Short abstract

Health professionals are ideally placed to identify domestic violence but cannot do so without training on raising the issue and knowledge of advice and support services

The stigma surrounding domestic violence means that many of those affected are reluctant or do not know how to get help. A systematic review of screening for domestic violence in healthcare settings concluded that although there was insufficient evidence to recommend screening programmes, health services should aim to identify and support women experiencing domestic violence.1 The review highlighted the importance of education and training of clinicians in promoting disclosure of abuse and appropriate responses.1 We argue that a strong case exists for routinely inquiring about partner abuse in many healthcare settings.

Size of problem

Domestic violence includes emotional, sexual, and economic abuse as well as physical violence. The different forms of abuse may occur together or on their own, although always in the context of coercive control by one partner over the other. To reinforce the fact that domestic violence does not necessarily involve physical violence, we prefer the term partner abuse. Abuse can continue after the partners have separated.

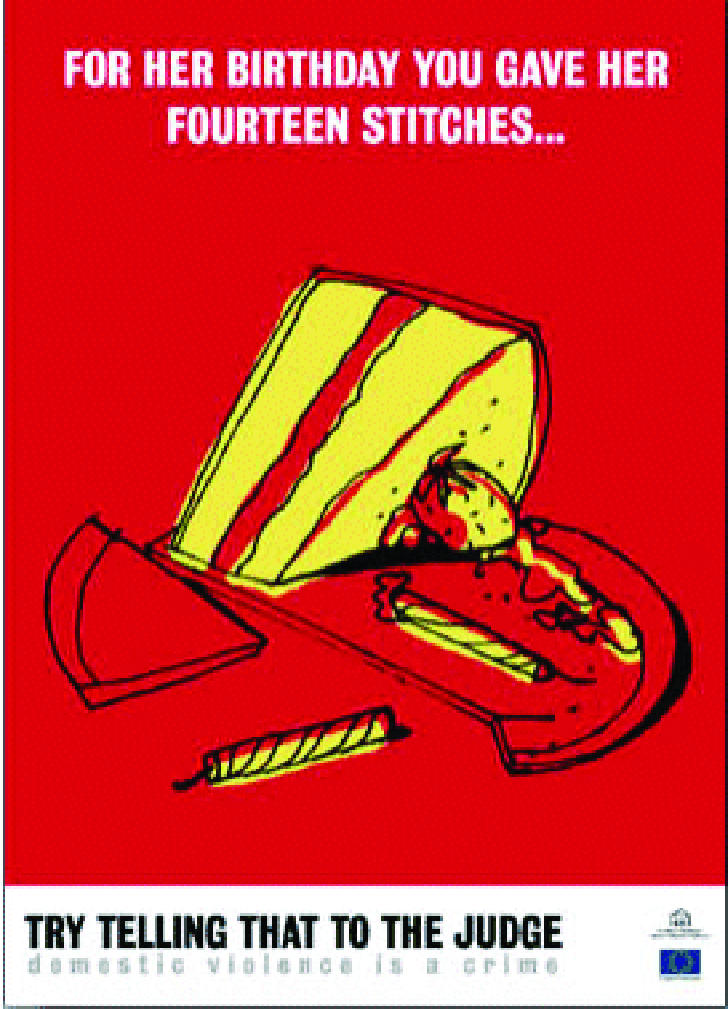

Figure 1.

Partner abuse occurs in all types of relationships, both same sex and heterosexual.2 Although about one in seven men in the United Kingdom report experiencing physical assault by a current or former partner,3 these incidents are generally less serious than those reported by women, and men are less likely to be injured, frightened, or seek medical care.4 The context and severity of violence by men against women makes domestic violence against women a much larger problem in public health terms.2,5 Worldwide, 10-50% of women report having been hit or physically assaulted by an intimate partner at some time.w1 In the United Kingdom, 23% of women aged 16-59 have been physically assaulted by a current or former partner, and two women are killed every week.3 This article therefore focuses on routine inquiry of women accessing health services.

Effects on health

One reason for making domestic violence a health service priority is that it greatly affects the health of those in abusive relationships (box 1). In addition, children growing up with domestic violence are 30-60% more likely to experience child abuse6 w2 w3 and have higher rates of problems such as sleep disturbance, poor school performance, emotional detachment, stammering, suicide attempts, and aggressive and disruptive behaviour.w4-w7 Children who witness domestic violence learn to accept violence as an appropriate method of resolving conflict and are more likely to repeat patterns in adulthood.w8

Routine inquiry or screening?

Screening, as defined by the UK National Screening Committee, refers to the application of a standardised question or test according to a procedure that does not vary from place to place. Routine inquiry is a more suitable approach for domestic violence. In routine inquiry, procedures are not necessarily standardised but questions are asked routinely in certain settings or if indicators of abuse arise. Further research is needed to clarify when routine inquiry is appropriate and how best to implement it.

Box 1: Health effects of domestic violence

Injuries from assault

Chronic health problems such as irritable bowel syndrome, backache, and headachesw9

Increased unintended pregnancies, terminations,w10 and low birthweight babiesw11

Higher rates of sexually transmitted infections, including HIVw12

Higher rates of depression, anxiety, post-traumatic stress disorder,w13 self harm, and suicidew9

Why do we need routine inquiry?

Box 2 lists some of the advantages of routine inquiry about partner abuse. The rates of disclosure of abuse without direct questioning in healthcare settings are poor. The high prevalence and health effects of partner abuse therefore make it important for health professionals to ask directly about domestic violence. Pragmatically, routine inquiry is the only way to increase the proportion of women who disclose abuse and who may benefit from intervention. It has a high level of acceptability, both among women who have experienced domestic violence and among those who have not,1,7,8 although a minority of women do not like the idea.1

Health services are the best place for routine inquiry because they have the most frequent and widest contact with the population of all public services. Most women regularly access services such as contraception advice, cervical and breast screening programmes, maternity care, and care for their children. In addition, women experiencing domestic violence access health services more frequently. A Canadian study found that they were three times more likely to access emergency health services than women who had not experienced abuse.9

In the United Kingdom, over 90% of the population comes into contact with primary healthcare services within five years. This places primary healthcare professionals in a unique position to identify women experiencing abuse and empower them to access support by providing information about or referring them to local services. Women report that it is difficult to find out about public and voluntary services for partner abuse.

Box 2: Advantages of routinely inquiring about domestic violence

Uncovers hidden cases of domestic violence

Changes perceived acceptability of violence in relationships

Makes it easier for women to access support services earlier

Changes health professionals' knowledge and attitudes towards domestic violence and helps to reduce social stigma

Helps maintain the safety of women experiencing domestic violence

Health benefits of routine inquiry

Although there is little research measuring women centred outcomes of health service based interventions,1 substantial qualitative evidence indicates the potential health benefits of routine inquiry. Most evaluations of routine inquiry have focused on process indicators, such as the quality of staff training, the number of women asked about domestic violence, referral to support agencies, and documentation. However, several studies have shown the benefit of use of specialised support services for women and children, and routine inquiry enables access to such services.

One study evaluated an advocacy service for women experiencing domestic violence using a randomised design. Women were interviewed six times over two years, and women in the intervention group reported a higher quality of life, decreased difficulty in obtaining community resources, and less violence over time than women in the control group.10 w14

Another study of 200 women who had used domestic violence outreach services, found that 46% were living in situations of domestic violence when they first contacted the service. All of these women reported that the outreach services had helped them to leave the abusive relationship—a valued outcome for them.6 Qualitative evidence of positive outcomes in healthcare settings,8,11 w15 is complemented by studies of specialised support services outside health services.6,12-14 w16 w17

Implementing routine inquiry

The best way to implement a system of routine inquiry depends on the context, including the organisation and capacity of local agencies offering support to women experiencing partner abuse. Women need to be asked about abuse in a non-judgmental manner15 and to receive clear information on service options, especially about agencies offering support or advocacy services, and help with plans to ensure their safety. Health professionals cannot be expected to undertake this task without training.2

Routine inquiry needs to be flexible. Implementation will be more straightforward in situations where staff take structured histories routinely or in the context of concern about child protection issues. For example, the fifth report of the confidential inquiries into maternal deaths (1997-9) recommends that all women are asked about domestic violence at antenatal booking by their midwife and that they should have the opportunity to talk to their midwife without their partner present at least once during pregnancy.16 In some general practices, well women clinics carry out regular health checks on all women registered with the practice, and asking about domestic violence forms part of this check. When time with patients is more limited, however, questioning may be more appropriate when indicators of abuse arise in the consultation or to ascertain the cause of injuries or health problems, such as depression.

Barriers to routine inquiry

Although routine inquiry is more flexible than screening, objections are still likely to be raised.17 One difficulty is the potential risk to the woman being asked about abuse, and interview studies have shown women are concerned about breaches in confidentiality.18 Safety of women who have disclosed to a health professional must be a priority, and we recommend routine inquiry should be done only by those who are properly trained and when protocols that prioritise safety have been established.

Training of health professionals to respond appropriately to women disclosing abuse and increasing their knowledge of local advocacy and support services has been shown to alleviate their concerns about “opening a can of worms” and to encourage professionals to ask about abuse.8,19 Training has also been shown to overcome some of the other barriers to routine inquiry. These include ambivalent attitudes of staff, difficulties in framing questions or seeing the patient alone, recording information, legal implications, confidentiality, child protection concerns, lack of awareness of support services, frustration at survivors' responses, raising expectations of the client, safety, time management, and issues relating to ethnicity and class.7,8,19,20

Time pressure, staff shortages, and problems in sustaining interventions, particularly training, are common in many health settings and require reform at a structural and policy level. We need to appoint local leaders for partner abuse who can provide or coordinate training in all health settings. Although the government has advocated this approach, so far it has not provided any additional resources, targets, or time frames. Action may be easier to achieve if domestic violence forms part of the priorities set for health within local strategic partnerships established by primary care trusts.

Box 3: Resources for women and health professionals

Department of Health. Domestic violence: a resource manual for health care professionals. London: DoH, 2000 (www.doh.gov.uk/domestic.htm)

Women's Aid Federation website (www.womensaid.org.uk)

Data source on domestic violence (www.domesticviolencedata.org)

Professional guidance

British Medical Association. Domestic violence: a health care issue? (www.bma.org.uk/ap.nsf/Content/Domestic+violence:+a+health+care+issue)

Royal College of General Practitioners. Domestic violence: the general practitioners' role. (www.rcgp.org.uk/rcgp/corporate/position/dom_violence)

Royal College of Midwives. Domestic abuse in pregnancy. Position paper 19a. (www.rcm.org.uk/data/info_centre/data/position_papers.htm)

Local information and training manuals

Camden: www.camden.gov.uk/camden/links/equalities/dm_health.htm

Leeds Interagency Project (0113 2349090 or admin@liap.demon.co.uk)

Redbridge and Waltham Forest Domestic Violence Health Project (www.dvhp.org)

Salford (contact Kim Whitehead, 0161-2124450 or kim.whitehead@salford-pct.nhs.uk)

Summary points

Partner abuse is common and affects physical, mental, reproductive, and sexual health

Routine inquiry in healthcare settings can reduce the effects of partner abuse

Routine inquiry is acceptable to women

Inquiry must be accompanied by information on support services and safety planning

Health professionals need training and protocols to establish routine inquiry safely

Implications for practice

Although national and local health policy and practice must develop and evolve alongside future research, the growing evidence of the health effects of domestic violence means the health sector can no longer avoid its responsibility to take partner abuse seriously. Health professionals can play an important part now by identifying women experiencing domestic violence and enabling them to access further support. Box 3 lists some useful resources available in the United Kingdom. The health sector also has a wider role—for example, in raising awareness by displaying information on partner abuse and support services and in promoting non-violent methods of resolving conflict as part of treatment for substance and alcohol abuse.

Supplementary Material

References w1-w17 are available on bmj.com

References w1-w17 are available on bmj.com

Contributors and sources: The authors comprise a diverse range of health professionals and academics. They are all members of the Domestic Violence and Health Research Forum, which meets twice a year to discuss methodological and policy issues and promote research into the health consequences of domestic violence and appropriate interventions in health, social, and voluntary sectors. This article was written in response to concerns about responses to the publication of a systematic review on whether health professionals should screen for domestic violence.

Competing interests: GF's research group could benefit if funding for research into domestic violence was increased.

References

- 1.Ramsey J, Richardson J, Carter YH, Davidson L, Feder G. Should health professionals screen women for domestic violence? Systematic review. BMJ 2002;325: 314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Krug G, Dahlberg L, Mercy J, Zwi A, Lozano Generve R, eds. World report on violence and health. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2002. www5.who.int/violence_injury_prevention/main.cfm?p = 0000000117

- 3.Mirlees-Black C. Domestic violence: findings from a new British crime survey self completion questionnaire. Home Office research study 191. London: Home Office, 1999.

- 4.Department of Health. Domestic violence: a resource manual for health care professionals. London: DoH, 2000. (www.doh.gov.uk/pdfs/domestic.pdf (accessed 11 Mar 2003)

- 5.World Health Organization. Violence against women: a health priority issue. Geneva: WHO, 1997. (FRH/WHD/97.8.)

- 6.Humphreys C, Thiara R. Routes to safety: protection issues facing abused women and children and the role of outreach services. Bristol: Women's Aid Federation of England, 2002.

- 7.Watts S. Evaluation of health service interventions in response to domestic violence against women in Camden and Islington. Reports 1 and 2. London: London Borough of Camden, 2000/2 (www.camden.gov.uk/camden/links/equalities/pdf/interimhealth.pdf and www.camden.gov.uk/camden/links/equalities/pdf/health.pdf, accessed 11 Mar 2003.)

- 8.Taket AR, Beringer A, Irvine A, Garfield S. Evaluation of the CRP violence against women initiative, health projects: final report—exploring the health service contribution to tackling domestic violence. London, Home Office (in press).

- 9.Ratner PA. The incidence of wife abuse and mental health status in abused wives in Edmonton, Alberta. Can J Pub Health 1993;84: 246-9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sullivan C. The community advocacy project: a model for effectively advocating for women with abusive partners. In: Vincent, John P, Ernest N, eds. Domestic violence: guidelines for research-informed practice. London: Jessica Kingsley Publishers, 2000: 126-43.

- 11.Anderson P. Perceptions of women using the support services offered by the domestic violence holistic healthcare project. London: Faculty of Health, South Bank University, 2002. www.sbu.ac.uk/~regeneva/documents/repPAfinalDec02.pdf

- 12.Home Office. Reducing domestic violence: what works? Briefing notes. London: Home Office, 2000. (www.homeoffice.gov.uk/violenceagainstwomen/brief.htm (accessed 11 Mar 2003).

- 13.Humphreys C, Hester M, Hague G, Mullender A, Abrahams H, Lowe P. From good intentions to good practice: mapping services working with families where there is domestic violence. Bristol: Policy Press, 2000.

- 14.Hague G, Malos E. Domestic violence: action for change. 2nd ed. Cheltenham: New Clarion Press, 1998.

- 15.Williamson E. Domestic violence and health: the response of the medical profession. Bristol: Policy Press, 2000.

- 16.Lewis G, ed. Why mothers die 1997-1999: The fifth report of the confidential enquiries into maternal deaths in the United Kingdom. London: RCOG Press, 2001.

- 17.Waalen J, Goodwin MM, Spitz AM, Petersen R, Saltzman LE. Screening for intimate partner violence by health care providers: barriers and interventions. Am J Prev Med 2000;19: 230-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gerbert B, Johnston K, Caspers N, Bleeker T, Woods A, Rosebaum A. Experiences of battered women in health care settings. Women Health 1996;24(3): 1-16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mezey G, Bacchus L, Bewley S, Haworth A. Midwives' perceptions and experiences of routine enquiry for domestic violence. Br J Obstet Gynaecol (in press). [PubMed]

- 20.Harris V. Domestic abuse screening pilot in primary care 2001-2002. Final report. Wakefield: Support and Survival, 2002.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.