Abstract

The mPer1, mPer2, mCry1, and mCry2 genes play a central role in the molecular mechanism driving the central pacemaker of the mammalian circadian clock, located in the suprachiasmatic nuclei (SCN) of the hypothalamus. In vitro studies suggest a close interaction of all mPER and mCRY proteins. We investigated mPER and mCRY interactions in vivo by generating different combinations of mPer/mCry double-mutant mice. We previously showed that mCry2 acts as a nonallelic suppressor of mPer2 in the core clock mechanism. Here, we focus on the circadian phenotypes of mPer1/mCry double-mutant animals and find a decay of the clock with age in mPer1-/- mCry2-/- mice at the behavioral and the molecular levels. Our findings indicate that complexes consisting of different combinations of mPER and mCRY proteins are not redundant in vivo and have different potentials in transcriptional regulation in the system of autoregulatory feedback loops driving the circadian clock.

Keywords: Circadian clock, Per, Cry, aging, transcription

The earth's rotation around the Sun has strongly influenced temporal organization of the mammalian organism manifested by near-24-h rhythms of biological processes (Pittendrigh 1993), including the sleep–wake cycle, energy metabolism, body temperature, renal activity, and blood pressure. These rhythms are maintained even in the absence of external time signals (Zeitgeber). They are driven by a central clock located in the suprachiasmatic nuclei (SCN) of the ventral hypothalamus (Rusak and Zucker 1979; Ralph et al. 1990). Because the internal period length generated by this pacemaker is not exactly 24 h, the clock has to be reset every day by an input pathway synchronizing the organism's biological processes with geophysical time. The daily variation in light intensity is monitored by photoreceptors in the eye that project into the SCN via the retinohypothalamic tract (RHT; Rusak and Zucker 1979) and the intergeniculate leaflet (IGL; Jacob et al. 1999). The oscillations generated in the SCN are translated into overt rhythms in behavior and physiology through output pathways that probably involve both chemical and electrical signals.

At the molecular level, circadian rhythms are generated by the integration of autoregulatory transcriptional/translational feedback loops (TTLs; Allada et al. 2001; Albrecht 2002; Reppert and Weaver 2002). In the mammalian system, the TTL can be subdivided into a positive and a negative limb. The positive limb is constituted by the PAS helix–loop–helix transcription factors CLOCK and BMAL1 that upon heterodimerization bind to “E-box” enhancer elements regulating transcription of Period (mPer) and probably also Cryptochrome (mCry) genes. The mPER and mCRY proteins are components of the negative limb that attenuate the CLOCK/BMAL1-mediated activation of their own genes and hence generate a negative feedback. A number of posttranslational events such as phosphorylation, ubiquitylation, degradation, and intracellular transport seem to be critical for the generation of oscillations in clock gene products and the stabilization of a 24-h period (Kume et al. 1999; Yagita et al. 2000, 2002; Lee et al. 2001; Miyazaki et al. 2001; Vielhaber et al. 2001; Yu et al. 2002). Additionally, the two limbs of the TTL are linked by the nuclear orphan receptor REV-ERBα, which is under the influence of mPer and mCry genes and controls transcription of Bmal1 (Preitner et al. 2002). In mammals, three Per genes—mPer1 (Sun et al. 1997; Tei et al. 1997), mPer2 (Albrecht et al. 1997; Shearman et al. 1997), and mPer3 (Zylka et al. 1998)—and two Cry genes—mCry1 and mCry2 (Miyamoto and Sancar 1998)—have been identified. Although mPer3 seems not to be necessary for the generation of circadian rhythmicity (Shearman et al. 2000), mPer1, mPer2, and both mCry genes have been demonstrated to play essential roles in the central oscillator as well as in the light-driven input pathway to the clock (van der Horst et al. 1999; Vitaterna et al. 1999; Zheng et al. 1999, 2001; Albrecht et al. 2001; Bae et al. 2001; Cermakian et al. 2001). In addition to the master clock in the SCN, most cells of peripheral tissues possess a circadian oscillator with a molecular organization very similar to that of SCN neurons, but lacking light-responsiveness (Balsalobre et al. 1998; Yamazaki et al. 2000; Yagita et al. 2001).

The molecular mechanism of clock autoregulation has largely been studied in vitro (Gekakis et al. 1998; Kume et al. 1999; Miyazaki et al. 2001; Vielhaber et al. 2001; Yagita et al. 2000, 2002; Yu et al. 2002). These studies point to multiple physical interactions between all mPER and mCRY proteins. However, the time course of protein availability, modification, and localization is difficult to resolve in cell and slice cultures (Jagota et al. 2000; Hamada et al. 2001; Lee et al. 2001). To elucidate the functional relationship between the mPer and mCry genes in vivo, we started to inactivate different combinations of mPer and mCry genes in mice (Oster et al. 2002).

Here we show that mPer1-/- mCry1-/- mice maintain a functional circadian clock and that mPer1-/- mCry2-/- mice lose circadian rhythmic behavior after a few months. This loss of rhythmicity is accompanied by altered regulation of expression of core clock components and the clock output gene arginine vasopressin (AVP). Our results indicate that the amount of mPER and mCRY proteins and hence the composition of mPER/mCRY complexes are critical for generation and maintenance of circadian rhythms.

Results

Generation of mPer1-/- mCry1-/- and mPer1-/- mCry2-/- mice

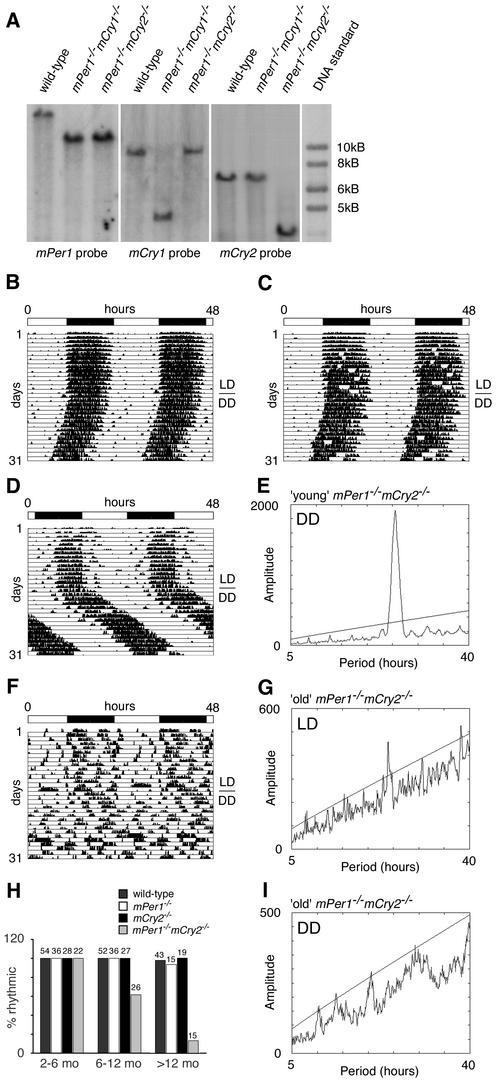

To begin to understand the in vivo function of the mPer and mCry genes in the clock mechanism, we generated mice with disruptions in both the mPer1/mCry1 or mPer1/mCry2 genes. Mice with a deletion of the mPer1 gene (Zheng et al. 2001) were crossed with mCry1-/- or mCry2-/- mice, respectively (van der Horst et al. 1999). The double-heterozygous offspring were intercrossed to produce wild-type and homozygous mutant animals. mPer1-/- mCry1-/- and mPer1-/- mCry2-/- mice (representative genotyping shown in Fig. 1A) were obtained at the expected Mendelian ratios and were morphologically indistinguishable from wild-type animals. The animals appeared normal in fertility, although in mPer1/mCry double-mutant mice, the intervals between two litters seem to increase significantly with progressing age (data not shown).

Figure 1.

Generation of mPer1mCry double-mutant mice and representative locomotor activity records. (A) Southern blot analysis of wild-type, mPer1-/- mCry1-/-, and mPer1-/- mCry2-/- tail DNA. The mPer1 probe hybridizes to a 20-kb wild-type and a 11.8-kb mutant fragment of EcoRI-digested genomic DNA. The mCry1 probe detects a 9-kb wild-type and a 4-kb NcoI-digested fragment of the targeted locus. In mCry2 mutants, the wild-type allele is detected by hybridization of the probe to a 7-kb EcoRI fragment, whereas the mutant allele yields a 3.5-kb fragment. (B–D,F) Representative locomotor activity records of wild-type (B), mPer1-/- mCry1-/- (C), young mPer1-/- mCry2-/- (D), and old mPer1-/- mCry2-/- (F) animals kept in a 12-h light/12-h dark (LD) cycle and in constant darkness (DD; transition indicated by the horizontal line). Activity is represented by black bars and is double-plotted with the activity of the following light/dark cycle plotted to the right and below the previous light/dark cycle. The top bar indicates light and dark phases in LD. For the first 5 d in DD, wheel rotations per day were 20,000 ± 2500 (n = 17) for wild-type animals, 21,500 ± 7300 (n = 15) for mPer1-/- mCry1-/- mutants, 25,100 ± 6200 (n = 14) for young mPer1-/- mCry2-/- mutants, and 17,200 + 7900 (n = 9) for old mPer1-/- mCry2-/- mutants. (E,G,I) Periodogram analysis of young mPer1-/- mCry2-/- animals in DD (E corresponds to activity plot in D), and old mPer1-/- mCry2-/- animals in LD (G corresponds to activity plot in F) and DD (I corresponds to activity plot in F). Analysis was performed on 10 consecutive days in LD or DD after animals were allowed to adapt 5 d to the new light regimen. The ascending straight line in the periodograms represents a statistical significance of p < 0.001 as determined by the ClockLab program. (H) Age dependence of rhythmicity in wild-type (dark gray bar), mPer1-/- (white bar), mCry2-/- (black bar), and mPer1-/- mCry2-/- (light gray bar) mice. The animals tested were divided into three groups according to their age (2–6 mo, 6–12mo, and >12 mo old). Rhythmicity in DD was determined by periodogram analysis. The values on top of each bar indicate the total numbers of animals tested per group and genotype.

mPer1 acts as a nonallelic suppressor of mCry1

To determine the influence of inactivation of the mCry1 gene on circadian behavior of mPer1-/- mice, mutant and wild-type animals were individually housed in circadian activity-monitoring chambers (Albrecht and Oster 2001; Albrecht and Foster 2002) for analysis of wheel-running activity. Mice were kept in a 12-h light/12-h dark cycle (LD 12:12, or LD) for several days to establish entrainment, and were subsequently kept in constant darkness (DD). Under LD and DD conditions, mPer1-/- mCry1-/- animals displayed activity and clock gene expression patterns similar to that of wild-type mice (Fig. 1B,C; Supplementary Fig. 1). Under DD conditions, mPer1-/- mCry1-/- mutant mice displayed a period length (τ) of 23.7 ± 0.2 h (mean ± S.D., n = 15), which is similar to that of wild-type animals (τ = 23.8 ± 0.1 h; n = 17). Thus, an additional deletion of mPer1 rescues the short-period phenotype of mCry1-deficient mice (van der Horst et al. 1999), indicating that mPer1 acts as a nonallelic suppressor of mCry1.

Loss of circadian wheel running activity rhythms in aging mPer1-/- mCry2-/- double-mutant mice

Analysis of circadian behavior of mPer1-/- mCry2-/- animals under LD conditions revealed that in young mPer1-/- mCry2-/- animals (between 2 and 6 mo old), the onset of activity was delayed as compared with wild-type animals and the highest activity could be observed in the second half of the night, with masking of activity during the first hours of the day (Fig. 1D). Under DD conditions, these animals display rhythmic behavior with a long period (τ) of 25.3 ± 0.2 h (mean ± S.D., n = 14) compared with wild-type animals (τ = 23.8 ± 0.1 h; n = 17; Fig. 1D,E).

Interestingly, mPer1-/- mCry2-/- animals that were >6 mo old displayed a markedly disturbed diurnal activity pattern under LD conditions (Fig. 1F), as evident from the very faint 24-h rhythm detected by χ2 periodogram analysis (Fig. 1G). Under DD conditions, old mPer1-/- mCry2-/- mice were completely arrhythmic (Fig. 1F,I), which sharply contrasts the robust rhythmicity of young mPer1-/- mCry2-/- mice under similar conditions. The transition from a rhythmic to an arrhythmic phenotype in mPer1-/- mCry2-/- mice correlated well with age (Fig. 1H). Whereas all mPer1-/- mCry2-/- mice at an age between 2 and 6 mo display circadian activity patterns, 40% of animals between 6 and 12 mo of age have lost circadian rhythmicity. When animals reached the age of 1 yr or older, even 87% of the mPer1-/- mCry2-/- mice have become arrhythmic. We did not observe a comparable age-related loss of rhythmicity in wild-type, mPer1-/- and mCry2-/- mice (Fig. 1 H; Supplementary Fig. 2A–C) and not in mPer1-/- mCry1-/-, mPer2Brdm1 mCry1-/- and mPer2Brdm1 mCry2-/- mice, respectively (Supplementary Fig. 2D).

Alterations in expression levels of clock components and the clock output gene Avp in aging mPer1-/- mCry2-/- double-mutant mice

To extend our observations to the molecular level, we examined the expression patterns of the mPer2, mCry1, and Bmal1 genes in 6–12-month-old mPer1-/- mCry2-/- mice under LD and DD conditions. For simplicity, we will refer to “young” and “old” mPer1-/- mCry2-/- animals on the basis of rhythmic or arrhythmic behavior, respectively.

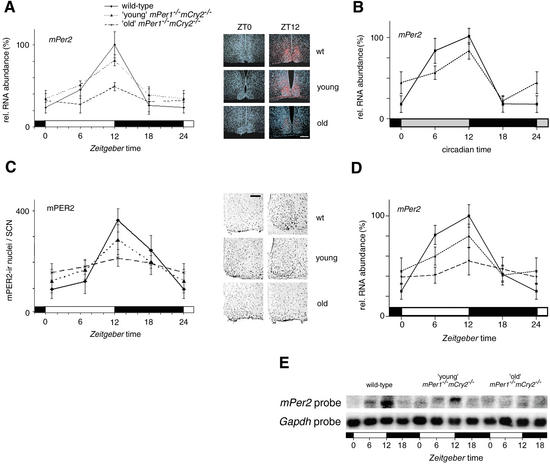

mPer2 mRNA expression in the SCN of young mPer1-/- mCry2-/- mice was comparable to that of wild-type animals under both LD and DD conditions with peak levels at Zeitgeber time (ZT) and circadian time (CT) 12, respectively (Fig. 2A,B). Interestingly, rhythmic mPer2 mRNA expression was severely blunted in the SCN of old mPer1-/- mCry2-/- mice (Fig. 2A). As mPer2 expression in old (6–12 mo) mPer1-/- and mCry2-/- single-mutant mice did not show a detectable reduction in amplitude under LD and DD conditions (Supplementary Fig. 3A,B), we conclude that the age-related loss of mPer2 mRNA oscillation in mPer1-/- mCry2-/- animals is characteristic for the double-knockout status. Analysis of the peripheral circadian oscillator in the kidney revealed a normal mPer2 mRNA expression profile in young mPer1-/- mCry2-/- mice kept under LD conditions, with maximal expression observed around ZT12 (Fig. 2D,E). In line with the data observed for the SCN, cyclic mPer2 mRNA expression in the kidney is blunted in old mPer1-/- mCry2-/- mice (Fig. 2D,E). In conclusion, circadian oscillators lacking both mPer1 and mCry2 appear sensitive to aging.

Figure 2.

mPer2 mRNA and mPER2 protein expression profiles of young and old mPer1-/- mCry2-/- mice. (A) Diurnal expression of mPer2 in the SCN of wild-type (solid line), young mPer1-/- mCry2-/- (dotted line), and old mPer1-/- mCry2-/- (dashed line) mice in LD. In old double mutants, mPer2 cycling is significantly dampened (p < 0.05). The black and white bars on the X-axis indicate the dark and light phases, respectively. All data presented are mean ± S.D. for three different experiments. (Right panels) Representative micrographs of SCN probed with an mPer2 antisense probe at time points of minimal(ZT0) and maximal(ZT12) expression. Tissue was visualized by Hoechst dye nuclear staining (blue); silver grains are artificially colored (red) for clarification. Bar, 200 μm. (B) Circadian expression of mPer2 in the SCN of wild-type (solid line) and young mPer1-/- mCry2-/- (dotted line) mice on the fourth day in DD. Gray and black bars on the X-axis indicate subjective day and night, respectively. (C) Diurnal variation of mPER2 immunoreactivity in the SCN of wild-type (solid line), young mPer1-/- mCry2-/- (dotted line), and old mPer1-/- mCry2-/- (dashed line) mice in LD. Quantification was performed by counting immunoreactive nuclei in the area of the SCN. In old double mutants, oscillation of mPER2 immunoreactivity is significantly dampened (p < 0.05) with medium numbers of immunoreactive nuclei. (Right panels) Representative micrographs of immunostained SCN at time points of minimal(ZT0) and maximal(ZT12) immunoreactivity. Bar, 100 μm. (D) Quantified Northern analysis of diurnal expression of mPer2 in the kidney of wild-type (solid line), young mPer1-/- mCry2-/- (dotted line), and old mPer1-/- mCry2-/- (dashed line) mice in LD. (E) Representative Northern blot from kidney tissue from wild-type (left), young mPer1-/- mCry2-/- (middle), and old mPer1-/- mCry2-/- (right) mice sequentially hybridized with mPer2 (top row) and Gapdh (bottom row) antisense probes. The black and white bars below the blots indicate dark and light phase, respectively.

To correlate mRNA expression to protein levels, we examined the presence of mPER2 protein in the SCN by immunohistochemistry. In wild-type and young mPer1-/- mCry2-/- mice, protein levels are high between ZT12 and ZT18 (Fig. 2C; Field et al. 2000), which is a few hours later than mRNA expression (Fig. 2A). In old mPer1-/- mCry2-/- mice, however, protein levels are low comparable to mRNA expression (Fig. 2A,C).

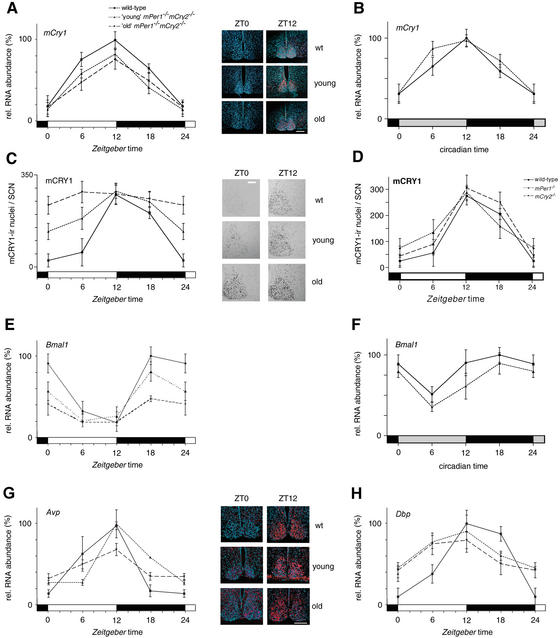

mPER1/2 and mCRY1/2 proteins inhibit CLOCK/BMAL1-mediated transcriptional activation (Kume et al. 1999; Lee et al. 2001). Therefore, we investigated the expression pattern of mCry1 in the SCN in mPer1-/- mCry2-/- mice. mCry1 mRNA expression profiles peak at ZT12 and CT12 under LD and DD conditions, respectively (Fig. 3A,B; Okamura et al. 1999). Similar expression patterns were observed in mPer1-/-, mCry2-/-, and young mPer1-/- mCry2-/- mice (Fig. 3A,B; Supplementary Fig. 3C,D). Interestingly, mCry1 mRNA levels displayed normal cycling in old mPer1-/- mCry2-/- mice in LD (Fig. 3A), which is in marked contrast to the blunted mPer2 mRNA expression profile in these mice (Fig. 2A,B). We thus examined mCRY1 protein levels in the SCN by immunohistochemistry. In wild-type animals, mCRY1 protein levels are oscillating with peak expression between ZT12 and ZT18 (Fig. 3C), as reported previously (Field et al. 2000). Similarly, young mPer1-/- mCry2-/- mice displayed cycling expression of mCRY1 protein, but the trough mCRY1 protein levels (at ZT24) were higher than in wild-type animals (Fig. 3C). Strikingly, expression of mCRY1 protein became totally blunted in old mPer1-/- mCry2-/- mice, leading to almost constant high levels of mCRY1 protein throughout the 24-h LD cycle (Fig. 3C). Note that age-matched mPer1-/- and mCry2-/- single-mutant mice display normal mCRY1 protein cycling (Fig. 3D).

Figure 3.

mCry1 and Bmal1 mRNA, and mCRY1 protein expression profiles of wild-type (solid line), young mPer1-/- mCry2-/- (dotted line), and old mPer1-/- mCry2-/- (dashed line) mice. (A) Diurnal expression of mCry1 in the SCN in LD. The black and white bars on the X-axis indicate dark and light phases, respectively. (Right panels) Representative micrographs of SCN probed with the mCry1 antisense probe at time points of minimal(ZT0) and maximal(ZT12) expression. Bar, 200 μm. (B) Circadian expression of mCry1 in the SCN on the fourth day in DD. The gray and black bars on the X-axis indicate subjective day and night, respectively. (C) Diurnal variation of mCRY1 immunoreactivity in the SCN in LD. Quantification was performed by counting immunoreactive nuclei in the area of the SCN. In old double mutants, oscillation of mCRY1 immunoreactivity is significantly dampened (p < 0.05), with constantly high numbers of immunoreactive nuclei throughout the LD cycle. (Right panels) Representative micrographs of immunostained SCN at time points of minimal(ZT0) and maximal(ZT12) immunoreactivity. Bar, 100 μm. (D) Diurnal expression of mCRY1 protein in the SCN of wild-type (solid line), mPer1-/- (dotted line), and mCry2-/- (hatched line) mice. (E) Diurnal variation of Bmal1 mRNA expression in the SCN in LD. In old double mutants, Bmal1 cycling is significantly dampened (p < 0.05). (F) Circadian expression of Bmal1 mRNA in the SCN on the fourth day in DD. (G) Diurnal time course of Avp mRNA expression in the SCN in LD. (H) Diurnal time course of Dbp mRNA expression in the SCN in LD. Tissue was visualized by Hoechst dye nuclear staining (blue); silver grains are artificially colored (red) for clarification. All data presented are mean ± S.D. for three different experiments.

We looked at Bmal1 mRNA expression, a clock component of the positive limb, under LD and DD conditions. In wild-type and mPer1-/- animals, a maximum was seen at ZT and CT 18 in the SCN (Supplementary Fig. 3E,F) as previously observed (Honma et al. 1998). In mCry2-/- animals, the maximum of Bmal1 expression was slightly delayed (Supplementary Fig. 3E,F). Young mPer1-/- mCry2-/- animals displayed a wild-type expression pattern, although the peak levels tended to be slightly decreased (Fig. 3E,F). In old mPer1-/- mCry2-/- mice, Bmal1 mRNA levels were significantly blunted (Fig. 3E).

Because expression of core clock components is altered in old mPer1-/- mCry2-/- animals, we investigated whether this translates into a change in expression of output genes. Arginine-vasopressin (Avp) expression is significantly reduced in old mPer1-/- mCry2-/- animals (Fig. 3G), indicating physiological consequences linked to the aging process. mPer1 and mCry2 mutant mice do not exhibit this change in Avp expression (Albrecht and Oster 2001; Supplementary Fig. 3G). Dbp expression appeared also to be affected (Fig. 3H); however, this change is caused by the Cry2 inactivation (Supplementary Fig. 3H) and is not specific to the Per1 Cry2 double mutation.

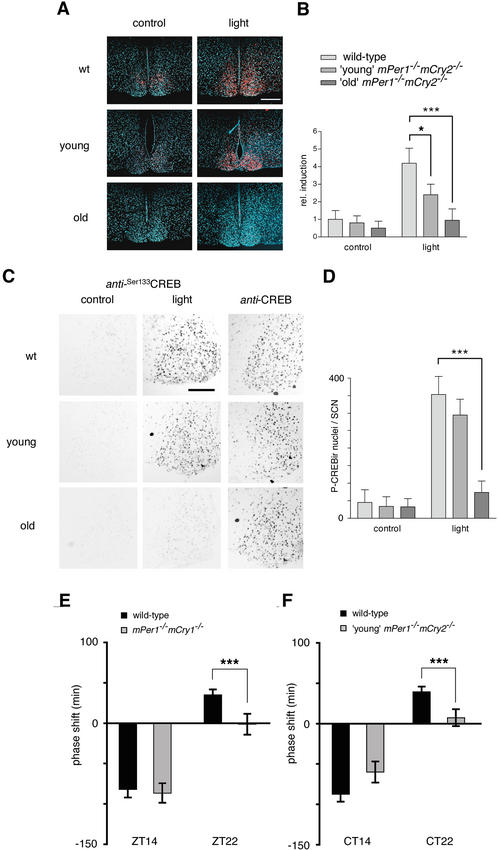

Loss of light inducibility of mPer2 mRNA and effect on delaying the clock phase in mPer1-/- mCry2-/- mice

mPer expression can also be induced by phase-resetting light stimuli via the CREB signaling pathway (Motzkus et al. 2000; Travnickova-Bendova et al. 2002). To investigate whether aging affects light inducibility of the mPer2 gene in the SCN of mPer1-/- mCry2-/- mice, we exposed young and old animals to a 15-min nocturnal light pulse at ZT14. Interestingly, induction of mPer2 mRNA was significantly impaired in young mPer1-/- mCry2-/- mice when compared with wild-type animals (p < 0.05; Fig. 4A,B). This defect was even more pronounced in old mPer1-/- mCry2-/- mice (p < 0.001; Fig. 4A,B), indicating that the light signal transduction path-way might be affected. Therefore we set out to investigate light-dependent phosphorylation of CREB at position 133 (CREB-Ser133). We found that in wild-type animals, phosphorylation at CREB-Ser133 was induced by light (Fig. 4C,D) as described previously (von Gall et al. 1998). Young mPer1-/- mCry2-/- animals tended to show a slight (but statistically not significant) reduction in phosphorylation of CREB-Ser133 (Fig. 4C,D). In contrast, old mPer1-/- mCry2-/- mice hardly displayed phosphorylation at CREB-Ser133 (p < 0.001; Fig. 4C,D), suggesting a degeneration of the light input pathway to the clock.

Figure 4.

Light responsiveness in the SCN of young and old mPer1-/- mCry2-/- mice. (A) In situ hybridization analysis of mPer2 light inducibility in the SCN of wild-type (wt, top row), young mPer1-/- mCry2-/- (middle row), and old mPer1-/- mCry2-/- mice (bottom row). Shown are representative micrographs of SCN probed with an mPer2 antisense probe with (light) or without light administration (control) at ZT14 (15-min light pulse, 400 lx; animals were sacrificed 1 h later). Tissue was visualized by Hoechst dye nuclear staining (blue); silver grains are artificially colored (red) for clarification. Bar, 200 μm. (B) Quantification of mPer2 induction after a light pulse at Z14. (Left panel) Control animals without light exposure. (Right panel) Relative mPer2 mRNA induction after light exposure (wild-type control was set as 1). Data presented are mean ± S.D. of three different animals each. Statistical significance is indicated by asterisks (*, p < 0.05; ***, p < 0.001). (C) Immunohistochemistry analysis of CREB Ser 133 phosphorylation by light in the SCN of wild-type (wt, top row), young mPer1-/- mCry2-/- (middle row), and old mPer1-/- mCry2-/- mice (bottom row). Shown are representative micrographs of SCN sections immunostained for Ser133P-CREB with (light) or without light administration (control) at ZT14. As a control, SCN sections for all genotypes were stained for CREB (unphosphorylated) at the same time points. (D) Quantification of CREB phosphorylation after a light pulse at ZT14. Panels show numbers of Ser133P-CREB immunoreactive nuclei in the SCN with or without light exposure (***, p < 0.001). (E) Light-induced phase shifts in mPer1-/- mCry1-/- mice using the Aschoff Type II protocol to assess phase shifts. Animals were kept for at least 10 d in LD and released into DD after a light pulse at ZT14 or ZT22. Negative values indicate phase delays; positive values indicate phase advances. The data presented are mean ± S.D. of 10–14 animals (***, p < 0.001). (F) Light-induced phase shifts in young mPer1-/- mCry2-/- mice using the Aschoff Type I protocolto assess phase shifts. Animals were kept for at least 10 d in DD before a light pulse at CT14 or CT22. Data presented are mean ± S.D. of 10–13 animals.

Given the aberrant light-mediated mPer2 mRNA induction and CREB-Ser133 phosphorylation in mPer1-/- mCry2-/- mice, we next wanted to investigate whether this had behavioral consequences. We monitored wheel-running activity before and after a 15-min light pulse at ZT14 or ZT22 as well as at CT14 or CT22 and measured the magnitude of phase shifts (Fig. 4E,F). In wild-type animals, we observed a phase delay at ZT14 of 82 ± 10 min (mean ± S.D., n = 14) and 87.3 ± 9.3 min (n = 14) at CT14 and a phase advance of 35 ± 6.7 min (n = 14) at ZT22 and 39.3 ± 6.7 min (n = 14) at CT22. In mPer1-/- mCry2-/- animals, only the phase shifts for young animals could be determined because the arrhythmicity of old mPer1-/- mCry2-/- animals in DD precludes such experiments. mPer1-/- mCry1-/- mice delayed their phase at ZT14 similar to wild-type animals (86.5 ± 12 min; n = 11; Fig. 4E). Remarkably, in mPer1-/- mCry2-/- mice, phase delays at CT14 tended to be reduced (60 ± 13 min; with p = 0.0539, n = 10), missing the criterion of p < 0.05 for significance (Fig. 4F). However, at ZT22 and CT22 phase advances in both mPer1/mCry1 (1.3 ± 13 min; n = 11) and mPer1/mCry2 (7.3 ± 10.5 min; n = 10), double-mutant animals were abolished (Fig. 4E,F), which is comparable to the inability of mPer1-/- mice to advance clock phase after a 15-min light pulse (Albrecht et al. 2001). These results suggest that the defect in advancing clock phase is caused by a lack of mPer1 in both mPer1-/- mCry1-/- and mPer1-/- mCry2-/- mice. The impairment of delaying clock phase in mPer1-/- mCry2-/- mice at CT14 is probably caused by a reduction of phosphorylation in CREB-Ser133 and reduced expression of mPer2 mRNA. This is in line with previous findings that mPer2 mutant mice are defective in delaying clock phase (Albrecht et al. 2001).

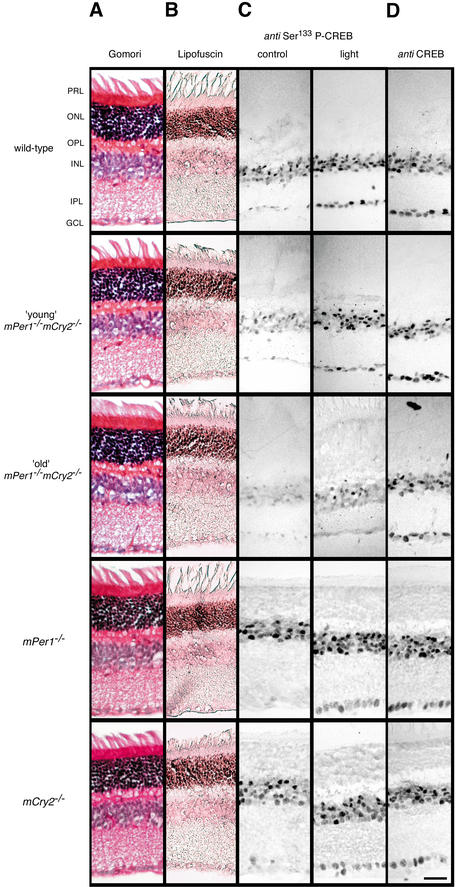

CREB phosphorylation at Ser 133 is decreased in the eye of mPer1-/- mCry2-/- mice

The sloppy onset of wheel-running activity in LD and the strong reduction in CREB phosphorylation at Ser 133 in the SCN of old mPer1-/- mCry2-/- mice indicated that light signaling from the eye to the SCN might be defective. We therefore performed a histochemical analysis of the retina from wild-type, mPer1-/-, mCry2-/-, and mPer1-/- mCry2-/- mice, respectively (Fig. 5). No overt morphological differences between the retinas of these mice or cell death could be detected (Fig. 5A,B). Thus, the observed effects of aging in mPer1-/- mCry2-/- animals appear restricted to the functionality of the circadian system and are not likely to originate from aberrant development or age-related morphological changes in the retina.

Figure 5.

Histology and light responsiveness in the retina of wild-type, young, and old mPer1-/- mCry2-/- mice. Gomori trichrome (A) and lipofuscin (B) staining of retinal sections of wild-type (first row), young mPer1-/- mCry2-/- (second row), old mPer1-/- mCry2-/- (third row), mPer1-/- (fourth row), and mCry2-/- mice (fifth row). Retinal layers are indicated on the left. PRL, potoreceptor layer; ONL, outer nuclear layer; OPL, outer plexiform layer; INL, inner nuclear layer; IPL, inner plexiform layer; GCL, ganglion cell layer. (C) Immunohistochemistry analysis of light-induced CREB Ser 133 phosphorylation in the retina. (Left panels) Immunostained retinal sections of control animals without light exposure. (Right panels) Animals 1 h after light exposure (400 lx, 15 min) at ZT14. (D) Immunohistochemistry analysis for (unphosphorylated) CREB in the retina at ZT14. Bar, 10 μm.

Next we investigated phosphorylation of CREB at serine residue 133 in the retina by using an anti-Ser133 P-CREB antibody (Fig. 5C). In wild-type animals, in the absence of light stimuli, Ser133 P-CREB was detected in the inner nuclear layer. A light pulse given at ZT14 has been shown to result in increased numbers of immunoreactive nuclei in the inner nuclear layer and ganglion cell layer (Gau et al. 2002). In mPer1-/- and mCry2-/- single-mutant animals and in young mPer1-/- mCry2-/- mice, a similar immunoreactivity was seen (Fig. 5C). Old mPer1-/- mCry2-/- animals, however, displayed a reduced number of immunoreactive nuclei in the inner nuclear layer after a light pulse, whereas Ser133 P-CREB staining could hardly be observed in the ganglion cell layer (Fig. 5C). Taken together, these results indicate that the profound loss of circadian wheel-running behavior of old mPer1-/- mCry2-/- mice under LD conditions (Fig. 1F) is caused by impaired light signal transduction pathway performance in combination with an age-related decline in core oscillator function.

Discussion

Interaction of clock components has predominantly been investigated in vitro (Gekakis et al. 1998; Kume et al. 1999; Yagita et al. 2000, 2002), revealing that mPER and mCRY proteins can form complexes that influence nuclear transport or regulate transcription of clock components. In contrast, it is not known to what extent complexes composed of various combinations of mPER and mCRY proteins contribute to circadian oscillator performance in vivo. We thus started to conduct genetic experiments by crossing mouse strains with inactivated mPer or mCry genes and subsequently analyzing circadian behavior, clock gene, and protein expression. mPer1-/- mCry1-/- mice display normal circadian rhythmicity but show impaired ability to phase advance the clock

We have shown that mPer1-/- mCry1-/- mice, in contrast to short-period mCry1-/- mice, display a period length comparable to that of wild-type littermates (Fig. 1B,C). Thus, the additional loss of mPer1 in mCry1-/- mice leads to an increase in period length to near normal values in DD (23.7 ± 0.2 h for mPer1-/- mCry1-/- mice vs. 22.51 ± 0.06 h for Cry1-/- mice). This also indicates that expression of the mPER2 and mCRY2 proteins apparently is sufficient to maintain circadian rhythmicity. The rescue of the mCry1-/- phenotype by additional loss of the mPer1 gene is also reflected at the molecular level, where mPer2 and Bmal1 show normal mRNA rhythms under both LD and DD conditions (see Supplementary Fig. 1). Hence mPer1 acts as a nonallelic suppressor of mCry1. Interestingly, mPer1-/- mCry1-/- animals could not phase advance their behavioral rhythms after a 15-min light pulse given at ZT22 (Fig. 4E), and in this respect resemble mPer1-/- animals (Albrecht et al. 2001). In conclusion, only circadian core clock functionality is rescued by an inactivation of mCry1 in mPer1-/- mice, but not the resetting properties of the clock. Breakdown of the clock in aging mPer1-/- mCry2-/- mice

Circadian organization changes with age (Valentinuzzi et al. 1997; Yamazaki et al. 2002). Typical changes include decrease in the amplitude of wheel-running activity, fragmentation of the activity rhythm, decreased precision in onset of daily activity, and alterations in the response to the phase-shifting effects of light (Valentinuzzi et al. 1997). In mice, aging has been found to diminish the amplitude of Per2 but not Per1 expression (Weinert et al. 2001).

Here, we provide evidence that a clock defect can make the circadian oscillator fall apart more quickly, resembling accelerated aging. Inactivation of mPer1 and mCry2 in young mPer1-/- mCry2-/- mice (2–6 mo old) leads to a decreased precision in onset of daily activity (Fig. 1D,E). Additionally, onset of activity is markedly delayed, with a sharp offset at the dark/light transition probably reflecting masking (Mrosovsky 1999). In old mPer1-/- mCry2-/- mice, the precision in onset of daily activity is even further deteriorated (Fig. 1F). Moreover, animals start to display fragmentation of activity under LD conditions, and daily rhythms become barely detectable (Fig. 1G). In constant darkness, old mPer1-/- mCry2-/- mice no longer display circadian rhythmicity, and the amplitude of wheel-running activity is decreased compared with that of wild-type and young mPer1-/- mCry2-/- mice (Fig. 1F,I). The percentage of arrhythmic mPer1-/- mCry2-/- mice increases with age (Fig. 1H), but the time of onset of the arrhythmic circadian phenotype varies among animals, indicating that additional genes or genetic background may contribute to the aging process. All these features are observed neither in mPer1-/- and mCry2-/- single-mutant mice (van der Horst et al. 1999; Zheng et al. 2001; Supplementary Fig. 2) nor in mPer1-/- mCry1-/-, mPer2Brdm1 mCry1-/-, mPer2Brdm1 mCry2-/- (Supplementary Fig. 2D), or heterozygous mPer1 mCry1 and mPer1 mCry2 mice (Supplementary Fig. 4).

Gene expression is known to change upon aging. Alterations in mRNA and protein levels can result from changes in transcriptional regulation (Roy et al. 2002), mRNA stability (Brewer 2002), and proteasome-mediated protein degradation (Goto et al. 2001). We have shown that the absence of mPer1 and mCry2 specifically alters the regulation of the circadian core oscillator in an age-related manner. This is illustrated by our observation that mPer2 and Bmal1 mRNA levels are strongly reduced in the SCN and in the kidney of old mPer1-/- mCry2-/- mice (Figs. 2, 3E,F). Additionally, mCRY1 protein levels are elevated (Fig. 3C), pointing to an impaired degradation of mCRY1 protein. Interestingly, mCry1 mRNA cycling is not affected in contrast to mPer2 and Bmal1 transcripts, indicating that regulation of mCry1 differs from that of mPer2 and Bmal1. Old mPer1-/- mCry2-/- mice display not only altered gene expression of core clock components but also altered expression of the clock output gene arginine-vasopressin (Avp; Fig. 3G), indicating that physiological pathways influenced by Avp are affected in these mice. Interestingly, Dbp seems to be regulated differently, because its gene expression is already altered in mCry2-/- mice (Fig. 3H; Supplementary Fig. 3H).

Light sensitivity is impaired in aging mPer1-/- mCry2-/- mice

Old mPer1-/- mCry2-/- mice synchronize poorly to the light dark cycle (Fig. 1F). Therefore, we tested whether CREB, an essential factor for numerous transcriptional processes, was activated by phosphorylation in response to a light pulse (Motzkus et al. 2000; Travnickova-Bendova et al. 2002). CREB phosphorylation was only slightly lowered in young mPer1-/- mCry2-/- mice but was significantly impaired in old animals (Fig. 4C,D), indicating a defect in light signaling in the SCN of these mice. At the behavioral level, we could only measure the phase shifts of young mPer1-/- mCry2-/- mice, because old animals immediately became arrhythmic in DD. The young mPer1-/- mCry2-/- mice resemble mPer1-/- animals in that they were not able to advance clock phase (Fig. 4F; Albrecht et al. 2001), suggesting that this anomaly is due to the absence of mPer1.

The impaired light response of mPer1-/- mCry2-/- mice might be a consequence of a defect in transmitting light information from the eye to the SCN. To test this possibility, we looked for anatomical malformations in the retina. Neither young nor old mPer1-/- mCry2-/- mice displayed overt abnormalities in retinal morphology (Fig. 5A). Cell death as a reason for malfunction of the retina could most possibly be excluded, because lipofuscin staining (Fig. 5B) and Congo red staining (data not shown) did not reveal dead cells in the retina. Comparable to the SCN, however, light-dependent phosphorylation of CREB at Ser 133 was affected in old mPer1-/- mCry2-/- mice (Fig. 5C). As a consequence, light perceived by the eye is probably not processed properly to induce cellular signaling. The reason for the impaired transmission of the light signal is most likely not a developmental defect, because young mPer1-/- mCry2-/- mice show phosphorylation of CREB at Ser 133. Therefore, the defect is probably of transcriptional or posttranscriptional nature. The lack of phosphorylation of CREB might lead to an altered expression of melanopsin in ganglion cells. These cells are probably responsible for resetting of the clock by light (Berson et al. 2002; Hattar et al. 2002). Hence, a reduced expression of melanopsin would affect resetting. This is in line with the recent finding, that melanopsin-deficient mice display attenuated clock resetting in response to brief light pulses (Panda et al. 2002; Ruby et al. 2002), similar to what we observe in mPer1-/- mCry2-/- mice (Fig. 4F). In old mPer1-/- mCry2-/- mice, this might even lead to the poor synchronization of these mice to the LD cycle (Fig. 1F,G). Future studies will reveal whether melanopsin expression in ganglion cells of the retina is affected in old mPer1-/- mCry2-/- mice. The transcriptional potential of mPER and mCRY protein complexes and their temporal abundance determines circadian rhythmicity

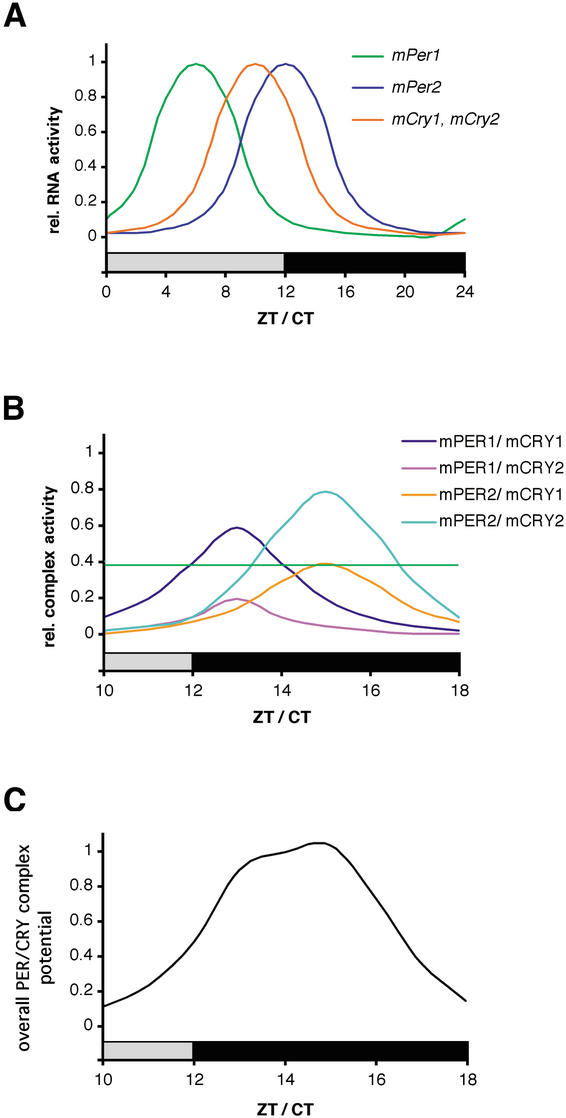

The precise regulation of the circadian oscillator requires an exact choreography of clock protein synthesis, interaction, posttranslational modification, and nuclear localization (Lee et al. 2001; Yagita et al. 2002). The positive limb of circadian clock gene activation is influenced by the negative limb via REV-ERBα (Preitner et al. 2002), probably through a complex consisting of mPER and mCRY proteins (Albrecht 2002; Okamura et al. 2002; Yu et al. 2002). The mPER and mCRY proteins stabilize each other when they are in a complex and inhibit the CLOCK/BMAL1 heterodimer. Such a mPER/mCRY complex would be composed of those PER and CRY proteins that are most abundant at a given time. Figure 6A depicts the temporal abundance of cycling mPer1, mPer2, mCry1, and mCry2 mRNA in the SCN, illustrating that the amount of mRNA of these genes differs with time (Albrecht et al. 1997; Okamura et al. 1999; Reppert and Weaver 2002; Yan and Okamura 2002). Because the clock components of the negative limb (Per and Cry) are regulating their own transcription, the mRNA cycling is likely to reflect the activity of the corresponding proteins. The active forms of PER and CRY proteins seem to be cycling with a delay of 4–6 h compared with mRNA (Field et al. 2000).

Figure 6.

Working model for PER/CRY-driven inhibition of CLOCK/BMAL1. (A) mPer and mCry transcripts show diurnal/circadian cycling in the SCN. Whereas mPer1 expression peaks between ZT/CT 4 and 8, mCry1 and mPer2 mRNA rhythms have their maxima at ZT/CT10 to ZT/CT12, respectively. Note that mCry2 is also expressed in the SCN but without a clearly defined rhythm. Protein peaks are delayed by ∼4–6 h with regard to mRNA. (B) mPER and mCRY proteins form heteromeric complexes that form with certain preferences according to protein–protein affinity and temporal abundance. The complexes are color coded, with mPER1/mCRY1 and mPER2/mCRY2 representing the most abundant ones. The green horizontal line indicates a threshold above which a PER/CRY complex is abundant enough to influence CLOCK/BMAL1 transcription. (C) Time course of the overall inhibitory potential of the mPER/mCRY heteromers on CLOCK/BMAL1 activity. The strong inhibition of CLOCK/BMAL1 during (subjective) night corresponds to the low transcriptional activity of (CLOCK/BMAL1-induced) mPer and mCry genes.

Interestingly, not all PER/CRY complexes seem to be equally important in vivo (Oster et al. 2002; this study). mPer2Brdm1 mCry2-/- mutant but not mPer2Brdm1 mCry1-/- mutant mice display circadian rhythmic behavior, indicating that mPER1/mCRY1 but not mPER1/mCRY2 is sufficient to drive the circadian clock (Oster et al. 2002). This study indicates that mPER2/mCRY2 but—at least in older mice—not mPER2/mCRY1 can sustain circadian rhythms. Additionally, mPer1-/- mPer2Brdm1 and mCry1-/- mCry2-/- double-mutant mice do not show circadian rhythmicity, indicating that mPER or mCRY homodimers are not sufficient to maintain circadian rhythmicity. Based on these observations, we propose activity and timing of PER/CRY complexes as illustrated in Figure 6B. According to this model, the complexes composed of mPER1/mCRY1 and mPER2/mCRY2 would be the most active ones, with a difference in their maxima of ∼2 h. The activity of these complexes is higher than a critical threshold level necessary to drive clock regulation (green horizontal line in Fig. 6B). In contrast, mPER1/mCRY2 complexes formed in Per2/Cry1 mutant mice probably do not reach this critical threshold. The reason for this might be that the timing of expression of these two proteins is not synchronized and/or the affinity between mPER1 and mCRY2 is low. As a consequence, Per2/Cry1 mutant mice lose clock function (Oster et al. 2002). The complex containing mPER2 and mCRY1 seems to just reach the critical threshold necessary for clock regulation, as illustrated by the circadian wheel-running behavior of young mPer1-/- mCry2-/- mice (Fig. 1D,E). However, with progressing age, the activity of such a complex falls below the threshold, and hence, older mPer1-/- mCry2-/- mice lose rhythmicity (Fig. 1F,I). mPer2Brdm1 mutant mice lose circadian rhythmicity after a few days in constant darkness. In these animals only functional mPER1/mCRY1 and mPER1/mCRY2 complexes can form, which should in principle be sufficient to drive a circadian rhythm. This seems to be the case for the first few days in constant darkness, but then competition between mCRY1 and mCRY2 for PER1 could lead to equal amounts of PER1/CRY1 and PER1/CRY2 complexes. The activity of each of these complexes might then fall below the threshold critical for normalclock function.

In sum, it seems that PER/CRY complexes have different potentials to regulate the circadian clock. In wild-type animals, the formation of PER/CRY complexes is not random and depends on temporal abundance and strength of interaction between the complex-forming partners (Fig. 6B). The sum of the regulatory potential of PER/CRY complexes over time displays a robust circadian cycling, as illustrated in Figure 6C. The robustness of this cycling may be ensured by the different phasing of the oscillation of the two strong regulatory complexes PER1/CRY1 and PER2/CRY2. This notion is supported by theoretical considerations indicating that an overt oscillation is stabilized by two oscillators that are slightly out of phase (Glass and Mackey 1988; Roenneberg and Merrow 2001). Our findings are also in agreement with the two-oscillator model proposed by Daan and coworkers (2001).

Taken together, our in vivo studies support a model based on differential presence and activity of PER/CRY protein complexes as critical regulators of circadian rhythmicity (Fig. 6). It is reasonable to conclude that not all interactions between PER and CRY proteins are equal in vivo. Although these proteins seem to be partially redundant, all of them are necessary for a functional circadian clock that can predict time and thereby be adaptable to changing environmental conditions. The importance of PER1 and CRY2 only becomes apparent in mPer1-/- mCry2-/- mice half a year after birth, illustrating a connection between the clock and aspects of aging.

Materials and methods

Generation of mPer and mCry mutant mice

We crossed mPer1-/- mice (Zheng et al. 2001) with mCry1-/- and mCry2-/- animals (van der Horst et al. 1999). The genotype of the offspring was determined by Southern blot analysis as described (Oster et al. 2002). Hybridization probes were for mPer1 as described in Zheng et al. (2001) and for mCry1 and mCry2 as described in van der Horst et al. (1999). Matching wild-type control animals were produced by back-crossing heterozygous animals derived from the mPer1-/- and mCry-/- matings to minimize epigenetic effects.

Locomotor activity monitoring and circadian phenotype analysis

Mice housing and handling were performed as described (Albrecht and Oster 2001; Albrecht and Foster 2002). For LD–DD transitions, lights were turned off at the end of the light phase and not turned on again the next morning. Activity records are double plotted so that each light/dark cycle's activity is shown both to the right and below that of the previous light/dark cycle. Activity is plotted in threshold format for 5-min bins. For activity counting and evaluation, we used the ClockLab software package (Actimetrics). Rhythmicity and period length were assessed by χ2 periodogram analysis and Fourier transformation using mice running in LD or in DD for at least 10 d.

For light-induced phase shifts, we used the Aschoff Type I (for mPer1-/- mCry1-/- animals) or the Type II protocol (for mPer1-/- mCry2-/- animals) as described (Albrecht and Oster 2001; Albrecht et al. 2001). We originally chose the Type II protocol because of the convenient setup for high numbers of animals and for comparison with mPer2Brdm1 mice (Albrecht et al. 2001; Oster et al. 2002). However, the unstable onset of activity of mPer1-/- mCry2-/- mice in LD and the long period length of these animals in DD resulted in very high variations when determining the phase shifts with the Type II protocol. Therefore, we repeated the experiments using a Type I setup with animals free running in DD before light administration. For the Type II protocol, animals were entrained to an LD cycle for at least 7 d before light administration (15 min of bright white light, 400 lx, at ZT14 or ZT22) and subsequently released into DD. The phase shift was determined by drawing a line through at least 7 consecutive days of onset of activity in LD before the light pulse and in DD after the light pulse as determined by the ClockLab program. The difference between the two lines on the day of the light pulse determined the value of the phase shift. For the Type I protocol, animals were kept in DD for at least 10 d before the light pulse (at CT14 or CT22, respectively). The phase shift was determined by drawing lines through at least 7 consecutive days before and after the light pulse using the ClockLab software. The first 1 or 2 d following the light administration were not used for the calculation because animals were thought to be in transition between both states.

In situ hybridization

Mice were sacrificed by cervical dislocation under ambient light conditions at ZT6 and ZT12 and under a 15W safety red light at ZT18 and ZT0/24 as well as at CT0/24, 6, 12, and 18. For DD conditions, animals were kept in the dark for 3 d before decapitation. For light induction experiments, animals were exposed to a 15-min light pulse (400 lx) at ZT14 and killed at ZT15; controls were killed at ZT15 without prior light exposure. Specimen preparation, 35S-rUTP-labeled riboprobe synthesis, and hybridization steps were performed as described (Albrecht et al. 1998). The probe for mPer2 was as described (Albrecht et al. 1997). The mCry1 and the Bmal1 probes were as described (Oster et al. 2002). The Dbp probe was made from a cDNA corresponding to nucleotides 2–951 (GenBank accession no. NM016974). The vasopressin (Avp) probe corresponds to nucleotides 1–480 (GenBank accession no. M88354). Quantification was performed by densitometric analysis of autoradiograph films (Amersham Hyperfilm MP) as described (Oster et al. 2002). For each time point, three animals were used and three sections per SCN were analyzed. “Relative mRNA abundance” values were calculated by defining the highest value of each experiment as 100%.

Immunohistochemistry

Animals were killed and tissues were prepared as described for in situ hybridization. Eye lenses were removed before cutting. Sections were boiled in 0.01 M sodium citrate (pH 6) for 10 min to unmask hidden antigen epitopes and were processed for immunohistochemical detection using the Vectastain Elite ABC system (Vector Laboratories) and diaminobenzidine with nickel amplification as the chromogenic substrate. Immunostained sections were inspected with an Axioplan microscope (Zeiss), and the area of the SCN was determined by comparison to Nissl-stained parallel sections. Semiquantitative analysis for mCRY1, mPER2, and Ser133P-CREB immunoreactivity in the SCN was performed using the NIH Image program. Images were digitized; background staining was used to define a lower threshold. Within the whole area of the SCN, all cell nuclei exceeding the threshold value were marked. Three sections of the intermediate aspect of the SCN were chosen at random for further analysis. Values presented are the mean of three different experiments ±S.D. Primary antibodies against mCRY1 (Alpha Diagnostics, order number CRY11-A), against CREB (Cell Signaling Technology, order no. 9192), against CREB, phosphorylated at the residue Ser 133 (New England Biolabs, order no. 9191S), and against mPER2 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, order no. sc-7729) were used at dilutions of 1:200, 1:500, 1:1000, and 1:200, respectively.

Northern blot analysis

Rhythmic animals were sacrificed at the specified time points. Total RNA from kidney was extracted using RNAzol B (WAK Chemie). Northern analysis was performed using denaturing formaldehyde gels (Sambrook and Russell 2001), with subsequent transfer to Hybond-N+ membrane (Amersham). For each sample, 20 μg of total RNA was used. cDNA probes were the same as described for in situ hybridization. Labeling of probes was done using the Rediprime II labeling kit (Pharmacia) incorporating [32P]dCTP to a specific activity of 108 cpm/μg. Blots were hybridized using UltraHyb solution (Ambion) containing 100 μg/mL salmon sperm DNA. The membrane was washed at 60°C in 0.1× SSPE and 0.1% SDS. Subsequently, blots were exposed to phosphoimager plates (Bio-Rad) for 20 h, and signals were quantified using Quantity One 3.0 software (Bio-Rad). For comparative purposes, the same blot was stripped and reused for hybridization. The relative level of RNA in each lane was determined by hybridization with mouse Gapdh cDNA.

Histology

All histological staining was performed as described (Burkett et al. 1993). For Gomori's trichrome staining, PFA-fixed, paraffin-embedded sections were dewaxed, and postfixed with Bouin's fluid at 56°C for 30 min; nuclei were stained with ferric haematoxyline (according to Weigert) for 10 min. After washing in water, slides were incubated for 15 min with trichrome stain [Chromotrope 2R, 0.6% (w/v), and Light Green, 0.3% (w/v), in 1% (v/v) acetic acid and 0.8% (w/v) phosphotungstic acid]. After washing with 0.5% acetic acid and 1% (v/v) acetic acid/0.7% (w/v) phosphotungstic acid, slides were rinsed with water, dehydrated, and mounted with Canada balsam/methyl salycilate.

For lipofuscin staining, slides were dewaxed and colored with 0.75% (w/v) ferric chloride/0.1% (w/v) potassium ferricyanide (Aldrich) for 5 min. After washing with 1% (v/v) acetic acid and water, slides were incubated with 1% (w/v) Neutral Red for 3–4 min and subsequently washed with water, dehydrated, and mounted with Dpx mounting media (Fluka). All reagents were from Sigma if not stated otherwise.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis of all experiments was performed using GraphPad Prism software (GraphPad). Significant differences between groups were determined with one-way ANOVA, followed by Bonferroni's post-test. Values were considered significantly different with p < 0.05 (*), p < 0.01 (**), or p < 0.001 (***).

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a SPINOZA premium from the Netherlands Organisation for Scientific Research (NWO) to G.T.J.v.d.H. and the Swiss National Science Foundation, the State of Fribourg, the Novartis Foundation, the AETAS Foundation for Research into Aging, and the Hans Wilsdorf Foundation in Geneva to U.A. This research has been part of the Brain-Time project (QLRT-2001-01829) funded by the European Community and the Swiss Office for Education and Research.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by payment of page charges. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

Corresponding author.

Article and publication are at http://www.genesdev.org/cgi/doi/10.1101/gad.256103.

Footnotes

Supplemental material is available at http://www.genesdev.org.

References

- Albrecht U. 2002. Invited Review: Regulation of mammalian circadian clock genes. J. Appl. Physiol. 92: 1348–1355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Albrecht U. and Foster, R.G. 2002. Placing ocular mutants into a functionalcontext: A chronobiological approach. Methods 28: 465–477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Albrecht U. and Oster, H. 2001. The circadian clock and behavior. Behav. Brain Res. 125: 89–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Albrecht U., Sun, Z.S., Eichele, G., and Lee, C.C. 1997. A differential response of two putative mammalian circadian regulators, mper1 and mper2, to light. Cell 91: 1055–1064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Albrecht U., Lu, H.-C., Revelli, J.-P., Xu, X.-C., Lotan, R., and Eichele, G. 1998. Studying gene expression on tissue sections using in situ hybridization. In Human genome methods (ed. K.W. Adolph), pp. 93–119. CRC Press, New York.

- Albrecht U., Zheng, B., Larkin, D., Sun, Z.S., and Lee, C.C. 2001. mper1 and mper2 are essential for normal resetting of the circadian clock. J. Biol. Rhythms 16: 100–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allada R., Emery, P., Takahashi, J.S., and Rosbash, M. 2001. Stopping time: The genetics of fly and mouse circadian clocks. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 24: 1091–1119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bae K., Jin, X., Maywood, E.S., Hastings, M.H., Reppert, S.M., and Weaver, D.R. 2001. Differential functions of mPer1, mPer2, and mPer3 in the SCN circadian clock. Neuron 30: 525–536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balsalobre A., Damiola, F., and Schibler, U. 1998. A serum shock induces circadian gene expression in mammalian tissue culture cells. Cell 93: 929–937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berson D.M., Dunn, F.A., and Takao, M. 2002. Phototransduction by retinal ganglion cells that set the circadian clock. Science 295: 1070–1073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brewer G. 2002. Messenger RNA decay during aging and development. Ageing Res. Rev. 1: 607–625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burkett H.G., Young, B., and Heath, J.W. 1993. Wheather's functional histology, 3 ed. Churchill Livingstone, London.

- Cermakian N., Monaco, L., Pando, M.P., Dierich, A., and Sassone-Corsi, P. 2001. Altered behavioral rhythms and clock gene expression in mice with a targeted mutation in the Period1 gene. EMBO J. 20: 3967–3974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daan S., Albrecht, U., van der Horst, G.T., Illnerova, H., Roenneberg, T., Wehr, T. A., and Schwartz, W.J. 2001. Assembling a clock for all seasons: Are there M and E oscillators in the genes? J. Biol. Rhythms 16: 105–116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Field M.D., Maywood, E.S., O'Brien, J.A., Weaver, D.R., Reppert, S.M., and Hastings, M.H. 2000. Analysis of clock proteins in mouse SCN demonstrates phylogenetic divergence of the circadian clockwork and resetting mechanisms. Neuron 25: 437–447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gau D., Lemberger, T., von Gall, C., Kretz, O., Le Minh, N., Gass, P., Schmid, W., Schibler, U., Korf, H.W., and Schutz, G. 2002. Phosphorylation of CREB Ser142 regulates light-induced phase shifts of the circadian clock. Neuron 34: 245–253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gekakis N., Staknis, D., Nguyen, H.B., Davis, F.C., Wilsbacher, L.D., King, D.P., Takahashi, J.S., and Weitz, C.J. 1998. Role of the CLOCK protein in the mammalian circadian mechanism. Science 280: 1564–1569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glass L. and Mackey, M.C. 1988. From clocks to chaos—The rhythms of life. Princeton University Press, Princeton, NJ.

- Goto S., Takahashi, R., Kumiyama, A.A., Radak, Z., Hayashi, T., Takenouchi, M., and Abe, R. 2001. Implications of protein degradation in aging. Ann. NY Acad. Sci. 928: 54–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamada T., LeSauter, J., Venuti, J.M., and Silver, R. 2001. Expression of period genes: Rhythmic and nonrhythmic compartments of the suprachiasmatic nucleus pacemaker. J. Neurosci. 21: 7742–7750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hattar S., Liao, H.W., Takao, M., Berson, D.M., and Yau, K.W. 2002. Melanopsin-containing retinal ganglion cells: Architecture, projections, and intrinsic photosensitivity. Science 295: 1065–1069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Honma S., Ikeda, M., Abe, H., Tanahashi, Y., Namihira, M., Honma, K., and Nomura, M. 1998. Circadian oscillation of BMAL1, a partner of a mammalian clock gene Clock, in rat suprachiasmatic nucleus. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 250: 83–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacob N., Vuillez, P., Lakdhar-Ghazal, N., and Pevet, P. 1999. Does the intergeniculate leaflet play a role in the integration of the photoperiod by the suprachiasmatic nucleus? Brain Res. 828: 83–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jagota A., de la Iglesia, H.O., and Schwartz, W.J. 2000. Morning and evening circadian oscillations in the suprachiasmatic nucleus in vitro. Nat. Neurosci. 3: 372–376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kume K., Zylka, M.J., Sriram, S., Shearman, L.P., Weaver, D.R., Jin, X., Maywood, E.S., Hastings, M.H., and Reppert, S.M. 1999. mCRY1 and mCRY2 are essential components of the negative limb of the circadian clock feedback loop. Cell 98: 193–205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee C., Etchegaray, J.P., Cagampang, F.R., Loudon, A.S., and Reppert, S.M. 2001. Posttranslational mechanisms regulate the mammalian circadian clock. Cell 107: 855–867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyamoto Y. and Sancar, A. 1998. Vitamin B2-based blue-light photoreceptors in the retinohypothalamic tract as the photoactive pigments for setting the circadian clock in mammals. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 95: 6097–6102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyazaki K., Mesaki, M., and Ishida, N. 2001. Nuclear entry mechanism of rat PER2 (rPER2): Role of rPER2 in nuclear localization of CRY protein. Mol. Cell. Biol. 21: 6651–6659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Motzkus D., Maronde, E., Grunenberg, U., Lee, C.C., Forssmann, W., and Albrecht, U. 2000. The human PER1 gene is transcriptionally regulated by multiple signaling pathways. FEBS Lett. 486: 315–319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mrosovsky N. 1999. Masking: History, definitions, and measurement. Chronobiol. Int. 16: 415–429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okamura H., Miyake, S., Sumi, Y., Yamaguchi, S., Yasui, A., Muijtjens, M., Hoeijmakers, J.H., and van der Horst, G.T. 1999. Photic induction of mPer1 and mPer2 in cry-deficient mice lacking a biological clock. Science 286: 2531–2534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okamura H., Yamaguchi, S., and Yagita, K. 2002. Molecular machinery of the circadian clock in mammals. Cell Tissue Res. 309: 47–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oster H., Yasui, A., van der Horst, G. T., and Albrecht, U. 2002. Disruption of mCry2 restores circadian rhythmicity in mPer2 mutant mice. Genes & Dev. 16: 2633–2638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panda S., Sato, T.K., Castrucci, A.M., Rollag, M.D., DeGrip, W.J., Hogenesch, J.B., Provenico, I., and Kay, S.A. 2002. Melanopsin (Opn4) requirement for normallight-induced circadian phase shifting. Science 298: 2213–2216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pittendrigh C.S. 1993. Temporal organization: Reflections of a Darwinian clock-watcher. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 55: 16–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preitner N., Damiola, F., Lopez-Molina, L., Zakany, J., Duboule, D., Albrecht, U., and Schibler, U. 2002. The orphan nuclear receptor REV-ERBα controls circadian transcription within the positive limb of the mammalian circadian oscillator. Cell 110: 251–260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ralph M.R., Foster, R.G., Davis, F.C., and Menaker M. 1990. Transplanted suprachiasmatic nucleus determines circadian period. Science 247: 975–978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reppert S. and Weaver, D. 2002. Coordination of circadian timing in mammals. Nature 418: 935–941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roenneberg T. and Merrow, M. 2001. Circadian systems: Different levels of complexity. Philos. Trans. R Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 356: 1687–1696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roy A.K., Oh, T., Rivera, O., Mubiru, J., Song, C.S., and Chatterjee, B. 2002. Impacts of transcriptional regulation on aging and senescence. Ageing Res. Rev. 1: 367–380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruby N.F., Brennan, T.J., Xie, X., Cao, V., Franken, P., Heller, H.C., and O'Hara, B.F. 2002. Role of melanopsin in circadian responses to light. Science 298: 2211–2213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rusak B. and Zucker, I. 1979. Neural regulation of circadian rhythms. Physiol. Rev. 59: 449–526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sambrook J. and Russell, D.W. 2001. Molecular cloning: A laboratory manual, 3rd ed., Vol. 1. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY.

- Shearman L.P., Zylka, M.J., Weaver, D.R., Kolakowski Jr., L.F., and Reppert, S.M. 1997. Two period homologs: Circadian expression and photic regulation in the suprachiasmatic nuclei. Neuron 19: 1261–1269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shearman L.P., Jin, X., Lee, C., Reppert, S.M., and Weaver, D.R. 2000. Targeted disruption of the mPer3 gene: Subtle effects on circadian clock function. Mol. Cell. Biol. 20: 6269–6275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun Z.S., Albrecht, U., Zhuchenko, O., Bailey, J., Eichele, G., and Lee, C.C. 1997. RIGUI, a putative mammalian ortholog of the Drosophila period gene. Cell 90: 1003–1011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tei H., Okamura, H., Shigeyoshi, Y., Fukuhara, C., Ozawa, R., Hirose, M., and Sakaki, Y. 1997. Circadian oscillation of a mammalian homologue of the Drosophila period gene. Nature 389: 512–516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Travnickova-Bendova Z., Cermakian, N., Reppert, S.M., and Sassone-Corsi, P. 2002. Bimodal regulation of mPeriod promoters by CREB-dependent signaling and CLOCK/BMAL1 activity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 14: 14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valentinuzzi V.S., Scarbrough, K., Takahashi, J.S., and Turek, F.W. 1997. Effects of aging on the circadian rhythm of wheel-running activity in C57BL/6 mice. Am. J. Physiol. 273: R1957–R1964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Horst G.T., Muijtjens, M., Kobayashi, K., Takano, R., Kanno, S., Takao, M., de Wit, J., Verkerk, A., Eker, A.P., van Leenen, D., et al. 1999. Mammalian Cry1 and Cry2 are essential for maintenance of circadian rhythms. Nature 398: 627–630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vielhaber E.L., Duricka, D., Ullman, K.S., and Virshup, D.M. 2001. Nuclear export of mammalian PERIOD proteins. J. Biol. Chem. 8: 8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vitaterna M.H., Selby, C.P., Todo, T., Niwa, H., Thompson, C., Fruechte, E.M., Hitomi, K., Thresher, R.J., Ishikawa, T., Miyazaki, J., et al. 1999. Differential regulation of mammalian period genes and circadian rhythmicity by cryptochromes 1 and 2. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 96: 12114–12119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Gall C., Duffield, G.E., Hastings, M.H., Kopp, M.D., Dehghani, F., Korf, H.W., and Stehle, J.H. 1998. CREB in the mouse SCN: A molecular interface coding the phase-adjusting stimuli light, glutamate, PACAP, and melatonin for clockwork access. J. Neurosci. 18: 10389–10397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinert H., Weinert, D., Schurov, I., Maywood, E.S., and Hastings, M.H. 2001. Impaired expression of the mPer2 circadian clock gene in the suprachiasmatic nuclei of aging mice. Chronobiol. Int. 18: 559–565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yagita K., Yamaguchi, S., Tamanini, F., van der Horst, G.T., Hoeijmakers, J.H., Yasui, A., Loros, J.J., Dunlap, J.C., and Okamura, H. 2000. Dimerization and nuclear entry of mPER proteins in mammalian cells. Genes & Dev. 14: 1353–1363. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yagita K., Tamanini, F., van der Horst, G.T.J., and Okamura, H. 2001. Molecular mechanism of the biological clock in cultured fibroblasts. Science 292: 278–281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yagita K., Tamanini, F., Yasuda, M., Hoeijmakers, J.H., van der Horst, G.T., and Okamura, H. 2002. Nucleocytoplasmic shuttling and mCRY-dependent inhibition of ubiquitylation of the mPER2 clock protein. EMBO J. 21: 1301–1314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamazaki S., Numano, R., Abe, M., Hida, A., Takahashi, R., Ueda, M., Block, G.D., Sakaki, Y., Menaker, M., and Tei, H. 2000. Resetting centraland peripheral circadian oscillators in transgenic rats. Science 288: 682–685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamazaki S., Straume, M., Tei, H., Sakaki, Y., Menaker, M., and Block, G.D. 2002. Effects of aging on central and peripheral mammalian clocks. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 99: 10801–10806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan L. and Okamura, H. 2002. Gradients in the circadian expression of Per1 and Per2 genes in the rat suprachiasmatic nucleus. Eur. J. Neurosci. 15: 1153–1162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu W., Nomura, M., and Ikeda, M. 2002. Interactivating feedback loops within the mammalian clock: BMAL1 is negatively autoregulated and upregulated by CRY1, CRY2, and PER2. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 290: 933–941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng B., Larkin, D.W., Albrecht, U., Sun, Z.S., Sage, M., Eichele, G., Lee, C.C., and Bradley, A. 1999. The mPer2 gene encodes a functional component of the mammalian circadian clock. Nature 400: 169–173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng B., Albrecht, U., Kaasik, K., Sage, M., Lu, W., Vaishnav, S., Li, Q., Sun, Z.S., Eichele, G., Bradley, A., et al. 2001. Nonredundant roles of the mPer1 and mPer2 genes in the mammalian circadian clock. Cell 105: 683–694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zylka M.J., Shearman, L.P., Weaver, D.R., and Reppert, S.M. 1998. Three period homologs in mammals: Differential light responses in the suprachiasmatic circadian clock and oscillating transcripts outside of brain. Neuron 20: 1103–1110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]