Abstract

Hyperoxia and pulmonary infections are well known to increase the risk of acute and chronic lung injury in newborn infants, but it is not clear whether hyperoxia directly increases the risk of pneumonia. The purpose of this study was to examine: 1) the effects of hyperoxia and antioxidant enzymes on inflammation and bacterial clearance in mononuclear cells; and 2) developmental differences between adult and neonatal mononuclear cells in response to hyperoxia. Mouse macrophages were exposed to either room air (RA) or 95% O2 for 24 h and then incubated with P. aeruginosa (PA). After 1 h, bacterial adherence, phagocytosis and macrophage inflammatory protein (MIP)-1α production were analyzed. Bacterial adherence increased 5.8 fold (P<0.0001), phagocytosis decreased 60% (P<0.05), and MIP-1α production increased 49% (P<0.05) in response to hyperoxia. Overexpression of MnSOD or catalase significantly decreased bacterial adherence by 30.5%, but only MnSOD significantly improved bacterial phagocytosis and attenuated MIP-1α production. When monocytes from newborns and adults were exposed to hyperoxia, phagocytosis was impaired in both groups. However, adult monocytes were significantly more impaired than neonatal monocytes. Data indicate that hyperoxia significantly increases bacterial adherence while impairing function of mononuclear cells, with adult cells more impaired than neonatal cells. MnSOD reduces bacterial adherence and inflammation and improves bacterial phagocytosis in mononuclear cells in response to hyperoxia, which should minimize the development of oxidant-induced lung injury as well as reduce nosocomial infections.

Keywords: mononuclear cells, bacteria, oxidant, superoxide dismutase, catalase

INTRODUCTION

While treatment with oxygen is needed to treat underlying lung disorders, hyperoxia can induce acute inflammatory changes in the lung leading to the development of acute and chronic lung injury in newborn infants (i.e. bronchopulmonary dysplasia; BPD). Reactive oxygen species (ROS) such as superoxide, hydrogen peroxide and hydroxyl radicals are primarily responsible and injure the lung by overwhelming endogenous antioxidant defense mechanisms [1]. Although bacterial infection of the lung occurs more commonly in infants with underlying lung injury, it is unclear whether exposure to hyperoxia can directly increase the risk for invasive pulmonary infection. Bacterial adherence leading to colonization is the first step in the process of invasive pulmonary infection, with phagocytosis by alveolar macrophages critically important in preventing invasive pulmonary infection. Several studies have suggested that hyperoxia impairs pulmonary immunity and increases the risk of invasive pulmonary infection in newborn animal models and preterm infants (2-6). In fact, the STOP-ROP study suggested that preterm infants receiving higher inspired oxygen concentrations had an increased incidence of pneumonia and BPD, although the study was not designed to specifically examine this outcome [2]. Preterm infants appear to be at higher risk for developing severe pulmonary infections due to immaturity of the immune system, inadequate antioxidant defenses and underlying pulmonary injury. Primary or secondary pulmonary infections can complicate an already critical situation for the premature newborn, prolonging the need for oxygen and mechanical ventilation and worsening BPD [7].

While substantial evidence now exists that antioxidant enzymes (AOE) such as superoxide dismutase (SOD) reduce hyperoxic injury, there have been few studies addressing whether this strategy will prevent or ameliorate associated pulmonary infection [8,9]. In the present study, the effects of hyperoxia on two complimentary murine macrophage cell lines were examined, focusing on bacterial adherence, phagocytosis and inflammatory cytokine production (in response to injury). Next, we determined whether overexpression of MnSOD, CuZnSOD and/or catalase would ameliorate the effects of hyperoxia. Finally, important developmental differences in the response to hyperoxia were analyzed between monocytes isolated from adult and neonatal blood.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell culture, monocyte preparation , and cell viability assays

To evaluate phagocytic function and cytokine production in response to hyperoxia, two complimentary murine macrophage cell lines (RAW264.7 - peritoneal; MHS - alveolar) were used. Our preliminary studies indicated that these cells were sensitive to hyperoxia (unlike U937 human macrophages) and could be transduced with recombinant adenoviral vectors containing AOE gene constructs. Cells were maintained in RPMI-1640 medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, 100 units/ml penicillin, 100 units/ml streptomycin (Gibco BRL, Rockville, MD) at 37 °C in 5% CO2/95% room air. Hyperoxic conditions were generated in sealed humidified chambers flushed with 5% CO2/95% O2.

Monocytes were isolated from umbilical cord blood (from 3 healthy full-term infants) or normal human peripheral blood (4 healthy volunteers) using Ficoll-Paque PLUS™ (Amersham Bioscience, Piscataway, NJ) following the manufacturer’s instructions. Membrane permeability was determined by exclusion of Trypan blue dye and cells were counted using a hemocytometer (to ensure equal plating) at baseline and again after a 24h exposure to hyperoxia.

Bacterial adherence assay

A non-mucoid laboratory strain of PA (PAO-1) was grown in tryptic soy broth (TBS). Bacterial adherence was assessed using a modified radiolabeled adherence assay (RAA) as described previously using metabolically labeled PAO-1 with [35S] methionine [9]. Briefly, RAW264.7 and MHS cells were seeded onto 12 well dishes at a density of 5.5 × 104/cm2 and allowed to adhere overnight. Cells were then exposed to 95% O2 or RA at 37°C for 24 h. Radiolabeled bacteria (108) were then added onto the cell layer and incubated for 1 h. Cells were washed with PBS to remove unattached bacteria. Cells were lysed with 1N NaOH and lysates counted in a liquid scintillation counter.

Recombinant adenovirus (rAd) mediated overexpression of antioxidant enzymes

Recombinant adenovirus (rAd) was used for overexpression of MnSOD, CuZnSOD and catalase. Viral transduction was performed with replication deficient adenovirus including rAdCMV-MnSOD,rAdCMVCuZnSOD, rAdCMV-catalase (rAd.CAT) or a rAd containing LacZ (rAd.CMVntLacZ) grown at the Gene Transfer Vector Core in the University of Iowa as previously described [10]. RAW264.7 cells were seeded and transduced with the appropriate viral constructs at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 25-75 viral particles per cell in complete media. This dosage range had previously been shown to have minimal toxicity and optimally increase AOE activity 2-3 fold in lung epithelial cells [10]. Cells were washed and replenished with fresh media after 17 h. Cells were then harvested and seeded at the density of 2.5 × 105 cells per 35 mm dish and allowed to adhere overnight.

SOD activity after transduction was assessed using two methods. First, 70 μg of crude cell lysate were separated on a 15% non-denaturing polyacrylamide gel. Bands of SOD activity were visualized as described [10]. Briefly, the gels were treated with 2.45mM nitroblue tetrazolium (NBT)/0.028mM riboflavin solution for 3 minutes followed by immersion in 16mM TEMED solution for 1 minute. Then the gels were exposed to fluorescent light until achromatic bands of SOD were revealed. MnSOD and CuZnSOD activities were measured enzymatically with the inhibition of cytochrome C-xanthine-xanthine oxidase technique at OD 550nm [11,12]. Since CuZnSOD is susceptible to inhibition by cyanide, addition or withdrawal of KCN allows differentiation of MnSOD activity from CuZnSOD [13]. A unit of SOD activity was defined as the amount of SOD required to inhibit the reduction of cytochrome c at 25°C, pH 7.8 by 50%. Catalase activity was assayed spectrophotometrically following the disappearance of hydrogen peroxide at 240nm [14]. One unit of CAT activity was defined as the amount of CAT required to decompose 1 μmol of hydrogen peroxide in 1 min at 25°C and pH 7.0.

In situ phagocytosis assay

Bacterial phagocytosis was determined by the in situ phagocytosis assay. After hyperoxic or room air exposure, 1×108 of PA was added to the cells (RAW264.7, monocytes). After 1 h, 80μg/ml of gentamycin (Abbott Labs, Chicago, IL) was added for 2 h to eradicate external bacteria (internalized bacteria remain intact). Cell culture supernatant was collected and plated onto TSB bacterial agar plates to confirm that no external bacteria survived gentamycin treatment (data not shown). Cells were washed with PBS twice and 10mM EDTA/PBS. Bacteria were released from the cells with 0.25% Triton X-100, and standard colony counts performed on TSB agar plates to quantify internalized bacteria.

MIP1-α expression

RAW264.7 cells were exposed to RA or 95% O2 for 24 h. The cell culture supernatants were collected and particulate removed by centrifugation. Macrophage inflammatory protein (MIP) 1-α expression (an IL-8 homolog expressed in murine cells) was assayed colorimetrically with an ELISA Kit (R&D systems, Minneapolis, MN) at an optical density of 450 nm. Samples were diluted to ensure that the readings were within the linear range of the assay.

Statistical Analyses

Differences in experimental groups over time were compared using analysis of variance (ANOVA) and Student’s t-tests (both paired and unpaired). P-values of <0.05 were accepted as statistically significant. Results are reported as mean ± standard deviation.

RESULTS

Hyperoxia reduces phagocytosis of bacteria

A 24h exposure to hyperoxia inhibited cell growth, but did not affect cell viability (>98% of all cells were still viable; appropriate corrections for live cells were made for all assays). RAW264.7 cells were then examined for the effects of hyperoxia on phagocytosis of a laboratory strain of PA (PAO1) using an in situ phagocytosis assay. The internalized bacteria were released from lysed macrophages, plated on agar plates, and viable bacteria determined by standard plate counting. As shown in Figure 1, the number of bacteria internalized in RA was 49.3 bacteria/cell. However, when cells were exposed to 95% O2 for 24h, bacterial internalization was reduced to 19.5 bacteria/cell, a 60% reduction (P<0.05). No colonies were formed when counts were performed on cell culture medium post-gentamycin treatment, confirming that the isolated colonies were from internalized bacteria and not from the bacteria attached to the cell surface. Using the radiolabel assay, the total number of bacteria (both internal and external) associated with macrophages was measured following cell lysis. As illustrated in Fig 1B, the total number of PA associated with RAW264.7 cells increased approximately 6 fold from 43.1dpm/102cell in RA to 255.8 dpm/102cells in hyperoxia (P<0.0001). MHS cells showed similar results with bacterial adherence increasing by 5 fold in response to hyperoxia (data not shown). These data demonstrate that hyperoxia causes increased bacterial adherence while reducing phagocytosis in macrophages.

Figure 1.

A. Hyperoxia inhibits phagocytosis in mononuclear cells. RAW264.7 cells were exposed to either RA or 95% O2 for 24 h and then PAO-1 added. Bacteria were dispersed from cells, seeded onto agar and colonies counted. Data are presented as an average of 4 independent experiments each performed in duplicate. *P<0.05 relative to RA controls.

B. Hyperoxia induces bacterial adherence in RAW264.7 cells. RAW264.7 cells were exposed to either RA or 95% O2 for 24 h, radiolabeled PAO-1 then added and adherence of PA measured. The number of PA (dpm) were normalized to cell number and data presented as an average of 6 independent experiment. *P<0.0001

Overexpression of AOE with rAd

Prolonged exposure to hyperoxia results in the formation of ROS, particularly superoxide and H2O2. To assess the roles of ROS, AOE were overexpressed in RAW267.4 cells using rAd. Enzymatic activity was determined biochemically (Table 1) and by activity gel assays (Figure 2). Endogenous CuZnSOD levels were 8-16 fold higher than MnSOD, LacZ or mock control cells (Table 1). When separated in non-denaturing conditions, the human and mouse isoforms of SOD migrate differently. While the endogenous MnSOD was below the level of detection in control cells (lane 1, Figure 2) a clear induction was seen when cells were tranduced with the rAd encoding the human MnSOD (hMnSOD, lane 3), corresponding to an increase of 142% (Table 1). Endogenous mouse CuZnSOD (mCuZnSOD) and exogenous human CuZnSOD (hCuZnSOD) were readily detectable in the activity gel (lane 2, Figure 2). While rAd.CuZnSOD transduction only increased CuZnSOD activity by 23%, catalase activity was increased by 52% (Table 1). Transgene expression was confirmed on duplicate cultures by measuring enzymatic activity prior to performance of the assays.

Table 1.

Antioxidant Activity in RAW264.7 Cells.RAW264.7 cells were transduced with rAd encoding either β-gal, CuZnSOD, MnSOD or catalase. At 48 h post-transduction cells were harvested and enzymatic activity was determined and normalized to protein concentration. Abbreviations: ND, not determined

| CuZnSOD Activity | MnSOD Activity | Catalase Activity | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gene transduced | (U/mg) | (U/mg) | (U/mg) |

| Mock control | 3.69 | 0.23 | ND |

| LacZ | 3.58 | 0.45 | 8.6 |

| CuZnSOD | 4.41 | 0.52 | ND |

| MnSOD | 4.00 | 1.09 | ND |

| Catalase | ND | ND | 13.1 |

Figure 2. Transduced SOD expression in RAW264.7 cells.

Cells were transduced with rAd encoding either β-gal the human CuZnSOD (hCuZnSOD) or human MnSOD (hMnSOD). Cells were lysed 48 h post-tranduction and lysates (70 μg) were separated on a 15% acrylamide non-denaturing gel and SOD visualized by gel zymography. Bands corresponding to the human and mouse isoforms are indicated on the right. Note: the endogenous MnSOD is below the detectable limits of the assay.

The effects of hyperoxia and overexpression of AOE on bacterial phagocytosis and adherence

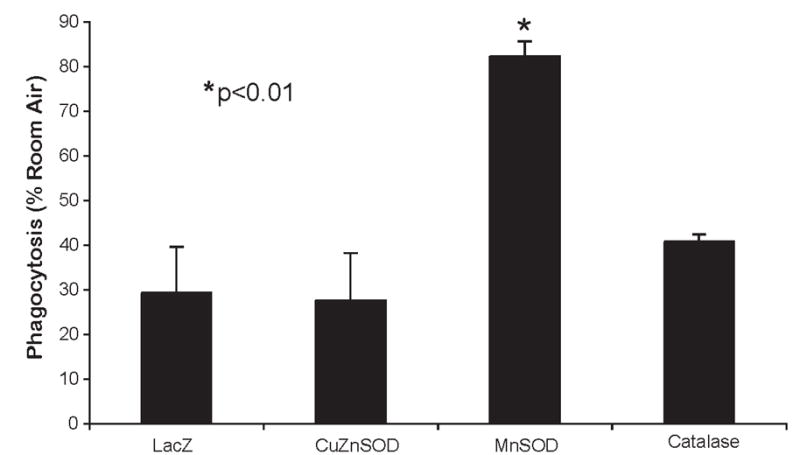

When phagocytosis of PA was determined in response to hyperoxia and AOE overexpression, distinct differences were found. While the number of internalized bacteria dropped in LacZ control cells exposed to hyperoxia to 30.9% of RA controls (P<0.01), values reached 85.2% of RA controls in cells when MnSOD was overexpressed (P<0.01). No statistically significant differences were seen in cells overexpressing CuZnSOD or catalase (Figure 3). Since MnSOD improved bacterial internalization, one would predict that the number of external bacteria would decrease in cells overexpressing MnSOD. As shown in Figure 4, overexpression of MnSOD or catalase reduced the total number of bacteria associated with the hyperoxia-exposed cells compared to LacZ controls (P<0.01). No changes were evident in the corresponding RA controls (Figure 4).

Figure 3. Overexpressing MnSOD reduces hyperoxia-induced inhibition of phagocytosis.

Cells were transduced with LacZ or MnSOD and then exposed to either RA or 95% O2 for 24 h and the number of bacteria internalized was determined by gentamycin exclusion. Values represent % phagocytosed bacteria relative to RA controls. Values represent at least 2 independent experiments performed in triplicate. *P<0.001

Figure 4. MnSOD or catalase reduces hyperoxia-induced bacterial adherence.

Cells were transduced with LacZ, MnSOD, or catalase and then exposed to either RA or 95%O2 for 24 h. Solid bars represent RA and open bars represent 95% O2 exposure. The number of PA (dpm) were normalized to live cell number and data presented as an average of 6 independent experiment. #P<0.001 and *P<0.01 relative to RA controls.

Overexpression of MnSOD decreases hyperoxia-induced MIP-1α expression

IL-8 is an important pro-inflammatory cytokine associated with lung inflammation and infection. A previous study demonstrated that MnSOD ameliorates the induction of IL-8 in epithelial cells in response to hyperoxia and PA in human lung epithelial cells [9]. To determine if MnSOD would have a similar effect in macrophages, we examined the expression of the mouse homolog MIP-1α . MIP-1α was originally identified as a product of endotoxin stimulated RAW264.7 macrophages [14, 15]. It has been shown that MIP-1α contributes to lung leukocyte accumulation and acute lung injury in various animal models [16, 17]. As shown in Figure 5, MIP-1α was increased by 40% following hyperoxic exposure (P<0.05). In contrast, cells overexpressing MnSOD had no induction of MIP-1α production in response to hyperoxia and levels were comparable to RA controls. Overexpression of other AOE (e.g. CuZnSOD or catalase) did not reduce the production of MIP-1α with similar values seen in LacZ controls. While all rAd transduced cells had reduced production of MIP-1α compared to mock transduced cells, this was largely due to the variability of expression in the mock-transduced cells (data not shown).

Figure 5. Hyperoxia induces MIP-1α production.

RAW264.7 cells were exposed to RA or 95 O2 for 24 h and MIP-1α production determined by ELISA. Solid bars represent RA and open bars represent hyperoxia. Data are presented as an average of 4 independent experiment. *P<0.05

Developmental differences

To determine if these observations could be extended to primary cells and to examine specific developmental differences, monocytes were isolated from cord blood of healthy newborn infants and compared to those from the peripheral blood of healthy adult volunteers. Hyperoxia reduced bacterial phagocytosis by 25% in monocytes isolated from cord blood (P<0.01). In sharp contrast, phagocytosis was reduced by 92% in adult peripheral monocytes exposed to hyperoxia (P<0.0001) (Figure 6). This demonstrates that adult monocytes are more impaired in response to the effects of hyperoxia.

Figure 6. Developmental differences between adult and neonatal blood monocytes.

Monocytes were isolated from cord blood or adult peripheral blood. Cells were then exposed to RA or 95 O2 for 24 h, PA added for 1h and engulfment determined by the in situ phagocytosis assay. Values represent % phagocytosed bacteria relative to RA controls. Neonatal monocytes were collected from the cord blood of 3 healthy newborns and adult peripheral blood specimens were collected from 4 healthy volunteers with experiments performed in triplicate. *P<0.01 and #P<0.0001 relative to RA controls.

DISCUSSION

In this study we demonstrate that macrophages exposed to hyperoxia had a significant: 1) increase in bacterial adherence; 2) reduction in bacterial phagocytosis, with monocytes isolated from adults significantly more impaired than those isolated from newborns; and 3) increase in MIP 1-α production. While all the AOE tested reduced bacterial adherence, only overexpression of MnSOD significantly ameliorated the effects of hyperoxia on all three of these important outcomes measures.

Exposure to prolonged hyperoxia is well recognized to be associated with the generation of excessive ROS. ROS can cause oxidation and inactivation of a variety of macromolecules in the lung including proteins, lipids and DNA [19-20]. Several studies of cells in culture have shown that cells are injured by the detrimental effects of hyperoxia [21-26]. In addition, animal models and human trials have demonstrated that exposure to prolonged hyperoxia is associated with the development of acute lung injury and the progression to chronic lung disease [1]. ROS can injure the lung by overwhelming antioxidant defenses, damaging multiple cell types, and causing the release of inflammatory mediators (with recruitment and activation of neutrophils which can amplify the response) [27]. Premature infants exposed to higher concentrations of oxygen for prolonged periods of time have been found to have a significantly increased risk for invasive pulmonary infection and worsening BPD compared to infants exposed to lower concentrations of oxygen, presumably secondary to an exacerbation of lung injury and impaired bacterial clearance [2].

Several studies have demonstrated that ROS (e.g. H2O2) can impair polymerization of actin and the process of phagocytosis. If H2O2 directly contributed to the impairment observed here, then overexpression of catalase should have been effective in reversing the effects of hyperoxia. While catalase moderated the effect of hyperoxia on adherence, it had no effect on phagocytosis. Since MnSOD overexpression was effective, it is possible that this process is mitochondrial driven. There are two possible mechanisms for this impairment. First, superoxide inhibits mitochondrial aconitase activity resulting in a reduction of ATP production [28]. Since actin depolymerization is ATP dependent, this could impair actin dynamics and protection of the mitochondria with MnSOD (with improved ATP production) could ameliorate this effect. Alternatively, superoxide or mitochondrial stress may function as a second messenger and the effects seen here could represent downstream events. While this study does not clearly differentiate these possibilities, a recent study by Kamata and colleagues supports the notion of mitochondrial-generated superoxide as a messenger molecule [29]. In addition, Gillespie and coworkers have demonstrated that oxidation of mitochondrial DNA can function as an oxidant stress sensor [30].

Bacterial colonization and subsequent invasive pulmonary infection is dependent on several factors including bacterial adherence on pulmonary epithelial cells and clearance by alveolar macrophages. We have previously demonstrated that hyperoxia increases PA adherence and IL-8 expression in lung epithelial cells and MnSOD ameliorated these processes [9]. The present data indicate that hyperoxia also increases bacterial adherence on macrophages while impairing phagocytosis and ultimately bacterial clearance. Bacterial clearance is one of the most important mechanisms to prevent invasive bacterial infection in the lung and the redox status of the lung plays a crucial role in this process [3]. Several studies have suggested that hyperoxia impairs pulmonary immunity and increases the risk of invasive pulmonary infection. Baleeiro and associates found that mice exposed to hyperoxia had increased mortality associated with gram-negative bacterial pneumonia compared to mice exposed to RA [4]. An increased bacterial burden and dissemination of the infection was also noted at the time of autopsy in the mice exposed to hyperoxia [4]. Other studies have demonstrated that an otherwise sub-lethal bacterial load of PA resulted in increased mortality in hyperoxia-exposed hamsters and a synergistic response is also supported by morphometric studies in a baboon model of BPD [5]. Crouse and colleagues demonstrated that hyperoxia caused a persistence of ureaplasma colonization, potentiates the inflammatory response and increases mortality associated with an otherwise benign infection [6]. Furthermore, O’Reilly and colleagues demonstrated that hyperoxia-exposed macrophages had impaired phagocytic function and bacterial killing of Klebsiella pneumoniae compared to normoxic controls. They concluded that oxidative stress impairs macrophage antibacterial function through effects on actin. [24]. Although the methods used in the present study did not permit us to examine bacterial killing, we have previously demonstrated that hyperoxia impairs bacterial killing in human monocytes [31]. While the addition of CuZnSOD protein actually potentiated bacterial killing, catalase interfered with killing suggesting that the increased generation of H2O2 followed SOD administration was important in the process. All of these studies reinforce the concept that hyperoxia increases bacterial colonization while impairing bacterial clearance. Treatment with antioxidants could potentially reduce lung injury and improve bacterial clearance, therefore minimizing the risk of subsequent bacterial infection.

IL-8 is a potent neutrophil chemoattractant released by multiple cell types in the lung in response to cell injury [32]. Increased IL-8 production has been associated with the development of BPD in newborn infants and increased morbidity and mortality in adults with acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) [33, 34]. We chose to analyze the mouse homolog to IL-8 (MIP-1α) in murine macrophages. Although hyperoxia significantly increased MIP-1α production, overexpression of MnSOD eliminated the upregulation of MIP-1α (suggesting less cell injury and associated inflammatory cytokine release). This should be associated with a significant blunting of the inflammatory response. This is consistent with other animal models demonstrating that inhibition of cytokines with AOE reduced inflammation and subsequent lung injury in response to prolonged hyperoxia [35, 36]. In contrast to MnSOD, CuZnSOD failed to reduce the production of MIP1-α induced by exposure to hyperoxia. We had previously demonstrated in cultured lung epithelial cells that a 2-3 fold increase in CuZnSOD activity was necessary to optimally ameliorate hyperoxic damage [10]. An MOI of 25-75 particles per cell was used for those transduction experiments, similar to what was used in the present studies. However, despite significantly increasing the MOI, CuZnSOD activity was not substantially affected. It is possible that the limited increase in exogenous CuZnSOD activity (20-30%) was insufficient to reduce the production of MIP-1α and reduce impairments in bacterial phagocytosis. Further increasing the MOI could be associated with significant cell injury from toxic effects of the virus. Although endogenous MnSOD activity was 90% lower than CuZnSOD, a 2 fold induction did result in reduced production of MIP-1α in response to hyperoxia.

It was interesting that mononuclear cells from neonatal cord blood were much more resistant to the toxic effects of hyperoxia compared to normal adult cells. Maturational differences are also apparent in rodent models with neonates being more resistant than adults. Gerik and associates demonstrated that expression of certain neutrophil adhesion molecules (L-selectin) were significantly reduced in neonatal cells in response to hyperoxia compared to adult cells [37]. Activation of NF-κB and JNK is inherently different in neonatal and adult mice [38]. The differences in the transcriptional response to hyperoxia and downstream gene expression compared to adult cells may explain in part why newborn infants are more tolerant of prolonged hyperoxia (with delayed evidence of oxygen toxicity) compared to adults.

In summary, overexpression of MnSOD was associated with reductions of bacterial adherence, improved bacterial phagocytosis, and reduced inflammation in mononuclear cells in response to hyperoxia. The beneficial effects of MnSOD were similar to those previously found in lung epithelial cells. Since CuZnSOD and catalase were not as efficacious, it is possible that protection of the mitochondria is critically important in the process of bacterial clearance by activated alveolar macrophages. This suggests that exogenous SOD may not only reduce acute and chronic lung injury in response to hyperoxia, but also prevent subsequent invasive pulmonary infection. This has important implications in the development of antioxidant supplementation to prevent lung injury and nosocomial infection in critically ill patients.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank S.H. Harkness, E.M. Gurzenda and C Hall for their technical assistance. This work was supported in part by grants from the National Institutes of Health (HL-64158-01A1), Phillip Morris USA and Phillip Morris International.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errorsmaybe discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Davis JM, Rosenfeld W. Chronic Lung Disease. In: Avery G, Fletcher M, MacDonald M, editors. Neonatology. Lipincott, Williams & Wilkins:; Philadelphia: 1999. pp. 509–532. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stop ROP Multicenter Study Group. Supplemental Therapeutic Oxygen for Prethreshold Retinopathy Of Prematurity (STOP-ROP), a randomized, controlled trial.I: primary outcomes. Pediatrics. 2000;105:295–310. doi: 10.1542/peds.105.2.295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Suntres ZE, Omri A, Shek PN. Pseudomonas aeruginosa-induced lung injury: role of oxidative stress. Microb Pathog. 2002;32:27–34. doi: 10.1006/mpat.2001.0475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baleeiro CE, Wilcoxen SE, Morris SB, Standiford TJ, Paine R., 3rd Sublethal hyperoxia impairs pulmonary innate immunity. J Immunol. 2003;171:955–963. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.2.955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Coalson JJ, King RJ, Winter VT, Prihoda TJ, Anzueto AR, Peters JI, Johanson WG., Jr O2- and pneumonia-induced lung injury. I. Pathological and morphometric studies. J Appl Physiol. 1989;67:346–356. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1989.67.1.346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Crouse DT, Cassell GH, Waites KB, Foster JM, Cassady G. Hyperoxia potentiates Ureaplasma urealyticum pneumonia in newborn mice. Infect Immun. 1990;58:3487–3493. doi: 10.1128/iai.58.11.3487-3493.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gonzalez A, Sosenko IR, Chandar J, Hummler H, Claure N, Bancalari E. Influence of infection on patent ductus arteriosus and chronic lung disease in premature infants weighing 1000 grams or less. J Pediatr. 1996;128:470–478. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(96)70356-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Davis JM, Parad RB, Michele T, Allred E, Price A, Rosenfeld W. Pulmonary outcome at 1 year corrected age in premature infants treated at birth with recombinant human CuZn superoxide dismutase. Pediatrics. 2003;111:469–476. doi: 10.1542/peds.111.3.469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Arita Y, Joseph A, Koo HC, Li Y, Palaia TA, Davis JM, Kazzaz JA. Superoxide dismutase moderates basal and induced bacterial adherence and interleukin-8 expression in airway epithelial cells. Am J Physiol: Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2004;287:L1199–1206. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00457.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Koo HC, Davis JM, Li Y, Hatzis D, Opsimos H, Pollack S, Strayer MS, Ballard PL, Kazzaz JA. Effects of transgene expression of superoxide dismutase and glutathione peroxidase on pulmonary epithelial cell growth in hyperoxia. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2005;288:L718–726. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00456.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Beauchamp C, Fridovich I. Superoxide dismutase: improved assays and an assay applicable to acrylamide gels. Anal Biochem. 1971;44:276–287. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(71)90370-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Crapo JD, McCord JM, Fridovich I. Preparation and assay of superoxide dismutases. Methods Enzymol. 1978;53:382–393. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(78)53044-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ilizarov AM, Koo HC, Kazzaz JA, Mantell LL, Li Y, Bhapat R, Pollack S, Horowitz S, Davis JM. Overexpression of manganese superoxide dismutase protects lung epithelial cells against oxidant injury. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2001;24:436–441. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb.24.4.4240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Aebi H. Catalase in vitro. Methods Enzymol. 1984;105:121–126. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(84)05016-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Davatelis G, Tekamp-Olson P, Wolpe SD, Hermsen K, Luedke C, Gallegos C, Coit D, Merryweather J, Cerami A. Cloning and characterization of a cDNA for murine macrophage inflammatory protein (MIP), a novel monokine with inflammatory and chemokinetic properties. J Exp Med. 1988;167:1939–1944. doi: 10.1084/jem.167.6.1939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wolpe SD, Davatelis G, Sherry B, Beutler B, Hesse DG, Nguyen HT, Moldawer LL, Nathan CF, Lowry SF, Cerami A. Macrophages secrete a novel heparin-binding protein with inflammatory and neutrophil chemokinetic properties. J Exp Med. 1988;167:570–581. doi: 10.1084/jem.167.2.570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Standiford TJ, Kunkel SL, Lukacs NW, Greenberger MJ, Danforth JM, Kunkel RG, Strieter RM. Macrophage inflammatory protein-1 alpha mediates lung leukocyte recruitment, lung capillary leak, and early mortality in murine endotoxemia. J Immunol. 1995;155:1515–1524. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shanley TP, Schmal H, Friedl HP, Jones ML, Ward PA. Role of macrophage inflammatory protein-1 alpha (MIP-1 alpha) in acute lung injury in rats. J Immunol. 1995;154:4793–4802. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schoonen WG, Wanamarta AH, Van der Klei-Van Moorsel JM, Jakobs C, Joenje H. Respiratory failure and stimulation of glycolysis in Chinese hamster ovary cells exposed to normobaric hyperoxia. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:1118–1124. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sullivan SJ, Roberts RJ, Spitz DR. Replacement of media in cell culture alters oxygen toxicity: possible role of lipid aldehydes and glutathione transferase in oxygen toxicity. J Cell Physiol. 1991;147:427–433. doi: 10.1002/jcp.1041470307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gille JJ, Joenje H. Chromosomal instability and progressive loss of chromosomes in HeLa cells during adaptation to hyperoxic growth conditions. Mutation Research. 1989;219:225–230. doi: 10.1016/0921-8734(89)90004-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Petrache I, Choi ME, Otterbein LE, Chin BY, Mantell LL, Horowitz S, Choi AM. Mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway mediates hyperoxia-induced apoptosis in cultured macrophage cells. Am J Physiol. 1999;277:L589–595. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1999.277.3.L589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rancourt RC, Staversky RJ, Keng PC, O’Reilly MA. Hyperoxia inhibits proliferation of Mv1Lu epithelial cells independent of TGF-beta signaling. Am J Physiol. 1999;277:L1172–1178. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1999.277.6.L1172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.O’Reilly PJ, Hickman-Davis JM, Davis IC, Matalon S. Hyperoxia impairs antibacterial function of macrophages through effects on actin. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2003;28:443–450. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2002-0153OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mantell LL, Kazzaz JA, Xu J, Palaia TA, Piedboeuf B, Hall S, Rhodes G, Niu G, Fein AM, Horowitz S. Unscheduled apoptosis during acute inflammatory lung injury. Cell Death Differen. 1997;4:604–607. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4400278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kazzaz J, Horowitz S, Li Y, Mantell L. Hyperoxia in cell culture a non-apoptotic programmed cell death. Ann NY Acad Sci. 1999;887:164–170. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1999.tb07930.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Saugstad OD. Bronchopulmonary dysplasia-oxidative stress and antioxidants. Semin Neonatol. 2003;8:39–49. doi: 10.1016/s1084-2756(02)00194-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gardner PR, Nguyen DD, White CW. Aconitase is a sensitive and critical target of oxygen poisoning in cultured mammalian cells and in rat lungs. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1994;91:12248–12252. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.25.12248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kamata H, Honda S, Maeda S, Chang L, Hirata H, Karin M. Reactive oxygen species promote TNFalpha-induced death and sustained JNK activation by inhibiting MAP kinase phosphatases. Cell. 2005;120:649–661. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.12.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ruchko M, Gorodnya O, LeDoux SP, Alexeyev MF, Al-Mehdi AB, Gillespie MN. Mitochondrial DNA damage triggers mitochondrial dysfunction and apoptosis in oxidant-challenged lung endothelial cells. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2005;288:L530–535. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00255.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Walti H, Nicolas-Robin A, Assous MV, Polla BS, Bachelet M, Davis JM. Effects of exogenous surfactant and recombinant human superoxide dismutase on oxygen dependent antimicrobial defenses. Biol Neonate. 2002;82:96–192. doi: 10.1159/000063095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kotecha S, Hodge R, Schaber JA, Miralles R, Silverman M, Grant WD. Pulmonary Ureaplasma urealyticum is associated with the development of acute lung inflammation and chronic lung disease in preterm infants. Pediatr Res. 2004;55:61–68. doi: 10.1203/01.PDR.0000100757.38675.50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Parsons PE, Eisner MD, Thompson BT, Matthay MA, Ancukiewicz M, Bernard GR, Wheeler AP. Lower tidal volume ventilation and plasma cytokine markers of inflammation in patients with acute lung injury. Crit Care Med. 2005;33:1–6. doi: 10.1097/01.ccm.0000149854.61192.dc. discussion 230-232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Munshi UK, Niu JO, Siddiq MM, Parton LA. Elevation of interleukin-8 and interleukin-6 precedes the influx of neutrophils in tracheal aspirates from preterm infants who develop bronchopulmonary dysplasia. Pediatr Pulmonol. 1997;24:331–336. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1099-0496(199711)24:5<331::aid-ppul5>3.0.co;2-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Folz RJ, Abushamaa AM, Suliman HB. Extracellular superoxide dismutase in the airways of transgenic mice reduces inflammation and attenuates lung toxicity following hyperoxia. J Clin Invest. 1999;103:1055–1066. doi: 10.1172/JCI3816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Davis JM, Rosenfeld WN, Sanders RJ, Gonenne A. Prophylactic effects of recombinant human superoxide dismutase in neonatal lung injury. J Appl Physiol. 1993;74:2234–2241. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1993.74.5.2234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gerik SM, Keeney SE, Dallas DV, Palkowetz KH, Schmalstieg FC. Neutrophil adhesion molecule expression in the developing neonatal rat exposed to hyperoxia. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2003;29:506–512. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2002-0123OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yang G, Abate A, George AG, Weng YH, Dennery PA. Maturational differences in lung NF-kappaB activation and their role in tolerance to hyperoxia. J Clin Invest. 2004;114:669–678. doi: 10.1172/JCI19300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]