Abstract

Introduction

The Ontario Stroke System was developed to enhance the quality and continuity of stroke care provided across the care continuum.

Research Objective

To identify the role evidence played in the development and implementation of the Ontario Stroke System.

Methods

This study employed a qualitative case study design. In-depth interviews were conducted with six members of the Ontario Stroke System provincial steering committee. Nine focus groups were conducted with: Regional Program Managers, Regional Education Coordinators, and seven acute care teams. To supplement these findings interviews were conducted with eight individuals knowledgeable about national and international models of integrated service delivery.

Results

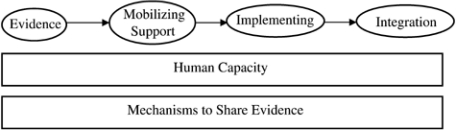

Our analyses identified six themes. The first four themes highlight the use of evidence to support the process of system development and implementation including: 1) informing system development; 2) mobilizing governmental support; 3) getting the system up and running; and 4) integrating services across the continuum of care. The final two themes describe the foundation required to support this process: 1) human capacity and 2) mechanisms to share evidence.

Conclusion

This study provides guidance to support the development and implementation of evidence-based models of integrated service delivery.

Keywords: chronic care, continuity of care, integrated care, multidisciplinary care, stroke service

Background

In many countries, the incorporation of research evidence into health care delivery is strongly encouraged. Graham [1] coined the term “knowledge to action” to describe the corresponding field of research where the central aim is to identify the best ways to incorporate research evidence into practice. This term consolidates existing terms including knowledge translation, knowledge transfer, research utilization, implementation, diffusion and many others. Graham's research identified eight key elements of the knowledge to action process: 1) identify the problem, 2) identify relevant knowledge, 3) adapt knowledge to local context, 4) assess barriers to implementation, 5) implement intervention to promote use of knowledge, 6) monitor knowledge use, 7) evaluate outcomes, and 8) sustain ongoing knowledge use [1]. These elements provide a useful framework for examining exercises to incorporate research evidence into practice.

In stroke, a problem is evident, specifically the high levels of morbidity and mortality [2]. Difficulties performing every day activities have been observed well into the first year post-stroke [3]. Coupled with the age-related nature of stroke and the aging of the population, failure to improve the delivery of stroke care could escalate this problem. Individuals who experience an acute stroke often use the full range of health care services including emergency medical services, acute care hospitals, rehabilitation, community services, and long-term care. Unfortunately, there is little continuity of care for individuals with chronic health conditions across the various health care services [4] and services received often vary considerably by region [5]. The end result of this variability and lack of continuity in services is that the health care system has difficulty providing optimal care to stroke survivors. In addition, the stroke survivor and/or family caregiver are left to coordinate these diverse and varying services adding to the stresses of recovering from stroke and providing care.

Fortunately, available evidence suggests that caring for stroke survivors in acute stroke units [6], using thrombolytic therapy (i.e. clot busting drugs like tissue plasminogen activator, tPA) [7], and providing enhanced rehabilitation care [8] can decrease stroke-related morbidity and mortality. This evidence has been translated into numerous best practice guidelines (e.g. [8–11]) and clinical care pathways [12]. Unfortunately, there are challenges associated with implementing the best evidence for stroke care. For example in a 1998 survey, 4% of acute care hospitals had stroke units and 16% were administering thrombolytic therapy [13]. Many of these challenges are associated with the need for considerable reorganization of the delivery of stroke services. Specifically in the case of thrombolytic therapy, treatment must be administered as soon as possible after the stroke occurs to be of benefit. In addition, a computed tomography (CT) scan must confirm the person has suffered an ischemic and not a hemorrhagic stroke before thrombolytic therapy can be administered. The CT scan must be reviewed by a clinician (e.g. stroke neurologist) with training in reading brain images to identify ischemic stroke. In 1998, the median wait time for a CT scan was two hours in hospitals that had a scanner and 12 hours for those who did not [13]. Furthermore, family physicians, who are not routinely trained to administer thrombolytic therapy, were the attending physicians for 78% of admitted stroke patients [13]. As a result, changes to stroke care delivery and professional development are required to implement best practice for stoke care. The solution to these problems in our region was the development of the Ontario Stroke System a model of integrated service delivery [14].

The goals of models of integrated service delivery are to enhance quality of care and quality of life, consumer satisfaction and system efficiency for patients with complex, long-term problems cutting across multiple services, providers and settings (e.g. stroke) [15]. Integration can occur at many levels including policy, finance, management, and clinical [16]. In addition, these systems may be integrated horizontally (i.e. coordination of care across similar care providers, e.g. hospital to hospital) and/or vertically (i.e. coordination of care across the continuum, e.g. hospital to home).

Research objective

To date, we do not know how the two fields, knowledge to action and models of integrated service delivery, work together to support evidence-based changes in delivery of care. The objective of the current research was to examine the role evidence played in the development and implementation of the Ontario Stroke System. This study was part of a national project examining the role of knowledge to action strategies in programs aimed at improving the delivery of stroke care in urban and rural environments.

Methodology

Design

This study used a case study approach. The Ontario Stroke System was chosen because it was viewed as a success story in obtaining government approval and funding and had made substantial progress in system implementation. The project data were collected between August 2004 and March 2005. Institutional Research Ethics Boards approved the study from an ethical perspective.

Research case: The Ontario Stroke System

The Province of Ontario's Ministry of Health and Long-term Care formally announced their support of the Ontario Stroke System in 2000 following a three-year demonstration project that tested the model of region-wide coordinated stroke care across the continuum of care in four regions. Each of the four regions pilot tested a specific aspect of the proposed model of care including a primary prevention clinic for individuals at high risk for stroke (e.g. individuals who have experienced a transient ischemic attack), secondary prevention clinic for stroke survivors, a public awareness campaign [17], and a system for routinely collecting clinical and service use data (i.e. Registry of the Canadian Stroke Network [18, 19]). The Ontario Stroke System was developed in response to the growing aging population, the research supporting the benefits of thrombolytic therapy and acute stroke units, and the existing fragmented and inconsistent care across the province and care continuum for individuals who experience a stroke and their families [13]. The purpose was to ensure that all Ontarians had access to appropriate, quality stroke care in a timely manner.

The four driving principles of the Ontario Stroke System were comprehensiveness, integration, evidence-based, and province wide [20]. It endeavored to coordinate stroke survivor care across the continuum ranging from primary prevention through to community and long-term care. The province was divided into regions containing Regional Stroke Centers, secondary prevention clinics, District Stroke Centers, community hospitals, rehabilitation facilities, community care, and long-term care facilities, where stroke care was organized and provided according to best practices (e.g. stroke units and teams, integrated care pathways). Regional Stroke Centers provided organization and structure across the continuum to the entire region. Transfer agreements enhanced coordination between elements of the system (e.g. repatriation to community hospitals, medical redirect for ambulances) and were in place or development in most regions. Work was also in progress to improve coordination between hospital, rehabilitation, long-term, and community care.

At the time of this study, each region contained a steering committee, medical director, Regional Program Manager, Regional Education Coordinator, and an acute care team. There was also a province wide steering committee consisting of representatives from the Heart and Stroke Foundation of Ontario, the Ministry of Health and Long-term Care, and regional steering committees. The composition of this group has changed over time but their responsibility has consistently been to conceptualize, obtain support for, implement, and oversee the Ontario Stroke System.

Participants

Research participants were chosen to represent diverse aspects of the Ontario Stroke System structure: 1) members of the provincial steering committee; 2) Regional Program Managers; 3) Regional Education Coordinators; and 4) members of the acute care teams including nurses, occupational therapists, physiotherapists, speech language pathologists, social workers, case managers, and dieticians. Acute care teams were selected to represent the diversity within the province of Ontario (urban, rural, teaching, community, and northern hospitals) and diversity within the system (new vs. established center). Our research focused on stroke care provided in the acute care environment by clinical teams because this was the most extensively developed aspect of the Ontario Stroke System at the time of the study. The perspectives of individuals from non-acute care sector (e.g. rehabilitation facilities, home care, and long-term care), and of patients and families, were beyond the scope of this study and will be considered in future research. To supplement our study of the Ontario Stroke System, we also interviewed key individuals centrally involved in other national and international models of integrated service delivery including stroke, programs for the aged, and other clinical groups. All participants provided written informed consent. Participant characteristics are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Participant characteristics

| Characteristic | N/Mean |

|---|---|

| Steering Committee | (n=6) |

| Ministry of Health and Long-term Care | 3 |

| Heart and Stroke Foundation of Ontario | 2 |

| Clinician | 1 |

| National and International Models | (n=8) |

| Canada | 6 |

| International | 2 |

| Illness Focus of National and International Model Participants | |

| Stroke | 3 |

| Aging | 2 |

| Other | 3 |

| Focus Groups (n=9) | (n=58) |

| Regional Program Managers | 9 |

| Regional Education Coordinators | 8 |

| Clinical Team Members | 41 |

| Clinical Training of Focus Group Participants | |

| Nurses | 23 |

| Physiotherapists | 11 |

| Speech Language Pathologists | 8 |

| Occupational Therapists | 6 |

| Social Workers | 4 |

| Nurse Practitioner/Clinical Nurse Specialist | 4 |

| Other | 2 |

| Number of years in practice (mean) | 14 |

| Number of years at current institution (mean) | 8 |

Data collection

Data were collected using in-depth interviews and focus groups. In-depth interviews were conducted with members of the provincial steering committee and individuals representing other national and international models of service delivery. Focus groups were conducted with: a) Regional Program Managers; b) Regional Education Coordinators; and c) acute care teams. Interview and focus group guides were tailored to each group of participants to address their different roles within the system. Focus group participants were also asked to provide demographic and professional background information. All participants were asked to describe their role in stroke care and to identify how evidence was used and transferred within their health care system including their perception of facilitators and challenges.

Data analysis

All interviews and focus groups were audio taped, professionally transcribed, and imported into qualitative data analysis software, NVivo version 2.0. Interviews and focus groups were reviewed by two researchers who individually developed codebooks. These researchers then worked together to merge their codebooks to be used in data analysis. Open, axial, and selective coding were used to code the documents and organize the codes into categoriesand then into themes [21]. The data were examined within and across participant groups to identify themes unique to specific groups of participants and themes representative of the full sample. For example, some topics were discussed by all participants and some topics were unique to sub-sets of the sample. These similarities and differences across data sources will be highlighted in the discussion of themes.

Research findings and key themes

Themes

Each group of participants built upon and extended themes identified by other participants. Six themes emerged: 1) use of evidence to inform system development; 2) mobilizing support for the system; 3) getting the system up and running; 4) integrating services across the continuum of care; 5) human capacity; and 6) mechanisms to share evidence (see Figure 1). These themes are summarized in Table 2 and presented below, along with illustrative quotes from the interviews and focus groups. The first four themes describe how different types of evidence were used to change the delivery of stroke care. The final two themes describe elements that supported system change and the use and flow of evidence. After each quote, letters and numbers are used to identify the source with “SC” representing provincial steering committee interviews, “IM” representing individuals associated with national and international models, and “FG” representing focus groups (note: Regional Program Managers are FG—8, Regional Education Coordinators are FG—7, clinical care teams are FG—1 through 6 and 9).

Figure 1.

Overall model of describing key elements in the development and implementation of the Ontario Stroke System.

Table 2.

Summary of key themes and types of evidence

| Theme | Type of Evidence | Details |

|---|---|---|

| Use of evidence to inform system development | • Scientific | • Use existing evidence to support initial development |

| • Generation of new evidence to inform system changes | ||

| Mobilizing government support | • Scientific | • Potential economic benefits of changing stroke care delivery |

| • Demonstration projects | • Benefits demonstrated by early programs and other models of service delivery | |

| • Other models of integrated service delivery | ||

| Getting the system up and running | • Evidence-based guidelines | • Guide system implementation |

| • Demonstration projects | • Concrete examples of guideline application | |

| Integrating Services across the Continuum of Care | • Evidence-based guidelines | • Guidelines cross care continuum and health care professionals, thereby, encouraging integration at local and system levels |

| Human Capacity | • Continued professional education | • Learning stroke best-practices |

| • Evidence based guidelines | • Adequate number of health care professionals to implement guidelines | |

| • Scientific | • New crop of researchers trained within the system | |

| Mechanisms to Share Evidence | • System change | • Informal—health care professional to health care professional |

| • Formal—Regional Education Coordinators |

Definition of evidence

Prior to introducing the themes, we will summarize the many different connotations of the word “evidence” as discussed by participants. Evidence included research from the scientific literature (e.g. Cochrane reviews for stroke units and thrombolytic therapy); economic evidence of the benefits of implementing an organized approach to stroke care; best practice guidelines; and knowledge gained from demonstration projects and comparable models of integrated service delivery. As each theme is presented, we indicate the specific type(s) of evidence referred to in the theme.

Theme 1: use of evidence to inform system development

All the participants felt that scientific evidence played an important role in informing the development of models of integrated service delivery but members of the provincial steering committee and representatives of national and international models discussed this in more detail. Participants highlighted the importance of using good quality evidence from two main sources: 1) existing evidence (e.g. literature) and 2) new evidence (e.g. new data collected by the stroke registry). For example, one national model key informant discussed the role existing scientific literature played in the development of their system:

. . . would scour the literature, would do the research, bring together the evidence, develop the standards and then through that … we would deliver upon that standard in the communities, so basically what we end up with was a [illness] related integrated service delivery network IM—1.

New evidence was also an important issue. Specifically, participants discussed the need to obtain new data to monitor system implementation, evaluate its impact, and inform best practices and system change. For example, one steering committee interviewee discussed the role of collecting new data to monitor the success of the program:

But at the front end, what we should have done was pay more attention to linking up with a third party and creating that base line, this is when you started, really promote the notion of a very long-term study, you know 5, 7, 10 years. Some organization like [organization] to track this and answer the very fundamental question: so what did I get for my money 10 years from now? SC-04

Overall, existing and new scientific evidence made substantial contributions to development of models of service delivery. The availability of good quality evidence helped determine the characteristics and components of the models. In addition, the need to collect new evidence to evaluate implementation and effectiveness and to inform new best practices and changes to service provision were also identified as important.

Theme 2: mobilizing government support

Once the scientific evidence supported a need for improvements in stroke care delivery, the next phase in implementing these changes was to get financial support by mobilizing the appropriate funding body (e.g. the Ministry of Health in the province of Ontario). The provincial steering committee and national and international model interviewees contributed to this theme. Various kinds of evidence were used to obtain the support of funding bodies. The first type of evidence was economic. In Ontario, the steering committee members worked with an expert in economic modelling to highlight the potential cost-saving benefits of implementing the system:

. . . we went through that whole process of developing the policy statement and the key to that policy statement was not only did we bring all the evidence to bear on this document, we also had a few kind of carrots with very strong evidence from an economic standpoint that if we developed an organized stroke care that involved increasing the number of patients getting tPA [thrombolytic therapy] and increasing the number of stroke units that would care for patients it would have a huge economic impact. SC-1

Demonstration projects, as described previously, were the provinces' first attempt at implementing aspects of the proposed system of care. One provincial steering committee participant highlighted the important role the demonstration projects played in obtaining government support for the system:

. . . the demonstration project turned out to be a critically successful factor, in that the [government] people were so into this [organized care] SC-06

In addition, evidence derived from other models of integrated service delivery, both successful and unsuccessful, was used. In this example, a quote from a national model interviewee explained how the government had experience with another program that didn't work and that they were interested in a new approach:

. . . the solution experimented so far and I have in mind the [other model of integrated service delivery] project in [city], was not satisfying the policy makers at the [government] because … So they were not satisfied by that experiment and they were very interested in the new model IM-6

In different regions and countries, evidence made an important contribution to obtaining financial or other forms of governmental support. The economic evidence demonstrated how the system could be cost effective. Demonstration projects and other models, successful and unsuccessful, demonstrated that other programs had been tested and that there was the opportunity to improve on these earlier programs.

Theme 3: getting the system up and running

Once governmental support for the model of service delivery was obtained, the next challenge was to implement the system across the province and across the care continuum. An important aspect of the Ontario Stroke System was the development of evidence-based guidelines to clearly articulate and operationalize the system's objectives. System implementation focused on adoption and use of the guidelines. Focus group participants made a large contribution to this theme. They discussed the benefits of having guidelines to provide clear direction for system implementation:

. . . the stroke strategy is very helpful in that it breaks it down into very clear guidelines… for all the different levels of care, so it has, clear direction for emergency care, acute care, rehab long-term care, community reintegration. FG-1

In addition to the guidelines, the demonstration projects were an important source of initial learning as they served as examples of actual applications of the guidelines. One focus group participant highlighted the benefits of learning from those early experiences:

Well I think the demonstration phase was probably really important in terms of some initial learning. FG-8

Implementation of the Ontario Stroke System was well underway at the time of this study. Best practice guidelines and demonstration projects were key sources of evidence used during system implementation. Best practice guidelines provided a template for achieving system changes and the demonstration projects provided concrete examples of how aspects of the guidelines could be implemented.

Theme 4: integrating services across the continuum of care

Facilitating integration of care across health care professionals, regionalized health care services, and the province was an important aspect of system implementation. The evidence-based practice guidelines addressed the entire care continuum and all members of the health care team. Therefore, they supported integration within and between health care services. One aspect of integration that seemed to be functioning well at the acute care team level was that health care professionals from different disciplines obtained an understanding of each other's roles with respect to patient care. As a result, they felt that the quality of patient care improved. One focus group participant discussed the resulting collaboration between health professionals and the positive effect on patient care in the acute care environment:

. . . there's also a very strong focus on interdisciplinary approaches so no-one really works in isolation, we're all collaborating, working towards the same goals for our patients and I think that really improves our care, makes it a lot more effective that we understand what our roles are and how we work together towards best practice. FG—4

The evidence-based practice guidelines included the entire continuum of care. As a result, there was an increased impetus to improve the coordination of care across services. One focus group participant highlighted how this approach has the potential to improve stroke survivors' journeys through the system:

a big word that I would use also would be coordinated best practice system… coordinated and best practices across the stroke survivor's whole journey through the health care system from their GP through to the emergency, 911 driver into the emerg, the hospital out to rehab, and home care and then back to their GP [general practitioner], the big circle. FG—4

Evidence-based practice guidelines that are directed at all members of the health care team and health care services across the care continuum have the potential to improve the well-being of stroke survivors and their family caregivers. The acute care teams fostered integration of patient care at the acute care level, but at the time of this study an integrated system was not yet in place to provide patients and their family with a seamless transition across the care continuum.

Theme 5: human capacity

Themes 5 and 6 identify aspects of the Ontario Stroke System that were important for supporting health system development and evidence implementation described by the first four themes. Human capacity concerned the availability of individuals to support the system of care. Correspondingly, the unavailability of these individuals made implementation more challenging. All study participants contributed to this theme. Unique aspects were added by the focus groups including the availability of funding to support academic training, the influence of human capacity on their ability to adopt best practice guidelines, and the variability in human capacity across the care continuum.

Individuals at all levels of the Ontario Stroke System were identified as important for the success of the system. Continuing education opportunities were viewed as important preparation for health professionals to adopt best practice guidelines. One focus group participant discussed the importance of the stroke system having funding available to support conference attendance and this was most significant for participants living in rural and remote communities:

I think probably the biggest thing is that we have more education funds and that we're able to get to these conferences that are often held in larger cities and it takes a lot of cash to get from here to there. FG—2

Attending conferences gave clinical team members the opportunity to keep up to date with new research findings. Beyond the need for better-informed people, was the need for an adequate number of well-trained health professionals in each aspect of the care continuum. Although there were challenges in implementing the practice guidelines in relatively well staffed acute care environments; the lack of resources in the community has limited the ability to fully implement community-based practice guidelines. One focus group participant highlighted the limitations in the availability of community-based care providers:

. . . there are elements of the continuum that are very weak and I'd say in our region home care is struggling so if you have stroke patients who go out, we have months and months of waiting time for personal support workers or big delays in getting therapy FG-4.

There was also discussion of the development of new researchers to generate new evidence that would contribute to the future of the system. For example, a national model key informant highlighted the need for academic training within the system:

I hope that the new generation of researchers will have joined the team and will explore new areas and improve the mechanisms and tools we've designed so far. IM—6.

Human capacity, or the availability of an adequate number of trained individuals to support the system, was an important issue. These ranged from researchers who could generate evidence to inform system change to adequate numbers of appropriately trained clinicians to implement best practices at the patient level. The need for appropriate human capacity in the clinical care teams may not have been adequately addressed by system changes to date. Finally, funding was viewed as important as it supported attendance at professional training events (e.g. conferences).

Theme 6: mechanisms to share evidence

The final theme supporting system development and implementation concerns the sharing of evidence and best practices guidelines across and within the system. Primarily focus group participants discussed this theme. There are a number of different mechanisms, formal and informal, used to move evidence through the Ontario Stroke System including, workshops and conferences, journals and print material, hospital rounds and/or in-services, the use of technology (e.g. web-sites, email), and from key individuals including Regional Education Coordinators. A considerable amount of information sharing occurred in informal one-on-one situations as this focus group participant illustrates:

I'm talking to a physio about a particular patient—they ask something about my role and what I'm doing with a patient and I'll refer to the Stroke Strategy in that context … Or if you show up and say “Hi, I'm with the stroke team” sometimes people will even ask you at that point “so what are you doing here?” and that's an opportunity for educating people. FG—9

In this situation, a member of the stroke team used clinical opportunities to share information about the Ontario Stroke System with colleagues. In addition to these informal exchanges of information, the Ontario Stroke System developed the Regional Education Coordinator position to support the formal exchange of best practice guidelines and new research findings across the care continuum in their regions. Education coordinators were responsible for providing and/or organizing formal learning opportunities. For example, this focus group participant discussed “lunch and learn” sessions as a method to bring clinical team members up to date on practice changes:

. . . to do a lunch and learn with the staff to show them and provide them with a little bit of background information and what we've done with the Pathways, where we'd like to go and then to kind of really put it on the table for discussion with them. FG—1

Information sharing through both formal and informal channels supported system implementation and dissemination of best practices and new evidence. Regional Education Coordinators played an essential role in this process.

Discussion

Evidence played a central role in the development and implementation of systems of integrated service delivery. Evidence came in different forms depending upon its intended use. Scientific evidence greatly influenced the development of the system, including identifying the key components of the system of care. Economic evidence on the financial benefits of the program and evidence from other programs were essential in persuading the government to support proposed models of integrated service delivery. Scientific evidence needed to be translated into evidence-based guidelines to enable implementation. Guidelines crossed the care continuum which encouraged the integration of services. Aspects of the system, human capacity and mechanisms of sharing evidence, were key in supporting the movement and use of evidence within the system.

Returning to Graham's eight elements of the knowledge to action process reveals how these eight elements are applied in the development and implementation of a model of integrated service delivery. Thus, these two fields of research are closely intertwined. Specifically, existing literature highlighted the problems with stroke care and, therefore, identified a need for changes to stroke care delivery. Existing evidence was obtained from the scientific literature, economic evidence, and lessons learned from demonstration projects and other models of integrated service delivery. Best practice guidelines were used to adopt the evidence to be used in the province of Ontario. Barriers to implementation were identified as a result of this research. Specifically, the availability of an adequate number of appropriately trained health care professionals served as a key barrier to implementing the best practice guidelines across the care continuum. This research also reveals how implementation of the evidence is a long-term and ongoing process. The Ontario Stroke System was implementing the system in phases starting with acute care. In addition, strategies must be put in place to support the integration of new evidence once it becomes available. Our findings also shed light on the use of evidence within the Ontario Stroke System. Specifically, improved collaboration between health care professionals in the acute care environment was thought to be associated with better patient outcomes. Evaluation of outcomes (e.g. improvements in patient outcomes, health service utilization) was not captured in this study. Finally, the incorporation of the Regional Education Coordinator position in the Ontario Stroke System enhances the likelihood that there will be ongoing use of new knowledge within the system.

Our findings have important implications for the development of other evidence-based models of integrated service delivery. First, as highlighted earlier, it is important to recognize that evidence comes in different forms and serves various purposes during the development and implementation of a model of integrated service delivery. Evidence ranged from scientific, to economic, to other models of service delivery, to evidence-based guidelines. A second important learning, is that evidence-based practice guidelines that cross the care continuum emphasize the importance of all elements of the continuum. Third, it is important to take into consideration the variability in the training and availability of health care professionals across the care continuum with community care more commonly understaffed than acute care [22]. Additional financial resources may be needed to increase the availability of skilled health care professionals in the community. Fourth, integration and evidence transfer is enhanced through the inclusion of formal positions within the system (i.e. Regional Program Managers and Regional Education Coordinators) whose responsibilities are to implement the system across the care continuum and enhance the best-practice guidelines. Others interested in developing and implementing models of integrated service delivery may benefit from using the key findings from this study.

Future research is needed to further our understanding of the extent and benefits of integrating stroke care across the care continuum. The perspectives of patients and families were not captured in this study. Future research should explore their experiences with the system of care, especially their journey across the care continuum as this is one aspect where the Ontario Stroke System still has difficulty. In addition, evaluation research is needed to determine the improvements in stroke outcomes and service use as a result of the system of care. Finally, future research should test different mechanisms of coordinating patient care across the care continuum. This may come in the form of electronic patient records (e.g. [23]), case managers dedicated to supporting patient transitions across care environments (e.g. [24]), or self-management strategies to help patients and families to self-manage their transitions across care environments (e.g. [25]).

Study strengths

This study had a number of strengths. Participants were derived from a variety of sources to obtain a comprehensive view of the Ontario Stroke System. Key individuals from the Heart and Stroke Foundation, provincial government, and clinicians involved in the development and implementation of the system were included. In addition, focus groups were conducted with acute care teams from across the province and include teaching, non-teaching, urban, rural, and northern hospitals. They also included regions that were in the earlier and later stages of Ontario Stroke System adoption. In addition, we also supplemented our findings for the Ontario System by obtaining the perspectives of key individuals from a variety of other national and international models of integrated service delivery. This project also employed rigorous qualitative research methodology. This included using interview guides, professional transcription, codebook development and testing for inter-coder agreement, and four members of the research team reviewed the transcripts enhancing the robustness of the findings.

Study limitations

The study also had some limitations. It was conducted in the Canadian context where there is a publicly funded universal health care system available to all members of the population. Therefore, these findings are not representative of all health care systems. In Canada at the time of this study, Ontario was one of the few provinces that did not have a regional approach to health care. As a result, the efforts at improving the continuity of care across the continuum may have been more challenging in Ontario as compared to other provinces that have experience with regional approaches to health care. This study also placed a large emphasis on the acute care part of the continuum since, at the time of this study, this aspect was the most developed. Therefore, our themes may not fully reflect the role of evidence in other aspects of the care continuum (e.g. rehabilitation, long-term, and community care). Future research can focus on the use of evidence in the rehabilitation and community aspects of the Ontario Stroke System.

Conclusions

This study provides guidance in how different forms of evidence are used in the design and implementation of models of integrated service delivery. Four main stages were identified: using evidence to inform system development, mobilizing government support, implementing the system, and integrating services across the care continuum. The availability of appropriate human capacity and mechanisms to share evidence supported system development and implementation. This research has added to our understanding of how system change is accomplished and how evidence of different forms facilitates this process.

Acknowledgments

This project was supported by a research grant from the Canadian Stroke Network.

Contributor Information

Jill I. Cameron, Department of Occupational Science and Occupational Therapy, University of Toronto, Toronto Rehabilitation Institute, Canada.

Susan Rappolt, Department of Occupational Science and Occupational Therapy, University of Toronto, Toronto Rehabilitation Institute, Canada.

Mary Lewis, Heart and Stroke Foundation of Ontario, Canada.

Renee Lyons, Atlantic Health Promotion Research Center, School of Health and Human Performance, Dalhousie University, Canada.

Grace Warner, School of Occupational Therapy, Dalhousie University, Canada.

Frank Silver, Toronto Western Hospital Stroke Program, Faculty of Medicine, University of Toronto, Canada.

Reviewers

Giuseppe Micieli, Dr, Neurology and Stroke Unit, IRCCS Istituto Clinico Humanitas, Rozzano (Milano), Italy.

Mirella Minkman, RN, MSc, Senior advisor & researcher, Project leader Integrated Care. Dutch Institute for Healthcare Improvement CBO, Utrecht, The Netherlands.

Mathieu Ouimet, PhD, Assistant Professor, Department of Political Sciences, Faculty of Social Sciences, Université Laval, Québec, Canada.

References

- 1.Graham ID, Logan J, Harrison MB, Straus SE, Tetroe J, Caswell W, et al. Lost in knowledge translation: time for a map? Journal of Continuing Education in the Health Professions. 2006 Winter;26(1):13–24. doi: 10.1002/chp.47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Raina P, Dukeshire S, Lindsay J, Chambers LW. Chronic conditions and disabilities among seniors: an analysis of population-based health and activity limitation surveys. Annals of Epidemiology. 1998 Aug;8(6):402–9. doi: 10.1016/s1047-2797(98)00006-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mayo NE, Wood-Dauphinee S, Cote R, Durcan L, Carlton J. Activity, participation, and quality of life 6 months poststroke. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. 2002 Aug;83(8):1035–42. doi: 10.1053/apmr.2002.33984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bergman H, Beland F, Lebel P, Contandriopoulos AP, Tousignant P, Brunelle Y, et al. Care for Canada's frail elderly population: fragmentation or integration? Canadian Medical Association Journal. 1997 Oct 15;157(8):1116–21. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yiannakoulias N, Svenson LW, Hill MD, Schopflocher DP, James RC, Wielgosz AT, et al. Regional comparisons of inpatient and outpatient patterns of cerebrovascular disease diagnosis in the province of Alberta. Chronic Diseases in Canada. 2003 Winter;24(1):9–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stroke Unit Trialists' Collaboration. Organised inpatient (stroke unit) care for stroke. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2001; 3. Art. No.: CD000197. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD000197. Available from: http://www.mrw.interscience. wiley.com/cochrane/clsysrev/articles/CD000197/frame.html. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Wardlaw JM, del Zoppo G, Yamaguchi T, Berge E. Thrombolysis for acute ischaemic stroke. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2003; 3. Art. No.: CD000213. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD000213. Available from: http://www. mrw.interscience.wiley.com/cochrane/clsysrev/articles/CD000213/frame.html. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Duncan PW, Horner RD, Reker DM, Samsa GP, Hoenig H, Hamilton B, et al. Adherence to postacute rehabilitation guidelines is associated with functional recovery in stroke. Stroke. 2002 Jan;33(1):167–77. doi: 10.1161/hs0102.101014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.National clinical guidelines for stroke: a concise update. Clinical Medicine. 2002 May-Jun;2(3):231–3. doi: 10.7861/clinmedicine.2-3-231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bliss J. New clinical guidelines for patients with stroke. British Journal of Community Nursing. 2000 Apr;5(4):160. doi: 10.12968/bjcn.2000.5.4.7407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brown J, Bernstein M. Antithrombotic therapy for patients with stroke symptoms. Guidelines for family physicians. Canadian Family Physician. 1996 Sep;42:1724–30. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Campbell H, Hotchkiss R, Bradshaw N, Porteous M. Integrated care pathways. British Medical Journal. 1998;316(7125):133–7. doi: 10.1136/bmj.316.7125.133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tu JV, Porter J. Stroke care in Ontario: hospital survey results. Toronto: Institute for Clinical and Evaluative Sciences. 1999 [Google Scholar]

- 14.Black D, Lewis M, Monaghan B, Trypuc J. System change in healthcare: the Ontario Stroke Strategy. Hospiral Quarterly. 2003;6(4):44–7. doi: 10.12927/hcq..16610. 2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kodner DL, Spreeuwenberg C. Integrated Care:Meaning, logic, applications, and implications: a discussion paper. International Journal of Integrated Care [serial online] 2002 Nov;14:2. doi: 10.5334/ijic.67. Available from: http://www.ijic.org. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Leutz WN. Five laws for integrating medical and social services: lessons from the United States and the United Kingdom. Millbank Quarterly. 1999;77(1):77–110. iv–v. doi: 10.1111/1468-0009.00125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Silver FL, Rubini F, Black D, Hodgson CS. Advertising strategies to increase public knowledge of the warning signs of stroke. Stroke. 2003 Aug 1;34(8):1965–8. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000083175.01126.62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nadeau JO, Shi S, Fang J, Kapral MK, Richards JA, Silver FL, et al. TPA use for stroke in the Registry of the Canadian Stroke Network. The Canadian Journal of Neurological Sciences. 2005 Nov;32(4):433–9. doi: 10.1017/s0317167100004418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tu JV, Willison DJ, Silver FL, Fang J, Richards JA, Laupacis A, et al. Impracticability of informed consent in the Registry of the Canadian Stroke Network. The New England Journal of Medicine. 2004 Apr 1;350(14):1414–21. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa031697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Report of the Joint Stroke Strategy Working Group. Towards an integrated stroke strategy for Ontario. Toronto, Ontario: Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Creswell JW. Qualitative Inquirey and research design: choosing among five traditions. London: Sage Publications; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wilkins K, Park E. Home care in Canada. Health Reports. 1998 Summer;10(1):29–37. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhang J, Sun J, Yang Y, Chen X, Meng L, Lian P. Web-based electronic patient records for collaborative medical applications. Computerized Medical Imaging and Graphics. 2005 Mar;29(2–3):115–24. doi: 10.1016/j.compmedimag.2004.09.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hebert R, Durand PJ, Dubuc N, Tourigny A. PRISMA: a new model of integrated service delivery for the frail older people in Canada. International Journal of Integrated Care [serial online] 2003 Mar 18;3 doi: 10.5334/ijic.73. Available from: http://www.ijic.org. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Coleman EA, Smith JD, Frank JC, Min SJ, Parry C, Kramer AM. Preparing patients and caregivers to participate in care delivered across settings: the Care Transitions Intervention. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2004 Nov 1;52(11):1817–25. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2004.52504.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]