Abstract

INTRODUCTION

Ecstasy, also known as MDMA (3,4, methylenedioxymethamphetamine), is a popular illicit party drug amongst young adults. The drug induces a state of euphoria secondary to its stimulant activity in the central nervous system.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

A database review at two major inner city hospitals was undertaken to identify patients presenting with pneumomediastinum and their charts reviewed. A Medline review of all reported cases of pneumomediastinum associated with ecstasy abuse was undertaken.

RESULTS

A total of 56 patients presenting with pneumomediastinum were identified over a 5-year period. Review of the charts revealed a history of ecstasy use in the hours prior to presentation in six of these patients, representing the largest series reported to date.

CONCLUSIONS

Review of previously reported cases reveals the likely mechanism is due to Valsalva manoeuvre during periods of extreme physical exertion, and not a direct pharmacological effect of the drug.

Keywords: Mediastinal emphysema; N-Methyl-3,4-methylenedioxyamphetamine; Ecstasy

Ecstasy, also known as MDMA (N-methyl-3,4-methylenedioxyamphetamine), is a popular illicit party drug amongst young adults. Chemically related to the psychostimulant metamfetamine and the hallucinogen mescaline, the drug induces a state of euphoria secondary to its stimulant activity in the central nervous system. This report outlines a series of six patients who presented to two major inner city hospitals with pneumomediastinum after taking ecstasy. A review of the cases reported in the literature is undertaken.

Patients and Methods

We conducted a retrospective review of all cases of pneumomediastinum presenting to two inner city hospitals over 5 years from January 1999 to December 2004. Inclusion criteria were radiological diagnosis of pneumomediastinum with or without pneumothorax, and a documented history of use of ecstasy in the 24 h prior to presentation. Patient charts were reviewed and information collected on the presenting complaint, pre-existing lung disease, drug use, investigations, treatment and outcome.

A review of the literature was undertaken to identify all previously reported cases of ecstasy associated pneumomediastinum.

Results

Fifty-six patients were identified who had presented to the accident and emergency department with symptoms due to spontaneous pneumomediastinum. Of these patients, six had admitted to ecstasy use in the 24 h prior to presentation. All patients reported taking ecstasy orally. Details of these six patients are outlined in Table 1. Two patients were investigated further with gastrograffin swallow to exclude oesophageal dysfunction. In both cases, there was no evidence of oesophageal leak. All patients were treated conservatively initially with nil orally and intravenous fluids. One patient had a concurrent pneumothorax which was treated with an intercostal catheter. Most patients remained in hospital for only 48–72 h with the patient treated with the intercostal catheter remaining in hospital for 4 days. Images from one patient demonstrating the mediastinal emphysema are shown in Figures 1 and 2.

Table 1.

Details of patients presenting with spontaneous pneumomediastinum and history of ecstasy use

| Patient age (yr) | Gender | Activity | Underlying lung disease | Symptoms | Examination findings | Additional investigations/results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 19 | F | Dancing | Asthma | Shortness of breath | Tachycardia | |

| 21 | F | 24 h at rave | Smoker | Chest pain | Hamman crunch | Normal gastrograffin swallow |

| 21 | F | Rave | Nil | Anxiety; shortness of breath; sore throat; swollen tongue | Tachycardia; subcutaneous emphysema; pericardial rub | Significant pneumothorax on chest X-ray and computed tomography scan |

| 22 | M | Dancing | Nil | Difficulty breathing; chest pain | Subcutaneous emphysema; Hamman crunch | |

| 24 | M | Presented 12 h after dancing | Smoker | Chest pain; swollen neck | Tachycardia; Hamman crunch | Normal gastrograffin swallow |

| 27 | M | Night-club but no vigorous activity reported | Smoker | Chest pain; difficulty breathing; swollen neck | Subcutaneous emphysema |

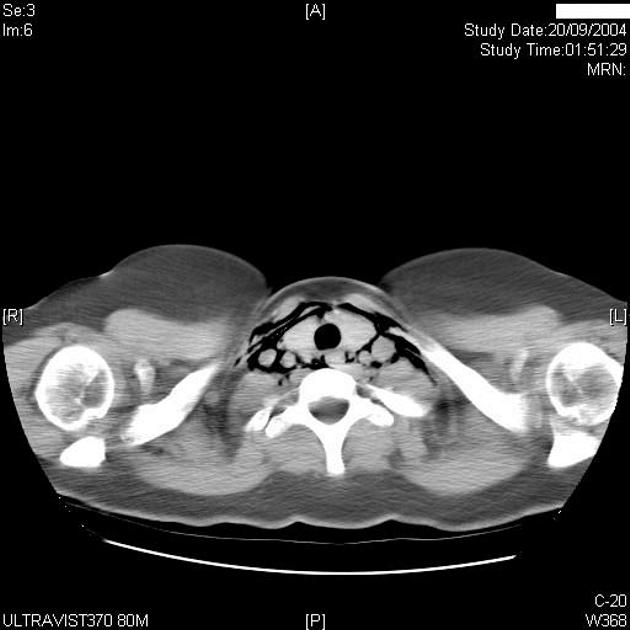

Figure 1.

Pneumomediastinum on computed tomography scan.

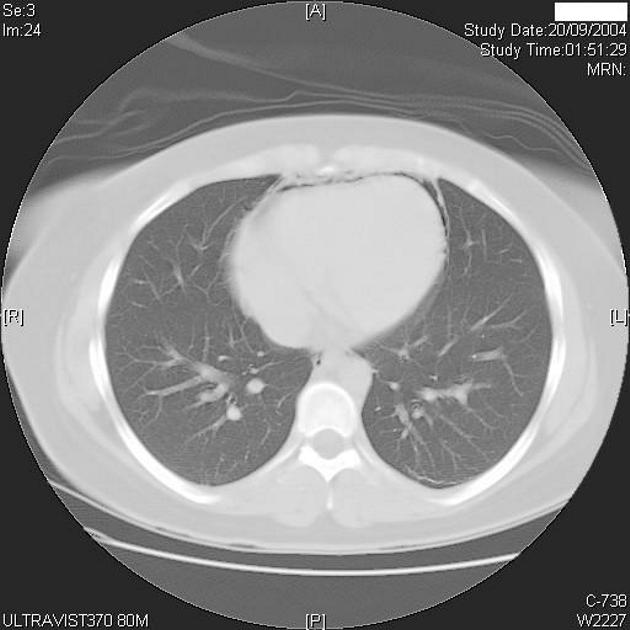

Figure 2.

Pericardial air leading to the classical sign of Hamman's crunch.

A literature review for ecstasy-associated pneumomediastinum was performed. Thirteen previous reports outlining case histories of 15 patients were identified in the world literature dating from 1993 (Table 2).1–13 Eight of the 15 patients underwent gastrograffin swallow to exclude oesophageal dysfunction. One patient had a small tear demonstrated and was treated conservatively.10 All remaining patients were also treated conservatively without any reported sequelae.

Table 2.

Reported cases of ecstasy-associated pneumomediastinum

| Author | Year of report | Patients (n) | Age (years) | History | Symptoms | Examination | Underlying lung disease | Investigations other than chest X-ray |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Levine et al.1 | 1993 | 1 | 17 | Party, vomiting | Chest pain | Tachycardia, subcutaneous emphysema,Hamman's sign | Not reported | Gastrograffin swallow −ve |

| Onwudike2 | 1996 | 1 | 22 | Chest and neck pain | Subcutaneous emphysema | Not reported | Gastrograffin swallow −ve | |

| Rezvani et al.3 | 1996 | 2 | 20 | Retch once | Pleuritic chest pain | Tachycardia, Hamman's sign | Not reported | Echocardiography |

| 18 | Shortness of breath, change in voice | Tachycardia, subcutaneous emphysema | Gastrograffin swallow −ve | |||||

| Pittman & Pounsford4 | 1997 | 1 | 17 | Dancing and blowing whistle for 8 h | Chest pain and neck swelling | Surgical emphysema, Hamman's sign | Non smoker | |

| Quin et al.5 | 1999 | 1 | 25 | Dancing | Chest pain | Not reported | Gastrograffin swallow −ve | |

| Harris & Joseph6 | 2000 | 1 | 20 | Dancing | Dyspnoea and sore throat | Surgical emphysema, Hamman's sign | Asthma | Gastrograffin swallow −ve |

| Ryan et al.7 | 2001 | 1 | 16 | Vomiting | Chest pain and neck swelling | Surgical emphysema | Not reported | |

| Mazur & Hitchcock8 | 2001 | 1 | 18 | 36-h dance party | Chest pain and neck swelling | Surgical emphysema | Not reported | |

| Le Floch et al.9 | 2002 | 1 | 19 | Chest pain, cough | Tachycardia, surgical emphysema | Asthma, smoker | ||

| Rejali et al.10 | 2002 | 2 | 23 | Dancing/vomit once | Neck swelling | Surgical emphysema seen in both patients | Not reported | Gastrograffin swallow −ve |

| 22 | Dancing | Chest pain | Gastrograffin swallow +ve (treated conservatively) | |||||

| Badaoui et al.11 | 2002 | 1 | 27 | Chest pain and shortness of breath | Not reported | Gastrograffin swallow −ve, Bronchoscopy −ve | ||

| Bernaerts et al.12 | 2003 | 1 | 17 | Snorting ecstasy | Chest pain and shortness of breath | Surgical emphysema | Not reported | Computed tomography scan showed epidural pneumatosis |

| Mortelmans et al.13 | 2005 | 1 | 16 | 48-h party | Tachycardia, pyrexia, subcutaneous emphysema | Computed tomography scan, elevated troponin I and creatine kinase, echocardiography, cardiac magnetic resonance imaging |

Discussion

Ecstasy is a popular illicit party drug which is usually taken orally. Chemically related to the psychostimulant metamfetamine and the hallucinogen mescaline, the drug produces stimulant and mild hallucinogenic effects.14 The drug is extremely popular, particularly amongst college-aged students as it is readily accessible and chronic use is not known to be associated with physical dependence. In the US, it has been estimated that more than 10 million people over the age of 12 years have used ecstasy at some time in their lives.15 In the UK, 5% of 16–24-year-olds were reported to have used ecstasy in 2002/2003.16 In comparison, the use of ecstasy is somewhat higher in Australia with a recent poll reporting that 19.7% of 20–29-year-olds have used ecstasy at some time in their lives.17

MDMA is usually taken orally although it can also be crushed and snorted, taken rectally, or injected. It readily crosses the blood–brain barrier and stimulates the central nervous system by releasing serotonin, dopamine and norepinephrine and blocking their re-uptake inactivation.14

The adverse effects of MDMA are mostly due to over-activation of the central and sympathetic nervous systems. These include anxiety, agitation, confusion, psychosis as well as cardiac arrhythmias, seizures, stroke, and sudden death. Hyperthermia is a well-reported, adverse reaction and can lead to disseminated intravascular coagulation, rhabdomyolysis, hepatic and renal failure and death.14 Severe hyponatraemia has also been reported and is thought to be due to either excessive water intake or MDMA-induced secretion of anti-diuretic hormone. The initial symptoms are nausea, vomiting, headache and muscle cramps; in severe cases can lead to seizures and coma. Longer term neuropsychiatric complications include psychosis, depression, anxiety and cognitive impairments particularly in short-term and working verbal memory.14

However, none of these effects explain the propensity to spontaneous pneumomediastinum in young adults who have ingested this drug. It is unlikely that this particular complication is a direct drug effect, and it cannot be explained based on the known pharmacological effects of the drug. Another possibility is a toxic effect of the ‘carrier’ with which the drug is mixed. Given the illicit nature of this drug, the purity of the drug is known to differ widely. In the case report by Rejali et al.,10 where two patients from the same rave party both presented with spontaneous pneumomediastinum, it is conceivable that the MDMA came from the same source and, therefore, contained the same contaminants. However, this hypothesis does not explain the numerous other case reports in the literature.

The most likely cause of spontaneous pneumomediastinum in patients who take MDMA is overexertion and extreme physical activity over prolonged periods. The duration of action of MDMA is 4–6 h and party-goers typically ‘re-dose’ after several hours in order to maintain peak plasma concentrations. Ecstasy use is particularly prevalent during ‘rave’ parties which are organised to continue for 24–48 h. Thus, the drug is used in a party culture where prolonged physical exertion and drug taking defines the social experience.

The mechanism of spontaneous pneumomediastinum is due to a raised intrabronchial and intra-alveolar pressure which occurs due to forced expiration against a closed glottis (Valsalva manoeuvre). When the pressure is raised excessively, alveoli burst and air tracks along bronchovascular fascial planes to reach the mediastinum.18 From there, air will track along the path of least resistance entering the superficial fascial layers of the neck and chest wall causing surgical emphysema. Air may also enter the pericardium (pneumopericardium), pleura (pneumothorax) or the spinal canal causing epidural pneumatosis.12 It is well-known that ecstasy can be crushed and snorted, and presumably this type of administration would increase the risk of pneumomediastinum because of the Valsalva manoeuvre involved. Certainly, pneumomediastinum has been reported as an acute complication of other inhaled illicit drug use.19

Spontaneous pneumomediastinum is an unusual presentation to hospital estimated to occur in 1 in 3400 emergency department admissions.20 It can occur as the result of any activity involving the Valsalva manoeuvre such as coughing, sneezing, vomiting, exercise, childbirth, pulmonary function testing, and has also been reported as a complication of asthma, diabetic ketoacidosis, mechanical ventilation, endotracheal intubation and endoscopy.6,20–23

Although many of the adverse effects of ecstasy use are life-threatening, our series suggests that ecstasy-associated pneumomediastinum is largely benign and resolves spontaneously. All patients in our series were conservatively managed without any adverse outcomes. Our review of all reported cases of ecstasy-associated mediastinum confirms this with all of the reported cases resolving with conservative management. In the patients reviewed, gastrograffin swallow had a poor yield and all patients were managed conservatively regardless of the results.

Conclusions

Ecstasy-associated pneumomediastinum is an emergency room presentation being increasingly reported over the last decade. Observation and conservative management is usually sufficient as all reported cases have resolved without further intervention or sequelae.

References

- 1.Levine AJ, Drew S, Rees GM. ‘Ecstasy’ induced pneumomediastinum. J R Soc Med. 1993;86:232. doi: 10.1177/014107689308600419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Onwudike M. Ecstasy induced retropharyngeal emphysema. J Accid Emerg Med. 1996;13:359–61. doi: 10.1136/emj.13.5.359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rezvani K, Kurbaan A, Brenton D. Ecstasy induced pneumomediastinum. Thorax. 1996;51:960–1. doi: 10.1136/thx.51.9.960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pittman JA, Pounsford JC. Spontaneous pneumomediastinum and ecstasy abuse. J Accid Emerg Med. 1997;14:335–6. doi: 10.1136/emj.14.5.335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Quin GI, McCarthy GM, Harries DK. Spontaneous pneumomediastinum and ecstasy abuse. J Accid Emerg Med. 1999;16:382. doi: 10.1136/emj.16.5.382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Harris R, Joseph A. Spontaneous pneumomediastinum – ‘ecstasy’: a hard pill to swallow. Aust NZ J Med. 2000;30:401–3. doi: 10.1111/j.1445-5994.2000.tb00848.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ryan J, Banerjee A, Bong A. Pneumomediastinum in association with MDMA ingestion. J Emerg Med. 2001;20:305–6. doi: 10.1016/s0736-4679(01)00272-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mazur S, Hitchcock T. Spontaneous pneumomediastinum, pneumothorax and ecstasy abuse. Emerg Med. 2001;13:121–3. doi: 10.1046/j.1442-2026.2001.00190.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Le Floch AS, Lapostolle F, Danhiez F, Adnet F. Pneumomediastinum as a complication of recreational ecstasy use. Ann Fr Anesth Reanim. 2002;21:35–7. doi: 10.1016/s0750-7658(01)00553-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rejali D, Glen P, Odom N. Pneumomediastinum following ecstasy (methylenedioxymetamphetamine, MDMA) ingestion in two people at the same ‘rave’. J Laryngol Otol. 2002;116:75–6. doi: 10.1258/0022215021910230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Badaoui R, Kettani CE, Fikri M, Oeundo M, Canova-Bartoli P, Ossart M. Spontaneous cervical and mediastinal air emphysema after ecstasy abuse. Anesth Analg. 2002;95:1123. doi: 10.1097/00000539-200210000-00071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bernaerts A, Verniest T, Vanhoenacker F, Brande PVd, Petre C, Schepper AMD. Pneumomediastinum and epidural pneumatosis after inhalation of ‘ecstasy’. Eur Radiol. 2003;13:642–3. doi: 10.1007/s00330-002-1466-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mortelmans L, Bogaerts P, Hellemans S, Volders W, Rossom PV. Spontaneous pneumomediastinum and myocarditis following Ecstasy use: a case report. Eur J Emerg Med. 2005;12:36–8. doi: 10.1097/00063110-200502000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ricaurte GA, McCann UD. Recognition and management of complications of new recreational drug use. Lancet. 2005;365:2137–45. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)66737-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. < http://oas.samhsa.gov>.

- 16. < www.dh.gov.uk>.

- 17. < www.adf.org.au>.

- 18.Macklin MT, Macklin CC. Malignant interstitial emphysema of the lungs and mediastinum as an important occult complication in many respiratory diseases and other conditions. Medicine. 1944;23:281–352. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Seaman ME. Barotrauma related to inhalational drug abuse. J Emerg Med. 1990;8:141–9. doi: 10.1016/0736-4679(90)90223-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mihos P, Potaris K, Gakidis I, Mazaris E, Sarras E, Kontos Z. Sports-related spontaneous pneumomediastinum. Ann Thorac Surg. 2004;78:983–6. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2004.03.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Manco JC, Terra-Filho J, Silva GA. Pneumomediastinum, pneumothorax and subcutaneous emphysema following the measurement of maximal expiratory pressure in a normal subject. Chest. 1990;98:1530–2. doi: 10.1378/chest.98.6.1530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Maunder RJ, Pierson DJ, Hudson LD. Subcutaneous and mediastinal emphysema: pathophysiology, diagnosis and management. Arch Intern Med. 1984;144:1447–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Weissberg D, Weissberg D. Spontaneous mediastinal emphysema. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2004;26:885–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcts.2004.05.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]