Abstract

During the earliest stages of Caenorhabditis elegans embryogenesis, the transcription factor SKN-1 initiates development of the digestive system and other mesendodermal tissues. Postembryonic SKN-1 functions have not been elucidated. SKN-1 binds to DNA through a unique mechanism, but is distantly related to basic leucine-zipper proteins that orchestrate the major oxidative stress response in vertebrates and yeast. Here we show that despite its distinct mode of target gene recognition, SKN-1 functions similarly to resist oxidative stress in C. elegans. During postembryonic stages, SKN-1 regulates a key Phase II detoxification gene through constitutive and stress-inducible mechanisms in the ASI chemosensory neurons and intestine, respectively. SKN-1 is present in ASI nuclei under normal conditions, and accumulates in intestinal nuclei in response to oxidative stress. skn-1 mutants are sensitive to oxidative stress and have shortened lifespans. SKN-1 represents a connection between developmental specification of the digestive system and one of its most basic functions, resistance to oxidative and xenobiotic stress. This oxidative stress response thus appears to be both widely conserved and ancient, suggesting that the mesendodermal specification role of SKN-1 was predated by its function in these detoxification mechanisms.

Keywords: Oxidative stress, C. elegans, SKN-1, mesendoderm, intestine, lifespan

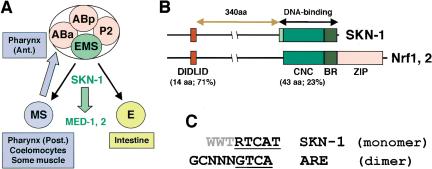

In diverse organisms, a common mesendodermal tissue field gives rise to the endoderm and a mesoderm subset that forms the heart and blood in vertebrates (Reiter et al. 1999; Warga and Nusslein-Volhard 1999; Rodaway and Patient 2001). In the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans, mesendodermal development is initiated by the transcription factor SKN-1, which was identified in a screen for genes that are required maternally for formation of pharyngeal tissue (Bowerman et al. 1992). Maternally expressed SKN-1 specifies the fate of a single cell, the EMS blastomere (Fig. 1A). The EMS daughter cell E becomes the endoderm, which consists of the intestine. Its sister cell MS gives rise to mesodermal derivatives that include the posterior portion of the pharynx, a feeding pump that is analogous to the heart, and coelomocytes that resemble macrophages. The anterior pharynx is specified in ABa descendants by a SKN-1-dependent signal from MS. In skn-1 mutants, these lineages instead give rise to excess hypodermis (Bowerman et al. 1992).

Figure 1.

SKN-1 embryonic functions and comparison to Nrf proteins. (A) Cell fate specification. In four-cell embryos, SKN-1 initiates mesendodermal development by establishing the EMS blastomere fate (Bowerman et al. 1992). Anterior is to the left, and ventral at the bottom. (B) SKN-1 compared to Nrf proteins. The SKN-1 minor groove-binding arm is shown in light green. The percent identity between SKN-1 and mouse Nrf2 regions is indicated. (C) Consensus sequences for SKN-1 binding and the ARE. The SKN-1 BR recognizes a consensus bZIP half-site (underlined) adjacent to an AT-rich motif (gray) that is specified by the arm (B). Nrf proteins bind to the ARE as obligate heterodimers with Maf or other bZIP proteins (Hayes and McMahon 2001). (R) G/A; (W) T/A.

SKN-1 directly induces expression of the GATA factors MED-1 and MED-2, which are required for mesendodermal differentiation in the EMS lineage (Fig. 1A; Maduro et al. 2001). Remarkably, counterparts of the MED proteins (GATA4, GATA5, and GATA6) and of various downstream transcription factors involved in C. elegans mesendodermal development appear to play surprisingly similar roles in vertebrates (Haun et al. 1998; Reiter et al. 1999; Shoichet et al. 2000; Rodaway and Patient 2001; Lickert et al. 2002; Maduro and Rothman 2002). These similarities suggest that certain key regulatory mechanisms involved in mesendodermal differentiation have been maintained during evolution.

Although many aspects of mesendodermal development appear to be conserved, it is striking that SKN-1 is distinct from any other known protein because of its DNA-binding mechanism. SKN-1 binds to DNA with high affinity as a monomer through a basic region (BR) like those of basic leucine-zipper (bZIP) proteins, which are obligate dimers (Fig. 1B; Blackwell et al. 1994). SKN-1 lacks a ZIP segment, which is essential for bZIP protein DNA binding because it acts as a dimerization element, and stabilizes folding of the BR on the DNA (Talanian et al. 1990). In contrast, monomeric SKN-1 DNA binding is comparably stabilized by a flexible “arm” that binds in the minor groove, and by a novel variant of the CNC region, through which SKN-1 is distantly related to a bZIP protein subgroup (Blackwell et al. 1994; Carroll et al. 1997; Kophengnavong et al. 1999). SKN-1 is also similar to two vertebrate CNC-group proteins (NF-E2-related factors Nrf1 and Nrf2) within a 14-amino-acid transactivator element (DIDLID; Fig. 1B; Walker et al. 2000). These limited similarities suggest that although SKN-1-like proteins have not been identified outside of nematodes, SKN-1 and these particular bZIP proteins might share a common precursor.

In vertebrates, Nrf proteins activate transcription of genes encoding the Phase II detoxification enzymes, which constitute the primary cellular defense against oxidative stress (Hayes and McMahon 2001; Thimmulappa et al. 2002). Essentially all organisms must defend themselves against reactive oxygen species (ROS), which are derived from both mitochondrial respiration and exogenous sources. Phase II enzymes synthesize the critical reducing agent glutathione, scavenge ROS directly, and detoxify reactive intermediates that are generated when xenobiotics are metabolized by the cytochrome p450 (Phase I) enzymes. Through Nrf2, exposure to oxidative stress or particular classes of chemicals induces Phase II enzyme gene expression in a variety of tissues, including the liver and digestive tract (Itoh et al. 1997; Hayes and McMahon 2001; Wolf 2001). This mechanism also constitutes the major response to chemoprotective antioxidants, including many natural compounds, which thereby stimulate xenobiotic detoxification and inhibit carcinogen-induced tumorigenesis. Accordingly, mice that lack Nrf2 are abnormally susceptible to drug toxicity and carcinogenesis, and do not respond to chemoprotective antioxidants (Chan and Kan 1999; Chan et al. 2001; Ramos-Gomez et al. 2001; Fahey et al. 2002).

Nrf-related bZIP proteins regulate Phase II genes in Saccharomyces cerevisiae (Yap1p) and Schizosaccharomyces pombe (Pap1p; Toone et al. 2001), suggesting that this ROS response may be generally conserved among eukaryotes. It has therefore been perplexing that bZIP orthologs of these proteins are not present in C. elegans. One possibility is that C. elegans has developed different mechanisms of regulating Phase II detoxification genes. Alternatively, the limited similarities between SKN-1 and Nrf proteins raise the surprising possibility that despite its unique DNA-binding mechanism, SKN-1 might be functionally related to Nrf proteins. skn-1 has postembryonic functions that have not been characterized: although homozygotes of all skn-1 alleles are viable and fertile, heterozygotes between skn-1 and a corresponding deficiency (nDf41) usually die with abnormal intestines (Bowerman et al. 1992). Although this suggests that existing skn-1 alleles might not be true nulls, it also indicates that skn-1 has functions in the differentiated intestine.

Here we have determined that during postembryonic stages, SKN-1 functions similarly to Nrf proteins in responses to oxidative stress, and that skn-1 is required for oxidative stress resistance and longevity. Expression of a key ROS-resistance gene is regulated independently of skn-1 in some C. elegans tissues, however, indicating that metazoans customize oxidative stress defenses for different organ contexts. The oxidative stress response mediated by SKN-1 appears to be conserved among C. elegans, vertebrates, and single-celled eukaryotes, implying that this is an ancient pathway, and that the role of SKN-1 in initiating mesendodermal development may have arisen from this detoxification mechanism.

Results

Constitutive and inducible Phase II detoxification gene activation by SKN-1

Vertebrate Nrf proteins induce expression of Phase II detoxification enzyme genes by binding to the characteristic antioxidant response element (ARE) in their promoters (Fig. 1C; Hayes and McMahon 2001). We have searched for SKN-1-binding sites within the predicted promoters of C. elegans orthologs of these oxidative-stress-resistance genes. The SKN-1-binding site preference and the ARE are distinct but not mutually exclusive (Fig. 1C). A predicted SKN-1 site should appear randomly every 2048 bp, but between two and four SKN-1 sites are present within 1 kb upstream of multiple C. elegans genes that encode predicted Phase II detoxification enzymes, including γ-glutamine cysteine synthetase heavy chain [GCS(h)], glutathione synthetase, and four glutathione S-transferase (GST) isoforms (Table 1). In vertebrates, each of these genes is activated by Nrf proteins (Hayes and McMahon 2001). SKN-1 sites or variants that differ at only one AT-rich region position are similarly present 5′ of the Nrf target NADH quinone oxidoreductase, the catalase ctl-1, and superoxide dismutases (sod-1, sod-2, and sod-3; Table 1).

Table 1.

Predicted SKN-1-binding sites upstream of C. elegans oxidative stress-resistance genes

| Enzymes | Gene or ORF | Locationa | Direction | Sequence |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| γ-Glutamyl-cysteine synthetase heavy chain (GCS(h)) | gcs-I | −121 | → | TTTATCAT |

| −316 | ← | ATGACTTA | ||

| −607 | ← | ATGACAAT | ||

| Glutathione synthetase | M176.2 | −137 | → | TTTGTCAT |

| −169 | ← | ATGACAAA | ||

| −243 | → | TTTATCAT | ||

| −378 | ← | ATGATTTT | ||

| NADH quinone oxidoreductase | F39B2.3 | −469 | → | GTTATCAT |

| −518 | ← | ATGACAAT | ||

| Glutathione S-transferase | R03D7.6 | −149 | ← | ATGACAAT |

| −282 | ← | ATGATTTT | ||

| −302 | ← | ATGACATT | ||

| −947 | ← | ATGATTTT | ||

| F35E8.8 | −94 | ← | ATGACAAT | |

| −240 | ← | ATGATAAT | ||

| F11G11.2 | −133 | ← | ATGACAAA | |

| −391 | → | CTTATCAT | ||

| K08F4.7 | −83 | ← | ATGACATT | |

| −157 | → | TTTGTCAT | ||

| Superoxide dismutase | sod-1 | −64 | → | ATAATCAT |

| sod-2 | −191 | → | TGTATCAT | |

| −363 | ← | ATGACAAT | ||

| −959 | → | AGAATCAT | ||

| −980 | → | AGAATCAT | ||

| sod-3 | −287 | → | TAAATCAT | |

| Catalase | ctl-1 | −880 | → | ATGATCAT |

| −978 | → | GTCATCAT | ||

| −997 | → | CTTATCAT |

The SKN-1-binding consensus is shown in Figure 1C.

The A within the translation initiation codon is designated as base 1.

The presence of SKN-1 site clusters upstream of multiple C. elegans Phase II detoxification genes is consistent with SKN-1 functioning analogously to Nrf proteins. To test this hypothesis, we investigated whether SKN-1 is required to express the Phase II gene gcs-1 (Table 1). gcs-1 is the C. elegans ortholog of GCS(h), a representative and well-characterized Nrf-protein target gene that in yeast is regulated by Yap1p and Pap1p (Toone and Jones 1999; Hayes and McMahon 2001). The GCS(h) enzyme is important for oxidative stress resistance because it is rate-limiting for glutathione synthesis.

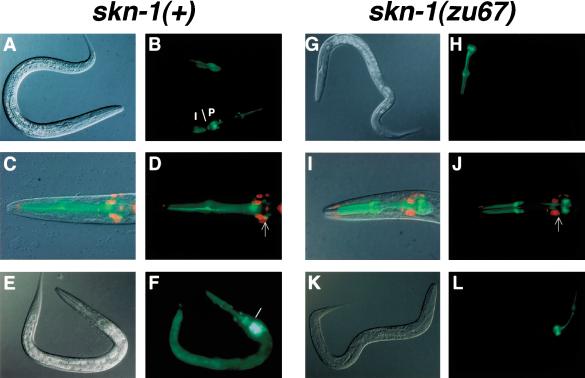

We investigated gcs-1 expression in C. elegans using a transgene that included the predicted gcs-1 promoter, along with the 17 N-terminal GCS-1 amino acids fused to green fluorescent protein (GFP). This promoter segment contained three consensus SKN-1-binding sites, and corresponded to the intervening sequence between gcs-1 and the nearest upstream gene (data not shown). With this strategy, we could analyze gcs-1 expression independently of GCS-1 protein stability. In a wild-type background, during larval and adult stages GCS-1::GFP was readily detectable in the pharynx, and in nearby cells that appeared to be neurons (Fig. 2A,B). By soaking gcs-1::gfp lines in DiI, a dye that fills amphid sensory neurons (Herman and Hedgecock 1990), we determined that two GCS-1::GFP-expressing cells located adjacent to the posterior pharynx correspond to the ASI chemosensory neurons (Fig. 2C,D), which prevent constitutive entry into the dauer diapause state (Ren et al. 1996; Schackwitz et al. 1996). GCS-1::GFP expression was also apparent anteriorly and posteriorly in the intestine (Fig. 2A,B).

Figure 2.

skn-1-dependent GCS-1::GFP expression in the intestine and ASI neurons. (A-F) GCS-1::GFP expression in wild-type animals. A gcs-1 genomic fragment containing its 17 N-terminal codons and 1840 upstream base pairs was fused to the N terminus of GFP, which contained a nuclear localization signal. The expression patterns shown are each representative of more than two independent transgenic lines, and of all postembryonic stages examined (L2-adult; data not shown). (A,B) Nomarski (A) and fluorescent (B) views of an L2 larva. (B) A line demarcates the approximate boundary between the anterior intestine (I) and posterior pharynx (P). (C,D) Combined Nomarski/fluorescent (C) and fluorescent (D) views of the head of a typical L4-stage animal that had been exposed to DiI. (D) One of the two ASI neurons is indicated with an arrow. (E,F) An L2 larva in which GCS-1::GFP expression was induced to high levels in the intestine by heat. A similar induction occurred in response to paraquat (Table 2). The boundary between the anterior intestine and posterior pharynx is indicated as in B. (G-L) GCS-1::GFP was not detectable outside of the pharynx in skn-1 homozygotes. Typical animals are shown from experiments that parallel those displayed to the left in A-F. Note the absence of GCS-1::GFP in the intestine and ASI neurons under normal conditions (G-J), and after treatment with heat (K,L) or paraquat (data not shown). In two independent transgenic lines, in a homozygous skn-1 background GCS-1::GFP expression was not detected in these tissues in any animals under either normal or induction conditions.

In vertebrates, oxidative stress induces Phase II gene expression through an Nrf2-dependent pathway in the intestine and liver (Itoh et al. 1997; Hayes and McMahon 2001). Similarly, stimuli that cause oxidative stress dramatically increased GCS-1::GFP expression in the C. elegans intestine (Fig. 2E,F; Table 2). This response was triggered by both heat and the herbicide paraquat (methyl viologen), which generates intracellular superoxide anions. To investigate the involvement of skn-1 in gcs-1 expression, we introduced the gcs-1::gfp transgene into the skn-1(zu67) background, the skn-1 allele that is associated with the most severe embryonic phenotype (Bowerman et al. 1992). Under both normal and oxidative stress conditions, in skn-1(zu67) homozygotes GCS-1::GFP was apparent at wild-type levels in the pharynx, but was otherwise undetectable (Fig. 2G-L), indicating that skn-1 is essential for both constitutive and inducible gcs-1::gfp expression outside of the pharynx.

Table 2.

Induction of GCS-1::GFP expression in the intestine by oxidative stress

|

gcs-1::gfp

|

gcsδ2::gfp

|

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Inducer | Low | Medium | High | N | Low | Medium | High | N |

| Control | 90.8% | 7.9% | 1.3% | 76 | 88.2% | 10.3% | 1.5% | 68 |

| Heat shock | 10.5% | 72.4% | 17.1% | 76 | 0.0% | 14.0% | 86.0% | 86 |

| paraquat | 14.5% | 67.1% | 18.4% | 76 | 21.3% | 65.6% | 13.1% | 61 |

A representative set of experiments involving a mixed population of L2-young adult worms is shown, from which the percentages of animals in each expression category are listed. Induction of GCS-1::GFP expression was comparable among the different developmental stages analyzed. “Low” refers to animals similar to that in Figure 2A, in which intestinal GCS-1::GFP was apparent at modest levels anteriorly, or anteriorly and posteriorly. “High” indicates that GCS-1::GFP was present at high levels anteriorly and detectable throughout most of the intestine, as in Figure 2F. “Medium” refers to animals in which GCS-1::GFP was present at high levels anteriorly as in Figure 2F and possibly posteriorly, but was not detected in between. N indicates the number of animals analyzed from each transgenic strain.

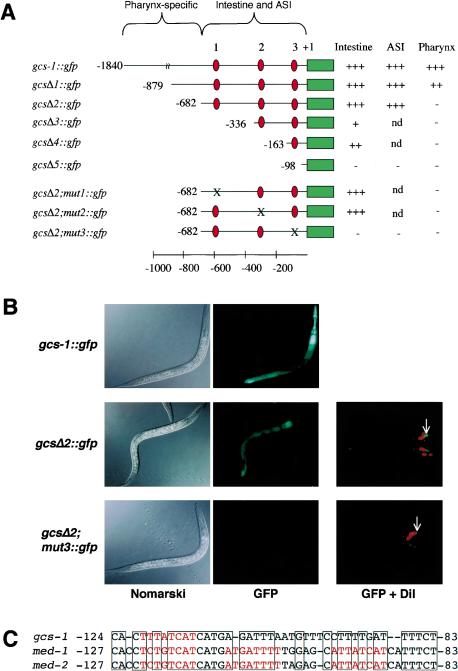

Promoter mutagenesis identified discrete elements that are required for these skn-1-dependent and -independent gcs-1 expression patterns. Pharyngeal GCS-1::GFP expression was abolished by removal of the distal gcs-1 promoter region (gcsΔ2::gfp; Fig. 3A,B), which lacks SKN-1-binding sites but contains consensus sites for the pharyngeal transcription factors PEB-1 and PHA-4 (Thatcher et al. 2001; Gaudet and Mango 2002; data not shown). The remaining proximal 682 bp of the gcs-1 promoter included the three predicted SKN-1-binding sites, and was sufficient for appropriate GCS-1::GFP expression in the intestine and ASI neurons (gcsΔ2::gfp; Fig. 3A,B; Table 2). Constitutive and stress-induced GCS-1::GFP expression within the intestine and ASI neurons did not require SKN-1-binding sites 1 or 2 individually, but was abolished by alteration of site 3 (gcsΔ2; mut3::gfp; Fig. 3A,B; see Materials and Methods).

Figure 3.

Specific elements required for skn-1-independent and -dependent GCS-1::GFP expression. (A) Analysis of the gcs-1 promoter. The expression of the indicated constructs from transgenic extrachromosomal arrays was assayed in two to three independent transgenic lines under normal conditions, and after induction by paraquat and heat. The relative expression levels in the tissues designated to the right (data not shown) are indicated by plus signs, with ++ indicating a reproducible reduction and + indicating barely detectable expression. Within each set of transgenic lines that carried promoter mutations, levels of normal and induced expression were affected in parallel. Mutations that were created in predicted SKN-1 sites 1, 2, and 3 are described in Materials and Methods, and are not compatible with SKN-1 binding (Blackwell et al. 1994; see text). Red ovals indicate predicted SKN-1 binding sites and a green bar indicates the 5′-end of the gcs-1::gfp coding region. Map numbers refer to the predicted translation start. (B) Uncoupling pharyngeal GCS-1::GFP expression from intestinal and ASI neuron expression. The gcsΔ2 mutation eliminated pharyngeal GCS-1::GFP expression, but allowed near-wild-type levels of ASI and intestinal expression. Concurrent ablation of SKN-1 binding site 3 (gcsΔ2, mut3) eliminated transgene expression in all tissues. Paraquat-treated worms are shown in the GFP column. (C) Composite gcs-1 promoter element that includes SKN-1 site 3, and is also present in the med-1 and med-2 promoters. SKN-1 binding sites are red, and identical sequences are boxed.

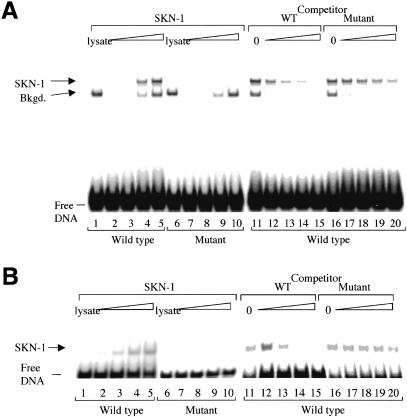

Remarkably, SKN-1-binding site 3 is located within a 42-bp gcs-1 promoter element that is similar to a composite motif through which SKN-1 activates med-1 and med-2 in the embryo (Figs. 1A, 3C; Maduro et al. 2001). The conservation between these gcs-1 and med promoter elements is particularly striking because they are located at identical distances from their respective translation starts, but contain different numbers of SKN-1 sites (Fig. 3C). In an electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA), full-length SKN-1 and the 85-amino-acid SKN-1 DNA-binding domain (SKN Domain; Blackwell et al. 1994) each bound sequence-specifically to SKN-1-binding site 3 in the context of this gcs-1 promoter element (Fig. 4). These SKN-1 proteins bound with high affinity to an oligonucleotide that corresponds to this composite element (wild type; Fig. 4A,B, lanes 2-5), but not to an analogous probe in which SKN-1 site 3 had been altered as in the inactive gcsΔ2; mut3::gfp transgene (Fig. 3A; mutant, Fig. 4A,B, lanes 7-10). Binding of these SKN-1 proteins to the wild-type probe was also competed much more effectively by unlabeled wild-type than mutant DNA (Fig. 4A,B, lanes 11-20). Further supporting the importance of this gcs-1 promoter element, a 163-bp fragment that includes it provides significant GCS-1::GFP expression in the intestine, but 5′ truncation within this sequence inactivates the promoter (gcsΔ4::gfp and gcsΔ5::gfp; Fig. 3A). In addition, an apparent counterpart to SKN-1 site 3 is present within 200 bp of the translation start site of the Caenorhabditis briggsae gcs-1 gene (data not shown). We conclude that binding of SKN-1 to site 3 is required for gcs-1 expression in the intestine and ASI neurons.

Figure 4.

Specific binding of SKN-1 to an essential gcs-1 promoter sequence. (A) Binding of full-length SKN-1 to site 3 within the gcs-1 composite element, assayed by EMSA. (Lanes 2-5) Binding of increasing amounts of in vitro translated SKN-1 protein (0, 0.25, 0.5, and 3 μL translation lysate; indicated by a triangle) to the wild-type site. (Lane 1) Binding to 3 μL of un-programmed lysate. A background species is labeled. (Lanes 6-10) The same assay performed with the mutant probe. (Lanes 11-20) SKN-1 DNA binding is assayed in the presence of the indicated unlabeled competitor oligonucleotides. Lanes 12-15 and 17-20 correspond to addition of a 20-, 50-, 150-, and 400-fold molar excess of competitor over the labeled wild-type DNA. (B) The in vitro translated SKN-1 DNA-binding domain (Fig. 1B) binds specifically to the gcs-1 composite element. Binding was assayed as in A.

SKN-1 expression and accumulation in intestinal nuclei in response to oxidative stress

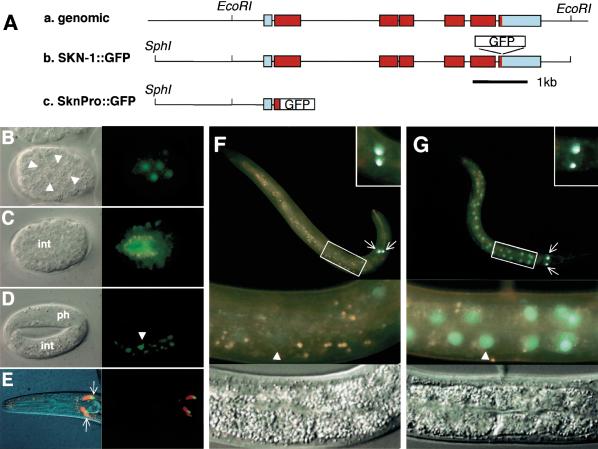

Postembryonic expression of SKN-1 has not been investigated previously. To determine whether SKN-1 is present in tissues where it is required for gcs-1::gfp expression, we analyzed expression of a transgene in which GFP is fused to the C terminus of full-length SKN-1 (SKN-1::GFP; Fig. 5A). Although maternal skn-1::gfp expression was not readily detectable because of germline transgene silencing (Kelly et al. 1997), at a low frequency this transgene rescued the embryonic defect in skn-1(zu67) homozygotes (data not shown), indicating that this SKN-1::GFP fusion protein is functional.

Figure 5.

Expression and stress-induced nuclear accumulation of SKN-1::GFP. (A) SKN-1::GFP transgenes. (a) skn-1 gene. Transcribed coding and untranslated regions are indicated in red and blue, respectively. (b) SKN-1::GFP translational fusion construct, which includes an EcoRI fragment that previously rescued maternal skn-1 lethality (Bowerman et al. 1992). C. elegans DNA is indicated by a black line. (c) SknPro::GFP promoter fusion, in which the 38 N-terminal SKN-1 amino acids are fused to GFP containing a nuclear localization signal. (B-D) Embryonic expression of SKN-1::GFP. Nomarski (left) and fluorescent (right) views of 100-cell (B), 280-min (C), and threefold (D) embryos. Endogenous intestinal autofluorescence is visible as yellow or orange (see Materials and Methods). White triangles, intestine precursor nuclei; int, intestine; ph, pharynx. (E) SKN-1::GFP expression in ASI neurons (arrows). Nomarski/fluorescent (left) and fluorescent (right) views are shown of a typical DiI-exposed L4 larva. (F) Larval SKN-1::GFP expression under normal conditions. (Bottom) Fluorescent and Nomarski closeups of the boxed central region of this L2. An intestinal nucleus is indicated by a white triangle, and the ASI neurons (arrows) are shown in detail in the top right box. (G) SKN-1::GFP localization under oxidative stress. A heat-shocked L2 is shown, but similar results were obtained after exposure to other oxidative stress inducers (Table 3). The integrated strain Is007 is shown, but two extrachromosomal lines and a different integrated line exhibited similar patterns.

In the embryo, antibody staining previously revealed the presence of maternal SKN-1 in nuclei through the eight-cell stage, then detected zygotically expressed SKN-1 in only -15% of late-stage embryos that had ceased dividing (Bowerman et al. 1993). We uniformly detected nuclear SKN-1::GFP in intestinal precursors beginning at the 50-100-cell stage (Fig. 5B), then in both the intestine and hypodermis (Fig. 5C), indicating that SKN-1 is expressed zygotically earlier than it is detectable by antibody staining. In late-stage embryos, SKN-1::GFP was also present in intestinal nuclei but not in the hypodermis (Fig. 5D), suggesting that hypodermal skn-1 expression may be maintained by a region located outside of this transgene.

In contrast to the embryo, in larvae and young adults, SKN-1::GFP was usually present at very low levels in intestinal nuclei (Fig. 5F; Table 3). SKN-1::GFP was readily detectable in the ASI neurons, where gcs-1::gfp was constitutively expressed (Fig. 5E,F), but not in other cells in the head, where GCS-1::GFP expression appeared to be skn-1-dependent (Fig. 2B,H). The latter skn-1 dependence might be indirect, or derived from low-level SKN-1 expression or distant skn-1 regulatory regions. The finding that SKN-1::GFP is present at only modest levels in intestinal nuclei raises the question of how oxidative stress induces skn-1-dependent intestinal gcs-1 expression (Figs. 2, 3; Table 2). In cultured mammalian cells, Nrf2 is stabilized and relocalized from the cytoplasm to the nucleus in response to oxidative stress (Itoh et al. 1999; Sekhar et al. 2002; Nguyen et al. 2003; Stewart et al. 2003). A promoter fusion transgene in which only the SKN-1 N terminus was linked to GFP (SknPro::GFP; Fig. 5A) was constitutively expressed at high levels in all intestinal cells (data not shown), suggesting that SKN-1 expression or localization might also be regulated posttranscriptionally by oxidative stress.

Table 3.

Accumulation of SKN-1::GFP in intestinal nuclei in response to oxidative stress

| Inducer | Low | Medium | High | N |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | 78.9% | 14.5% | 6.6% | 76 |

| Heat | 5.6% | 11.9% | 82.5% | 143 |

| Paraquat | 53.1% | 43.8% | 3.1% | 64 |

| M9, 5 min | 74.7% | 17.6% | 7.7% | 91 |

| 50 mM sodium azide, 5 min | 0.8% | 44.2% | 55.0% | 120 |

Mixed-stage L2-young adult transgenic worms were exposed to the indicated conditions. A representative set of experiments is shown, from which the percentages of animals in each category are listed. SKN-1 localization patterns did not differ significantly among the different developmental stages examined. M9 refers to the control incubation for the sodium azide experiment. In some animals treated with sodium azide, high levels of nuclear SKN-1 ::GFP appeared in <1 min (data not shown). “Low” refers to animals in which SKN-1 ::GFP was barely detectable in all intestinal nuclei, as shown in Figure 4F. “High” indicates that a very strong SKN-1 ::GFP signal was present in all intestinal nuclei, as in Figure 4G. “Medium” refers to animals in which nuclear SKN-1 ::GFP was present at high levels anteriorly or anteriorly and posteriorly, but was barely detectable midway through the intestine. N indicates the number of animals analyzed in each category.

After exposure to either paraquat or heat, neither the location nor intensity of SKN-1::GFP was detectably altered in the ASI neurons, but in a high percentage of animals, elevated levels of SKN-1::GFP appeared in intestinal cell nuclei, particularly anteriorly and posteriorly, where GCS-1::GFP is most robustly expressed (Fig. 5F,G; Table 3). SKN-1::GFP accumulated in intestinal nuclei within 5 min after treatment with 50 mM sodium azide (Table 3), which induces oxidative stress by blocking mitochondrial electron transport. The rapidity of this last response indicates that SKN-1 is constitutively present in the intestine but may be diffuse within the cytoplasm and masked by autofluorescence. This accumulation of SKN-1::GFP in intestinal nuclei in response to oxidative stress remarkably parallels the skn-1-dependent induction of GCS-1::GFP under similar conditions, supporting the model that SKN-1 activates intestinal gcs-1 expression directly.

skn-1 required for oxidative stress resistance and normal longevity

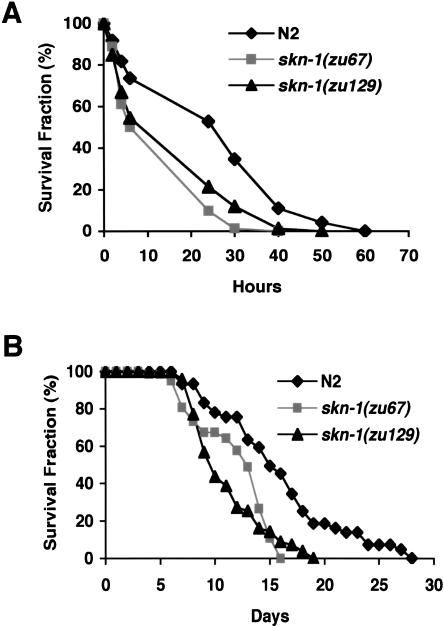

The functional similarities between SKN-1 and Nrf proteins that we have identified predict that skn-1 mutants may be abnormally sensitive to oxidative stress. skn-1(zu67) homozygotes produce normal numbers of off-spring with normal timing, and as young adults are not obviously distinguishable in morphology from wild type (data not shown). Two different skn-1 mutant alleles are associated with markedly decreased survival in the presence of paraquat, however, indicating that skn-1 mutants are sensitive to oxidative stress (Fig. 6A).

Figure 6.

skn-1 mutants are sensitive to oxidative stress and have reduced lifespans. (A) Paraquat sensitivity. Individual worms were scored for survival at the times shown after they had been placed in M9 that contained 100 mM paraquat. An average of three experiments involving 24 worms each is graphed. Among these experiments, for skn-1(zu67) and skn-1(zu129) animals, the mean survival times expressed as percentage of wild type were 52.9% ± 9.5% and 60.7% ± 16.1%, respectively. All wild-type and skn-1 mutant worms survived a parallel control 72-h incubation in M9 alone (data not shown). (B) Lifespan assay. Worms were maintained at 20°C and scored for survival at the indicated time after the L4 stage. An average of three consecutive experiments involving 25-28 worms each is plotted (Table 4).

Numerous correlations between oxidative stress resistance and longevity have been described (Finkel and Holbrook 2000; Finch and Ruvkun 2001; Dillin et al. 2002; Hekimi and Guarente 2003; Holzenberger et al. 2003). Administration of superoxide dismutase mimetics increases C. elegans lifespan by -40% (Melov et al. 2000). Insulin/IGF-1-like signaling reduces C. elegans lifespan by inhibiting the Foxo-type transcription factor DAF-16, which promotes longevity in part by increasing expression of ROS-resistance genes (Kenyon et al. 1993; Honda and Honda 1999; Finch and Ruvkun 2001; Henderson and Johnson 2001; Lee et al. 2003). Given these precedents, we examined whether skn-1 homozygotes live as long as wild type. Both the mean and maximum lifespans of skn-1(zu67) and skn-1(zu129) homozygotes were reduced by 25%-30% (Fig. 6B; Table 4), indicating that SKN-1 is required for normal longevity.

Table 4.

Reduced lifespan of skn-1 mutants

| Genotype | Mean lifespan ± SD (days) (% wild-type) | Maximum lifespan (days) (% wild-type) | Mean maximum lifespan + SD (days) (% wild-type) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wild type (N2) | 15.9 ± 2.2 (100) | 28 (100) | 24.3 ± 3.5 (100) |

| skn-1 (zu67) | 11.8 ± 1.4 (74) | 17 (61) | 16.3 ± 0.6 (67) |

| skn-1 (zu129) | 11.1 ± 0.1 (70) | 19 (68) | 18.7 ± 0.6 (77) |

Lifespan data are taken from the three experiments that are averaged in the plot shown in Figure 6B. Maximum lifespan refers to the longest lifespan observed in any of the three experiments. Mean maximum lifespan refers to the mean among the maxima for these experiments. S.D., standard deviation.

Discussion

A conserved postembryonic function for SKN-1 in oxidative stress resistance

We have determined that the C. elegans developmental specification protein SKN-1 also mediates a conserved response to oxidative stress. SKN-1 functions similarly to bZIP proteins that regulate Phase II detoxification genes in vertebrates (Nrf1, Nrf2) and yeast (Yap1p, Pap1p). SKN-1 activates a conserved Phase II gene in the intestine and ASI neurons (Figs. 2, 3, 5), SKN-1-binding sites flank C. elegans orthologs of additional Nrf target genes (Table 1), and skn-1 mutants are sensitive to oxidative stress (Fig. 6A). The accumulation of SKN-1 in intestinal nuclei in response to oxidative stress (Fig. 5G; Table 3) may parallel nuclear accumulation of Nrf proteins, Yap1p, and Pap1p, under these conditions (Itoh et al. 1999; Toone et al. 2001; Delaunay et al. 2002). It is possible that the intestinal abnormalities in skn-1(zu67)/nDf41 larvae (Bowerman et al. 1992) involve oxidative stress, because 10%-20% of gcs-1(RNAi) animals also die as larvae with abnormal intestines (data not shown).

These parallels between SKN-1 and Nrf proteins are surprising because the mechanism through which SKN-1 binds DNA is both unique and highly divergent (Blackwell et al. 1994). SKN-1 and Nrf proteins are most similar within the 14-amino-acid DIDLID transactivation element (Fig. 1B; Walker et al. 2000), which appears to be present only in SKN-1 and Nrf protein orthologs, suggesting that in metazoans, preservation of this element has been of critical importance for this oxidative stress response. It will now be of interest to determine whether an uncharacterized C. elegans gene that is closely related to skn-1 (Bowerman et al. 1993) might also be involved in oxidative stress resistance. Here we have studied the originally described skn-1 gene, which rescues the maternal skn-1 defect (Bowerman et al. 1992). In addition to this full-length SKN-1 species, sequence databases predict the existence of two other SKN-1 forms. One of these includes 90 additional N-terminal residues, and the other consists primarily of the 234 C-terminal SKN-1 residues (data not shown). It will be interesting to determine whether these SKN-1 forms respond to oxidative stress. Our findings also raise the intriguing question of whether Nrf proteins and SKN-1 might have similar developmental functions. Nrf2-/- mice are viable, but Nrf1 knockouts caused either an erythroid defect, or abnormal gastrulation and lack of mesoderm (Farmer et al. 1997; Itoh et al. 1997; Chan et al. 1998). The latter phenotype is reminiscent of the maternal skn-1 defect. To determine whether Nrf1 and Nrf2 have redundant developmental functions, it will be necessary to disrupt these genes simultaneously.

Although gcs-1 expression in the intestine is induced by SKN-1 in response to stress, the presence of nuclear SKN-1 allows gcs-1 to be expressed constitutively in the ASI neurons, and gcs-1 expression is skn-1-independent in the pharynx (Fig. 2). In metazoans, Phase II genes thus can be activated through distinct pathways that may be important for functions of different tissues. For example, the finding that skn-1 functions constitutively in the ASI neurons, which inhibit dauer entry, suggests that although skn-1(zu67) homozygotes can enter the dauer stage (data not shown), skn-1 or oxidative stress might influence regulation of this process.

The lifespan reduction that we observed in skn-1 mutants (25%-30%; Fig. 6B; Table 4) is comparable to that reported in daf-16 mutants (20%; Kenyon et al. 1993; Lee et al. 2001). In C. elegans, aging involves pleiotropic changes that vary among individuals, and mutations that influence lifespan may affect aging of some tissues more than others (Garigan et al. 2002; Herndon et al. 2002). Just before death, the anterior intestine and posterior pharynx degenerated more frequently in skn-1 animals than wild type (data not shown), a finding that may reflect aging but does not exclude the possibility of an additional defect. At 1 wk after hatching, small cavities and apparent yolk droplets appeared in the heads of many skn-1 but not wild-type animals (data not shown). These changes are typical of aging C. elegans (Garigan et al. 2002; Herndon et al. 2002), suggesting that skn-1 mutants may age prematurely. Some mechanisms that regulate C. elegans lifespan have been shown to influence lifespan in higher metazoans (Clancy et al. 2001; Finch and Ruvkun 2001; Bluher et al. 2003; Holzenberger et al. 2003). The observation that normal C. elegans longevity requires skn-1 is consistent with other associations between oxidative stress resistance and lifespan (see Results), and suggests that the conserved oxidative-stress-resistance pathway regulated by SKN-1 might influence longevity in other species.

Oxidative stress contributes to human pathologies that include diabetes, atherosclerosis, neurodegenerative diseases, reperfusion injury, and HIV infection (Finkel and Holbrook 2000; Droge 2002). The ROS defenses mobilized by human Nrf proteins are thought to be beneficial in those diverse disease states. This gene activation pathway is also important for drug detoxification, and therefore for chemotherapeutic agent tolerance, and it may provide a widely applicable means of cancer prevention (Chan et al. 2001; Hayes and McMahon 2001; Wolf 2001). For example, dietary consumption of chemoprotective antioxidants acts through Nrf2 to inhibit chemical carcinogenesis in mice, and decreases the risk of gastrointestinal and lung tumors in humans (Ramos-Gomez et al. 2001; Fahey et al. 2002; Thimmulappa et al. 2002). The functional parallels between SKN-1 and Nrf proteins indicate that it may be possible to derive novel therapeutic modalities and targets by investigating this detoxification system in C. elegans, a metazoan that is highly amenable to genetic and pharmacologic screening.

Mesendoderm specification by an oxidative stress response factor

It is striking that SKN-1 initiates embryonic development of the mesendoderm, then is critical for one of the most basic functions of endodermal organs, ROS detoxification. Some organs are induced to develop by transcription factors that later regulate downstream differentiation genes (Gehring and Ikeo 1999; Gaudet and Mango 2002). SKN-1 represents an extreme example of a connection between development and function because it initiates formation of multiple organs, including the entire feeding and digestive system. The remarkable functional conservation among SKN-1, Nrf proteins, and their yeast counterparts suggest that this oxidative stress response function of SKN-1 is ancient, and presumably predates its developmental role in mesendoderm specification. The digestive system handles energy intake and processing, and responses to external stresses. Mesodermal tissues that are developmentally linked to the endoderm, the C. elegans pharynx and the vertebrate heart and hematopoietic system, are also involved in nutrient intake and transfer and responses to exogenous agents. SKN-1 may have been co-opted for a fate specification role after these organs evolved. On the other hand, the mesendoderm itself might have arisen as a tissue set that was functionally linked to these ancestral detoxification mechanisms.

Materials and methods

C. elegans strains and bioinformatics

Strains were maintained at 20°C unless otherwise noted, using standard methods (Brenner 1974). The alleles used were N2 Bristol as the wild type, and skn-1(zu67) and skn-1(zu129) (Bowerman et al. 1992). C. elegans orthologs of Nrf targets and other detoxification genes were identified by searching WORMpep or genomic databases (Sanger Centre). Predicted SKN-1 sites (Fig. 1C) 5′ of their coding regions were identified with TFSEARCH (Heinemeyer et al. 1998).

Paraquat sensitivity and lifespan assays

To assay sensitivity to paraquat, young adults were transferred from NGM agar plates into 24-well plates (6 per well) containing 0.3 μL of M9 that either did or did not contain 100 mM paraquat. Worms were incubated at 20°C, and the number of dead animals was counted by the continuous absence of swimming movements and pharyngeal pumping. Lifespan assays were performed essentially as described by Hsin and Kenyon (1999). Animals were transferred to new plates daily and classified as dead when they did not move after repeated prodding with a pick. Animals that crawled away from the plate, exploded, or contained internally hatched worms were excluded from the analysis.

Plasmid constructions

All PCR was performed using Pfu polymerase (Stratagene). GFP vectors pPD95.67 and pPD114.35 were gifts from Andrew Fire (Carnegie Institute of Washington, Baltimore, MD). We created an skn-1::gfp promoter fusion construct (SknPro::GFP; Fig. 5A) by ligating GFP vector pPD95.67 and a PCR-amplified 2.1-kb clone containing the promoter region and 38 amino acids from the first ATG codon of the skn-1 gene from cosmid T19E7. To generate the SKN-1::GFP translational fusion construct (Fig. 5A), the 5.7-kb EcoRI DNA fragment that rescues the maternal skn-1 phenotype and encodes the 533-amino-acid SKN-1 protein (Bowerman et al. 1992) was amplified from cosmid B0547. A ClaI site was created immediately 3′ to the SKN-1 C terminus by the QuikChange method (Stratagene), which was used for all site-directed mutagenesis. This EcoRI fragment was subcloned into pUC18, which contained the upstream 1.3-kb SphI-EcoRI fragment from SknPro::GFP (Fig. 5A). A 0.8-kb ClaI fragment that contained the GFP open reading frame (amplified from plasmid pPD114.35) was then cloned into the ClaI site to generate an in-frame exon fusion of GFP to the SKN-1 C terminus.

The C. elegans gcs-1 ORF (F37B12.2) is between 45% and 54% identical to human, mouse, Drosophila, and yeast GCS(h) (data not shown). To construct the gcs-1::gfp transgene, a fragment that contained 1840 bp upstream of the initiation ATG, along with sequences encoding the 17 N-terminal GCS-1 residues, was amplified by PCR from cosmid F37B12, and cloned into GFP vector pPD95.67. Promoter deletions were similarly constructed by PCR. In gcs-1 point mutation constructs, predicted SKN-1 sites (underlined) were altered as follows: Site 1, -608 GATGACAAT to CTGCAGAAT; Site 2, -317 GAT GACTTA to CTGCAGTTA; and Site 3, -121 TTTATCATC to TTTCTGCAG.

Transgenic analyses

Transgenic strains were generated by injecting DNA into the gonad of young adult animals as described (Mello et al. 1991). gcs-1::gfp transgene constructs (Fig. 3A) were injected at 50 ng/μL along with the rol-6 marker (pRF4) at 100 ng/μL. Between three and six independent extrachromosomal lines were generated and analyzed for each gcs-1::gfp construct. To investigate GCS-1::GFP expression in the skn-1(zu67) background, rol-6-marked gcs-1::gfp hermaphrodites were mated with N2 males; then their transgenic progeny were crossed with skn-1(zu67)/DnT1 hermaphrodites, which have an unc phenotype. After transgenic males were successively crossed twice with skn-1(zu67)/DnT1 hermaphrodites, unc; rol F3 hermaphrodite progeny were selected. From this population, skn-1(zu67)/DnT1; gcs-1::gfp animals were identified on the basis of their non-unc; rol progeny laying dead eggs. Two different gcs-1::gfp lines were thereby crossed into the skn-1(zu67) background and examined for GFP expression. DIC and fluorescence images were acquired with a Zeiss AxioSKOP2 microscope and AxioCam cooled color digital camera.

To investigate expression of gcs-1::gfp and mutant transgenes, worms were exposed to oxidative stress under the following conditions. For heat shock, worms cultured at 20°C were transferred onto prewarmed seeded plates and incubated at 29°C for 20 h, then examined by fluorescence microscopy for GFP expression. gcs-1::gfp induction was also observed in an alternative heat treatment protocol, during which worms cultured at 20°C were transferred onto prewarmed plates and incubated at 34°C for 2-4 h, then returned to 20°C and examined for GFP expression hourly during a 4-h recovery period. In the experiments described in Table 2, young adults were transferred to plates that contained 1 mM paraquat in the agar and maintained at 20°C for 3 d prior to analysis. In an alternative induction protocol, worms that carried gcs-1::gfp or the mutant transgenes shown in Figure 3A were incubated in M9 either with or without 100 mM paraquat for 30 min, then allowed to recover on plates for 4 h. The latter procedure also resulted in induction of intestinal gcs-1::gfp expression by paraquat but was associated with a higher background in uninduced animals.

To create transgenic skn-1::gfp strains, 2.5, 10, or 50 ng/μL of transgene DNA (Fig. 5A) was injected into N2 animals along with 100 ng/μL of pRF4 to generate extrachromosomal transgenic lines. Two different extrachromosomal arrays, Ex001 and Ex007, generated with 2.5and 10 ng/μL of SKN-1::GFP, respectively, were integrated into the chromosome by UV irradiation (400 J/m2) to produce the insertion strains Is001 and Is007, respectively. To rescue the embryonic lethality of an skn-1 mutation, SKN-1::GFP was injected into skn-1(zu67)/DnT1 animals at 2.5ng/μL with 100 ng/μL of the pRF4 marker. Rescue of maternal skn-1 lethality was observed in some rol; non-unc progeny but not in non-rol; non-unc animals.

SKN-1::GFP expression analyses shown were performed in the Is007 strain, but essentially the same results were obtained in analyses of Ex001, Ex007, and Is001 (data not shown). To analyze expression and localization of SKN-1::GFP in response to oxidative stress, skn-1::gfp transgenic worms were treated as described above for the gcs-1::gfp expression studies. In addition, for exposure to sodium azide, animals cultured at 20°C were placed on a 2% agarose pad on a slide in M9 either with or without 50 mM sodium azide, then covered with a slip and examined by fluorescence microscopy. These worms were scored for the presence of SKN-1::GFP in intestinal nuclei 5 min later. For photography, worms were immobilized with either 2 mM sodium azide (Figs. 2, 3) or 2 mM levamisole (Fig. 5). These treatments did not stimulate either GCS-1::GFP induction or SKN-1::GFP relocalization during the times examined (data not shown). No immobilization agent was used in the experiments shown in Tables 2 and 3. To discriminate intestinal autofluorescence from SKN-1::GFP epifluorescence, a triple-band emission filter set (Chroma 61000) was used in conjunction with a narrow-band excitation filter (484/14 nm). This combination allowed autofluorescence to be detected as yellow/orange fluorescence deriving from a combined green and red signal, while GFP remained green.

Worms that carried skn-1::gfp, gcs-1::gfp, and gcs-1::gfp mutant transgenes were incubated with 50 μg/mL DiI (Molecular Probes) in M9 at 20°C for 3 h, then transferred to fresh plates for 1 h to destain, and examined under the fluorescence microscope. The ASI chemosensory neurons were identified by according to their intensity of DiI labeling and location relative to other DiI-labeled cells.

DNA-binding assays

Full-length SKN-1 and the SKN domain were expressed by in vitro translation (Promega) as described previously (Carroll et al. 1997). Oligonucleotide probes were end-labeled using Klenow and α-32P-labeled dATP and CTP, then purified using QIAquick Kit (QIAGEN). EMSAs were performed essentially as described in (Blackwell et al. 1994), with labeled probes present at 2.5× 10-9 M.

Acknowledgments

We thank Bruce Bowerman, Grace Gill, Yang Shi, Siu Sylvia Lee, Kaveh Ashrafi, Elizabeth Veal, and Blackwell lab members for helpful discussions, technical advice, or critical reading of this manuscript. For reagents we thank Andrew Fire, Alan Coulson, Yuji Kohara, and the Caenorhabditis genetics center. We thank Courtney DiPaolo for technical assistance, and are particularly grateful to Amy Walker for contributions to early stages of this project. This work was supported by a grant from the NIH to T.K.B. (GM62891).

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by payment of page charges. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

Corresponding author.

Article published online ahead of print. Article and publication date are at http://www.genesdev.org/cgi/doi/10.1101/gad.1107803.

References

- Blackwell T.K., Bowerman, B., Priess, J., and Weintraub, H. 1994. Formation of a monomeric DNA binding domain by Skn-1 bZIP and homeodomain elements. Science 266: 621-628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bluher M., Kahn, B.B., and Kahn, C.R. 2003. Extended longevity in mice lacking the insulin receptor in adipose tissue. Science 299: 572-574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowerman B., Eaton, B.A., and Priess, J.R. 1992. skn-1, a maternally expressed gene required to specify the fate of ventral blastomeres in the early C. elegans embryo. Cell 68: 1061-1075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowerman B., Draper, B.W., Mello, C., and Priess, J. 1993. The maternal gene skn-1 encodes a protein that is distributed unequally in early C. elegans embryos. Cell 74: 443-452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brenner S. 1974. The genetics of Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics 77: 71-94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll A.S., Gilbert, D.E., Liu, X., Cheung, J.W., Michnowicz, J.E., Wagner, G., Ellenberger, T.E., and Blackwell, T.K. 1997. SKN-1 domain folding and basic region monomer stabilization upon DNA binding. Genes & Dev. 11: 2227-2238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan J.Y., Kwong, M., Lu, R., Chang, J., Wang, B., Yen, T.S., and Kan, Y.W. 1998. Targeted disruption of the ubiquitous CNC-bZIP transcription factor, Nrf-1, results in anemia and embryonic lethality in mice. EMBO J. 17: 1779-1787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan K. and Kan, Y.W. 1999. Nrf2 is essential for protection against acute pulmonary injury in mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 96: 12731-12736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan K., Han, X.D., and Kan, Y.W. 2001. An important function of Nrf2 in combating oxidative stress: Detoxification of acetaminophen. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 98: 4611-4616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clancy D.J., Gems, D., Harshman, L.G., Oldham, S., Stocker, H., Hafen, E., Leevers, S.J., and Partridge, L. 2001. Extension of life-span by loss of CHICO, a Drosophila insulin receptor substrate protein. Science 292: 104-106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delaunay A., Pflieger, D., Barrault, M.B., Vinh, J., and Toledano, M.B. 2002. A thiol peroxidase is an H2O2 receptor and redox-transducer in gene activation. Cell 111: 471-481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dillin A., Crawford, D.K., and Kenyon, C. 2002. Timing requirements for insulin/IGF-1 signaling in C. elegans. Science 298: 830-834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Droge W. 2002. Free radicals in the physiological control of cell function. Physiol. Rev. 82: 47-95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fahey J.W., Haristoy, X., Dolan, P.M., Kensler, T.W., Scholtus, I., Stephenson, K.K., Talalay, P., and Lozniewski, A. 2002. Sulforaphane inhibits extracellular, intracellular, and antibiotic-resistant strains of Helicobacter pylori and prevents benzo[a]pyrene-induced stomach tumors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 99: 7610-7615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farmer S.C., Sun, C.W., Winnier, G.E., Hogan, B.L., and Townes, T.M. 1997. The bZIP transcription factor LCR-F1 is essential for mesoderm formation in mouse development. Genes & Dev. 11: 786-798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finch C.E. and Ruvkun, G. 2001. The genetics of aging. Annu. Rev. Genomics Hum. Genet. 2: 435-462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finkel T. and Holbrook, N.J. 2000. Oxidants, oxidative stress and the biology of ageing. Nature 408: 239-247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garigan D., Hsu, A.L., Fraser, A.G., Kamath, R.S., Ahringer, J., and Kenyon, C. 2002. Genetic analysis of tissue aging in Caenorhabditis elegans. A role for heat-shock factor and bacterial proliferation. Genetics 161: 1101-1112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaudet J. and Mango, S.E. 2002. Regulation of organogenesis by the Caenorhabditis elegans FoxA protein PHA-4. Science 295: 821-825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gehring W.J. and Ikeo, K. 1999. Pax 6: Mastering eye morphogenesis and eye evolution. Trends Genet. 15: 371-377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haun C., Alexander, J., Stainier, D.Y., and Okkema, P.G. 1998. Rescue of Caenorhabditis elegans pharyngeal development by a vertebrate heart specification gene. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 95: 5072-5075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes J.D. and McMahon, M. 2001. Molecular basis for the contribution of the antioxidant responsive element to cancer chemoprevention. Cancer Lett. 174: 103-113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heinemeyer T., Wingender, E., Reuter, I., Hermjakob, H., Kel, A.E., Kel, O.V., Ignatieva, E.V., Ananko, E.A., Podkolodnaya, O.A., Kolpakov, F.A., et al. 1998. Databases on transcriptional regulation: TRANSFAC, TRRD and COMPEL. Nucleic Acids Res. 26: 362-367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hekimi S. and Guarente, L. 2003. Genetics and the specificity of the aging process. Science 299: 1351-1354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henderson S.T. and Johnson, T.E. 2001. daf-16 integrates developmental and environmental inputs to mediate aging in the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans. Curr. Biol. 11: 1975-1980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herman R.K. and Hedgecock, E.M. 1990. Limitation of the size of the vulval primordium of Caenorhabditis elegans by lin-15 expression in surrounding hypodermis. Nature 348: 169-171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herndon L.A., Schmeissner, P.J., Dudaronek, J.M., Brown, P.A., Listner, K.M., Sakano, Y., Paupard, M.C., Hall, D.H., and Driscoll, M. 2002. Stochastic and genetic factors influence tissue-specific decline in ageing C. elegans. Nature 419: 808-814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holzenberger M., Dupont, J., Ducos, B., Leneuve, P., Geloen, A., Even, P.C., Cervera, P., and Le Bouc, Y. 2003. IGF-1 receptor regulates lifespan and resistance to oxidative stress in mice. Nature 421: 182-187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Honda Y. and Honda, S. 1999. The daf-2 gene network for longevity regulates oxidative stress resistance and Mn-superoxide dismutase gene expression in Caenorhabditis elegans. FASEB J. 13: 1385-1393. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsin H. and Kenyon, C. 1999. Signals from the reproductive system regulate the lifespan of C. elegans. Nature 399: 362-366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Itoh K., Chiba, T., Takahashi, S., Ishii, T., Igarashi, K., Katoh, Y., Oyake, T., Hayashi, N., Satoh, K., Hatayama, I., et al. 1997. An Nrf2/small Maf heterodimer mediates the induction of phase II detoxifying enzyme genes through antioxidant response elements. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 236: 313-322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Itoh K., Wakabayashi, N., Katoh, Y., Ishii, T., Igarashi, K., Engel, J.D., and Yamamoto, M. 1999. Keap1 represses nuclear activation of antioxidant responsive elements by Nrf2 through binding to the amino-terminal Neh2 domain. Genes & Dev. 13: 76-86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly W.G., Xu, S., Montgomery, M.K., and Fire, A. 1997. Distinct requirements for somatic and germline expression of a generally expressed Caenorhabditis elegans gene. Genetics 146: 227-238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenyon C., Chang, J., Gensch, E., Rudner, A., and Tabtiang, R. 1993. A C. elegans mutant that lives twice as long as wild type. Nature 366: 461-464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kophengnavong T., Carroll, A.S., and Blackwell, T.K. 1999. The SKN-1 amino terminal arm is a DNA specificity segment. Mol. Cell Biol. 19: 3039-3050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee R.Y., Hench, J., and Ruvkun, G. 2001. Regulation of C. elegans DAF-16 and its human ortholog FKHRL1 by the daf-2 insulin-like signaling pathway. Curr. Biol. 11: 1950-1957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee S.S., Kennedy, S., Tolonen, A.C., and Ruvkun, G. 2003. DAF-16 target genes that control C. elegans life-span and metabolism. Science 300: 644-647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lickert H., Kutsch, S., Kanzler, B., Tamai, Y., Taketo, M.M., and Kemler, R. 2002. Formation of multiple hearts in mice following deletion of β-catenin in the embryonic endoderm. Dev. Cell 3: 171-181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maduro M.F. and Rothman, J.H. 2002. Making worm guts: The gene regulatory network of the Caenorhabditis elegans endoderm. Dev. Biol. 246: 68-85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maduro M.F., Meneghini, M.D., Bowerman, B., Broitman-Maduro, G., and Rothman, J.H. 2001. Restriction of mesendoderm to a single blastomere by the combined action of SKN-1 and a GSK-3β homolog is mediated by MED-1 and -2 in C. elegans. Mol. Cell 7: 475-485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mello C.C., Kramer, J.M., Stinchcomb, D., and Ambros, V. 1991. Efficient gene transfer in C. elegans: Extrachromosomal maintenance and integration of transforming sequences. EMBO J. 10: 3959-3970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melov S., Ravenscroft, J., Malik, S., Gill, M.S., Walker, D.W., Clayton, P.E., Wallace, D.C., Malfroy, B., Doctrow, S.R., and Lithgow, G.J. 2000. Extension of life-span with superoxide dismutase/catalase mimetics. Science 289: 1567-1569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen T., Sherratt, P.J., Huang, H.C., Yang, C.S., and Pickett, C.B. 2003. Increased protein stability as a mechanism that enhances Nrf2-mediated transcriptional activation of the antioxidant response element. Degradation of Nrf2 by the 26 S proteasome. J. Biol. Chem. 278: 4536-4541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramos-Gomez M., Kwak, M.K., Dolan, P.M., Itoh, K., Yamamoto, M., Talalay, P., and Kensler, T.W. 2001. Sensitivity to carcinogenesis is increased and chemoprotective efficacy of enzyme inducers is lost in nrf2 transcription factor-deficient mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 98: 3410-3415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reiter J.F., Alexander, J., Rodaway, A., Yelon, D., Patient, R., Holder, N., and Stainier, D.Y. 1999. Gata5is required for the development of the heart and endoderm in zebrafish. Genes & Dev. 13: 2983-2995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ren P., Lim, C.S., Johnsen, R., Albert, P.S., Pilgrim, D., and Riddle, D.L. 1996. Control of C. elegans larval development by neuronal expression of a TGF-β homolog. Science 274: 1389-1391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodaway A. and Patient, R. 2001. Mesendoderm. An ancient germ layer? Cell 105: 169-172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schackwitz W.S., Inoue, T., and Thomas, J.H. 1996. Chemosensory neurons function in parallel to mediate a pheromone response in C. elegans. Neuron 17: 719-728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sekhar K.R., Yan, X.X., and Freeman, M.L. 2002. Nrf2 degradation by the ubiquitin proteasome pathway is inhibited by KIAA0132, the human homolog to INrf2. Oncogene 21: 6829-6834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shoichet S.A., Malik, T.H., Rothman, J.H., and Shivdasani, R.A. 2000. Action of the Caenorhabditis elegans GATA factor END-1 in Xenopus suggests that similar mechanisms initiate endoderm development in ecdysozoa and vertebrates. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 97: 4076-4081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart D., Killeen, E., Naquin, R., Alam, S., and Alam, J. 2003. Degradation of transcription factor Nrf2 via the ubiquitinproteasome pathway and stabilization by cadmium. J. Biol. Chem. 278: 2396-2402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Talanian R.V., McKnight, C.J., and Kim, P.S. 1990. Sequence-specific DNA binding by a short peptide dimer. Science 249: 769-771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thatcher J.D., Fernandez, A.P., Beaster-Jones, L., Haun, C., and Okkema, P.G. 2001. The Caenorhabditis elegans peb-1 gene encodes a novel DNA-binding protein involved in morphogenesis of the pharynx, vulva, and hindgut. Dev. Biol. 229: 480-493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thimmulappa R.K., Mai, K.H., Srisuma, S., Kensler, T.W., Yamamoto, M., and Biswal, S. 2002. Identification of Nrf2-regulated genes induced by the chemopreventive agent sulforaphane by oligonucleotide microarray. Cancer Res. 62: 5196-5203. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toone W.M. and Jones, N. 1999. AP-1 transcription factors in yeast. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 9: 55-61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toone W.M., Morgan, B.A., and Jones, N. 2001. Redox control of AP-1-like factors in yeast and beyond. Oncogene 20: 2336-2346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker A.K., See, R., Batchelder, C., Kophengnavong, T., Gronniger, J.T., Shi, Y., and Blackwell, T.K. 2000. A conserved transcription motif suggesting functional parallels between C. elegans SKN-1 and Cap 'n' Collar-related bZIP proteins. J. Biol. Chem. 275: 22166-22171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warga R.M. and Nusslein-Volhard, C. 1999. Origin and development of the zebrafish endoderm. Development 126: 827-838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolf C.R. 2001. Chemoprevention: Increased potential to bear fruit. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 98: 2941-2943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]