Abstract

Transcription of bacteriophage N4 middle genes is carried out by a phage-coded, heterodimeric RNA polymerase (N4 RNAPII), which belongs to the family of T7-like RNA polymerases. In contrast to phage T7-RNAP, N4 RNAPII displays no activity on double-stranded templates and low activity on single-stranded templates. In vivo, at least one additional N4-coded protein (p17) is required for N4 middle transcription. We show that N4 ORF2encodes p17 (gp2). Characterization of purified gp2revealed that it is a single-stranded DNA-binding protein that activates N4 RNAPII transcription on single-stranded DNA templates through specific interaction with N4 RNAPII. On the basis of the properties of the proteins involved in N4 RNAPII transcription and of middle promoters, we propose a model for N4 RNAPII promoter recognition, in which gp2plays two roles, stabilization of a single-stranded region at the promoter and recruitment of N4 RNAPII through gp2-N4 RNAPII interactions. Furthermore, we discuss our results in the context of transcription initiation by mitochondrial RNA polymerases.

Keywords: N4 RNAPII, single-stranded DNA-binding protein, transcriptional activation

Transcription of the 70.6-kb linear double-stranded DNA (dsDNA) N4 genome is regulated through the sequential activity of three distinct RNA polymerases (RNAPs; Zivin et al. 1981). Early transcription is carried out by an N4-coded, rifampicin-resistant, virion-encapsulated RNAP (N4 vRNAP), which is injected into the host with the N4 genome (Falco et al. 1977) and requires the Escherichia coli single-stranded DNA-binding protein for transcription (Markiewicz et al. 1992; Glucksmann-Kuis et al. 1996; Davydova and Rothman-Denes 2003). Transcription of middle genes is dependent on the synthesis of three N4 early proteins, p4, p7, and p17 (Falco and Rothman-Denes 1979a,b; Zehring et al. 1983). Two of these proteins, p4 and p7, comprise a heterodimeric, rifampicin-resistant RNAP (N4 RNAPII; Zehring and Rothman-Denes 1983). Middle genes encode proteins that include N4 replication functions. One of these, the N4 single-stranded DNA-binding protein (N4 SSB), activates the E. coli σ70-holoenzyme at late gene promoters (Cho et al. 1995; Choi et al. 1995; Miller et al. 1997).

Sequence analysis identified N4 RNAPII as belonging to the T7 RNAP family, which includes phage-encoded, mitochondrial, and some chloroplast nuclear-encoded, and linear plasmid-encoded enzymes (Willis et al. 2002). In contrast to the T7-RNAP, N4 RNAPII is inactive on double-stranded, promoter-containing templates, and transcribes single-stranded DNAs (ssDNA), albeit non-specifically and inefficiently (Zehring and Rothman-Denes 1983). A bipartite consensus promoter sequence was derived from comparison of upstream sequences of six in vivo transcription initiation sites (Abravaya and Rothman-Denes 1989b). These sequences are characterized by an AT-rich element, 5′-t/aTTTAa/t-3′, located at the site of transcript initiation. The second element, 5′-At/aGACCTGt/a-3′, is found 12-20bp upstream of the AT-rich element. At present, no functional significance has been ascribed to these two regions.

N4 p17 is a 14.7-kD protein required for RNAPII transcription in vitro and in vivo (Zehring et al. 1983; Abravaya and Rothman-Denes 1989a). In wild-type N4-infected cells, both RNAPII and p17 are found tightly associated with an N4 DNA/inner membrane complex (Falco and Rothman-Denes 1979b; Zehring et al. 1983); however, N4 RNAPII is found in the soluble fraction when an P17 is absent (Zehring et al. 1983). The roles that p17 plays in localization and activation of RNAPII and whether p17 is sufficient for specific transcription initiation are unknown. To elucidate the role of p17 in middle transcription, its gene was identified, sequenced, and cloned. P17, encoded by ORF2, shows no similarities to sequences in the database. The ORF2 product (gp2) was purified to homogeneity and characterized. We show that gp2 is a ssDNA-binding protein that activates transcription through recruitment of N4 RNAPII to ssDNAs, propose a model for N4 RNAPII promoter recognition, and discuss our results in the context of transcription initiation by mitochondrial RNA polymerases.

Results

Identification of ORF2, the gene encoding p17, and purification of the protein

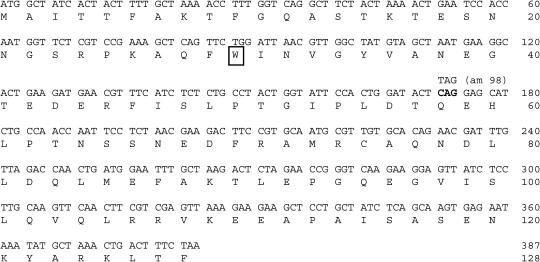

N4 vRNAP transcription of the early gene segment of the N4 genome initiates at three promoters, Pe1, Pe2, and Pe3, which direct the transcription of the four N4 early genes. ORF15 and ORF16, encoding the subunits of N4 RNAPII, are transcribed from Pe3 (Willis et al. 2002). Therefore, ORF1 or ORF2, transcribed from Pe1 and Pe2, respectively, must encode p17. N4am98 phage infection displays a middle transcription-defective phenotype. Only three major proteins, corresponding in size to those encoded by ORF1 (12.3 kD), ORF15 (31.7 kD), and ORF16 (46.4 kD), are produced in N4am98-infected cells, whereas p17 is absent (Fig. 2A, below, lanes 4,5). To identify the gene encoding p17, ORF1 and ORF2 were PCR amplified from both N4 wild-type and N4am98 DNA templates, and the amplicons were sequenced. A single mutation, a C-T transition at nucleotide position 172 in ORF2 generating an amber codon, was detected in N4am98 DNA. Therefore, ORF2 encodes p17 (hereafter named gp2), a 128-amino acid protein of calculated MW 14,284, close to the 14.7 estimated size of p17. The sequence of this protein displays no similarities to sequences in the database (Fig. 1).

Figure 2.

(A) p17 is encoded by ORF2. 35S-labeled proteins were separated by electrophoresis on SDS-PAGE and detected by autoradiography. (Lanes 1-3) Whole cell lysate from W3350(DE3)/pLysS/pSH2. (Lane 1) Uninduced cells. (Lane 2) IPTG-induced cells. (Lane 3) IPTG-induced and rifampicin-pretreated cells. (Lane 4) Rifampicinpretreated cells infected with wild-type phage. (Lane 5) Rifampicin-pretreated cells infected with N4am98 phage. Arrow indicates the position of p17. (B) Recombinant p17 is functional in vivo. Time course of DNA synthesis: (○) W3350cells infected with N4 wild-type phage; (•) W3350cells infected with N4 am98 phage; (□) W3350 (DE3)/pLysS/pSH2 cells pretreated with IPTG 15 min prior to infection with N4am98 phage. (C) Gp2 purification. Protein fractions from different steps of the purification are shown. (Lane 1) A 25% ammonium sulfate supernatant. (Lane 2) Solubilized 50% ammonium sulfate pellet. (Lane 3) Sephacryl S-300 HR eluate. (Lane 4) Hydroxylapatite eluate. (Lane 5) Q-Sepharose eluate. (Lane 6) Final dialysate.

Figure 1.

Sequence of the p17-coding region reveals a 128-amino acid ORF. The N4am98 mutation, a CAG (Gln, amino acid 58)-to-TAG (amber) transition, is bold. The tryptophan (amino acid 30) is boxed.

ORF2 was cloned into plasmid pET11a to create pSH2, and the pattern of protein expression of cells bearing plasmid pSH2 was analyzed after pulse labeling with [35S]methionine and SDS-PAGE (Fig. 2A). An abundant polypeptide of ∼15 kD, absent in uninduced cells (Fig. 2A, lane 1), is produced 30min after induction with IPTG in cells carrying pSH2 (Fig. 2A, lane 2). The 15-kD protein is the major species produced in cells pretreated with rifampicin to inhibit E. coli RNA polymerase-dependent RNA synthesis, as ORF2 is under the control of a T7 RNAP promoter (Fig. 2A, lane 3). These results, in conjunction with the finding that the N4am98 mutation maps to ORF2, confirm that ORF2 encodes p17 (gp2).

We tested whether recombinant gp2 can complement N4am98 phage for middle transcription by assaying for phage DNA synthesis, which requires middle gene products (Fig. 2B). A decrease in DNA synthesis is observed after wild-type N4 infection due to shut-off of host DNA synthesis (Guinta et al. 1986). The rate of DNA synthesis increases ∼10min post-infection as wild-type phage replication begins (Fig. 2B, open circles; Guinta et al. 1986). Infection with N4am98 phage results in a decrease in the rate of DNA synthesis, but no subsequent increase is observed because phage DNA replication cannot occur in the absence of middle transcription (Fig. 2B, filled circles). Expression of recombinant gp2 during N4am98 phage infection results in a DNA synthesis pattern resembling that of wild-type infection, indicating that recombinant gp2 is functional (Fig. 2B, squares).

Hexahistidine-tagging of gp2 resulted in inactive protein, therefore, standard procedures were used to purify the native protein. Gp2 produced in strain BL21(DE3)/pLysS/pSH2 fractionated with the membrane and chromosomal DNA of lysed cells. Sonication, high salt, and/or detergent treatment did not efficiently release soluble active gp2 from the DNA/membrane complex (data not shown); successful release was achieved by DNase I treatment. Solubilized gp2 was purified, and samples from the various purification steps were analyzed by SDS-PAGE (Fig. 2C). A single 15-kD protein was purified to homogeneity.

Gp2 is a single-stranded DNA-binding protein

The association of gp2 with the DNA/membrane complex and its specific release by DNaseI treatment suggested that gp2 is a DNA-binding protein. Purified gp2 did not form complexes with promoter-containing dsDNA in gel mobility-shift assays (data not shown). However, gp2 formed complexes in reactions with either the template or complementary strands of the DNA fragment tested (Fig. 3A). Because of the small amount of labeled ssDNA probe used (<1 nM), the gp2 concentration required for half-maximal binding provides an estimate of the binding constant (Carey 1991). The estimated Kd for ssDNA is ∼30-60 nM. It is worth noting that increasing concentrations of gp2 lead to further retardation of the ssDNA/gp2 complexes.

Figure 3.

Gp2 binds to single-stranded DNA. (A) EMSA of labeled template and complementary strands of the 171-nucleotide Mc fragment (1 nM) and increasing concentrations of gp2. Concentrations of gp2 are as follows: none (lanes 1,10); 8 nM (lanes 2,11); 16 nM (lanes 3,12); 31 nM (lanes 4,13); 62 nM (lanes 5,14); 125 nM (lanes 6,15); 0.25 μM (lanes 7,16); 0.5 μM (lanes 8,17); 1 μM (lanes 9,18). (B) EMSA of reactions containing a labeled 171 nucleotide Mc complementary strand (1 nM) incubated with the indicated amount of nucleic acid competitor prior to addition of gp2. (dsDNA) pBR[Mc]; (RNA) CsCl-purified RNA from N4-infected cells; (ssDNA) M13 mp18 viral DNA. (Lane 1) Free probe. (Lane 2) Probe and gp2. Competitor amounts are as follows: 0.05 ng (lanes 3,9,15); 0.5 ng (lanes 4,10,16); 5 ng (lanes 5,11,17); 50ng (lanes 6,12,18); 0.5 μg (lanes 7,13,19); 5 μg (lanes 8,14,20).

The affinity of gp2 for ssDNA, dsDNA, and RNA was investigated by equilibrium competition experiments (Fig. 3B). ssDNA is a ∼3000-fold more efficient competitor than RNA or dsDNA (Fig. 3B, cf. lanes 8,14,15). Circular M13 viral ssDNA was an efficient competitor of gp2 binding; therefore, binding to the ends of linear DNA is not gp2's predominant binding mode (Fig. 3B, lanes 15-20). The inability of supercoiled plasmid DNA to compete for gp2 binding (data not shown) suggests that torsional stress cannot unwind dsDNA to a sufficient extent for gp2 invasion/interaction. The binding of gp2 to both strands of the fragment tested and the ability of non-N4 ssDNA to effectively compete binding indicate that gp2 is not a sequence-specific ssDNA-binding protein.

To characterize the interaction of gp2 with ssDNA, the quenching of gp2's intrinsic fluorescence upon ssDNA binding was measured (Lohman and Mascotti 1992). The fluorescence emission spectrum of gp2 shows a maximum at 340nm (Fig. 4A), suggesting that a single tryptophan residue (amino acid 30, Fig. 1) is partially solvent exposed (Lakowicz 1983). The fluorescence increased linearly with increasing gp2 concentrations (data not shown).

Figure 4.

Analysis of gp2-nucleic acid binding by fluorescence quenching. (A) Fluorescence spectrum of gp2. Gp2 was present at 250mM in fluorescence buffer containing 300nM NaCl. (B) Gp2 binds preferentially to pyrimidine-containing oligonucleotides. A total of 30base homopolymers were titrated into a solution containing 0.5 μM gp2. (•) [dT]30; (▴) [dC]30; (▪) [dA]30. (C) Dependence of gp2 binding on oligonucleotide length. Poly-[dT] oligonucleotides were titrated into a solution containing 0.25 μM gp2 and 300 mM NaCl. (•) 20 mer; (▴) 30 mer; (▪) 40 mer; (▾) 50mer.

Single-stranded DNA-binding proteins bind DNA in a sequence-independent manner, although they display preferences for certain nucleotide bases (Chase and Williams 1986). To compare the relative affinities of gp2 for oligonucleotide homopolymers of different base composition, fluorescence was measured while 30-base oligonucleotides, [dT]30, [dC]30, or [dA]30, were titrated into a solution containing gp2. The data presented in Figure 4B indicate that gp2 binds [dT1]30> [dC]30 » [dA]30.

The dependence of complex formation on oligonucleotide length was determined by measuring gp2 fluorescence, while [dT]n oligonucleotides of different lengths were titrated into a solution containing gp2. The data were fitted to a plot of fluorescence versus concentration of oligonucleotide added (Fig. 4C). The curve fit of the data indicated that the relative affinities of gp2 for the oligonucleotides are [dT]50= [dT]40 ≥ [dT]30 » [dT]20. A binding site size between 3 and 4 nucleotides per monomer was calculated from the fluorescence titrations with [dT]40and [dT]50(Lohman and Maschotti 1992). The [dT]30oligonucleotide does not produce the same degree of quenching as [dT]40and [dT]50. This is reminiscent of Eco SSB's behavior, in which complexes with a binding stoichiometry of 65 bases per tetramer result in 89% quenching, whereas complexes with 35 bases per tetramer binding mode result in only 53% quenching (Lohman and Overman 1985).

To confirm that the observed fluorescence quenching reflects gp2/ssDNA complex formation, binding reactions containing end-labeled oligonucleotides and increasing amounts of gp2 were analyzed by electrophoretic mobility gel shift assays (EMSA; Fig. 5A). From the fluorescence data, we calculated that 50nM [dT]40or [dT]50 oligonucleotides should be >90% bound by 0.25 μM gp2 (Fig. 4C); however, a lower degree of complex formation was observed in EMSA (Fig. 5A), probably reflecting complex dissociation during electrophoresis. In agreement with the fluorescence data, gp2 did not form a stable complex with the [dT]20 oligonucleotide (Fig. 5A). Gp2/DNA complexes were more stable with longer oligonucleotides (Fig. 5A). Surprisingly, the complex with [dT]30 has lower mobility than the complex with [dT]40 (see Discussion).

Figure 5.

(A) Effect of oligonucleotide length on gp2 binding to ssDNA. Reactions contained 50nM oligonucleotide and gp2 in 300mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 20mM Tris-Cl (pH 8.0). Concentrations of gp2 are as follows: none (lane 1); 0.25 μM (lane 2); 0.50 μM (lane 3); 1 μM (lane 4). (B) Effect of NaCl concentration on gp2 binding to ssDNA. Reactions contained 50nM [dT]40 and 0.75 μM gp2. Gp2 was preincubated for 5 min at the indicated NaCl concentration in 1 mM EDTA, 20mM Tris-Cl (pH 8.0), and the oligonucleotide was added 5 min prior to loading of the gel. Lanes 1 and 2 contained no NaCl; lanes 3-10 contained 0.25, 0.5, 0.75, 1.0, 1.25, 1.5, 1.75, and 2.0 M NaCl, respectively.

The effect of increasing NaCl concentration on gp2 binding could not be determined by fluorescence quenching. Although the fluorescence maximum at 340 nm did not change appreciably during the titration with NaCl, the fluorescence intensity increased reaching a maximum at 0.8 M NaCl (data not shown), suggesting either a change in protein conformation or aggregation state. Therefore, gp2 was incubated with increasing NaCl concentrations prior to addition of poly[dT]40, and the complexes were analyzed by EMSA (Fig. 5B). Gp2 binding to DNA increased as the NaCl concentration increased from 0to 0.75 M. At concentrations above 1 M NaCl, DNA binding decreases.

Recombinant gp2 activates N4 RNAPII transcription on single-stranded DNAs by RNAP recruitment to single-stranded templates

Transcription reactions were performed to investigate the effect of gp2 on N4 RNAPII activity. Gp2 did not activate transcription of double-stranded linear or supercoiled, promoter-containing templates (data not shown). Therefore, we tested the effect of gp2 on N4 RNAPII transcription on both the template and complementary strands of a middle promoter-containing N4 DNA fragment, from which a 107-nucleotide run-off transcript was expected (Abravaya and Rothman-Denes 1989b; Fig. 6A). However, gp2-stimulated transcription initiated at a number of sites under these conditions on both strands. Although the expected 107-nucleotide transcript was synthesized when the template strand was used, the major transcript (147 nucleotide) produced on this strand did not coincide with the previously identified in vivo start site on this fragment.

Figure 6.

(A) Gp2 activates N4 RNAPII transcription on single-stranded templates. In vitro transcription reactions contained 50nM of the 171-nucleotide template or complementary strands of the N4 Mc fragment, 40nM RNAPII, and increasing amounts of gp2. The positions of DNA molecular weight markers are indicated on the left. Asterisk denotes transcript initiating close to in vivo start site and arrows denote major transcripts. (B) Transcription initiates at the same sites in the absence or presence of gp2. S1 nuclease protection analysis of RNA products synthesized from the N4 Mc complementary strand. Template DNA was incubated in the absence or presence of 1.0μM gp2 and 40nM RNAPII for 10min. RNA products were isolated and hybridized to the end-labeled oligonucleotide MCC101-165. Only 12% of the RNA synthesized in the presence of gp2 was used, to allow comparison of the start sites. (Right lanes) Maxam-Gilbert sequencing reactions of the end-labeled probe. The positions of DNA molecular weight markers are indicated on the left. (C) Gp2 does not activate transcription at high RNAPII concentrations. Transcription reactions were carried out with the indicated amount of RNAPII and 50 nM MCC101-165 DNA in the absence or presence of 0.4 μM gp2. The positions of DNA molecular weight markers are indicated on the left.

The 5′ ends of RNAs transcribed from the complementary strand in the absence and presence of gp2 were compared using S1 nuclease protection and eightfold less RNA when synthesized in the presence of gp2 (Fig. 6B). Clusters of three major fragments, probably resulting from S1 nuclease invasion of the rU:dA base pairs at the end of the hybrid, were detected whether the RNAs were synthesized in the absence or presence of gp2. A similar result (data not shown) was obtained when the major transcript originating from the template strand was analyzed (data not shown). Therefore, gp2 did not affect RNAPII start-site selection on single-stranded templates.

Run-off transcription reactions were carried out at increasing concentrations of N4 RNAPII (Fig. 6C). In the absence of gp2, RNA synthesis increased with increasing RNAP concentrations, and longer products were detected. Gp2 addition inhibited the synthesis of longer products, although it promoted 3′ nontemplated addition. Moreover, Gp2 addition did not activate at the highest RNAP concentration, suggesting that gp2 activates transcription on single-stranded templates through N4 RNAPII recruitment.

To further analyze the interaction of N4 RNAPII and gp2, the ability of gp2 and RNAP to form complexes on single-stranded templates was tested by EMSA (Fig. 7A). In the absence of gp2, RNAP formed complexes inefficiently, and only at the highest concentration tested (Fig. 7A, lane 5, denoted by *). The formation of gp2/DNA complexes was dependent on gp2 concentration (Fig. 7A, cf. lanes 6 and 11). At both gp2 concentrations tested, an increase in complex formation was observed with increasing RNAP concentrations, although the mobility of the resulting complex did not change appreciably. In both cases, the extent of complex formation was higher than that observed with the individual proteins (Fig. 7A, cf. lanes 5,6 and 10, lanes 5,11 and 15). This effect could arise from cooperative binding through gp2-N4 RNAPII interactions, or if the binding of gp2 elicited a DNA conformational change that facilitates the binding of N4 RNAPII. This latter scenario does not necessarily imply protein-protein interactions or that gp2 must be present in the final complex. To analyze the composition of the complex, reactions containing hexahistidine-tagged N4 RNAPII and gp2 with or without DNA were subjected to gel electrophoresis. The native gel was electroblotted to nitrocellulose and probed with antibodies against gp2 or recombinant RNAPII (Fig. 7B). In the absence of ssDNA, a band migrating with lower mobility than free gp2 was detected using anti-gp2 antibodies when RNAPII is present (Fig. 7B, left panel, denoted by *). When antibodies against RNAPII were used, a band with slightly lower mobility than free RNAPII and comigrating with the band reacting with anti-gp2 antibodies was evident (Fig. 7B, right panel, denoted by *). These results indicate that gp2 comigrates with N4 RNAPII in the absence of ssDNA. In the presence of ssDNA, three species that react with both anti-gp2 and anti-RNAPII antibodies were detected. The reason for the difference in migration of these three species is unknown.

Figure 7.

Analysis of gp2-N4 RNAPII complex formation by gel retardation and Western blotting. (A) Increasing gp2 or RNAPII concentrations stimulates complex formation on single-stranded template. Reactions containing 50nM end-labeled MCC101-165 ssDNA, gp2, and RNAPII in transcription buffer were incubated for 15 min at 4°C. (B) Gp2 and RNAPII are present in a complex on ssDNA. Gp2, recombinant hexahistidine-tagged RNAPII, or a mixture of both proteins was incubated in the absence or presence of MCC101-165 ssDNA. Complexes were separated on native gels and probed with anti-gp2 antibody (left) or Xpress antibody (right). Asterix denotes RNAPII-gp2 complex formed in the absence of ssDNA. (C) Gp2 interacts with RNAPII. Recombinant hexahistidine-tagged RNAPII was incubated with gp2 and applied to a metal-affinity column.

To conclusively determine whether gp2 interacts with N4 RNAPII, purified gp2 and recombinant RNAPII (hexahistidine-tagged at the N terminus of the p7 subunit) were applied to a metal-affinity column (Fig. 7C). All input N4 RNAPII was retained on the column, although some gp2 was not. The column was washed with 1 M NaCl buffer; no p4 was detected in the wash, indicating that the interaction between the two RNAPII subunits is resistant to high-salt concentrations. P7, p4, and gp2 were detected in equimolar amounts in the 100-mM imidazole eluate. Similar results were obtained when the column was preloaded with RNAPII and excess gp2 was applied. In contrast, Eco SSB did not interact with N4 RNAPII and, conversely, gp2 did not interact with N4 vRNAP (data not shown). Therefore, gp2 binds specifically to RNAPII in the absence of ssDNA through an interaction that is resistant to 1 M NaCl concentration. Because gp2 binds to ssDNA as an oligomer, the stoichiometry of interaction suggests that the gp2 oligomer might dissociate upon interaction with N4 RNAPII. These results support our hypothesis that gp2 recruits N4 RNAPII to single-stranded templates through specific protein-protein interactions. The site(s) of gp2 interaction on N4 RNAPII remains to be identified.

Discussion

The activator of N4 RNAPII is a single-stranded DNA-binding protein

The involvement of gp2 in in vivo N4 middle RNA synthesis, its tight association with the DNA/inner membrane of infected cells (Zehring et al. 1983), and its ability to direct RNAPII-specific transcription in a semipurified system (Abravaya and Rothman-Denes 1989a) suggested that gp2 might specifically recognize N4 middle promoters either by itself or after interaction with RNAPII. Yet, characterization of the purified recombinant protein revealed that gp2 is a nonspecific single-stranded DNA-binding protein.

Gp2 displays the benchmark properties of single-stranded DNA-binding proteins (Chase and Williams 1986). Although it is difficult to assign gp2 to a particular class of single-stranded DNA-binding proteins due to the lack of sequence homology or structural information, gp2 shares several properties with other single-stranded DNA-binding proteins. The base preference of gp2 binding for pyrimidines (dT > dC » dA) has also been observed for T4 gp32 (Newport et al. 1981), Eco SSB (Overman et al. 1988), and the heterotrimeric human RPA (Kim et al. 1992). The gp2-binding site size was estimated to be 3-4 nucleotides per monomer. The Ff gene V family of SSBs displays similar binding stoichiometries (Kansy et al. 1986; Bulsink et al. 1988). M13 gene V protein binds as a dimer to form stable complexes on short oligonucleotides (Folkers et al. 1994). In contrast, gp2 requires at least 30nucleotides of DNA for association. Gp2 elutes as a 150-kD complex upon gel-filtration chromatography in 0.15 and 1 M NaCl, indicating oligomerization (R.H. Carter, unpubl.). Gp2/30-mer complexes migrate more slowly and are less stable than gp2/40-mer complexes, whereas complexes with longer oligonucleotides migrate with progressively lower mobility as expected from the increase in length of the DNA. An increase in mobility upon binding of Eco SSB and replication protein A (RPA) to longer oligonucleotides has been observed (Blackwell and Borowiec 1994; Mitas et al. 1997). RPA binds to 8-10nucleotides through two ssDNA-binding domains (DBD-A and DBD-B) of the RPA70subunit (Pfuetzner et al. 1997; Walther et al. 1999), to form an unstable complex (Blackwell and Borowiec 1994). In a second mode, in which 30nucleotides are occluded, a stable complex is formed through additional interactions of a third ssDNA-binding domain of RPA70(DBD-C) and the RPA32 DNA-binding domain with ssDNA (Kim et al. 1992; Bochkareva et al. 2001, 2002). We surmise that, in spite of a 3-4-nucleotide binding site size, the instability of gp2/20-mer complexes and the relative slow migration of gp2/30-mer complexes must reflect different modes of interaction between monomers in the oligomer and ssDNA. The oligomerization state of gp2 as well as its implications to single-stranded DNA binding is under investigation.

A model for N4 RNAPII promoter recognition

Phylogenetic analysis of T7-like RNA polymerases indicates the existence of three subfamilies, the phage (T7, T3, SP6, K11) polymerases, the nuclear-encoded mitochondrial and chloroplast polymerases, and the mitochondrial plasmid-encoded enzymes (Cermakian et al. 1997). Surprisingly, both bacteriophage N4-coded enzymes (vRNAP and N4 RNAPII) cluster with the plasmid-encoded polymerases (Kazmierczak et al. 2002). T7-like RNA polymerases contain four functionally important motifs, DxxGR, A, B, and C (Delarue et al. 1990). The T7 RNAP structure resembles a cupped hand with thumb and fingers subdomains rising on each side of a palm subdomain, where Motifs DxxGR, A, and C are located, whereas Motif B lies in the fingers subdomain (Jeruzalmi and Steitz 1998). Comparison of the sequences of N4 RNAPII subunits (p7/p4) with the T7 RNAP sequence indicates the presence within N4 RNAPII of the four motifs as well as other blocks of sequence similarity lying within the fingers, palm, and thumb subdomains (Willis et al. 2002). The DxxGR motif lies near the C terminus of the p7 subunit, whereas motifs A, B, and C are present in the p4 subunit. Promoter recognition by T7 RNA polymerase is achieved by insertion of the “specificity loop” (amino acids 739-770) into the DNA major groove (-8 to -12 bp) and of a flexible surface loop (amino acids 93-101) into the minor groove of an A + T rich sequence (-13 to -17 bp; Raskin et al. 1993; Rong et al. 1998; Cheetham and Steitz 2000). The N4 RNAPII p4 polypeptide contains a segment of unknown function whose position roughly corresponds to that of the T7 “specificity loop,” whereas the N4 RNAPII N-terminal domain is truncated by 156 amino acids relative to T7 RNAP, suggesting that the flexible surface loop is absent (Willis et al. 2002). N4 RNAPII is inactive on double-stranded templates containing in vivo sites of transcription initiation (Zehring and Rothman-Denes 1983). Although gp2 is essential in vivo for N4 middle transcription, it does not bind to promoter-containing, double-stranded templates or endows N4 RNAPII with the ability to initiate transcription at middle promoters. We have shown that (1) gp2 is a nonspecific single-stranded DNA-binding protein that stimulates N4 RNAPII transcription on single-stranded DNA, (2) gp2 and N4 RNAPII bind cooperatively to ssDNA, and (3) gp2 interacts with RNAPII to form a complex in which RNAPII and gp2 are present in equimolar amounts. We conclude that gp2 activates RNAPII transcription by recruiting the polymerase to single-stranded templates.

What is the role of N4 gp2 in promoter recognition by N4 RNAPII? N4 middle promoter-containing fragments were identified on the basis of their ability to direct transcription of downstream plasmid sequences after phage infection (Abravaya and Rothman-Denes 1989b). In vitro transcription from middle promoters present in supercoiled plasmids was observed upon addition of extracts from N4-infected cells, implying that plasmid-borne promoters are suitable templates for specific transcription (Abravaya and Rothman-Denes 1989a). However, in vivo expression of recombinant N4 RNAPII and gp2 did not support transcription from plasmid-borne middle promoters (R.H. Carter, unpubl.), indicating that an additional phage-coded factor is necessary for N4 middle transcription. On the basis of the properties of gp2, N4 RNAPII, and N4 middle promoters, we propose that a yet-unidentified N4-coded protein is responsible for site-specific DNA binding through interaction with the upstream conserved sequences of the promoter. We further propose that binding of this protein induces unwinding of a region downstream to its binding site. Such an activity is a hallmark of proteins involved in initiation of E. coli (dna A protein) and bacteriophage λ (λ O protein) DNA replication (for review, see Kornberg and Baker 1992). Unwinding would allow the site-specific recruitment of gp2 and concomitant or subsequent recruitment of RNAPII through interactions with gp2. Moreover, single strandedness between the conserved promoter elements that are present at a variable distance (12-20bp) would provide flexibility to allow recognition of the two conserved sequences (Tomonaga et al. 1998; Hammer et al. 2001).

Promoter recognition by T7-like RNA polymerases

Except for T7 RNA polymerase and the closely related phage T3, SP6, and K11 enzymes, all other members of the T7 RNAP-like family that have been characterized thus far require additional factors for transcription initiation. The catalytic cores of the yeast and human mitochondrial RNA polymerases are inactive on promoter-containing templates (Fisher and Clayton 1985; Kelly and Lehman 1986; Schinkel et al. 1987). Specific initiation by yeast mitochondrial RNAP requires a 39.5-kD transcription factor, Mtf1 (Winkley et al. 1985; Schinkel et al. 1987). Mtf1 cannot recognize promoter sequences on its own (Schinkel et al. 1988); however, it associates with the catalytic core (RPO 41) in solution, forming a holoenzyme complex that is competent for promoter recognition (Mangus et al. 1994). Human mitochondrial RNA polymerase, POLRMT (Tiranti et al. 1997), accurately transcribes templates containing the human mitochondrial promoters only when supplemented with the 24.4-kD high-mobility box protein TFAM (Fisher and Clayton 1985; Parisi and Clayton 1991) and either TFB1M or TFB2M transcription factors (Falkenberg et al. 2002). It has been suggested previously that yeast Mtf1 has similarities to bacterial σ factors (Jang and Jaehning 1991); surprisingly, the crystal structure reveals that it is structurally homologous to rRNA methyltransferase ErmC′ (Schubot et al. 2001). The human factors, TFB1M and TBF2M, have sequence similarity to bacterial rRNA dimethyltransferases, and each factor independently interacts stoichiometrically with POLRMT to form a heterodimer (Falkenberg et al. 2002). It has been suggested that the homology of mitochondrial transcription factors to bacterial rRNA methyltransferases might reflect their recruitment to the mitochondrial transcription apparatus through evolution (Schubot et al. 2001; Falkenberg et al. 2002). On the other hand, there is no evidence supporting a direct interaction between yeast Mtf1, human TBF1M, or TFB2M and promoter sequences. The existence of a region homologous to the T7 RNAP “specificity loop” in RPO41 led to the suggestion that determinants of promoter recognition reside in the catalytic core (Schadel and Clayton 1995). In this context, the transcription factors would bind to the catalytic core and induce a conformational change leading to interaction of the catalytic core with the promoter (Schubot et al. 2001).

In contrast to the mitochondrial enzymes, the bacteriophage N4-encoded RNA polymerases use single-stranded DNA-binding proteins for promoter recognition. Bacteriophage N4 virion RNAP, the most distantly related member of the T7-like RNAP family (Kazmierczak et al. 2002), is inactive on linear double-stranded templates, but transcribes denatured genomic N4 DNA or promoter-containing single-stranded DNAs with in vivo specificity (Falco et al. 1978; Haynes and Rothman-Denes 1985). E. coli single-stranded DNA-binding protein (Eco SSB) specifically activates N4 vRNAP transcription at N4 early promoters on supercoiled templates by providing the 5-7-bp stem, 3-nucleotide loop DNA hairpin structure required for promoter recognition (Haynes and Rothman-Denes 1985; Glucksmann et al. 1992; Markiewicz et al. 1992). In addition, Eco SSB binds to the RNA transcript as it exits from the enzyme, preventing formation of a persistent RNA:DNA hybrid, and therefore, allowing template recycling (Davydova and Rothman-Denes 2003). We expect that further analysis of transcription initiation by N4 RNAPII will provide insights into the mechanism of promoter recognition by mitochondrial RNA polymerases and the role of single-stranded DNA-binding proteins in transcription activation (Rothman-Denes et al. 1998).

Materials and methods

Bacterial strains and plasmids

E. coli strain W3350(DE3)/pLysS was used for phage infections (Choi et al. 1995). E. coli strain BL21(DE3)/pLysS was used for gp2 overproduction. ORF2 was PCR-amplified from N4 genomic DNA using primers (5′-GCCGAATTCATATGGCTAT CACTACTTTTGC-3′; 5′-GGGGATCCTTAGAAAGTCAGTTT ACGAGC-3′) that introduce NdeI and BamHI restriction enzyme sites. These were used to clone the amplicon into plasmid pET11a (Novagen) to create expression plasmid pSH2. The resulting recombinant protein does not contain any vector-encoded sequences.

DNA templates

The N4 Mc fragment was isolated from pBR[Mc] (Malone et al. 1988) and cloned into the BamHI site of M13mp7. BamH1 digestion of the single-stranded viral M13 DNA containing the fragment inserted in either orientation released the 171 base-long template or complementary strands of the Mc fragment, which were used as templates in transcription reactions. Template MCC101-165 (65 mer), which was used for S1 mapping and gel-retardation assays, corresponds to the sequence of the complementary strand of the Mc fragment from positions 101 to 165. Deoxyoligonucleotides were purchased from Integrated DNA Technologies, gel purified, and quantitated by UV absorbance.

Measurement of in vivo N4 DNA synthesis and labeling of proteins after induction or phage infection

E. coli strain W3350(DE3)/pLysS/pSH2 was infected with N4 phage and DNA synthesis was measured (Guinta et al. 1986). To induce ORF2 expression, cells were treated with 2 mM isopropyl-β-D-galactoside (IPTG) 15 min prior to phage addition. Proteins were labeled as described (Willis et al. 2002).

Purification of gp2 from the T7-based expression system

Gp2 activity was measured by supplementation of fractions with RNAPII (Abravaya and Rothman-Denes 1989a). BL21(DE3)/pLysS/pSH2 cells were grown in M9 medium (Miller 1972) containing ampicillin (100 μg/mL) and chloramphenicol (25 μg/mL). When the culture reached OD600 = 0.05, IPTG was added to 400 μM, and 3 h later, cells were harvested by centrifugation. Lysis and preparation of the DNA/membrane complex was performed as described (Zehring and Rothman-Denes 1983) with the following modifications. The DNA/membrane pellet was resuspended in 150mM NaCl A-10Buffer [10mM MgCl2, 1 mM EDTA, 10% glycerol, 10 mM Tris-HCl at pH 7.9 (4°C), 1 mM dithiothreitrol (DTT), 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride] by repeated passage through 18- and 23-gauge needles. The sheared DNA/membrane complex was collected by centrifugation and resuspended in 150mM NaCl A-10buffer. DNaseI was added to 5 U/mL final concentration, and the mixture was incubated for 20min at 37°C. After centrifugation, gp2 was recovered in the supernatant. Proteins precipitating between 25% and 50% ammonium sulfate were resuspended in 150mM NaCl-BTP buffer (20mM bis-Tris propane-HCl at pH 7.0, 10% glycerol, 1 mM DTT) and applied onto a Sephacryl S-300 HR(26/60) (Pharmacia LKB) column equilibrated with the same buffer. Column fractions were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and assayed for nuclease activity. Gp2-containing fractions were pooled and applied onto a Macro-Prep Ceramic Hydroxyapatite (Bio-Rad) column equilibrated with 150mM NaCl-BTP buffer. After washing with the same buffer, gp2 was step eluted with PS Buffer (100 mM NaPO4 at pH 7.0, 10% glycerol, 1mM DTT) in BTP. Gp2 eluted between 15 and 35 mM NaPO4 with trace amounts of contaminating nuclease activity. The eluate was loaded onto a Q-Sepharose (Pharmacia LKB) column equilibrated with 100 mM NaCl-BTP buffer. Gp2 was eluted with a linear gradient of 100-500 mM NaCl in BPT and was nuclease free. Pooled fractions were concentrated using Centricon-30 (Amicon) and dialyzed against 20mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM DTT, 50% glycerol. Aliquots were stored at -80°C.

Column fractions were assayed for nuclease activity by following the conversion of supercoiled pUC19 plasmid to the nicked form. Reaction mixtures (5 μL) containing 2 μL of DNaseI reaction mix (0.1 μg pUC19 supercoiled plasmid, 125 mM Tris-HCl at pH 7.5, 25 mM MgCl2, 0.25 mM EDTA, 75 μg/mL BSA, 1.25 mM DTT) and 3 μL of protein fraction were incubated for 1.5 h at 37°C, quenched by addition of 1 μL load buffer (12% Ficoll, 60mM EDTA, 1% SDS) and analyzed on a 1% agarose gel.

Cloning and purification of N4 RNAPII containing an N-terminal hexahistidine tag in the p7 subunit

A DNA fragment encompassing ORF15 (p7) and ORF16 (p4; Willis et al. 2002) was generated by PCR amplification using N4 genomic DNA as template and Pfu DNA polymerase (Strata-gene) as per manufacturer's recommendations. (Primers: 5′-GCTCTCGAGATCTACTATCGAACATCAGA-3′; 5′-GCAC TGCAGTTAAGATAGAGCGTATTCGGT-3′). The PCR primers introduced XhoI and PstI restriction sites at the 5′ end of ORF15 and the 3′ end of ORF16, respectively. The PCR product was cut with the appropriate enzymes and cloned into the expression plasmid pBAD/HisB (Invitrogen), digested previously with PstI and XhoI, to generate pAD1. The recombinant p7 subunit contains a 48 amino acid vector-encoded terminal leader sequence (MGGSHHHHHHGMASMTGGQQMGRDLY DDDDKDPSSRSAAGTIWEFEAW), which includes the hexahistidine tag and the Xpress epitope (underlined), and lacks the N-terminal methionine of p7. Induction of recombinant RNAPII expression complemented N4 phage am15/am23, which contains mutations in ORFs 15 and 16 (Willis et al. 2002).

E. coli BL21 cells bearing pAD1 were grown at 37°C to OD600 = 0.5 in Lenox L Broth (LB) medium containing 100 μg/mL ampicillin. After centrifugation, cell pellets were resuspended in LB medium containing 0.2% arabinose and grown 1 h at 37°C. After low-speed centrifugation, pelleted cells were resuspended in sonication buffer [20mM Tris-HCl at pH 8.0, 20 mM NaCl, 1× Complete protease inhibitor, EDTA-free (Roche)] and sonicated in pulses on ice. After low-speed centrifugation, the cleared lysate was applied to a Talon Co2+-IMAC resin column (Clontech) equilibrated in sonication buffer. The column was washed with 20mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 1 M NaCl, followed by cold sonication buffer. Protein was eluted with 20mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 20 mM NaCl, 100 mM imidazole and concentrated on HiTrap Q (Amersham-Pharmacia). Protein fractions were pooled and applied to a Macro-Prep Ceramic Hydroxyapatite (Bio-Rad) column equilibrated with 20mM sodium phosphate (pH 7.3) buffer, and eluted with a 20-800 mM sodium phosphate (pH 7.3) linear gradient. Eluted protein was diluted 1:1 (v/v) in glycerol and stored at -20°C. The purified recombinant enzyme was as active as endogenous N4 RNAPII (Zehring and Rothman-Denes 1983) and was activated by gp2.

EMSA

ssDNAs were end-labeled with T4 polynucleotide kinase (New England Biolabs) and [γ32P]ATP (3000 Ci/mmole, Amersham). Conditions for assays are specified in the figure legends. Samples (10μL) contained 300μg/mL BSA and 10%-15% glycerol, and were analyzed on 5%-9% polyacrylamide (80:1, acrylamide to bisacrylamide), 2.5% glycerol, 1× gel shift running buffer (380mM glycine, 2 mM EDTA, 50mM Tris-HCl at pH 8.5). Cesium chloride-banded pBR[Mc] was used as the dsDNA competitor. Cesium chloride-pelleted RNA isolated from rifampicin-pretreated, W3350cells infected with wild-type N4 phage was used as the RNA competitor and was denatured by boiling immediately prior to use. M13mp18 viral DNA was used as the ssDNA competitor.

Gp2 fluorescence spectra and titrations

Fluorescence measurements were made in an Alphascan (Photon Technologies Inc.) fluorimeter at 22°C. Experiments were performed in 20mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 1 mM EDTA, and NaCl as indicated in the figure legends. Fluorescence excitation was performed at 292 nm. Fluorescence intensity was detected at a right angle from the incident excitation from 300 to 400 nm in 0.5-nm increments with 0.25-sec integration time. Each data point in titration experiments corresponds to the fluorescence intensity at 340nm, the maximal value for gp2. Nucleic acids were added incrementally, and the reaction mixtures were allowed to equilibrate with stirring for 10min at 22°C. Values were obtained by averaging three independent scans and subtracting the average of three blank scans. The 340-nm fluorescence (F) at each point in titration experiments was plotted as quenching (1-F/F0), in which F0 is the value for the initial fluorescence of the gp2 solution. The quenching data were fitted to the equation y = [m1 * m0/(m2 + m0)] + m3, in which m0= quenching, m1 = maximum quenching, m2 = Kd, and m3 = minimum quenching.

In vitro transcription with purified N4 RNAPII and gp2

Transcription reactions (5-15 μL) contained 10mM MgCl2, 0.1 mM EDTA, 1 mM each ATP, CTP, GTP, 0.1 mM UTP [α-32P]UTP (25 Ci/mmole, Amersham), 100μg/mL BSA, 20mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0) and template, RNAPII and gp2 concentrations as indicated in figure legends. Reactions were preincubated at 37°C for 5 min and initiated upon the addition of the four rNTPs. After 2 min of incubation at 37°C, the reactions were terminated by adding 1.5 volumes stop buffer (95% formamide, 1 mM EDTA) and analyzed on 8% or 10% acrylamide/8 M urea gels. RNAPII was purified as described previously (Willis et al. 2002).

S1 nuclease protection

An end-labeled oligonucleotide spanning positions 101-165 of the complementary strand, from which all observed full-length run-off transcripts (all shorter than 140nt) originate, was used as a probe. S1 nuclease protection and analysis was performed as described (Ausubel et al. 1999).

Detection of gp2-N4 RNAPII interactions on native gels

Reaction mixtures (15 μL) containing the specified combinations of 85 pmole gp2, 16 pmole hexahistidine-tagged N4 RNAPII, 20pmole MCC101-165 ssDNA in 10mM MgCl2, 0.1 mM EDTA, 20mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0) were incubated at 25°C for 25 min before loading onto a 6% polyacrylamide gel (40:0.6 acrylamide to bis-acrylamide). Electrophoresis was performed at 4°C in 50mM Tris-acetate (pH 8), 2 mM EDTA.

Electrotransfer of proteins to nitrocellulose membranes (NitroPure, Micron Separations, Inc) was performed using 1× transfer buffer (25 mM Tris, 192 mM Glycine at pH 8.3). Anti-gp2 rabbit antibodies were affinity purified from serum by overnight adsorption to and subsequent elution from nitrocellulose containing gp2 protein. Western analysis of gp2 was performed using the SuperSignal (Pierce Chemical) blotting kit according to the manufacturer's instructions. Anti-gp2 antibodies were stripped from the membrane by incubation in 100 mM 2-β-mercaptoethanol, 2% SDS, 62.5 mM Tris-HCl (pH 6.8) at 70°C for 30min, and RNAPII was detected using Anti-Xpress antibody (Invitrogen) according to the supplier's specifications.

Detection of gp2-N4 RNAPII interactions on metal-chelating column

Hexahistidine-tagged RNAPII (100 pmole) and gp2 (300 pmole) in 20mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 100mM NaCl (150μL total volume) were loaded onto a 50-μL Talon Co2+-IMAC resin column. The column was washed with 1.5 mL of the same buffer, followed by 100μL of 20mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 1 M NaCl. Bound proteins were eluted with 150μL of 20mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 100 mM NaCl, and 100 mM imidazole. Gp2 was not retained by the column in the absence of N4 RNAP II. Proteins were analyzed on 15% SDS-PAGE followed by silver staining.

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. A. Bochkarev, E. Davydova, E.P. Geiduschek, and S. Kowalczykowski for critical comments. S.H.W. performed some of the work described in this manuscript while at the laboratory of F. Stahl (University of Oregon). We thank him for his hospitality. This work was supported by NIH grant AI 12575 to L.B.R.-D. R.H.C. was supported partially by NIH grant T32 GM 07183.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by payment of page charges. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

Article and publication are at http://www.genesdev.org/cgi/doi/10.1101/gad.1121403.

References

- Abravaya K. and Rothman-Denes, L.B. 1989a. In vitro requirements for N4 RNA polymerase II-specific initiation. J. Biol. Chem. 264: 12695-12699. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ____. 1989b. N4 RNA polymerase II sites of transcription initiation. J. Mol. Biol. 211: 359-372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ausubel F.M., Brent, R., Kingston, R.E., Moore, D.D., Seidman, J.G., Smith, J.A., and Struhl, K. (eds.) 1999. Current protocols in molecular biology. Wiley, New York, N.Y.

- Blackwell L. and Borowiec, J. 1994. Human replication protein A binds single-stranded DNA in two distinct complexes. Mol. Cell. Biol. 14: 3993-4001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bochkareva E., Belegu, V., Korolev, S., and Bochkarev, A. 2001. Structure of the major single-stranded DNA-binding domain of replication protein A suggests a dynamic mechanism for DNA binding. EMBO J. 20: 612-618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bochkareva E., Korolev, S., Lees-Miller, S.P., and Bochkarev, A. 2002. Structure of the RPA trimerization core and its role in the multistep binding mechanism of RPA. EMBO J. 21: 1855-1863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bulsink H., Harmsen, B., and Hilbers, C. 1988. DNA-binding properties of gene-5 protein encoded by bacteriophage M13. 2. Further characterization of the different binding modes for poly- and oligodeoxynucleic acids. Eur. J. Biochem. 176: 597-608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carey J. 1991. Gel retardation. Methods Enzymol. 208: 103-117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cermakian N., Ikeda, T.M., Miramontes, P., Lang, B.F., Gray, M.W., and Cedergren, R. 1997. On the evolution of the single-subunit RNA polymerases. J. Mol. Evol. 45: 671-681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chase J.W. and Williams, K.R. 1986. Single-stranded DNA binding proteins required for DNA replication. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 55: 130-136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheetham G.M.T. and Steitz, T.A. 2000. Insights into transcription: Structure and function of single-subunit DNA-dependent RNA polymerases. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 10: 117-123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho N.Y., Choi, M., and Rothman-Denes, L.B. 1995. The bacteriophage N4 single-stranded DNA binding protein (N4SSB) is the transcriptional activator of E. coli RNA polymerase at N4 late promoters. J. Mol. Biol. 246: 461-471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi M., Miller, A., Cho, N-Y., and Rothman-Denes, L.B. 1995. Identification, cloning and characterization of the bacteriophage N4 gene encoding the single-stranded DNA binding protein; a protein required for phage replication, recombination and late transcription. J. Biol. Chem. 270: 22541-22547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davydova E.K. and Rothman-Denes, L.B. 2003. E. coli single-stranded DNA binding protein mediates template recycling during transcription by bacteriophage N4 virion RNA polymerase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 100: 9250-9255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delarue M., Poch, O., Tordo, N., Moras, D., and Argos, P. 1990. An attempt to unify the structure of polymerases. Protein Eng. 3: 461-467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falco S.C. and Rothman-Denes, L.B. 1979a. Bacteriophage N4-induced transcribing activities in Escherichia coli. I. Detection and characterization in cell extracts. Virology 95: 454-465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ____. 1979b. Bacteriophage N4-induced transcribing activities in Escherichia coli. II. Association of the N4 transcriptional apparatus with the cytoplasmic membrane. Virology 95: 466-475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falco S.C., VanderLaan, K., and Rothman-Denes, L.B. 1977. Virion-associated RNA polymerase required for bacteriophage N4 development. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. 74: 520-523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falco S.C., Zivin, R., and Rothman-Denes, L.B. 1978. Novel template requirements of N4 virion RNA polymerase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 75: 3220-3224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falkenberg M., Gaspari, M., Rantanen, A., Trifunovic, A., Larson, N.-G., and Gustafsson, C.M. 2002. Mitochondrial transcription factors B1 and B2 activate transcription of human mtDNA. Nat. Genet. 31: 289-294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher R.P. and Clayton, D.A. 1985. A transcription factor required for promoter recognition by human mitochondrial RNA polymerase. J. Biol. Chem. 260: 11330-11338. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folkers P.J.M., van Duyhoven, J.P.M., Harmsen, B.J.M., Konings, R.N.H., and Hilbers, C.W. 1994. The solution structure of the Tyr41 → His mutant of the single-stranded DNA binding protein encoded by gene V of filamentous bacteriophage M13. J. Mol. Biol. 236: 229-246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glucksmann M.A., Markiewicz, P., Malone, C., and Rothman-Denes, L.B. 1992. Specific sequences and a hairpin structure in the template strand are required for N4 virion RNA polymerase promoter recognition. Cell 70: 491-500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glucksmann-Kuis M.A., Dai, X., Markiewicz, P., and Rothman-Denes, L.B. 1996. Eco SSB activates N4 virion RNA polymerase promoters by stabilizing a DNA hairpin required for promoter recognition. Cell 84: 147-154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guinta D., Stambouly, J., Falco, S.C., Rist, J.K., and Rothman-Denes, L.B. 1986. Host and phage-coded functions required for coliphage N4 DNA replication. Virology 150: 33-44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammer T., Wu, M., and Schleif, R. 2001. The role of DNA rigidity in DNA looping-unlooping by AraC. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 98: 177-181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haynes L.L. and Rothman-Denes, L.B. 1985. N4 virion RNA polymerase sites of transcription initiation. Cell 41: 597-605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jang S.H. and Jaehning, J.A. 1991. The yeast mitochondrial RNA polymerase specificity factor, MTF1, is similar to bacterial σ factors. J. Biol. Chem. 266: 22671-22677. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeruzalmi D. and Steitz, T.A. 1998. Structure of T7 RNA polymerase complexed to the transcriptional inhibitor T7 lysozyme. EMBO J. 17: 4101-4113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kansy J., Clack, B., and Gray, D. 1986. The binding of fd gene 5 protein to polydeoxynucleotides: Evidence from CD measurements for two binding modes. J Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 3: 1079-1110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kazmierczak K.M., Davydova, E.K., Mustaev, A.A., and Rothman-Denes, L.B. 2002. The phage N4 virion RNA polymerase catalytic domain is related to the single-subunit RNA polymerases. EMBO J. 21: 5815-5823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly J.L. and Lehman, I.R. 1986. Yeast mitochondrial RNA polymerase. Purification and properties of the catalytic subunit. J. Biol. Chem. 261: 10340-10347. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim C., Snyder, R.O., and Wold, M.S. 1992. Binding properties of replication protein A from human and yeast cells. Mol. Cell. Biol. 12: 3050-3059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kornberg A. and Baker, T. 1992. DNA replication. Freeman, New York.

- Lakowicz J.R. 1983. Principles of fluorescence spectroscopy. Plenum Press, New York.

- Lohman T.M. and Mascotti, D.P. 1992. Thermodynamics of ligand-nucleic acid interactions. Methods Enzymol. 212: 400-424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lohman T.M. and Overman, L.B. 1985. Two binding modes in Escherichia coli single strand binding protein-single stranded DNA complexes. Modulation by NaCl concentration. J. Biol. Chem. 260: 3594-3603. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malone C., Spellman, S., Hyman, D., and Rothman-Denes, L.B. 1988. Cloning and generation of a genetic map of bacteriophage N4 DNA. Virology 162: 328-336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mangus D.A., Jang, S.H., and Jaehning, J.A. 1994. Release of the yeast mitochondrial RNA polymerase specificity factor from transcription complexes. J. Biol. Chem. 269: 26568-26574. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markiewicz P., Malone, C., Chase, J.W., and Rothman-Denes, L.B. 1992. Escherichia coli single-stranded DNA binding protein is a supercoiled-template dependent transcriptional activator of N4 virion RNA polymerase. Genes & Dev. 6: 2010-2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller A.A., Wood, D., Ebright, R.E., and Rothman-Denes, L.B. 1997. RNA polymerase β′ subunit: A target of DNA binding-independent activation. Science 275: 1655-1657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller J.H. 1972. Experiments in molecular genetics. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY.

- Mitas M., Chock, J., and Christy, M. 1997. The binding-site sizes of Escherichia coli single-stranded-DNA-binding protein and mammalian replication protein A are 65 and ≥ 54 nucleotides respectively. Biochem J. 324: 957-961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newport J.W., Lonberg, N., Kowalczykowski, S.C., and von Hippel, P. 1981. Interactions of bacteriophage T4-coded gene 32 protein with nucleic acids. J. Mol. Biol. 145: 105-121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Overman L.B., Bujalowski, W., and Lohman, T.M. 1988. Equilibrium binding of E. coli single-stranded binding protein to single-stranded nucleic acids in the (SSB) 65 binding mode: Cation and anion effects and polynucleotide specificity. Biochemistry 27: 456-471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parisi MA. and Clayton, D.A. 1991. Similarity of human mitochondrial transcription factor 1 to high mobility group proteins. Science 252: 965-969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfuetzner R., Bochkarev, A., Frappier, L., and Edwards, A. 1997. Replication protein A. Characterization and crystallization of the DNA binding domain. J. Biol. Chem. 272: 430-434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raskin C.A., Diaz, G.A., and McAllister, W.T. 1993. T7 RNA polymerase mutants with altered promoter specificities. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 90: 3147-3151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rong M., He, B., McAllister, W.T., and Durbin, R.D. 1998. Promoter specificity determinants of T7 RNA polymerase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 95: 515-519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothman-Denes L.B., Dai, X., Davydova, E., Carter, R., and Kazmierczak, K.M. 1998. Transcriptional regulation by DNA structural transitions and single-stranded DNA-binding proteins. Cold Spring Harb. Symp. Quant. Biol. 63: 63-73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schinkel A.H., Groot Koerkamp, M.J.A., Touw, E.P.W., and Tabak, H.F. 1987. Specificity factor of yeast mitochondrial RNA polymerase. J. Biol. Chem. 262: 12785-12791. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schinkel A.H., Groot Koerkamp, M.J.A., and Tabak, H.F. 1988. Mitochondrial RNA polymerase of Saccharomyces cerevisiae: Composition and mechanism of promoter recognition. EMBO J. 7: 3255-3262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schubot F.D., Chen, C.-J., Rose, J.P., Dailey, T.A., Dailey, H.A., and Wang, B-C. 2001. Crystal structure of the transcription factor sc-mtTFB offers insights into mitochondrial transcription. Protein Sci. 10: 1980-1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shadel G.S. and Clayton, D.A. 1995. A Saccharomyces cerevisiae mitochondrial transcription factor, sc-mtTFB, shares features with σ-factors but is functionally distinct. Mol. Cell. Biol. 15: 2101-2108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tiranti V., Savoia, A., Forti, F., D'Apolito, M.F., Centra, M., Rocchi, M., and Zeviani, M. 1997. Identification of the gene encoding the human mitochondrial RNA polymerase (hmtRPOL) by cyberscreening of the Expressed Sequence Tags database. Hum. Mol. Genet. 6: 615-625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomonaga T., Michelotti, G.A., Libutti, D., Uy, A., Sauer, B., and Levens, D. 1998. Unrestraining genetic processes with a protein DNA hinge. Mol. Cell 1: 759-764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walther A.P., Gomes, X.V., Lao, Y., Lee, C.G., and Wold, M.S. 1999. Replication protein A interactions with DNA. 1. Functions of the DNA-binding and zinc-finger domains of the 70-kDa subunit. Biochemistry 38: 3963-3973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willis S.H., Kazmierczak, K.M., Carter, R.H., and Rothman-Denes, L.B. 2002. N4 RNA polymerase II, a heterodimeric RNA polymerase with homology to the single-subunit family of RNA polymerases. J. Bacteriol. 184: 4952-4961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winkley C.S., Keller, M.J., and Jaehning, J.A. 1985. A multi-component mitochondrial RNA polymerase from Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J. Biol. Chem. 260: 14214-14223. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zehring W.A. and Rothman-Denes, L.B. 1983. Purification and characterization of coliphage N4 RNA polymerase II activity from infected cell extracts. J. Biol. Chem. 258: 8074-8080. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zehring W.A., Falco, S.C., Malone, C., and Rothman-Denes, L.B. 1983. Bacteriophage N4-induced transcribing activities in E. coli. III. A third cistron required for N4 RNA polymerase II activity. Virology 126: 678-687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zivin R., Zehring, W., and Rothman-Denes, L.B. 1981. Transcriptional map of bacteriophage N4. Location and polarity of N4 RNAs. J. Mol. Biol. 152: 335-356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]