Abstract

Spen proteins regulate the expression of key transcriptional effectors in diverse signaling pathways. They are large proteins characterized by N-terminal RNA-binding motifs and a highly conserved C-terminal SPOC domain. The specific biological role of the SPOC domain (Spen paralog and ortholog C-terminal domain), and hence, the common function of Spen proteins, has been unclear to date. The Spen protein, SHARP (SMRT/HDAC1-associated repressor protein), was identified as a component of transcriptional repression complexes in both nuclear receptor and Notch/RBP-Jκ signaling pathways. We have determined the 1.8 Å crystal structure of the SPOC domain from SHARP. This structure shows that essentially all of the conserved surface residues map to a positively charged patch. Structure-based mutational analysis indicates that this conserved region is responsible for the interaction between SHARP and the universal transcriptional corepressor SMRT/NCoR (silencing mediator for retinoid and thyroid receptors/nuclear receptor corepressor. We demonstrate that this interaction involves a highly conserved acidic motif at the C terminus of SMRT/NCoR. These findings suggest that the conserved function of the SPOC domain is to mediate interaction with SMRT/NCoR corepressors, and that Spen proteins play an essential role in the repression complex.

Keywords: SHARP, SPOC domain, Spen proteins, transcriptional corepressor, crystal structure, nuclear receptor

The split ends (spen) gene was first identified as a recessive lethal mutation perturbing lateral chordotonal axons in the abdominal segments of Drosophila embryos (Kolodziej et al. 1995). It has subsequently become clear that Spen and related proteins play a general role in cell-fate specification during development (Chen and Rebay 2000; Kuang et al. 2000; Rebay et al. 2000). Cell fate is specified by a complex interplay between signaling pathways and transcription factors (Jan and Jan 1994; Lee and Pfaff 2001; Schuurmans and Guillemot 2002) and is fundamental to development, cellular differentiation, proliferation, and patterning of highly organized tissues (Bertrand et al. 2002). In the Drosophila embryo, mutations in spen have been shown to affect cell-fate specification through perturbation of the Notch, epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR), and Ras/MAP kinase signaling pathways. Genetic studies have suggested that the spen mutations result in aberrant expression of the transcriptional repressors Suppressor of Hairless, and Yan, which are required for Notch and EGFR signaling, respectively (Kuang et al. 2000; Rebay et al. 2000).

Spen proteins have been identified in worms, flies, and vertebrates and appear to play a similar role in each organism. In mice, the MINT (Msx2 interacting nuclear target) protein is involved in skeletal and neuronal development by mediating repression by the homeodomain transcriptional repressor Msx2 (Newberry et al. 1999). The human homolog of MINT, SHARP (SMRT/HDAC1-associated repressor protein), has been identified as a component in transcriptional repression complexes recruited by both nuclear receptors and the Notch-signaling factor RBP-Jκ (Shi et al. 2001; Oswald et al. 2002). The importance of the Spen protein family is emphasized by the finding that a Spen protein, the chromosome 1 gene product, one twenty two, OTT (also known as RNA-binding motif protein 15, RBM15) is involved in the recurrent t(1;22)(p13;q13) translocation associated with infant acute megakaryocytic leukaemia (Ma et al. 2001; Mercher et al. 2001). The resulting fusion protein is thought to aberrantly modulate chromatin organization.

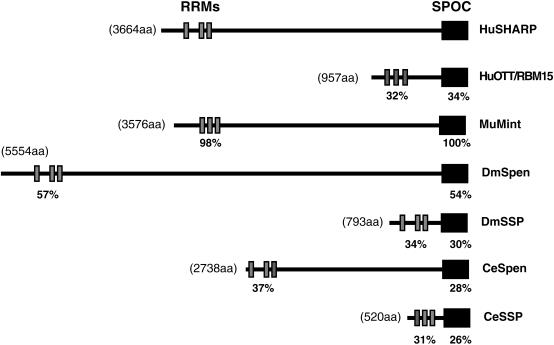

Spen proteins vary widely in size (90-600 kD), but are nevertheless characterized by a conserved domain structure. Three repeated RNA recognition motifs (RRMs) are located near the N terminus, and at the C terminus there is a conserved, so-called SPOC domain (Spen paralog and ortholog C-terminal domain), of ∼165 amino acids (Wiellette et al. 1999; Kuang et al. 2000; Fig. 1). The intervening region between these conserved domains shows poor homology; little evidence of structured domains, and is thought to be responsible for interaction with various transcription factors. The conserved domain structure of Spen proteins suggests that they share a common function and molecular mechanism, although the exact nature of this remains to be elucidated. The RRMs would appear to suggest a role in RNA or DNA binding, whereas no specific function has been attributed to the SPOC domain. However, mutations in the SPOC domain, as well as a C-terminal deletion of the Drosophila Spen protein, suggest that the SPOC domain is essential for normal function (Wiellette et al. 1999; Chen and Rebay 2000).

Figure 1.

Common domain organization of the Spen proteins. HuSHARP, human SHARP; HuOTT, human OTT/RBM15; DmSpen, Drosophila Spen; DmSSP, Drosophila short Spen protein; CeSpen, C. elegans Spen; CeSSP, C. elegans short Spen protein. The approximate locations of RRMs and the SPOC domain of each protein are indicated in gray and black boxes, respectively. The percentages of identical residues in each domain of human OTT, Drosophila, and C. elegans homologs with human SHARP are indicated.

Further insight into the role of Spen proteins was obtained from the finding that SHARP is able to bind to the corepressor proteins SMRT (silencing mediator for retinoid and thyroid receptors) and NCoR (nuclear receptor corepressor; Shi et al. 2001). SMRT and NCoR are required for transcriptional repression by unliganded nuclear receptors (Chen and Evans 1995; Horlein et al. 1995; Kurokawa et al. 1995; Ordentlich et al. 1999) and many other transcription factors including RBP-Jκ (Kao et al. 1998; Glass and Rosenfeld 2000; Zhang et al. 2002). These corepressors, in turn, repress the level of basal transcription by mediating the assembly of a larger multiprotein complex containing histone deacetylase (HDAC) activity (Heinzel et al. 1997; Nagy et al. 1997; Fischle et al. 2002; Zhang et al. 2002; Yoon et al. 2003). Mouse embryos lacking NCoR exhibit defects in the development of erythrocytic, thymic, and neural systems (Jepsen et al. 2000; Hermanson et al. 2002). These findings highlight the physiological role of active repression, mediated by SMRT/NCoR, in cell-fate specification during mammalian development.

It is clear, therefore, that SHARP plays a central role in mediating transcriptional repression through nuclear receptors, Notch, and other transcriptional factors. Structural insights into SHARP might not only enhance our understanding of the molecular assembly of the transcriptional repression complex, but might also provide clues to the molecular mechanism of the Spen proteins. Accordingly, we have determined the structure of the SPOC domain from SHARP. A number of absolutely conserved residues lie on the surface of the protein and map to a positively charged region. This is suggestive of an interaction with nucleic acid or a negatively charged protein. We demonstrate that the SPOC domain of SHARP is sufficient for interaction with the negatively charged C terminus of SMRT. Mutations of the conserved surface residues in the SPOC domain abolish this interaction. These findings suggest that the conserved function of the SPOC domain is to mediate interaction with SMRT/NCoR corepressors, and that Spen proteins play an essential role in the repression complex.

Results

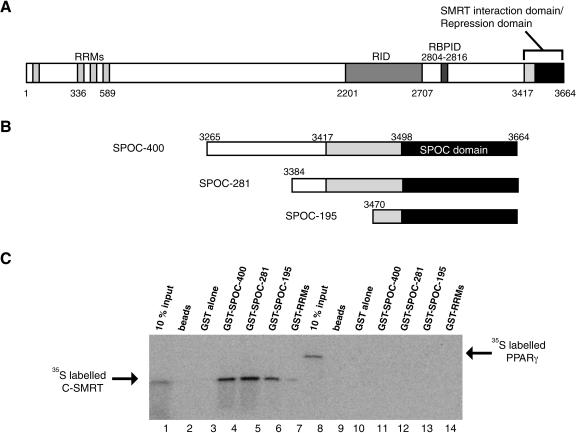

The SPOC domain is sufficient for interaction with SMRT

Previous studies, using a yeast two-hybrid assay, have suggested that the minimal SHARP construct able to interact with the corepressor SMRT encompasses the C-terminal amino acids 3417-3664 (Shi et al. 2001). This region comprises the conserved SPOC domain (amino acids 3498-3664) with an 81 residue N-terminal extension (Fig. 2A). Further truncation of this fragment appeared to significantly reduce the interaction with SMRT. Fragments of SHARP, containing the SPOC domain with different N-terminal extensions, were expressed in Escherichia coli, with an N-terminal affinity tag, for structural and functional studies (Fig. 2B). Limited proteolysis, following purification and tag removal, revealed a protease-resistant domain corresponding to the size of the SPOC domain, suggesting that, at least in the absence of SMRT, the N-terminal extension may be unstructured (data not shown).

Figure 2.

Functional domains of SHARP. (A) SHARP possesses a nuclear receptor interaction domain (RID) and RBP-Jκ interaction domain (RBPID) as well as RRMs and the SPOC domain. The C-terminal region of SHARP (amino acids 3417-3664), containing the SPOC domain, was characterized previously as a SMRT interaction domain or repression domain (Shi et al. 2001). (B) The recombinant C-terminal fragments of SHARP are shown schematically. The SPOC domain (amino acids 3498-3664) is represented by a black box. (C) The SPOC domain of SHARP interacts with C-SMRT. 35S-labeled in vitro translated C-SMRT (amino acids 2257-2517; lanes 1-7) and the N-terminal domain of PPARγ2 (amino acids 1-138; lanes 8-14) were incubated with purified GST or GST-SHARP fragments on glutathione beads. The bound proteins were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and visualized by fluorography. Note, there is a weak interaction between C-SMRT and the GST-RRMs. This is far weaker than the interaction with the GST-SPOC domain and seems unlikely to be biologically relevant.

To test whether the SHARP fragments are able to interact with SMRT, we used a pull-down assay to measure the interaction between bacterially expressed glutathione-S-transferase (GST)-tagged SHARP and [35S]methionine SMRT (amino acids 2257-2517) prepared using in vitro transcription/translation methods. The experiment showed that SMRT was able to interact with all three SHARP fragments (Fig. 2C, lanes 4-6). No interaction could be detected with glutathione-Sepharose resin, with GST alone, or with the control RRMs from SHARP (Fig. 2C, lanes 2-3,7). A further specificity control demonstrated that the N-terminal domain of the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ2 (PPARγ2) showed no interaction with the SHARP fragments (Fig. 2C, lanes 11-13).

These findings demonstrate that the SPOC domain itself is sufficient for direct specific interaction with the C-terminal region of SMRT/NCoR.

Structure of the SPOC domain

To gain some insight into the function of the SPOC domain, we sought to crystallize the three fragments of SHARP (Fig. 2B). Only the shortest fragment, termed SPOC-195 (amino acids 3470-3664), yielded diffraction quality crystals. The structure was solved to 1.8 Å resolution using phase information derived from the anomalous scattering of selenium (at three wavelengths) in crystals of seleno-methionine-substituted protein (Table 1). No electron density was observed for the 25 N-terminal residues (amino acids 3470-3494) and three residues (amino acids 3542-3544) in a loop region. SDS-PAGE analysis of dissolved crystals showed that the crystals contain the full-length fragment, suggesting that these regions are disordered (data not shown).

Table 1.

Summary of crystallographic analysis

| Data collection | Native data | MAD data λ1 | λ2 | λ3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wavelength (Å) | 0.978 | 0.97946 | 0.97984 | 0.93939 |

| Resolution (Å) | 30-1.8 (1.84-1.8) | 25-1.8 (1.9-1.8) | 25-1.8 (1.9-1.8) | 25-1.8 (1.9-1.8) |

| Observations | 258,694 | 118,693 | 118,644 | 118,657 |

| Unique reflections | 16,853 | 16,948 | 16,946 | 16,971 |

| Completeness (Å)a | 99.8 (99.8) | 99.7 (99.7) | 99.7 (99.7) | 99.7 (99.7) |

| Rsym (%)ab | 6.8 (8.2) | 7.7 (13.3) | 7.7 (13.3) | 8.3 (11.3) |

| I/σ (I) | 17.1 (5.5) | 4.2 (4.0) | 4.6 (4.5) | 4.0 (3.8) |

| Figure of merit | 0.68 (0.53) | |||

| Refinement statistics | ||||

| Number of atoms (total, water) | 1286, 82 | |||

| Resolution (Å)a | 20-1.8 (1.91-1.8) | |||

| Number of reflections (no sigma cutoff) | 16,731 | |||

| Completeness (%)a | 99.2 (99.2) | |||

| Rcryst (%)ac | 21.4 (20.1) | |||

| Rfree (%)ad | 24.9 (26.3) | |||

| RMSD bond length (Å)c | 0.005 | |||

| RMSD bond angles (°)c | 1.3 |

Numbers in parentheses refer to the highest resolution shells.

Rsym = ∑|I − <I>|o<∑I>, where I is the integrated intensity of a given reflection.

Rcryst = ∑∥Foo| − Fc∥/∑|Fo|.

Rfree was calculated using 10% data extracted from refinement.

The root mean square deviation (RMSD) values in bond lengths and angles are deviations form ideal value.

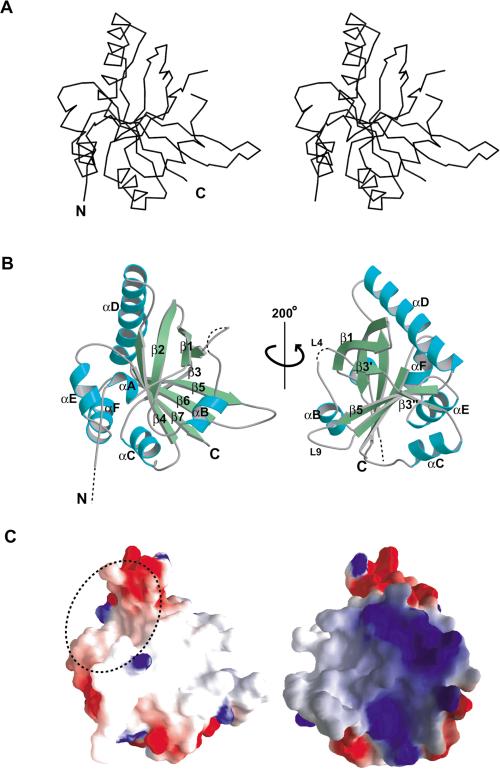

The conserved SPOC domain is folded into a single compact domain ∼40 × 40 × 45 Å3. The domain architecture consists of a β-barrel with seven strands (β1-β7) framed by six α-helices (αA-αF; Fig. 3A,B). One side of the β-barrel is distorted, resulting in a discontinuity in the β3 strand and a disruption of the characteristic pattern of hydrogen bonds between the N-terminal region of β3, β3′, and the adjacent strand, β5. This distortion in the β-barrel results in a clear groove between the β3′ and β5 strands. The inner surface of this groove is nonpolar and surrounded by two proline-rich loops, L4 and L9. It is possible that this region could play a role in protein-protein interactions.

Figure 3.

Structure of the SPOC domain of SHARP. (A) Stereo view of Cα backbone structure of the SPOC domain. (B) Ribbon representation of structure of the SPOC domain (SPOC-195). Broken lines indicate the disordered regions at the N terminus and in the L4 loop (amino acids 3542-3544). The molecule on the right side is rotated by 200° around the vertical axis. (C) Electrostatic surface potential map of the SPOC domain. Red represents regions of negative charge, whereas blue shows positive charges. The molecules are in the same orientation as in B. A dotted circle indicates the hydrophobic and slightly acidic cavity described in text (left). The basic patch is located on the opposite side (right).

There is a second notable cavity or cleft, formed between helices αA, αF, and the N terminus of αD (Fig. 3C, left). The interior surface of this cavity is made up of hydrophobic side chains and backbone carbonyl groups, making it slightly acidic in character. This structural feature is also suggestive of a protein-protein interaction surface.

The surface of the SPOC domain has a strikingly nonuniform charge distribution. The outer surfaces of helices αD (the N-terminal portion) and αE/αF are significantly acidic, and together, make one side of the domain rather negatively charged. In contrast, almost on the opposite side of the domain, on either side of strand β3, the surface is extremely basic with seven lysine/arginine residues (Fig. 3C, right).

Four residues at the N terminus of the SPOC domain (Pro 3495-Met 3498) adopt an extended structure and interact with the β3 strand (Ala 3550-Arg 3554) of an adjacent molecule through a number of main chain hydrogen bonds, forming a β-sheet structure. These residues are within the region predicted to have no secondary structure, and were found to be very sensitive to proteolysis.

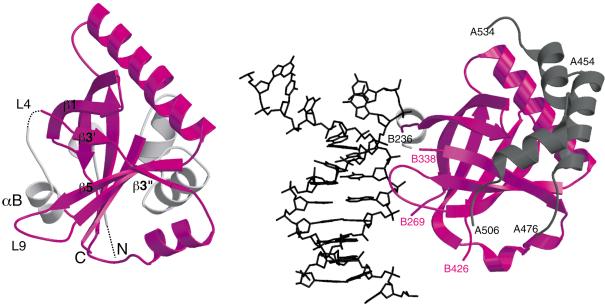

A structural similarity search using DALI (Holm and Sander 1993) indicated that the overall architecture of the SPOC domain resembles the β-barrel domains of the heterodimeric DNA repair protein Ku70:Ku80 (Fig. 4). Despite the low sequence identity (14%-16%), the seven-stranded β-barrel and the helices αC, αD of SPOC-195 superimpose on the corresponding region of Ku80 with a root mean square deviation (r.m.s.d) of 3.6Å over 116 Cα atoms. Comparison of the SPOC domain β-barrel with that of Ku80 is revealing of the distortions in the SPOC β-barrel. It is clear that loop L9 in the SPOC domain is folded out away from the barrel so as to accommodate the αB helix. This leads to the break in the β-sheet between β3′ and β5, resulting in the aforementioned cleft in the surface of the protein. In Ku80, the αB helix is replaced by a long loop that wraps around the DNA in the complex. The equivalent of loop L9 in Ku80 also makes contacts to the DNA. It is very clear that the SPOC domain has an architecture and amino acid distribution that prevents analogous interaction with DNA (Fig. 4, right).

Figure 4.

Structural similarity between the SPOC domain (left) and Ku80 β-barrel domain (PDB, 1jey; right). The structural elements in common are colored in magenta. The Ku80 domain is shown bound to DNA (black), and the three interacting helices from Ku70 are shown in gray. The long peptide loop (B269-B338) in Ku80, which wraps around DNA, is omitted for clarity.

It is important to note that the β-barrel domain in Ku80 is one part of a larger structure and makes multiple protein-protein interactions, including interaction with the heterodimeric partner Ku70 (shown in gray in Fig. 4, right).

Mapping the location of residues conserved in the Spen proteins

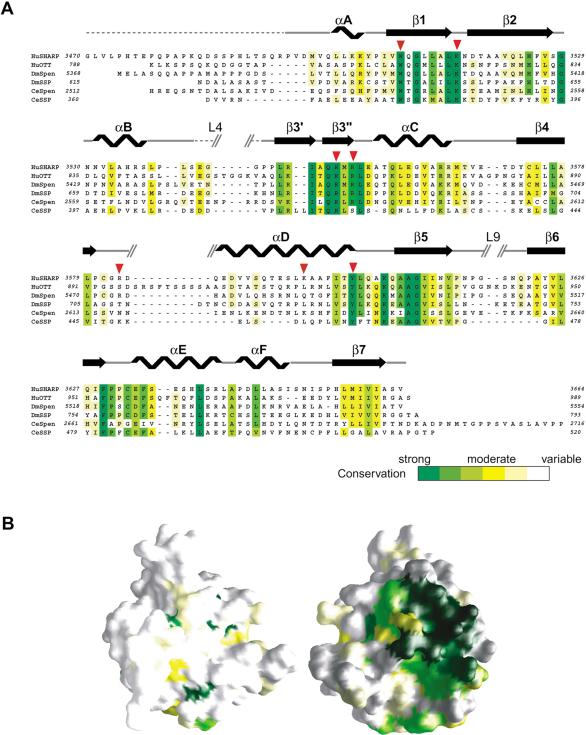

Sequence alignment of the SPOC domain from SHARP with other Spen proteins shows sequence identity ranging from 26% to 54%. Of the residues conserved across the whole family, most lie on the molecular surface rather than in the core (Fig. 5A,B). These conserved surface residues are likely to be revealing of the function of SPOC domain and, therefore, we examined their distribution. Strikingly, the majority of these residues are clustered in one region and include the seven basic residues that form the basic patch discussed earlier (Figs. 3C, 5B). These are Lys 3516, Arg 3548, Arg 3552, Arg 3554, Arg 3565, Arg 3566, and Lys 3606 (Figs. 5A, 7A, below). In addition to the basic residues, a conserved tyrosine residue, Tyr 3602, is situated between Lys 3516 and Lys 3606. Another conserved residue, Trp 3509 also lies within 15-20 Å of the basic cluster. The remarkable conservation of this basic surface is highly suggestive that the common function of the SPOC domain involves recognition of a negatively charged molecule, through stereospecific electrostatic interaction.

Figure 5.

Conservation of the basic cluster in Spen proteins. (A) Sequence conservation in Spen proteins. The sequence of SHARP SPOC domain, SPOC-195, was aligned with those of other spen proteins from human, Drosophila, and C. elegans using CLUSTALW (Thompson et al. 1994). Identical and similar residues are highlighted in a color scheme corresponding to conservation level as shown in the bar at bottom. The secondary structure elements of SPOC-195 are shown above the sequence. The strand β3 is divided into two parts: β3′ and β3′. Broken lines indicate the disordered regions. Red triangles indicate the mutation sites in the peptide interaction assay in Figure 7B. (B) Distribution of the conserved residues mapped on the surface of the SPOC domain. Residues are colored according to conservation as in A. The molecules are represented in the same orientation as in Figure 3. Note that the most conserved region, colored in green (right), corresponds to the basic cluster in Figure 3C.

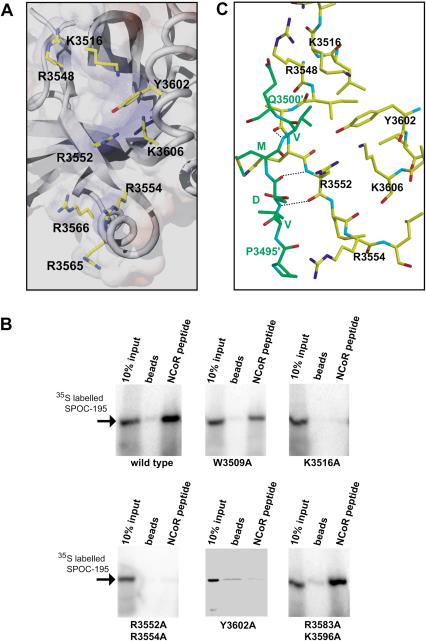

Figure 7.

The conserved basic cluster is essential for interaction with corepressor. (A) A view of the conserved basic region. Key residues are indicated by stick model beneath a semitransparent surface representation. (B) NCoR LSD peptide pull-down assay using wild-type and mutant SPOC domains. Mutation of the conserved tryptophan, W3509A, showed mildly reduced binding to corepressor. Mutations in conserved residues of the SPOC domain (K3516A, R3583A/K3596A, Y3620A) abolish interaction with corepressor. Mutations of nonconserved basic residues (R3583A/K3596A) had no effect. (C) Crystal packing interaction between the N terminus of one SPOC domain (Pro 3495-Gln 3500, in green) with the β3 strand of an adjacent molecule (Arg 3548-Arg 3554, in yellow). This may be indicative of the type of interaction with corepressor peptide. Backbone-backbone hydrogen bonds are indicated by broken lines.

Recognition of the conserved C terminus of SMRT/NCoR by the SPOC domain

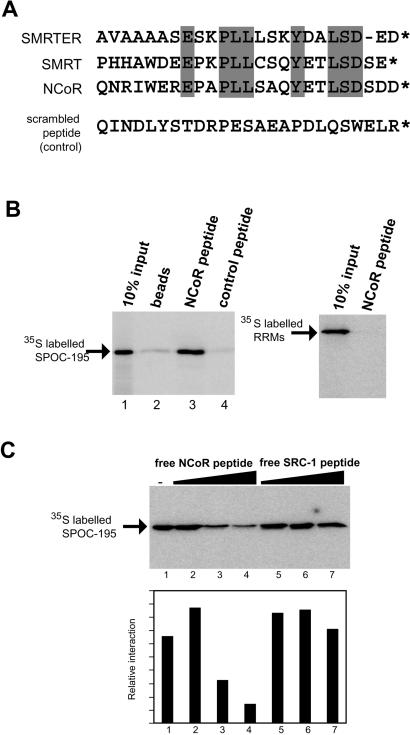

To test whether the conserved basic surface of the SPOC domain might bind to negatively charged nucleic acids, we performed gel mobility shift assays with tRNA and both single and double-stranded DNA. There was no indication of specific or nonspecific interaction, even at protein concentrations as high as 50 μM (data not shown). It seemed likely, therefore, that the basic surface of the SPOC domain is used for protein-protein interactions. Examination of the C terminus of SMRT and NCoR revealed a conserved acidic motif at the very C terminus that has been termed previously the LSD motif (Fig. 6A) and suggested to be important for interaction with SHARP (Shi et al. 2001). To test whether the LSD motif is sufficient for interaction with the SPOC domain of SHARP, we prepared an affinity resin using a 25-residue peptide from the C terminus of NCoR (Fig. 6A). We found that [35S]methionine SPOC domain bound efficiently to this resin (Fig. 6B, lane 3), but not at all to a resin prepared with a control peptide with the same amino acid composition, but in a scrambled order (Fig. 6B, lane 4).

Figure 6.

Specific binding of the SPOC domain to the C-terminal peptide from the SMRT/NCoR corepressor. (A) The C-terminal sequence is well conserved in SMRT homologs. The sequences from Drosophila SMRT homolog (SMRTER), human SMRT, and human NCoR are compared. The conserved residues in the homologs are highlighted in gray. A scrambled peptide, which has the same amino acid composition as the NCoR peptide, but in a different order, was used as a control peptide. (B) Binding assay with corepressor peptide affinity beads. 35S-labeled SPOC-195 was incubated with NHS affinity beads linked to the C-terminal NCoR or control peptides. The SPOC domain is able to bind to the NCoR peptide (left, lane 3), but not with the control peptide. The RRMs from SHARP showed no binding (right). (C) Competition assay with free NCoR and coactivator SRC-1 peptides. The 35S-labeled SPOC domain bound to the NCoR peptide affinity beads was challenged with free NcoR peptide (lanes 2-4, using 10, 50, and 100 μM) and free SRC-1 peptide (lanes 5-7, using 5, 10, and 100 μM). Quantitation of the competition assay is shown at bottom.

The specificity of the interaction was further confirmed by the addition of increasing concentrations of free peptide. The NCoR peptide efficiently caused dissociation of the SPOC domain (Fig. 6C, lanes 2-4). In contrast, a nonspecific peptide from the coactivator SRC-1 failed to compete (Fig. 6C, lanes 5-7). These results demonstrate that the SPOC domain specifically recognizes the conserved C-terminal LSD motif from SMRT/NCoR.

Mechanism of molecular recognition of SMRT/NCoR by the SPOC domain

The results described above raised the question as to whether the conserved basic patch is required for the specific recognition of the LSD motif from SMRT/NCoR. This was investigated through the introduction of alanine mutations in the SPOC domain (Fig. 5A). The resulting proteins were assessed for their ability to bind to the NCoR LSD peptide coupled to the resin. Remarkably, the single mutations K3516A and Y3602A, as well as the double mutant R3552A/R3554A, completely abolished binding to the NCoR peptide (Fig. 7A,B). In contrast, mutation of the nonconserved basic residues R3583A and K3596A, on the opposite side of the protein, had no effect on the interaction with the NCoR LSD peptide (Fig. 7B, bottom, right). Mutation of the conserved residue Trp 3509 resulted in a 30%-50% reduction of the binding efficiency with the NCoR peptide (Fig. 7B, top, middle). This residue is located a short distance from the basic patch and, unlike the other residues tested, is partially buried. It remains to be seen, therefore, whether this residue contributes to the interaction with SMRT/NCoR directly.

These findings clearly demonstrate that the conserved basic patch, including Tyr 3602, within the SPOC domain (Fig. 7A), is responsible for the specific interaction between SHARP and the conserved C terminus of SMRT/NCoR.

Discussion

The biological importance of the Spen proteins is well established. As discussed previously, they play a crucial role in the regulation of diverse developmental signaling pathways. In contrast, their function at the molecular level has been less clear. The conserved RRM domains of SHARP have been reported to mediate interaction with the coactivator RNA SRA (Shi et al. 2001). It remains unclear whether this RNA molecule is a unique partner for SHARP. The RRMs in MINT, the mouse homolog of SHARP, have been reported to interact specifically with G/T rich double-stranded DNA, suggesting that MINT might serve as a DNA-binding transcriptional repressor (Newberry et al. 1999). It is not obvious how these functions might be reconciled.

The region between the RRMs and SPOC domain shows little conservation between Spen proteins. The sequence has rather low complexity, consistent with structural predictions, which suggest that it might be unstructured. Within this region, several motifs have been shown to be important for interaction with transcription factors, including nuclear receptors, the notch factor RBP-Jκ, and the homeodomain protein Msx2.

The SPOC domain of the Spen proteins is the most conserved domain within the family and most likely, therefore, to shed light on the molecular role of these proteins. Its function has remained largely unexplored to date, but it is clear that deletion of the domain, or point mutations in the domain, result in severe perturbations in cell fate specification in Drosophila embryos (Wiellette et al. 1999; Chen and Rebay 2000). Analyses of the C terminus of SHARP have shown that a region a little larger than the SPOC domain is responsible for interaction with the histone deacetylase, HDAC1, and with the corepressor protein SMRT (Shi et al. 2001). It was not clear, however, whether these interactions represented the conserved evolutionary role of Spen proteins or whether they were specific to SHARP.

The structure of the SPOC domain reveals a novel architecture for an independent protein domain. (The β-barrel domain of Ku forms part of a larger structure.) It appears to be ideally suited to mediate interaction with other proteins through a number of deep grooves and clefts in the surface as well as two nonpolar loops. In addition, the N-terminal region seems to possess an intrinsic propensity to form a β-sheet with partner proteins. Most significantly, the structure reveals a highly basic patch on the surface, which is absolutely conserved throughout the Spen protein family. It is likely, therefore, that the function of this patch is indicative of the conserved role of the Spen proteins.

We have shown through a variety of interaction and mutagenesis experiments that this basic patch mediates the tight and specific interaction of the Spen proteins with the conserved acidic C-terminal LSD peptide from the SMRT/NCoR corepressors. Remarkably, point mutations within the basic patch totally abolish interaction with the LSD peptide. This suggests that although complementary charges play an important role in the interaction, the precise positioning of side chains of the key basic residues is absolutely required for stereospecific recognition of the SMRT/NCoR LSD motif. Whereas the precise details of the interaction remain to be determined, some indication of a possible mode of interaction is seen within the crystal lattice (Fig. 7C). The N-terminal region of one molecule (Pro 3495-Gln 3500) makes a crystal packing interaction with the β3 strand of an adjacent molecule (Arg 3548-Arg 3554). The interactions include backbone-backbone hydrogen bonds, as well as both electrostatic and hydrophobic interactions (Fig. 7C).

The conservation of the SPOC domain in Drosophila and Caenorhabditis elegans suggests that both these species should possess corepressor proteins with LSD motifs. It is clear that the rather divergent Drosophila corepressor SMRTER does have an almost identical LSD motif (Tsai et al. 1999). Our findings suggest that a similar protein must also be present in the worm.

It remains to be seen how other proteins such as HDAC1 may interact with SHARP. It is striking however that the LSD peptide itself serves as a potent transcriptional repressor, suggesting that recruitment of SHARP to a promoter is sufficient to mediate strong repression of basal transcription.

In conclusion, the combination of structural and functional experiments with the SPOC domain of SHARP clearly demonstrate that the conserved function of the SPOC domain is to mediate interaction with corepressors and, therefore, that Spen proteins play an essential role in regulating transcriptional repression.

Materials and methods

Preparation of recombinant C-terminal fragments of SHARP

DNA encoding each C-terminal fragment of human SHARP was amplified by PCR and cloned into the bacterial expression vector pET30a (Novagen) with an N-terminal hexa-histidine affinity tag (His-tag), in which the enterokinase cleavage site had been replaced by a tobacco etch virus (TEV) protease site. The His-tagged fragments were overexpressed in E. coli strain BL21(DE3)Rossetta-pLysS(Novagen). Cells were grown at 37°C in 2 L of 2TY medium containing kanamycin and chloramphenicol, both at 35 μg/mL, and induced at O.D.600nm = 0.4 with 0.4 mM isopropyl-β-D-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG). Four hours after the induction, the cells were harvested by centrifugation and stored at -20°C. The bacterial cells were lysed by sonication in buffer containing 20 mM sodium phosphate (pH 7.5), 300 mM NaCl, 5% glycerol, and 1 mM DTT (buffer A), and centrifuged to prepare cleared lysate. The supernatant was applied to a Ni-NTA agarose column (QIAGEN), and the His-tagged protein was eluted with buffer A containing 10 mM EDTA and 10 mM DTT. The His-tag was removed by 5-h digestion with His-tagged Tev protease at 4°C. After dialysis against buffer A, protein solution was reloaded onto a Ni-NTA affinity column to remove the cleaved tag and the Tev protease. The protein was further purified by a cation exchange (SP Sepharose) and anion exchange (Source Q) chromatography (Amersham-Pharmacia). The protein solution was finally concentrated to ∼20-25 mg/mL in 20 mM Na Phosphate (pH 7.5), 50 mM NaCl, 5% Glycerol, and 1 mM DTT, and was subjected to crystallization.

Cell-free synthesized proteins

Proteins were transcribed and translated in vitro in the presence of [35S]methionine using a T7 polymerase/S30 extract-coupled transcription/translation system according to the manufacturer's instruction (Novagen). The quality of translation and labeling were monitored using SDS-PAGE. The mutant proteins of the SPOC domain from SHARP were prepared using the Quick-change Multi mutagenesis kit (Stratagene). The mutations were confirmed by di-deoxy sequencing. The 35S-labeled mutants were synthesized in vitro.

GST pull-down assays

GST-tagged fragments of the C-terminal SHARP were expressed in E. coli strain BL21(DE3)Rossetta-pLysS(Novagen) and purified using glutathione-Sepharose 4B beads (Amersham-Pharmacia). Protein-protein interaction assays were performed by incubating gultathione-sepharose beads fused to GST fragments and [35S]methionine C-terminal SMRT in a binding buffer containing 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 100 mM NaCl, 0.5 mM EDTA, and 0.5% Triton X-100, at 4°C for 1 h. After extensive washing with the binding buffer, proteins remaining bound to the resin were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and visualized by an image plate scanner (Molecular Dynamics). Note that the dominant splice variant of SMRT was used (lacking residues 2353-2398).

Peptide interaction and competition assay

Synthetic peptides were coupled with NH-activated affinity resin according to the manufacturer's instruction (Amersham-Pharmacia). Peptide interaction assays were carried out by adding the 35S-labeled SPOC domain from SHARP to the peptide affinity resin in the binding buffer at 4°C for 1h. After extensive washing with the binding buffer protein, samples were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and visualized by an image plate scanner (Molecular Dynamics). Competition assays were performed under the same conditions by increasing free peptides. Gels were quantitated using an image plate scanner.

Preparation of Se-Met substituted protein

The SPOC-195 protein containing selenomethionine was expressed in B834(DE3). Cells were grown at 37°C in M9 medium supplemented with 40 mg/mL of each of 20 amino acids, including methionine. When the cells reached O.D.600nm = 0.4, they were harvested, washed with M9 salts, and resuspended in M9 medium lacking methionine. The cells were cultured for 30 min to deplete the intracellular methionine pool. After adding 0.4 mM IPTG and 40 mg/mL of selenomethionine, the cells were cultured for 4 h and harvested. The purification of the selenomethionine-labeled protein was carried out by the same procedure as that for the native protein, except for the buffer containing 10 mM of mercaptoethanol or 5 mM of DTT, in order to prevent oxidation of selenomethionine.

Crystallization and data collection

Crystallization was carried out using a vapor-diffusion method at 20°C. Crystals of SPOC-195 was grown in hanging drops of a mixture of 2.0 μL of protein solution and 1 μL of reservoir solution containing 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 30% PEG4000, and 5% glycerol. These crystals belong to the space group P212121 with cell dimensions a = 41.30 Å, b = 61.98 Å, c = 68.40 Å and with one molecule in an asymmetric unit. SeMet substituted protein was crystallized under the same conditions as the native, but containing 5 mM DTT.

The native and multiwavelength anomalous dispersion (MAD) data sets were collected at PX14.2, SRS, Daresbury, and at ID14-4 ESRF, Grenoble, respectively, at a temperature of 100 K. Crystals were flash-cooled under a nitrogen stream in cryoprotectant containing 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 100 mM NaCl, 25% PEG4000, and 20% glycerol. All data were indexed and integrated with the MOSFLM package (Leslie 1991). The lower resolution limit was determined by the backstop shadow. Subsequent crystallographic computations were performed using CCP4 suit of programs (Collaborative Computational Project, Number 4 1994).

Structure determination and refinement

Phase information was obtained using anomalous scattering from seleno-methionines with data collected at three wavelengths. Four selenium sites were located and phases were calculated at 1.8 Å using SOLVE (Terwilliger and Berendzen 1999). Solvent flattering was carried out with RESOLVE (Terwilliger and Berendzen 1999) assuming a 40.53% solvent content. Electron density map inspection and manual model building was carried out with O (Jones et al. 1991), and refinement with CNS (Brunger et al. 1998). An atomic model of SPOC-195 was refined against the statistically high quality data from 20 to 1.8 Å resolution with a crystallographic R factor of 21.4% and free R of 24.9% (Table 1). The final model contains residues 3495-3664, except for a disordered loop region (amino acids 3542-3544) and 82 water molecules. The coordinates have been deposited in the RCSB Protein Data Bank (PDB accession no. 1OW1).

Figure preparation

Figures 3A and B, 4, and 7C were prepared with Molscript (Kraulis 1991) and Rasted3D (Merrit and Bacon 1997). Figures 3C and 5B were made with GRASP (Nicholls et al. 1991). Figure 7A was generated with Swiss-PdbViewer (Guex and Peitsch 1997) and POV-Ray (http://www.povray.org).

Acknowledgments

We thank Ron Evans for providing clones of human SHARP and SMRT. We are grateful to Jan Löwe for help in MAD data collection at ESRF. We thank David Owen for help with peptide syntheses and James Love for helpful discussion. We acknowledge the European Synchrotron Radiation Facility Grenoble and the SRS Daresbury for provision of synchrotron radiation facilities, and we thank the staff on beamlines ID14-4 and PX14.2, respectively. M.A. was supported by TOYOBO and EMBO fellowships. This research was supported in part by HFSP and EU-RTN grants.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by payment of page charges. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

Corresponding author.

Article and publication are at http://www.genesdev.org/cgi/doi/10.1101/gad.266203.

References

- Bertrand N., Castro, D.S., and Guillemot, F. 2002. Proneural genes and the specification of neural cell types. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 3: 517-530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunger A.T., Adams, P.D., Clore, G.M., DeLano, W.L., Gros, P., Grosse-Kunstleve, R.W., Jiang, J.S., Kuszewski, J., Nilges, M., Pannu, N.S., et al. 1998. Crystallography & NMR system: A new software suite for macromolecular structure determination. Acta Crystallogr. D. Biol. Crystallogr. 54: 905-921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen F. and Rebay, I. 2000. split ends, a new component of the Drosophila EGF receptor pathway, regulates development of midline glial cells. Curr. Biol. 10: 943-946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J.D. and Evans, R.M. 1995. A transcriptional co-repressor that interacts with nuclear hormone receptors. Nature 377: 454-457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collaborative Computational Project, Number 4. 1994. The CCP4 suite: Programs for protein crystallography. Acta Crystallogr. D. Biol. Crystallogr. 50: 760-763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischle W., Dequiedt, F., Hendzel, M.J., Guenther, M.G., Lazar, M.A., Voelter, W., and Verdin, E. 2002. Enzymatic activity associated with class II HDACs is dependent on a multiprotein complex containing HDAC3 and SMRT/N-CoR. Mol. Cell 9: 45-57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glass C.K. and Rosenfeld, M.G. 2000. The coregulator exchange in transcriptional functions of nuclear receptors. Genes & Dev. 14: 121-141. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guex N. and Peitsch, M.C. 1997. SWISS-MODEL and the Swiss-PdbViewer: An environment for comparative protein modeling. Electrophoresis 18: 2714-2723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heinzel T., Lavinsky, R.M., Mullen, T.M., Soderstrom, M., Laherty, C.D., Torchia, J., Yang, W.M., Brard, G., Ngo, S.D., Davie, J.R., et al. 1997. A complex containing N-CoR, mSin3 and histone deacetylase mediates transcriptional repression. Nature 387: 43-48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hermanson O., Jepsen, K., and Rosenfeld, M.G. 2002. N-CoR controls differentiation of neural stem cells into astrocytes. Nature 419: 934-939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holm L. and Sander, C. 1993. Structural alignment of globins, phycocyanins and colicin A. FEBS Lett. 315: 301-306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horlein A.J., Naar, A.M., Heinzel, T., Torchia, J., Gloss, B., Kurokawa, R., Ryan, A., Kamei, Y., Soderstrom, M., Glass, C.K., et al. 1995. Ligand-independent repression by the thyroid hormone receptor mediated by a nuclear receptor corepressor. Nature 377: 397-404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jan Y.N. and Jan, L.Y. 1994. Neuronal cell fate specification in Drosophila. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 4: 8-13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jepsen K., Hermanson, O., Onami, T.M., Gleiberman, A.S., Lunyak, V., McEvilly, R.J., Kurokawa, R., Kumar, V., Liu, F., Seto, E., et al. 2000. Combinatorial roles of the nuclear receptor corepressor in transcription and development. Cell 102: 753-763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones T.A., Zou, J.Y., Cowan, S.W., and Kjeldgaard, M. 1991. Improved methods for building protein models in electron density maps and the location of errors in these models. Acta Crystallogr. A 47: 110-119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kao H.Y., Ordentlich, P., Koyano-Nakagawa, N., Tang, Z., Downes, M., Kintner, C.R., Evans, R.M., and Kadesch, T. 1998. A histone deacetylase corepressor complex regulates the Notch signal transduction pathway. Genes & Dev. 12: 2269-2277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolodziej P.A., Jan, L.Y., and Jan, Y.N. 1995. Mutations that affect the length, fasciculation, or ventral orientation of specific sensory axons in the Drosophila embryo. Neuron 15: 273-286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kraulis P.J. 1991. MOLSCRIPT: A program to produce both detailed and schematic plot of protein structure. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 24: 946-950. [Google Scholar]

- Kuang B., Wu, S.C., Shin, Y., Luo, L., and Kolodziej, P. 2000. split ends encodes large nuclear proteins that regulate neuronal cell fate and axon extension in the Drosophila embryo. Development 127: 1517-1529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurokawa R., Soderstrom, M., Horlein, A., Halachmi, S., Brown, M., Rosenfeld, M.G., and Glass, C.K. 1995. Polarity-specific activities of retinoic acid receptors determined by a co-repressor. Nature 377: 451-454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee S.K. and Pfaff, S.L. 2001. Transcriptional networks regulating neuronal identity in the developing spinal cord. Nat. Neurosci. 4: 1183-1191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leslie A.G.W. 1991. Pecent change to the MOCFLM package for processing film and image plate data. SERC Laboratory, Daresbury, Warrington, UK.

- Ma Z., Morris, S.W., Valentine, V., Li, M., Herbrick, J.A., Cui, X., Bouman, D., Li, Y., Mehta, P.K., Nizetic, D., et al. 2001. Fusion of two novel genes, RBM15 and MKL1, in the t(1;22)(p13;q13) of acute megakaryoblastic leukemia. Nat. Genet. 28: 220-221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mercher T., Coniat, M.B., Monni, R., Mauchauffe, M., Khac, F.N., Gressin, L., Mugneret, F., Leblanc, T., Dastugue, N., Berger, R., et al. 2001. Involvement of a human gene related to the Drosophila spen gene in the recurrent t(1;22) translocation of acute megakaryocytic leukemia. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 98: 5776-5779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merrit E.R. and Bacon, D.J. 1997. Raster3D-photorealistic molecular graphics. Methods Enzymol. 277: 505-524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagy L., Kao, H.Y., Chakravarti, D., Lin, R.J., Hassig, C.A., Ayer, D.E., Schreiber, S.L., and Evans, R.M. 1997. Nuclear receptor repression mediated by a complex containing SMRT, mSin3A, and histone deacetylase. Cell 89: 373-380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newberry E.P., Latifi, T., and Towler, D.A. 1999. The RRM domain of MINT, a novel Msx2 binding protein, recognizes and regulates the rat osteocalcin promoter. Biochemistry 38: 10678-10690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicholls A., Sharp, K.A., and Honig, B. 1991. Protein folding and association: insights from the interfacial and thermodynamic properties of hydrocarbons. Proteins 11: 281-296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ordentlich P., Downes, M., Xie, W., Genin, A., Spinner, N.B., and Evans, R.M. 1999. Unique forms of human and mouse nuclear receptor corepressor SMRT. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 96: 2639-2644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oswald F., Kostezka, U., Astrahantseff, K., Bourteele, S., Dillinger, K., Zechner, U., Ludwig, L., Wilda, M., Hameister, H., Knochel, W., et al. 2002. SHARP is a novel component of the Notch/RBP-Jκ signalling pathway. EMBO J. 21: 5417-5426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rebay I., Chen, F., Hsiao, F., Kolodziej, P.A., Kuang, B.H., Laverty, T., Suh, C., Voas, M., Williams, A., and Rubin, G.M. 2000. A genetic screen for novel components of the Ras/Mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling pathway that interact with the yan gene of Drosophila identifies split ends, a new RNA recognition motif-containing protein. Genetics 154: 695-712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuurmans C. and Guillemot, F. 2002. Molecular mechanisms underlying cell fate specification in the developing telencephalon. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 12: 26-34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi Y., Downes, M., Xie, W., Kao, H.Y., Ordentlich, P., Tsai, C.C., Hon, M., and Evans, R.M. 2001. Sharp, an inducible cofactor that integrates nuclear receptor repression and activation. Genes & Dev. 15: 1140-1151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terwilliger T.C. and Berendzen, J. 1999. Automated MAD and MIR structure solution. Acta Crystallogr. D. Biol. Crystal-logr. 55: 849-861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson J.D., Higgins, D.J., and Gibson, T.J. 1994. CLUST AL_W: Improving the sensitivity of progressive multiple sequence alignment through sequence weighting, position-specific gap penalties and weight matrix choice. Nucleic Acids Res. 22: 4673-4680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsai C.C., Kao, H.Y., Yao, T.P., McKeown, M., and Evans, R.M. 1999. SMRTER, a Drosophila nuclear receptor coregulator, reveals that EcR-mediated repression is critical for development. Mol. Cell 4: 175-186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiellette E.L., Harding, K.W., Mace, K.A., Ronshaugen, M.R., Wang, F.Y., and McGinnis, W. 1999. spen encodes an RNP motif protein that interacts with Hox pathways to repress the development of head-like sclerites in the Drosophila trunk. Development 126: 5373-5385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoon H.G., Chan, D.W., Huang, Z.Q., Li, J., Fondell, J.D., Qin, J., and Wong, J. 2003. Purification and functional characterization of the human N-CoR complex: The roles of HDAC3, TBL1 and TBLR1. EMBO J. 22: 1336-1346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J., Kalkum, M., Chait, B.T., and Roeder, R.G. 2002. The N-CoR-HDAC3 nuclear receptor corepressor complex inhibits the JNK pathway through the integral subunit GPS2. Mol. Cell 9: 611-623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]