of plasmids circularized by nonhomologous end joining (NHEJ) in Streptomyces (Qin and Cohen 2002), and at the junctions of recombined nonhomologous linear DNAs of other organisms (e.g., Moore and Haber 1996; Gorbunova and Levy 1997; Yu and Gabriel 1999).

In both BKKO17 and BKKO19, amplification of a segment of contiguous genes located immediately adjacent to the point of breakage was observed by microarray analysis (Fig. 6A,B, indicated by red color), consistent with earlier Southern blot data (Volff et al. 1997) showing gene amplification in an S. lividans strain having a circular chromosome. The region of amplified ORFs in both BKKO17 and BKKO19 (Fig. 6A,B, genes shown in red) extends for ∼9500 bp (from ORFs SCF1.14–SCF85.08c) from the deletion endpoint at the left chromosome end, and shows an estimated five to six copies of each gene based on the relative intensity of fluorescence of mutant strain versus wild-type DNA in microarray spots. The amplified ORFs at the right-end chromosome junctions of BKKO17 and BKKO19 are different: ∼5200 bp from ORFs SC8D11.17 to SC8D11.23** were amplified in BKKO17 and ∼8400 bp from ORFs SC8D11.17 to SC8D11.26 were amplified in BKKO19. In both cases, amplified genes are estimated to exist at two to three copies per chromosome. ORFs located internal to the amplified segment showed similar hybridization with differentially labeled DNA from BKKO17 or BKKO19 when compared with DNA from the parental (linear chromosome) strain (Fig. 6A,B, ORFs represented by black).

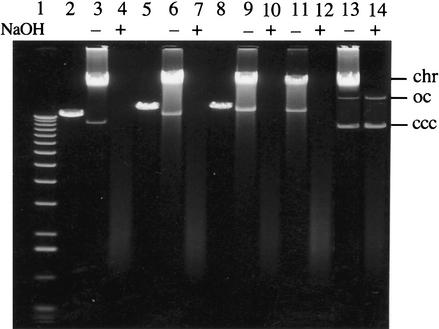

The above experiments strongly support the argument that Tap is required for the propagation of Streptomyces chromosomes in a linear form. To learn whether the same is true for plasmid replicons, pSLA2-derived plasmids that include the Escherichia coli plasmid pSP72 replicon and also contain the S. lividans tpg gene (pBC167), the tap gene (pBC178), or both genes (pBC181) were constructed as described in Materials and Methods and cloned in E. coli. In Figure 7, lanes 2, 5, and 8 contain DNA of plasmids pBC167, pBC178, and pBC181, respectively, isolated from E. coli and linearized by cleavage at the SspI site of pSP72. Introduction of these SspI-cleaved DNAs into S. lividans 1326, which contains intact chromosomal tpg and tap genes, yielded viable transformants at a frequency of 5 × 102/μg of DNA. These transformants all contained linear plasmids (Fig. 7; shown in lanes 3,6,9 for typical transformants receiving each plasmid), in agreement with previous evidence that such plasmid DNAs can generate linear replicons when introduced into S. lividans by transformation (Shiffman and Cohen 1992; Qin and Cohen 1998, 2000; Bao and Cohen 2001). The linearity of the replicons isolated from transformants was confirmed by alkaline lysis (Qin and Cohen 1998, 2000), which removes both linear plasmid DNA and fragments of chromosomal DNA (Fig. 7, cf. lanes 4,7,10 and 3,6,9). Only plasmid pBC181, which carries cloned tap and tpg genes, yielded transformants after SspI cleavage and introduction by transformation into BKKO19—which lacks the chromosomal tap and tpg genes. Linearity of the plasmids propagated in these transformants was shown by their sensitivity to alkaline lysis (Fig. 7, cf. lanes 11 and 12). We conclude that both tap and tpg are essential for replication of linear plasmid DNA as well as chromosomal DNA in a linear form in S. lividans.

Figure 7.

Analysis of plasmid DNA replication of pSLA2 derivatives (pBC167, pBC178, and pBC181) in Streptomyces lividans 1326 and in the tapL and tpgL double-knockout strain BKKO19 (with a circular chromosome). pBC167 contains a functional tpgL gene, pBC178 contains a functional tapL gene, and pBC181 contains both tpgL and tapL. Streptomyces linear plasmid DNA was isolated from 1326 and BKKO19 transformants by treatment with proteinase K and SDS (Qin and Cohen 1998, 2000) and was electrophoresed for 12 h at 30 V in a 0.6% agarose gel; linear samples indicated by + were isolated by an alkaline lysis procedure (incubation in 0.2 N NaOH at 37°C for 30 min) followed by phenol/chloroform extraction to remove or degrade linear plasmids and chromosomal DNA fragments (Qin and Cohen 1998, 2000). (Lane 1) 1-kb DNA ladder. (Lane 2) SspI-digested pBC167 plasmid DNA isolated from Escherichia coli. (Lane 3) DNA isolated from a 1326 transformant receiving SspI-cleaved pBC167. (Lane 4) Same DNA as in lane 3, but following NaOH treatment. (Lane 5) SspI-digested pBC178 plasmid DNA. (Lane 6) DNA isolated from a 1326 transformant receiving SspI-cleaved pBC178. (Lane 7) Same DNA as in lane 6, but following NaOH treatment. (Lane 8) SspI-digested pBC181 plasmid DNA. (Lane 9) DNA isolated from a 1326 transformant receiving SspI-cleaved pBC181. (Lane 10) Same DNA as in lane 9, but following NaOH treatment. (Lane 11) DNA isolated from a BKKO19 transformant receiving SspI-cleaved pBC181. (Lane 12) Same DNA as in lane 11, but following NaOH treatment. (Lane 13) The banding positions of chromosomal (chr) and plasmid (ccc, covalently closed circular; OC, open circular) DNAs isolated from BKKO19 transformants receiving uncleaved pBC178 DNA. (Lane 14) The bands that were recovered from lane 13 DNA following NaOH treatment.

Discussion

Because of the 5′-to-3′ polarity of DNA replication, the propagation of all linear replicons requires a solution to the “end replication problem,” that is, the need to provide both a template and primer for DNA synthesis at telomeres (Watson 1972; Kornberg and Baker 1992). Eukaryotes have evolved a strategy that uses an RNA template and the riboenzyme telomerase for telomeric DNA synthesis (for review, see McEachern et al. 2000; Blackburn 2001). For B. subtilis bacteriophage φ29, E. coli phage PRD1, and the adenoviruses of mammalian cells, the end replication problem is solved by a mechanism of strand-displacing protein-primed synthesis of the full-length genome (Salas 1991; Yoo and Ito 1991; van der Vliet 1995; Hay 1996; Meijer et al. 2001). Still other linear replicons have evolved mechanisms of “turn-around” replication to accomplish lagging-strand DNA synthesis and consequently contain a single-strand loop located between inverted repeat sequences at the ends of duplex DNA (for review, see Kornberg and Baker 1992). As Streptomyces linear plasmids and chromosomes are known to initiate replication bidirectionally from a internal site near the center of the molecule (Shiffman and Cohen 1992; Chang and Cohen 1994; Musialowski et al. 1994), producing replication intermediates that contain a 3′ overhang of leading-strand DNA (Chang and Cohen 1994), their telomeres must undergo patching to generate blunt-ended postreplicative DNA molecules. Because deletion of widely spaced palindromic DNA sequences in the telomeres of Streptomyces linear plasmids precludes plasmid DNA replication in a linear form, it has been proposed that pairing of sequences of the 3′-leading-strand overhang with internal sequences near the base of the overhang provides a recognition site for DNA-binding proteins involved in telomere patching (Qin and Cohen 1998, 2000). The data reported here indicate that the function of Tap is central to telomere function in Streptomyces, and further suggest that Tap's dual interactions with Tpg and specific sequence of the 3′-leading-strand overhang can position Tpg to prime synthesis of the lagging-strand 5′ terminus. S. lividans bacteria require a functional tap gene to propagate chromosomal and plasmid DNA in a linear form, and cells that survive after disruption of tap show telomere deletion and recombinational circularization of the chromosome.

The Tpg protein, which is attached covalently to 5′ DNA ends of Streptomyces linear replicons, protects these ends from degradation by exonucleases (Hirochika and Sakaguchi 1982; Hirochika et al. 1984; Lin et al. 1993; Chang and Cohen 1994). The telomere-binding properties of Tap parallel those of eukaryotic proteins that interact with 3′ overhangs of replication intermediates and protect DNA ends from degradation (e.g., Garvik et al. 1995; Baumann and Cech 2001; Blackburn 2001; Pennock et al. 2001; Baumann et al. 2002). It has not been determined whether Tap also has a role in protecting Streptomyces linear chromosomes and linear plasmids from initiating an SOS-like response (Volff et al. 1993a,b; ZakrzewskaCzerwinska et al. 1994; Sutton et al. 2000) or in interfering with degradation of the 3′ termini of replicative intermediates.

It is well recognized that the chromosomes of Streptomyces spp. show extensive genetic instability (for review, see Volff and Altenbuchner 1998, 2000; Chen et al. 2002), and in particular that very large deletions can be accompanied by high-copy-number tandem amplification of flanking DNA (Redenbach et al. 1993; for reviews, see Leblond and Decaris 1994; Dary et al. 2000; Chen et al. 2002). Experimentally induced circularization of the S. lividans chromosome by a targeted recombination procedure can enhance genetic instability and genome rearrangement (Lin and Chen 1997; Volff et al. 1997). Commonly, DNA cloning, PCR, and Southern blot hybridization have been used to identify endpoints of deletions in genomic DNA as well as the extent of gene amplification (Lin and Chen 1997; Volff et al. 1997). In the investigations reported here, we have instead used a map of the genomic sequence of S. coelicolor (Bentley et al. 2002; http://www.sanger.ac.uk/Projects/S_coelicolor) together with DNA microarray analysis and algorithms of the GABRIEL knowledge-based program (Pan et al. 2002; http://gabriel.stanford.edu) to more readily investigate these parameters. This approach has identified hotspots that define endpoints for telomere deletion and DNA amplification at single-ORF resolution in independent circularization events and—consistent with earlier work using more traditional methods of analysis (Lin and Chen 1997; Volff et al. 1997)—has demonstrated that that amplification of subtelomeric DNA at both ends occurs in a region immediately proximate to the deletion endpoint. Whether such amplification has a role in maintaining chromosome function or is simply a consequence of telomere loss and chromosome circularization is not known.

Materials and methods

Bacterial strains, plasmids, and general methods

S. coelicolor M145 and S. lividans 1326 (Hopwood et al. 1983) were kindly provided by D.A. Hopwood (John Innes Centre, Norwich, UK). S. rochei 7434-AN4 (Hirochika and Sakaguchi 1982) was kindly provided by K. Sakaguchi (Mitsubishi-Kasei Institute of Life Sciences, Tokyo, Japan). Streptomyces–E. coli shuttle plasmid pHZ1272, which was used for gene expression in Streptomyces, was kindly provided by Z. Deng, Shanghai Jiaotong University, Shanghai, P.R. China (pers. comm.). E. coli DH5α (Invitrogen Life Technologies) and pSP72 (Promega) were used as the E. coli host and cloning vector, respectively. Standard methods were used for culturing cells, DNA cloning, and so on in E. coli (Sambrook and Russell 2001), Streptomyces (Kieser et al. 2000), and yeast (Kaiser et al. 1994). Restriction-enzyme-digested DNA fragments were extracted from agarose gel by Qiaquick Gel Extraction Kit (QIAGEN). Southern blot hybridization used the procedure of Church and Gilbert (1984). DNA sequencing was performed using an Applied Biosystems (ABI) Prism 310 Genetic Analyzer and ABI dye terminator sequencing kit. DNA sequencing was carried out for both strands. Linear plasmid DNA was isolated as described by Qin and Cohen (1998).

Reverse transcriptase (RT)–polymerase chain reaction (PCR) experiments

RT–PCR was used to check cotranscription of tapL and tpgL. Total RNAs were prepared from 36-h mycelium of S. lividans 1326 by modified Kirby mix, phenol/chloroform extraction (Kieser et al. 2000), and DNase I (Worthington, DPRFS grade) treatment. The same amount of total RNA was then used for each reaction in a first-strand cDNA synthesis reaction using primer RT–cDNA: AACTCCAGGTGCTCGATGTCCGTGAA and Superscript II reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen Life Technologies). The cDNAs were then PCR-amplified by HotStar Taq DNA polymerase (QIAGEN) using five specific pairs of primers as follows: RT–cDNA and RT_0.6kb, ACGCCGACAGCGGAG AGTAGGA; RT–cDNA and RT_1.3kb, GTGAAGGTGGGCA AGGAGTGGG; RT–cDNA and RT_2.0kb, GCGCACTGGA AGCTGACGAAGC; RT–cDNA and RT_2.4kb, GTACTTGC CGCCGTGCCTTCCG; and RT–cDNA and RT_2.9kb, ATCA GGGCCTGAATTCCTCCCA. To control for genomic DNA contamination, cDNA synthesis reactions were also done in the absence of the RT. No PCR product was observed with the first pair of primers: RT–cDNA and RT_0.6kb, ACGCCGACAGC GGAGAGTAGGA in the absence of RT.

Purification of fusion proteins and generation of antibodies

The tapL gene sequence was amplified from cosmid pBC30 of genomic DNA library of S. lividans ZX7 (Bao and Cohen 2001) by PCR using a HotStar Taq DNA polymerase (QIAGEN) and a pair of primers, 5′-AAACATATGCATCATCATCATCATCA TGTGTCCGGTAGAGGAGCGCAG-3′ and 5′-GCCGTTGCC GAACAGGCTCAT-3′, and was introduced into TA cloning vector pCR2.1 (Invitrogen Life Technologies) as plasmid pBC171. The correctness of the construct was confirmed by DNA sequence analysis. The tapL gene was further cloned into NdeI–EcoRI-digested pHZ1272 from pBC171 (as plasmid pBC172), which enabled production of a fusion protein containing a histidine tag at the N-terminal end in S. lividans 1326. The tpgL was similarly cloned into NdeI–EcoRI-digested pHZ1272 (as plasmid pBC156) using the primer pair 5′-AATTCATATGCAT CATCATCATCATCATATGAGCCTGTTCGGCAACGGC-3′ and 5′-GCCTGGAACGTCACCGTCCTACAG-3′ for overexpression of TpgL in S. lividans 1326. After induction (10 μg/mL thiostrepton) at 30°C for 12 h, cells of S. lividans 1326 containing pBC172 or pBC156 were harvested and resuspended in 50 mM NaH2PO4 (pH 7.5), 300 mM NaCl, 10 mM imidazole, 10% glycerol, 0.2% Triton X-100, 5 mM β-mercaptoethanol, and 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (PMSF) for lysis by French Press (pressure at 1000 kg/cm2). DNA in the lysis mixture was sheared by sonication, and cell debris was removed by centrifugation (39,000g for 20 min). The TapL/TpgL fusion protein, whose components were confirmed by Western blot analysis using His-tag gel antibody, was further purified by Ni2+-column chromatography (QIAGEN). TapL was eluted around 100 mm imidazole and TpgL was eluted around 150 mM imidazole. The fusion protein-containing fractions were dialyzed against H buffer (50 mM HEPES at pH 7.5, 10% glycerol, 50 mM KCl, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM PMSF, and 1 mM dithiothreitol) and were further purified on a Heparin column (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech) using a linear gradient of KCl (0.1–1.0 M) at 4°C. TapL was eluted at 0.6 M KCl, and TpgL was eluted at 0.4 M KCl. The proteins were dialyzed against H buffer plus 100 mM KCl and used for electrophoretic mobility shift assays and for the production of rabbit anti-TapL and anti-TpgL polyclonal antibodies (Covance Research Products), respectively. Antisera from the rabbit were first screened for protein binding using an ELISA assay; positive antisera were then tested for specificity on Western analysis and further purified by a protein A column (Pierce).

Electrophoretic mobility shift assays (EMSA) and footprinting analysis

Double-stranded 365-bp telomeric DNA of pSLA2 was gel-purified from BglII–XbaI-digested pQC5 (Qin and Cohen 1998) and end-labeled with [α-32P]dCTP and DNA polymerase Klenow fragment (Invitrogen Life Technologies). Labeled DNA was separated from free [α-32P]dCTP by filtration through a MicroSpin S-400 HR column (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech Inc). Labeled double-stranded DNA probe was denatured at 100°C for 10 min and then immediately put into an ice-cold waterbath and used as a single-stranded DNA probe in EMSA. The DNA-binding reaction was performed at 25°C for 1 h using 0.5 nM radiolabeled DNA probe, 100 nM purified TpgL or TapL and the binding buffer (20 mM Tris at pH 8.0, 1 mM EDTA, 100 mM NaCl, 5% glycerol, 2 mM DTT) supplemented with 50 μg/mL double- or single-stranded salmon sperm DNA in a final volume of 20 μL. Competition was accomplished by adding 5-fold, 20-fold, and 100-fold excess of sonicated circular chromosomal DNA of BKKO5 (Bao and Cohen 2001) or 5-fold, 20-fold, and 100-fold excess of cold probe to the binding reaction. The DNA–protein complexes were separated on prerun 5% Tris-borate-EDTA (TBE) native acrylamide gels in 0.5× TBE buffer at 200 V for 3 h. Gels were dried and exposed to X-ray film at −80°C. The DNase I footprinting method for identifying protein-binding sites on DNA (Galas and Schmitz 1978) was modified as follows: DNA–protein-binding reactions were carried out as described as above. CaCl2 and MgCl2 were added to final concentrations of 2.5 and 5 mM, respectively, and 1 μL DNase I (10 μg/mL) was added. After incubation at room temperature for 1 min, an equal volume of stop buffer (1% SDS, 20 mM EDTA, 300 mM NaCl, and 2 mg/mL yeast tRNA) was added. The mixtures were extracted with phenol/chloroform, ethanol-precipitated, and separated on an 8% denaturing polyacrylamide gel. A DNA ladder showing the sequence of the region footprinted was prepared using a chain-terminating reaction (USB, Sequenase 7-deaza-dGTP sequencing kit) and an oligonucleotide primer complementary to the 3′ end of the probe fragment. The reaction products were separated by electrophoresis in a gel alongside of the footprinting reaction mixture to identify nucleotide bonds protected by the binding of Tap.

Western, immunoprecipitation (IP), immunodepletion, and IP-PCR analysis

Western and immunoprecipitation (IP) analysis were performed according to the procedures of Harlow and Lane (1988). S. lividans 1326 cell extracts were made for IP analysis in Nonidet P-40 (0.5%) buffer (Harlow and Lane 1988) using a French Press (1000 kg/cm2) and then sonication. The immunoprecipitate of TpgL antibody was treated with DNase I (Worthington, DPRFS grade) for Western blotting against TpgL antisera. Chemiluminescence Reagent Plus (PerkinElmer NEN Life Sciences) was used for detection in immunoblotting. The immunoblotted membrane was stripped by Restore Western Blot Stripping Buffer (Pierce) and then used for immunodepletion analysis. In immunodepletion experiments, the primary antibody (anti-TpgL or anti-TapL antisera, 1:2000 dilution) was incubated with the relevant antigen (purified TpgL or TapL from S. lividans; i.e., TapL) in PBST buffer with 5% milk at 4°C for 12 h and then was used as the primary antibody for the second round of immunoblotting chemiluminescence detection. For IP-PCR analysis, a pair of primers (P-end, 5′-CCCGCGGAGCGGG TACCCTATCGCT-3′ and P-300, 5′-CGAGCCCCGGTCCCT GTAGGCGCTC-3′) was designed to amplify the 300-bp chromosome end of S. lividans 1326. Template DNA was isolated from immunoprecipitate after being treated with proteinase K and was then extracted with phenol/chloroform.

Yeast two-hybrid analysis

The yeast two-hybrid assay was carried out according to ProQuest Two-Hybrid System with Gateway Technology (Invitrogen Life Technologies). Two primers containing attB1 and attB2 were designed to amplify the tpgL gene as follows: attB1_tpgL_5′, 5′-GGGGACAAGTTTGTACAAAAAAGCAGGCTAGATGAGC CTGTTCGGCAACGGC-3′ and attB2_tpgL_3′, 5′-GGGGACA CTTTGTACAAGAAAGCTGGGTCCTACAGGTCGAACTC CAGGTG-3′. The PCR product of the tpgL gene was cloned into the Entry Vector and then transferred into pDEST22 containing GAL4-AD (prey vector) as plasmid pBC193 by Gateway Cloning Technology (Invitrogen Life Technologies). GAL4-DB-tapL was constructed by subcloning an NcoI and NotI fragment of tapL from pBC162 (tapL on pET28a) into the same enzyme-digested GAL4-DB plasmid pDBLeu (bait vector), as plasmid pBC191. All constructs were verified by DNA sequencing to confirm identity and reading frame. The expression of GAL4 fusion proteins was confirmed by Western blotting analysis against anti-TpgL or anti-TapL antisera. Plasmids pBC191 and pBC193, pBC191 and pDEST22, and pBC193 and pDBLeu were cotransformed into host yeast strain MaV203. Cotransformants were screened and selected on yeast minimal medium SC-Leu-Trp plates and used for testing interactors for the induction of reporter genes on SC-Leu-Trp-His plates containing 20 mM 3-AT (3-aminotriazole, Sigma), SC-Leu-trp-Ura plates, SC-Leu-trp + 0.2% 5FOA (5-fluoroorotic acid, Sigma) plates, and X-gal assay plates.

Gene disruption and complementation

A tapL gene-disruption plasmid (pBC131, see Fig. 5) was constructed by inserting a spectinomycin-resistance gene (spcr) at the Eco47III site of the tapL gene following partial digestion of the tapL fragment cloned in E. coli. Another gene-disruption plasmid (pBC141, see Fig. 5) was also constructed for the replacement of tapL and tpgL with a spectinomycin-resistance gene. Because tapL and tpgL are cotranscribed (see RT–PCR result in Fig. 1), in order to mutate the tapL gene of S. lividans 1326, plasmid pBC117 carrying the tpgL gene at NdeI–BamHI sites of pHZ1272 (Zixin Deng, pers. comm.) was used to express TpgL in S. lividans 1326. Protoplasts of 1326(pBC117) were transformed with pBC131, which lacks the ability to replicate in Streptomyces and contains an apramycin-resistance gene, and transformants (spcr amr) were selected on R5 media containing spectinomycin. Clones in which a double crossover led to replacement of tapL by the insertionally mutated gene were isolated by testing spores for sensitivity to apramycin; this was done using replica plating of colonies selected in the presence of spectinomycin and in the absence of apramycin (spcr ams). Replacement of wild-type tapL by the insertionally mutated gene in spcr tsrs bacteria was confirmed by Southern blot hybridization. Replacement of both tapL and tpgL by spcr was accomplished by transforming pBC141 into S. lividans 1326. For gene complementation, tpgL, tapL, and tapL + tpgL were cloned into the NdeI–EcoRI sites of pHZ1272 as pBC166, pBC177, and pBC180, respectively. The BglII fragments of these three plasmids containing a functional Streptomyces promoter and each insert were then cloned into the pQC18-derived replicon pBC104 (Bao and Cohen 2001) to generate pBC167, pBC178, and pBC181, respectively. S. lividans 1326 and its derivative BKKO19 (tpgL− tapL−, see above) were transformed with the linearized DNA of pBC104, pBC167, pBC178, and pBC181. Transformants were analyzed for linear plasmid replication.

DNA microarray analysis

Construction of S. coelicolor M145 DNA microarrays was done as previously described (Huang et al. 2001). The complete genomic DNA sequence consisting of 7825 known and putative ORFs (ftp://ftp.sanger.ac.uk/pub/S_coelicolor/sequences) and a 30-kb chromosome end fragment (http://www.sanger.ac.uk/Projects/S_coelicolor) were used to design prime pairs for PCR amplification (protocol is available at http://sncohenlab.stanford.edu/streptomyces). Total DNA from S. lividans 1326 or from knockout strains BKKO17 (tapL−) or BKKO19 (tapL− tpgL−) was used as template, and incorporation of fluorescent nucleotide analogs Cy3-dCTP or Cy5-dCTP (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Inc.) in DNA was accomplished by a randomly primed DNA polymerase reaction. The labeling reaction (50 μL) contained 2 μg of template DNA, 5 μL of 10× buffer, 5 μL of dNTP mix (4 mM dATP, 4 mM dTTP, 10 mM dGTP, and 1 mM dCTP), 10 μg of 72% (G + C) content hexamers, 3 μL of Cy3-dCTP or Cy5-dCTP, and 2 μL of DNA polymerase Klenow fragment (Invitrogen Life Technologies). Labeled DNAs from the strains being compared were mixed together and purified through a GFX-column (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Inc.). Microarray hybridization and slide washing and scanning were performed as described previously (DeRisi et al. 1997; Behr et al. 1999). Microarray data analysis was performed with the software available at http://genome-www5.stanford.edu/MicroArray/SMD/restech.html and by GABRIEL, a knowledge-based machine learning computer program (Pan et al. 2002; http://gabriel.stanford.edu). PCR amplification of the junction fragments formed by chromosome circularization used two primers, JncL-SCF1.14 (5′-AGCAGCGGCCACAGGTAGTC-3′) and JncR-SC8D11.26 (5′-TGCTTGAGCCGACCGATGAG-3′), which are identical, respectively, to the right and left primers used for amplifying the PCR products of ORF SCF1.14 and ORF SC8D11.26 for DNA microarray analysis. The PCR products were then introduced into the TA cloning vector pCR2.1 (Invitrogen Life Technologies), and the inserted DNA was sequenced.

Acknowledgments

These investigations were supported by NIH grant AI08619 to S.N.C. We thank K.-H. Pan for carrying out GABRIEL analysis of the endpoints of chromosomal deletions and amplifications; Jeanette Lam, Jason Lih, and J.-Q. Huang for the construction of S. coelicolor M145 DNA microarrays; Zixin Deng for providing Streptomyces gene expression vector pHZ1272; and Haruyasa Kinashi for sharing his unpublished DNA sequence data. K.B. thanks Chris Miller, Annie Chang, C.-J. Lih, Z.-J. Qin, K.-H. Pan, T.-H. Cheng, J.-Q. Huang, Björn Sohlberg, Kangseok Lee, and Ronen Mosseri for helpful discussions.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by payment of page charges. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

Footnotes

E-MAIL sncohen@stanford.edu; FAX (650) 725-1536.

Article and publication are at http://www.genesdev.org/cgi/doi/10.1101/gad.1060303.

References

- Bao K, Cohen SN. Terminal proteins essential for the replication of linear plasmids and chromosomes in Streptomyces. Genes & Dev. 2001;15:1518–1527. doi: 10.1101/gad.896201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baumann P, Cech TR. Pot1, the putative telomere end-binding protein in fission yeast and humans. Science. 2001;292:1171–1175. doi: 10.1126/science.1060036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baumann P, Podell E, Cech TR. Human pot1 (protection of telomeres) protein: Cytolocalization, gene structure, and alternative splicing. Mol Cell Biol. 2002;22:8079–8087. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.22.8079-8087.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Behr MA, Wilson MA, Gill WP, Salamon H, Schoolnik GK, Rane S, Small PM. Comparative genomics of BCG vaccines by whole-genome DNA microarray. Science. 1999;284:1520–1523. doi: 10.1126/science.284.5419.1520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bentley SD, Chater KF, Cerdeno-Tarraga AM, Challis GL, Thomson NR, James KD, Harris DE, Quail MA, Kieser H, Harper D, et al. Complete genome sequence of the model actinomycete Streptomyces coelicolor A3(2) Nature. 2002;417:141–147. doi: 10.1038/417141a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bibb MJ, Findlay PR, Johnson MW. The relationship between base composition and codon usage in bacterial genes and its use for the simple and reliable identification of protein-coding sequences. Gene. 1984;30:157–166. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(84)90116-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blackburn EH. Switching and signaling at the telomere. Cell. 2001;106:661–673. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00492-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryan TM, Cech TR. Telomerase and the maintenance of chromosome ends. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 1999;11:318–324. doi: 10.1016/S0955-0674(99)80043-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Champness WC, Chater KF. Regulation and integration of antibiotic production and morphological differentiation in Streptomyces spp. In: Piggot P, Moran Jr. C, Youngman P, editors. Regulation of bacterial differentiation. Washington, DC.: American Society of Microbiology; 1994. pp. 61–93. [Google Scholar]

- Chang PC, Cohen SN. Bidirectional replication from an internal origin in a linear Streptomyces plasmid. Science. 1994;265:952–954. doi: 10.1126/science.8052852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang PC, Kim ES, Cohen SN. Streptomyces linear plasmids that contain a phage-like, centrally located, replication origin. Mol Microbiol. 1996;22:789–800. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1996.01526.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chater KF. Genetic regulation of secondary metabolic pathways in Streptomyces. Ciba Found Symp. 1992;171:144–156. doi: 10.1002/9780470514344.ch9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen CW. Complications and implications of linear bacterial chromosomes. Trends Genet. 1996;12:192–196. doi: 10.1016/0168-9525(96)30014-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen CW, Huang C, Lee H, Tsai H, Kirby R. Once the circle has been broken: Dynamics and evolution of Streptomyces chromosomes. Trends Genet. 2002;18:522–529. doi: 10.1016/s0168-9525(02)02752-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Church GM, Gilbert W. Genomic sequencing. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1984;81:1991–1995. doi: 10.1073/pnas.81.7.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dary A, Martin P, Wenner T, Decaris B, Leblond P. DNA rearrangements at the extremities of the Streptomyces ambofaciens linear chromosome: Evidence for developmental control. Biochimie. 2000;82:29–34. doi: 10.1016/s0300-9084(00)00348-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeRisi JL, Iyer VR, Brown PO. Exploring the metabolic and genetic control of gene expression on a genomic scale. Science. 1997;278:680–686. doi: 10.1126/science.278.5338.680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galas DJ, Schmitz A. DNase footprinting: A simple method for the detection of protein–DNA binding specificity. Nucleic Acids Res. 1978;5:3157–3170. doi: 10.1093/nar/5.9.3157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garvik B, Carson M, Hartwell L. Single-stranded DNA arising at telomeres in cdc13 mutants may constitute a specific signal for the RAD9 checkpoint. Mol Cell Biol. 1995;15:6128–6138. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.11.6128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorbunova V, Levy AA. Non-homologous DNA end joining in plant cells is associated with deletions and filler DNA insertions. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:4650–4657. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.22.4650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greider CW. Telomere length regulation. Annu Rev Biochem. 1996;65:337–365. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.65.070196.002005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harlow E, Lane D. Antibodies. A laboratory manual. Cold Spring Harbor, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Hay RT. Adenovirus DNA replication. In: DePamphilis ML, editor. DNA replication in eukaryotic cells. Cold Spring Harbor, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1996. pp. 699–719. [Google Scholar]

- Hirochika H, Sakaguchi K. Analysis of linear plasmids isolated from Streptomyces: Association of protein with the ends of the plasmid DNA. Plasmid. 1982;7:59–65. doi: 10.1016/0147-619x(82)90027-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirochika H, Nakamura K, Sakaguchi K. A linear DNA plasmid from Streptomyces rochei with inverted terminal repetition of 614 base pairs. EMBO J. 1984;3:761–766. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1984.tb01881.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hopwood DA, Kieser T, Wright HM, Bibb MJ. Plasmids, recombination and chromosome mapping in Streptomyces lividans 66. J Gen Microbiol. 1983;129:2257–2269. doi: 10.1099/00221287-129-7-2257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hopwood DA, Chater KF, Bibb MJ. Genetics of antibiotic production in Streptomyces coelicolor A3(2), a model streptomycete. Biotechnology. 1995;28:65–102. doi: 10.1016/b978-0-7506-9095-9.50009-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang C, Lin Y, Huang S, Chen CW. The telomeres of Streptomyces chromosomes contain conserved palindromic sequences with potential to form complex secondary structures. Mol Microbiol. 1998;28:905–916. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.00856.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang J, Lih CJ, Pan KH, Cohen SN. Global analysis of growth phase responsive gene expression and regulation of antibiotic biosynthetic pathways in Streptomyces coelicolor using DNA microarrays. Genes & Dev. 2001;15:3183–3192. doi: 10.1101/gad.943401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaiser C, Michaelis S, Mitchell A. Methods in yeast genetics, a Cold Spring Harbor laboratory course manual. Cold Spring Harbor, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Kieser T, Bibb MJ, Chater KF, Butter MJ, Hopwood DA. Practical Streptomyces genetics. Norwich, UK: John Innes Centre; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Kinashi H, Shimaji M, Sakai M. Giant linear plasmids in Streptomyces which code for antibiotic biosynthesis genes. Nature. 1987;328:454–456. doi: 10.1038/328454a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kornberg A, Baker TA. DNA replication. 2nd ed. New York: Freeman; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Kurosawa Y, Ogawa T, Hirose S, Okazaki T, Okazaki R. Mechanism of DNA chain growth. XV. RNA-linked nascent DNA pieces in Escherichia coli strains assayed with spleen exonuclease. J Mol Biol. 1975;96:653–664. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(75)90144-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leblond P, Decaris B. New insights into the genetic instability of Streptomyces. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1994;123:225–232. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1994.tb07229.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin Y, Chen CW. Instability of artificially circularized chromosomes of Streptomyces lividans. Mol Microbiol. 1997;26:709–719. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.5991975.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin Y, Kieser HM, Hopwood DA, Chen CW. The chromosome DNA of Streptomyces lividans 66 is linear. Mol Microbiol. 1993;10:923–933. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1993.tb00964.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lingner J, Cech TR. Telomerase and chromosome end maintenance. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 1998;8:226–232. doi: 10.1016/s0959-437x(98)80145-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McEachern MJ, Krauskopf A, Blackburn EH. Telomeres and their control. Annu Rev Genet. 2000;34:331–358. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genet.34.1.331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meijer WJ, Horcajadas JA, Salas M. φ29 family of phages. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2001;65:261–287. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.65.2.261-287.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore JK, Haber JE. Capture of retrotransposon DNA at the sites of chromosomal double-strand breaks. Nature. 1996;383:644–646. doi: 10.1038/383644a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Musialowski MS, Flett F, Scott GB, Hobbs G, Smith CP, Oliver SG. Functional evidence that the principal DNA replication origin of the Streptomyces coelicolor chromosome is close to the dnaA-gyrB region. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:5123–5125. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.16.5123-5125.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan KH, Lih CJ, Cohen SN. Analysis of DNA microarrays using algorithms that employ rule-based expert knowledge. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2002;99:2118–2123. doi: 10.1073/pnas.251687398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pennock E, Buckley K, Lundblad V. Cdc13 delivers separate complexes to the telomere for end protection and replication. Cell. 2001;104:387–396. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00226-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qin ZJ, Cohen SN. Replication at the Streptomyces linear plasmid pSLA2. Mol Microbiol. 1998;28:893–903. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.00838.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ————— Long palindromes formed in Streptomyces by nonrecombinational intra-strand annealing. Genes & Dev. 2000;14:1789–1796. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ————— Survival mechanisms for Streptomyces linear replicons after telomere damage. Mol Microbiol. 2002;45:785–794. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2002.03051.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Redenbach M, Flett F, Piendl W, Glocker I, Rauland U, Wafzig O, Kliem R, Leblond P, Cullum J. The Streptomyces lividans 66 chromosome contains a 1 MB deletogenic region flanked by two amplifiable regions. Mol Gen Genet. 1993;241:255–262. doi: 10.1007/BF00284676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Redenbach M, Kieser HM, Denapaite D, Eichner A, Cullum J, Kinashi H, Hopwood DA. A set of ordered cosmids and a detailed genetic and physical map for the 8 Mb Streptomyces coelicolor A3(2) chromosome. Mol Microbiol. 1996;21:77–96. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1996.6191336.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakaguchi K. Invertrons, a class of structurally and functionally related genetic elements that includes linear DNA plasmids, transposable elements and genomes of adeno-type viruses. Microbiol Rev. 1990;54:66–74. doi: 10.1128/mr.54.1.66-74.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salas M. Protein-priming of DNA replication. Annu Rev Biochem. 1991;60:39–71. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.60.070191.000351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sambrook J, Russell D. Molecular cloning: A laboratory manual. 3rd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Shiffman D, Cohen SN. Reconstruction of a Streptomyces linear replicon from separately cloned DNA fragments: Existence of a cryptic origin of circular replication within the linear plasmid. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1992;898:6129–6133. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.13.6129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sutton MD, Smith BT, Godoy VG, Walker GC. The SOS response: Recent insights into umuDC-dependent mutagenesis and DNA damage tolerance. Annu Rev Genet. 2000;34:479–497. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genet.34.1.479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Vliet PC. Adenovirus DNA replication. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 1995;199:1–30. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-79499-5_1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volff JN, Altenbucher J. Genetic instability of the Streptomyces chromosome. Mol Microbiol. 1998;27:239–246. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.00652.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ————— A new beginning with new ends: Linearisation of circular chromosomes during bacterial evolution. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2000;186:143–150. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2000.tb09095.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volff JN, Vandewiele D, Simonet JM, Decaris BJ. Stimulation of genetic instability in Streptomyces ambofaciens ATCC 23877 by antibiotics that interact with DNA gyrase. Gen Microbiol. 1993a;139:2551–2558. doi: 10.1099/00221287-139-11-2551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ————— Ultraviolet light, mitomycin C and nitrous acid induce genetic instability in Streptomyces ambofaciens ATCC23877. Mutat Res. 1993b;287:141–156. doi: 10.1016/0027-5107(93)90008-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volff JN, Viell P, Altenbuchner J. Artificial circularization of the chromosome with concomitant deletion of its terminal inverted repeats enhances genetic instability and genome rearrangement in Streptomyces lividans. Mol Gen Genet. 1997;253:753–760. doi: 10.1007/s004380050380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang SJ, Chang HM, Lin YS, Huang CH, Chen CW. Streptomyces genomes: Circular genetic maps from the linear chromosomes. Microbiology. 1999;145:2209–2220. doi: 10.1099/00221287-145-9-2209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson JD. Origin of concatemeric T7 DNA. Nat New Biol. 1972;239:197–201. doi: 10.1038/newbio239197a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang CC, Huang CH, Li CY, Tsay YG, Lee SC, Chen CW. The terminal proteins of linear Streptomyces chromosomes and plasmids: A novel class of replication priming proteins. Mol Microbiol. 2002;43:297–305. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang MC, Losick R. Cytological evidence for association of the ends of the linear chromosome in Streptomyces coelicolor. J Bacteriol. 2001;183:5180–5186. doi: 10.1128/JB.183.17.5180-5186.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoo SK, Ito J. Initiation of bacteriophage PRD1 DNA replication on single-stranded templates. J Mol Biol. 1991;222:127–131. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(91)90197-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu X, Gabriel A. Patching broken chromosomes with extranuclear cellular DNA. Mol Cell. 1999;4:873–881. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80397-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zakrzewska-Czerwinska J, Nardmann J, Schrempf H. Inducible transcription of the dnaA gene from Streptomyces lividans 66. Mol Gen Genet. 1994;242:440–447. doi: 10.1007/BF00281794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]