Abstract

We have reported that there is heterologous interaction between the mu, delta or kappa opioid receptors and the receptors for the chemokines CCL5/RANTES or CXCL12/SDF-1 in the regulation of antinociception in rats. CX3CL1/fractalkine, a chemokine that exclusively binds to CX3CR1, has been found to affect morphine analgesia and tolerance in the spinal cord. The purpose of the present study was to see if the interaction between the chemokine CX3CL1/fractalkine receptor and mu, delta or kappa opioid receptors occurs in the periaqueductal grey (PAG) of adult male S-D rats. The cold-water tail-flick (CWT) test was used to measure antinociception. The results showed that intra-PAG injection of 100 ng CX3CL1/fractalkine 30 min before administration of 400 ng DAMGO, 100 ng DPDPE or 20 μg dynorphin significantly reduced the antinociception induced by each of these peptides. These results demonstrate that activation of the CX3CL1 receptor diminishes the effect of mu, delta and kappa opioid agonists on their receptors in the PAG of rats.

Keywords: Chemokine, CX3CL1/fractalkine, Opioid Agonists, Antinociception, periaqueductal grey, Rats

1. Introduction

CX3CL1/fractalkine is a structurally unique chemokine reported to be constitutively expressed by neurons (Murphy et al., 2000). Chemokines, a family of cytokines that are chemoattractants for leukocytes, have similar structures and signal via G-protein-coupled receptors (GPCR) on the leukocytes. They have 4 subclasses of families: C family, CC family, CXC family and CX3C family (Murphy et al., 2000). Most chemokines (e.g., CCL5/RANTES), can bind to more than one chemokine receptor, but a few, like CXCL12/SDF-1 and CX3CL1/fractalkine, are specific to one receptor. CX3CL1/fractalkine’s only receptor, CX3CR1, is expressed predominantly by microglia and astrocytes (Boddeke et al., 1999; Lindia et al., 2005; Milligan et al., 2004), but has also been reported in hippocampal neurons (Meucci et al., 1998; Meucci et al., 2000). Opioid receptors are also members of the GPCR family. There are three major types of opioid receptors - mu, delta and kappa. Opioid receptors play important roles in many physiological functions, including modulation of pain perception and body temperature regulation (Adler and Geller 1993).

An interaction between opioids (mu and delta) and either the chemokine CCL5/RANTES or the chemokine CXCL12/SDF-1 alpha has been reported in vitro in chemotaxis and in vivo in the regulation of antinociception in rats (Grimm et al., 1998; Homan et al., 2002; Rogers et al., 2000; Rogers and Peterson 2003; Steele et al., 2002; Szabo and Rogers 2001; Szabo et al., 2001; Szabo et al., 2002; Zhang et al., 2004). The PAG is known to be the most important region of the brain involved in pain modulation (Basbaum and Fields, 1984). These chemokines and their receptors have been reported to be involved in blockade of the analgesic effects of opioids within the PAG (Szabo et al., 2002; Adler et al., 2006). On the basis of the studies showing their interference with opioid receptor function, the present experiments were designed to investigate the possibility of the interaction between the chemokine CX3CL1/fractalkine and mu, delta or kappa opioid agonists in antinociception in rats.

2. Results

2.1. The antinociceptive effect induced by PAG injection of CX3CL1/fractalkine

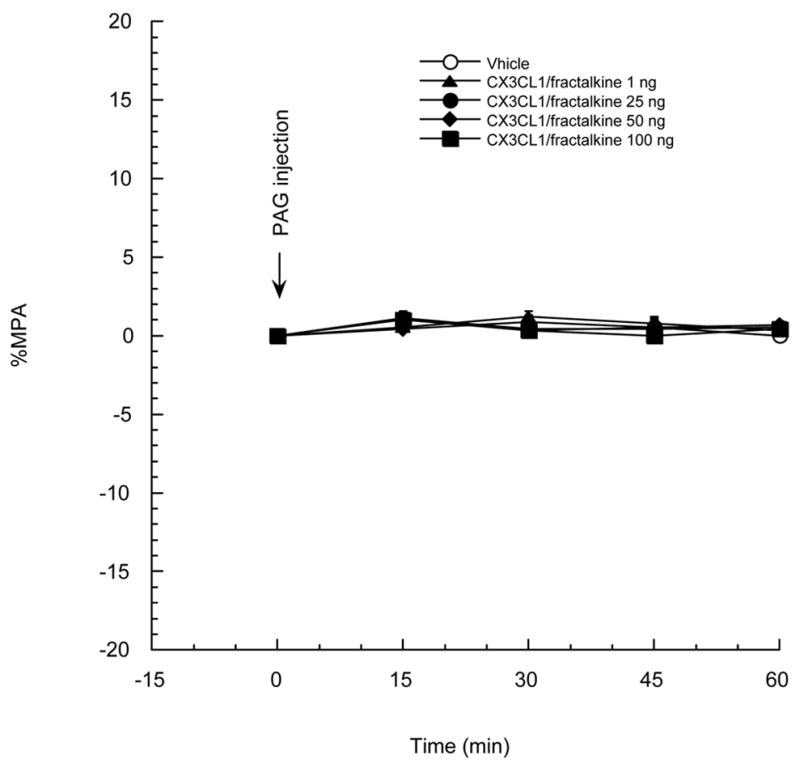

Rats were divided into 5 groups as follows: aCSF (vehicle), 1, 25, 50 and 100 ng CX3CL1/fractalkine. A PAG injection of CX3CL1/fractalkine or aCSF was given at time 0 as shown in Figure 1. CX3CL1/fractalkine, in the dose range tested, has no antinociceptive or hyperalgesic activity in the CWT test. A dose-dependence study for the chemokines CCL5/RANTES and CXCL12/SDF-1alpha on the analgesia induced by the mu opioid receptor agonist DAMGO (Szabo et al., 2002) showed that 100 ng CCL5/RANTES or CXCL12/SDF-1alpha totally blocked the DAMGO-induced analgesia. Thus, a dose of 100 ng CX3CL1/fractalkine was chosen for the subsequent experiments.

Figure 1.

Rats were divided into 5 groups and were given a PAG injection of CX3CL1/fractalkine 1, 25, 50, 100 ng or vehicle, respectively. P>0.05 between all two groups. N=5–6 per group. Each point represents the mean + SE.

2.2. The effect of intra-PAG injection of CX3CL1/fractalkine (100 ng) on the antinociceptive effect induced by DAMGO

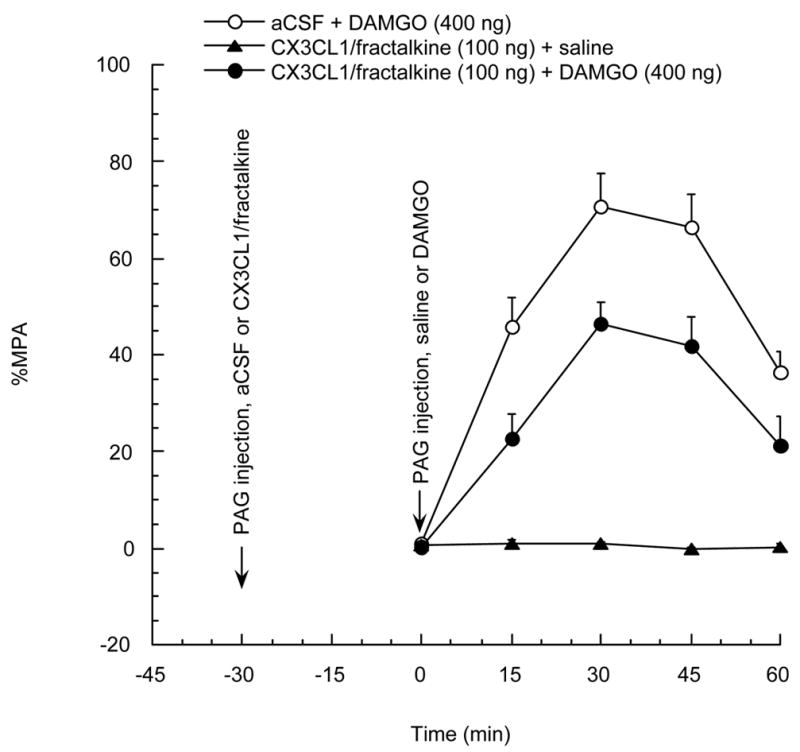

Rats were divided into 3 groups: aCSF + DAMGO, CX3CL1/fractalkine + saline, and CX3CL1/fractalkine + DAMGO. They were given a PAG injection of CX3CL1/fractalkine (100 ng) or vehicle a half-hour before PAG injection of saline or DAMGO. In figure 2, pretreatment with CX3CL1/fractalkine (100 ng) 30 min before DAMGO administration is shown to significantly reduce the antinociceptive effect induced by the mu opioid agonist DAMGO at a dose that has no effect by itself.

Figure 2.

Rats were divided into 3 groups and were given a PAG injection of CX3CL1/fractalkine 100 ng or vehicle 30 min before PAG injection of DAMGO 400 ng or saline, respectively. P<0.05 for aCSF + DAMGO group vs CX3CL1/fractalkine + DAMGO group. N=3–4 per group. Each point represents the mean + SE.

2.3. The effect of CX3CL1/fractalkine (100 ng, PAG) on the antinociceptive effect induced by DPDPE

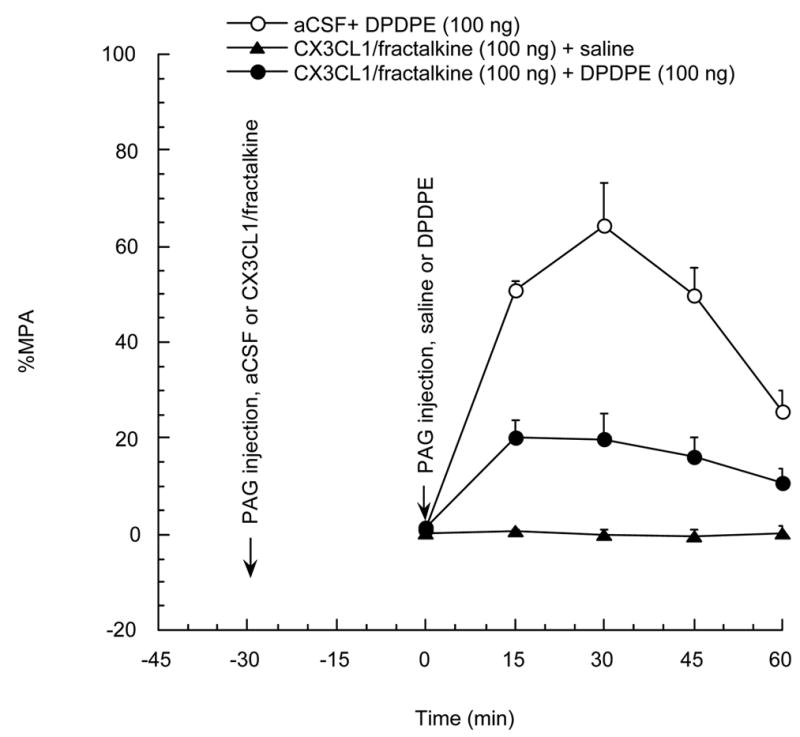

In this experiment, the design was similar to that in the previous one, except for substitution of the DAMGO by DPDPE. The results, shown in figure 3, demonstrated that CX3CL1/fractalkine (100 ng), 30 min before 100 ng DPDPE administration, significantly reduced the antinociceptive effect induced by the delta opioid agonist DPDPE.

Figure 3.

Rats were divided into 3 groups and were given a PAG injection of CX3CL1/fractalkine 100 ng or vehicle 30 min before PAG injection of DPDPE 100 ng or saline, respectively. P<0.05 for aCSF + DPDPE group vs CX3CL1/fractalkine + DPDPE group. N=3–4 per group. Each point represents the mean + SE.

2.4. The effect of CX3CL1/fractalkine (100 ng, PAG) on the antinociceptive effect induced by dynorphin (1–17)

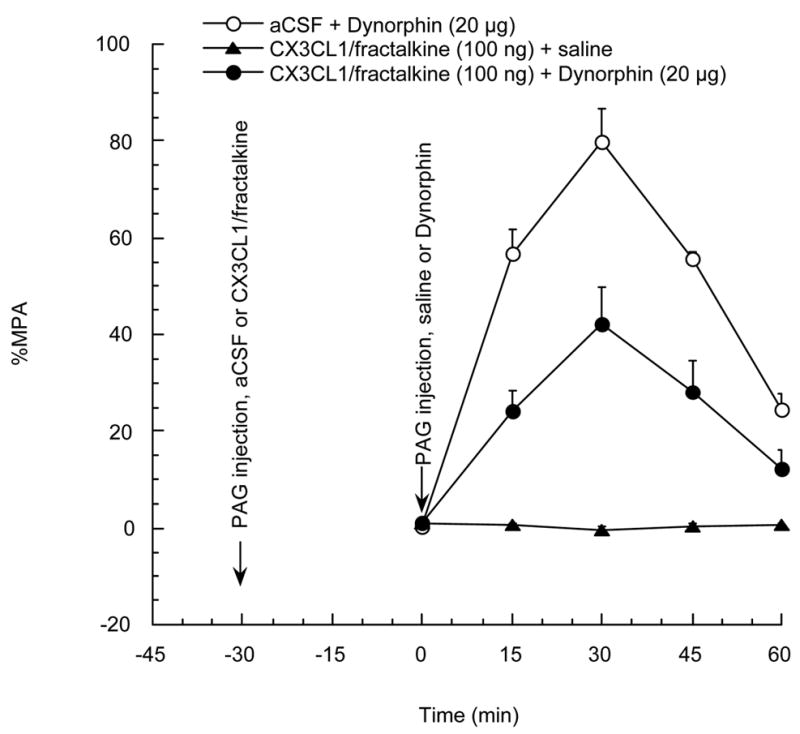

In this experiment, the design was similar to those with DAMGO or DPDPE, except for use of the kappa opioid agonist dynorphin. The data show that CX3CL1/fractalkine (100 ng), 30 min before the administration of 20 μg dynorphin, significantly reduced the antinociceptive effect induced by dynorphin (shown in figure 4).

Figure 4.

Rats were divided into 3 groups and were given a PAG injection of CX3CL1/fractalkine 100 ng or vehicle 30 min before PAG injection of dynorphin 20 μg or saline, respectively. P<0.05 for aCSF + dynorphin group vs CX3CL1/fractalkine + dynorphin group. N=3–5 per group. Each point represents the mean + SE.

3. Discussion

CX3CR1 is functionally unique among chemokine receptors in mediating direct cell-to-cell adhesion (Haskell et al., 1999; Imai et al., 1997). CX3CL1/fractalkine has been detected on neurons (Johnston et al., 2004) and has been found throughout rat brain (Milligan et al., 2004; Verge et al., 2004). This chemokine has been reported to be involved in atherogenesis and plaque destabilization in humans (Damas et al., 2005). It also appears to modulate the effects of intrathecal morphine, because coadministration of morphine with an intrathecal neutralizing antibody against the CX3CL1/fractalkine receptor potentiated acute morphine analgesia and attenuated the development of tolerance, hyperalgesia, and allodynia (Johnston et al., 2004).

DAMGO and DPDPE are synthetic opioid peptides that are selective for mu and delta opioid receptors, respectively (Handa et al., 1981; Mosberg et al., 1983). Dynorphin acts selectively on the kappa opioid receptor (Goldstein et al., 1979). All three opioid agonists produce significant antinociception in the CWT test (Chen et al., 1995; Xin et al., 1997). As shown in the above experiments, pretreatment with CX3CL1/fractalkine can significantly block the antinociceptive effect of the mu opioid receptor agonist DAMGO when both agents are administered into the PAG, the area of the brain most involved with analgesic responses. The kappa opioid receptor agonist dynorphin (1–17) and delta opioid receptor agonist DPDPE also show an antagonistic interaction with CX3CL1/fractalkine. Although CX3CL1/fractalkine has been reported to induce spinal nociceptive facilitation in the von Frey and Hargreaves tests (Milligan et al., 2005; Milligan et al., 2004), the results shown in figure 1 demonstrate that PAG injection of CX3CL1/fractalkine, at doses from 1 ng to 100 ng, is ineffective on its own and does not result in either antinociception or hyperalgesia in the CWT test. As compared to the total blockade by CCL5/RANTES and CXCL12/SDF-1 alpha of DAMGO antinociception (Szabo, et al., 2002), the same dose (100 ng, PAG) of CX3CL1/fractalkine in the present experiment only partially blocked the DAMGO antinociceptive effect. Intracerebroventricular administration of the opioid antagonist naloxone (1–10 μg) or the mu-selective antagonist CTAP (1 μg) antagonized morphine in a competitive fashion (Adams, et al., 1994). Because there is no evidence that chemokines can bind to opioid receptors, a naloxone-like antagonism is not a likely mechanism. The lack of a hyperalgesic effect of fractalkine makes a physiological antagonism also highly unlikely. For these reasons, in addition to our in vitro findings (Szabo et al., 2002), we suggest that a heterologous desensitization between chemokine and opioid receptors is the most plausible explanation.

Heterologous desensitization occurs when a GPCR, activated by an agonist, initiates a signaling process leading to the inactivation (desensitization) of an unrelated GPCR. Both the opioids and chemokines mediate their effects on leukocytes through the activation of GPCR. Oligomerization of mu, kappa and delta opioid receptors with the chemokine receptor CCR5 on the cell membrane of human or monkey lymphocytes has been reported and suggests that opioid receptors interact with CCR5 in cells coexpressing both receptors (Suzuki et al., 2002). The kappa opioid receptor has been shown to regulate thymocyte C-C Chemokine receptor 2 expression (Zhang and Rogers 2000) and a kappa agonist inhibits monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (CCL2) production by human astrocytes (Sheng et al., 2003) and SDF-1alpha receptor CXCR4 expression on CD4+ lymphocytes (Lokensgard et al., 2002). In addition, unpublished data from our collaborators indicate the co-localization of both opioid and chemokine receptors in several brain areas, including PAG (L. Kirby, personal communication). Thus, there is some evidence that heterologous desensitization may occur between mu, kappa or delta opioid receptors and CX3CL1/fractalkine receptors in the brain of rats.

Another possible explanation as to why fractalkine blocks the antinociception induced by opioid agonists might be that fractalkine binds to microglial cells (Verge et al., 2004), which then cause the release of proinflammatory cytokines (interleukin 1, IL-1) (Johnston et al., 2004; Milligan et al., 2005). It is possible that this may contribute to the results of the present study, as fractalkine-induced release of proinflammatory cytokines occurs very rapidly, in accord with the speed of effects observed here. In some reports (Johnston et al., 2004; Watkins et al., 2006; Shavit et al., 2005), IL-1 decreased the antinociceptive effects of morphine in the mice hot-plate tail-flick test and the rat thermal tail flick test. However, IL-1 has no antinociceptive effect alone nor did it affect morphine antinociception in the rat hot-plate test or in the cold-water (−3°C) tail-flick test (Adams et al., 1993).

Our laboratories were the first to report an apparent in vivo inactivation of mu and delta opioid receptors by chemoattractant factors CCR5 and CXCR4 (Chen et al., 2007; Szabo et al., 2002). Similarly, the present studies demonstrated the interaction between the mu, delta or kappa opioid agonists and CX3CL1/fractalkine in vivo. These findings suggest that the analgesic activity of the opioids in the brain can be overcome in situations in which there are elevated levels of chemokines and thus open up new avenues of research for pain management.

4. Experimental Procedures

4.1. Animals

Male Sprague-Dawley rats (Zivic-Miller), weighing 175–200 g, were housed in groups of 3–4 for at least 1 week in an animal room maintained at 22±1°C and approximately 50±5% relative humidity. Lighting was on a 12/12 h light/dark cycle (lights on at 7:00 and off at 19:00). All tests were performed during the light part of the rats’ light-dark cycle in the present experiments. Rats were allowed free access to food and water. All animal use procedures were conducted in strict accordance with the National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals, and were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

4.2. Surgery procedures

Rats were anesthetized with a mixture of ketamine hydrochloride (100–150 mg/kg) and acepromazine maleate (0.2 mg/kg). A sterilized stainless steel C313G cannula guide (22 gauge, Plastic One) was implanted into the lateral PAG and fixed with dental cement. The stereotaxic coordinates for PAG were as follows: bite bar 3.3 mm below 0, 7.8 mm posterior to bregma, 0.5 mm from midline and 5 mm ventral to the dura mater (Paxinos and Watson, 1998). A C313DC cannula dummy (Plastic One) of the identical length was inserted into the guide tube to prevent its occlusion. The animals were housed individually after surgery. Experiments began 1 week postoperatively. Each rat was used only once. At the end of the experiment, cannula placements were verified using microinjection of 1% bromobenzene blue according to the standard procedures in our laboratory (Xin et al., 1997).

4.3. Nociceptive test

The latency to flick the tail in cold water was used as the antinociceptive index, according to a standard procedure in our laboratory (Pizziketti et al., 1985). A 1:1 mix of ethylene glycol:water was maintained at −3°C with a circulating water bath (Model 9500, Fisher Scientific; Pittsburgh, PA). Rats were held over the bath with their tails submerged approximately half-way into the solution. All animals were tested at 60, 15 and 0 min before drug injection. For each animal, the first reading was discarded and the mean of the second and third readings was taken as the baseline value. Rats whose baseline values fell within a range of 10 to 20 s were used in the experiments. About 5% of them were discarded. Latencies to tail flick after injection were expressed as percentage change from baseline. The percentage of maximal possible antinociception (MPA%) for each animal at each time was calculated using the formula: %MPA = [(test latency − baseline latency)/(60 − baseline latency)] × 100. A cutoff limit of 60 s was set to avoid damage to the tail.

4.4. Drugs

The mu opioid receptor agonist (D-Ala2,N-Me-Phe4,Gly5-ol)enkephalin (DAMGO) (Handa et al., 1981), delta opioid receptor agonist [D-Pen2, D-Pen5]-enkephalin (DPDPE) (H-Tyr-D-Pen-Gly-Phe-D-Pen-OH) (Mosberg et al., 1983) and kappa opioid receptor agonist dynorphin A (1–17) (H-Tyr-Gly-Gly-Phe-Leu-Arg-Arg-Ile-Arg-Pro-Lys-Leu-Lys-Trp-Asp-Asn-Gln-OH) (Goldstein et al., 1979) were made by Multiple Peptide Systems, San Diego, CA. These drugs were dissolved in the 0.9% saline.

CX3CL1/fractalkine, a DNA sequence encoding the mature 76-amino-acid variant (amino acid residues 25 – 100) of the chemokine domain of the mature rat CX3CL1 protein sequence (Harrison et al., 1998), was obtained from R&D System, Minneapolis, MN. CX3CL1/fractalkine was dissolved in artificial cerebrospinal fluid (aCSF, CMA Microdialysis AB, MA).

4.5. Injections

One week after surgery, either chemokine and aCSF or opioid agonists and saline were injected into the PAG in a volume of 1.0 μl over a 30-second period. With aseptic procedures, the C313I internal cannula (28 gauge, Plastics One) was connected to a 10 μl Hamilton syringe by polyethylene tubing. CX3CL1/fractalkine was administered 30 min before 400 ng DAMGO, 100 ng DPDPE or 20 μg dynorphin.

4.6. Statistical analysis

The data are expressed as the mean and standard error. Statistical analysis of difference between groups was assessed with an analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Tukey’s test. P≤0.05 was taken as the significant level of difference.

Acknowledgments

We thank Margaret S. Deitz for PAG surgery assistance. This work was supported by Grants DA06650, DA11130, DA13429, DA-16544 and DA14230.

Abbreviations

- PAG

periaqueductal grey

- CWT

Cold water tail-flick test

- aCSF

artificial cerebrospinal fluid

- MPA%

the percentage of maximal possible antinociception

- DAMGO

(D-Ala2,N-Me-Phe4,Gly5-ol)enkephalin

- DPDPE

(H-Tyr-D-Pen-Gly-Phe-D-Pen-OH)enkephalin

- Dynorphin A (1-17)

H-Tyr-Gly-Gly-Phe-Leu-Arg-Arg-Ile-Arg-Pro-Lys-Leu-Lys-Trp-Asp-Asn-Gln-OH

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Adams JU, Bussiere JL, Geller EB, Adler MW. Pyrogenic doses of intracerebroventricular interleukin-1 did not induce analgesia in the rat hot-plate or cold-water tail-flick tests. Life Sci. 1993;53:1401–1409. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(93)90582-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adams JU, Geller EB, Adler MW. Receptor selectivity of icv morphine in the rat cold water tail-flick test. Drug Alcohol Depend. 1994;35:197–202. doi: 10.1016/0376-8716(94)90074-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adler MW, Geller EB, Chen XH, Rogers TJ. Viewing chemokines as a third major system of communication in the brain. AAPS Journal. 2006;7:E865–E870. doi: 10.1208/aapsj070484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adler MW, Geller EB. In Physiological Functions of Opioids: Temperature Regulation. In: Herz A, Akil H, Simon EJ, editors. Handbook of Experimental Pharmacology. Opioids II. Vol. 104/II. Springer-Verlag; Berlin: 1993. pp. 205–238. [Google Scholar]

- Basbaum AI, Fields HL. Endogenous pain control systems: brainstem spinal pathways and endorphin circuitry. Ann Rev Neurosci. 1984;7:309–338. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ne.07.030184.001521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boddeke HWGM, Meigel I, Frentzel S, Biber K, Renn LQ, Gebicke-Harter P. Functional expression of the fractalkine (CX3C) receptor and its regulation by lipopolysaccharide in rat microglia. Eur J Pharmacol. 1999;374:309–313. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(99)00307-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X, Geller EB, Rogers TJ, Adler MW. Rapid heterologous desensitization of antinociceptive activity between mu or delta opioid receptors and chemokine receptors in rats. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2007;88:36–41. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2006.09.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen XH, Adams JU, Geller EB, DeRiel JK, Adler MW, Liu-Chen L-Y. An antisense oligodeoxynucleotide to μ-opioid receptors inhibits μ-agonist-induced analgesia in rats. Eur J Pharmacol. 1995;275:105–108. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(95)00012-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Damas JK, Boullier A, Waehre T, Smith C, Sandberg WJ, Green S, Aukrust P, Quehenberger O. Expression of fractalkine (CX3CL1) and its receptor, CX3CR1, is elevated in coronary artery disease and is reduced during statin therapy. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2005;25:2567–2572. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000190672.36490.7b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein A, Tachibana S, Lowney LI, Hunkapiller M, Hood L. Dynorphin-(1–13), an extraordinarily potent opioid peptide. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1979;76:6666–6670. doi: 10.1073/pnas.76.12.6666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grimm MC, Ben-Baruch A, Taub DD, Howard OM, Resau JH, Wang JM, Ali H, Richardson R, Snyderman R, Oppenheim JJ. Opiates transdeactivate chemokine receptors: Delta and mu opiate receptor-mediated heterologous desensitization. J Exp Med. 1998;188:317–325. doi: 10.1084/jem.188.2.317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Handa BK, Lane AC, Lord JAH, Morgan BA, Rance MJ, Smith CFC. Analogues of beta-LPH61-64 possessing selective agonist activity at mu-opiate receptors. Eur J Pharmacol. 1981;70:531–540. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(81)90364-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrison JK, Jiang Y, Chen S, Xia Y, Maciejewski D, McNamara RK, Streit WJ, Salafranca MN, Adhikari S, Thompson DA, Botti P, Bacon KB, Feng L. Role for neuronally derived fractalkine in mediating interactions between neurons and CX3CR1-expressing microglia. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:10896–10901. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.18.10896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haskell CA, Cleary MD, Charo IF. Molecular uncoupling of fractalkine-mediated cell adhesion and signal transduction. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:10053–10058. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.15.10053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Homan JW, Steele AD, Martinand-Mari C, Rogers TJ, Henderson EE, Charubala R, Pfleiderer W, Reichenbach NL, Suhadolnik RJ. Inhibition of morphine-potentiated HIV-1 replication in peripheral blood mononuclear cells with the nuclease-resistant 2-5A agonist analog, 2-5AN6B. J Acquir Immun Defic Syndr. 2002;30:9–20. doi: 10.1097/00042560-200205010-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imai T, Hieshima K, Haskell C, Baba M, Nagira M, Nishimura M, Kakizaki M, Takagi S, Nomiyama H, Schall TJ, Yoshie O. Identification and molecular characterization of fractalkine receptor CX3CR1, which mediates both leukocyte migration and adhesion. Cell. 1997;91:521–530. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80438-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston IN, Milligan ED, Wiesler-Frank J, Frank MG, Zapata V, Campisi J, Langer S, Martin D, Green P, Fleshner M, Leinwand L, Maier SF. A role for proinflammatory cytokines and fractalkine in analgesia, tolerance, and subsequent pain facilitation induced by chronic intrathecal morphine. J Neurosci. 2004;24:9353–9365. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1850-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindia JA, McGowan E, Jochnowitz N, Abbadie C. Induction of CX3CL1 expression in astrocytes and CX3CR1 in microglia in the spinal cord of a rat model of neuropathic pain. J Pain. 2005;6:434–438. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2005.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lokensgard JR, Gekker G, Peterson PK. Kappa-opioid receptor agonist inhibition of HIV-1 envelope glycoprotein-mediated membrane fusion and CXCR4 expression on CD4(+) lymphocytes. Biochem Pharmacol. 2002;63:1037–1041. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(02)00875-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meucci O, Fatatis A, Simen AA, Bushell TJ, Miller RJ. Expression of CX3CR1 chemokine receptors on neurons and their role in neuronal survival. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:8075–8080. doi: 10.1073/pnas.090017497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meucci O, Fatatis A, Simen AA, Bushell TJ, Gray PW, Miller RJ. Chemokines regulate hippocampal neuronal signalling and gp120 neurotoxicity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:14500–14505. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.24.14500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milligan E, Zapata V, Schoeniger D, Chacur M, Green P, Poole S, Martin D, Maier SF, Watkins LR. An initial investigation of spinal mechanisms underlying pain enhancement induced by fractalkine, a neuronally released chemokine. Eur J Neurosci. 2005;22:2775–2782. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2005.04470.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milligan ED, Zapata V, Chacur M, Schoeniger D, Biedenkapp J, O’Connor KA, Verge GM, Chapman G, Green P, Foster AC, Naeve GS, Maier SF, Watkins LR. Evidence that exogenous and endogenous fractalkine can induce spinal nociceptive facilitation in rats. Eur J Neurosci. 2004;20:2294–2302. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2004.03709.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mosberg HI, Hurst R, Hruby VJ, Gee K, Yamamura HI, Galligan JJ, Burks TF. Bis-penicillamine enkephalins possess highly improved specificity towards _ opioid receptors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1983;80:5871–5874. doi: 10.1073/pnas.80.19.5871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy PM, Baggiolini M, Charo IF, Hebert CA, Horuk R, Matsushima K, Miller LH, Oppenheim JJ, Power CA. International union of pharmacology. XXII. nomenclature for chemokine receptors. Pharmacol Rev. 2000;52:145–176. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pizziketti RJ, Pressman NS, Geller EB, Cowan A, Adler MW. Rat cold water tail-flick: A novel analgesic test that distinguishes opioid agonists from mixed agonist-antagonists. Eur J Pharmacol. 1985;119:23–29. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(85)90317-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers TJ, Peterson PK. Opioid G protein-coupled receptors: Signals at the crossroads of inflammation. Trends Immunol. 2003;24:116–121. doi: 10.1016/s1471-4906(03)00003-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers TJ, Steele AD, Howard OMZ, Oppenheim JJ. Bidirectional heterologous desensitization of opioid and chemokine receptors. Ann NY Acad Sci. 2000;917:19–28. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2000.tb05369.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shavit Y, Wolf G, Goshen I, Livshits D, Yirmiya R. Interleukin-1 antagonizes morphine analgesia and underlies morphine tolerance. Pain. 2005;115:50–59. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2005.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheng WS, Hu S, Lokensgard JR, Peterson PK. U50,488 inhibits HIV-1 tat-induced monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (CCL2) production by human astrocytes. Biochem Pharmacol. 2003;65:9–14. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(02)01480-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steele AD, Szabo I, Bednar F, Rodgers TJ. Interactions between opioid and chemokine receptors: Heterologous desensitization. Cytokine & Growth Factor Rev. 2002;13:209–222. doi: 10.1016/s1359-6101(02)00007-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki S, Chuang LF, Yau P, Doi RH, Chuang RY. Interactions of opioid and chemokine receptors: Oligomerization of mu, kappa, and delta with CCR5 on immune cells. Exp Cell Res. 2002;280:192–200. doi: 10.1006/excr.2002.5638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szabo I, Chen XH, Xin L, Adler MW, Howard OMZ, Oppenheim JJ, Rogers TJ. Heterologous desensitization of opioid receptors by chemokines inhibits chemotaxis and enhances the perception of pain. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:10276–10281. doi: 10.1073/pnas.102327699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szabo I, Rogers TJ. In Crosstalk between Chemokine and Opioid Receptors Results in Downmodulation of Cell Migration. In: Friedman H, Klein TW, Madden JJ, editors. Neuroimmune Circuits, Drugs of Abuse, and Infectious Diseases. 2001. pp. 75–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szabo I, Wetzel MA, McCarthy L, Steele AD, Henderson EE, Howard OMZ, Oppenheim JJ, Rogers TJ. In Interactions of Opioid Receptors, Chemokines, and Chemokine Receptors. In: Friedman H, Klein TW, Madden JJ, editors. Neuroimmune Circuits, Drugs of Abuse, and Infectious Diseases. 2001. pp. 69–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verge GM, Milligan ED, Maier SF, Watkins LR, Naeve GS, Foster AC. Fractalkine (CX3CL1) and fractalkine receptor (CX3CR1) distribution in spinal cord and dorsal root ganglia under basal and neuropathic pain conditions. Eur J Neurosci. 2004;20:1150–1160. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2004.03593.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watkins LR, Hutchinson MR, Johnston IN, Maier SF. Glia: novel counter-regulators of opioid analgesia. Trends Neurosci. 2005;28:661–669. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2005.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xin L, Geller EB, Adler MW. Body temperature and analgesic effects of selective mu and kappa opioid receptor agonists microdialyzed into rat brain. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1997;281:499–507. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang L, Rogers TJ. K-opioid regulation of thymocyte IL-7 receptor and C-C chemokine receptor 2 expression. J Immunol. 2000;164:5088–5093. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.10.5088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang N, Rogers TJ, Caterina M, Oppenheim JJ. Proinflammatory chemokines, such as C-C chemokine ligand 3, desensitize μ-opioid receptors on dorsal root ganglia neurons. J Immunol. 2004;173:594–599. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.1.594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]