Abstract

To understand the role of chromatin-remodeling activities in transcription, it is necessary to understand how they interact with transcriptional activators in vivo to regulate the different steps of transcription. Human heat shock factor 1 (HSF1) stimulates both transcriptional initiation and elongation. We replaced mouse HSF1 in fibroblasts with wild-type and mutant human HSF1 constructs and characterized regulation of an endogenous mouse hsp70 gene. A mutation that diminished transcriptional initiation led to twofold reductions in hsp70 mRNA induction and recruitment of a SWI/SNF remodeling complex. In contrast, a mutation that diminished transcriptional elongation abolished induction of full-length mRNA, SWI/SNF recruitment, and chromatin remodeling, but minimally impaired initiation from the hsp70 promoter. Another remodeling factor, SNF2h, is constitutively present at the promoter irrespective of the genotype of HSF1. These data suggest that localized recruitment of SWI/SNF drives a specialized remodeling reaction necessary for the production of full-length hsp70 mRNA.

Keywords: hsp70, SWI/SNF, heat shock, chromatin, transcription, elongation

Transcriptional activators regulate gene expression by a variety of mechanisms. They stimulate many steps in the process of transcription, including formation of the preinitiation complex, promoter opening, initiation, promoter clearance, and elongation. Activators direct these events through interactions with the basal transcription machinery, general transcription factors, and chromatin-remodeling factors. Chromatin-remodeling activities can be divided into two broad categories: those that use the energy of ATP to change the association of DNA with core histones and those that alter DNA–histone interactions through covalent modifications of histone tails. Both activities are involved in transcriptional regulation, and mammalian cells contain several complexes of each kind (for review, see Becker and Horz 2002; Berger 2002). Transcriptional activators can target both histone tail-modification complexes and ATP-dependent remodeling complexes (Utley et al. 1998; Yudkovsky et al. 1999; for review, see Narlikar et al. 2002).

Mammalian cells contain a variety of ATP-dependent chromatin-remodeling complexes that appear to play a role in regulating several key nuclear processes. The three major families of ATP-dependent remodeling complexes are characterized by their ATPase subunits: SWI/SNF, ISWI, and Mi-2. Whereas SWI/SNF and ISWI family complexes function in both transcriptional activation and repression, the Mi-2 family appears to function solely in repression (for review, see Narlikar et al. 2002). Mammalian SWI/SNF is an ∼2-MD complex consisting of either the BRM or BRG1 ATPase and several additional subunits, whereas the mammalian ISWI homolog SNF2h participates in several chromatographically distinct complexes. SNF2h, hBRG1, and hBRM can all remodel chromatin in the absence of the other subunits (Corona et al. 1999; Phelan et al. 1999; Aalfs et al. 2001). The primary mechanism by which SNF2h remodels chromatin is translational repositioning of the histone octamer along the DNA (Hamiche et al. 1999; Langst et al. 1999); BRG1 appears to differ from SNF2h in substrate requirements and in the products that are created by remodeling (Whitehouse et al. 1999; Narlikar et al. 2001; Fan et al. 2003).

Human heat shock factor 1 (HSF1) has been shown to interact with SWI/SNF and to stimulate both transcriptional initiation and release of an RNA polymerase paused near the promoter of the 70-kD heat shock protein (hsp70) gene. In vitro, formation of a stably paused polymerase complex requires assembly of the template into nucleosomes (Brown et al. 1996); specific phenylalanine residues in the HSF1 activation domains were required to stimulate release of this paused polymerase (Brown et al. 1998). In contrast, mutations in acidic residues of the HSF1 activation domains impair transcriptional initiation but not elongation. Although mutation of these acidic residues decreases interaction between HSF1 and SWI/SNF in cell-free extracts, mutation of the phenylalanine residues completely abolishes the HSF1–SWI/SNF interaction (Sullivan et al. 2001). Thus, remodeling of the nucleosomes immediately adjacent to the pause might be an important component of hsp70 activation. Recruitment of a chromatin-remodeling complex is unlikely to be the sole mechanism by which HSF1 stimulates release of the paused polymerase. In Drosophila, where pausing of RNA polymerase on the hsp70 promoter was discovered (Gilmour and Lis 1986; Rougvie and Lis 1988), recruitment of the Pol II CTD kinase pTEFb to the promoter is sufficient to stimulate transcriptional elongation (Lis et al. 2000). Furthermore, immunofluorescence of polytene chromosomes did not detect recruitment of the Drosophila SWI/SNF complex to hsp70 (Armstrong et al. 2002). However, the stability of the paused polymerase in Drosophila appears to be more closely linked to interactions with promoter-bound factors than to the structure of the template (Benjamin and Gilmour 1998; Tang et al. 2000). The ability of human HSF1 to target SWI/SNF, in addition to the requirement for nucleosomes in order to form a stable pause at the human hsp70 promoter, suggest a greater role for chromatin structure in the regulation of the mammalian hsp70 gene.

To investigate the role that chromatin remodeling plays in activation of elongation on the mammalian hsp70 promoter, we have identified specific regions of HSF1 that recruit remodeling factors to an endogenous hsp70 gene. Immortalized fibroblasts from an Hsf1-/- mouse were used to make stable cell lines that express wild-type HSF1 and HSF1 with point mutations in either key acidic residues or key phenylalanine residues. In these cell lines, HSF1 is required for stress tolerance, hsp70 mRNA induction, and heat-induced SWI/SNF recruitment and chromatin remodeling on the hsp70 gene. Phenylalanine-mutant hHSF1 does not confer stress tolerance, hsp70 induction, remodeling, or SWI/SNF recruitment. However, this mutant directs polymerase initiation on the hsp70 promoter to the same degree as wild-type HSF1, implying that the specific defect of this mutant in vivo is in efficient stimulation of elongation. In contrast to SWI/SNF, an ISWI-related complex is constitutively present at the promoter irrespective of HSF1 genotype. Thus, specific and localized recruitment of SWI/SNF to the hsp70 gene occurs concurrently with localized chromatin remodeling and stimulation of elongation.

Results

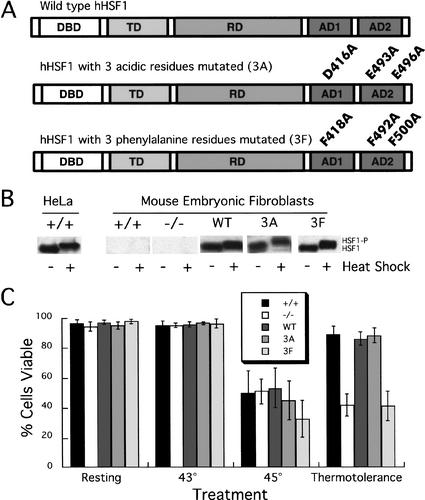

Mouse cell lines that express wild-type and mutant human HSF1

To identify the effects of HSF1 activation domain mutations on hsp70 induction in a native chromatin context, stable cell lines were constructed that express either wild-type or mutant human HSF1 as the sole inducible heat-shock factor in the cell. Full-length wild-type and mutant hHSF1 proteins were expressed using the pBABE retroviral vector (Land 1990). In each mutant construct, three critical activation domain residues were mutated to alanine: residues D416, E493, and E496 in the acidic mutant and residues F418, F492, and F500 in the phenylalanine mutant (Fig. 1A). These residues had previously been identified as being important to HSF1 activation via transfection and in vitro transcription studies (Newton et al. 1996; Brown et al. 1998).

Figure 1.

Wild-type and mutant human HSF1 are functional when stably expressed in mouse Hsf1-/- fibroblasts. (A) Schematic of wild-type and mutant human HSF1 constructs showing the DNA-binding domain (DBD), trimerization domain (TD), regulatory domain (RD), and activation domains (AD1 and AD2) of HSF1. (B) Mobility of wild-type and mutant versions of human HSF1. Nuclear extracts from resting and heat-shocked cells were resolved by SDS-PAGE and probed with a polyclonal antibody specific for human HSF1; the mobility shift (HSF1-P) has previously been shown to be caused by phosphorylation. (C) Wild-type and 3A hHSF1 restore thermotolerance to Hsf1-/- cells; 3F hHSF1 does not. The percentage of viable cells was determined by treating cells with Trypan Blue immediately following exposure to different temperature conditions. Standard errors are indicated (n > 3).

The recombinant retroviruses were used to infect immortalized embryonic fibroblasts from an Hsf1-/- mouse (McMillan et al. 1998; Luft et al. 2001). Several clonal cell lines expressing each construct were isolated; those chosen for further study expressed the transgenic construct at approximately the same level as HeLa cells express endogenous human HSF1 as judged by Western analysis (Fig. 1B; data not shown). Following heat shock, the mobility of the transgenic proteins decreases as expected because of hyperphosphorylation (Fig. 1B). The transgenic cell lines will be referred to as WT (expresses wild-type human HSF1), 3A (expresses the acidic-mutant construct), and 3F (expresses the phenylalanine-mutant construct). The mouse Hsf1+/+ cell line used here was immortalized in the same manner as Hsf1-/- fibroblasts from mice of the same genetic background with an intact HSF1 gene (McMillan et al. 1998). These cell lines allowed us to study the effects of point mutations in the HSF1 activation domains on expression of the endogenous hsp70 promoter in otherwise identical genetic backgrounds.

To verify that human HSF1 restored a wild-type phenotype to Hsf1-/- mouse fibroblasts, and to determine whether the activation domain point mutations impaired HSF1 function in vivo, we characterized thermotolerance and hsp70 transcriptional induction in the transgenic cell lines. Immediately following a naive exposure to a severe heat shock (45°C), only 58% of mouse Hsf1+/+ fibroblasts were viable. However, when these cells were preconditioned by exposure to a 43°C shock followed by a resting period at 37°C, 89% of the cells were viable (Fig. 1C). Mouse Hsf1-/- cells did not develop thermotolerance. Both WT and 3A hHSF1 are able to confer thermotolerance to Hsf1-/- fibroblasts, but 3F hHSF1 is not. Thus, as previously reported (McMillan et al. 1998), Hsf1-/- cells have a defect in thermotolerance rather than in immediate survival of heat stress. Mutation of phenylalanine residues seriously impairs in vivo HSF1 function, as this construct does not restore thermotolerance.

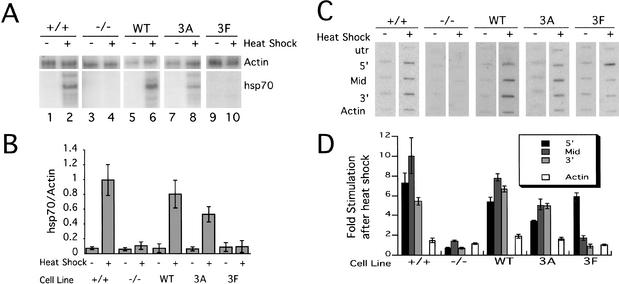

The development of thermotolerance requires an intact heat-shock response including the production of HSP70 protein. Mild heat shock induces hsp70 transcription in wild-type cells but not in Hsf1-/- fibroblasts (McMillan et al. 1998). We used S1 analysis to examine steady-state hsp70 mRNA levels under normal growth conditions and during heat shock. Both WT and 3A hHSF1 stimulated hsp70 mRNA induction following heat shock, but 3F hHSF1 did not (Fig. 2A, lanes 5–10, 2B). The ∼50% impairment of hsp70 induction by the 3A construct was consistently observed in a variety of assays (see below). The inability of the phenylalanine mutant to activate the hsp70 promoter is consistent with its phenotype in the thermotolerance assay.

Figure 2.

Expression of wild-type or acidic-mutant hHSF1 restores hsp70 mRNA induction; expression of phenylalanine-mutant hHSF1 does not. (A) S1 analysis of the total level of hsp70 mRNA following heat shock. (B) Quantitation of S1 analysis normalized to signal from the actin probe. Standard errors are indicated (n = 3). (C) Nuclear run-on analysis. RNA was hybridized to four probes across the hsp70 gene and one probe to the mouse skeletal β-actin gene. (D) Quantitation of nuclear run-on data (n = 3). For each cell line, the fold increase in signal following heat shock for each probe is presented, corrected for background signal from the UTR probe as well as from the filters themselves, and is normalized to the number of uridines in each probe.

Mutation of phenylalanine residues impairs transcript elongation in vivo

The differential effects of mutations of acidic and phenylalanine residues on transactivation were originally observed as a difference in the ratio of abortive to full-length transcripts in an in vitro transcription assay on chromatinized templates. Acidic-mutant hHSF1 activation domains stimulated a low level of both abortive and full-length transcripts, whereas the phenylalanine mutant directed production of high levels of abortive, paused transcript but very little full-length transcript (Brown et al. 1998). To characterize the phenotypes of these mutations in vivo, nuclear run-on analysis was used to determine the location and density of engaged RNA polymerases during heat shock. Labeled mRNA produced in isolated nuclei was hybridized to filters with four probes to different regions of the mouse hsp70 gene and one probe to the mouse skeletal β-actin gene (Fig. 2C,D). In Hsf1+/+ fibroblasts, heat shock induced increased polymerase density across the entire hsp70 gene (Fig. 2C,D), whereas Hsf1-/- fibroblasts show no substantial increase in polymerase density on any portion of the gene. Expression of wild-type hHSF1 restored increased polymerase density to nearly the same levels as mouse fibroblasts expressing endogenous HSF1. 3A and 3F hHSF1 produced different patterns of polymerase density following heat-shock induction. Cells expressing 3A hHSF1 showed moderately increased density across the gene, whereas 3F directed significantly increased density only at the 5′ probe (sixfold), compared with the mid-probe (twofold) or the 3′ probe (no stimulation). Although the acidic mutant impairs initiation to approximately the same extent that it impairs transcript accumulation in vivo, the phenylalanine mutant does not impair initiation but does cause a significant decrease in the ability of RNA polymerase to elongate corresponding to the significant decrease in transcript accumulation in 3F cells (Fig. 2, cf. B and D). These two sets of mutations disrupt specific portions of the process of transcriptional activation.

Heat-inducible chromatin remodeling of the hsp70 gene requires phenylalanine residues of HSF1

Previous work suggests that the ability of HSF1 to stimulate transcriptional elongation might be directly linked to its ability to direct chromatin remodeling. In vitro, HSF1 stimulates elongation only on DNA templates that have been assembled into nucleosomes (Brown et al. 1996). Mutations in phenylalanine residues do not impair transcriptional activation on naked DNA templates, but acidic residue mutations decrease activation on both assembled and naked templates (Brown et al. 1998). Furthermore, wild-type HSF1 coimmunoprecipitates with BRG1 and targets SWI/SNF-remodeling activity in vitro, but phenylalanine-mutant HSF1 is defective in both of these activities (Sullivan et al. 2001). We therefore reasoned that HSF1 might recruit SWI/SNF to remodel the hsp70 promoter through phenylalanine residues of the activation domains and that this recruitment is required for transcript elongation.

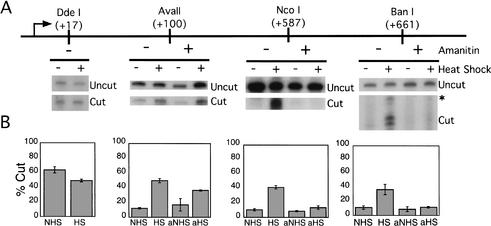

We used a restriction enzyme accessibility assay to measure chromatin remodeling on the hsp70 gene in response to heat-shock induction. Nucleosomal DNA is normally refractory to cleavage by restriction enzymes, but chromatin remodeling significantly increases restriction enzyme access. To assay the chromatin structure of the hsp70 gene, nuclei were isolated from heat-shocked and resting cells and incubated with restriction enzymes that cut at discrete sites along the hsp70 gene. The digested DNA was isolated, deproteinated, and digested with a second, reference enzyme. Cutting was visualized by ligation-mediated PCR (LMPCR). In Figures 3 and 4, the band produced by the in vivo enzyme is referred to as “cut” and the band produced by the reference enzyme is “uncut.” In Hsf1+/+ fibroblasts, as previously seen with human cells, most of the hsp70 gene is refractory to restriction enzyme digestion under normal growth conditions, and accessibility increases following heat shock, although a site between the transcriptional start site and the paused polymerase (DdeI at +17) was accessible in both resting and heat-shocked cells (Fig. 3A).

Figure 3.

The chromatin structure of the hsp70 gene is altered following heat shock induction. (A) Restriction enzyme accessibility. Nuclei were harvested from Hsf1+/+ cells under normal growth conditions, following treatment with α-amanitin for 1 h, following incubation at 43°C for 1 h, or after treatment with amanitin followed by heat shock. Harvested nuclei were digested with one of the indicated enzymes (cut), and DNA was isolated and digested with a second, reference enzyme (uncut). BanI cleavage produced a set of bands 63–67 bp in size, most likely because of heterogeneity introduced during LMPCR. (B) Quantification from at least two independent preparations of nuclei are expressed as percentage of the signal from the in vivo restriction enzyme site relative to the total signal in each lane.

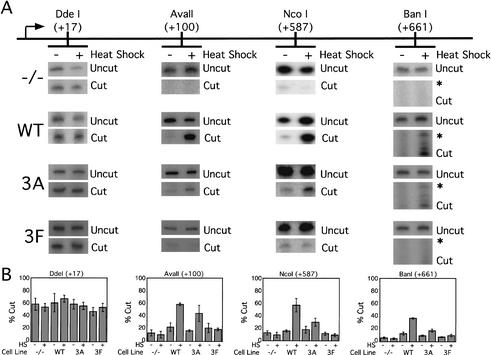

Figure 4.

Heat-shock-induced chromatin remodeling depends on HSF1 activation domains. Nuclei were harvested from Hsf1-/-, 3A, and 3F cells under normal growth conditions or following incubation at 43°C for 1 h. Restriction enzyme accessibility was assayed and quantitated as in Figure 3 from three independent preparations of nuclei.

In addition to remodeling by ATP-dependent complexes, chromatin structure can also be disrupted by polymerase movement. To determine the dependence of heat-induced accessibility on polymerase movement, cells were incubated prior to heat shock with the Pol II inhibitor α-amanitin at a concentration sufficient to eliminate hsp70 transcription (data not shown). Accessibility of the AvaII site at +100 increased approximately fourfold following heat shock; treatment with α-amanitin did not decrease the level of heat-shock-induced remodeling at this site. In contrast, heat-shock-induced restriction enzyme accessibility of the NcoI (+587) and BanI (+661) sites was sensitive to α-amanitin (Fig. 3A, right panels). We conclude that the mouse hsp70 gene is remodeled during heat-shock induction. Close to the promoter, remodeling is independent of transcription, but farther downstream, polymerase movement is required for chromatin remodeling.

To determine the role that HSF1 plays in directing chromatin remodeling, restriction enzyme accessibility was assayed in Hsf1-/-, WT, 3A, and 3F cells. Heat-shock-inducible chromatin remodeling required HSF1; no increase in accessibility was observed following heat shock in Hsf1-/- cells (Fig. 4, -/- panels). Expression of wild-type hHSF1 restored inducible remodeling to the same level as that observed in Hsf1+/+ cells (Fig. 4, WT panels). Expression of 3A hHSF1 restored some chromatin remodeling, but not to the same degree as wild-type human or mouse HSF1. As in the nuclear run-on and S1 nuclease analyses, the acidic mutations impaired remodeling ∼50% relative to WT. In contrast, 3F hHSF1 did not restore any inducible remodeling; the accessibility pattern in 3F cell lines is similar to that in the -/- cell line (Fig. 4, cf. -/- and 3F panels). The DdeI site at +17 was accessible under both resting and heat-shocked conditions in all cell lines; accessibility of this site serves as a control for the ability of nuclei from each cell line to be digested efficiently. We conclude that HSF1 is required for heat-shock-induced chromatin remodeling on the hsp70 gene and that remodeling is directed via phenylalanine residues of the activation domains as is stimulation of elongation.

BRG1 and SNF2h behave differently at the hsp70 promoter

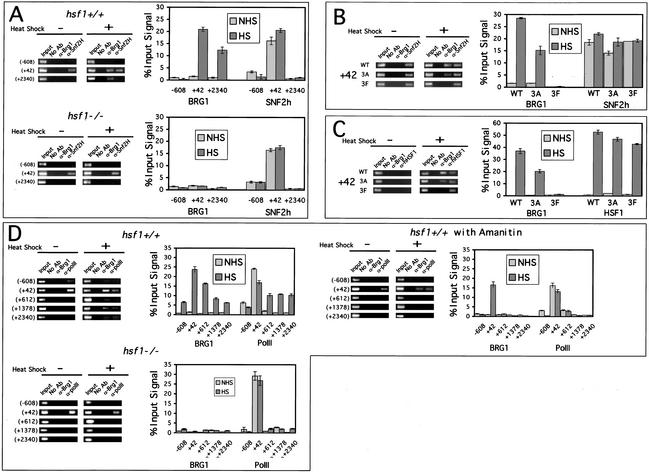

Mammalian cells contain several different ATP-dependent chromatin-remodeling activities. In vitro, these complexes create different remodeled structures that may indicate different in vivo functions. To determine if either SWI/SNF or ISWI-related complexes are recruited to the hsp70 promoter following heat shock in vivo, chromatin immunoprecipitations were carried out from Hsf1-/- and Hsf1+/+ cells using anti-BRG1 and anti-SNF2h antibodies and PCR primers centered on -608, +42, and +2340 relative to the start of hsp70 transcription. SNF2h was present at the hsp70 promoter in both resting and heat-shocked cells regardless of the presence or absence of HSF1, but BRG1 was recruited following heat shock in Hsf1+/+ cells but not Hsf1-/- cells (Fig. 5A). SNF2h was detected only at the promoter, whereas BRG1 was also associated with downstream regions of the gene.

Figure 5.

SNF2h is present at the hsp70 promoter in resting cells, whereas SWI/SNF is recruited to the promoter following heat shock and associates with downstream chromatin in a polymerase-dependent manner. (A) Chromatin immunoprecipitations (ChIPs) were carried out with an anti-BRG1 antibody, an anti-SNF2h antibody, or no antibody and PCR primers that centered on -608, +42, or +2340 relative to the start of transcription (n = 3). All reactions in this figure contain 0.5% of the input material and 2.5% of the no-antibody or antibody samples recovered. (B) BRG1 recruitment in Hsf1-/- cells is rescued by WT or 3A hHSF1. ChIPs were carried out using an anti-BRG1 antibody, an anti-SNF2h antibody, or no antibody, and isolated DNA samples were amplified using primers that centered on +42 (n = 3). (C) HSF1 is recruited to the hsp70 promoter of all three transgenic cell lines following heat shock. ChIPs were carried out using an anti-BRG1 antibody, an anti-HSF1 antibody, or no antibody, and isolated DNA samples were amplified using primers that centered on +42 (n = 3). (D) BRG1 association with downstream chromatin following heat shock depends on polymerase movement. ChIPs were carried out on resting and heat-shocked Hsf1-/- (n = 2) and Hsf1+/+ cells (n = 4), and Hsf1+/+ cells that had been treated with α-amanitin (n = 3) using an anti-BRG1 antibody, an anti-PolII antibody, or no antibody, and isolated DNA samples were amplified using primers that centered on -608, +42, +612, +1378, and +2340 relative to the start of transcription.

BRG1 recruitment is dependent on an intact heat-shock response. BRG1 was recruited to the hsp70 promoter in cell lines expressing either WT or 3A hHSF1, but 3A hHSF1 recruited BRG1 to the hsp70 promoter at ∼50% of the wild-type level, echoing its level of impairment in transcription and chromatin remodeling (Fig. 5B). BRG1 was not recruited to the promoter in Hsf1-/- cells or in cells expressing 3F hHSF1. We conclude that although some mechanism other than HSF1 brings SNF2h to the hsp70 promoter under normal growth conditions, HSF1 specifically recruits BRG1 in response to heat shock via the phenylalanine residues of its activation domains.

It is possible that the phenotypes observed in the mutant cell lines result from failure of human HSF1 to interact with the mouse hsp70 gene. To verify that the transgenic proteins bind to the hsp70 promoter following heat shock, chromatin immunoprecipitations were carried out using an antibody specific for human HSF1. Following heat shock, hHSF1 is detected at the hsp70 promoter in all three transgenic cell lines (Fig. 5C). As in Figure 5A, the presence or absence of BRG1 was dictated by the activation domain; the 3F mutant did not recruit BRG1. Therefore, the phenotypes observed in the 3A and 3F cell lines result from inability of the proteins to activate transcription, not from their absence from the promoter.

BRG1 and Pol II move into the hsp70 gene following heat shock

Although several transcription factors have been shown to recruit SWI/SNF to promoters, it is less clear if remodeling activity is required for transcriptional elongation through the coding regions of genes. To determine if BRG1 is associated with downstream regions of the hsp70 gene and if that association requires polymerase movement, chromatin immunoprecipitations using antibodies to BRG1 and the largest subunit of Pol II were carried out followed by PCR with a series of primers throughout the coding region of the hsp70 gene. In both Hsf1-/- and Hsf1+/+ fibroblasts, Pol II was associated with the hsp70 promoter under normal growth conditions, but not with the coding region of the gene (Fig. 5D). In Hsf1+/+ cells, both polymerase and BRG1 were associated with downstream regions of the gene following heat shock, but their patterns of association were different. The level of BRG1 association decreased through the gene, whereas the level of polymerase association remained constant away from the promoter. Neither polymerase nor BRG1 were detected downstream following heat shock in Hsf1-/- cells. α-Amanitin treatment of cells prior to heat shock did not impair recruitment of BRG1 to the hsp70 promoter, nor did this pretreatment disrupt the association of polymerase with the promoter. However, in the presence of amanitin, neither Pol II nor BRG1 was found downstream of the promoter. Thus, BRG1 is recruited in a highly localized fashion following heat shock, and association of BRG1 with downstream regions of the gene depends on RNA polymerase movement.

Discussion

It is well established that several transcriptional activators can interact directly with SWI/SNF-family remodeling complexes and target those activities, although the roles that these targeting interactions play in regulating gene expression are not well understood. The work described here suggests a specific mechanistic role for recruitment of SWI/SNF by HSF1: the remodeling of nucleosomes in front of the paused polymerase to facilitate release of the pause.

In cells under normal growth conditions, the hsp70 promoter is clear of nucleosomes and contains not only a transcriptionally engaged polymerase, but also a SNF2h-containing ISWI-related remodeling complex. In vitro, SNF2h remodels nucleosomes by translationally repositioning the histone octamer relative to the DNA, and it is possible that SNF2h maintains the open chromatin structure of the unstressed hsp70 promoter in vivo using a similar mechanism. However, SNF2h activity is apparently insufficient to allow productive transcription, which we propose requires SWI/SNF-dependent nucleosome remodeling downstream of the paused polymerase; the abilities of HSF1 to recruit BRG1 and to remodel downstream chromatin structure are correlated. In contrast, SNF2h was present at the hsp70 promoter regardless of the presence or genotype of HSF1, but did not become associated with downstream regions following heat shock, suggesting that it does not play a key role in elongation.

Following heat shock, BRG1 is not only recruited to the hsp70 promoter, but is also associated with downstream regions of the gene. It is not clear how BRG1 moves through the gene; unlike polymerase, SWI/SNF activity is not directional in vitro. It is possible that SWI/ SNF associates directly with the elongating polymerase because inhibition of polymerase movement restricts BRG1 association and chromatin remodeling to the region immediately downstream of the paused polymerase. However, although some preparations of polymerase contain SWI/SNF (Wilson et al. 1996; Neish et al. 1998), it is not a stoichiometric component of polymerase, and no direct interactions between SWI/SNF and polymerase subunits have been described. Furthermore, the ratio of polymerase signal to BRG1 signal increases farther from the promoter, indicating that SWI/SNF associates with the gene somewhat independently of Pol II. It is possible that SWI/SNF relies on polymerase to promote its association with transcribed chromatin through a HAT activity associated with the elongating polymerase. SWI/SNF binds more strongly to nucleosomes with acetylated histone tails and preferentially remodels these nucleosomes (Hassan et al. 2001, 2002). Furthermore, many SWI/SNF promoters have been shown to require histone acetylation prior to SWI/SNF binding both in vitro (Agalioti et al. 2000; Dilworth et al. 2000) and in vivo (Reinke et al. 2001; Soutoglou and Talianidis 2002). An elongating polymerase associated with a HAT activity could confer directionality on SWI/SNF by generating acetylated nucleosomes as it passed through the gene.

In addition to mediating localized recruitment of SWI/SNF, HSF1 may also effect changes in the transcription machinery. Drosophila HSF recruits the Pol II CTD kinase pTEFb and the elongation factor Spt6 to the hsp70 locus in response to heat shock (Andrulis et al. 2000; Lis et al. 2000). It is possible that mammalian HSF1 recruits homologs of these proteins in addition to SWI/SNF, although not all attributes of the heat-shock response are evolutionarily conserved. Drosophila BRM was not localized to the induced hsp70 gene in immunofluoresence studies on polytene chromosomes, although highly localized recruitment as seen here might not be visible with this protocol.

These experiments highlight the complexity of transcriptional activation domain function. The phenylalanine residues that are required for efficient stimulation of elongation and recruitment of BRG1 are interspersed with the acidic residues of HSF1 that are required for maximal stimulation of initiation. No structural information exists for the activation domains of HSF1. These two sets of residues might form discrete interaction surfaces, but the same regions of the HSF1 activation domains must play more than one role in vivo to stimulate transcription and presumably must interact with complexes other than SWI/SNF to promote activation.

Materials and methods

Cell line construction and viability assay

Wild-type and mutant full-length human HSF1 constructs were subcloned into the pBABE-PURO retroviral expression vector (Land 1990), these constructs were transfected into the BING packaging cell line (Ausubel et al. 1996), and supernatants were used to infect mouse Hsf1-/- embryonic fibroblasts (McMillan et al. 1998). Following colony selection under 5 μg/mL puromycin, resistant cell lines were screened for hHSF1 expression by blotting nuclear extract from resting and heat-shocked (43°C for 1 h) cells with an antibody against human HSF1 (Stressgen). Cell lines that expressed hHSF1 at approximately the same level as the endogenous gene in HeLa cells were expanded and carried in 1× DMEM with 15% fetal bovine serum and 1 μg/mL puromycin. HSF1 levels were monitored throughout the course of experimentation. Cells were tested for viability immediately following various heat-shock treatments as described in McMillan et al. (1998). In all subsequent experiments, cells identified as heat shocked were incubated at 43°C for 1 h.

S1 nuclease assay

RNA was isolated from heat-shocked and resting cells using the QIAGEN RNeasy RNA isolation kit. The RNA was resuspended in TE and 5 or 10 μg was incubated with 0.2 pmole of each radiolabeled gel-purified probe at 55°C for 2 h in 1× S1 hybridization buffer (3 M NaCl, 0.5 M HEPES at pH 7.5, and 1 mM EDTA at pH 8.0). The actin probe corresponded to -5 through +60 relative to the start of transcription of the mouse skeletal β-actin gene. The hsp70 probe corresponded to -5 through +50 of the mouse hsp70A1 gene. Each probe contained 5 bases of random sequence on its 5′ end. Following extractions with phenol and chloroform and ethanol precipitation, the reactions were resuspended in 1× S1 nuclease buffer (GIBCO). Then 26 units of S1 nuclease was added to each reaction, which was incubated at 37°C for 1 h. Reactions were analyzed using 20% polyacrylamide-urea gels and quantitated using a Molecular Dynamics PhosphorImager.

Nuclear run-ons

Probes were generated by PCR using primers corresponding to the following regions of the mouse hsp70A1 gene relative to the start of transcription: 5′-UTR (-166 to -28); 5′ (+8 to +160); mid (+526 to +698); 3′ (+1187 to +1567); mouse skeletal β-actin gene, actin (+614 to +843). Nuclei were prepared from resting and heat-shocked cells, and nuclear run-on reactions were carried out as described (Brown and Kingston 1997) in low-salt conditions in the absence of sarkosyl. RNA harvesting was performed according to the procedure described in Schübeler (1997). Blots were quantitated by PhosphorImager.

In vivo restriction enzyme accessibility assay

Amanitin-treated cells were incubated with 50 μg/mL α-amanitin (Roche) for 1 h prior to heat shock. Nuclei were prepared as for nuclear run-ons. In vivo restriction enzyme accessibility assays were carried out as described in Brown (1997). The primers used to detect cleavages at +17 and +100 on the mouse hsp70A1 gene corresponded to the following regions relative to the start of transcription: -166 to -145, -85 to -66, and -72 to -52. The primers used to detect cleavages at +587 and +661 corresponded to +745 to +722, +703 to +683, and +699 to +677.

Chromatin immunoprecipitation

Resting and heat-shocked cells were cross-linked for 5 min in 0.37% formaldehyde at 37°C or 43°C, respectively. The cells were washed twice with 1× PBS and trypsinized. Nuclei were prepared as described for the nuclear run-on assay, resuspended in 200 μL of 1× Micrococcal Nuclease Buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl at pH 7.4, 10 mM NaCl, 3 mM MgCl2, 1 mM CaCl2, 4% NP-40, 1 mM PMSF), and incubated with 6 units of Micrococcal Nuclease (at 1 U/μL in 5 mM sodium phosphate at pH 7.0, 2.5 mM CaCl2) at 37°C for 6 min. The reactions were stopped with 6 μL of 100 mM EGTA and 1 mL of ChIP Lysis Buffer (1% NP-40, 10 mM EDTA at pH 8.0, 50 mM Tris-HCl at pH 8.0; DiRenzo et al. 2000). Each sample was sonicated using a Heat Systems W-375 sonicator for a total of 2 min in 30-sec bursts at 50% duty cycle and power setting 3 and then centrifuged for 2 min at 8000 rpm. Agarose gel electrophoresis showed that the products of this treatment were evenly divided between mono-, di-, tri-, and quatro-nucleosomes.

Immunoprecipitations were carried out as described in DiRenzo et al. (2000). Antibodies against BRG1 (Sif et al. 1998), SNF2h (Aalfs et al. 2001), and hHSF1 (Stressgen) were used at a dilution of 1:100; the anti-Pol II antibody (Santa Cruz) was used at 1:50. Following 25 cycles of PCR (92°C for 30 sec, 58°C for 30 sec, and 72°C for 1 min), the samples were run on 2% agarose gels, visualized with ethidium bromide, and quantitated by densitometry. Five pairs of primers to the mouse hsp70A1 gene were used to produce products centered at different points relative to the start of transcription: -608 (-674 to -655 and -542 to -519), +42 (-85 to -66 and +168 to +153), +612 (+526 to +548 and +698 to +680), +1378 (+1189 to +1203), and +2340 (+2247 to +2266 and +2412 to +2432).

Acknowledgments

We thank J. Dennis, R. Dunn, N. Francis, I. King, and G. Narlikar for comments on the manuscript. This work was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health and Hoescht AG to R.E.K.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by payment of page charges. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

Corresponding author.

Article and publication are at http://www.genesdev.org/cgi/doi/10.1101/gad.1071803.

References

- Aalfs J.D., Narlikar, G.J., and Kingston, R.E. 2001. Functional differences between the human ATP-dependent nucleosome remodeling proteins BRG1 and SNF2H. J. Biol. Chem. 276: 34270–34278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agalioti T., Lomvardas, S., Parekh, B., Yie, J., Maniatis, T., and Thanos, D. 2000. Ordered recruitment of chromatin modifying and general transcription factors to the IFN-β promoter. Cell 103: 667–678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrulis E.D., Guzman, E., Doring, P., Werner, J., and Lis, J.T. 2000. High-resolution localization of Drosophila Spt5 and Spt6 at heat shock genes in vivo: Roles in promoter proximal pausing and transcription elongation. Genes & Dev. 14: 2635–2649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armstrong J.A., Papoulas, O., Daubresse, G., Sperling, A.S., Lis, J.T., Scott, M.P., and Tamkun, J.W. 2002. The Drosophila BRM complex facilitates global transcription by RNA polymerase II. EMBO J. 21: 5245–5254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ausubel F.M., Brent, R., Kingston, R.E., Moore, D.D., Seidman, J.G., Smith, J.A., and Struhl, K. 1996. Current protocols in molecular biology. John Wiley and Sons, New York.

- Becker P.B. and Horz, W. 2002. ATP-dependent nucleosome remodeling. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 71: 247–273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benjamin L.R. and Gilmour, D.S. 1998. Nucleosomes are not necessary for promoter-proximal pausing in vitro on the Drosophila hsp70 promoter. Nucleic Acids Res. 26: 1051–1055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berger S.L. 2002. Histone modifications in transcriptional regulation. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 12: 142–148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown S.A. 1997. “Roles for activators and chromatin in the regulation of transcriptional elongation.” Ph.D thesis, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA.

- Brown S.A. and Kingston, R.E. 1997. Disruption of downstream chromatin directed by a transcriptional activator. Genes & Dev. 11: 3116–3121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown S.A., Imbalzano, A.N., and Kingston, R.E. 1996. Activator-dependent regulation of transcriptional pausing on nucleosomal templates. Genes & Dev. 10: 1479–1490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown S.A., Weirich, C.S., Newton, E.M., and Kingston, R.E. 1998. Transcriptional activation domains stimulate initiation and elongation at different times and via different residues. EMBO J. 17: 3146–3154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corona D.F., Langst, G., Clapier, C.R., Bonte, E.J., Ferrari, S., Tamkun, J.W., and Becker, P.B. 1999. ISWI is an ATP-dependent nucleosome remodeling factor. Mol. Cell 3: 239–245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dilworth F.J., Fromental-Ramain, C., Yamamoto, K., and Chambon, P. 2000. ATP-driven chromatin remodeling activity and histone acetyltransferases act sequentially during transactivation by RAR/RXR in vitro. Mol. Cell 6: 1049–1058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiRenzo J., Shang, Y., Phelan, M., Sif, S., Myers, M., Kingston, R., and Brown, M. 2000. BRG-1 is recruited to estrogen-responsive promoters and cooperates with factors involved in histone acetylation. Mol. Cell. Biol. 20: 7541–7549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan H.-Y., He, X., Kingston, R., and Narlikar, G. 2003. Distinct strategies to make nucleosomal DNA accessible. Mol. Cell (in press). [DOI] [PubMed]

- Gilmour D.S. and Lis, J.T. 1986. RNA polymerase II interacts with the promoter region of the noninduced hsp70 gene in Drosophila melanogaster cells. Mol. Cell. Biol. 6: 3984–3989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamiche A., Sandaltzopoulos, R., Gdula, D.A., and Wu, C. 1999. ATP-dependent histone octamer sliding mediated by the chromatin remodeling complex NURF. Cell 97: 833–842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hassan A.H., Neely, K.E., and Workman, J.L. 2001. Histone acetyltransferase complexes stabilize swi/snf binding to promoter nucleosomes. Cell 104: 817–827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hassan A.H., Prochasson, P., Neely, K.E., Galasinski, S.C., Chandy, M., Carrozza, M.J., and Workman, J.L. 2002. Function and selectivity of bromodomains in anchoring chromatin-modifying complexes to promoter nucleosomes. Cell 111: 369–379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Land M.J.P.a.H. 1990. Advanced mammalian gene transfer: High titre retroviral vectors with multiple drug selection markers and a complementary helper-free packaging cell line. Nucleic Acids Res. 18: 3587–3596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langst G., Bonte, E.J., Corona, D.F., and Becker, P.B. 1999. Nucleosome movement by CHRAC and ISWI without disruption or trans-displacement of the histone octamer. Cell 97: 843–852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lis J.T., Mason, P., Peng, J., Price, D.H., and Werner, J. 2000. P-TEFb kinase recruitment and function at heat shock loci. Genes & Dev. 14: 792–803. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luft J.C., Benjamin, I.J., Mestril, R., and Dix, D.J. 2001. Heat shock factor 1-mediated thermotolerance prevents cell death and results in G2/M cell cycle arrest. Cell Stress Chaperones 6: 326–336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMillan D.R., Xiao, X., Shao, L., Graves, K., and Benjamin, I.J. 1998. Targeted disruption of heat shock transcription factor 1 abolishes thermotolerance and protection against heat-inducible apoptosis. J. Biol. Chem. 273: 7523–7528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Narlikar G.J., Phelan, M.L., and Kingston, R.E. 2001. Generation and interconversion of multiple distinct nucleosomal states as a mechanism for catalyzing chromatin fluidity. Mol. Cell 8: 1219–1230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Narlikar G.J., Fan, H.Y., and Kingston, R.E. 2002. Cooperation between complexes that regulate chromatin structure and transcription. Cell 108: 475–487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neish A.S., Anderson, S.F., Schlegel, B.P., Wei, W., and Parvin, J.D. 1998. Factors associated with the mammalian RNA polymerase II holoenzyme. Nucleic Acids Res. 26: 847–853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newton E.M., Knauf, U., Green, M., and Kingston, R.E. 1996. The regulatory domain of human heat shock factor 1 is sufficient to sense heat stress. Mol. Cell. Biol. 16: 839–846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phelan M.L., Sif, S., Narlikar, G.J., and Kingston, R.E. 1999. Reconstitution of a core chromatin remodeling complex from SWI/SNF subunits. Mol. Cell 3: 247–253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reinke H., Gregory, P.D., and Horz, W. 2001. A transient histone hyperacetylation signal marks nucleosomes for remodeling at the PHO8 promoter in vivo. Mol. Cell 7: 529–538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rougvie A.E. and Lis, J.T. 1988. The RNA polymerase II molecule at the 5′ end of the uninduced hsp70 gene of D. melanogaster is transcriptionally engaged. Cell 54: 795–804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schübeler D.a.J.B. 1997. A sensitive transcription assay based on a simplified nuclear run-on protocol. Tech. Tips Online 1: TO1176. [Google Scholar]

- Sif S., Stukenberg, P.T., Kirschner, M.W., and Kingston, R.E. 1998. Mitotic inactivation of a human SWI/SNF chromatin remodeling complex. Genes & Dev. 12: 2842–2851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soutoglou E. and Talianidis, I. 2002. Coordination of PIC assembly and chromatin remodeling during differentiation-induced gene activation. Science 295: 1901–1904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan E.K., Weirich, C.S., Guyon, J.R., Sif, S., and Kingston, R.E. 2001. Transcriptional activation domains of human heat shock factor 1 recruit human SWI/SNF. Mol. Cell. Biol. 21: 5826–5837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang H., Liu, Y., Madabusi, L., and Gilmour, D.S. 2000. Promoter-proximal pausing on the hsp70 promoter in Drosophila melanogaster depends on the upstream regulator. Mol. Cell. Biol. 20: 2569–2580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Utley R.T., Ikeda, K., Grant, P.A., Cote, J., Steger, D.J., Eberharter, A., John, S., and Workman, J.L. 1998. Transcriptional activators direct histone acetyltransferase complexes to nucleosomes. Nature 394: 498–502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitehouse I., Flaus, A., Cairns, B.R., White, M.F., Workman, J.L., and Owen-Hughes, T. 1999. Nucleosome mobilization catalysed by the yeast SWI/SNF complex. Nature 400: 784–787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson C.J., Chao, D.M., Imbalzano, A.N., Schnitzler, G.R., Kingston, R.E., and Young, R.A. 1996. RNA polymerase II holoenzyme contains SWI/SNF regulators involved in chromatin remodeling. Cell 84: 235–244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yudkovsky N., Logie, C., Hahn, S., and Peterson, C.L. 1999. Recruitment of the SWI/SNF chromatin remodeling complex by transcriptional activators. Genes & Dev. 13: 2369–2374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]