Abstract

INTRODUCTION

The surgical approach to symptomatic pilonidal sinus is open to debate. Many techniques have been described and no single technique fulfils all the requirements of an ideal treatment. Ambulatory treatment with minimal morbidity and rapid return to activity is desirable. The aim of this work was to study the feasibility of day-care surgery for excision and primary asymmetric closure of symptomatic pilonidal sinus.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

All patients referred electively over 2 years were assessed in a single-consultant, colorectal clinic and booked for day-care surgery. All patients had excision and primary asymmetric closure under general anaesthesia in the left lateral position. Whenever possible, they were discharged on the same day according to the day-surgery protocol. Patients were subsequently seen in the out-patient clinic for removal of stitches and were followed up further if there was any wound breakdown.

RESULTS

Fifty-one patients were operated on electively for pilonidal sinus over the 2 years. Two patients were excluded as the final diagnosis was not pilonidal sinus. At 4 weeks following operation, 43 (88%) had complete healing and 6 (12%) had dehiscence of the wound. Recurrence rate was 8% (4 patients) for follow-up of 12–38 months. There was no admission from the day-surgery unit and no unplanned re-admissions. The cost for day-care pilonidal sinus surgery was estimated to be £672.00 per patient compared with in-patient cost of £2405.00.

CONCLUSIONS

Excision and primary asymmetric closure for pilonidal sinus is safe and feasible as day-care surgery and is associated with potential cost saving.

Keywords: Pilonidal sinus, Asymmetric primary closure, Recurrence rate

Pilonidal sinus is a complex, unglamorous chronic sepsis that is often difficult to treat.1 This occurs most commonly in young, hairy males after puberty when sex hormones are known to affect pilosebaceous glands2 and is rare after the age of 40 years.3 Pain (84%) and discharge (78%) are the two most frequent presenting symptoms.4 In sacrococcygeal pilonidal disease, roughly 50% of patients first seek their treatment for acute pilonidal abscess.5 Symptomatic pilonidal sinus is not amenable to conservative treatment – surgery is required.6 The treatment costs for the NHS are significant in terms of surgical procedure, medication, inpatient stay and postoperative wound care in the community. Loss of earnings due to time taken off is also an important consideration given the young age of the population concerned. Many procedures7–15 have been described for the cure of chronic pilonidal sinus with variable results. However, there is no general consensus of opinion regarding any one method. Ideally, surgery for this benign condition should be minimal resulting in primary wound healing, resolution of sepsis, rapid return to full activity and no recurrence. Therefore, ambulatory treatment that offers rapid return to full activity is preferred over more complex in-patient procedures as long as they are effective.

The present study was conducted to evaluate the feasibility of day-case surgery for excision and primary asymmetric closure of pilonidal sinus including an assessment of surgical outcomes and costs.

Patients and Methods

All patients referred electively with pilonidal sinus during the period January 2002 to February 2004 were assessed in a single-consultant, colorectal clinic and booked for day-care surgery if they satisfied day-surgery anaesthetic criteria. All patients were treated as day-cases. All patients had excision and primary asymmetric closure similar to the Karydakis operation16 under general anaesthetic in the left lateral position. All dissection was done with electrocautery. The wound was infiltrated with 0.5% bupivacaine with 1 in 200,000 adrenaline (Marcaine with adrenaline; Astra Zeneca) and the wound was closed with interrupted 0 polyglactin (Vicryl; Ethicon Inc., Sommerville, NJ, USA) to fat and 2/0 prolene (Prolene; Ethicon Inc.) sutures to the skin without any tension. Two patients had drains placed prior to wound closure owing to the large size of the wound. In both these cases, the drain was removed that evening prior to discharge. Whenever possible, patients were discharged on the same day according to day-care surgery protocol on coamoxiclav (5-day course), diclofenac and codydramol. Stitches were removed in the out-patient clinic after 10–14 days and the wound was assessed. Patients were further followed up if there was any wound breakdown. Cost reference was obtained from the hospital management account department.

Results

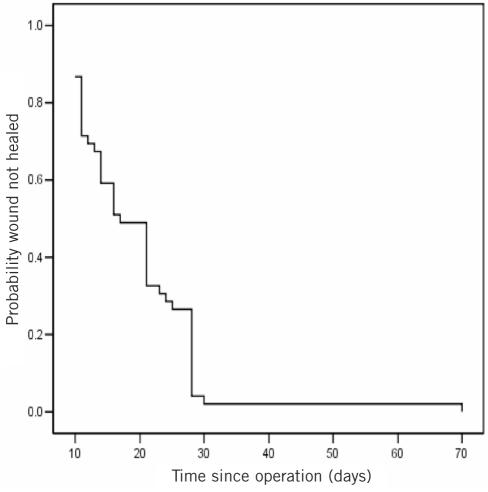

The total number of patients was 51 (male 30, female 21; ratio 4:3; age range 17–53 years; mean, 29 years). Two patients were excluded, as the final histology was not pilonidal sinus. Of 49 patients, 43 (88%) had achieved complete healing within 4 weeks of operation and 6 (12%) failed to achieve healing due to breakdown of the wound. Mean time to healing by secondary intention was 36 days (range, 28–70 days) in these patients. Time to healing is shown in Figure 1. Follow-up was available for 12–38 months. Four patients had recurrence (8%). Other than the 6 patients with wound breakdown, there were no complications. There were no admissions from the daysurgery unit and no unplanned re-admissions. In all, 6 patients had wound breakdown and this was associated with early postoperative infection. The cost for a day-care pilonidal sinus surgery was estimated as £672.00 per patient compared with in-patient cost of £2405.00 for an average hospital stay of 3 days.

Figure 1.

Time to healing.

Discussion

This study comprises a consecutive series of 49 patients over 2 years having surgical treatment for chronic pilonidal sinus under the care of one consultant. All were treated as day-cases, operated in the left lateral position under general anaesthesia using a Karydakis procedure of asymmetric excision of the sinus and primary wound closure. No patient required admission or later re-admission to hospital. Thus the operation was successful as a day-case procedure. The left lateral position permits day-case treatment of patients with a relatively high body mass index, in contrast to the more traditional prone position which some surgeons use for pilonidal sinus surgery.

In order to ascertain wound healing, all patients were brought to the clinic 10–14 days postoperatively for suture removal and, if necessary, repeat shaving. Patients continued to be seen regularly in the clinic if necessary until complete healing was achieved.

In this series, 12% of patients developed wound infection and early breakdown. This compares well with the results of other series of asymmetric closure. Karydakis17 himself had 8.6% failed primary healing, while Bascom18 and Mann and Springall19 reported 13% and 20% failed healing, respectively. Failed primary healing was even higher up to 30%11 in primary midline closure as reported by Allen-Mersh7 in his review paper.

In addition, 8% of patients in this series developed recurrent pilonidal sinus over a follow-up period of 12–38 months. Of these, one patient had early recurrence due to a persistent unhealed wound. Our recurrence rate was more than that of Karydakis17,20 who reported less than 1% recurrence in a series of 7471 patients. Similar results using this technique were reproduced by others.16,21 However, these patients were operated as in-patients and their hospital stay was several days. Our recurrence rate is comparable with other series of asymmetric closure.22,23

Our failed healing was due to wound infection and wound breakdown. Microbiology of the wound swabs revealed significant mixed growth of Staphylococcus aureus, anaerobes and haemolytic Streptococci spp. Our routine use of antibiotics kept overall wound infection at a lower rate compared with 16–30% in previously published series9,11,24 where no antibiotics were used. Suction drains were not routinely used. Meticulous haemostasis, diathermy dissection and a pressure dressing minimised bleeding.

Twenty of our patients achieved primary healing by the time the stitches were removed at 10–14 days. However, 23 patients had a small (< 1 cm) superficial gap in the wound which was allowed to heal by secondary intention. We postulate this may be due to use of diathermy for the skin incision. Since then, we have changed our practice to using a scalpel for the skin incision.

With increasing financial pressure in the NHS, ambulatory treatment is desirable. Patients generally prefer daycase surgery and are at lower risk of hospital-acquired infection in the day-unit. Our day-care policy has fulfilled that and has made a significant financial saving (72% of the in-patient cost). This is in line with the cost of saving reported by Senapati et al.22 in their study of day-case surgery. It will be an important consideration in terms of hospital costs in the NHS where fixed sum will be paid to the hospital for the operation whatever is the actual cost.25

In summary, the key features of this successful day-case surgery were:

Lateral position for operation allowing day-surery for patients with high body mass index.

Primary asymmetric wound closure allowing day-surgery with a low risk of recurrent disease.

Routine use of local anaesthetic infiltration (with adrenaline) diathermy haemostasis and pressure dressing to minimise haematoma without suction drain.

Antibiotic cover.

Close follow-up and wound care to expedite healing.

Conclusions

Excision and primary closure of pilonidal sinus is safe and feasible as day-care surgery. The majority of patients have a satisfactory outcome and there is a potential cost saving for the hospital.

References

- 1.Purkiss SF. Decision making in surgery: a pilonidal sinus. Br J Hosp Med. 1993;50:5546. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Price ML, Grifiths WAD. Normal body hair – a review. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1985;10:87–97. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2230.1985.tb00534.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Clothier PR, Haywood IR. The natural history of the postanal(pilonidal) sinus. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 1984;66:201–3. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kooistra HP. Pilonidal sinuses. Review of the literature and report of three hundred and fifty cases. Am J Surg. 1942;55:3–17. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bascom J. Pilonidal disease: long-term results of follicle removal. Dis Colon Rectum. 1983;26:800–7. doi: 10.1007/BF02554755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nessar G, Kayaab C, Seven C. Elliptical rotation flap for pilonidal sinus. Am J Surg. 2004;187:300–3. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2003.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Allen-Mersh TG. Pilonidal sinus: finding the right track for treatment. Br J Surg. 1990;77:123–32. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800770203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Spivak H, Brooks VL, Nussbaum M, Friedman L. Treatment of chronic pilonidal disease. Dis Colon Rectum. 1996;39:1136–9. doi: 10.1007/BF02081415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sondenaa K, Anderson E, Soreide JA. Morbidity and short term results in a randomised trial of open compared to closed treatment of chronic pilonidal sinus. Eur J Surg. 1992;158:351–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bissett IP, Isbister WH. The management of patients with pilonidal disease – a comparative study. Aust NZ J Surg. 1987;57:939–42. doi: 10.1111/j.1445-2197.1987.tb01298.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Notaras MJ. A review of three popular methods of treatment of postanal (pilonidal) sinus disease. Br J Surg. 1970;57:886–90. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800571204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chintapatla S, Safarani N, Kumar S, Haboubi N. Sacrococcygeal pilonidal sinus: historical review, pathological insight and surgical options. Tech Coloproctol. 2003;7:3–8. doi: 10.1007/s101510300001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Aydede H, Erhan Y, Sakarya A, Kumkumoglu Y. Comparison of three metods in surgical treatment of pilonidal disease. Aust NZ J Surg. 2001;71:362–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Khaira HS, Brown JH. Excision and primary suture of pilonidal sinus. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 1995;77:242–4. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Iesalnieks I, Furst A, Rentsch M, Jauch KW. Primary midline closure after excision of a pilonidal sinuses associated with a high recurrence rate. Chirurg. 2003;74:461–8. doi: 10.1007/s00104-003-0616-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Anyanwu AC, Hossain S, Williams A, Montgomery AC. Karydakis operation for sacrococcygeal pilonidal sinus disease: experience in a district general hospital. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 1998;80:197–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Karydakis GE. New approach to the problem of pilonidal sinus. Lancet. 1973;ii:1414–5. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(73)92803-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bascom J. Repeat pilonidal operations. Am J Surg. 1987;154:118–21. doi: 10.1016/0002-9610(87)90300-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mann CV, Springall R. D-excision for sacrococcygeal pilonidal sinus disease. J R Soc Med. 1987;80:292–5. doi: 10.1177/014107688708000512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Karydakis GE. Easy and successful treatment of pilonidal sinus after explanation of its causative process. Aust NZ J Surg. 1992;62:385–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1445-2197.1992.tb07208.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Patel H, Lee M, Bloom I, Allen-Mersh TG. Prolonged delay in healing after surgical treatment of pilonidal sinus is avoidable. Colorect Dis. 1999;1:107–10. doi: 10.1046/j.1463-1318.1999.00030.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Senapati A, Cripps NPJ, Thompson MR. Bascom's operation in the day-surgical management of symptomatic pilonidal sinus. Br J Surg. 2000;87:1067–70. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2168.2000.01472.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mosquera DA, Quayle JB. Bascom's operation for pilonidal sinus. J R Soc Med. 1995;88:45–6. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Khawaja HT, Bryan S, Weaver PC. Treatment of natal cleft sinus: a prospective clinical and economic evaluation. BMJ. 1992;304:1282–3. doi: 10.1136/bmj.304.6837.1282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Department of Health. Introducing payment by results; the NHS financial reforms. London: Department of Health; 2002. [Google Scholar]