Abstract

INTRODUCTION

The objective of this study was to determine the current practice in the management of adult facial soft tissue injuries in patients presenting to UK accident and emergency departments.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Questionnaire study to the lead clinicians of 217 UK emergency departments seeing over 30,000 new patients annually.

RESULTS

There was a 76% response rate. Suturing was the preferred method of closure, with the majority of clinicians preferring 6/0 or 5/0 non-resorbable sutures. Use of a regional nerve block would be considered by a quarter of clinicians, and adrenaline vasoconstrictor by a third. Referral rates ranged from 5–77% for a more complex wound. Maxillofacial services were preferred by 51% of respondents; on-site referral availability was indicated by only 28%, with an average journey of 16 miles for treatment. Up to 30% of clinicians considered prescribing antibiotics after wound closure, with flucloxacillin and co-amoxiclav most commonly suggested. Accident and emergency review rates ranged from 16% to 45%, with most wounds either being referred to the GP or no formal review being suggested.

CONCLUSIONS

The results of this survey suggest that there is considerable variation in the initial management, referral and review of facial wounds in the UK. Further work is required to formulate guidelines for optimal patient care, ideally in conjuncture with the receiving surgical specialties.

Keywords: Facial, Soft tissue, Wounds, Management

Facial wounds are commonly encountered in the emergency department, with their incidence suggested at between 4% and 7% of all accident and emergency attendances.1,2 Many patients are young adults with injuries resultant from falls or assaults and associated with alcohol consumption.1–3 Up to 90% of facial soft tissue injuries have been estimated to be treated within the emergency department, with a wide variety of wound closure methods available to the clinician.2,4

Despite the frequent presentation of facial wounds in the emergency department, the literature contains little evidence for their management and outcome. The objective of this study was to undertake a survey of current management of adult facial soft tissue injuries presenting to UK accident and emergency departments.

Materials and Methods

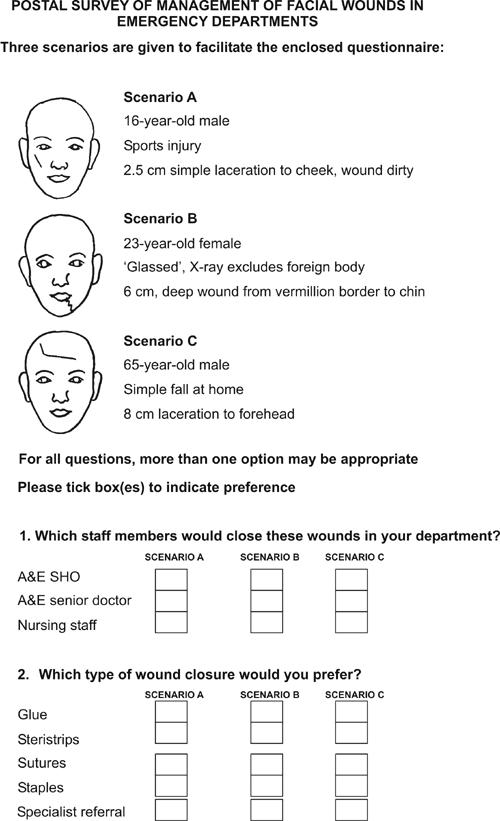

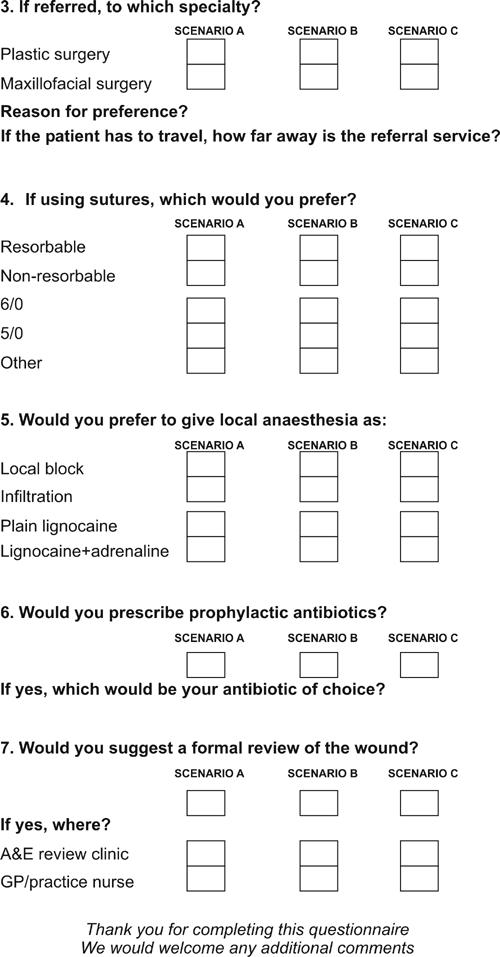

A total of 217 UK accident and emergency departments seeing over 30,000 new patients annually were identified from the British Association for Accident and Emergency Medicine Directory 2001/25 and the lead consultants were sent a questionnaire concerning the theoretical management of three different adult facial wounds.

A pictorial guide and brief description of the scenarios was given (see Appendix):

16-year-old male with a simple but dirty wound over the right cheek.

23-year-old female with a complex wound to the lower lip.

65-year-old male with an extensive laceration to the forehead.

Questions inquired about:

Accident and emergency personnel thought suitable for wound closure

Preferred wound closure methods, including grade and type of sutures

Whether, where feasible, local anaesthesia would be given as a regional block and if adrenaline vasoconstrictor would be used

Would specialist referral be considered, if so, to which speciality and if this was governed by a specific policy

If referral facilities were on site or how far a patient needed to travel

If antibiotic prophylaxis would be prescribed and, if so, which antibiotic would be used

If a wound review was suggested and where this venue should be.

Results

The response rate was 76% (165 of 217).

Table 1 shows the respondents’ views on the accident and emergency personnel thought appropriate to close the wounds in the scenarios posed. In general, SHOs, senior doctors and nursing staff were felt appropriate to close the cheek and forehead wounds. Although a majority of clinicians surveyed felt a senior doctor appropriate to close a complex lip wound, a few felt nursing staff or SHOs suitable to close this type of wound.

Table 1.

Personnel appropriate for wound closure

| Number/165 | (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Scenario A | |||

| SHO | 104 | (63) | |

| Senior doctor | 93 | (56) | |

| Nursing staff | 69 | (42) | |

| Scenario B | |||

| SHO | 18 | (11) | |

| Senior doctor | 106 | (64) | |

| Nursing staff | 9 | (5) | |

| Scenario C | |||

| SHO | 119 | (72) | |

| Senior doctor | 83 | (50) | |

| Nursing staff | 77 | (47) |

Table 2 shows the respondents’ views on wound closure methods for each scenario with the preferred grades of suture shown in Table 3. Only 4% (7/165) of respondents indicated use a resorbable suture material. Sutures were the only method of wound closure thought suitable for the lower lip wound, although other methods were considered for the other two scenarios.

Table 2.

Wound closure methods

| Method | Number | (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Scenario A | Glue | 35 | (21) |

| Steristrips | 66 | (40) | |

| Sutures | 111 | (67) | |

| Staples | 0 | (0) | |

| Scenario B | Glue | 0 | (0) |

| Steristrips | 1 | (0) | |

| Sutures | 165 | (100) | |

| Staples | 0 | (0) | |

| Scenario C | Glue | 15 | (9) |

| Steristrips | 26 | (16) | |

| Sutures | 133 | (81) | |

| Staples | 15 | (9) |

Table 3.

Preferred grade of suture by wound type

| 6/0 | 5/0 | 4/0 or less | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Scenario A | 70 (42%) | 66 (40%) | 1 (0%) |

| Scenario B | 85 (52%) | 48 (29%) | Nil |

| Scenario C | 32 (19%) | 87 (53%) | 28 (17%) |

The respondents’ preference for regional anaesthetic block and type of local anaesthetic is shown in Table 4. A regional nerve block would be considered by a quarter of respondents for a lower lip wound, a fifth for a forehead wound and 10% for a cheek wound. A quarter of respondents would use local anaesthesia with adrenaline for a cheek or lip wound, increasing to 35% for a forehead wound.

Table 4.

Local anaesthesia: methods of administration and type used

| Local nerve block | + Adrenaline | |

|---|---|---|

| Scenario A | 17 (10%) | 38 (23%) |

| Scenario B | 43 (26%) | 45 (27%) |

| Scenario C | 33 (20%) | 57 (35%) |

Table 5 shows the respondents’ views on referral for specialist wound closure. The majority of clinicians would consider referring the complex lip wound but few would refer the other types of wound. A small preference was found for maxillofacial referral. Only a quarter of departments had on-site referral facilities. The average distance travelled by a referred patient was 16.6 miles with some departments indicating a journey of up to 40 miles would be necessary.

Table 5.

Specialist referral: rates and preference

| Number (%) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Number of respondents considering referral | ||

| Scenario A | 25 (15%) | |

| Scenario B | 127 (77%) | |

| Scenario C | 9 (5%) | |

| Preferred speciality | ||

| Maxillofacial surgery | 84 (51%) | |

| Plastic surgery | 68 (41%) | |

| Either | 9 (5%) | |

| No preference stated | 4 (2%) | |

| On-site referral facilities | 47 (28%) | |

| Average distance travelled | 16.6 miles | |

| Maximal journey stated | 40 miles | |

Tables 6 and 7 show the rates and preference of antibiotic prophylaxis. Up to 30% of respondents would consider prescribing antibiotics, with flucloxacillin and co-amoxiclav the most frequently suggested choice of antibiotic.

Table 6.

Rates of antibiotic prophylaxis

| Number (%) | |

|---|---|

| Scenario A | 50 (30%) |

| Scenario B | 21 (13%) |

| Scenario C | 4 (2%) |

Table 7.

Preferred antibiotic therapy

| Number (%) | |

|---|---|

| Flucloxacillin | 32 (19%) |

| Co-amoxiclav | 21 (13%) |

| Penicillin V + flucloxacillin | 6 (4%) |

Respondents’ suggested review rates and venues are shown in Table 8. Some respondents remarked that if they considered a wound suitable for specialist closure, the referral team would be expected to review the wound and had not, therefore, suggested formal departmental wound review.

Table 8.

Wound review rates and venues

| A&E review | GP review | None suggested | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Scenario A | 41 (25%) | 70 (42%) | 54 (33%) |

| Scenario B | 74 (45%) | 29 (18%) | 62 (38%) |

| Scenario C | 27 (16%) | 94 (57%) | 44 (27%) |

Discussion

The results of this survey suggest that there is considerable variation in the current management and referral of facial wounds. The study findings are the opinions of lead consultants and do not necessarily reflect actual practice. There is, however, limited information in the literature to date to record current management of these injuries.

Previous surveys have found that in many accident and emergency departments, facial wound repairs were mainly performed by accident and emergency doctors; however, in around a third of accident and emergency departments, most facial wounds were referred for specialist closure.2,4

However, the role of nursing staff in the accident and emergency department continues to expand, with many regularly undertaking wound closure by a variety of methods, including suturing where appropriate.

In this survey, SHOs and nursing staff were generally felt appropriate to close uncomplicated facial wounds, although more complex wounds were thought best either closed by accident and emergency senior doctors or referred for specialist closure.

Glue and Steristrips are commonly used for closure of well approximated wounds and comparison of wound outcome with glue and sutures has been well documented. The survey by Ong and Dudley2 of emergency care of facial wounds found that, although most wounds to the upper face could be managed with glue or Steristrips, lacerations to the more mobile lower third of the face generally required suturing.

In this survey, respondents considered sutures to be the only appropriate closure method for a complex lower lip wound. Although glue and Steristrips were both considered suitable options for closure of a cheek wound, two-thirds of clinicians would still consider suturing a wound of this type. The forehead wound posed by our scenario was extensive; however, the majority of respondents in this survey suggested they would suture this wound but would also consider stapling, glue and Steristrips as options for closure.

A previous survey found 5/0 or 6/0 non-resorbable monofilament sutures used by over 96% of accident and emergency departments for facial wound suturing.4 We also found the vast majority of respondents in this survey would use either 5/0 or 6/0 sutures, although 4/0 sutures would be considered for a forehead wound. Resorbable sutures were infrequently suggested, in keeping with the finding of Omovie and Shepherd4 that less than 4% of accident and emergency departments were using resorbable suture materials for closure of facial wounds.

Infiltration of local anaesthetic into a wound can produce tissue oedema, which may disrupt anatomical landmarks and produce an overly tight closure causing subsequent necrosis of skin edges; this has been suggested as a significant factor in the development of wound edge necrosis and later wound dehiscence.6

Use of a regional block allows more distant administration of local anaesthetic and may also reduce the total quantity of local anaesthetic required.6,7 Specific regional blocks around the face can be given to anaesthetise the supra-orbital nerve innervating the forehead, the infra-orbital nerve innervating the cheek and the mental nerve supplying the tissues of the lower lip.

In this survey, at most, 26% of respondents would consider using a regional nerve block. It is perhaps disappointing that utilisation of a regional nerve block would not be more widely considered. Further teaching in regional anatomy and placement of blocks may be needed to encourage their use. Use of adrenaline can help gain haemostasis and may aid the visualisation of structures within a wound. We found up to 35% of respondents would consider using local anaesthesia with adrenaline.

Referral rates to specialist services have been previously estimated at between 10% and 30% of the facial wounds presenting to accident and emergency. However, no set protocols for the type or severity of injury necessitating referral have been reported.2,4 Key et al.6 confirmed that shelving injuries and localised tissue cyanosis were associated with delayed wound healing and poor aesthetic scarring. Recognition of these and similar features would help identify wounds likely to benefit from referral.

In this survey, referral rates varied from 5% for a cheek wound to 77% for a complex lip wound. A small majority stated a preference for referral to maxillofacial surgery. Reasons for individual preference included: pressure on an individual service that day, on-site availability of one speciality, and local hospital policy.

Only about a third of accident and emergency departments in this survey had on-site referral facilities. The average distance travelled by a patient to a referral centre was over 16 miles, with several departments having to send patients on an 80 mile round journey. These logistical difficulties can only compound the problems of referring patients, attending out of hours and perhaps inebriated.1,3 Telemedicine has been suggested as a tool for facilitating trauma management but has yet to gain widespread popularity.8

Wound infection rates of up to 7% have been found on review of traumatic injuries.9 Rates of antibiotic prophylaxis varied for each scenario in this survey: 30% would consider prescribing antibiotics for a dirty wound, 13% for a complex lip wound and only 2% for an extensive forehead wound. Specific features of wounds prompting respondents to consider antibiotic prophylaxis included: intra-oral mucosal communication, macroscopically dirty or over 6 hours’ old at presentation. The most commonly suggested antibiotics in this study were flucloxacillin and co-amoxiclav.

Formal wound review in the accident and emergency department was suggested by only 16% of clinicians for the extensive forehead wound and by 25% for the cheek wound. Nearly half the respondents would review the complex lip wound in an accident and emergency clinic, if not already referred on for specialist closure. Additional comments were made that if referral had been suggested, the referral team would be expected to review the wound and formal departmental wound review was not suggested.

Review by the GP was suggested by 42% for the cheek wound, 18% for the complex lip wound and 57% for the forehead wound. The wounds in our scenarios were potentially disfiguring with possible neurological sequelae: few GPs receive training in the management of soft tissue injuries and may not be the most appropriate personnel to provide follow-up. Indeed, instructing patients to arrange for suture removal in 5 days may mean a review with a practice nurse and not a medical practitioner.

Ideally, wounds with minimal risk of complications would be reviewed by GPs with a smaller number of high-risk wounds being reviewed in accident and emergency clinics. We need to be able to identify distinguishing features to select this category of wounds. A unified review policy is probably even more desirable given the range of staff closing facial wounds.

Conclusions

Current management of facial wounds is not standardised. Within this survey, the findings are the opinions of lead consultants and, as such, the results should be interpreted with caution. A variety of personnel were, in this survey, considered suitable to close facial wounds, with a number of wound closure methods available. Nursing staff are expanding their role in wound closure and SHOs may not gain sufficient exposure to allow them to achieve competence in wound management.

By establishing when wounds require referral for specialist closure, we could use referral services in a more coherent manner. Review of facial wounds is not uniform despite possible facial scarring; identification of high-risk wounds could assist in an appropriate use of a review clinic. Antibiotic prophylaxis is also presently random.

Further work is required to formulate guidelines for optimal patient care, ideally in combination with the receiving surgical specialties.

APPENDIX

Postal survey of management of facial wounds in emergency departments

References

- 1.Hutchinson IL, Magennis P, Shepherd JP, Brown AE. The BAOMS United Kingdom Survey of Facial Injuries Part 1: Aetiology and the association with alcohol consumption. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1998;36:3–13. doi: 10.1016/s0266-4356(98)90739-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ong TK, Dudley M. Craniofacial trauma presenting at adult accident and emergency department with an emphasis on soft tissue injuries. Injury. 1999;30:357–63. doi: 10.1016/s0020-1383(99)00101-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shepherd JP, Shapland M, Pearce NX, Scully C. Pattern severity and aetiology of injuries in victims of assault. J R Soc Med. 1990;83:75–8. doi: 10.1177/014107689008300206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Omovie EE, Shepherd JP. Assessment of repair of facial lacerations. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1997;35:237–40. doi: 10.1016/s0266-4356(97)90039-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.British Association of Accident and Emergency Medicine. BAEM Directory. London: BAEM; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Key SJ, Thomas DW, Shepherd JP. The management of soft tissue facial wounds. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1995;33:76–85. doi: 10.1016/0266-4356(95)90204-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Leach J. Proper handling of soft tissue in the acute phase. Fac Plast Surg. 2001;17:227–39. doi: 10.1055/s-2001-18825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jones SM, Milroy C, Pickford MA. Telemedicine in acute plastic surgical trauma and burns. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2004;86:239–42. doi: 10.1308/147870804344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rutherford WH, Spence RA. Infection in wounds sutured in the accident and emergency department. Ann Emerg Med. 1980;9:350–2. doi: 10.1016/s0196-0644(80)80110-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]