Abstract

Objective To assess the effect of community prescribing of an antibiotic for acute respiratory infection on the prevalence of antibiotic resistant bacteria in an individual child.

Study design Observational cohort study with follow-up at two and 12 weeks.

Setting General practices in Oxfordshire.

Participants 119 children with acute respiratory tract infection, of whom 71 received a β lactam antibiotic.

Main outcome measures Antibiotic resistance was assessed by the geometric mean minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) for ampicillin and presence of the ICEHin1056 resistance element in up to four isolates of Haemophilus species recovered from throat swabs at recruitment, two weeks, and 12 weeks.

Results Prescribing amoxicillin to a child in general practice more than triples the mean minimum inhibitory concentration for ampicillin (9.2 µg/ml v 2.7 µg/ml, P=0.005) and doubles the risk of isolation of Haemophilus isolates possessing homologues of ICEHin1056 (67% v 36%; relative risk 1.9, 95% confidence interval 1.2 to 2.9) two weeks later. Although this increase is transient (by 12 weeks ampicillin resistance had fallen close to baseline), it is in the context of recovery of the element from 35% of children with Haemophilus isolates at recruitment and from 83% (76% to 89%) at some point in the study.

Conclusion The short term effect of amoxicillin prescribed in primary care is transitory in the individual child but sufficient to sustain a high level of antibiotic resistance in the population.

Introduction

The correlation between community use of penicillin and penicillin resistance across 19 European countries has recently been reported as 0.84.1 The regression line rises steeply—for example, in France the rate of penicillin prescribing is 2.5 times that in the United Kingdom but the proportion of non-susceptible Streptoccus pneumoniae is 10 times higher (40% v 4%). This steep dose-effect relation contrasts starkly with the weak relation between antibiotic prescribing and resistance that we and others have previously reported from UK general practice.2 3

Although a strong correlation between antibiotic prescribing and resistance might seem inevitable from a Darwinian perspective, the relation is complex.4 Actual resistance levels will depend on the pattern of antibiotic use, the specific interaction between bacterium and drug, the potential for transmission, and the stage the country is at in the evolution of resistance. For example, Sweden and Denmark have higher rates of penicillin prescribing than the UK but lower resistance, while Finland has lower prescribing but higher resistance.1 Similarly, community studies from Iceland have shown that the association between a reduction in prescribing and resistance is not straightforward.5 6 To develop an effective strategy to manage antibiotic resistance in the community we need to understand what is happening at the level of the individual patient, not just to inform care of patients but also to provide firm estimates for the population models that should inform policy on antibiotic prescribing.

The highest rates of antibiotic prescribing in primary care are to children with respiratory illness but surprisingly there have been few prospective controlled studies of the impact of such prescribing on resistance in a community setting. In the 1980s Brook reported isolation of β lactam producing bacteria in 46% of children one week after antibiotic treatment of otitis media or pharyngitis and 27% after three months compared with a constant 11% in controls.7 A paper from Malawi in 2000 reported recovery of co-trimoxazole resistant pneumococci in 52% of children one week after malaria treatment with co-trimoxazole compared with 34% in controls but with no difference after four weeks.8 An Australian study in 2002 reported a twofold increase in the odds of recovery of resistant pneumococci in children who had used β lactam antibiotics in the two months before swab collection.9 We report a prospective study in children from UK general practice with new methods for identifying a highly mobile integrative and conjugative element (ICE) that encodes β lactamase and circulates among nasopharyngeal Haemophilus species.10 11 12

Methods

Participants

General practitioners initially recruited 150 children aged 6 months to 12 years presenting with either otitis media or a suspected respiratory infection. Thirty one were excluded from this analysis because they were prescribed a macrolide (n=7), co-amoxiclav (n=1), or received a further course of antibiotics at another consultation during the 12 week follow-up period (n=23). We therefore included 119 children, of whom 71 were prescribed a β lactam antibiotic (amoxicillin 70, cephradine 1) at presentation and 48 received no antibiotic.

Data collection and follow-up

A research nurse collected information on sociodemographic details, type of infection, child's past antibiotic use, and treatment for current illness as well as obtaining ethical consent from the parent. Information on antibiotic prescribing was confirmed from the medical records. Children were followed up on two occasions, at two weeks and 12 weeks after recruitment.

Microbiology

A trained research nurse took throat swabs. Each cotton tipped wooden swab was transported in enriched tryptic soy broth. The samples were vortexed and the broth stored at −80°C for batch processing. At the time of processing, 50 µl samples were inoculated onto two Haemophilus selective media: Columbia agar (enriched with haemin and nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide) plus bacitracin, and the same agar with the addition of 2 µg/ml ampicillin. Plates were incubated at 37°C plus 5% CO2 for 48 hours. Up to four morphologically different colonies were picked from the bacitracin plate and two morphologically different colonies from the ampicillin plate. The colonies were purified by subculturing on to chocolate agar. Assessment of ampicillin minimum inhibitory concentration level (Etest, AB Biodisk, Solna, Sweden) was performed in accordance with US National Committee of Clinical and Laboratory Standards guidelines. The presence of the integrative and conjugative element homologous to ICEHin1056 was performed following a method previously described13 with a multiplex assay targeting regions of the topoisomerase gene and orf 51 (as annotated in the complete sequence of ICEHin1056; accession number AJ627386, table 1).

Table 1.

Polymerase chain reaction primers for identification of integrative and conjugative resistance elements (ICE)

| Primer and direction | Oligonucleotide sequence (5′ to 3′) | Length of fragment (base pairs) |

|---|---|---|

| Topoisomerase | ||

| Forward | GAG ACT CAC AAA GCG ACA ACC | 435 |

| Reverse | GGC TTG AGG TGC GTC ATC ATC TTC | |

| ORF 51 | ||

| Forward | CGG TTC CAG TGT TAT ATT CAC G | 515 |

| Reverse | GAA TGT GAT CGG TGA GAA GC | |

We looked for the integrative and conjugative element in the Haemophilus species isolated from the bacitracin agar plate (which selects for Haemophilus species and against other bacterial genera). We estimated the minimum inhibitory concentration for ampicillin from isolates selected from the ampicillin agar plate. The extent of double counting of isolates based on morphological appearance was assessed by comparing the DNA sequences of regions of the mdh and frdB housekeeping genes in 188 isolates (four isolates from 47 plates). Identical mdh and frdB alleles would suggest that strains of Haemophilus species were indistinguishable. Results showed no double counting of indistinguishable strains in 21 plates, one isolate double counted in 19 plates, and two isolates double counted in seven plates. We have therefore presented the integrative and conjugative element data using the child rather than the isolate as a denominator.

Analysis

Analysis of data was performed with SPSS for Windows (version 12.0). We used the χ2 test to compare categorical data between groups at each visit. As the minimum inhibitory concentration for ampicillin is highly skewed we applied a log transformation to this measurement and used geometric means to summarise this measure. We used t tests to compare the means between groups at each visit and paired t tests to compare the means within groups. Where data are reported in relation to individual children rather than individual isolates, the denominator is limited to children in whom Haemophilus species were isolated (because antibiotic resistance is a characteristic of the colonising bacterium, not of the child). As we recovered Haemophilus species from nearly all children, however, the results would be similar if we included all children in the denominator.

Results

Completeness of follow-up and recovery of target bacterium

Loss to follow-up was small: nine children (8%) at two weeks, 10 children (9%) at 12 weeks. Recovery of Haemophilus species was high and increased with each visit: 101/119 (85%) children at baseline, 101/110 (92%) at two weeks, and 106/109 (97%) at 12 weeks, with little difference between the antibiotic and no antibiotic groups.

Initial differences between children

Table 2 provides data on children according to whether they were prescribed an antibiotic. Mean age (both 5.4 years), mean number of children in household (1.16 v 1.13), and previous exposure to antibiotics (87% v 85%) were similar. Day care or school attendance was more common in the children who received an antibiotic (66/69 (95%) v 40/47 (85%), P=0.05). The geometric mean of the minimum inhibitory concentration for ampicillin of the Haemophilus species isolates was 2.4 µg/ml in the antibiotic group and 4.1 µg/ml in the no antibiotic group (P=0.24). The proportion of children with an isolate carrying an integrative and conjugative element was 32% and 38%, respectively (P=0.52). Carriage of the element was common even in children who had never received an antibiotic (8/15, 53%).

Table 2.

Characteristics of children included in the analysis. Figures are numbers (percentages) of children unless stated otherwise

| All children (n=119) | Received β lactam antibiotic (n=71) | Did not receive β lactam antibiotic (n=48) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) age of child (years) | 5.4 (3.1) | 5.4 (3.3) | 5.4 (2.8) |

| Mean (SD) age of mother (years) | 36.3 (7.7) | 36.7 (9.2) | 35.6 (4.7) |

| No of children in household | 1.14 (1) | 1.16 (1) | 1.13 (1) |

| Female | 60/119 (50) | 34/71 (48) | 26/48 (54) |

| Previous antibiotics in life* | 103/119 (87) | 62/71 (87) | 41/48 (85) |

| Previous antibiotic in past 3 months* | 18/114 (16) | 9/68 (13) | 9/46 (20) |

| Antibiotic use in household in past 3 months* | 48/108 (44) | 29/64 (45) | 19/44 (43) |

| Single parent family* | 16/118 (14) | 10/71 (14) | 6/47 (13) |

| Attends day care or school* | 106/116 (91) | 66/69 (96) | 40/47 (85) |

*Data from questionnaire completed by parent; denominator is number of parents responding to question.

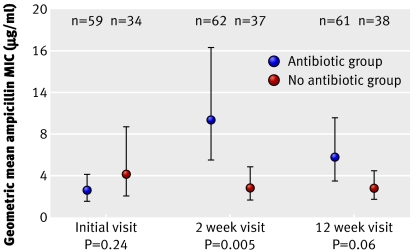

Effect of antibiotics on ampicillin minimum inhibitory concentration

The figure shows that in children who did not receive an antibiotic, the geometric mean minimum inhibitory concentration for ampicillin was the same (2.7 µg/ml) at both follow-up points, with no significant change from the initial level of 4.1 µg/ml. In contrast, in children who received an antibiotic, the minimum inhibitory concentration increased about fourfold to 9.2 µg/ml at the two week follow-up (ratio to no antibiotic group 3.5, P=0.005). At the 12 week follow-up, it fell back to 5.7 µg/ml (ratio to no antibiotic group 2.1, P=0.06). We were able to calculate a measure of change between the initial visit and 12 week follow-up in 86 children (54 in antibiotic group, 32 in no antibiotic group). The ratio of geometric mean minimum inhibitory concentration at 12 weeks compared with initial visit was 2.33 in children who received an antibiotic and 0.71 in those who did not (P=0.05).

Geometric mean minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) for ampicillin of isolates from children according to whether or not they received antibiotics (error bars show 95% confidence intervals; P values based on t test)

Effect of antibiotics on carriage of an integrative and conjugative element

Table 3 shows the proportion of children from whom we recovered an integrative and conjugative element at each visit. As with the minimum inhibitory concentration for ampicillin, there was little change in recovery from children who did not receive an antibiotic at the two week (36%) and 12 week (37%) follow-up visits. In the antibiotic group, however, recovery doubled to 67% at two weeks (P=0.002) before falling back to 36% (close to the baseline level of 32%) at 12 weeks. Table 3 also shows that the approximate doubling of risk of carriage at two weeks and the fall close to baseline by 12 weeks were consistent whether or not a resistant element had been recovered from the child at the initial visit. An integrative and conjugative element was recovered from most children from whom Haemophilus species were isolated (83%, 95% confidence interval 76% to 89%) at some point in the study, irrespective of whether they received an antibiotic.

Table 3.

Isolation of integrative and conjugative resistance element (ICE) at follow-up according to antibiotic prescribing and whether element was isolated at initial visit. Figures are numbers (percentages) of children unless stated otherwise

| Children prescribed antibiotic (n=71) | Children not prescribed antibiotic (n=48) | Risk (risk ratio) of isolation of resistance element at follow-up if antibiotic prescribed (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| ICEHin1056 isolated at initial visit | 20/62 (32) | 15/39 (38) | — |

| ICEHin1056 isolated at 2 week visit: | |||

| Total | 42/63 (67) | 14/39 (36) | 1.9 (1.3 to 2.7) |

| Isolated at initial visit* | 15/20 (75) | 6/15 (40) | 1.9 |

| Not isolated at initial visit* | 25/42 (60) | 7/24 (29) | 2.0 |

| ICEHin1056 isolated at 12 week visit: | |||

| Total | 24/66 (36) | 15/40 (37) | 1.0 (0.5 to 1.7) |

| Isolated at initial visit* | 10/20 (50) | 7/15 (47) | 1.1 |

| Not isolated at initial visit* | 12/42 (29) | 8/24 (33) | 0.9 |

*Do not sum to total for all children because Haemophilus species were not isolated from every child at every visit (see text).

Discussion

The short term effect of amoxicillin prescribed in primary care is transitory in the individual child but sufficient to sustain a high level of antibiotic resistance in the population. The inclusion of commensal as well as pathogenic Haemophilus species and the focus on mobile resistance elements allowed us to avoid the bias inherent in previous studies (that is, the differential recovery of bacteria in intervention and treatment groups). It also allowed us to characterise the bacterial flora from more than a single isolate even when we sampled by throat swab. Although the design was observational, the similarity of baseline characteristics and levels of initial resistance, plus the lack of any suggestion that the integrative and conjugative element is associated with disease virulence or a pathogenic factor,11 12 makes serious confounding unlikely.

The integrative and conjugative element can be isolated from both pathogenic H influenzae and commensal H parainfluenzae and like a plasmid moves freely between them by horizontal transfer.12 13 14 It is this global gene pool of transferable antibiotic resistance elements that maintains antibiotic resistance in the community. We recognise that other potential respiratory tract pathogens accrue resistance (including penicillin resistance in pneumococci and methicillin resistance in staphylococci) by mutation of chromosomal genes rather than conjugative mechanisms and therefore we cannot necessarily generalise our results to those species. Our results, however, are consistent with the report by Nasrin et al of a doubling of odds of isolation of penicillin resistant pneumococci from children who had received a β lactam antibiotic within two months but not six months.9

Prescribing antibiotics to children remains common practice. A paper published in 1999 reported that 55% of children aged 0-5 years in the UK (the group of patients who receive most antibiotics in the community) receive an average of 2.2 prescriptions for a β lactam antibiotic from their general practitioner each year.15 Although a reduction in prescribing (and the strategy of recommending a 24-48 hour delay before filling antibiotic prescriptions) has probably resulted in about a 40% fall in consumption since then,16 unpublished data reported to the paediatric subgroup of the standing advisory committee on antibiotic resistance suggest that community antibiotic prescribing is again rising.

Using our results to estimate the effect of this prescribing on resistance is not straightforward. If our ability to recover an integrative and conjugative element mirrors the change in transmission potential, the marginal effect of community prescribing on the proportion of children in the UK who are able to transmit an integrative and conjugative element at any one time is perhaps 2-3%. However, this does not imply a marginal 2-3% impact on resistance because this is not a static system. For example, applying a transmission dynamics model to data from Finland, Austin et al showed that a paediatric prescribing rate of 14 days of antibiotics each year, and an estimated duration of carriage of a β lactamase producing strain of Moraxella catarrhalis of just over one month, was consistent with an increase in community prevalence of these strains by about 10% a year to an equilibrium level of about 50%.17 These parameter estimates are not dissimilar in magnitude to the prescribing rates cited above and the duration of increased recovery of the integrative and conjugative element we observed.

Clinical implications

In the few cases where it is appropriate to repeat the prescription of an antibiotic within under three months, it may be sensible to choose one (for example, co-amoxiclav) that has activity against β lactamase producing strains, rather than give a further course of amoxicillin. From a population perspective, the issue of concern is the high (about 35%) equilibrium level of recovery of resistant Haemophilus species to which the children receiving antibiotics returned after 12 weeks and the endemic carriage of the integrative and conjugative element by nasopharyngeal Haemophilus species. This may indicate that bacteria can adapt to carry the resistance element with minimal metabolic cost and therefore without much biological disadvantage in the absence of antibiotic selection. In this situation, the model proposed by Austin et al further predicts that any reduction in community resistance is likely to need a substantial and sustained reduction in community prescribing.17 One option that deserves further investigation, and is supported by Nasrin's data,9 is to reduce the duration of each course of antibiotics prescribed in the community. A more radical option is to advise stopping prescribing antibiotics to any child with respiratory infection in the community except in well defined and exceptional circumstances. Although such a strategy may be easier to implement than a discretionary policy based on the difficult, and perhaps impossible, clinical discrimination between viral and bacterial infection, it does run the risk of some children with bacterial disease being treated later in the course of their illness.

What is already known on this topic

UK general practitioners are strongly encouraged to reduce antibiotic prescribing to minimise the risk of antibiotic resistance

Epidemiological studies of the likely effect of reducing antibiotic prescribing outside hospital on antibiotic resistance have reported inconsistent results

What this study adds

Prescribing amoxicillin to a child in general practice doubles the risk of recovering a β lactamase encoding resistance element from that child's throat two weeks later

This risk falls back to the level seen before treatment within 12 weeks, but a β lactamase inhibitor combination antibiotic should probably be prescribed during this period

The ICEHin1056 resistance element is endemic in UK children, but reversal of this will require further substantial and sustained changes in antibiotic prescribing in the community

Contributors: AC carried out this research as part of her DPhil thesis. RP supervised the statistical analysis. ABB supervised the laboratory work and microbiological analysis. AE undertook some of the gene sequencing as part of his DPhil thesis. AH and RM-W helped to design the project and draft the paper. SS oversaw the data management and assisted in the analysis. DC designed and oversaw the microbiology and supervised AC. DM obtained the funding, supervised AC, and drafted the paper. All authors commented on and contributed to various drafts of the paper and read and approved the final draft. AC and DM are guarantors.

Funding: Medical Research Council. Oxford University department of primary health care also receives programme funding for this area of research as part of the NIHR National School of Primary Care Research.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethical approval: Central Oxford NHS research ethics committee.

Provenance and peer review: Non-commissioned, externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Goosens H, Ferech M, Stichele RV, Elseviers M. Outpatient antibiotic uses in Europe and association with resistance: a cross-national database study. Lancet 2005;365:579-87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Priest P, Yudkin P, McNulty C, Mant D, Wise R. Antibacterial prescribing and antibacterial resistance in English general practice: cross sectional study BMJ 2001;323:1037-41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Donnan PT, Wei L, Steinke DT, Phillips G, Clarke R, Noone A, et al. Presence of bacteriuria caused by trimethoprim resistant bacteria in patients prescribed antibiotics: multilevel model with practice and individual patient data. BMJ 2004;328:1297-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Turnidge J, Christiansen K. Antibiotic use and resistance—proving the obvious. Lancet 2005;365:548-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Arason VA, Kristinsson KG, Sigurdsson JA, Stefansdottir G, Molstad S, Gudmundsson S. Do antimicrobials increase the carriage rate of penicillin resistant pneumococci in children? Cross sectional prevalence study. BMJ 1996;313:7054-91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Arason VA, Gunnlaugsson A, Sigurdsson JA, Erlendsdottir H, Gudmundsson S, Kristinsson KG. Clonal spread of resistant pneumococci despite diminished antimicrobial use. Microb Drug Resist 2002;8:3-92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brook I. Emergence and persistence of beta-lactamase producing bacteria in the oropharynx following penicillin treatment. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 1988;114:667-70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Feikin DR, Dowell SF, Nwanyanwu OC, Klugman KP, Kazembe PN, Barat LM, et al. Increased carriage of trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole-resistant Streptococcus pneumoniae in Malawian children after treatment for malaria with sulfadoxine/pyrimethamine. J Infect Dis 2000;181:4-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nasrin D, Collignon P, Roberts L, Wilson E, Pilotto S, Douglas M. Effect of beta lactam antibiotic uses in children on resistance to penicillin: prospective cohort study. BMJ 2002;324:1-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mohd-Zain Z, Turner SL, Cerdeno-Tarraga AM, Lilley AK, Inzana TJ, Duncan AJ, et al. Transferable antibiotic resistance elements in Haemophilus influenzae share a common evolutionary origin with a diverse family of syntenic genomic islands. J Bacteriol 2004;186:8114-22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dimopoulou I, Russell J, Mohd-Zain Z, Herbert R, Crook DW. Site-specific recombination with the chromosomal tRNA(Leu) gene by the large conjugative Haemophilus resistance plasmid. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2002;46:1602-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Leaves N, Dimopoulou I, Hayes I, Kerridge S, Falla T, Secka O, et al. Epidemiological studies of large resistance plasmids in Haemophilus. J Antimicrob Chemother 2000;45:599-604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dimopolou I, Kartali S, Harding R, Peto T, Crook D. Diversity of antibiotic resistnace integrative and congugative elements among haemophili. J Med Microbiol 2007;56:838-46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Scheifele DW, Fussel SJ, Roberts MC. Characterization of ampicillin-resistant Haemophilus parainfluenzae. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 1982;21:734-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Majeed A, Moser K. Age- and sex-specific antibiotic prescribing patterns in general practice in England and Wales in 1996. Br J Gen Pract 1999;49:735-6. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sharland M, Kendall H, Yeates D, Randall A, Hughes G, Glasziou P, et al. Antibiotic prescribing in general practice and hospital admissions for peritonsillar abscess, mastoiditis and rheumatic fever in children: time trend analysis. BMJ 2005;331:328-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Austin D, Kristinsson K, Anderson R. The relationship between the volume of antimicrobial consumption in human communities and the frequency of resistance. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1999;96:1152-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]