Summary

The conservation of structure across paralog proteins promotes alternative protein-ligand associations often leading to side effects in drug-based inhibition. However, sticky packing defects are typically not conserved across paralogs, making them suitable targets to reduce drug toxicity. This observation enables a strategy for the design of highly specific inhibitors involving ligands that wrap nonconserved packing defects. The selectivity of these inhibitors is evidenced in affinity assays on a cancer-related pharmacokinome: a powerful inhibitor is redesigned by using the wrapping technology to enhance its selectivity and affinity for a target kinase. In this way, the packing defects of a soluble protein may be used as selectivity filters for drug design.

Introduction

The function of soluble proteins requires stable folds that often rely on associations to maintain their integrity (Dunker et al., 2002;Huber, 1979;Verkhivker et al., 2003). Isolated structures with packing defects arising as poorly protected hydrogen bonds do not typically prevail in water (Fernández, 2004;Fernández and Berry, 2004). Here, we show that packing defects may be targeted to develop a novel, to our knowledge, type of highly selective inhibitor. Furthermore, the inspection of protein-inhibitor complexes of reported structure (Fauman et al., 2003;Stevens, 2004;Wlodawer and Vondrasek, 1998;Arkin and Wells, 2004;Katz et al., 2000;Steinmetzer et al., 2001) supports the design concept of an inhibitor as a wrapper of packing defects and of a packing defect as a selectivity filter.

While structural conservation holds across paralogs, packing defects are often not conserved (Fernández and Berry, 2004). Thus, side effects resulting from off-target ligand binding may be minimized by selectively targeting nonconserved packing defects with the guidance of a measure of packing similarity, as shown in this work.

Structural descriptors of protein binding sites, such as hydrophobicity (Nicholls et al., 1991), curvature (Liang et al., 1998), and accessibility (Lee and Richards, 1971) are routinely used to guide inhibitor design. However, upon examination of the 814 nonredundant protein-inhibitor PDB complexes, it is apparent that in 488 of them, the binding cavity has an average hydrophobicity not significantly higher than the rest of the surface. In such cases, ligand affinity is attributed to the intermolecular hydrogen-bonding propensities of the inhibitor, inferred from protein-substrate transition-state mimetics (Wlodawer and Vondrasek, 1998;Arkin and Wells, 2004;Katz et al., 2000;Steinmetzer et al., 2001). However, charge screening in water renders putative intermolecular hydrogen bonds unlikely promoters of protein-ligand association, unless other factors are present at the interface to foster water removal (Fernández and Scheraga, 2003).

One such factor has been recently identified. We have reported (Fernández, 2004;Fernández and Berry, 2004,Fernández and Scheraga, 2003) that packing defects in proteins, the so-called dehydrons (Fernández and Berry, 2004;Deremble and Lavery, 2005), or underwrapped hydrogen bonds, constitute sticky sites with a propensity to become dehydrated. The term ‘‘wrapping’’ indicates a clustering of nonpolar groups framing an anhydrous microenvironment. Dehydrons are signaled by insufficient intramolecular wrappers and promote protein-ligand associations that ‘‘correct’’ packing defects (Fernández and Scheraga, 2003;Deremble and Lavery, 2005). Their stickiness arises from the charge-screening reduction resulting from bringing nonpolar groups into proximity: water exclusion enhances and stabilizes preformed electrostatic interactions. A few (<7) nonpolar groups wrapping a hydrogen bond simply prevent the hydration of the amide and carbonyl, but a sufficient number of wrappers, while making hydration thermodynamically costly, introduce a compensation by enhancing the stability of the hydrogen bond (Fernández and Scott, 2003).

We start by showing that in most PDB protein-inhibitor complexes, the ligand is in effect a wrapper of packing defects in the protein, although it was not purposely designed to fulfill this role. In this way, the design concept of ligand as a dehydron wrapper is supported by reexamination of structural data. These preliminary data pave the way to introduce a wrapping technology in drug design. A proof of principle is provided by demonstrating experimentally that targeting dehydrons that are not conserved across paralogs becomes a useful strategy to enhance binding selectivity. Thus, we take advantage of packing differences to selectively modify a powerful multiple-target inhibitor to achieve a higher specificity toward a particular target.

Results

Ligands as Dehydron Wrappers in Protein-Inhibitor Complexes

The interfaces of the 814 protein-inhibitor PDB complexes were reexamined to determine whether inhibitors were ‘‘dehydron wrappers,’’ that is, whether nonpolar groups of inhibitors penetrated the desolvation domain of dehydrons. This feature was found in 631 complexes, and it was invariably found in the 488 complexes in which the binding cavity presented average or no surface hydrophobicity. This situation is illustrated in Figures 1 and 2 for the HIV-1 protease ( Wlodawer and Vondrasek, 1998 ; Munshi et al., 1998 ) and the urokinase-type plasminogen activator ( Katz et al., 2000 ), respectively. The inhibitor contribution to improve the protein packing is not fortuitous since the substrate must be anchored and water must be expelled from the enzymatic site. Strikingly, the wrapping of dehydrons is not purposely attempted in current drug design.

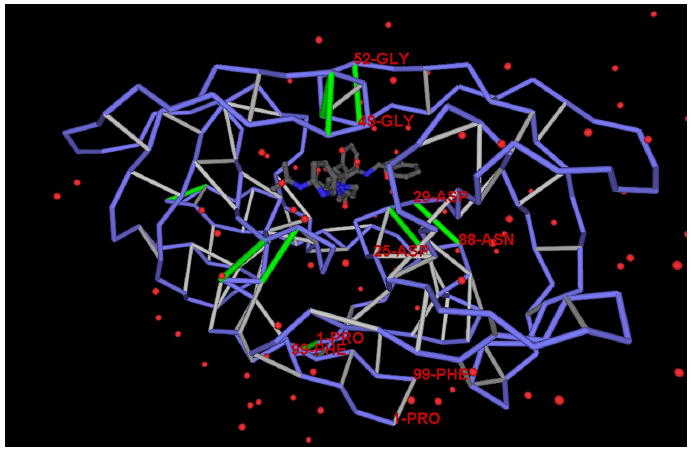

Figure 1. Structure of HIV-1 Protease with an Inhibitor Acting as a Dehydron Wrapper.

A dehydron is identified by determining the extent of the intramolecular desolvation, ρ, of the hydrogen bond, quantified as the number of nonpolar groups within its desolvation domain. The desolvation domain consists of two intersecting balls of radii 6.4 Å centered at the α-carbons of the paired residues. Most (~92% of the PDB entries) stable folds have at least two-thirds of backbone hydrogen bonds with ρ = 26.6 ± 7.5. Dehydrons are hydrogen bonds with ρ ≤19 (their r value is below the mean minus one Gaussian dispersion). The figure shows the Indinavir (Crixivan) inhibitor crystallized in complex with HIV-1 protease (PDB: 2BPX). The packing defects of the dimeric protease are shown in their spatial relation to the inhibitor position. The protein chain backbone is represented by blue virtual bonds joining α-carbons, well-wrapped backbone hydrogen bonds are shown as light-gray segments joining the α-carbons of the paired residues, and dehydrons are shown as green segments. The figure shows in detail the protease cavity, the pattern of packing defects, and the inhibitor positioned as a dehydron wrapper.

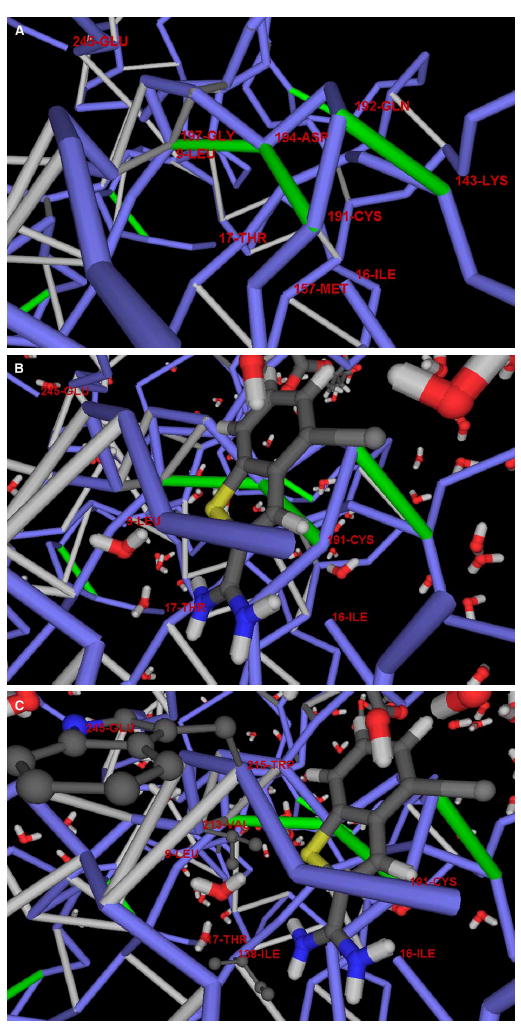

Figure 2. Inhibitor as a Wrapper of Packing Defects in the Urokinase-Type Plasminogen Activator.

(A) Detail of the dehydron pattern of the protein cavity.

(B) The inhibitor-protein complexation revealing the position of the inhibitor as a wrapper of the packing defects in the cavity. The only dehydrons in a concave region of the protein surface are: Cys191-Asp194, Asp194-Gly197, and Gln192-Lys143. Upon complexation, the inhibitor wraps all three dehydrons, contributing six nonpolar groups to their desolvation domains.

(C) Hydrophobic residues in the cavity region and their mismatch against polar moieties in the inhibitor across the protein-ligand interface. There are three nonpolar residues in the rim of the protein cavity, Ile138, Val213, and Trp215, but none is engaged in hydrophobic interactions with the inhibitor.

The Merck inhibitor Indinavir (Crixivan) bound to the functionally dimeric HIV-1 protease (PDB: 2BPX) is shown in Figure 1 ( Wlodawer and Vondrasek, 1998 ; Munshi et al., 1998 ). The dehydrons in the protease are marked in green. On each monomer, these dehydrons are backbone hydrogen bonds involving the following residue pairs: Ala28-Arg87, Asp29-Asn88, Gly49-Gly52, and Gly16-Gln18. The cavity associated with substrate binding contains the first three dehydrons, with dehydrons 49–52 located in the flap and dehydrons 28–87 and 29–88 positioned next to the catalytic site (Asp25), to anchor the substrate. This ‘‘sticky track’’ determined by dehydrons 28–87 and 29–88 is required to align the substrate peptide across the cavity, as needed for nucleophilic attack by the Asp25s. The flap, on the other hand, must have an exposed and hence labile hydrogen bond needed to confer the flexibility associated with the gating mechanism. The lack of protection on the flap (49–52) hydrogen bond becomes the reason for its stickiness, as the bond can be strengthened by the exogenous removal of surrounding water. The positioning of all three dehydrons in the cavity (six in the dimer) promotes inhibitor association.

Indinavir is a wrapper of packing defects in the enzymatic cavity: it contributes 12 desolvating groups to the 49–52 hydrogen bond, 10 to the 28–87 hydrogen bond, and 8 to the 29–88 hydrogen bond. All functionally relevant residues are either polar or expose the polarity of the peptide backbone (Asp25, Thr26, Gly27, Ala28, Asp29, Arg87, Asn88, Gly49, Gly52), and, thus, they are not themselves promoters of protein-ligand association. The strategic position of dehydrons involving these residues in their microenvironments becomes a decisive factor in promoting water removal or charge descreening required in facilitating the enzymatic nucleophilic attack.

Figure 2 shows an inhibitor acting as a wrapper of packing defects in its complexation with the urokinase-type plasminogen activator (PDB: 1C5W), a protease associated with tumor metastasis and invasion ( Katz et al., 2000 ). Figures 2A and 2 B reveal dehydrons Cys191-Asp194, Asp194-Gly197, and Gln192-Lys143 in the protein cavity. Strikingly, none of the hydrophobic residues in the cavity contributes to the inhibitor binding (Figure 2C ).

Nonconserved Packing Defects as Highly Specific Targets

Central to drug design is the minimization of toxic side effects. Because paralog proteins are likely to share common domain structures (Mount, 2001), the possibility of multiple binding partners for a given protein inhibitor arises, unless nonconserved features are specifically targeted. This problem may be circumvented by targeting dehydrons, because, in contrast to the fold, the wrapping is generally not conserved (Fernández and Berry, 2004).

To determine whether dehydron targeting is likely to reduce side effects, we first investigated the extent of the conservation of dehydrons across human paralogs in the PDB. The paralogs for every crystallized protein-inhibitor complex were identified, and dehydron patterns at binding cavities were compared. A 30% minimal sequence alignment was required for paralog identification. Packing defects were found to be a differentiating marker in paralogs of 527 out of the investigated 631 proteins crystallized in complex with inhibitors. A protein chain is often reported in complexes with different inhibitors.

The PDB contains 440 redundancy-free pairs of human paralogs. Of these, 308 involve some of the 527 proteins containing binding dehydrons. In 269 pairs, the intramolecular wrapping at the binding cavity differs in the location or presence of at least 1 dehydron, and, in 203 pairs, the difference extends to 2 or more dehydrons. Thus, the probability of avoiding cross reactivity by selectively wrapping packing defects is estimated at 88% (269 pairs out of 308).

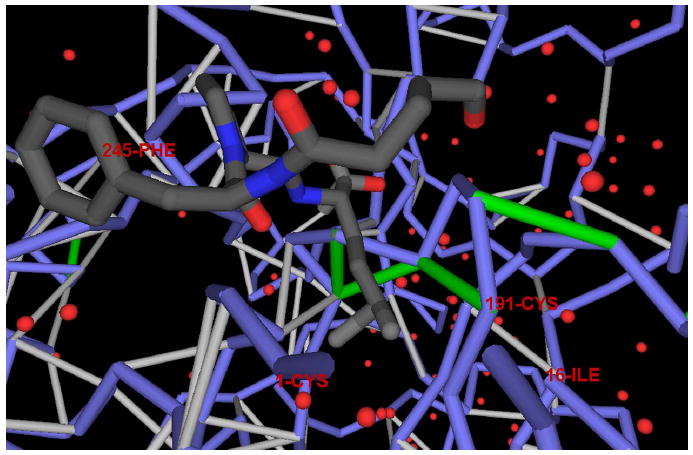

For instance, α-thrombin (PDB: 1A3E) (Zdanov et al., 1993), a paralog of the plasminogen activator (PDB: 1C5W), shares a common domain structure, but a different dehydron pattern (Figure 3). While the inhibitor of the α-thrombin is a wrapper of cavity dehydrons (Figure 3), additional specificity would have been gained if the inhibitor had been tailored to target the unique dehydron pattern of the cavity (compare Figures 2A and 3). Specifically, the Ser195-Gly197 dehydron present in α-thrombin becomes intramolecularly well-wrapped in the plasminogen activator (Figures 2A and 3).

Figure 3. The Nonconserved Wrapping across Paralogs Sharing Common Folds with Drug-Targeted Proteins.

Dehydron pattern in α-thrombin (PDB: 1A3E), a paralog of the plasminogen activator (PDB: 1C5W) sharing a common domain structure, but different wrapping, together with the location of the inhibitor within the complex. The figure reveals the role of the inhibitor as a wrapper of the packing defects in the cavity. Notice the difference in the dehydron pattern of the cavity, distinguishing the α-thrombin from its paralog shown in Figure 2.

Proof of Principle: Using Wrapping Technology to Enhance Drug Specificity

We now provide a proof of principle of the enhanced selectivity achieved by using wrapping technology. Because of the evolutionary proximity of kinases (Manning et al., 2002), side effects arising from off-target ligand binding often arise with kinase inhibitors, especially in cancer therapy (Fabian et al., 2005). Nearly all kinase inhibitors target the adenosine triphosphate (ATP) binding pocket, a highly conserved structural feature across the human kinome (Cohen et al., 2005). Thus, a need arises to sharpen the binding affinity within the pharmacokinome associated with a specific drug. For instance, the selective inhibition of the Brc-Abl (Abelson tyrosine kinase), the fusion product of a chromosomal translocation, is crucial to treat chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) (Schindler et al., 2000). Brc-Abl has been proven to be a target for the potent inhibitor Gleevec (Schindler et al., 2000), but not its only target (Fabian et al., 2005). Of the alternative targets with reported structure, the C-kit tyrosine kinase has been recognized as a binding partner, making Gleevec a therapeutic agent for colorectal cancer (Attoub et al., 2002;Skene et al., 2004). In addition, Gleevec binds tightly to the lymphocyte kinase (Lck) (Perlmutter et al., 1988). Thus, we sought to modify Gleevec to improve its selectivity for Brc-Abl by targeting dehydrons not conserved across paralogs.

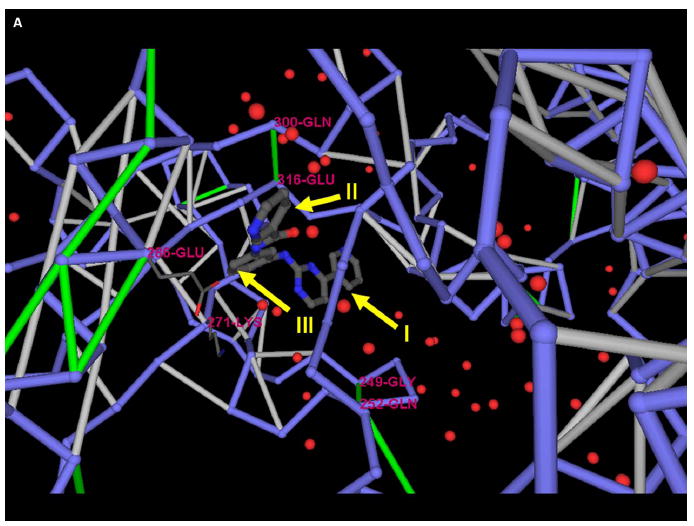

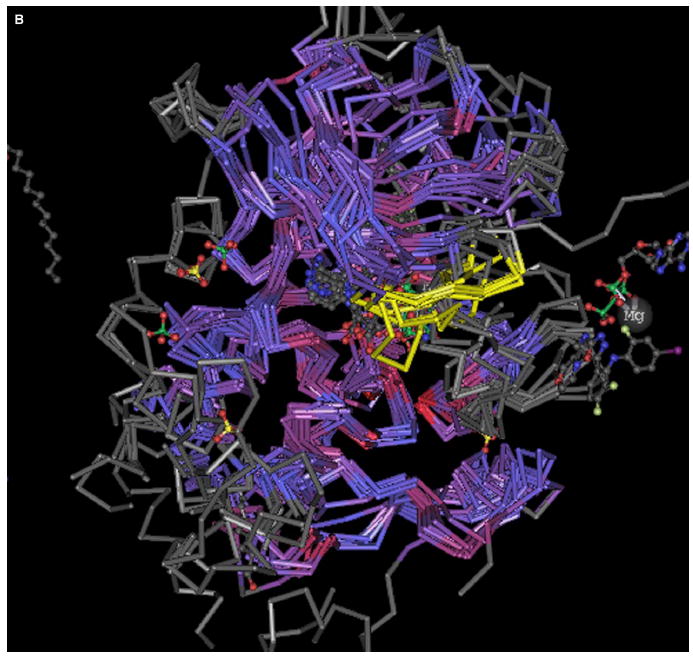

The protein-inhibitor complex (PDB: 1FPU) (Figure 4A ), reveals three electrostatic interactions in Brc-Abl, the dehydrons Gly249-Gln252 and Gln300-Glu316 and the salt bridge Lys271-Glu286, that can be better wrapped by methylating Gleevec at the positions indicated. Thus, methylation at positions I, II, and III would contribute to improve the wrapping of dehydrons 249–252 and 300–316 and the salt bridge 271–286, respectively. A structural alignment of the paralogs of Brc-Abl was performed by using the program Cn3D (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/structure/CN3D/cn3d.shtml) to investigate the microenvironment conservation for these intramolecular interactions. The six kinases reported in the PDB that aligned with Brc-Abl are: C-kit (PDB: 1T45), Lck (PDB: 3LCK), Pdk1 kinase (PDB: 1UVR), Cdc42-associated Tyr kinase Ack1 (PDB: 1U54), epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) kinase (PDB: 1M17), and the checkpoint kinase Chk1 (PDB: 1IA8). The alignment is shown in Figure 4B. Dehydron 249–252 (crankshaft-like kink marked in yellow on Figure 4B) is not conserved in any of the six paralogs of Brc-Abl, while dehydron 300–316 becomes well-wrapped in the paralogs. On the other hand, the microenvironment of the salt bridge 271–286 is conserved.

Figure 4. Modifications of Gleevec Geared at Improving Selectivity and Affinity for Brc-Abl.

(A) Three possible sites for Gleevec methylation (I–III) aimed at selectively improving the wrapping of packing defects of Brc-Abl (PDB: 1FPU).

(B) Structural alignment of Brc-Abl and its six paralogs by using the program Cn3D. The yellow region corresponds to a β hairpin in Brc-Abl covering amino acids 247–257.

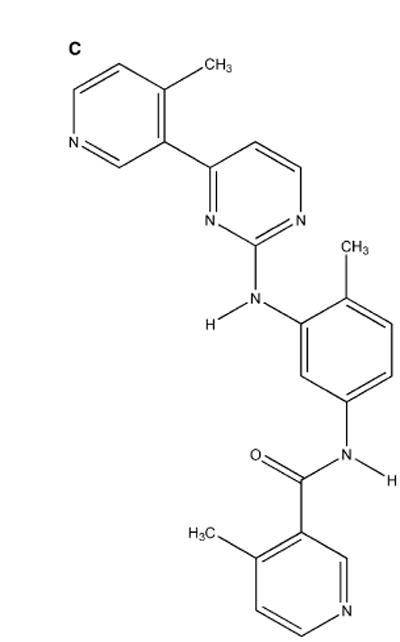

(C) The modified Gleevec-based molecule methylated at sites I and II and assayed in vitro in this study.

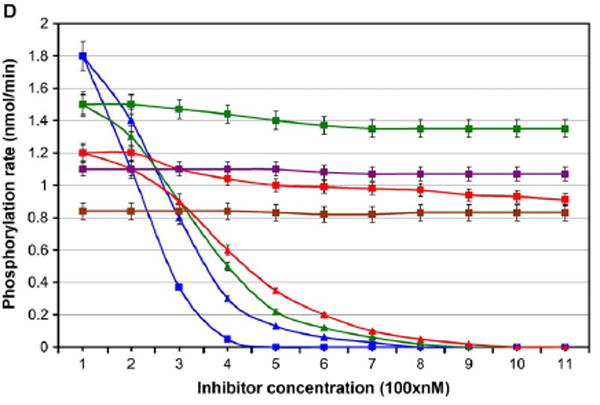

(D) Rate of phosphorylation of Brc-Abl (blue), C-kit (green), Lck (red), Chk1 (purple), and Pdk1 (brown) in the presence of Gleevec (triangles) and in the presence of the I-, II-methylated modified Gleevec (squares). The latter compound was designed to better wrap the nonconserved dehydrons in Brc-Abl. Within the means of detection, the kinase phosphorylation rates do not vary appreciably in the range of 0–100 nM inhibitor concentration. Error bars represent the dispersion in measurements over ten repetitions of each kinetic assay.

In order to enhance affinity and selectivity for Brc-Abl, we modified the inhibitor methylating at positions I and II (Figure 4C ) (Li et al., 2004). To test whether the specificity and affinity for Brc-Abl improved, we conducted a spectrophotometric assay to measure the phosphorylation rate of peptide substrates (Schindler et al., 2000; Timokhina et al., 1998;Perlmutter et al., 1988;Zhao et al., 2002;Le Good et al., 1998 ) in the presence of the kinase inhibitor at different concentrations. As indicated in Figure 4D, the inhibition of the specificity Brc-Abl by the wrapper of the 249–252 and 300–316 dehydrons (the I, II methylation product) improved over Gleevec levels. Furthermore, the inhibitory impact of the dehydron wrapper became selective for Brc-Abl vis-à-vis C-kit and Lck. Dehydrons 249–252 and 300–316 are absent in the latter kinases, and, consistently, the drug designed to better wrap them has a very low inhibitory impact against C-kit and Lck. Finally, neither Gleevec nor its modified version showed detectable inhibitory impact on the remaining paralogs, Chk1 and Pdk1, for which substrate peptides have been reported.

The results expounded on in Figure 4 substantiate our claim that nonconserved packing defects may be used as selectivity filters in drug design.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this study substantiates a novel concept in inhibitor design: packing defects may be targeted by ligands designed to wrap them or shield them from water attack. Since structure packing is typically not conserved across paralog proteins, the inhibitory impact resulting from applying the wrapping technology is likely to be highly selective, turning packing defects into selectivity filters. Conversely, the measure of packing similarity used to lead the inhibitor design may also be used to implement a multidimensional multiple-target approach to drug therapy. Future research is expected to explore this possibility.

The wrapping technology introduced in this work has biological implications since it hinges on a novel, to our knowledge, molecular descriptor of the structure/ function multivalued relation. Thus, as noted previously (Fernández and Berry, 2004), the packing constitutes a molecular dimension explored in evolution to foster new functionalities within an invariant fold. This work reveals how this evolutionary footprint may be targeted by the drug designer in order to enhance selectivity.

Experimental Procedures

Structure-Based Dehydron Identification

Packing defects in the form of dehydrons or underwrapped backbone hydrogen bonds may be identified from the atomic coordinates of a protein structure in a single or multidomain chain or in a protein complex in a PDB entry, according to simple tenets (Fernández and Berry, 2004): (1) The extent of intramolecular hydrogen bond desolvation, ρ, in the monomeric structure may be quantified by determining the number of nonpolar groups (carbonaceous, not covalently bonded to an electrophilic atom) contained within a desolvation domain. (2) The desolvation domain is defined as two intersecting balls of fixed radii centered at the α-carbons of the residues paired by the backbone amide-carbonyl hydrogen bond (Fernández and Berry, 2004). (3) The extent of desolvation of an intramolecular hydrogen bond within a protein-ligand or protein-protein complex requires that the count include nonpolar groups from the monomer as well as those from its binding partner(s). The statistics of hydrogen bond wrapping vary according to the desolvation radius adopted, but the tails of the distribution invariably single out the same dehydrons in a given structure over a 6.2–7 Å range in the adopted desolvation radius. In this work, the value of 6.4 Å was adopted.

In most (~92% of the PDB entries) stable protein folds, at least two-thirds of the backbone hydrogen bonds are wrapped on average by ρ = 26.6 ± 7.5 nonpolar groups (or 14.0 ± 3.7 counting only side chain groups and excluding those from the hydrogen bonded residue pair) (Fernández and Scheraga, 2003). Dehydrons are here defined as hydrogen bonds whose extent of wrapping lies in the tails of the distribution, i.e., with 19 or fewer nonpolar groups in their desolvation domains (their ρ value is below the mean minus one Gaussian dispersion). Dehydrons are dominant factors driving association in 38% of the PDB complexes (the number of dehydrons per 1000 Å2 at protein-protein interfaces is more than 3/2 the average density on individual monomers). Furthermore, dehydrons constitute significant factors (interface dehydron density larger than average) in 92.9% of all PDB complexes ( Fernández and Scheraga, 2003;Deremble and Lavery, 2005).

Given the inherent stickiness of packing defects in soluble proteins (Fernández, 2004;Fernández and Scott, 2003), and the fact that interfacial water removal from a concave or flat region of the protein surface entails far less thermodynamic work than removal from a convex water-clathrated region (Liang et al., 1998), we may conclude that dehydrons in cavities are suitable targets for ligand design. These structural features become of paramount importance when the hydrophobicity of the cavity (Nicholls et al., 1991) is not significantly higher than the average for a soluble protein surface (Fernández and Scheraga, 2003).

Spectrophotometric Kinetic Assay

To determine the level of selectivity of drug inhibitors designed by adopting the wrapping technology, kinetic assays of the inhibition of multiple kinases have been conducted. To measure the rate of phosphorylation due to kinase activity in the presence of inhibitors, a standard spectrophotometric assay has been adopted (Schindler et al., 2000) in which the adenosine diphosphate production is coupled to the NADH oxidation and determined by absorbance reduction at 340 nm. Reactions were carried out at 35ºC in 500 μl buffer (100 mM Tris-HCl, 10 mM MgCl2, 0.75 mM ATP, 1 mM phosphoenol pyruvate, 0.33 mM NADH, 95 U/ml pyruvate kinase). The adopted peptide substrates (Invitrogen/Biaffin) for kinase phosphorylation are: AEEEIYGEFEAKKKKG for unphosphorylated Brc-Abl (Schindler et al., 2000), KVVEEINGNNYVYIDPTQLPY for C-kit (Timokhina et al., 1998), GLARLIEDNEYTAREGAKFPI for Lck (Perlmutter et al., 1988), GCSPALKRSHSDSLDHDIFQL for Chk1 (Zhao et al., 2002), and EGLGPGDTTSTFCGTPNYIAP for Pdk1 (Le Good et al., 1998).

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by National Institutes of Health grant 1R01 GM072614-01A1 from the National Institutes of General Medical Sciences (NIGMS). Earlier portions of the work were supported by INGEN, the Indiana Genomics Initiative, a program made possible through a contribution from the Lilly Endowment, and by an unrestricted grant from Eli Lilly and Company.

References

- Arkin MR, Wells JA. Small-molecule inhibitors of protein-protein interactions: progressing towards the dream. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2004;3:301–317. doi: 10.1038/nrd1343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Attoub S, Rivat C, Rodrigues S, Van Borexlaer S, Bedin M, Buyneel E, Louvet C, Kornprobst M, Andre T, Mareel M, et al. The c-kit tyrosine kinase inhibitor STI-571 for colorectal cancer therapy. Cancer Res. 2002;62:4879–4883. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen MS, Zhang C, Shokat KM, Taunton J. Structural Bioinformatics-based design of selective, irreversible kinase inhibitors. Science. 2005;308:1318–1321. doi: 10.1126/science1108367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deremble C, Lavery R. Macromolecular recognition. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2005;15:171–175. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2005.01.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunker KA, Brown C, Obradovic Z. Indentification and function of usefully disordered proteins. Adv Protein Chem. 2002;62:25–49. doi: 10.1016/s0065-3233(02)62004-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fabian MA, Biggs WH, Treiber DK, Atteridge CE, Azimioara MD, Benedetti MG, Carter TA, Ciceri P, Edeen PT, Floyd M, et al. A small molecule-kinase interaction map for clinical kinase inhibitors. Nat Biotechnol. 2005;23:329–336. doi: 10.1038/nbt1068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fauman EB, Hopkins A, Groom C. In: Structural bioinformatics in drug discovery In Structural Bioinformatics. Bourne P, Weissig H, editors. New York: Wiley-Liss; 2003. pp. 477–497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernández A. Keeping dry and crossing membranes. Nat Biotechnol. 2004;22:1081–1085. doi: 10.1038/nbt0904-1081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernández A, Berry RS. Molecular dimension explored in evolution to promote proteomic complexity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:13460–13465. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0405585101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernández A, Scheraga HA. Insufficiently dehydrated hydrogen bonds as determinants of protein interactions. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:113–118. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0136888100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernández A, Scott RS. Adherence of packing defects in soluble proteins. Phys Rev Lett. 2003;91:018102. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.91.018102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huber R. Conformational flexibility in protein molecules. Nature. 1979;280:538–539. doi: 10.1038/280538a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katz BA, Mackman R, Luong C, Radika K, Martelli A, Sprengeler PA, Wang J, Chan H, Wong L. Structural basis for selectivity of a small molecule, S1-Binding, submicromolar inhibitor of urokinase-type plasminogen activator. Chem Biol. 2000;7:299–307. doi: 10.1016/s1074-5521(00)00104-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Good JA, Ziegler WH, Parekh DB, Alessi DR, Cohen P, Parker PJ. Protein kinase C isotypes controlled by phosphoinositide 3-kinase. Science. 1998;281:2042–2045. doi: 10.1126/science.281.5385.2042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee B, Richards FM. The interpretation of protein structures: estimation of static accessibility. J Mol Biol. 1971;55:379–400. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(71)90324-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li JJ, Johnson D, Sliskovic D, Roth B. Contemporary Drug Synthesis . Hoboken, NJ: Wiley Interscience; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Liang J, Edelsbrunner H, Woodward C. Anatomy of protein pockets and cavities: measurement of binding site geometry and implications for ligand design. Protein Sci. 1998;7:1884–1897. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560070905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manning G, Whyte DB, Martinez R, Hunter T, Sudarsanam S. The protein kinase complement of the human genome. Science. 2002;298:1912–1934. doi: 10.1126/science.1075762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mount DW. Bioinformatics . Cold Spring Harbor, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Munshi S, Chen Z, Li Y, Olsen DB, Fraley ME, Hungate RW, Kuo LC. Rapid X-ray diffraction analysis of HIV-1 protease-inhibitor complexes: inhibitor exchange in single crystals of the bound enzyme. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 1998;54:1053–1060. doi: 10.1107/s0907444998003588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicholls A, Sharp KA, Honig B. Protein folding and association: insights from the interfacial and thermodynamic properties of hydrocarbons. Proteins. 1991;11:281–296. doi: 10.1002/prot.340110407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perlmutter RM, Marth JD, Lewis DB, Peet R, Ziegler SF, Wilson CB. Structure and expression of lck transcripts in human lymphoid cells. J Cell Biochem. 1988;38:117–126. doi: 10.1002/jcb.240380206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schindler T, Bornmann W, Pellicena P, Miller WT, Clarkson B, Kuriyan J. Structural mechanism for STI-571 inhibition of Abelson tyrosine kinase. Science. 2000;289:1938–1942. doi: 10.1126/science.289.5486.1938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skene RJ, Kraus ML, Scheibe DN, Snell GP, Zou H, Sang BC, Wilson KP. Structural basis for autoinhibition and STI-571 inhibition of C-kit tyrosine kinase. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:31655–31663. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M403319200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinmetzer T, Hauptmann J, Sturzebecher J. Advances in the development of thrombin inhibitors. Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 2001;10:845–864. doi: 10.1517/13543784.10.5.845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stevens RC. Long live structural biology. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2004;11:293–295. doi: 10.1038/nsmb0404-293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Timokhina I, Kissel H, Stella G, Besmer P. Kit signaling through PI 3-kinase and Src kinase pathways: an essential role for Rac1 and JNK activation in mast cell proliferation. EMBO J. 1998;17:6250–6262. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.21.6250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verkhivker G, Bouzida D, Gehehaar D, Rejto P, Freer ST, Rose P. Simulating disorder-order transition in molecular recognition of unstructured proteins: where folding meets binding. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:5148–5153. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0531373100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wlodawer A, Vondrasek J. Inhibitors of HIV-1 protease: a major success of structure-assisted drug design. Annu Rev Biophys Biomol Struct. 1998;27:249–284. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biophys.27.1.249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zdanov A, DiMaio J, Konishi Y, Li Y, Wu X, Edwards BF, Martin PD, Cygler M. Crystal structure of the complex of human α-thrombin and nonhydrolyzable bifunctional inhibitors, hirutonin-2 and hirutonin-6. Proteins. 1993;17:252–265. doi: 10.1002/prot.340170304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao H, Watkins JL, Piwnica-Worms H. Disruption of the checkpoint kinase 1/cell division cycle 25A pathway abrogates ionizing radiation-induced S and G2 checkpoints. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:14795–14800. doi: 10.1073/pnas.182557299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]