Abstract

INTRODUCTION

Emergency hernia surgery is associated with a higher postoperative complication and a less favourable outcome. The aim of this study was to audit emergency presentations of abdominal hernias prospectively in order to identify delays in patient treatment.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Prospective audit was carried out between January and September 2003 of all patients presenting acutely with symptomatic hernias. In total, 55 patients presented, 39 of whom needed surgical intervention. The emergency repairs were compared with a cohort of elective repairs performed in the trust at the same time.

RESULTS

The median age was 77 years (range, 5–92 years; 35 male, 20 female). The distribution of the hernias, requiring surgery, was inguinal (19), para-umbilical (10), incisional (5) and femoral (5). The overall complication rate was 46.2% and the in-patient stay was 4 days (range, 1–49 days). Six patients required small bowel resection. Conservative management was identified as a key contributing factor in the delay of treatment. There was a significant increase in the in-patient stay, the early complication rate and the small bowel resection rate in the emergency repairs.

DISCUSSION

Patients with a symptomatic hernia should be offered elective, surgical repair. Non-operative management is inappropriate for the vast majority of cases, especially when many repairs may be performed with local anaesthetic infiltration. Clinicians should be aware of the high morbidity associated with the emergency repair of abdominal hernias in the elderly.

Keywords: Emergency hernia surgery, Abdominal hernia, Treatment

Considerable variation exists in the treatment of elective abdominal hernias and conservative management is used in elderly patients and those with co-morbidity. However, a significant proportion of hernias require emergency surgery, which is associated with a higher postoperative complication rate than elective surgery and a less favourable outcome.1,2 Since elective hernia surgery can be carried out under regional and local anaesthesia, the appropriateness of a ‘watch-and-wait’ policy is open to question.

The aim of this study was to audit emergency presentations of abdominal hernias prospectively in order to identify delays in patient treatment.

Patients and Methods

Between January and September 2003, all patients presenting acutely to The Royal Gwent Hospital with symptomatic hernias were identified. Patient details were recorded prospectively (by the admitting doctor) onto a specifically designed database.

Details of the presenting symptoms, including site of the hernia, duration of symptoms and whether the patient had previously sought a medical opinion were recorded. Details of the clinical management and outcome, in addition to the results of any laboratory and radiological tests were retrieved from the medical notes. A cohort of 298 patients undergoing elective hernia surgery in the trust within the same period was identified and the notes analysed to compare clinical outcomes.

The primary end-points were early postoperative complications (within 30 days of surgery), small bowel resection and in-patient stay.

Data were analysed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS). Comparisons were made between the emergency and elective groups using a non-parametric Mann-Whitney U-test.

Results

In total, 55 patients presented acutely with problems directly related to hernias. The anatomical sites of the acutely presenting hernias are outlined in Table 1 and the presenting symptoms listed in Table 2. The demographics of the patients undergoing emergency and elective repairs were statistically different (Chi-squared P > 0.05). The emergency group were older (median age elective, 55 years [range 23–78 years]; median age emergency, 77 years [range 50–92 years]) and 57% had an American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) grade of III or greater (Chi-squared test P > 0.05). Thirty-nine patients required surgical intervention, all hernias being non-recurrent. As a reflection of their higher prevalence, inguinal hernias were most commonly encountered. The rate of small bowel resection was highest in patients with femoral hernias.

Table 1.

The anatomical sites of hernias presenting as an emergency

| Anatomical site | Number | Small bowel resection |

|---|---|---|

| Inguinal | 19 | 3 |

| Para-umbilical | 10 | 1 |

| Incisional | 5 | 0 |

| Femoral | 5 | 2 |

Table 2.

Presenting symptoms and signs

| Symptoms/signs | Number (%) |

|---|---|

| Pain | 44 (80) |

| Irreducibility | 37 (67.3) |

| Vomiting | 18 (32.7) |

| Radiological evidence of obstruction | 5 (9) |

Sixteen patients (29%) were assessed and discharged by the surgical team. In all cases, the hernia was assessed for reducibility, cough impulse and tenderness. Four patients were seen with a new presentation of a hernia. These patients were re-assured and given out-patient appointments. The remaining patients were assessed and discharged with symptoms (pain and increase in size) relating to pre-existing inguinal, incisional and para-umbilical hernias. All 16 patients were eventually operated on electively.

Thirty-nine patients (median age, 77 years; range, 55–92 years; 25 male; 14 female) required emergency surgical repair and in 6 (15.3%) patients a small bowel resection was performed. All operations were performed by one of seven middle-grade staff (6 specialist registrars and 1 associate specialist). There were no peri-operative deaths and the overall complication rate was 46.2% (18 patients) and was significantly higher in those patients undergoing small bowel resection (P < 0.05; Table 3).

Table 3.

Early postoperative complications after emergency surgery

| Complication | Number(n = 18 |

|---|---|

| Myocardial infarction | 2 |

| Wound infection | 4 |

| Chest infection | 6 |

| Urinary tract infection | 3 |

| Urinary retention | 3 |

The overall complication rate in the patients undergoing elective hernia surgery within the trust, in the same period, was 3% (P < 0.001). There were no cases of small bowel resection being required for any of the elective hernia repairs. The median in-patient stay in the emergency and elective groups was 4 days (range, 1–49 days) and 1 day (range, 1–12 days), respectively (P < 0.05).

Of the total 39 patients that required acute surgical intervention, 30 (76.9%) had consulted their general practitioner and were aware of the diagnosis. Nine patients had not sought medical advice despite noticing a lump for some time. Of the 30 patients who had consulted their general practitioner, 23 were referred to surgical out-patients and the remaining 7 patients were managed conservatively. The reasons given to patients for non-operative management were age, co-morbidity and a low likelihood of problems with the hernia.

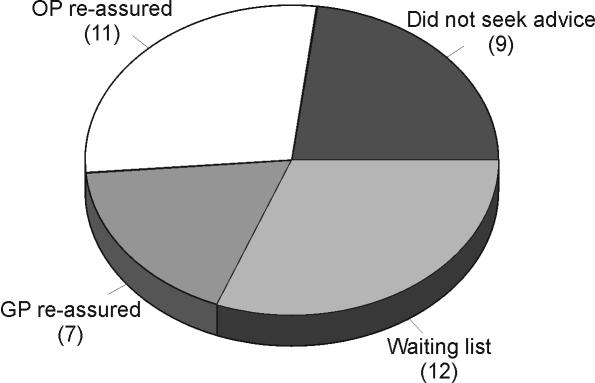

Surgical repair was advised in 12 out of the 23 patients referred to the surgical outpatients. The remaining 11 patients were managed conservatively (Fig. 1). The decision to manage patients conservatively was made by a senior house officer in 3 patients, middle-grade in 4 patients and consultant surgeon in 4 patients. The reasons given to patients for a non-operative approach were again age, comorbidity and a low likelihood of problems with the hernia.

Figure 1.

Reasons for delay in operative repair of abdominal hernias.

Discussion

This study has demonstrated that the complication rate of emergency repair of abdominal hernias is significantly higher than those repaired electively.3–16 In this study, the rate of small bowel resection was 15.3%, which is comparable to published series.8,9 The patients that required emergency repair were elderly and had significant co-morbidity. In addition, the duration of symptoms tended to be longer and often there was delayed hospitalisation. These factors contribute to a less favourable outcome and a prolonged in-patient stay.8,9

Treatment of patients with abdominal hernias is delayed for a number of reasons. A proportion of patients do not seek medical advice after noticing a lump. The reasons for this are outside the scope of this study, but the proportion (around 25%) is relatively constant in the literature.16,17

Most interestingly, the results have demonstrated that a significant proportion of the patients requiring emergency surgery were those being managed conservatively by either the general practitioner or the surgical team. The study has highlighted age, co-morbidity and the low likelihood of the hernia causing problems as being key reasons for nonoperative management.

Age should not be a contra-indication to surgery. Gilbert17 reported on 175 patients over 66 years who underwent elective hernia repair. Over 50% of patients had an ASA grade of III. Most operations were performed under regional or local block with no peri-operative deaths and a low complication rate.17 In 1971, an analysis of Medicare discharges for uncomplicated inguinal hernia demonstrated that 94% of patients underwent repair with a mortality rate of 0.005%. However, the death rate for obstructed hernias was increased 10-fold.18 Both studies reported favourable outcomes if co-morbidity is optimised pre-operatively and reduced in-patient stay if social circumstances planned in advance.

So is there a role for the non-operative management of abdominal hernias? Femoral hernias have between a 40% and 60% rate of strangulation, 10-fold that of inguinal hernias and, therefore, should be repaired urgently.3,5–8 Para-umbilical hernias also have a tendency to incarcerate and strangulate.4 The controversy lies with inguinal hernias. The guidelines of The Royal College of Surgeons of England working party recommended that the repair of asymptomatic, reducible inguinal hernias in the elderly could be safely deferred, as irreducible, indirect hernias are responsible for strangulation in 90% of cases.

However, there is a growing opinion that all inguinal hernias should be repaired whenever possible.3,9–12 This is partly due to the low accuracy (by even the most experienced clinicians) in distinguishing between direct and indirect hernias19 and to the popularisation of repair under local anaesthesia, allowing surgical repair in patients with severe co-morbidity.

The review by Ohana et al.11 in 2004 recommended that patients with asymptomatic inguinal hernia and unfavourable medical conditions should undergo elective repair, preferably under local anaesthesia, in order to avoid the high mortality associated with an emergency operation. In addition, a retrospective review of 147 patients over a 10-year period concluded that elective repair should be considered whenever possible.10

Our hospital has adopted several measures advocated in the running of modern hernia units. All elective in-patient and day-case hernia patients undergo pre-assessment to ensure the appropriateness of the procedure and the fitness of the patient for anaesthesia and high-risk patients are referred to a consultant anaesthetist. Those patients that are medically unfit for general anaesthesia can be offered surgery under spinal or local anaesthesia. However, at present, there is no direct hernia service and patients still have the traditional long wait for a general practitioner's referral to come through. This is unsurprisingly reflected in our results with 12 patients on the waiting list for elective surgery, requiring emergency intervention.9

Conclusions

Elective repair of hernias should be performed whenever possible. In many cases, this can be done under local anaesthesia. Clinicians should be aware of the high morbidity associated with emergency repair of abdominal hernias in the elderly and, if necessary, refer such patients to a surgeon with an interest in hernia surgery.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Mr Ken Harries and Mr Keith Vellacott for their help in the preparation of the manuscript.

Footnotes

SpRs in All Wales Deanery

SpR in Wessex Deanery]

References

- 1.The Royal College of Surgeons of England. Clinical guidelines for the management of groin hernias in adults. London: RCSE; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Perez J, Bardoneldo R, Bear I, Solis J, Alvarez P, Jorge J. Emergency hernia repairs in elderly patients. Int Surg. 2003;88:231–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gallegos N, Dawson J, Jarvis M, Hobsley M. Risk of strangulation in groin hernias. Br J Surg. 1991;78:1171–3. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800781007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mensching J, Musielewicz A. Abdominal wall hernias. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 1996;14:739–56. doi: 10.1016/s0733-8627(05)70277-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wheeler MH. Femoral hernia: analysis of the results of surgical treatment. Proc R Soc Med. 1975;68:177–8. doi: 10.1177/003591577506800312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Waddington R. Femoral hernia: a recent appraisal. Br J Surg. 1971;58:920–2. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800581214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tasker R, Nakatsu K. Femoral hernia: a continuing source of avoidable mortality. Br J Clin Pract. 1982;36:141–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nicholson S, Keane T, Devlin H. Femoral hernia: an avoidable source of surgical mortality. Br J Surg. 1990;77:307–8. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800770323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Malek S, Torella F, Edwards P. Emergency repair of groin herniae: outcome and implication of elective surgery waiting times. Int J Clin Pract. 2004;58:207–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1368-5031.2004.0097.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Alvarez J, Baldonedo R, Bear I, Solis J, Alvarez P, Jorge J. Incarcerated groin hernias in adults: presentation and outcome. Hernia. 2004;8:121–6. doi: 10.1007/s10029-003-0186-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ohana G, Manevwitch I, Weil R, Melki Y, Seror D, Powsner E, et al. Inguinal hernia: challenging the traditional indication for surgery in asymptomatic patients. Hernia. 2004;8:117–20. doi: 10.1007/s10029-003-0184-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kingsnoth A, LeBlanc K. Hernias: inguinal and incisional. Lancet. 2003;362:1561–71. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)14746-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kurt N, Oncel M, Ozkan Z, Bingul S. Risk and outcome of bowel resection in patients with incarcerated groin hernias: retrospective study. World J Surg. 2003;27:741–3. doi: 10.1007/s00268-003-6826-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Andrews N. Presentation and outcome of strangulated external hernia in a district general hospital. Br J Surg. 1981;68:329–32. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800680513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Arenal J, Rodriguez-Vielba, Gallo E, Tinoco C. Hernias of the abdominal wall in patients over the age of 70 years. Eur J Surg. 2002;168:460–3. doi: 10.1080/110241502321116451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McEntee G, O'Carroll A, Mooney B, Egan T, Delaney P. Timing of strangulation in adults hernias. Br J Surg. 1989;76:725–6. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800760724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gilbert A. Hernia repair in the aged and infirmed. J Florida Med Assoc. 1994;75:742–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Milamed D, Hedley-White J. Contributions of the surgical sciences to a reduction of the mortality rate in the United States for the period 1968 to 1988. Ann Surg. 1994;219:94–102. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199401000-00015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ralphs D, Brain A, Grundy D, Hobsley M. How accurately can direct and indirect inguinal hernias be distinguished? BMJ. 1980;280:1039–40. doi: 10.1136/bmj.280.6220.1039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]