Abstract

INTRODUCTION

Modern delivery of cancer care through patient-centred multidisciplinary teams (MDT) has improved survival. This approach, however, requires effective on-going co-ordination between multiple specialties and resources and can present formidable organisational challenges. The aim of this study was to improve the efficiency of the MDT process for head and neck cancer.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

A systems analysis of the MDT process was undertaken to identify bottlenecks delaying treatment planning. The MDT process was then audited. A revised process was developed and an Intranet-based data management solution was designed and implemented. The MDT process was re-evaluated to complete the audit cycle.

RESULTS

We designed and implemented a trust-wide menu-driven database with interfaces for registering and tracking patients, and automated worklists for pathology and radiology. We audited our MDT for 11 and 10 weeks before and following the introduction of the database, with 226 and 187 patients being discussed during each period. The database significantly improved cross-specialtity co-ordination, leading to a highly significant reduction in the number of patients whose treatment planning was delayed due to unavailability of adjunctive investigations (P < 0.001). This improved the overall efficiency of the MDT by 60%.

CONCLUSIONS

The NHS Cancer Plan aspires to reduce the referral-to-treatment time to 1 month. We have shown that a simple, trust-wide database reduces treatment planning delays in a sizeable proportion of head and neck cancer patients with minimal resource implications. This approach could easily be applied in other MDT meetings.

Keywords: Referral-to-treatment, Waiting times, Cancer patients, Multidisciplinary teams

Cancer of the head and neck is relatively uncommon and accounts for around 3% of new malignancies in the UK.1 As a result, its management has been largely centralised within regional units2 in a similar way to other less common cancers, like those of the upper gastrointestinal region.3 The NHS Cancer Plan stipulates that all patients either with a new diagnosis of cancer, or patients with recurrent or metastatic disease should be discussed within a multidisciplinary team (MDT) meeting.4 ‘Multidisciplinary team working allows patients to benefit from the expertise of a range of specialists for their diagnosis and treatment, and helps ensure that care is given according to recognised guidelines’.4 Robertson et al.5 demonstrated a reduced incidence of tumour recurrence and improved survival in patients with oral cancer seen in a specialist unit with access to an MDT, compared to smaller units.

The efficient running of the head and neck MDT requires co-ordination between multiple surgical specialties including ear nose and throat, plastic and maxillofacial surgery, as well as oncology, pathology and radiology to ensure that all patients are included for discussion in the MDT in a timely manner, and that all the relevant investigations (e.g. radiological imaging and histological specimens) are available to the meeting at the time of discussing a patient.2 This can present a formidable organisational challenge in co-ordinating the input of multiple specialties, and in ensuring that pathology and radiology teams are aware, in good time, of all the patients whose scans and pathological specimens need to be reported in time to be presented at the meeting. Furthermore, since many head and neck patients are referred from peripheral hospitals within the cancer network, it is important to transfer investigations to the regional centre in a timely manner.

Bottlenecks within the MDT process extend the referral-to-treatment waiting time, since treatment cannot commence until a plan has been agreed upon, and a plan cannot be formulated until the MDT is in full possession of the necessary information. Such delays are undesirable in terms of achieving government targets;2,4 but more importantly, because many patients with head and neck cancer present with advanced disease, delays in treatment could worsen their prognosis.6,7 As a result, the NHS Cancer Plan places considerable emphasis on local identification of sources of delay within the system and identifying ways of reducing them.4

In this study, we critically appraised our MDT process to identify potential delays, and assess ways in which our performance could be improved. The findings were used to design and implement a trust-wide database system to coordinate and track new and existing patients. We went on to re-audit the performance of our MDT meeting following the introduction of the database, completing the audit cycle.

Patients and Methods

We performed a systems analysis of the head and neck MDT process. This was accomplished through direct observation, and stake-holder surveys using the Delphi process.8 An audit was undertaken to assess the performance of the MDT meeting over an 11-week period, identifying sources of recurring and potential decision-making delays within the system.

Combining the findings of our systems analysis and the audit we developed a new process for co-ordinating the MDT meeting, and designed a data management application using Microsoft Access to organise and track patients and their investigations throughout the trust. The software was made available to the stake-holders via a secure, shared, Intranet directory.

The performance of the MDT was re-assessed over a further 10-week period following implementation of the database. Both cycles of the audit focused on ‘incomplete MDT episodes’. These were defined as patients who were discussed in consecutive MDT meetings because not all of the necessary pieces of information were available at the time of first discussion. Since our head and neck MDT is a weekly event, any incomplete MDT episode would lengthen the referral-to-treatment timeline by 1 week. The definition of an incomplete MDT episode did not include patients who were re-discussed at the meeting following, for instance, surgical treatment, nor patients whose initial discussion at the MDT highlighted the need for specialist tests, necessitating a further discussion before a treatment decision could be reached. Two observers independently assessed all MDT episodes, identifying repeat discussions, and whether or not they constituted an incomplete MDT episode. The proportion of these episodes was compared between the 11 weeks preceding, and the 10 weeks following the introduction of the database using Fisher's Exact test. The impact of incomplete MDT episodes on overall workload was compared between the two periods using the Mann-Whitney U-test.

Results

The old process

The decision to include a patient for MDT discussion was made by clinicians within several different specialties. Within ear, nose and throat surgery, registrars and consultants communicated the names, medical histories and investigations of each patient to a senior house officer (SHO). This communication was either verbal or via sheets of paper left in the SHO's tray over the course of the week. This information was then collated by the SHO into a Microsoft Word ‘MDT list’, usually 1–2 days before the weekly meeting. The list was e-mailed to stake-holders. Oncologists and other surgical specialties appended their own patients to this list, re-circulating it via e-mail. This process was repeated until all patients were included on the list, typically on the afternoon before the meeting. The pathology and radiology departments used these lists to prepare.

Identifying bottlenecks

There were two largely administrative sources of delay within the MDT process: First, because the final MDT list was often not generated until the day before the meeting, the pathology and radiology departments were being given insufficient time to prepare for the following day's MDT. This made effective work planning difficult, and was particularly an issue for processing tissue specimens taken a short time before the meeting. The second source of delay was in the transfer of outside radiology scans and pathology specimens from peripheral hospitals to our centre. Referrals from peripheral hospitals accounted for 24% of the MDT's workload. The transfer of external material was arranged by the SHOs who were usually made aware of the need to make such requests at the time of compiling the MDT list. The time between preparing the MDT list and the meeting was not always sufficient to allow outside material to be transferred in time. The result of these process bottlenecks was that some patients were included on an MDT meeting, for whom definitive decisions could not be made owing to the lack of one or more pieces of information. These patients then had to be put back on the MDT list for re-discussion the following week, undesirably extending the referral-to-treatment time-span.

Process redesign

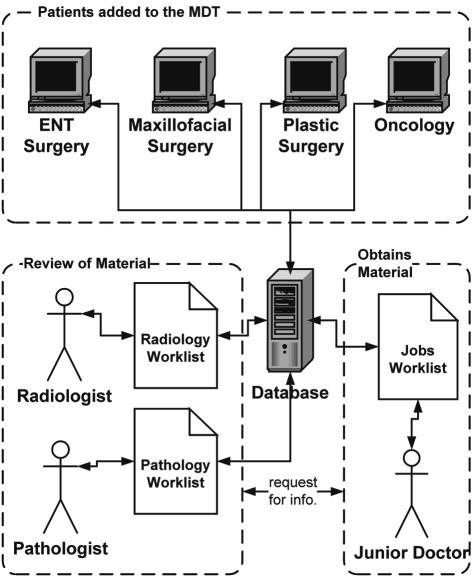

We designed a multi-user automated menu-driven database using Microsoft Access for registering and tracking patient information. The database also generated live interactive worklists for the pathology and radiology departments and the junior medical team (Fig. 1). Furthermore, it produced the weekly MDT list automatically, and had a function to record the MDT's decision for each patient. The database was made available to all head and neck stake-holders via a secure, trust-wide, shared folder. It allowed senior clinicians to register patients directly for the MDT meeting as soon as the decision to include them was made (e.g. in the out-patients clinic or the operating theatre; Fig. 2). In addition, it allowed them to instruct junior staff and the MDT co-ordinator to ‘chase’ various pieces of information (e.g. outside scans) by filling the ‘Tasks’ field within the database (Figs 2 and 3). By generating live pathology and radiology worklists, the database improved workload planning, so that rather than having to wait for a large list of patients to arrive shortly before the meeting, these departments could keep track of MDT requests in real time

Figure 1.

The new database-driven process for organising the MDT meeting.

Figure 2.

A screenshot of the patient registration menu.

Figure 3.

A screenshot of the ‘Pending Tasks’ menu for the junior medical staff and the MDT co-ordinator.

Audit of the MDT process

Over the 21-week period of the audit cycle, 413 patient episodes occurred at our head and neck MDT, 226 before and 187 following introduction of the database. Throughout this period, the most common reason for an incomplete MDT episode was unavailability of pathology results at the time of the meeting (60%), especially for specimens taken close to the date of the meeting. This was followed by unavailability of radiology scans, commonly due to delays in transferring external images to our centre. There were 39 and 13 incomplete MDT episodes before and after introduction of the database, respectively, with over three-quarters of the post-database incomplete episodes occurring within the first 4 weeks of its introduction (Fig. 4). The reduction in the number of incomplete MDT episodes was highly significant (P < 0.001; relative risk 2.48; 95% confidence interval 1.37–4.5; Fisher's Exact test; Fig. 5). It resulted in a fall in the overall number of cases discussed at a meeting from a median of 21 to 18 per week (P < 0.05; Mann-Whitney U-test). This reduction was not due to variations in workload, but could be wholly accounted for by the reduction in the number of incomplete episodes. The overall efficiency of the MDT meeting, defined as the ratio of incomplete to total MDT episodes before and after introduction of the database ([13/187]/[39/226]) improved by 60%.

Figure 4.

Incomplete MDT episodes over the audit cycle.

Figure 5.

Reasons for an incomplete MDT episode before and after the introduction of the database. Miscellaneous reasons included unavailability of key staff and administrative error.

Discussion

In this study, we have shown that a critical appraisal of our MDT process, coupled with the development of a trust-wide database, significantly reduced delays within the MDT process for a sizeable proportion of our patients. This was principally achieved through opening a centralised channel of cross-specialty communication, available to all stakeholders on every trust computer. The database simplified the process of registering patients for the MDT meeting, and produced real-time worklists for pathology and radiology departments, as well as junior medical staff. The net result was improved workflow planning, leading to more patients being processed more quickly.

We recognise that our study concentrates on one aspect of the patient's overall journey of care and that several potential bottlenecks exist within the system. However, the referral-to-treatment waiting time (to which the MDT process contributes) is a particularly distressing period for patients and their families. Moreover, the nature and demography of head and neck cancer is such that patients often present with advanced disease which requires prompt management. It is, therefore, with good reason that the NHS Cancer Plan has placed particular emphasis on this part of the process, aspiring eventually to achieve a maximum 1-month wait from urgent referral to the start of treatment.4

While removing some of the delays in the system, such as access to radiation oncology, 9,10 requires substantial investment in staff and equipment, improvements in the administrative structure of the MDT, which can also significantly reduce treatment delay, is achievable with minimal capital and on-going resource implications. Furthermore, in a set-up that involves input from multiple specialties, an integrated database with an automatically-generated list of currently active patients can only reduce the risk of errors leading to patients being delayed within, or lost to the system.

Conclusions

An efficient MDT is an essential component in a patient's journey of care through cancer treatment. We have shown that a simple information management solution requiring minimal resources can significantly improve the efficiency of the MDT process. This proposed approach is not specific to head and neck oncology, and could be adopted by other multidisciplinary teams. It could also be easily expanded to include audit fields to support the MDT co-ordinator in producing performance reports required by the government, or be incorporated within national clinical databases like the Data for Association of Head and Neck Oncology (DAHNO) project2 to provide seamless administrative support to the MDT.

Acknowledgments

Presented, in part, at a Meeting of the ENT Clinical Audit and Practice Advisory Group (CAPAG), British Association of Otorhinolaryngologists – Head & Neck Surgeons (ENT UK) in September 2006 at The Royal College of Surgeons of England, London, UK.

References

- 1.Quinn M, Babb P, Brock A, Kirby L, Jones J. London: The Stationery Office; 2001. Cancer Trends in England and Wales 1950–1999. Studies on Medical and Population Subjects no. 66. [Google Scholar]

- 2.National Institute for Clinical Excellence. Improving Outcomes in Head and Neck Cancer: The Manual. London: NICE; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Department of Health. Improving outcomes in upper gastro-intestinal cancers: the manual. London: Department of Health; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Department of Health. The NHS Cancer plan: a plan for investment, a plan for reform. London: Department of Health; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Robertson A, Robertson C, Soutar D, Burns H, Hole D, McCarron P. Treatment of oral cancer: the need for defined protocols and specialist centres. variations in the treatment of oral cancer. Clin Oncol. 2001;13:409–15. doi: 10.1053/clon.2001.9303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Teppo H, Koivunen P, Hyrynkangas K, Alho O. Diagnostic delays in laryngeal carcinoma: professional delay is a strong independent predictor of survival. Head Neck. 2003;25:389–94. doi: 10.1002/hed.10208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hansen O, Larsen S, Bastholt L, Godballe C, Jorgensen K. Duration of symptoms: impact on outcome of radiotherapy in glottic cancer patients. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2005;61:789–94. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2004.07.720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.de Meyrick J. The Delphi method and health research. Health Educ. 2003;103:7–16. [Google Scholar]

- 9.National Institute for Clinical Excellence. Improving Outcomes in Head and Neck Cancer: Research Evidence. London: NICE; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Huang J, Barbera L, Brouwers M, Browman G, Mackillop W. Does delay in starting treatment affect the outcomes in radiotherapy? A systematic review. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:555–63. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.04.171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]