Abstract

Left-sided expression of Nodal in the lateral plate mesoderm is a conserved feature necessary for the establishment of normal left–right asymmetry during vertebrate embryogenesis. By using gain- and loss-of-function experiments in zebrafish and mouse, we show that the activity of the Notch pathway is necessary and sufficient for Nodal expression around the node, and for proper left–right determination. We identify Notch-responsive elements in the Nodal promoter, and unveil a direct relationship between Notch activity and Nodal expression around the node. Our findings provide evidence for a mechanism involving Notch activity that translates an initial symmetry-breaking event into asymmetric gene expression.

Keywords: Left–right asymmetry, Nodal, Notch signaling, Sonic hedgehog, Pitx2, zebrafish

Vertebrates display a left–right (LR) asymmetry that is most evident in the disposition of internal organs. In recent years, our understanding of the molecular mechanisms involved in LR determination during vertebrate embryogenesis has increased significantly. A genetic cascade has been proposed that positions and restricts the expression of Nodal on the left side of the lateral plate mesoderm (LPM; for reviews, see Burdine and Schier 2000; Capdevila et al. 2000; Mercola and Levin 2001; Hamada et al. 2002). This left-sided expression of Nodal is a conserved feature of all vertebrate embryos studied to date, and correlates with the normal establishment of LR asymmetry.

The expression pattern of Nodal during early embryo development is tightly regulated. Transgenic approaches in mice have identified node-specific enhancer (NDE) and left-side asymmetric enhancer (ASE) elements within the Nodal gene (Adachi et al. 1999; Norris and Robertson 1999). Recent evidence using conditional ablation of Nodal gene expression in the mouse have conclusively shown that Nodal expression around the node is critical for the establishment of asymmetric gene expression in the left LPM, including that of Nodal (Brennan et al. 2002; Saijoh et al. 2003). Here we identify binding sequences for the Notch pathway effector RBPjk/CBF1/Su(H) in the NDE of the Nodal promoter. We also show that Notch activity is necessary and sufficient to induce Nodal expression around the node. Notch activity appears, therefore, to function as a key regulator of proper LR determination, as well as one of the earliest genes upstream of Nodal expression identified to date.

Results and Discussion

The Notch pathway includes a transmembrane receptor (Notch), the DSL ligands (Delta and Serrate/Jagged in Drosophila and vertebrates, Lag-2 in Caenorhabditis elegans), and CSL DNA-binding protein (CBF1/RBPjk in vertebrates, Su(H) in Drosophila, Lag-1 in C. elegans; for review, see Artavanis-Tsakonas et al. 1999). Upon binding to the DSL ligands, the cytoplasmic domain of Notch is cleaved and released, enters the nucleus, and acts as a transcription factor in conjunction with the CSL DNA-binding proteins. Thus, an experimental strategy to activate the Notch pathway is to induce the expression of the intracellular domain of Notch (NotchIC). We injected one-cell stage zebrafish embryos with in vitro transcribed mRNA encoding mouse NotchIC, and evaluated its effects on LR establishment. To analyze the fate of the injected mRNA, we performed in situ hybridization with a mouse-specific NotchIC cRNA probe. Upon injection, patches of expression were distributed throughout the embryo (n = 150; Fig. 1B). To confirm that NotchIC effectively activates Notch signaling in zebrafish embryos, we analyzed the expression of hairy and enhancer of split 5 (hes5), an in vivo target of the Notch pathway (de la Pompa et al. 1997), and of deltaC, a zebrafish homolog of mouse Delta-like 1 (Dll1; Bettenhausen et al. 1995). For this purpose, we cloned a zebrafish homolog of hes5 (GenBank accession no. AY264404), and analyzed its expression and that of deltaC in control and NotchIC mRNA-injected embryos. A dramatic up-regulation of both transcripts was detected in embryos injected with NotchIC (Fig. 1C–F), indicating that this treatment results in effective domains of Notch activation throughout the embryo during gastrulation and somitogenesis. When embryos injected with NotchIC were allowed to develop further, we observed a wide array of developmental alterations affecting the anteroposterior and dorsoventral axes. Interestingly, the LR axis was also altered in 47% of embryos (n = 450) injected with NotchIC mRNA, as evaluated by reversal of heart looping. To confirm that the alterations in heart looping were not a consequence of other developmental alterations, we restricted our analyses to embryos not displaying evident alterations in the anteroposterior or dorsoventral axes. Also in this case the LR axis appeared randomized, with almost 50% of embryos (68 out of 142) displaying reversed heart looping (Fig. 1I,J).

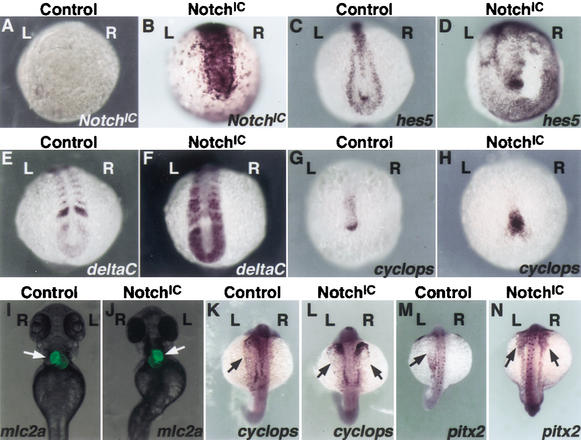

Figure 1.

Increased Notch activity alters left–right development. (A–H) NotchIC (A,B), hes5 (C,D), deltaC (E,F), and cyclops (G,H) transcripts in 12-hpf control (A,C,E,G), and NotchIC mRNA-injected (B,D,F,H) zebrafish embryos. Embryo views are posterior, dorsal to the top. (I,J) Transgenic zebrafrish embryos expressing a heart-specific mlc2a-EGFP reporter were injected with NotchIC mRNA (J). This treatment resulted in alterations in heart looping and positioning (arrow), when compared to control embryos (I). Embryo views are ventral, anterior to the top. (K–N) Whole-mount in situ hybridization for the Nodal-related gene cyclops (K,L) and pitx2 (M,N) revealed the appearance of ectopic transcripts for both genes in the right LPM of 24-hpf NotchIC-injected embryos (L,N, arrows). Embryo views are dorsal, anterior to the top. Left (L) and right (R) sides are indicated.

We then analyzed the expression of genes involved in LR asymmetry, including the Nodal-related gene cyclops and pitx2, normally expressed only in the left LPM. Injection of NotchIC mRNA resulted in bilateral expression of both genes in the LPM at 20 hpf (45% and 50%, n = 48 and 36 for cyclops and pitx2, respectively; Fig. 1K–N), indicating that Notch activity acts early in the genetic cascade determining LR asymmetry in zebrafish embryos. To investigate the mechanism by which Notch activation results in laterality defects, we analyzed cyclops expression at earlier developmental stages. In 11–12 hpf embryos, cyclops is expressed in two distinct domains, anterior and posterior, the latter associated to the embryonic shield (Fig. 1G; Rebagliati et al. 1998). This structure has been proposed to represent the zebrafish node (Essner et al. 2002, and references therein). NotchIC-injected embryos displayed strong up-regulation of cyclops expression around the node (98%, n = 320). Interestingly, this expression was not perfectly symmetric in most injected embryos (Fig. 1H), indicating that NotchIC injection induces LR defects by creating asymmetric domains of perinodal cyclops expression. These results further suggest that Notch activity is able to up-regulate cyclops expression around the node.

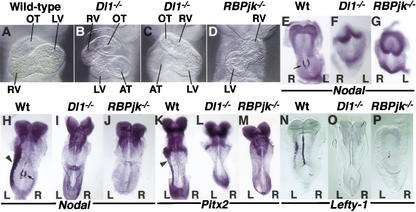

To verify the evolutionary conservation of the role of the Notch pathway in LR development, we undertook a series of loss-of-function analyses in the mouse, using the two targeted mutants of the Notch pathway that display the most severe developmental phenotypes; that of the ligand Dll1 (Hrabe de Angelis et al. 1997), and that of the effector RBPjk (Oka et al. 1995). After careful examination, we were able to detect reversed heart looping in around 60% of embryos homozygous for mutations in either Dll1 (Fig. 2B,C; n = 12), or RBPjk (Fig. 2D; n = 12). The analysis of laterality genes revealed that Nodal expression was absent from the node and the left LPM in either mutant of the Notch pathway (Fig. 2E–J; n = 7 and 9 for Dll1−/− and RBPjk−/−, respectively). These results indicate that Nodal expression around the node depends on Dll1-mediated Notch activity. The finding that Nodal expression around the node is necessary for Nodal expression in the LPM is in agreement with recent evidence from experiments with node-specific Nodal deletion (Brennan et al. 2002; Saijoh et al. 2003). Consistent with the absence of Nodal expression, we could not detect Pitx2 transcripts in the LPM of around 50% of Dll1−/− (Fig. 2L; n = 4) or RBPjk−/− (Fig. 2M; n = 8) mutants. Surprisingly, the remaining mutant embryos showed normal left-sided expression of Pitx2 in the LPM, except for one RBPjk−/− embryo, which displayed bilateral expression (data not shown). The fact that Pitx2 expression is uncorrelated to that of Nodal has been previously reported for a variety of experimental conditions, and is likely to reflect the existence of additional activator(s) of Pitx2 in the LPM (Constam and Robertson 2000; Pennekamp et al. 2002). We also analyzed the expression of Lefty-1, a gene also required for proper LR asymmetry (Meno et al. 1998), in Dll1−/− and RBPjk−/− embryos. No Lefty-1 expression could be detected in any of the mutant embryos analyzed (Fig. 2N–P; n = 3 each).

Figure 2.

Notch activity is necessary for Nodal expression and proper left–right determination. (A–D) Frontal views of E9.5 wild-type (A), Dll1−/− (B,C), and RBPjk−/− (D) embryos. Normal rightward heart looping is evident in wild-type embryos (A), while Dll1−/− and RBPjk−/− mutants display alterations in heart looping, ranging from incomplete looped heart (C), to leftward looping (B,D). OT, outflow tract; RV, right ventricle; LV, left ventricle; AT, atrium. (E–P) Whole-mount in situ hybridization for genes implicated in normal LR development revealed that Nodal transcripts were absent in the perinodal region of Dll1−/− and RBPjk−/− mice (E–G, arrow in E denotes presence in wild type) and also, later on, were absent in the left LPM (H–J). Pitx2 transcripts were also absent from the left LPM (K–M; arrowhead in H and K denotes presence in wild type). Similarly, the midline and LPM domains of expression of Lefty1 were absent in both Dll1−/− and RBPjk−/− mice (N–P). Embryo views are ventral, anterior to the top in E–G, and dorsal, anterior to the top in H–P. Please note that coloring reaction for in situ hybridizations was allowed to proceed longer than usual to verify the absence of signal in the mutants; hence, the increased background. Left (L) and right (R) sides are indicated.

These results, together with our gain-of-function experiments in zebrafish, indicate that Notch activity is both necessary and sufficient for Nodal expression around the node. During the preparation of this manuscript, evidence was published showing that Dll1 mutants display a variety of LR defects (Przemeck et al. 2003). In this report, however, Nodal expression was found to be randomized, 14% of the embryos showing bilateral expression in the LPM. The authors also report alterations in the node and midline of Dll1−/− embryos, proposed to cause the LR defects observed in these mutants. These findings differ both from ours and from those reported by Krebs et al. (2003), for reasons that are unclear to us. The genetic background in which the mutations are maintained could account for the different results obtained. While the Dll1−/− and RBPjk−/− lines used in our studies are backcrossed into an outbred ICR background, those used by Przemeck et al. (2003) are kept on a mixed 129Sv;C57BL/6J background. Independently of the cause for such apparently conflicting results, our analysis of two different mouse mutants with loss of Notch function (see also Krebs et al. 2003), as well as gain-of-function experiments in zebrafish, has allowed us to unveil a relationship between Notch activity and Nodal expression.

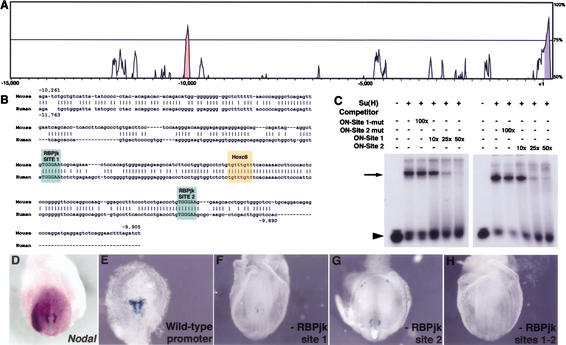

Studies were performed in silico, in vitro, and in vivo to further investigate the nature of the genetic relationship between Notch activity and Nodal expression. A search for conserved regions in the noncoding sequences of the human and mouse Nodal genes revealed the existence of one region of high (>75%) conservation centered at −10 kb (Fig. 3A). This evolutionarily conserved region lies within the previously characterized Nodal NDE (Adachi et al. 1999; Norris and Robertson 1999; Brennan et al. 2002). A search for conserved regulatory elements in this region identified a consensus binding-site for Hoxc8 and two binding-sites for CBF1/RBPjk (Fig. 2B). To ascertain whether these putative binding sites are able to bind RBPjk, we performed electrophoretic mobility shift assays using a DNA probe representing nucleotides −10,261 to −9,905 in the mouse Nodal gene, and recombinant Su(H) produced in bacteria. The transcription factor efficiently bound to the Nodal promoter in vitro, as assessed by a shift in the probe's mobility. This binding could be competed with synthetic oligonucleotides representing either putative RBPjk-binding site and flanking regions, but not with oligonucleotides in which the putative recognition sites had been mutated (Fig. 2C). These results suggest that perinodal expression of Nodal may be regulated by conserved promoter elements that depend directly on Notch activity.

Figure 3.

Nodal is a direct target of the Notch pathway. (A) Sequences representing 15 kb of genomic DNA 5′ of the starting codon of human and mouse Nodal were aligned using the AVID algorithm and the output generated by the VISTA set (http://www.gsd.lbl.gov/vista/index.html). Exon 1 is labeled in magenta. Only one noncoding region (pale red) shows more than 75% homology between human and mouse DNA sequences. The sequence of a 355-bp BglII fragment of the mouse gene containing the evolutionarily conserved region is shown in B. Gaps introduced by the alignment algorithm are indicated by dashes. Some regions in the human sequence not aligning with mouse Nodal have been removed for clarity, and are indicated by spaces. Colored boxes mark the putative transcription factor binding sites identified using MatInspector with TRANSFAC 4.0 matrices (http://transfac.gbf.de/TRANSFAC). (C) A 32P-labeled probe representing the mouse Nodal sequence depicted in B was incubated in the absence (lanes 1,7) or in the presence (lanes 2–6,8–12) of purified recombinant Su(H), and the indicated competitors. Oligonucleotides (20-mer) representing the putative RBPjk binding sites 1 (ON-Site 1) and 2 (ON-Site 2), and their respective flanking regions, or equivalent oligonucleotides where the putative binding site was mutated (ON-Site 1-mut and ON-Site 2-mut), were used to compete the binding at the indicated molar excess (×). The arrow indicates the change in the probe's mobility caused by binding to Su(H). The arrowhead points to the free probe. (D–H) A genomic DNA fragment representing the sequences shown in B was used to drive the expression of lacZ in transgenic mouse embryos. β-Galactosidase staining of E7.5–E8.0 embryos (E) recapitulates the endogenous Nodal expression around the node (D). Transgenes in which the putative RBPjk binding site 1 (F) or 2 (G) are mutated to a PmeI recognition site drive weak ectopic expression of lacZ. (H) When both sites are mutated, no lacZ expression could be detected.

To investigate whether these elements are functional in vivo, we utilized a transgenic approach in mice. A 355-bp fragment of the mouse Nodal promoter containing the RBPjk-binding sites was fused to a lacZ-reporter cassette to create a transgene similar to others previously shown to drive expression around the node (Adachi et al. 1999; Norris and Robertson 1999; Brennan et al. 2002). We also generated mutant versions of this construct in which the first, second, or both RBPjk-binding sites were substituted for an unrelated sequence, recognized by the endonuclease Pme I. Six β-galactosidase-positive embryos were obtained for the wild-type reporter construct, from a total of 10 showing transgene integration by PCR. The staining pattern in those embryos was very similar, limited to the perinodal region, recapitulating the endogenous Nodal expression around the node (Fig. 3D,E), consistent with previous results utilizing comparable transgenes (Adachi et al. 1999; Norris and Robertson 1999). For the 5′ RBPjk-binding site mutation, no node-specific lacZ expression was detected in eight embryos that were positive for transgene integration by PCR (Fig. 3F). A weak, ectopic β-galactosidase staining was observed in one transgenic embryo out of seven obtained after injection of the construct mutated at the 3′ RBPjk-binding site (Fig. 3G). The combined mutation resulted in a complete absence of lacZ expression in 15 embryos that showed transgene integration (Fig. 3H). Taken together, our results show that there are two conserved RBPjk recognition sites in the Nodal promoter, and that both sites are required for perinodal expression of Nodal in the mouse embryo.

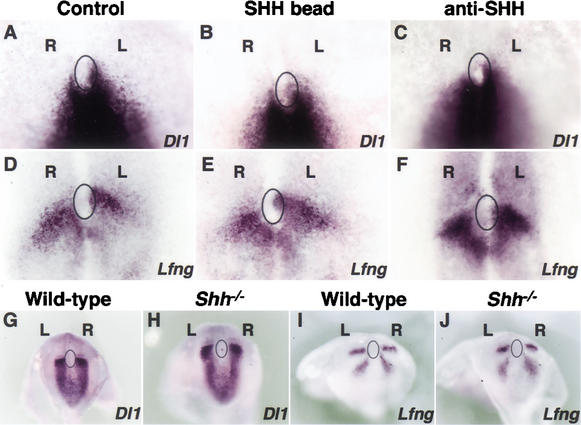

One of the earliest determinants of LR establishment in the chick embryo is the left-sided expression of Shh around Hensen's node. At Hamburger-Hamilton stage 5 (HH; Hamburger and Hamilton 1951), Shh transcripts become asymmetrically localized on the anterior-left side of the node. Gain- and loss-of-function studies indicate that this asymmetric expression is pivotal for the subsequent left-sided Nodal expression in the LPM (Pagan-Westphal and Tabin 1998). Because our results show that Notch activity is immediately upstream of Nodal expression in the node, we reasoned that SHH might regulate Nodal expression by modulating Notch activity. To address this possibility, we monitored Notch activity by analyzing the expression pattern of Dll1 [up-regulated by Notch activation in zebrafish (Fig. 1E,F) and chick embryos (data not shown)] after overexpression or down-regulation of SHH. We also analyzed the expression of Hes5 and Lunatic fringe (Lfng), both of which are regulated by Notch activity during somitogenesis (Barrantes et al. 1999; Morales et al. 2002), as well as during gastrulation (see below). Implantation on the right side of HH3–HH4 chick embryos of SHH-soaked beads did not perturb the normal expression of Dll1 (Fig. 4A,B; 90% of the implanted embryos, n = 10), Lfng (Fig. 4D,E; 90%, n = 10), or Hes5 (100%, n = 10; data not shown). Conversely, implantation of beads soaked in anti-SHH blocking antibody on the left side of HH3–HH4 chick embryos did not have any effect on Dll1 (Fig. 4A,C; 100%, n = 10), Lfng (Fig. 4D,F; 100%, n = 10), or Hes5 (100%, n = 10; data not shown) expression. We also analyzed the expression patterns of Dll1 and Lfng in mouse embryos homozygous for a Shh null mutation (Chiang et al. 1996). As with the chick experiments, the loss of Shh function did not induce alterations in the expression of either gene (Fig. 4G–J; data not shown; 100%, n = 5 each).

Figure 4.

Notch activity during left–right determination does not depend on SHH activity. Implantation on the right side of HH3–HH4 chick embryos of SHH soaked beads (B), or of anti-SHH blocking antibody on the left side (C) did not have any effect on Dll1 expression around Hensen's node. Similarly, Lfng transcripts were not altered after implanting SHH soaked beads (E) or anti-SHH antibody (F). (G–J) Whole-mount in situ hybridization in E7.5–E8.0 Shh−/− mouse embryos did not reveal any alteration in the expression pattern of either Dll1 or Lfng. Left (L) and right (R) sides are indicated. Relative position of the node is denoted by a circle.

These results indicate that Shh function does not regulate Notch activity around the node. Several lines of evidence indicate that monociliated cells in the mouse node function to provide asymmetric cues upstream of the Shh pathway. Notch activity, in turn, does not appear to regulate the normal function of nodal cilia (Krebs et al. 2003). Therefore, we tested whether Notch activity around the node is regulated by nodal flow. For this purpose, we analyzed the expression of components of the Notch pathway in several mouse mutants with disrupted nodal cilia function. We used the expression of Dll1 as a reporter of Notch activity, based on our finding that NotchIC injection up-regulates Delta-like genes during early development of zebrafish (Fig. 1E,F) and chick (data not shown) embryos. Additionally, we used the expression of Lfng, because its expression is dependent on Notch activity during mouse gastrulation, as indicated by the Lfng down-regulation observed in either Dll1 or RBPjk mutant mice (Fig. 5A–C).

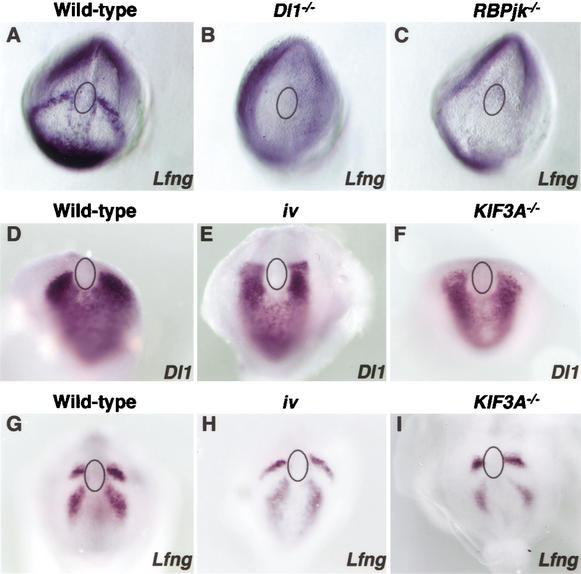

Figure 5.

Notch activity regulates left–right asymmetry independently of nodal cilia function. Lfng is expressed in E7.5–E8.0 control mouse embryos as two sharp bilateral perinodal stripes (A), barely observable in Dll1−/− (B) or RBPjk−/− (C) embryos, indicating that Lfng expression depends of Notch activity during mouse gastrulation. Analysis of Dll1 expression in E7.5–E8.0 iv (E) and KIF3A−/− (F) embryos did not reveal any alteration in the expression pattern when compared to control littermates (D). Similarly, Lfng expression is not altered in iv (H) or KIF3A−/− (I) embryos, when compared to that of wild-type (G). Relative position of the node is denoted by a circle.

The mouse mutation inversus viscerum (iv), characterized by randomization in LR asymmetry, disrupts the gene encoding the ciliary motor “left–right” dynein (Supp et al. 1997), and results in immotile nodal cilia (Okada et al. 1999). Nodal expression in the LPM of iv mutants is randomized (Lowe et al. 1996). We analyzed the expression of Dll1 and Lfng in E7.5–E8.0 mouse embryos homozygous for the iv mutation, and found no obvious differences in their expression pattern when compared to wild-type littermates (Fig. 5D–E,G–H; 100%, n = 8 each). To confirm these results, we repeated our analyses in a different model of nodal cilia dysfunction. Embryos mutant for the microtubule-associated motor protein kinesin KIF3A display randomization of LR determination and alterations in nodal flow (Marszalek et al. 1999; Takeda et al. 1999). Again, we were unable to detect any alteration in the expression of either Dll1 (Fig. 5D,F; 100%, n = 7) or Lfng (Fig. 5G,I; 100%, n = 6) in KIF3A−/− embryos. The results obtained from the analyses in both mouse mutations suggest that the mechanism by which the Notch pathway regulates LR determination does not depend on the proper function of nodal cilia.

We provide evidence for an evolutionarily conserved role of Notch signaling in the establishment of the LR axis in fish and mammals. Our results also demonstrate an absolute requirement of Notch signaling for Nodal expression around the node, and the need for perinodal expression of Nodal for its subsequent activation in the LPM (see also Brennan et al. 2002; Saijoh et al. 2003). Although it remains to be determined whether different species utilize a common mechanism to break the initial LR symmetry, a conserved feature of early normal LR determination is the left-sided expression of Nodal in the LPM. Our results unveil the existence of an earlier conserved feature, represented by the Notch signaling pathway, whose activity lies directly upstream of Nodal expression around the node, and whose normal function is critical for correct LR specification.

Materials and methods

Chick embryo culture and bead implantation

Chick embryos were explanted and grown in vitro as described (Izpisua-Belmonte et al. 1993). Beads were soaked in SHH protein or anti-SHH antibody as described (Rodriguez-Esteban et al. 1999).

Zebrafish embryo manipulation

Zebrafish embryo maintenance, culture, and RNA injection were as described (Ng et al. 2002).

In situ hybridization

After the different treatments, we processed embryos for whole-mount in situ hybridization as previously published (Izpisua-Belmonte et al. 1993; Ng et al. 2002). The different cDNAs utilized for the antisense probes utilized for mouse, chick, and zebrafish in situ hybridization have been described elsewhere. Details will be provided upon request.

Mutant and transgenic mice

A BglII fragment of the mouse Nodal promoter comprising nucleotides −10,261 to −9,905, and mutated versions thereof, were fused to an hsp68 minimal promoter and the coding sequences of lacZ. Linearized DNA was injected into the male pronucleus of B6D2F1 fertilized oocytes. After transferring to pseudo-pregnant ICR females, embryos were recovered at E7.5–E8.5 and stained for β-galactosidase activity following standard procedures. Presence of the transgene was confirmed by PCR of yolk sac genomic DNA using primers specific for lacZ. RBPjk−/−, Shh−/−, iv, Dll1−/−, and KIF3A−/− mice have been previously reported (Oka et al. 1995; Chiang et al. 1996; Lowe et al. 1996; Hrabe de Angelis et al. 1997; Marszalek et al. 1999). Genotyping was performed following the original descriptions.

Acknowledgments

We thank May Schwarz, Harley Pineda, and Reiko Aoki for their excellent technical assistance; Dr. Gabriel Sternik for his time and expertise with microscopy; and Lorraine Hooks for help in preparing the manuscript. We are indebted to Dr. Chris Kintner for his generosity in sharing various reagents and insightful comments on the Notch pathway, and to Drs. Tom Gridley and Hiroshi Hamada for communicating unpublished results. We are most grateful to Drs. Phil Beachy, Larry Goldstein, and Paul Overbeek for generously sharing mouse mutants. A.R. is partially supported by a postdoctoral fellowship from the Ministerio de Educación, Cultura y Deporte, Spain; C.M.K. is partially supported by a postdoctoral fellowship from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research; and T.I. is supported by a JSPS Postdoctoral Fellowships for Research Abroad, Japan. This work was supported by grants from the March of Dimes, the G. Harold and Leila Y. Mathers Charitable Foundation, BioCell, and the NIH to JCIB.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by payment of page charges. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

Footnotes

E-MAIL belmonte@salk.edu; FAX (858) 453-2573.

Article published online ahead of print. Article and publication date are at http://www.genesdev.org/cgi/doi/10.1101/gad.1084403.

References

- Adachi H, Saijoh Y, Mochida K, Ohishi S, Hashiguchi H, Hirao A, Hamada H. Determination of left/right asymmetric expression of nodal by a left side-specific enhancer with sequence similarity to a lefty-2 enhancer. Genes & Dev. 1999;13:1589–1600. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.12.1589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Artavanis-Tsakonas S, Rand MD, Lake RJ. Notch signaling: Cell fate control and signal integration in development. Science. 1999;284:770–776. doi: 10.1126/science.284.5415.770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrantes IB, Elia AJ, Wunsch K, De Angelis MH, Mak TW, Rossant J, Conlon RA, Gossler A, de la Pompa JL. Interaction between Notch signalling and Lunatic fringe during somite boundary formation in the mouse. Curr Biol. 1999;9:470–480. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(99)80212-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bettenhausen B, Hrabe de Angelis M, Simon D, Guenet JL, Gossler A. Transient and restricted expression during mouse embryogenesis of Dll1, a murine gene closely related to Drosophila Delta. Development. 1995;121:2407–2418. doi: 10.1242/dev.121.8.2407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brennan J, Norris DP, Robertson EJ. Nodal activity in the node governs left–right asymmetry. Genes & Dev. 2002;16:2339–2344. doi: 10.1101/gad.1016202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burdine RD, Schier AF. Conserved and divergent mechanisms in left–right axis formation. Genes & Dev. 2000;14:763–776. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capdevila J, Vogan KJ, Tabin CJ, Izpisua Belmonte JC. Mechanisms of left–right determination in vertebrates. Cell. 2000;101:9–21. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)80619-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiang C, Litingtung Y, Lee E, Young KE, Corden JL, Westphal H, Beachy PA. Cyclopia and defective axial patterning in mice lacking Sonic hedgehog gene function. Nature. 1996;383:407–413. doi: 10.1038/383407a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Constam DB, Robertson EJ. Tissue-specific requirements for the proprotein convertase furin/SPC1 during embryonic turning and heart looping. Development. 2000;127:245–254. doi: 10.1242/dev.127.2.245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de la Pompa JL, Wakeham A, Correia KM, Samper E, Brown S, Aguilera RJ, Nakano T, Honjo T, Mak TW, Rossant J, et al. Conservation of the Notch signalling pathway in mammalian neurogenesis. Development. 1997;124:1139–1148. doi: 10.1242/dev.124.6.1139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Essner JJ, Vogan KJ, Wagner MK, Tabin CJ, Yost HJ, Brueckner M. Conserved function for embryonic nodal cilia. Nature. 2002;418:37–38. doi: 10.1038/418037a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamada H, Meno C, Watanabe D, Saijoh Y. Establishment of vertebrate left–right asymmetry. Nat Rev Genet. 2002;3:103–113. doi: 10.1038/nrg732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamburger V, Hamilton HL. A series of normal stages in the development of the chick embryo. J Morphol. 1951;88:49–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hrabe de Angelis M, McIntyre J, II, Gossler A. Maintenance of somite borders in mice requires the Delta homologue DII1. Nature. 1997;386:717–721. doi: 10.1038/386717a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Izpisua-Belmonte JC, De Robertis EM, Storey KG, Stern CD. The homeobox gene goosecoid and the origin of organizer cells in the early chick blastoderm. Cell. 1993;74:645–659. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90512-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krebs, L.T., Iwai, N., Nonaka, S., Welsh, I.C., Lan, Y., Jiang, R., Saijoh, Y., O'Brien, T.P., Hamada, H., and Gridley, T. 2003. Notch signaling regulates left–right asymmetry determination by inducing Nodal expression. Genes & Dev. (this issue). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Lowe LA, Supp DM, Sampath K, Yokoyama T, Wright CV, Potter SS, Overbeek P, Kuehn MR. Conserved left–right asymmetry of nodal expression and alterations in murine situs inversus. Nature. 1996;381:158–161. doi: 10.1038/381158a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marszalek JR, Ruiz-Lozano P, Roberts E, Chien KR, Goldstein LS. Situs inversus and embryonic ciliary morphogenesis defects in mouse mutants lacking the KIF3A subunit of kinesin-II. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1999;96:5043–5048. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.9.5043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meno C, Shimono A, Saijoh Y, Yashiro K, Mochida K, Ohishi S, Noji S, Kondoh H, Hamada H. lefty-1 is required for left–right determination as a regulator of lefty-2 and nodal. Cell. 1998;94:287–297. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81472-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mercola M, Levin M. Left–right asymmetry determination in vertebrates. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2001;17:779–805. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.17.1.779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morales AV, Yasuda Y, Ish-Horowicz D. Periodic Lunatic fringe expression is controlled during segmentation by a cyclic transcriptional enhancer responsive to notch signaling. Dev Cell. 2002;3:63–74. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(02)00211-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ng JK, Kawakami Y, Buscher D, Raya A, Itoh T, Koth CM, Rodriguez Esteban C, Rodriguez-Leon J, Garrity DM, Fishman MC, et al. The limb identity gene Tbx5 promotes limb initiation by interacting with Wnt2b and Fgf10. Development. 2002;129:5161–5170. doi: 10.1242/dev.129.22.5161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norris DP, Robertson EJ. Asymmetric and node-specific nodal expression patterns are controlled by two distinct cis-acting regulatory elements. Genes & Dev. 1999;13:1575–1588. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.12.1575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oka C, Nakano T, Wakeham A, de la Pompa JL, Mori C, Sakai T, Okazaki S, Kawaichi M, Shiota K, Mak TW, et al. Disruption of the mouse RBP-J kappa gene results in early embryonic death. Development. 1995;121:3291–3301. doi: 10.1242/dev.121.10.3291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okada Y, Nonaka S, Tanaka Y, Saijoh Y, Hamada H, Hirokawa N. Abnormal nodal flow precedes situs inversus in iv and inv mice. Mol Cell. 1999;4:459–468. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80197-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pagan-Westphal SM, Tabin CJ. The transfer of left–right positional information during chick embryogenesis. Cell. 1998;93:25–35. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81143-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pennekamp P, Karcher C, Fischer A, Schweickert A, Skryabin B, Horst J, Blum M, Dworniczak B. The ion channel polycystin-2 is required for left–right axis determination in mice. Curr Biol. 2002;12:938–943. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(02)00869-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Przemeck GK, Heinzmann U, Beckers J, Hrabe de Angelis M. Node and midline defects are associated with left–right development in Delta1 mutant embryos. Development. 2003;130:3–13. doi: 10.1242/dev.00176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rebagliati MR, Toyama R, Fricke C, Haffter P, Dawid IB. Zebrafish nodal-related genes are implicated in axial patterning and establishing left–right asymmetry. Dev Biol. 1998;199:261–272. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1998.8935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez-Esteban C, Capdevila J, Economides AN, Pascual J, Ortiz A, Izpisua Belmonte JC. The novel Cer-like protein Caronte mediates the establishment of embryonic left–right asymmetry. Nature. 1999;401:243–251. doi: 10.1038/45738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saijoh Y, Oki S, Ohishi S, Hamada H. Left–right patterning of the mouse lateral plate requires Nodal produced in the node. Dev Biol. 2003;256:161–173. doi: 10.1016/s0012-1606(02)00121-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Supp DM, Witte DP, Potter SS, Brueckner M. Mutation of an axonemal dynein affects left–right asymmetry in inversus viscerum mice. Nature. 1997;389:963–966. doi: 10.1038/40140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takeda S, Yonekawa Y, Tanaka Y, Okada Y, Nonaka S, Hirokawa N. Left–right asymmetry and kinesin superfamily protein KIF3A: New insights in determination of laterality and mesoderm induction by kif3A−/− mice analysis. J Cell Biol. 1999;145:825–836. doi: 10.1083/jcb.145.4.825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]