Abstract

INTRODUCTION

We determined whether it is safe to avoid mammograms in a group of symptomatic women with a non-suspicious history and clinical examination.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Symptomatic women aged 35 years or over newly referred to a rapid-diagnosis breast clinic underwent mammography on arrival in the clinic. A breast radiologist reported on the mammograms. An experienced clinician who was unaware of the mammogram findings examined patients and decided whether a mammogram was indicated or not. If not, a management plan was formulated. Mammogram findings were then provided to the clinician and any change to the original management plan as a result of mammography was recorded.

RESULTS

In two-thirds (67%) of 218 patients, the clinician felt a mammogram was indicated. Half (46%) of these mammograms showed an abnormality; of these abnormal mammograms, 41% were breast cancer. Among the third (n = 71) of mammograms felt not to be indicated, 3 showed abnormalities of which 2 were breast cancer. One cancer was not suspected clinically or mammographically but was diagnosed on cyto/histopathological assessment.

CONCLUSIONS

A significant proportion of patients attending a symptomatic breast clinic have a non-suspicious history and normal clinical findings on examination. However, even in this group avoiding mammograms risks missing clinically occult breast cancers. It would appear sensible to offer mammograms to all symptomatic women over 35 years of age.

Keywords: Mammography, Symptomatic, Rapid diagnosis

It is standard practice to assess breast conditions with a combination of clinical examination, imaging, and histo/cytopathological sampling. The establishment of ‘one-stop’ or rapid diagnosis clinics whereby patients undergo this triple assessment at one sitting has been shown to expedite diagnosis and formulation of a management plan by providing the most efficient service.1–3 In areas where such a clinic exists, openaccess, non-screening mammography for general practitioners has been shown to be unnecessary.4 These clinics do, however, incur greater costs per patient than conventional breast clinics.5

Increasingly high numbers of referrals are being seen by these clinics and various measures to improve efficiency and through-put are frequently implemented. Patients over a certain age (usually 35 years) often undergo mammography on arrival at the clinic prior to any clinical examination. Such a policy may result in a number of unnecessary mammograms. The aim of this study was to determine the value of such routine mammography and to see whether it would be safe to avoid mammograms in a group of symptomatic women if an initial clinical assessment by an experienced clinician revealed non-suspicious findings.

Patients and Methods

Patients seen at one consultant surgeon's rapid diagnosis symptomatic breast clinic at the Luton & Dunstable Hospital, Bedfordshire, UK over a 9-month period were studied. Only new symptomatic patients aged 35 years or over who had a mammogram on arrival and assessed by the consultant surgeon were included in the study. Follow-up patients, patients under the age of 35 years and those who did not have a mammogram on arrival (e.g due to pregnancy or severe mastalgia) were excluded. Patients who have had a symptomatic or screening mammogram within the preceding 12 months were not offered mammograms on arrival and, thus, were excluded.

A consultant breast radiologist present in the clinic provided a final written report on the mammograms. The clinician then took a history and examined the patients without access to the mammograms or the report. At the end of examination, the clinician recorded the findings on the data collection sheet and decided whether or not a mammogram was necessary. If a mammogram was felt to be unnecessary, a management plan was formulated (e.g. discharge with re-assurance). Mammograms and the report were then made available to the clinician. Any change in the original management plan as a result of mammographic findings was recorded.

Results

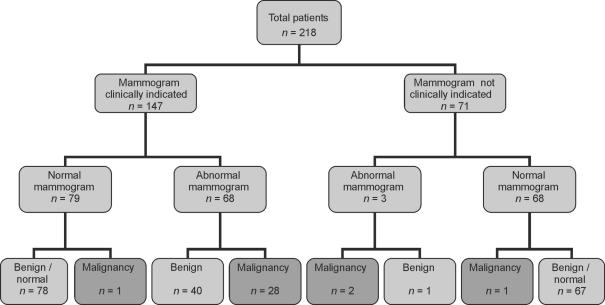

Over a 9-month period, a total of 957 patients were seen in 34 clinics. After excluding the follow-up patients (n = 121) and patients under 35 years of age (n = 204), there were 632 patients aged 35 years or over. Just over a third of these (n = 218) were seen by the consultant following mammography on arrival and were eligible for the study (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Summary of results.

The median age of patients was 48 years (range, 35–85 years) and 95 patients were aged 50 years or over. The most common presenting complaints were: lump (64%), pain (18%) and nipple discharge (6%). Examination found a discrete lump in 31%, a semi-discrete lump or thickening in 25%, nipple discharge in 4%, palpable axillary nodes in 1% and 1% had nipple eczema. A third of patients (35%) had a normal clinical examination of their breasts and axillae.

The clinician considered a mammogram was necessary in 147 cases (67%). Approximately half (46%;, n = 68) of these displayed abnormalities. Twenty-eight (41%) of these abnormal mammograms were later histologically confirmed to show carcinoma (invasive or carcinoma in situ). In the remaining 71 cases (33%), the clinician decided that a mammogram would not be necessary. In this group, only 3 mammograms (4%) revealed abnormalities. Of these abnormalities, two were carcinomas and one was benign. One patient was referred for a benign-looking skin lesion over the left breast and had a punch biopsy of this lesion that confirmed a benign seborrhoeic keratosis. Mammograms showed an incidental impalpable invasive ductal carcinoma of the opposite breast. Another patient who had recently discontinued hormone replacement therapy was referred with breast pain and there was no lump palpable. Mammograms revealed a subtle abnormality behind the left nipple. Stereotactic core biopsies confirmed invasive ductal carcinoma.

One patient with multiple lumpy areas in the breast was thought to have fibrocystic disease on clinical examination. A mammogram was considered necessary but was reported as benign. Fine needle aspiration cytology and subsequent core biopsies showed grade 3 multifocal invasive carcinoma.

Discussion

One primary objective of a symptomatic breast clinic is to avoid missing a malignant lesion. Currently, triple assessment appears to be the best strategy in achieving this aim. While it has been shown to be very reliable,2 triple assessment can occasionally miss malignant disease. In one study, among 42 patients in whom the diagnosis of breast cancer was delayed, 30 had initially undergone triple assessment.6

Mammography is an essential tool in the diagnosis of breast cancer. However, it is not clear whether every patient with breast symptoms (especially those with a normal clinical examination) needs a mammogram. Retrospective studies and audits are difficult to interpret as the clinician's ‘feel’ for the need for further investigations at the time of the examination is difficult to ascertain from case note review. In this study, the clinician was free to choose a mammogram for any reason that he considered necessary. In general, mammograms were requested in: (i) patients with a palpable abnormality; (ii) those with no palpable abnormality but symptoms or signs suspicious of breast cancer (e.g. recent nipple inversion or a contour deformity); and (iii) some patients with normal clinical examination in whom additional re-assurance provided by mammograms was considered to be useful (e.g. those with a family history or anxious patients). In general, only patients with a normal clinical examination and a non-suspicious symptom such as breast pain were considered not candidates for a mammogram.

Recent data from the UK National Breast Screening Programme suggest that, among asymptomatic women aged 50 years or over, mammograms would reveal one carcinoma in every 137 women (assuming all women attending the screening programme were asymptomatic).7 Women referred to a symptomatic breast clinic represent a higher risk group than the screening population and the incidence of mammographically demonstrable carcinoma is much higher in this group.8 The proportion of patients undergoing surgery is higher per mammogram from symptomatic clinics than from breast screening.9 There is a relative paucity of studies on symptomatic mammograms as opposed to screening mammograms. However, the problem of clinically occult breast cancer in symptomatic women has been recognised since the inception of the rapid diagnosis breast clinics.3 In one study, the incidence of mammographically demonstrated clinically occult carcinoma in symptomatic women was 3% and the authors recommended mammograms in all symptomatic women aged over 40 years.10 Our study findings support this recommendation. Another point is that a normal mammogram, even when it is not clinically indicated, provides additional re-assurance to the patient as well as the clinician and thus may be of some benefit.

In this study, the clinician was aware that the patient has had a mammogram and that he would be stopped from discharging the patient if the mammogram had revealed a significant lesion. This might have allowed a certain degree of risk taking in deciding whether a mammogram was necessary or not. However, two-thirds of the patients were considered to be candidates for a mammogram and we do not feel that this factor played a significant part. On the other hand, the incidence of carcinoma in this study population was relatively high (14.7%), as the senior member of the breast team doing the study saw most cancer patients.

Our results suggest that about a third of patients over the age of 35 years attending a rapid-diagnosis, symptomatic, breast clinic could be potentially spared a mammogram as there would be no concerns with regards to the history or clinical findings. Most of these women would have no cancer and most mammograms in this group would be normal. However, despite examination by an experienced breast clinician, the incidence of clinically occult carcinoma demonstrated on mammograms in this group (2.8% in this study) is much higher than that in the screening population as a whole (0.7%).7 Continuing to offer mammograms to all symptomatic women aged 35 years or over would appear to be the safest approach in this regard.

References

- 1.Gui GPH, Allum WH, Perry NM, Wells CA, Curling OM, McLean A, et al. Onestop diagnosis for symptomatic breast disease. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 1995;77:24–7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Eltahir A, Jibril JA, Squair J, Heys SD, Ah-See AK, Need-Ham G, et al. The accuracy of ‘one-stop’ diagnosis for 1,110 patients presenting to a symptomatic breast clinic. J R Coll Surg Edinb. 1999;44:226–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Johansson H, Rimsten A, Stenkvist B, Danielsson J. Organization of a breast tumour clinic and aspects of data analysis of a clinical material. Scand J Soc Med. 1975;3:75–82. doi: 10.1177/140349487500300205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Curtin JJ, Sampson MA. Need for open access non-screening mammography in a hospital with a specialist breast clinic service. BMJ. 1992;304:549–51. doi: 10.1136/bmj.304.6826.549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dey P, Bundred N, Gibbs A, Hopwood P, Baildam A, Boggis C, et al. Costs and benefits of a one stop clinic compared with a dedicated breast clinic: randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2002;324:1–5. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jenner DC, Middleton A, Webb WM, Oommen R, Bates T. In-hospital delay in the diagnosis of breast cancer. Br J Surg. 2000;78:914–9. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2168.2000.01460.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. An Audit of screen detected breast cancers for the year of screening April 2002 to March 2003, NHSBSP, ABS at BASO, 26th May 2004.

- 8.Dee KE, Sickles EA. Medical audit of diagnostic mammography examinations Comparison with screening outcomes obtained concurrently. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2001;176:729–33. doi: 10.2214/ajr.176.3.1760729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Aitkin RJ, Forrest APM, Chetty U, Roberts MM, Huggins A, MacDonald HL, et al. Assessment of non-palpable mammographic abnormalities: comparison between screening and symptomatic clinics. Br J Surg. 1992;79:925–7. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800790923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kerin MJ, O'Hanlon DM, Khalid AA, Kent PJ, McCarthy PA, Given HF. Mammographic assessment of the symptomatic nonsuspicious breast. Am J Surg. 1997;173:181–3. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9610(97)89591-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]