Abstract

Objectives. We sought to identify the functional, cognitive, and social factors associated with self-neglect among the elderly to aid the development of etiologic models to guide future research.

Methods. A cross-sectional chart review was conducted at Baylor College of Medicine Geriatrics Clinic in Houston, Tex. Patients were assessed using standardized comprehensive geriatric assessment tools.

Results. Data analysis was performed using the charts of 538 patients; the average patient age was 75.6 years, and 70% were women. Further analysis in 460 persons aged 65 years and older showed that 50% had abnormal Mini Mental State Examination scores, 15% had abnormal Geriatric Depression Scale scores, 76.3% had abnormal physical performance test scores, and 95% had moderate-to-poor social support per the Duke Social Support Index. Patients had a range of illnesses; 46.4% were taking no medications.

Conclusions. A model of self-neglect was developed wherein executive dyscontrol leads to functional impairment in the setting of inadequate medical and social support. Future studies should aim to provide empirical evidence that validates this model as a framework for self-neglect. If validated, this model will impart a better understanding of the pathways to self-neglect and provide clinicians and public service workers with more effective prevention and intervention strategies.

Self-neglect is the inability to provide for oneself the goods or services to meet basic needs. In almost every US jurisdiction, it is the most common problem faced by Adult Protective Service agencies.1–3 Two national studies reported the prevalence of self-neglect to be 50.3% and 39.1%4,5 among Adult Protective Service clients. These numbers may represent a low estimate because 15 states do not mandate the reporting of this form of mistreatment. In a client-matched study of the Established Populations for Epidemiological Studies in the Elderly database and the records of the Connecticut Ombudsman’s Office, 72.7% of the Adult Protective Service clients were reported as having issues of self-neglect.2 In a population-based study of Texas adult protective services division of the state protective services program, 62.5% of the clients were referred for self-neglect, with 90% of the self-neglect cases occurring in persons aged 65 years and older.1 Not only is self-neglect common, but it also has been shown to be an independent risk factor for death.6

Individuals who neglect themselves are typically older persons with multiple deficits in social, functional, and physical domains and who in extreme instances live in squalor. First described in the 1960s in the United States7 and Great Britain,8 self-neglect was called the “Social Breakdown Syndrome” or “Senile Breakdown.” Others have used the term “Diogenes Syndrome”9 for those who hoard as well as live in squalor, although the term also describes younger patients with mental illness, patients with personality disorders, and persons without identifiable diagnoses. In the late 1970s, the term “self-neglect” came into use in the medical and social service literature. A number of studies have been published on self-neglect; those studies with descriptive information on persons who self-neglect included 30 to 233 persons for a total of 548 persons.8–14

Despite these studies, there is still no clear case definition for self-neglect. We aimed to describe the characteristics of 538 instances of self-neglect reported to an urban protective service agency, which were subsequently referred to an interdisciplinary geriatrics medicine team. We report the demographics, medical diagnoses, medication use, and the results of geriatric assessment measures in this large sample to clarify the case definition for self-neglect and to present a model for future studies.

METHODS

The patients reported in this study were clients of adult protective services workers, who are charged with investigating and intervening in cases of abuse in adults. They referred cases of self-neglect to the geriatric medicine team, comprised of geriatricians, geriatric nurse practitioners, a gerontologic social worker, nurses, and physical and occupational therapists. The local adult protective services for Region VI serves the Houston metropolitan area and surrounding counties. Statewide statistics show that from 1999 to 2004 (fiscal year data) 365 199 cases of elder mistreatment were reported. Approximately 61% of these reports involved allegations of self-neglect. During that period, Region VI received 60 344 allegations of self-neglect, of which 572 were referred to the geriatric medicine team. This region included 13 counties where there were 2 864 493 persons aged younger than 65 years and 335 480 persons aged 65 years and older. Of the self-neglect cases, 538 had adequate data for analysis; 460 (86%) of those were persons aged 65 years and older.

Referral Procedure

In Region VI, adult protective services workers have the option of referring cases to the geriatric medicine team according to their own discretion. Eligible patients are victims of elder mistreatment and are thought by adult protective services workers to have a medical or psychiatric condition. In addition, the patients must display 1 or more of the following: (1) questionable decisionmaking capacity; (2) reluctance to leave their homes to visit a doctor’s office, clinic, or hospital; (3) lack of medical care for a prolonged period of time; (4) inability to see his or her own physician in a timely manner; (5) possible underdiagnosis, overmedication, or inadequate care; or (6) the need for a specialized interdisciplinary geriatric approach. The guidelines used were designed to be inclusive and to encourage caseworkers to send clients if they thought they could benefit from the services of the geriatric medicine team. In general, adult protective services workers refer to the geriatric medicine team if a client could benefit from the Harris County Hospital District services or requires a house call. The caseworkers state that they send their most difficult clients to the geriatric medicine team. The patients referred to the geriatric medicine team were similar to persons described in the literature.1–12 Caseworkers complete a 1-page form to refer each client. This form is faxed to the geriatric medicine team and a case manager calls the adult protective services worker to determine if the client should be seen in the outpatient setting or on a house call.

Measurements

Demographic data inclusive of age, gender, ethnicity, and income were collected as part of the comprehensive geriatric assessment. In addition, a battery of geriatric assessment measures was administered to each patient—the Mini Mental State Examination (cognition),15 the Geriatric Depression Scale (depression),16 the physical performance test (activities of daily living),17,18 the clock drawing test (executive function),19 the Functional Activities Questionnaire (activities of daily living),20,21 the self-health question from the First National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey,22 the Duke Social Support Index (social support),23,24 and the Cut-Annoyed-Guilt-Eye Opener (CAGE) questionnaire (alcohol use).25

The assessment tools were selected because they were standardized tests and could be briefly administered in the outpatient clinic or during a house call. Additionally, these tools assess distinct domains that aid in the diagnosis, treatment, follow-up, and coordination of care by an interdisciplinary team and are commonly used in geriatric medicine. A number of the older persons referred by adult protective services could not complete the entire battery because of unwillingness or inability; for these people data were obtained whenever possible.

The data were recorded in charts by clinicians (nurse practitioners, social workers, or geriatricians) and later loaded into a Microsoft Access 2000 (Microsoft Corp, Redmond, Wash) database by a data entry clerk and medical secretaries. Because the data were collected by multiple clinicians over several years, in 2005 every chart was reviewed again by coauthors (S. P.-P. and J. B.) for accuracy of data entry. In 34 (6%) instances, the chart could not be located for review and these patients were eliminated from the analysis. The data were subsequently analyzed with SPSS version 12 (SPSS Inc, Chicago, Ill).

RESULTS

Demographics

There were 538 patients diagnosed with self-neglect whose records had adequate data for analysis. The average age of the patients was 75.6 ± 11.1 years, and 70% were women. African Americans made up 49.1% of the total sample, and Whites, 41.9%; 7.4% of the sample were Hispanic, and 1.4% were from other racial/ethnic groups. Income data were available for 268 patients, and the average was $817.20 ± $707.6 per month.

Further analysis was performed on an elderly subset of the total sample. Of the 538, 460, or 86%, were aged 65 years or older. In this older age group, the majority of patients referred were women (71.7%), and African Americans were the most common ethnic group represented (49.3%). The rest of the subsample was 40.9% White, 6.3% Hispanic, and 1.3% Asian. Nearly 50% of the patients referred to the generic medicine team were aged between 75 and 84 years.

A more detailed analysis was performed in the older group (individuals aged 65 years and older) because they made up the majority of patients and were of interest to the geriatric team. Furthermore, the clinical team administered a geriatric assessment to these individuals, and it was deemed most appropriate to report on geriatric assessment in geriatric patients. Of the frail elderly persons who neglect themselves, 15 (3.3%) refused to complete any of the proposed measures and 12 (2.6%) were too impaired to complete any of the measures. Only 36 (7.8%) patients had missing charts and thus no data were available for analysis.

Medical Disorders

Information about medical diagnoses was available for 372 (81%) patients. Table 1 ▶ provides a list of the 10 most frequently diagnosed medical disorders. Some of these diagnoses were reported by the patients, and some were noted by the clinician who saw the patient. In many instances the patients did not know their diagnoses and could not provide any history. The breakdown of medical diagnoses is described in Table 1 ▶ by broad category and specific diagnoses. The most common category of disease was cardiovascular disorders (84%), with hypertension (51.6%) the most frequent overall diagnosis listed. Mental disorders (53%) were the second most commonly listed diagnosis, with dementia (15.9% of the total sample), depression (14.3% of the total sample), and delirium (7.3% of the total sample) the most common. Endocrine disorders (30.4%) were the third most commonly reported diagnosis, with diabetes mellitus occurring in 25.2% of all patients. Many of the diagnoses noted in the self-neglecters were the same as those commonly diagnosed and treated by geriatric medicine teams.

1.

Most Common Medical Diagnoses and Medications Among Elderly Self-Neglect Patients: Houston, Tex, 1999–2004

| No. (%) | |

| Diagnoses | |

| Hypertension | 192 (51.6) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 94 (25.2) |

| Arthritis | 75 (20.1) |

| Dementia | 73 (29.7) |

| Cerebrovascular accident | 66 (17.7) |

| Depression | 53 (14.3) |

| Coronary artery disease | 35 (9.4) |

| Urinary incontinence | 28 (7.5) |

| Delirium | 27 (7.3) |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 26 (7) |

| Medication type | |

| Antihypertensive | 84 (24.3) |

| Diabetic agents | 51 (14.8) |

| Aspirin | 45 (13.0) |

| Cardiovascular agents (not antihypertensives) | 44 (12.8) |

| Antidepressants | 42 (12.2) |

| Diuretics | 29 (8.4) |

| Alzheimer disease management drugs | 27 (7.8) |

| Over-the-counter analgesics | 27 (7.8) |

| Nonsteroidal anti- inflammatory drugs | 24 (6.9) |

| Psychotropics | 21 (6.1) |

| Respiratory agents | 21 (6.1) |

| Thyroid hormones | 20 (5.8) |

| None | 160 (46.4) |

Note. The percentages do not sum to 100% because of subject comorbidities. Patients with missing data = 88.

Number and Types of Medications

Data about medications were available on 345 (75%) patients. Whereas 185 were taking medications excluding vitamin supplements, 160 (46.4%) were on no medications including vitamin supplements. The median was 1 medication, with a mean of 2.55; the 75th percentile was 5 medications. The medications most commonly taken are described in Table 1 ▶. Antihypertensive, diabetic, and cardiovascular agents represented 24%, 15%, and 13% of the medications prescribed, respectively.

Results of Geriatric Assessment Measures

A battery of assessment measures was administered to patients as a part of the geriatric medicine team’s evaluation. Not every patient underwent each measure, because the number of tests in the battery evolved over the years as the clinicians determined that more clinical information was needed. Two hundred fifty-six individuals provided data for 5 of the key geriatric assessment tests. The number of patients for whom information on specific tests was available varied from 278 (4 geriatric assessment tests) to 388 (1 geriatric assessment test). Many patients were too impaired to complete even these basic tests; others were delirious and unable to answer, and some refused to be tested.

The percentage of patients with abnormal scores is illustrated in Table 2 ▶. A little more than 50% of the patients who took the test had an abnormal score (<24) on the Mini Mental State Examination, and 16.6% scored in the abnormal range (≥ 5) on the 15-point Geriatric Depression Scale. The physical performance test, an objective test for the ability to perform activities of daily living, was abnormal in 77.6% of those patients who took the test, and 58.9% achieved a score of 2 or less on the clock drawing test, which is a gross screen for executive function and cognition. An abnormal Duke Social Support Index score used to assess the adequacy of social support was seen in 94.6% of patients. The analysis of the CAGE measure revealed that 19.3% of the group who completed this assessment reported a positive history of problematic alcohol use. Approximately 75% of patients who underwent the Functional Activities Questionnaire had scores in the abnormal range. In addition, 48.6% of those with valid data on the self-rated health and mortality measure rated their health to be either fair or poor.

2.

Percentage of Elderly Self-Neglect Patients With Abnormal Scores in the Geriatric Assessment Battery: Houston, Tex, 1999–2004

| Assessment tool | Men, % | Women, % | Aged 65–75 y, % | Aged > 75 y, % | African American, % | White, % | Hispanic, % | Total No. of Group |

| Duke Social Support Index | 94.7 | 94.5 | 96.4 | 93.4 | 95.9 | 94.9 | 81.0 | 293 |

| Physical performance test | 80.5 | 74.6 | 69.0 | 81.2 | 79.6 | 74.8 | 64.7 | 278 |

| Functional Activities Questionnaire | 79.5 | 72.1 | 59.5 | 83.4 | 76.5 | 71.8 | 76 | 314 |

| Mini Mental State Examination | 48.2 | 53.2 | 38.0 | 60.5 | 61.3 | 43.3 | 39.1 | 388 |

| Clock drawing test | 52.9 | 64.8 | 45.7 | 71.6 | 72.0 | 49.6 | 52.2 | 355 |

| Geriatric Depression Scale | 19.6 | 13.5 | 20.9 | 11.8 | 14.3 | 14.1 | 30.0 | 341 |

| CAGE questionnaire | 27.9 | 10.7 | 21.5 | 11.6 | 18.4 | 10.6 | 12.0 | 311 |

Note. Change = Cut-Annoyed-Guilt-Eye Opener. See “Methods” section for descriptions of indexes and tests.

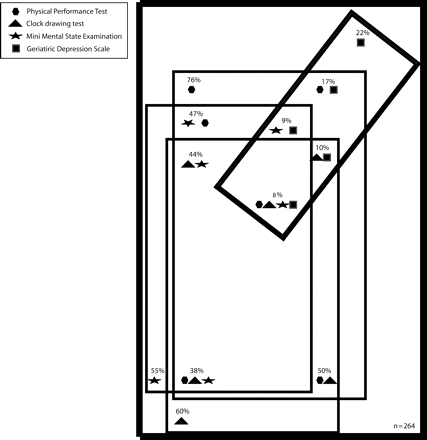

Figure 1 ▶ is a Venn diagram that depicts the number of patients with abnormal scores on 4 standard assessment tools: the Mini Mental State Examination, the Clock Drawing Test, the Geriatric Depression Scale, and the Physical Performance Test. Of the patients with abnormal scores, 264 provided data for all 4 of the tests. The Venn diagram illustrates the relationship among neuropsychiatric and functional impairments in persons who self-neglect. The diagram shows substantial overlap of the scores of 3 of the tests, except for the Geriatric Depression Scale. The Duke Social Support Index was abnormal in almost all of the patients (n = 250) who completed the assessment (N = 293) and is not shown in the Venn diagram.

FIGURE 1—

A Venn diagram of percentages of abnormal scores among elderly self-neglect patients: Houston, Tex, 1999–2004.

Note. A battery of geriatric assessment measures was administered to each patient and included the Mini Mental State Examination (cognition),15 the Geriatric Depression Scale (depression),16 the physical performance test (activities of daily living),17,18 the clock drawing test (executive function),19 and other test. See “Methods” section for more details.The Venn diagram illustrates the relationship among neuropsychiatric and functional impairments in persons who self-neglect.The diagram shows substantial overlap of the scores of 3 of the tests, except for the Geriatric Depression Scale.The Duke Social Support Index was abnormal in almost all of the patients (n = 250) who completed the assessment (N = 293) and is not shown in the Venn diagram.

A subsequent analysis was conducted to determine the degree to which the missing data were problematic. The group with data for all 5 geriatric assessment tests (n = 256) was compared with the available group data on each individual geriatric assessment test using a separate independent t test. The range of available data for the individual geriatric assessments was 278 (persons who took 4 geriatric assessment tests) to 388 (persons who took 1 geriatric assessment test). No significant differences between the means were found in these analyses.

DISCUSSION

Limitations

There are a number of limitations of this study. The database is a clinical one, and data were entered by a number of clinicians who made diagnoses based on their clinical judgment and not on a research protocol. Our sample included a large number of cognitively impaired individuals who were not able to provide the medical history or symptoms for the formulation of accurate diagnoses. But the geriatric medicine team was comprised of physicians, nurse practitioners, and a social worker all specifically trained in geriatric medicine, and the data were entered prospectively without specific hypotheses in mind.

There is an obvious referral bias attributable to a number of factors. Once a client is referred to the geriatric medicine team the adult protective services worker is required to participate in an interdisciplinary team meeting and to communicate and make decisions jointly with the geriatric medicine team clinicians, which is more labor intensive than the standard adult protective services procedures. So it is possible that those with higher case-loads did not refer clients because of time constraints. Some adult protective services workers believe that elder mistreatment is a social problem and may not have wanted to “medicalize” self-neglect. Many times the geriatric medicine team is called solely because the geriatricians make house calls. Some adult protective services workers only refer their most difficult clients. However, the demographics represented in our study’s sample are similar to the larger group reported to adult protective services.

Missing data were reported and may limit the remarks that we can make about the results; however, a analysis of the missing data showed these missing values to have a non-significant effect on the reported outcome measures.

Although findings consistent with executive dysfunction are noted, the only test used by the geriatric medicine team to study executive dysfunction was the 4-point Clock Drawing Test. The Research Committee of the American Neuropsychiatric Association asserted in a 2003 report that no single test is appropriate for assessing executive function and that a battery of tests is most appropriate.26 Also, the geriatric medicine team did not use any standard battery for assessing capacity; determinations were made on a patient-by-patient basis by the clinicians.

Conclusions

The data presented in this study comprise the largest and most detailed description of eldery persons who neglect themselves. Self-neglect among the elderly results in a failure to perform activities of daily living, which is manifested by some combination of poor hygiene, squalor in and outside their dwellings, a lack of utilities, an excess numbers of pets, and inadequate food stores. We found that 77.6% of patients had impairment in some of their activities of daily living evidenced by abnormal physical performance scores. Census data reveal that 38% of elderly persons in the United States experience impairment in activities of daily living.27 What then, distinguishes elderly persons who self-neglect from those who do not? The data suggest inadequate support services, as indicated by the large percentage of patients in this study who had low scores on the Duke Social Support Index. These support services often include medical care and assistance with bathing, dressing, home cleaning, laundry, and obtaining food. Some elderly persons who self-neglect simply lack access to support services, some refuse help, or some even when provided access to these services cannot complete the tasks necessary to obtain them.

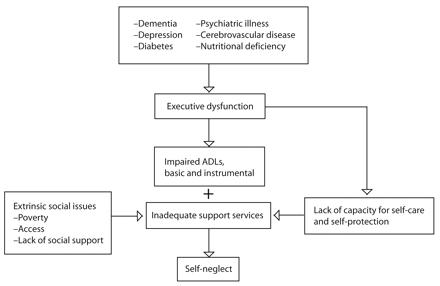

Our findings suggest that executive dysfunction may be at the root of many cases of self-neglect. Executive function is maintained by the frontal lobe. Specific regions of the frontal lobe are associated with behaviors that impair activities of daily living. When damage or disease affects the mesiofrontal region, apathy, distractibility, and failure to keep targeted goals results. When the orbitofrontal region is involved, persons display irritability, mood lability, and resistance to care—especially if they perceive the care as threatening. Lesions in the dorsofrontal region affect planning, hypothesis testing, judgment, and insight.28 The most common diagnoses in our study group included disorders that result in executive dysfunction such as dementia (15.9%), depression (14.3%), diabetes mellitus (25.2%), and cerebrovascular accident (17.7%). Even normal aging has been associated with executive dysfunction and may explain why there were some patients with no identified diagnoses.29 We believe elders who self-neglect are those with impairment in activities of daily living, who lack the needed support services, and who fail to recognize the danger. These older persons lose the cognitive capacity for self-protection. Of course, there are social issues beyond access to support such as lack of family, lack of transportation, and insufficient funds that likely also impact self-neglect. This theory is illustrated in the model depicted in Figure 2 ▶.

FIGURE 2—

Model of self-neglect among the elderly.

We suggest a case definition of elder self-neglect as a syndrome characterized by 1 or more disorders or normal aging that leads to executive dysfunction. The executive dysfunction results in an inability to perform activities of daily living in the setting of lack of access to or refusal of needed social or medical services. When coupled with the lack of capacity to recognize potentially unsafe living conditions, self-neglect ensues. This theory must be further studied using a battery of neuropsychiatric tests to determine executive function. Other studies are needed to determine the extent to which incapacity and specific medical disorders play a role and which interventions may prevent or delay self-neglect.

Academic groups such as the Texas Elder Abuse and Mistreatment Institute must intensify their research efforts. With the demographic imperative and the known incidence of disorders such as dementia and depression in older persons, the phenomenon of self-neglect must be studied further. Our work contributes to the establishment of a case definition for self-neglect and lays the groundwork for further description of the phenotype of self-neglecters. It is likely that the interventions and prevention strategies would vary by manifestation as well as by associated comorbidities. These strategies will require the development and testing of models to explain the relationships among physical, cognitive, and socioeconomic factors and the incidence and progression of self-neglect.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded in part by the Texas Department of Family Protective Services and the National Institutes of Health (grant P20RR20626).

The authors would like to thank Aanand Naik for his thoughtful review of the article and George Baum for his assistance with data management and data display. We want to thank all the clinicians of the Geriatrics Program at the Harris County Hospital District, especially Maria Vogel and Tziona Regev.

Human Participant Protection This study was approved by the Baylor College of Medicine’s institutional review board (H-13180).

Peer Reviewed

Contributors C. B. Dyer originated the study and supervised all aspects of its implementation. S. Pickens-Pace and J. Burnett assisted with the study, completed the analyses, and contributed to the writing. J. S. Goodwin assisted with the study design and contributed to the writing. P.A. Kelly synthesized the analyses and contributed to the writing.

References

- 1.Pavlik VN, Hyman DJ, Festa NA, Bitondo Dyer C. Quantifying the problem of abuse and neglect in adults—analysis of a statewide database. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2001;49:45–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lachs MS, Williams C, O’Brien S, Hurst L, Horwitz R. Risk factors for reported elder abuse and neglect: a nine-year observational cohort study. Gerontologist. 1997;37:469–474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fulmer T, Paveza G, Abraham I, Fairchild S. Elder neglect assessment in the emergency department. J Emerg Nurs. 2000;26:436–443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.The National Center on Elder Abuse, American Public Human Services Association. The National Elder Abuse Incidence Study: Final Report. Washington, DC: Administration for Children and Families and Administration on Aging, US Department of Health and Human Services; 1998. Available at: http://www.aoa.gov/eldfam/Elder_Rights/Elder_Abuse/ABuseReport_Full.pdf. Accessed July 21, 2007.

- 5.The National Center on Elder Abuse. A Response to the Abuse of Vulnerable Adults: The 2000 Survey of State adult protective services. Available at: http://www.elderabusecenter.org/pdf/research/apsreport030703.pdf. Accessed July 21, 2007.

- 6.Lachs MS, Williams CS, O’Brien S, Pillemer KA, Charlson ME. The mortality of elder mistreatment. JAMA. 1998;280:428–432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gruenberg EM, Brandon S, Kasius RV. Identifying cases of the social breakdown syndrome. Milbank Mem Fund Q. 1966;44(suppl):150–155. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Macmillan D, Shaw P. Senile breakdown in standards of personal and environmental cleanliness. Br Med J. 1966;2:1032–1037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Clark AN, Mankikar GD, Gray I. Diogenes syndrome: a clinical study of gross neglect in old age. Lancet. 1975;1:366–368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Halliday G, Bannerjee S, Philpot M, Macdonald A. Community study of people who live in squalor. Lancet. 2000;355:882–886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hurley M, Scallan E, Johnson H, De La Harpe D. Adult service refusers in the greater Dublin area. Ir Med J. 2000;93:208–211. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Snowden LR. The peculiar successes of community psychology: service delivery to ethnic minorities and the poor. Am J Community Psychol. 1987;15:575–586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wrigley M, Loane R. Consultation-liaison referrals to the north Dublin old age psychiatry service. Ir Med J. 1991;84:89–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lachs MS, Williams C, O’Brien S, Hurst L, Horwitz R. Older adults. An 11-year longitudinal study of adult protective service use. Arch Intern Med. 1996; 156:449–453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. “Mini-mental state.” A practical method for grading cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res. 1975;12: 189–198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yesavage JA, Brink TL, Rose TL, et al. Development and validation of a geriatric depression screening scale: a preliminary report. J Psychiatr Res. 1983;17: 37–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brown M, Sinacore DR, Binder EF, Kohrt WM. Physical and performance measures for the identification of mild to moderate frailty. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2000;55:M350–M355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sherman SE, Reuben D. Measures of functional status in community-dwelling elders. J Gen Intern Med. 1998;13:817–823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tuokko H, Hadjistavropoulos T, Miller JA, Beattie BL. The Clock Test: a sensitive measure to differentiate normal elderly from those with Alzheimer disease. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1992;40:579–584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Juva K, Makela M, Erkinjuntti T, et al. Functional assessment scales in detecting dementia. Age Ageing. 1997;26:393–400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pfeffer RI, Kurosaki TT, Harrah CH Jr, Chance JM, Filos S. Measurement of functional activities in older adults in the community. J Gerontol. 1982;37: 323–329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Idler EL, Angel RJ. Self-rated health and mortality in the NHANES-I Epidemiologic Follow-up study. Am J Public Health. 1990;80:446–452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Strodl E, Kenardy J, Aroney C. Perceived stress as a predictor of the self-reported new diagnosis of symptomatic CHD in older women. Int J Behav Med. 2003; 10:205–220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Landerman R, George LK, Campbell RT, Blazer DG. Alternative models of the stress buffering hypothesis. Am J Community Psychol. 1989;17:625–642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ewing JA. Detecting alcoholism. The CAGE questionnaire. JAMA. 1984;252:1905–1907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Royall DR, Lauterbach EC, Cummings JL, et al. Executive control function: a review of its promise and challenges for clinical research. A report from the Committee on Research of the American Neuropsychiatric Association. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2002; 14:377–405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Federal Interagency Forum on Aging Related Statistics. Older Americans 2004: Key Indicators of Well-Being. Available at: http://www.agingstats.gov/agingstatsdotnet/Main_Site/Data/2004_Documents/entire_report.pdf. Accessed July 21, 2007.

- 28.Royall DR, Palmer R, Chiodo LK, Polk MJ. Executive control mediates memory’s association with changes in instrumental activities of daily living: the Freedom House Study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53: 11–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Royall DR, Palmer R, Chiodo LK, Polk MJ. Declining executive control in normal aging predicts change in functional status: the Freedom House Study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2004;52:346–352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]