BACKGROUND

Survival of a total knee arthroplasty is dependent on numerous factors including soft tissue balancing, limb alignment, implant choice, insertion technique and patient activity levels. Poor cementing technique results in reduced shear strengths1 and early failure. Thorough lavage, complete coverage with cement, minimal blood contamination and reduced intramedullary bleeding pressure2 optimise the bone–cement interface. Cement pressurisation and suction techniques are employed to ensure penetration and interdigitation with bone. Pressurisation can be achieved by forcing the knee into extension after insertion of implants;3 however, this has the potential disadvantage of tipping components out of position and does not guarantee penetration. Cement impactors4 ensure superficial cement penetration but are expensive and potentially increase the risk of fat embolism. The suction techniques, e.g. via a Wolf needle,5 reduce both the fat embolism risk and bleeding pressure; however, they can lead to excessive local cement penetration. The method described has the advantages of both techniques and costs a fraction of the amount of the commercially available cement guns.

TECHNIQUE

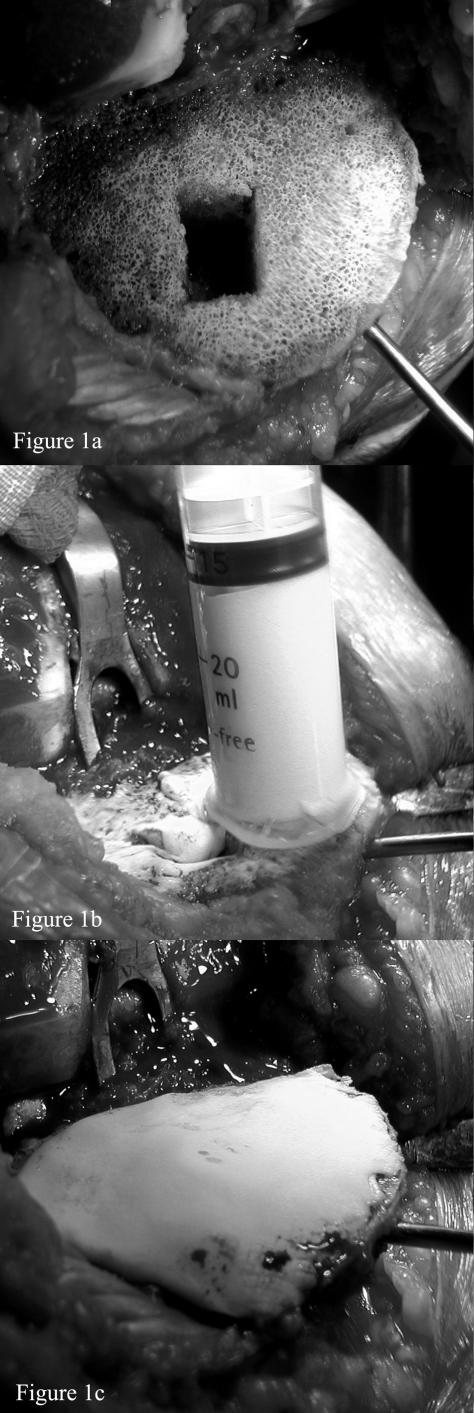

The tibial, femoral and patella surfaces are prepared using standard techniques. A Wolf needle is inserted in the proximal tibia, below the prepared surface and in a position which will not interfere with tibial component insertion (Fig. 1a). Two 20-ml syringes have their plungers removed, their distal ends cut off, and the plungers re-inserted the wrong way around. The cement is drawn up into the syringes. One syringe is used for the tibial surface and one for the femoral and patella surfaces. The collar of the syringe acts as a seal to prevent cement extrusion so that when the plunger is depressed pressure forces cement into the prepared cancellous surface (Fig. 1b). This focal pressurisation process is then repeated over the entire surface of the tibia. Finally, a mantle of cement is applied on the top of the pressurised cement (Fig. 1c) and the prosthesis is inserted. Excessive cement penetration can be avoided by turning off the suction intermittently on the Wolf needle. The process is repeated on the patella and femoral surfaces, with the Wolf needle positioned in either of the femoral condyles.

Figure 1.

(a) Prepared tibial surface prior to cement application note inserted Wolf needle providing suction. (b) Cement is pressurised into tibial surface by a syringe delivery system. (c) Final cement mantle is applied prior to insertion of prosthesis.

This technique can also utilised when performing unicondylar knee replacements; however, one needs to trim the tibial syringe differently to allow for the femoral condyle presence (Fig. 2a). Excellent penetration can still be achieved on both surfaces (Fig. 2b,c).

Figure 2.

(a) Syringes cut for unicondylar cementing. (b) Unicondylar tibial cement pressurisation. (c) Unicondylar femoral cement pressurisation.

DISCUSSION

We believe this is a valuable technique which fulfils all the requirements of a third generation cement insertion method but with negligible cost implications.

References

- 1.Halawa M, Lee AJC, Ling RSM, Vangala SS. The shear strength of trabecular bone from the femur, and some factors affecting the shear strength of the bone cement interface. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 1978;92:19–30. doi: 10.1007/BF00381636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Majkowski KA, Miles AW, Bannister C, Perkins J, Taylor GJ. Bone surface preparation in cemented joint replacement. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1993;75:459–63. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.75B3.8496223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Walker PS, Soudry M, Ewald FC, McVickar H. Control of cement penetration in total knee arthroplasty. Clin Orthop. 1984;185:155–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kim YH, Walker PS, Deland JT. A cement impactor for uniform penetration in the upper tibia. Clin Orthop. 1984;182:206–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Norton MR, Eyres KS. Irrigation and suction technique to ensure reliable cement penetration for total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2000;15:468–74. doi: 10.1054/arth.2000.2965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]