Abstract

INTRODUCTION

The decision to offer surgical treatment for varicose veins should be based on objective evidence of venous dysfunction and not only the subjective appearance or the reported symptoms. Special tests are required to identify the sub-group of patients with functional superficial venous reflux accurately. The initial test should be simple, cheap, objective, sensitive and easy to perform by a wide range of staff in order to screen out patients without reflux. The final test should be anatomically specific to identify the appropriate surgical procedure. The aim of this study was to test the feasibility of using photoplethysmography (PPG) as the initial test as part of a one-stop vascular clinic assessment protocol.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

All patients referred to one consultant over a 68-week period were assessed using standard practice for the first 22 weeks and with an objective assessment protocol based on PPG for the subsequent 46 weeks.

RESULTS

A total of 347 out-patient appointments for patients with venous disease were booked: 239 (69%) were new referrals. Of the new patients, 59% were CEAP C2/3 and 23% were CEAP C4-6. The introduction of the objective assessment protocol was associated with a reduction in patients offered surgery from 39% to 24% overall and 51% to 28% in new patients with CEAP C2. There was a corresponding increase in the number of patients discharged back to the GP from 19% to 29% overall and 17% to 32%, respectively. The number of patients referred for duplex ultrasound fell slightly from 26% to 22%. Overall, there was a significant change in practice between the two periods (χ2 = 13.3; df = 3; P = 0.004).

CONCLUSIONS

The introduction of an objective assessment protocol based on PPG as the initial objective test reduces the number of patients offered surgery based on objective evidence of venous dysfunction.

Keywords: Venous disease, PPG, Out-patient assessment, Decision on surgery

Varicose veins are the commonest manifestation of venous disease and affect around 20% of the UK population.1 Varicose veins lie towards the milder end of the spectrum of venous disease that culminates in chronic venous insufficiency (CVI) and venous leg ulcers and represent a significant proportion of vascular surgery workload. Despite the wide prevalence of varicose veins, the natural history of the condition is not fully understood. Surgical treatment is offered on the unproven assumption that it will relieve symptoms and reduce the progression towards (CVI). In 1999, Bradbury and colleagues2 showed that there is a poor correlation between the symptoms reported by patients and the severity of venous disease derived from clinical signs and that surgery did not ameliorate symptoms in most patients. A small number of studies have shown some improvement in quality of life after surgery;3,4 however, these studies did not include a control group of patients treated conservatively. This suggests that surgery for varicose veins should not only be based on the reported symptoms and subjective clinical signs, but also based on an objective test of venous dysfunction.

An internationally agreed classification system for venous disease, CEAP,5 and simple, accurate measures of venous dysfunction have only recently become wide-spread; these new tools can now be used to collect more robust evidence for the efficacy of surgery.

Special tests are required to complete the CEAP classification to identify the sub-group of patients with functional superficial venous reflux that is a major contributor to the venous dysfunction and clinical symptoms. The ideal test should be objective, simple, non-invasive, reproducible, sensitive, specific and cheap to administer. The current practice of using clinical examination and hand-held Doppler carries a risk of missing a significant reflux.6 The accepted gold standard test is duplex ultrasound but this is not feasible for all patients because of lack of availability;7 therefore, a selection process based on an initial sensitive test, to exclude normal subjects, and a subsequent specific test should be used. Photoplethysmography (PPG) is a relatively new, objective, non-invasive, cheap, simple and sensitive test that is suitable for use with the majority of patients in the out-patient department.8

The aim of this study was to test the feasibility of an objective venous assessment protocol that includes PPG and which was designed to be used in an out-patient clinic by a range of specialist personnel. The objective was to improve the accuracy of the assessment and, therefore, appropriate management of patients referred with varicose veins. For example, a reduction in the number of patients offered varicose vein surgery might be achieved by identifying those patients with varicose veins that are essentially cosmetic and this would reduce the demand on limited surgical resources.

Patients and Methods

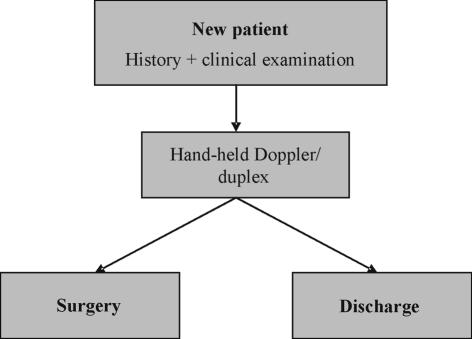

A prospective, observational study was conducted on all patients referred with venous disease to one vascular surgical consultant (SRD) over a 68-week period. For the first 22 weeks of the study (phase 1), a standard protocol based on current accepted practice was used (Fig. 1).7 During the remaining 46 weeks (phase 2), patients were initially assessed by a clinical scientist using the new assessment protocol based on a clinical questionnaire and PPG (Huntleigh Rheo Doppler II, Cardiff, UK; Fig. 2). This technique uses a transducer that emits infrared light into the dermis; the amount of back-scattered light depends on the number of red blood cells on the capillary bed and is measured by a photodetector and displayed as a line tracing.9 After a period of rest, the patient is asked to dorsiflex the foot ten times to exercise the calf muscle pump which partially empties the venous reservoir in the calf and skin. This registers as a change in the infrared absorption of the skin. Venous refill or recovery time is defined as the time required for the PPG tracing to return to 90% of baseline after cessation of exercise and is shorter in a limb with venous reflux. If the venous return time is abnormal (< 25 s), the exercise is repeated with calf or thigh venous tourniquet (60 mmHg) to isolate superficial reflux (protocol in Fig. 2). PPG gives an overall functional assessment of the venous system but limited anatomical information.

Figure 1.

Conventional assessment protocol for symptomatic varicose veins.

Figure 2.

Modified PPG-based objective assessment protocol.

The consultant vascular surgeon reviewed all PPG assessments, decided a management plan and discussed the results with the patient. A report of the assessment and recommended treatment was communicated to the referring GP by letter. Four possible outcomes of the assessment were defined:

Patient discharged to GP: no further investigation or conservative treatment (e.g. compression hosiery) and advice required.

Waiting list: primary symptomatic varicose veins, positive clinical findings and PPG showing groin reflux only. No further tests were required and patients were offered routine venous surgery.

Suspend: symptomatic varicose veins with positive clinical signs and either recurrent veins or PPG evidence of deep or saphenopopliteal reflux that required venous duplex.

Other: patients did not have varicose veins or declined surgery.

Statistical analysis

The effect on outcome of changing the assessment method was tested using the χ2 test of hypothesised proportions with threshold for statistical significance of 0.05.

Results

Over the course of the study, there were 347 out-patient appointments for patients with venous disease, 239 (69%) of whom were new referrals and the others were follow-up appointments after investigations (i.e. venous duplex). Table 1 shows the CEAP classification of new patients by severity of venous disease for each sub-group; two-thirds fall into the CEAP C2/3 classes that represent uncomplicated varicose veins with no clinical evidence of chronic venous insufficiency. Of patients, 23% had evidence of severe venous insufficiency (CEAP grade C4 or worse).

Table 1.

Total number of new out-patient visits over 68 weeks for one consultant (SRD) relating to venous disease classified by CEAP (grade C category)

| CEAP grade | n | % of total |

|---|---|---|

| C0/1 (minor) | 42 | 18 |

| C2/3 (mild) | 141 | 59 |

| C4/5/6 (severe) | 56 | 23 |

| Total | 239 | 100 |

Table 2 shows that, prior to the introduction of the objective assessment protocol, 39% of all patients were offered surgery following their out-patient assessment; after the introduction of the PPG-based protocol, this fell to 24% while at the same time there was an increase in the proportion of patients discharged back to the GP from 19% to 29%. There was a slight fall in the proportion of patients referred for special investigations from 26% to 22%. Overall, there was a significant change in practice between phase 1 and phase 2 (χ2 = 13.3; df = 3; P = 0.004).

Table 2.

Outcomes before and after the introduction of a PPG-based objective assessment protocol (new and follow-up patients)

| Outcome | Phase 1 | Phase 2 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (n) | (%) | (n) | (%) | |

| Discharge to GP | 22 | 19 | 67 | 29 |

| Suspend | 30 | 26 | 51 | 22 |

| Waiting list | 45 | 39 | 56 | 24 |

| Other | 17 | 16 | 59 | 25 |

| Patients seen | 114 | 100 | 233 | 100 |

| Number of weeks | 22 | 46 | ||

Table 3 shows that for the largest group of new patients (CEAP C2), using the standard protocol 51% were offered surgery following their out-patient assessment; after the introduction of the PPG-based objective assessment protocol, this fell to 28%. The number of patients with more complex disease (recurrent varicose veins, history of DVT, or saphenopopliteal reflux) referred for further investigation increased only slightly from 31% to 37%, and the number of patients referred back to the GP without further investigation or surgical treatment nearly doubled from 17% to 32%. There was, again, a significant change in practice between phase 1 and phase 2 in new patients with CEAP C2 (χ2 = 8.06; df = 3; P = 0.045).

Table 3.

Outcome for 134 new patients with CEAP C2 venous disease before and after introduction of the PPG-based objective assessment protocol (7 patients with CEAP 3 excluded)

| Outcome | Phase 1 | Phase 2 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (n) | (%) | (n) | (%) | |

| Discharge to GP | 10 | 17 | 24 | 32 |

| Suspend | 18 | 31 | 28 | 37 |

| Waiting list | 30 | 51 | 21 | 28 |

| Other | 1 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| Patients seen | 59 | 100 | 75 | 100 |

| Number of weeks | 22 | 46 | ||

Discussion

Assuming a population per vascular consultant of about 100,000, the number of new patients seen with venous disease in this study equates to around 95,000 new patients per year for the whole of the UK, resulting in around 50,000 varicose vein operations per year. This agrees with quoted figures,7 indicating that this study sample is likely to be representative. Referral of patients with varicose veins represents a large proportion of vascular surgical out-patients and elective surgical workload. The greater proportion of patients have uncomplicated varicose veins; given that there is a poor association between symptoms and outcome after surgery, limited healthcare resources might be more effectively directed at those patients with objective evidence of more severe venous dysfunction. At the severe end of the spectrum of venous disease, leg ulcers are less common but more expensive to treat and, consequently, consume a disproportionately large proportion of healthcare resources. It is estimated that around half of venous leg ulcers have a surgically treatable cause and treatment of the underlying venous disease offers one way to reduce the recurrence rate.10 The majority of patients referred with varicose veins are found to have uncomplicated truncal venous disease (CEAP C2). If a policy of not offering NHS treatment for cosmetic varicose veins is adopted, the surgical removal of superficial veins is only indicated for the sub-group of patients with functional superficial venous reflux that is a major contributor to the venous dysfunction, clinical symptoms and chronic venous ulcers.

Improved out-patient assessment could reduce the number of patients undergoing further tests and varicose vein surgery by separating those patients with varicose veins that are essentially cosmetic, from those patients with functionally significant reflux who may need specialist investigation and surgical treatment. The different tests for venous disease are complementary and a management protocol that uses the simplest, most sensitive and cheapest test to select those patients who justify the more complex, most specific and expensive tests offers a method for optimising patient selection and more efficient use of diagnostic resources. The use of colour flow Doppler imaging (duplex) in every patient with varicose veins is not feasible as it is a complex measurement technique that uses expensive equipment and personnel only available in a vascular laboratory or radiology department.11,12 On the other end, the use of simple clinical examination and hand-held Doppler carries a high risk of missing a significant proportion of reflux.6

Photoplethysmography (PPG) is a sensitive, objective test that can be performed by non-medical staff using cheap, portable equipment and provides functional information roughly equivalent to the gold-standard ambulatory venous pressure (AVP) measurement.13 When used as part of an assessment protocol, PPG can provide information on the approximate site of reflux and should be complemented by duplex analysis (see Fig. 2). Interpretation of PPG results requires minimal experience but an approximate classification of the type of venous dysfunction can be made on the basis of PPG alone.14

Patients with recurrent varicose veins or more severe venous dysfunction will still require complete assessment with duplex ultrasound but the results of the PPG assessment is useful to direct the examination to particular regions of interest. It is, therefore, better for a vascular technologist to perform the PPG and then to do the duplex assessment at the same visit in those 30% of patients that need it. The use of portable duplex scan in the out-patient clinic could also be implemented by trained personal to improve efficiency.15,16 If a direct booking system were implemented using appropriate referral proformas, a complete one-stop assessment could be offered to all patients with venous disease offering a number of advantages: the patient gets a decision on management after a single visit, even in complex cases, and there is a reduced number of follow-up appointments required with the associated administrative costs.

This problem-specific, rapid-access concept fits well with current trends in the development of improved primary/secondary care relationships: (i) the development of a specialist-led service; (ii) the development of one-stop clinics; and (iii) the use of integrated care pathways and electronic patient referral.

The use of a PPG-based assessment protocol identified sub-groups of patients:

Group C2a CEAP C2 but no measurable venous dysfunction.

Group C2b CEAP C2 with objective evidence of venous dysfunction.

If surgery were only offered to patients with objective evidence of venous haemodynamic impairment, irrespective of symptoms or clinical appearance, the results of this study would suggest that the surgical workload for mild venous disease would be reduced by around 20%. The main limitation of the study was that symptoms were not assessed objectively in patients requiring surgery and a further study to compare symptoms and changes in PPG results would be required to confirm this hypothesis.

It is important to note that PPG only measures local venous haemodynamics near the ankle and not whole limb venous function.17 For example, patients with isolated anterior thigh vein (ATV) reflux and thigh varices may have a normal PPG measurement at the ankle. In our experience, such patients are not common but could be referred for venous duplex and considered as suitable for limited surgery to the ATV.

This higher quality and patient-centred service does come at a cost, which is in providing the necessary equipment and staff trained to perform PPG and venous duplex in the out-patient department and in scheduling the appointments so that all the tests can be performed during a single visit. This cost is, however, outweighed by the more selective use of the expensive surgical resources. A reduction in demand created by objective patient selection based on out-patient PPG measurements would allow existing resources to be redirected to treat those patients who most justify it. Community treatment of venous leg ulcers consumes around 10 times the healthcare resources that varicose vein surgery does (ca £500 million versus £50 million per annum in the UK). The redirection of limited hospital resources to achieving quicker and more durable healing of venous leg ulcers will, therefore, have a far greater social and economic benefit than performing varicose vein surgery on the 50% of patients with mild venous disease and no measurable haemodynamic dysfunction.

Conclusions

The use of an objective assessment protocol using PPG offers a higher quality and more effective service. Further studies are justified to establish the relationship between venous function and reported symptoms and the effect of surgery.

Acknowledgments

The study was funded by a research grant from Good Hope Hospital NHS Trust. The authors would like to acknowledge the technical assistance provided by Ian Jarvis, Chris Collins and Nick McDonnell of the Department of Medical Engineering, Good Hope Hospital NHS Trust and Abigail Dodds for performing the PPG assessments.

References

- 1.Callam MJ. Epidemiology of varicose veins. Br J Surg. 1994;81:167–73. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800810204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bradbury A, Evans C, Allan P, Lee A, Ruckley CV, Fowkes FGR. What are the symptoms of varicose veins? Edinburgh Vein Study Cross Sectional Population Survey. BMJ. 1999;318:353–6. doi: 10.1136/bmj.318.7180.353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Smith JJ, Garratt AM, Guest M, Greenhalgh RM, Davies AH. Evaluating and improving health-related quality of life in patients with varicose veins. J Vasc Surg. 1999;30:710–9. doi: 10.1016/s0741-5214(99)70110-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mackenzie RK, Lee AJ, Paisley A, Burns P, Allan PL, Ruckley CV. Patient, operative, and surgical factors that influence the effect of superficial venous surgery on disease specific quality of life. J Vasc Surg. 2002;36:896–902. doi: 10.1067/mva.2002.128638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Beebe HG, Bergan JJ, Bergqvist D, Eklof B, Eriksson I, Goldman MP, et al. Classification and grading of chronic venous disease in the lower limbs. A consensus statement. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 1996;12:487–91. doi: 10.1016/s1078-5884(96)80019-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rautio T, Perala J, Biancari F, Wiik H, Ohtonen P, Haukipuro K, et al. Accuracy of hand-held Doppler in planning the operation for primary varicose veins. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2002;24:450–5. doi: 10.1053/ejvs.2002.1734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lees TA, Beard JD, Ridler BMF, Szymanska T. A survey of the current management of varicose veins by members of the Vascular Surgical Society. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 1999;81:407–17. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nicoladeis AN. Investigation of chronic venous insufficiency. A consensus statement. Circulation. 2000;102:e126–63. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.102.20.e126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Marston WA. PPG, APG, duplex: which non-invasive tests are the most appropriate for the management of patients with chronic venous insufficiency? Semin Vasc Surg. 2002;15:13–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Scriven JM, Hartshorne T, Bell PRF, Naylor AR, London NJM. Single-visit venous ulcer assessment: the first year. Br J Surg. 1997;84:334–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wills V, Moylan D, Chambers J. The use of routine duplex scanning in the assessment of varicose veins. Aust NZ J Surg. 1998;68:41–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1445-2197.1998.tb04635.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kent PJ, Weston MJ. Duplex scanning may be used selectively in patients with primary varicose veins. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 1998;80:388–93. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Norris CS, Beyray A, Barnes RW. Quantitative photoplethysmography in chronic venous insufficiency: a new method of noninvasive estimation of ambulatory venous pressure. Surgery. 1983;94:758–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Abramowitz HB, Queral LA, Finn WR, Nora PF, Jr, Peterson LK, Bergan JJ, et al. The use of photoplethysmography in the assessment of venous insufficiency: a comparison to venous pressure measurements. Surgery. 1979;86:434–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mekenas LV, Bergan JJ. Venous reflux examination technique: using miniaturized ultrasound scanning. J Vasc Technol. 2002;2:139–44. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kirkby-Bott J, Morrow D, Varty K. Operative vein-mapping for vascular bypass procedures: an early technical report. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2005;87:471–6. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rosfors S. Venous photoplethysmography: relationship between transducer position and regional distribution of venous insufficiency. J Vasc Surg. 1990;11:436–40. doi: 10.1067/mva.1990.17292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]