Abstract

INTRODUCTION

A prospective study of 300 women of child-bearing age presenting with right iliac fossa pain was carried out to determine what proportion had appendicitis and whether active observation resulted in a delay in diagnosis to the detriment of the patient.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Data were prospectively collected for 300 consecutive women of childbearing age referred with right iliac fossa pain to general surgeons at a district general hospital.

RESULTS

After clinical assessment, 71 were discharged home immediately. Two others were found to be pregnant and 4 admitted to gynaecology. The remaining 223 women were admitted to the general surgical unit, 112 of whom underwent immediate appendicectomy. Of these, 97 had acute appendicitis. Two suffered deep infection and two had a superficial wound infection. A further decision to operate was made in 42 of 111 patients admitted for active observation, with 36 having acute appendicitis and 2 having a carcinoid tumour. Four had a wound infection. The average in-patient stay of those admitted for active observation and not operated on was 2 days (range, 1–4 days) compared with a length of stay of 2 days (range, 1–7 days) for those who underwent ‘immediate’ appendicectomy.

CONCLUSIONS

Most women of child-bearing age who present with right iliac fossa pain do not have appendicitis. Those who do not have the classical features of appendicitis or peritonism can be safely managed by active observation.

Keywords: Appendicitis, Appendicectomy, Abdominal pain

Acute abdominal pain represents the commonest presenting complaint in an acute general surgical ward. Right iliac fossa pain accounts for between a third and a half of all such admissions, with appendicitis being the most common cause.

In women of child-bearing age, there are many gynaecological and obstetric causes of right iliac fossa pain which must be considered. In most units, the current ‘gold standard’ in women where the diagnosis is unclear is active observation with regular re-examination, supplemented by temperature recordings, neutrophil count, urine analysis, pregnancy test and pelvic ultrasound scan.

There has been recent debate over the value of early diagnostic laparoscopy in this group of women. It has been stated that it allows more accurate diagnosis and earlier discharge.1,2 In addition, there is further debate as to what to do with a normal-looking appendix at laparoscopy. Despite recently published evidence to the contrary,3 the consensus is that it should be removed in case there is microscopic or neurogenic appendicitis, faecolith, or undetected carcinoid.4–8

The aim of this study was to assess what proportion of women presenting acutely with right iliac fossa pain have appendicitis and whether observation resulted in a significant delay to the diagnosis.

Patients and Methods

Data were prospectively collected over a 2-year period between 1 September 2001 and 31 August 2003 for 300 consecutive women of child-bearing age referred with right iliac fossa pain to general surgeons at a district general hospital. Most women were referred through their general practitioner. Other referral sources included the accident and emergency department (82), paediatrics (42), and gynaecology (21). The mean age of women treated was 25 years (range, 15–50 years). None had previously been admitted for right iliac fossa pain nor undergone appendicectomy. A diagnosis of appendicitis was made based on history (shifting abdominal pain combined with anorexia), examination (right iliac fossa guarding, low-grade pyrexia). Baseline assessment included full blood count, urine analysis and a pregnancy test. Testing for Chlamydia was restricted to those who were sexually active below the age of 40 years. The majority were admitted to a 6-bedded emergency surgical observation unit immediately adjacent to the accident and emergency department and the radiology department.

Once a working diagnosis was made, the patient either underwent appendicectomy within 12 h of admission, was admitted for active observation (analgesia, intravenous fluids, observation and re-examination), was referred to another specialty or discharged home. The total length of hospital stay was recorded, as were the results of any subsequent investigation, operation and also the final diagnosis. Those who were treated conservatively were traced at 6 months after discharge to determine whether any had subsequent further pain with or without re-admission. The histology reports on all those who underwent appendicectomy were traced.

Results

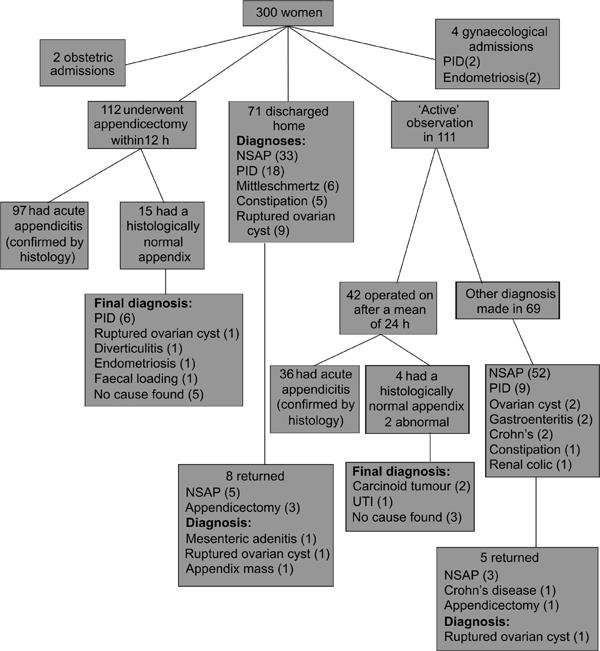

The overall results of outcomes are summarised in Figure 1. Of the 300 women assessed, 6 were referred to a gynaecologist, two were pregnant, 223 were admitted to general surgery and 71 were discharged home. Of these 71 patients, the eventual diagnosis was pelvic inflammatory disease (PID) in 18, ruptured ovarian cyst in 9, Mittleschmertz or mid-cycle pain in 6, constipation in 5 and non-specific abdominal pain in 33.

Figure 1.

Patient flow chart.

A total of 112 women underwent appendicectomy based on initial clinical assessment, with the clinical diagnosis of appendicitis being confirmed histologically in 97 (87%). Fifteen of these were considered to have perforated. The diagnoses of the remaining 15 women included PID (6), ruptured ovarian cyst (1), diverticulitis (1), endometriosis (1), faecal loading (1) and no abnormal findings (5). The length of stay for patients who underwent immediate appendicectomy was 2 days (range, 1–7 days). Two patients suffered deep infections including wound abscess and two had superficial wound infections.

Of those women who did not undergo an operation initially, 111 were admitted for active observation. Ninety-nine underwent ultrasound examination of whom 31 had positive findings. These findings were thickened bowel wall consistent with Crohn's disease (1), free fluid from a ruptured ovarian cyst (4), pyosalpinx (2), fibroid in pregnancy (1), endometriomas (1), and small bowel loops consistent with obstruction secondary to appendix mass (2) and appendicitis (20).

Forty-two of 111 patients admitted for active observation underwent appendicectomy after a mean of 24 h (range, 12–72 h). Thirty-six had histologically proven appendicitis, four of which were perforated. The diagnoses of the remaining patients were carcinoid tumour (2), urinary tract infection (1), and no abnormal findings (3). This gave a positive appendicectomy rate of 88%. Four patients in this group suffered superficial wound infections. The mean length of stay for these 42 women who underwent appendicectomy after a period of observation was 2 days (range, 2–6 days).

In 69 women, pain settled with conservative management. The eventual diagnoses of this group included non-specific abdominal pain (NSAP; 52), PID (9), Crohn's disease (2), ovarian cyst (2), gastroenteritis (2), constipation (1), and renal colic (1). The average inpatient stay for those admitted, but conservatively managed, was 2 days (range, 1–4 days).

Of the 71 women who were immediately discharged, 8 returned for subsequent re-evaluation after a mean of 5 days (range, 2–14 days). Two of these patients had an appendicectomy at this stage. Neither had appendicitis confirmed histologically. Their operative diagnoses were mesenteric adenitis and ruptured ovarian cyst. One had an appendix mass treated conservatively later requiring interval appendicectomy. Of the 69 patients who were treated by active observation and did not undergo surgery, five have had further pain within 6 months. This group included one woman who was subsequently diagnosed to have Crohn's disease and another who eventually underwent an appendicectomy for a ruptured ovarian cyst. No firm diagnosis was reached in the remaining three women.

Discussion

The primary concerns of delaying appendicectomy is a greater perforation rate, with greater morbidity in the short-term potentially leading to late complications such as adhesive obstruction or infertility. Prospective studies have found that delay in patient presentation accounts for the majority of perforated appendices and that indiscriminate appendicectomy to lower perforation rates is not justified.9–11 Female tubal infertility, furthermore, is not directly related to appendicectomy or perforation rates.12,13

Where diagnostic doubt exists, laparoscopy in young women has the advantage of employing minimal access surgery theoretically enabling early discharge with a definitive diagnosis. This is said to be particularly true for patients who are discharged with a diagnosis of non-specific abdominal pain.1,2 In our cohort, the mean length of stay for women actively observed but not operated on was 2 days (range, 1–4 days). This compares favourably with the length of stay after diagnostic laparoscopy for right iliac fossa pain in other series.1,2

Active observation where there is some doubt of the diagnosis in this series rather than immediate appendicectomy for those patients presenting with right iliac fossa pain achieved a low negative appendicectomy rate without increasing the incidence of postoperative complications.7 A correct diagnosis of appendicitis in this study was achieved in 87% of women undergoing immediate appendicectomy, and 88% of women undergoing appendicectomy after a period of active observation. This gave a combined positive appendicectomy rate of approximately 87%, in line with previously published series.7,14

Conclusions

Women of child-bearing age who present with right iliac fossa pain and do not have the classical features of appendicitis and peritonism can be initially managed with active observation. We feel that evidence from this study supports the continuing practice of active observation when the initial diagnosis is not clear.

Acknowledgments

This work was presented, in part, at the Association of Surgeons of Great Britain & Ireland Annual Meeting, Harrogate, April 2004.

References

- 1.Thorell A, Grondal S, Schedvins K, Wallin G. Value of diagnostic laparoscopy in fertile women with suspected appendicitis. Eur J Surg. 1999;165:751–4. doi: 10.1080/11024159950189528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Decadt B, Sussman L, Lewis MP, Secker A, Cohen L, Rogers C, et al. Randomized clinical trial of early laparoscopy in the management of acute non-specific abdominal pain. Br J Surg. 1999;86:1383–6. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2168.1999.01239.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.van den Broek WT, Bijnen AB, de Ruiter P, Gouma DJ. A normal appendix found during diagnostic laparoscopy should not be removed. Br J Surg. 2001;88:251–4. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2168.2001.01668.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chandler B, Beegle M, Elfrink RJ, Smith WJ. To leave or not to leave? A retrospective review of appendectomy during diagnostic laparoscopy for chronic pelvic pain. Modern Med. 2002;99:502–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Al-Ghnaniem R, Kocher HM, Patel AG. Prediction of inflammation of the appendix at open and laparoscopic appendicectomy: findings and consequences. Eur J Surg. 2002;168:4–7. doi: 10.1080/110241502317307490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chiarugi M, Buccianti P, Decanini L, Balestri R, Lorenzetti L, Franceschi M, et al. ‘What you see is not what you get’. A plea to remove a ‘normal’ appendix during diagnostic laparoscopy. Acta Chir Belg. 2001;101:243–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jones PF. Suspected acute appendicitis: trends in management over 30 years. Br J Surg. 2001;88:1570–7. doi: 10.1046/j.0007-1323.2001.01910.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Franke C, Gerharz CD, Bohner H, Ohmann C, Heydrich G, Kramling HJ, et al. Neurogenic appendicopathy: a clinical disease entity? Int J Colorectal Dis. 2002;17:185–91. doi: 10.1007/s00384-001-0363-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Eldar S, Nash E, Sabo E, Matter I, Kunin J, Mogilner JG, Abrahamson J. Delay of surgery in acute appendicitis. Am J Surg. 1997;173:194–8. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9610(96)00011-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Temple CL, Huchcroft SA, Temple WJ. The natural history of appendicitis in adults. A prospective study. Ann Surg. 1996;223:105–6. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199503000-00010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yardeni D, Hirschl RB, Drongowski RA, Teitelbaum DH, Geiger JD, Coran AG. Delayed versus immediate surgery in acute appendicitis: do we need to operate at night? J Pediatr Surg. 2004;39:464–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2003.11.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Urbach DR, Marrett LD, Kung R, Cohen MM. Association of perforation of the appendix with female tubal infertility. Am J Epidemiol. 2001;286:1748–53. doi: 10.1093/aje/153.6.566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Andersson R, Lambe M, Bergstrom R. Fertility patterns after appendicectomy: historical cohort study. BMJ. 1999;318:963–7. doi: 10.1136/bmj.318.7189.963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Flum DR, Morris A, Koepsell T, Dellinger EP. Has misdiagnosis of appendicitis decreased over time? A population-based analysis. JAMA. 2001;286:1748–53. doi: 10.1001/jama.286.14.1748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]