Abstract

Pancreatic surgeons need to be aware of, and have the expertise available to deal with, unexpected vascular anomalies encountered during pancreatic resections. We present a patient with celiac artery occlusion that was encountered unexpectedly during pancreaticoduodenectomy. As a result of this anomaly, the celiac territory is dependent on retrograde flow via collaterals from the superior mesenteric artery. We discuss the method of identifying this situation, and of revascularising the celiac trunk to prevent ischaemia of upper abdominal viscera. We highlight the implications for surgical training.

Keywords: Pancreatic resection, Celiac artery occlusion, Pancreaticoduodenectomy

Arterial anomalies in the region of pancreas and liver are common: surgeons must be aware of these variations and must have the ability to deal with unexpected vascular problems. Acquired arterial anomalies usually occur when a major feeding vessel occludes, usually due to atherovascular disease. Celiac artery occlusion is a common finding in older adults, and stenosis is present in up to 10% of patients undergoing pancreaticoduodenectomy.1 Such occlusion is generally well tolerated without any symptoms, thanks to the rich anastomotic network between the celiac and superior mesenteric arteries (SMA). This anastomotic network occurs at three sites: branches of the superior and inferior pancreaticoduodenal arteries in the head of the pancreas, branches of the dorsal pancreatic artery in the body of the pancreas, and the rarer artery of Buhler connecting the two trunks.2 The most important of these collaterals is the pancreaticoduodenal arcade, which then supplies blood to the hepatic artery via retrograde flow in the gastroduodenal artery (GDA). Disturbance of these collaterals in the setting of celiac artery occlusion can result in irretrievable ischaemic injury to upper abdominal viscera.

We describe a case of celiac artery occlusion to emphasise the importance of appreciating unexpected vascular anomalies encountered during pancreatic resections. It also highlights the need for upper gastrointestinal surgeons to possess adequate vascular surgical skills, and the implications for surgical training.

Case report

A 60-year-old ex-smoker was admitted with a 5-week history of abdominal discomfort, jaundice, nausea and weight loss. He was a non-insulin dependent diabetic, and had ischaemic heart disease since 12 years. Ultrasound examination showed dilatation of both intrahepatic and common bile ducts, and identified a hypo-echoic lesion in the head of pancreas. A contrastenhanced computerised tomogram confirmed a localised tumour suspicious of malignancy. It was deemed suitable for resection, and the patient was advised to undergo a Whipple's operation.

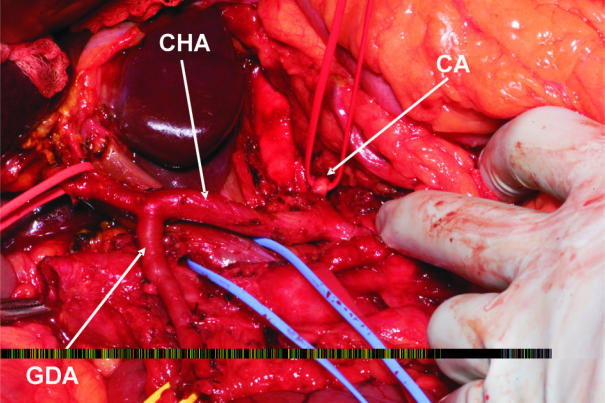

At surgery, the GDA was very prominent and measured the same size as the proper hepatic artery. On occluding the GDA, pulsations of the proper hepatic artery ceased, confirming that the GDA was the main feeding vessel to the liver. The GDA was dissected off the head of the pancreas, but the entire pancreaticoduodenal arcade could not be preserved, as this would have interfered with successful resection of the tumour. The celiac artery was occluded, but the calibre of its branches, namely the common hepatic, left gastric and splenic arteries, was normal (Fig. 1). To preserve arterial inflow to the liver, the celiac artery was divided, and its trifurcation was re-implanted into the aorta just above its normal origin. This restored normal hepatic arterial pulsations when the GDA was occluded. A standard Whipple procedure could be successfully completed.

Figure 1.

Operative photograph showing an atretic celiac artery (CA), with a normal sized common hepatic artery (CHA) that is fed by retrograde flow in an enlarged gastroduodenal artery (GDA).

The patient made a good recovery with no postoperative complications. There was no biochemical evidence of hepatic or renal ischaemia in the postoperative period, and duplex ultrasonography confirmed normal hepatic arterial pulsations. Histopathology revealed a 23-mm, moderately differentiated, ductal adenocarcinoma of the pancreas, clear of all the resection margins, but involving one of seventeen resected lymph nodes. The patient received adjuvant chemotherapy within a clinical trial, and remains well with no evidence of recurrent disease after 5 months.

Discussion

Stenosis of the celiac artery is present in up to 10% of patients undergoing pancreaticoduodenectomy, as reported in series where arteriography was routinely performed before surgery.1 Pancreaticoduodenectomy for cancers of the head of the pancreas involves division of the GDA. In the event of celiac axis occlusion, the procedure poses an ischaemic threat to the liver and the hepaticojejunal anastomosis. This problem is well recognised in the literature, and is encountered in 1–3% of pancreaticoduodenectomy operations.3

There is a need to identify these variations, and the routine use of pre-operative angiography has been proposed.2 However, most surgeons perform angiography only in selected cases, because these unforeseen situations can be recognised and dealt with during surgery. If angiographic studies have not been obtained before surgery, a test occlusion of the GDA, as recommended by Bull et al.,4 should be performed. The hepatic arteries are palpated before and after occlusion. In the occasional situation where the pulse in the hepatic artery diminishes during occlusion, the GDA should be preserved or revascularised. Various methods have been proposed to deal with this problem, from use of a vein graft to re-implantation of the celiac trunk into the aorta.5 An upper gastrointestinal surgeon must, therefore, possess, or have access to, adequate vascular surgical skills to deal with such a situation.

Surgical training in many countries has recently undergone major upheaval, and has been shortened considerably. The Modernising Medical Careers document of April 2004 from the UK Department of Health proposes further reductions in the length of training.6 With the adaptation of an abbreviated approach to training, most trainees will super-specialise in one field, with little exposure to other sub-specialities, and insufficient expertise to deal with such eventualities.

Conclusions

As illustrated in the above case, situations that bridge sub-specialties in surgery require a broad experience of surgical skills to solve. Complex operations, such as Whipple's procedure, are in danger of falling beyond the capabilities and sole remit of an upper gastrointestinal surgeon.

Learning points

Vascular anomalies are occasionally encountered unexpectedly during pancreatic surgery.

Pancreatic surgeons must be trained in vascular surgery or have immediate access to colleagues with vascular expertise to be able to deal with such eventualities.

References

- 1.Thompson NW, Eckhauser FE, Talpos G, Cho KJ. Pancreaticoduodenectomy and celiac occlusive disease. Ann Surg. 1981;193:399–406. doi: 10.1097/00000658-198104000-00002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rong GH, Sindelar WF. Aberrant peripancreatic arterial anatomy. Considerations in performing pancreatectomy for malignant neoplasms. Am Surg. 1987;53:726–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Trede M. The surgical treatment of pancreatic carcinoma. Surgery. 1985;97:28–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bull DA, Hunter GC, Crabtree TG, Bernhard VM, Putnam CW. Hepatic ischemia, caused by celiac axis compression, complicating pancreaticoduodenectomy. Ann Surg. 1993;217:244–7. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199303000-00005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Berney T, Pretre R, Chassot G, Morel P. The role of revascularization in celiac occlusion and pancreatoduodenectomy. Am J Surg. 1998;176:352–6. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9610(98)00195-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.UK Strategy Group on behalf of the Department of Health, UK. The next steps – The future shape of Foundation, Specialist and General Practice Training Programmes. Modernising Medical Careers policy document, 15 April 2004 < www.dh.gov.uk/publications>.