Abstract

Carbohydrates of all classes consist of glycoform mixtures built on common core units. Determination of compositions and structures of such mixtures relies heavily on tandem mass spectrometric data. Analysis of native glycans is often necessary for samples available in very low quantities and for sulfated glycan classes. Negative tandem mass spectrometry (MS) provides useful product ion profiles for neutral oligosaccharides and is preferred for acidic classes. In previous work from this laboratory, site-specific influences of sialylation on product ion profiles in the negative mode were elucidated. The present results show how the interplay of two other acidic groups, uronic acids and sulfates, determines product ion patterns for chondroitin sulfate oligosaccharides. Unsulfated chondroitin oligosaccharides dissociate to form C-type ions almost exclusively. Chondroitin sulfate oligosaccharides produce abundant B- and Y-type ions from glycosidic bond cleavage with C- and Z-types in low abundances. These observations are explained in terms of competing proton transfer reactions that occur during the collisional heating process. Mechanisms for product ion formation are proposed based on tandem mass spectra and the abundances of product ions as a function of collision energy.

Introduction

The development of tandem mass spectrometric methods for glycomics requires clear understanding of glycan fragmentation mechanisms. Released glycans are heterogeneous with regard to presence of acidic residues or modifying groups. Such acidic moieties strongly influence the energetics of fragmentation and the patterns of tandem mass spectrometric product ion formation. Glycosaminoglycans (GAGs) consist of repeating disaccharide units, several classes of which are sulfated. Oligosaccharides of composition (Gal6Xβ4GlcNAc6Sβ3)n where X = H or SO3H and S = SO3H (derived from keratan sulfate), dissociate for form abundant A-type cross-ring cleavages to the reducing terminal residue [1, 2]. Oligosaccharides of composition Δ(HexAβ3GalNAc4/6S)n (derived from chondroitin sulfate, CS) produce B- and Y-type ions [3–7], the pattern of which depends on the charge state [8]. Those of composition Δ(HexA2Xα/β4GlcNY6Z)n where X, Z = H or SO3H and Y = Ac, H, or SO3H (derived from heparan sulfate) produce a complex mixture of A-, B-, C-, X-, Y- and Z-type product ions [9–12]. The goal of this work is to describe mechanisms behind the formation of negative product ions for GAG oligosaccharides.

Non-sulfated native glycans dissociate in the positive mode to form abundant ions via glycosidic cleavages of the B- and Y-types, resulting from association of a cation with the glycosidic oxygen atom [13–15]. The most facile cross-ring cleavages are those to 4- or 6-linked reducing terminal residues [16–18]. Although cross-ring cleavage ions are abundant for 4-linked reducing terminal residues, those within internal branching residues have significantly lower abundances [19, 20]. Sialic acids and sulfate groups are eliminated readily in the positive mode, resulting in the loss of information [21]. In the negative mode, neutral glycans produce abundant C-type ions and cross-ring cleavages are observed within reducing terminal residues and to internal 4-linked residues [22–26]. 3-linked residues undergo double C/Z (D-type) cleavage, providing useful information on glycan structure [23]. Sialic acid groups, when present, dramatically increase the energy required for precursor ion dissociation in the negative mode and decrease the abundances of A- and D-type ions [27].

Negative ions generated from CS oligosaccharides fragment to form B- and Y-type ions [4, 8], in contrast to the C- and Z-type ions observed for deprotonated neutral carbohydrates. In this regard, the types of glycosidic bond cleavages observed are similar to those for cationized oligosaccharides in the positive mode [28–31]. CS oligosaccharides contain 3-linked reducing end GalNAc residues and do not form A-type cross-ring cleavage ions as primary fragments. These oligosaccharide ions undergo 0,2X-type cleavage to the non-reducing Δ-unsaturated uronosyl ring through a relatively facile retro-Diels-Alder mechanism [32].

This brief literature summary demonstrates that negatively charged oligosaccharide ions fragment differently depending on the presence or absence of acidic groups. Effective use of tandem mass spectrometric data to determine detailed structural information depends on understanding the mechanisms by which of acidic groups influence the pattern of product ions formed. This study examines the roles of mobile protons in oligosaccharide negative mode tandem mass spectrometric fragmentation pathways. The influence of NeuAc residues in the product ion patterns for milk and N-linked oligosaccharides have been described recently [27]. The roles of uronic acids in product ion patterns of CS glycosaminoglycan oligosaccharides will be examined here. The results are rationalized in terms of the energetic nature of the ions created during the electrospray process and in terms of the role of acidic protons in glycosidic bond cleavages. Practical implications for the design of tandem mass spectrometric platforms for comparative glycomics are discussed.

Experimental methods

CS type A, chondroitin, and chondroitinase enzymes were obtained from Seikagaku/Associates of Cape Cod (Falmouth MA). Testicular hyaluronidase (bovine) was obtained from Worthington Enzymes (Lakewood, NJ). CS 4,5-unsaturated disaccharides ΔHexAβ3GalNAc4S (ΔDi4S) and ΔHexAβ3GalNAc6S (ΔDi6S) were purchased from Seikagaku/Associates of Cape Cod. CS saturated disaccharide GlcAβ3GalNAc4S (Di4S) was purchased from V-Labs, Inc. (Covington, LA).

Enzymatic digestions

ΔHexAβ3GalNAc4Sβ4GlcAβ3GalNAc4S (ΔDi4SDi4S) was prepared by depolymerization of CS type A using chondroitinase ACI. ΔHexAβ3GalNAcβ4GlcAβ3GalNAc (ΔDiOSDiOS) was prepared by depolymerization of chondroitin with chondroitinase ACI. CS or chondroitin (100 μg) was digested with chondroitinase ACI (5 mU) in tris-HCl buffer (75 mM, pH 7.4) containing ammonium acetate (25 mM) for 5 min at 37 °C. The mixture was boiled for 1 min and then fractionated using a Superdex Peptide 3.2/30 column (Amersham Biosciences, Piscataway, NJ) using the mobile phase 0.1 M ammonium acetate, 10% acetonitrile at a flow rate of 100 μL/min. Collected fractions were dried in vacuo. GlcAβ3GalNAc4Sβ4GlcAβ3GalNAc4S (Di4SDi4S) was prepared by depolymerization of CS type A using testicular hyaluronidase. CS (100 μg) was digested with testicular hyaluronidase (2 μg) in tris-HCl buffer (75 mM, pH 7.4) for 36 hr at 37°C and separated using the Superdex Peptide column as above.

Methyl esterification

Dry samples were dissolved in 0.5 M methanolic HCl from freshly opened ampoules (Sigma Chemical Company, St. Louis, MO) and the solutions were kept at ambient temperature for 30 min before drying in vacuo. Samples were dissolved in 30% methanol and analyzed directly using negative ion nano-electrospray MS. Tandem mass spectra of disaccharide products (Figures 1 and 2) were consistent with the formation of methyl esterified methylglycosides. Tandem mass spectra of tetrasaccharide products (Figures 3–5) were consistent with formation of molecules with two methyl esterified uronic acid residues and unmodified reducing ends.

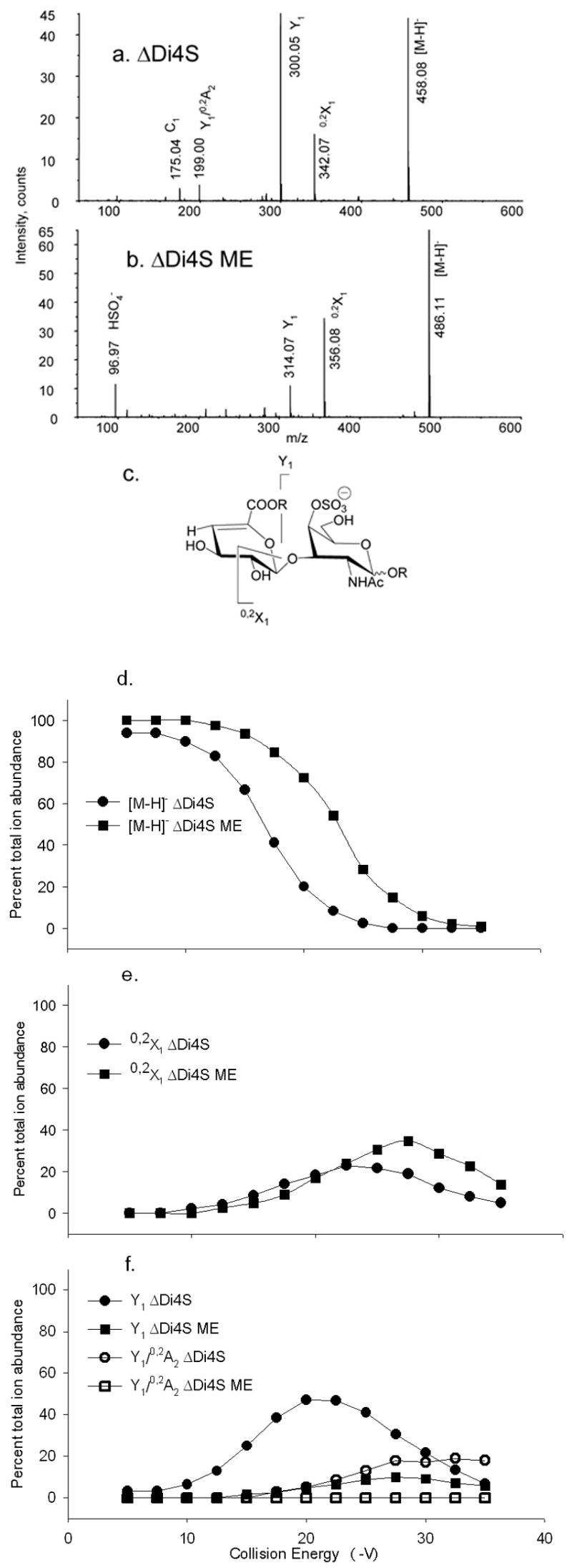

Figure 1.

Tandem mass spectra of (a) ΔDi4S, CE −17.5 V; (b) ΔDi4S ME, CE −22.5 V. Trends in product ion formation are shown in (c). The product ions above the structures are abundant for native forms and those below for derivatized forms. R = H for ΔDi4S and R = CH3 for ΔDi4S ME. CID breakdown diagrams for (d) [M–H]− ΔDi4S (●) and [M–H]− ΔDi4SME (■); (e)0,2X1 ΔDi4S (●) and 0,2X1 ΔDi4S ME (■), (f) Y1 ΔDi4S (●) and Y1 ΔDi4S ME (■); Y1/0,2A2 ΔDi4S (○), and Y1/0,2A2 ΔDi4S ME (□).

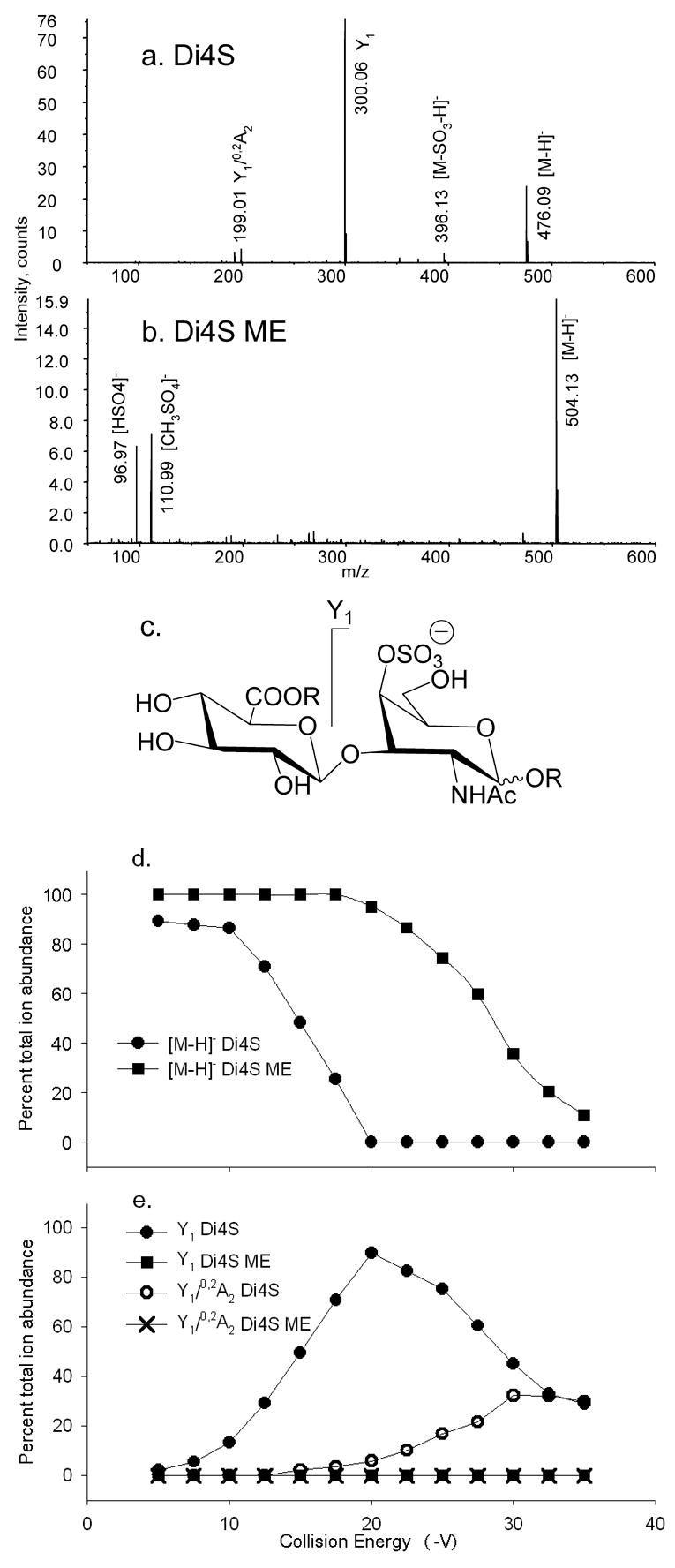

Figure 2.

Tandem mass spectra of (a) Di4S, CE −17.5 V and (b) Di4S ME, CE −27.5 V. Trends in product ion formation are shown in (c). The product ions above the structures are abundant for native forms and those below for derivatized forms. R = H for Di4S and R = CH3 for Di4S ME. CID breakdown diagrams for (d) [M–H]− Di4S (●) and [M–H]− Di4S ME (■); (e) Y1 Di4S (●) and Y1 Di4S ME (■), Y1/0,2A2 Di4S (○), and Y1/0,2A2 Di4S ME (×).

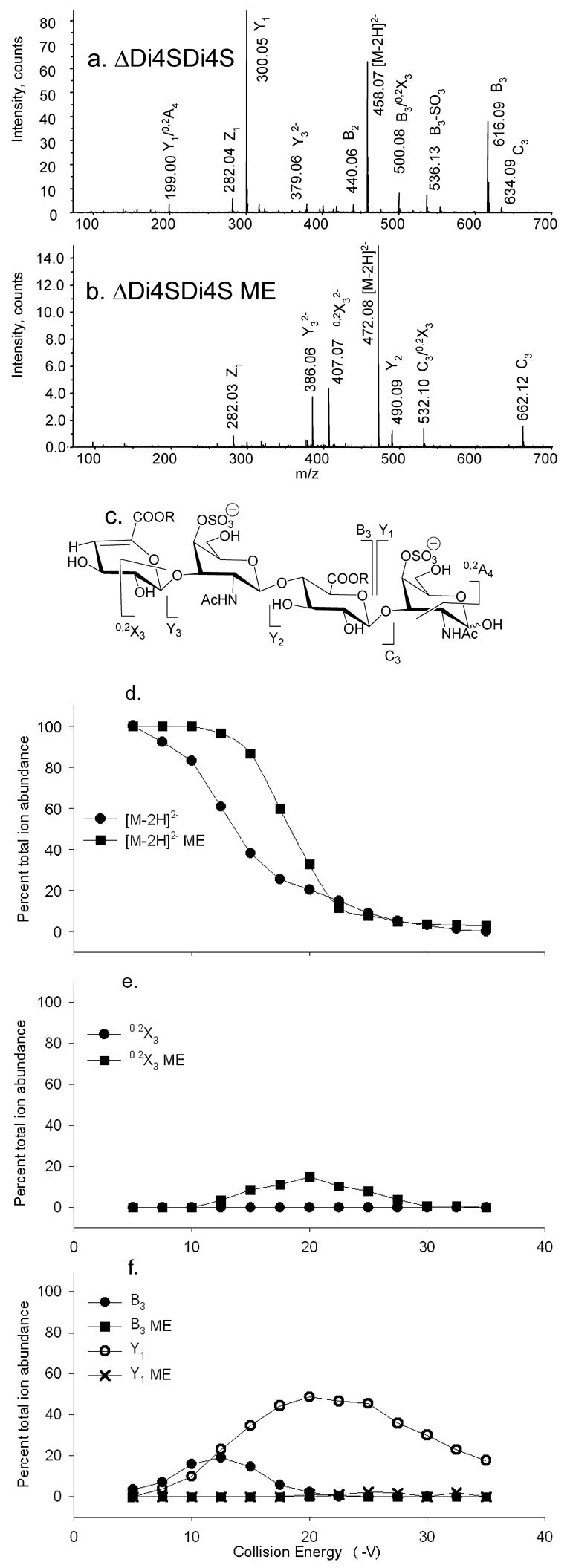

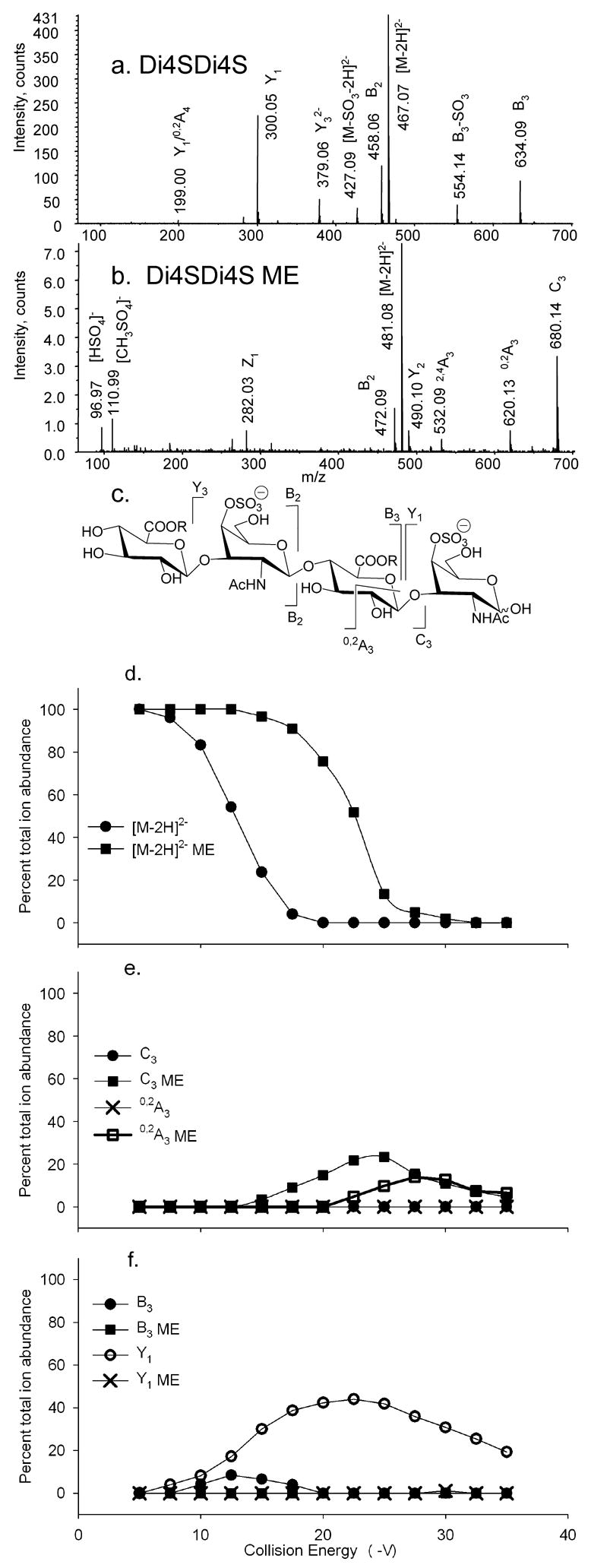

Figure 3.

CID product ion mass spectra of (a) ΔDi4SDi4S [M–2H]2−, CE −15.0 V, (b) ΔDi4SDi4S ME [M–2H]2−, CE −17.5 V. Trends in product ion formation are shown in (c). The product ions above the structures are abundant for native forms and those below for derivatized forms. R = H for ΔDi4SDi4S and R = CH3 for ΔDi4SDi4S ME. CID breakdown diagrams for (d) [M–2H]2− ΔDi4SDi4S (●) and [M–2H]2− ΔDi4SDi4S ME (■); (e) 0,2X3 ΔDi4SDi4S (●) and 0,2X3 ΔDi4SDi4S ME (■); (f) B3 ΔDi4SDi4S (●), B3 ΔDi4SDi4S ME (■), Y1 ΔDi4SDi4S (○) and Y1 ΔDi4SDi4S ME (×).

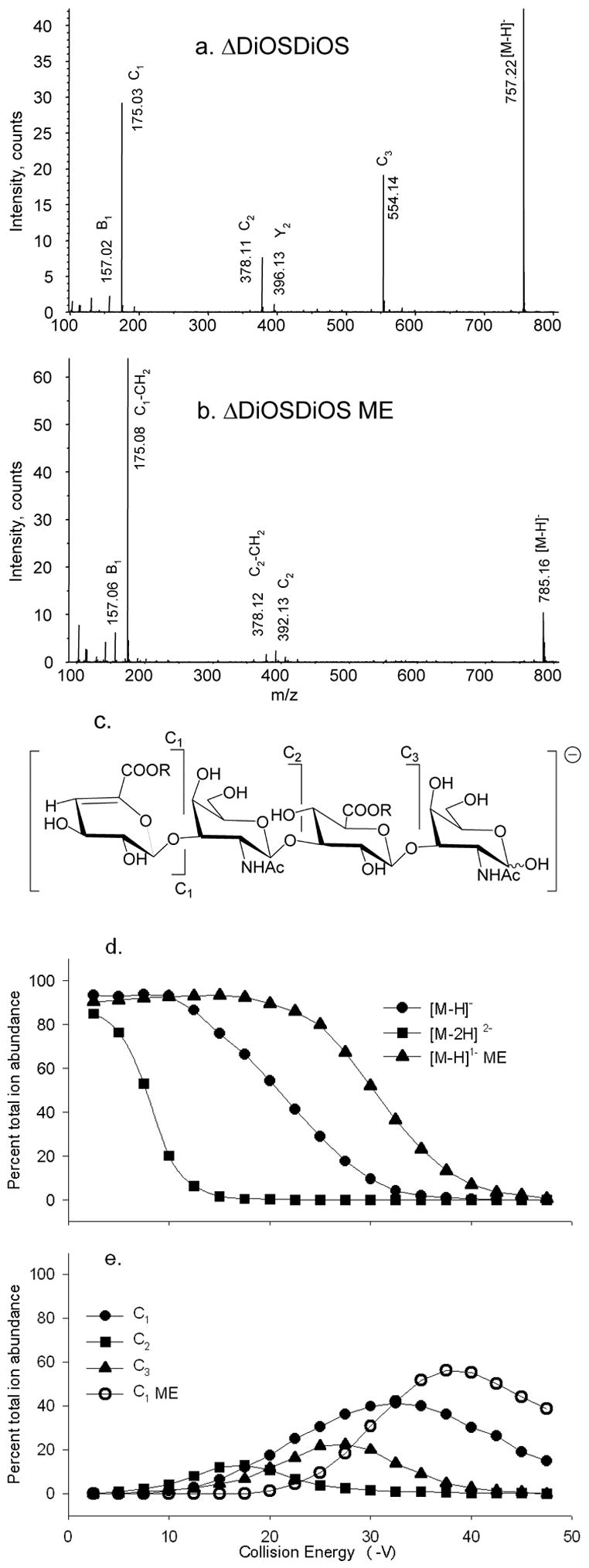

Figure 5.

Tandem mass spectra of (a) ΔDiOSDiOS [M–H]− at CE −22.5 V, (b) ΔDiOSDiOS ME [M–H]− at CE −37.5 V. Trends in product ion formation are shown in (c). The product ions above the structures are abundant for native forms and those below for derivatized forms. R = H for ΔDiOSDiOS and R = CH3 for ΔDiOSDiOS ME. CID breakdown diagrams for (d) [M–H]− ΔDiOSDiOS (●), [M–2H]2− ΔDiOSDiOS (■) and [M–H]− ΔDiOSDiOS ME (▲), (e) ΔDiOSDiOS [M–H]− C1 (●), C2 (■), C3 (▲) and ΔDiOSDiOS ME [M–H]− C1 (○).

Electrospray quadrupole orthogonal time-of-flight mass spectrometry

Mass spectra were acquired in the negative ion mode using an Applied Biosystems/MDS-Sciex API QSTAR™ Pulsar-I quadrupole orthogonal time-of-flight mass spectrometer. Samples were dissolved in water and diluted in sufficient volume of 30% methanol to achieve a 1 pmol/μL solution. Aliquots (3 μL) were infused into the mass spectrometer ion source using 1–2 μm orifice nanospray [33] tips pulled from thin-wall borosilicate glass capillaries (1.2-mm OD, 0.90-mm ID; World Precision Instruments, Sarasota, FL) using a Sutter Instrument P 80/PC micropipette puller (San Rafael, CA). Steady ion signal was typically observed using a needle potential of –1000 V and all spectra were calibrated externally. For CID breakdown diagrams, the collision energy was set initially to −5 V and stepped in 0.25 V increments to −40 V, with 0.5 to 1.0 min of acquisition per increment. Collision energies are expressed as their absolute values in the text and figures.

Results and discussion

Figure 1 shows tandem mass spectra of (a) ΔDi4S and (b) methyl esterified ΔDi4S methyl glycoside (ΔDi4S ME), acquired using collision energy sufficient to reduce the precursor ion abundance by approximately 50%. In (a), ΔDi4S produces both a glycosidic bond cleavage ion (Y1) and a cross-ring cleavage (0,2X1) in high abundance. The ΔDi4S ME (b) produces significantly lower abundances of ions from glycosidic bond cleavage (Y1) and the most abundant product ion corresponds to 0,2X1 cross-ring cleavage. Figure 1c shows the major product ions formed for the ΔDi4S disaccharide in diagram form. Ions that are abundant for native precursors are drawn above the structure, and those for methyl esterified precursors below. Figure 1d shows plots of precursor percent total ion abundances versus collision energy, for native and methyl esterified ΔDi4S. Significantly more collision energy is required in order to reduce the precursor ion abundances by 50% (16.5 vs. 23.0 V) after methyl esterification. The abundance of the 0,2X1 cross-ring cleavage ion increases (e) for ΔDi4S ME. The effect is significant, and is more pronounced for the 6-sulfated isomer, ΔDi6S (see supplementary Figure 1). The abundance of Y1 (f) decreases significantly, for ΔDi4S ME. Thus, cross-ring cleavages become the primary fragmentation pathway for ΔDi4S ME. The energy required for cross-ring cleavage increases only slightly after for ΔDi4S ME (e), consistent with the hypothesis that the absence of competing processes accounts for the increasing relative abundances of ions that derive from cross-ring cleavages. It is likely that the Y1 ion is formed by two processes: proton mediated glycosidic bond cleavage and secondary fragmentation of the 0,2X1 ion. For ΔDi4S ME, the latter process is favored. This conclusion is supported by tandem MS of Di4S [M–H]−, see below.

As shown in Figure 2, the tandem mass spectrum of Di4S [M–H]− ion, (a), differs from that of ΔDi4S [M–H]− in that the 0,2X1 ion is absent, probably because the formation of cross-ring cleavage ions is disfavored by the saturated uronosyl ring. Specifically, the saturated uronosyl ring does not allow for formation of the 0,2X1 through the retro-Diels Alder mechanism [32]. Methyl esterified Di4S methylglycoside (Di4S ME, b) produces neither glycosidic bond nor cross-ring cleavage ions in significant abundances. Replacement of the carboxyl proton with a methyl group evidently results in such stabilization of the glycosidic bond that formation of ions of composition [HSO4]− (m/z 96.97) and [CH3SO4]− (m/z 110.99) are more favored during the collisional heating process. The overall trends in product ion formation is shown in (c). The Di4S ME [M–H]− ion requires increased collision energy, relative to Di4S [M–H]−, to reduce the precursor ion abundance by 50% from 15.0 to 30.0 V, as shown in (d). The Y1 ion undergoes subsequent fragmentation to form Y1/0,2A2, a process that is favored at higher collision energies, as shown in (e). The formation of Y1 evidently enables 0,2A2 cleavage because the 3-position is no longer blocked. The Di4S ME forms neither Y1 nor Y1/0,2A2, even at the highest collision energies.

Figure 3 compares CID product ion mass spectra of (a) ΔDi4SDi4S [M–2H]2− and (b) methyl esterified ΔDi4SDi4S (ΔDi4SDi4S ME) [M–2H]2−. The most abundant ions in (a) are produced from cleavage of the reducing terminal glycosidic bond to form complementary B31− and Y11− ions. The product ion masses for ΔDi4SDi4S ME (b) are consistent with the methyl esterification of both uronosyl residues and an unmodified reducing end. Methyl esterification dramatically changes the product ion pattern. The most abundant product ions are now 0,2X32−, followed by Y32−, and ions of type B are absent. As will be discussed in the next paragraph, the Y32− and Y21− ions are not observed for the saturated Di4SDi4S ME precursor ion. This precursor ion does not undergo 0,2X-type fragmentation due to the absence of a non-reducing end Δ-unsaturated uronosyl ring. These observations are consistent with the conclusion that the Y32− and Y21− ions arise as sub-fragments of the 0,2X32− cleavage for the ΔDi4SDi4S ME precursor. An abundant C3 ion is observed, indicating that methyl esterification has changed the probabilities for the competing fragmentation pathways. Both the Y1 and Y1/0,2A4 ions are absent in the tande mass spectrum of ΔDi4SDi4S ME. The trend in product ion formation is shown diagrammatically in (c). Methyl esterification significantly increases the amount of energy required to reduce the precursor ion by 50% for the ΔDi4SDi4S (d) from 12.5 to 17.5 V. The abundance of the 0,2X3 ion is very low at all collision energies for ΔDi4SDi4S, but it is significantly increased after methyl esterification (e). As shown in (f), the abundances of the complementary B3 and Y1 ions are very low at all collision energies after methyl esterification, consistent with the carboxyl proton playing an important role in the formation B- and Y-type glycosidic cleavage ions. A C3 ion is present for methyl esterified ΔDi4SDi4S but subsequent Atype cleavage to the internal GlcA residue is not observed. The series 0,2X3→Y3→Y2 is evidently the favored pathway. The fact that C-type ions are abundant only after methyl esterification is consistent with the conclusion that deprotonation of the anomeric hydroxyl group occurs during the collisional heating process. This process becomes favorable only when lower energy fragmentation pathways are blocked by methyl esterification.

The native Di4SDi4S [M–2H]2− ion (Figure 4a) produces a pattern of glycosidic bond cleavage ions in which the 0,2X3 ion is absent. The methyl esterified Di4SDi4S precursor (b) produces an abundant C3 ion but does not yield 0,2X3 and Y3 ions. A-type product ions have been shown to arise from retro-aldol rearrangement of oligosaccharide ions in the negative mode [16, 17]. This mechanism requires an open-ring reducing terminal aldehyde, and such structures are formed by C-type fragmentation [23–25]. The 0,2A3 ion formed from cross-ring cleavage to the internal GlcA residue in Figure 4b is therefore likely to arise from the C3 ion by retro-aldol rearrangement. The results show that replacement of the carboxyl proton with a methyl group alters the product ion pathways by disfavoring formation of B- and Y-type ions and favoring Atype cleavage in the internal GlcA residue. The trends in product ion formation are illustrated in (c). As shown in (d), the amount of energy required to decrease the precursor ion abundance by 50% increased from 12.5 to 22.5 V, due to methyl esterification. The formation of 0,2X3 is not observed for Di4SDi4S, and the formation of C3 ions is observed (e). These ions subsequently form 0,2A3 ions as the energy increases. The formation of B3 and Y1 ions is favorable only for native Di4SDi4S, as shown in (f). In summary, native ions produce complementary B and Y-type glycosidic cleavages, and methyl esterified ions produce C- and A-type ions.

Figure 4.

CID product ion mass spectra of (a) Di4SDi4S [M–2H]2−, CE −12.5 V and (b) Di4SDi4S ME, CE −22.5 V. Trends in product ion formation are shown in (c). The product ions above the structures are abundant for native forms and those below for derivatized forms. R = H for Di4SDi4S and R = CH3 for Di4SDi4S ME. CID breakdown diagrams for (d) [M–2H]2− Di4SDi4S (●) and [M–2H]2− Di4SDi4S ME (■); (e) C3 Di4SDi4S (●) and C3 Di4SDi4S ME (■), 0,2A3 Di4SDi4S (×) and 0,2A3 Di4SDi4S ME (□); (f) B3 Di4SDi4S (●), B3 Di4SDi4S ME (■), Y1 Di4SDi4S (○) and Y1 Di4SDi4S ME (×).

Unsulfated ΔDiOSDiOS dissociates as an [M–H]− ion to form an abundant series of C-type ions, as shown in Figure 5a. Ions of type B and Y are observed in low abundances and are absent in the product ion profile of the [M–2H]2− ion (not shown). The ΔDiOSDiOS ME [M–H]− ion (b) forms a very abundant C1 ion, the m/z of which (175.03) is consistent with an unmodified HexA residue. A low abundance C2 ion with one methyl group is detected at m/z 392.13. The product ions formed are shown diagrammatically in (c). It appears that rearrangement to lose a methyl group during the formation of the C1 ion is the most facile fragmentation process for the methyl esterified molecular ion. In the absence of acidic groups, charge formation for the methyl esterified variant is likely to occur by deprotonation of a ring hydroxyl group. Such deprotonation results in an ion with significantly higher internal energy than that formed by deprotonation of an acidic group. As a result, fragmentation processes that require significantly higher energy become accessible.

The abundances of the ΔDiOSDiOS precursor ions as a function of collision energy are plotted in Figure 5d. The ΔDiOSDiOS [M–H]− ion (●)dissociates at significantly higher energies than does the [M–2H]2− ion (■). Despite the significant differences in dissociation energies, the overall product ion patterns are similar. The ΔDiOSDiOS ME [M–H]− ion requires the highest collision energy for dissociation. As shown in Figure 5e, native ΔDiOSDiOS [M–H]− dissociates to form a C2 ion (■) with maximum abundance at 17.5 V. It is likely that this ion dissociates again to form C1 ions (●). The C3 ion (▲) is observed with maximum abundance at 27.5 V, and may also undergo further fragmentation. The formation of the C1 ion from the methyl esterified ΔDiOSDiOS [M–H]− precursor ion (○) occurs with maximum abundance at 37.0V. It is likely that this ion is formed by rearrangement of the ester methyl group at elevated energies.

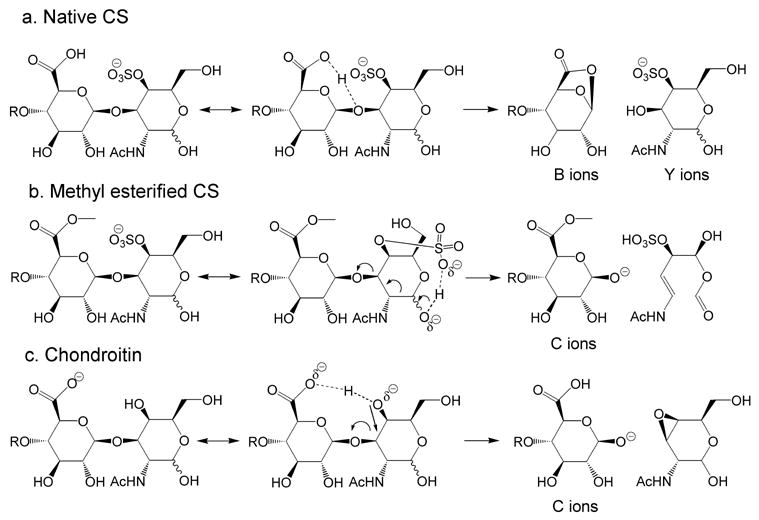

Scheme 1 shows proposed mechanisms for fragmentation of CS GAG ions with unmodified reducing ends in the negative low energy CID product ion mode. As shown in (a), native CS oligosaccharides produce abundant B- and Y-type ions, with comparatively low abundances of C- and X-type ions. For CS oligosaccharides of composition Δ (HexA)x(GalNAc)x(SO3)x, the most abundant charge state observed using negative ion ESI is typically equal to X. For such charge states, the most abundant population of precursor ions is one where each sulfate group is charged and the carboxyl groups are protonated. The observation of B- and Y-type ions is consistent with the conclusion that the carboxyl proton becomes delocalized during the collisional heating process and associates with a glycosidic oxygen atom. This association destabilizes the glycosidic bond in a manner similar to that described for oligosaccharides during positive mode CID [14, 34]. For methyl esterified CS GAG oligosaccharides (b), the carboxyl protons are replaced with methyl groups, and significantly more energy is required for fragmentation. The fact that abundant C31− is observed for the methyl esterified ΔDi4SDi4S and Di4SDi4S ion is consistent with the deprotonation of a reducing-terminal hydroxyl group with subsequent re-arrangement to eliminate the reducing end residue as a neutral fragment [25]. Such an event could take place during collisional heating, as shown in (b). The lower basicity of the SO3− group relative to COO− explains the increased energy required in order to produce this rearrangement. The ΔDiOSDiOS tetramer lacks sulfate groups and forms C-type ions for both 1- and 2- precursor ion charge states. This observation is consistent with the conclusion that the interplay between COOH and SO3− groups is necessary for the observation of complementary B- and Y-type ion pairs. The data show that C-type ion formation is considerably more facile for ΔDiOSDiOS, consistent with the conclusion, as shown in (c), that a proton from a ring hydroxyl group to the carboxylate anion during the heating process. The formation of C-type ions from ΔDiOSDiOS occurs at a lower energy because of the diminished barrier to transferring a proton to a carboxyl group. In summary, C-type ions are favored in the negative mode when either sulfate or carboxylate groups are present in the oligosaccharide structure. When both are present, the availability of a mobile proton results in formation of B- and Y-type ion pairs.

Scheme 1.

Proposed mechanisms for formation low energy negative ion CID product ions (a) Band Y-type ions for oligosaccharides derived from CS with unmodified reducing ends, (b) C-type ions from methyl esterified oligosaccharides derived from CS and (c) C-type ions from oligosaccharides derived from chondroitin.

Conclusions

It is useful to classify carbohydrates based on their acidic properties. Neutral glycans produce abundant C-type ions during negative dissociation. Sialylation dramatically increases the amount of energy necessary to induce fragmentation, and, although many of the same ion types are observed, the abundances of cross-ring cleavages to branching residues decreases [27]. Sulfated oligosaccharides lacking other acidic groups produce abundant C-type ions but require still higher collision energies to induce fragmentation. The presence of sulfate and uronic acids together, however, results in formation of ions of B- and Y-types, in a pattern similar to that observed for glycans in positive ions tandem MS. This pattern is attributed here to the interplay between sulfate and carboxylate groups, resulting in the availability of protons that become mobilized during the dissociation process. It is notable that mobile protons play roles in peptide fragmentation, explaining the observation of enhanced backbone cleavages adjacent to acidic amino acid residues [35].

Because released glycans are composed of glycoform mixtures, the compositions of many of which are isomeric, it is essential to gain a clear understanding of the tandem mass spectra. This and earlier work demonstrates that conditions for product ion analysis depends strongly on the compound class. Differentiation of isomers based on tandem mass spectrometric product ion abundances depends on an accurate understanding of the mechanisms behind the formation of product ions. This entails (1) the use of collision energies appropriate for the glycan composition in question, and (2) accurate understanding of the variation of product ion abundances for different structural isomers. In order to analyze glycan mixtures successfully, it is essential to tailor the collision energy to the glycan composition. This argues for separation of mixtures based on acidities using graphitized carbon, normal phase, or anion exchange chromatography prior to on- or off-line tandem mass spectrometric analysis. The separation step facilitates the use of appropriate tandem mass spectrometric collision energies for each glycan compositional class. Attempts to use a single set of fragmentation parameters for all glycans present in an unfractionated mixture are likely to result in over-fragmentation of fragile ions and under-fragmentation of more robust species.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIH grants P41RR10888 and R01HL74197.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Zhang Y, Kariya Y, Conrad AH, Tasheva ES, Conrad GW. Analysis of keratan sulfate oligosaccharides by electrospray ionization tandem mass spectrometry. Anal Chem. 2005;77:902–10. doi: 10.1021/ac040074j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Oguma T, Toyoda H, Toida T, Imanari T. Analytical Method for Keratan Sulfates by High-Performance Liquid Chromatography/Turbo-Ionspray Tandem Mass Spectrometry. Anal Biochem. 2001;290:68–73. doi: 10.1006/abio.2000.4940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lamb DJ, Wang HM, Mallis LM, Linhardt RJ. Negative ion fast-atom bombardment tandem mass spectrometry to determine sulfate and linkage position in glycosaminoglycan derived disaccharides. J Am Soc Mass Spectrom. 1992;3:797–803. doi: 10.1016/1044-0305(92)80002-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zaia J, McClellan JE, Costello CE. Tandem mass spectrometric determination of the 4S/6S sulfation sequence in chondroitin sulfate oligosaccharides. Anal Chem. 2001;73:6030–6039. doi: 10.1021/ac015577t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Desaire H, Sirich TL, Leary JA. Evidence of block and randomly sequenced chondroitin polysaccharides: sequential enzymatic digestion and quantification using ion trap tandem mass spectrometry. Anal Chem. 2001;73:3513–3520. doi: 10.1021/ac010385j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zamfir A, Seidler DG, Kresse H, Peter-Katalinc J. Structural characterization of chondroitin/dermatan sulfate oligosaccharides from bovine aorta by capillary electrophoresis and electrospray ionization quadrupole time-of-flight tandem mass spectrometry. Rapid Commun Mass Spectrom. 2002;16:2015–2024. doi: 10.1002/rcm.820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zamfir A, Seidler DG, Schonherr E, Kresse H, Peter-Katalinic J. On-line sheathless capillary electrophoresis/nanoelectrospray ionization-tandem mass spectrometry for the analysis of glycosaminoglycan oligosaccharides. Electrophoresis. 2004;25:2010–6. doi: 10.1002/elps.200405925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McClellan JM, Costello CE, O’Connor PB, Zaia J. Influence of charge state on product ion mass spectra and the determination of 4S/6S sulfation sequence of chondroitin sulfate oligosaccharides. Anal Chem. 2002;74:3760–3771. doi: 10.1021/ac025506+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mallis LM, Wang HM, Loganathan D, Linhardt RJ. Sequence analysis of highly sulfated, heparin-derived oligosaccharides using fast atom bombardment mass spectrometry. Anal Chem. 1989;61:1453–1458. doi: 10.1021/ac00188a030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Saad OM, Leary JA. Compositional analysis and quantification of heparin and heparan sulfate by electrospray ionization ion trap mass spectrometry. Anal Chem. 2003;75:2985–95. doi: 10.1021/ac0340455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Naggar EF, Costello CE, Zaia J. Competing fragmentation processes in tandem mass spectra of heparin-like glycosaminoglycans. J Am Soc Mass Spectrom. 2004;15:1534–44. doi: 10.1016/j.jasms.2004.06.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zaia J, Costello CE. Tandem mass spectrometry of sulfated heparin-like glycosaminoglycan oligosaccharides. Anal Chem. 2003;75:2445–2455. doi: 10.1021/ac0263418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Orlando R, Bush CA, Fenselau C. Structural-analysis of oligosaccharides by tandem mass-spectrometry - collisional activation of sodium adduct ions. Biomed Environ Mass Spectrom. 1990;19:747–754. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hofmeister GE, Zhou Z, Leary JA. Linkage position determination in lithium-cationized disaccharides - tandem mass-spectrometry and semiempirical calculations. J Am Chem Soc. 1991;113:5964–5970. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ngoka LC, Gal JF, Lebrilla CB. Effects of cations and charge types on the metastable decay rates of oligosaccharides. Anal Chem. 1994;66:692–8. doi: 10.1021/ac00077a018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dallinga JW, Heerma W. Reaction mechanism and fragment ion structure determination of deprotonated small oligosaccharides, studied by negative ion fast atom bombardment (tandem) mass spectrometry. Biol Mass Spectrom. 1991;20:215–31. doi: 10.1002/bms.1200200410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Spengler B, Dolce JW, Cotter RJ. Infrared-Laser Desorption Mass-Spectrometry of Oligosaccharides - Fragmentation Mechanisms and Isomer Analysis. Anal Chem. 1990;62:1731–1737. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Carroll J, Willard D, Lebrilla C. Energetics of cross-ring cleavages and their relevance to the linkage determination of oligosaccharides. Analytica Chimica Acta. 1995;307:431–447. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Harvey DJ, Naven TJP, Küster B, Bateman RH, Green MR, Critchley G. Comparison of fragmentation modes for the structural determination of complex oligosaccharides ionized by matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization mass spectrometry. Rapid Commun Mass Spectrom. 1995;9:1556–1561. doi: 10.1002/rcm.1290091517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Harvey DJ, Bateman RH, Green MR. High-energy collision-induced fragmentation of complex oligosaccharides ionized by matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization mass spectrometry. J Mass Spectrom. 1997;32:167–187. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9888(199702)32:2<167::AID-JMS472>3.0.CO;2-Q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zaia J. Mass spectrometry of oligosaccharides. Mass Spectrom Rev. 2004;23:161–227. doi: 10.1002/mas.10073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Domon B, Costello CE. A systematic nomenclature for carbohydrate fragmentations in FAB-MS/MS spectra of glycoconjugates. Glycoconjugate J. 1988;5:397–409. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chai W, Piskarev V, Lawson AM. Negative-Ion electrospray mass spectrometry of neutral underivatized oligosaccharides. Anal Chem. 2001;73:631–657. doi: 10.1021/ac0010126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pfenninger A, Karas M, Finke B, Stahl B. Structural analysis of underivatized neutral human milk oligosaccharides in the negative ion mode by nano-electrospray MSn (part 2: application to isomeric mixtures) J Am Soc Mass Spectrom. 2002;13:1341–8. doi: 10.1016/S1044-0305(02)00646-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pfenninger A, Karas M, Finke B, Stahl B. Structural analysis of underivatized neutral human milk oligosaccharides in the negative ion mode by nano-electrospray MSn (part 1: methodology) J Am Soc Mass Spectrom. 2002;13:1331–40. doi: 10.1016/S1044-0305(02)00645-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Li DT, Her GR. Linkage analysis of chromophore-labeled disaccharides and linear oligosaccharides by negative ion fast atom bombardment ionization and collisional-induced dissociation with B/E scanning. Anal Biochem. 1993;211:250–7. doi: 10.1006/abio.1993.1265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Seymour JL, Costello CE, Zaia J. The influence of sialylation on glycan negative ion dissociation and energetics. J Am Soc Mass Spectrom. 2006;17:844–854. doi: 10.1016/j.jasms.2006.02.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dell A, Morris HR, Egge H, von Nicolai H, Strecker G. Fast-atom bombardment mass spectrometry for carbohydrate structure determination. Carbohydr Res. 1983;115:41–52. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dell A, Oates JE, Morris HR, Egge H. Structure determination of carbohydrates and glycosphingolipids by fast atom bombardment mass spectrometry. Int J Mass Spectrom Ion Phys. 1983;46:415–418. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Egge H, Dell A, Von Nicolai H. Fucose containing oligosaccharides from human milk. I. Separation and identification of new constituents. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1983;224:235–253. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(83)90207-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Carr SA, Reinhold VN. Structural characterization of sulfated glycosaminoglycans by fast atom bombardment mass spectrometry: application to chondroitin sulfate. J Carbohydr Chem. 1984;3:381–401. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6215(00)90088-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Saad OM, Leary JA. Delineating mechanisms of dissociation for isomeric heparin disaccharides using isotope labeling and ion trap tandem mass spectrometry. J Am Soc Mass Spectrom. 2004;15:1274–86. doi: 10.1016/j.jasms.2004.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wilm MS, Mann M. Electrospray and Taylor-cone theory, Dole’s beam of macromolecules at last? Int J Mass Spectrom Ion Processes. 1994;136:167–180. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cancilla MT, Penn SG, Carroll JA, Lebrilla CB. Coordination of alkali metals to oligosaccharides dictates fragmentation behavior in matrix assisted laser desorption ionization/Fourier transform mass spectrometry. J Am Chem Soc. 1996;118:6736–6745. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wysocki VH, Tsaprailis G, Smith LL, Breci LA. Mobile and localized protons: a framework for understanding peptide dissociation. J Mass Spectrom. 2000;35:1399–406. doi: 10.1002/1096-9888(200012)35:12<1399::AID-JMS86>3.0.CO;2-R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.