Abstract

OBJECTIVE

To examine the extent to which US adults use herbs (herbal supplements) in accordance with evidence-based indications.

PARTICIPANTS AND METHODS

The Alternative Health supplement of the 2002 National Health Interview Survey (NHIS) is part of an annual, nationally representative survey of US adults. It contains data on adults’ use of the 10 herbs most commonly taken to treat a specific health condition in the past year (January 1 to December 31, 2002). The Natural Standard database was used to formulate evidence-based standards for herb use. These standards were applied to the NHIS data to identify groups of people who used herbs appropriately and inappropriately, using a multivariable logistic regression model.

RESULTS

Of the 30,617 adults surveyed, 5787 (18.9%) consumed herbs in the past 12 months; of those, 3315 (57.3%) used herbs to treat a specific health condition. Among people who used only 1 herb (except echinacea and ginseng), approximately one third used it consonant with evidence-based indications. Women and people with a college education were more likely to use herbs (with the exception of echinacea) concordant with scientific evidence. Adults younger than 60 years and black adults were significantly less likely to use herbs (with the exception of echinacea) based on evidentiary referents than their counterparts. However, for echinacea users, no significant differences were detected.

CONCLUSION

Roughly two thirds of adults using commonly consumed herbs (except echinacea) did not do so in accordance with evidence-based indications. Health care professionals should take a proactive role, and public health policies should disseminate evidence-based information regarding consumption of herbal products.

Since the early 1990s, the use of complementary and alternative medicine, including dietary supplements, has increased substantially. A benchmark national survey revealed that in the United States use of any complementary and alternative medicine modality increased from 33.8% in 1990 to 42.7% in 1997,1 and a 2002 study found that 62% of those surveyed used some form of complementary and alternative medicine in the past 12 months.2 Specifically, dietary supplement use has increased substantially, with herbal supplement use increasing more than use of other complementary and alternative medicine modalities.1,3,4 Sales of dietary supplements increased from $8.8 billion in 1994 to an estimated $15.7 billion in 2000 and $18.8 billion in 2003; this is an increase of more than 100% in the past 10 years.5–7

One important reason why dietary supplement use has increased is that these agents have become more widely available, in part because of the minimal regulatory requirements for safety and efficacy compared with regulatory requirements for drugs.8,9 The Dietary Supplement Health and Education Act (DSHEA) of 1994 established that dietary supplements (including herbal supplements) be regulated under a Food and Drug Administration (FDA) category separate from both foods and drugs. By doing this, the burden for demonstrating product safety was shifted from manufacturers of dietary supplements to the FDA.9 Under DSHEA, before the FDA can remove a dietary supplement from the market, it must first prove that it is unsafe. This has raised concerns about the safety of these herbal products because they could have adverse effects10 that consumers are less likely to report11; furthermore, herbs may be adulterated12,13 or have the potential to interact with therapeutic drugs.14,15

As the use of herbal supplements increased, so did the number of clinical trials evaluating them.16 Thus, some herbal supplements now have evidence-based indications derived from scientific data.17 However, under DSHEA, product labels cannot claim to “diagnose, treat, cure, or prevent any disease” but rather can claim only that their product may support the “structure and function of the body.” This has raised concerns that the DSHEA guidelines may not be followed and moreover may confuse consumers.18 Although health care professionals know how to access clinical trial results and have access to reliable information about herbal products, this information may not reach the consumer because most patients do not discuss their herbal medication use with their health care professionals.1 In addition, approximately half of consumers believe that their physicians are prejudiced against supplement use.19 Hence, consumers may not fully understand the intended scientific use of particular herbal products.

Therefore, it is important to understand whether herbal supplements (herbs) are being used on the basis of available scientific data. However, research examining the basis on which consumers use these products is scant. Whether consumers are using herbs based on scientific evidence, folklore, or tradition is unclear. The aims of this study were to examine indications that consumers report for taking individual herbs and to determine whether these are consonant with available evidence. To do this, we used data from the National Health Interview Survey (NHIS)20 to identify the proportion of respondents taking various herbs consonant with evidence-based indications and evaluate factors that predict evidence-based use.

PARTICIPANTS AND METHODS

This study is based on data from the Alternative Health/Complementary and Alternative Medicine supplement, the Sample Adult Core component, and the Family Core component of the 2002 NHIS.20 The NHIS is an ongoing cross-sectional survey of a nationally representative sample of the civilian noninstitutionalized household population of the United States. Both basic health and demographic information are collected on all household members, generally on the basis of a face-to-face interview, but proxy responses are also accepted. Additional information is collected per family on 1 randomly selected adult who is 18 years or older (sample adult) and 1 randomly selected child who is 0 to 17 years old (sample child). Information on the sample adult is generally self-reported. In the 2002 NHIS study, 31,044 sample adults completed interviews, a response rate of 74.3%.

The Alternative Medicine supplemental questionnaire was developed in part with the National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine at the National Institutes of Health and administered as part of the adult questionnaire. The survey had a separate section on dietary supplements and distinguished “natural herbs” from vitamins and minerals. It queried whether particular herbs were used in the past 12 months and if so whether they were taken to treat a specific health condition. If consumers reported a particular clinical indication for an herb, they were further asked to identify it from a list of 73 specific health conditions. They were also asked to list independently herbs they took in the past 12 months from a list of 35 commonly used herbal supplements.

We used this NHIS database to select the eligible population. We analyzed only people who, from January 1 to December 31, 2002, took a single herb from the list of 35 and who said they were taking it to treat a specific health condition. Only single-herb users were analyzed because the questionnaire design did not link each herb consumed with a specific health condition; thus, it was not possible to assess the corresponding indication if a person took more than 1 herb.

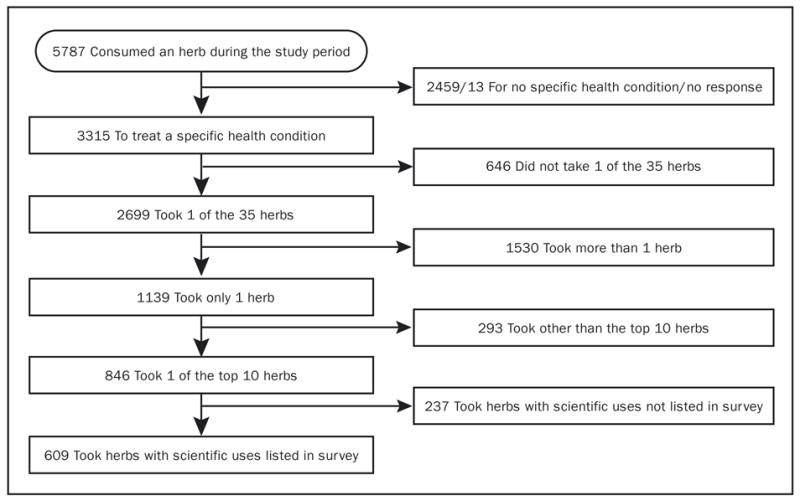

A flowchart describing selection of the eligible population is shown in Figure 1. The total sample population was 30,617 (after excluding 427 not ascertained, refused, or do not know responses): 7665 (25.0%) used natural herbs for their own health, and 5787 (18.9%) used herbs for the period studied. Of those who used herbs during the study period, 3315 (57.3%) used them to treat a specific health condition. A total of 2699 used at least 1 of the 35 products listed in the questionnaire; of these, 1139 (42.2%) used only 1 herb. After limiting the study population further to those who took 1 of the top 10 most commonly used herbs and focusing on those respondents who reported health conditions that were included in the NHIS list, the final study population consisted of 609 adults.

FIGURE 1.

Flowchart of study population selection.

We initially included the 10 most commonly endorsed herbs in the survey for analyses: echinacea, ginseng, ginkgo, garlic, St John’s wort, peppermint, ginger, soy, ragweed, and kava-kava. We used the Natural Standard database resource17 to formulate evidence-based indications for the selected herbs (Table 1). Natural Standard is “an international research collaboration that aggregates and synthesizes data on complementary and alternative therapies.”

TABLE 1.

| Rank of herb in terms of use | Herbal supplement | Evidence-based indication of benefit | All uses listed in survey? | Included in analysis? |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Echinacea | Upper respiratory tract infections | Yes | Yes |

| 2 | Ginkgo | Claudication, dementia, cerebral insufficiency† | No | No |

| 3 | Ginger | Nausea and vomiting† | No | No |

| 4 | Garlic | High cholesterol level | Yes | Yes |

| 5 | Ginseng | Mental performance, ‡ diabetes | Yes | Yes |

| 6 | Kava-kava | Anxiety | Yes | Yes |

| 7 | Soy | High cholesterol level, source of protein, menopausal hot flashes | Yes | Yes |

| 8 | St John’s wort | Depression | Yes | Yes |

| 9 | Ragweed | No established use | … | No |

| 10 | Peppermint | No established use | … | No |

All indications listed had a scientific evidence level of A or B and thus had at least 1 randomized controlled trial that demonstrated the efficacy of the herb for the particular condition.

Claudication, dementia, cerebral insufficiency, nausea, and vomiting were not directly listed in the 73 specific conditions of the National Health Interview Survey.

Although ginseng was indicated for “mental performance” in the Natural Standard database, mental performance was not listed in the National Health Interview Survey as a health condition and thus was excluded from analyses. The only other indication for ginseng in the Natural Standard database identified as containing level A or B evidence was diabetes; because diabetes was also present in the National Health Interview Survey list of health conditions, it was the only health condition included in our analyses.

Using a comprehensive methodology and reproducible grading scales, information is given that is evidence based, consensus based, and peer reviewed, tapping into the collective expertise of a multidisciplinary editorial board. Natural Standard is widely recognized as one of the world’s premier sources of information in this area.17 All the indications listed in Table 1 had a scientific evidence level of A or B and thus had good to strong evidence, suggested by at least 1 randomized controlled trial demonstrating the efficacy of the herb for a particular condition. We believe that the rankings reflect the principles of evidence-based medicine evaluations.

Of the 10 herbs initially considered for this study, we were not able to assess ginkgo for claudication, dementia, or cerebral insufficiency or ginger for nausea or vomiting because these were not listed in the survey’s 73 specific health conditions. The Natural Standard database does not identify any established scientific use of peppermint or ragweed, so respondents taking those herbs were excluded from analyses. Thus, our eligible population included individuals taking 1 of 6 herbs (echinacea, garlic, ginseng, kava-kava, soy, or St John’s wort) in the past 12 months (Table 1).

Descriptive statistics of the demographic variables (mean ± SD and range for age; count and percentages for sex, race, and education) were computed for the study population and to examine the demographic patterns of herb use. For the scientific basis of herb use, a multivariable logistic regression model was fitted to assess the differences among the various herbs used (echinacea, ginseng, garlic, St John’s wort, soy supplement, and kava-kava) as the primary independent variable of interest, with sex, age, ethnicity, and education as covariates. Similarly, 2 other multivariable logistic regression models were fitted to examine the effect of age, sex, ethnicity, and education on the decision to take herbs on the basis of scientific evidence: (1) all herbs combined not including echinacea and (2) only echinacea users. The results are reported as odds ratios (ORs) with respective 95% confidence intervals (CIs). To incorporate the complex sampling design and sampling weights of the NHIS in the statistical analysis, SAS (version 9.1, SAS Institute Inc, Cary, NC) procedures SURVEYFREQ and SURVEYLOGISTIC were used. P<.05 was considered statistically significant. These procedures use the Taylor expansion method to estimate sampling errors of estimators based on complex sample designs. This study is part of a project that was approved by the University of Iowa Institutional Review Board.

RESULTS

Of 609 eligible study participants, 64.8% were women and the mean ± SD age of the population was 41.4 ± 14 years (range, 18–85 years). Most of the eligible population (81.3%) was white (non-Hispanic white), with 8.1% being black, 7.9% Hispanic, and the remaining 2.7% of other ethnicity. Approximately one fourth (25.9%) of the eligible participants had an education level lower than or equal to a high school diploma, 59.1% had a post–high school or college equivalent education, and 15.0% had a graduate or professional equivalent education.

Estimates of the proportion of adults using 1 study herb, in accordance with evidence-based indications, are given in Table 2. Overall, 54.9% used herbs consistent with evidence-based indications. Use of herbs in accordance with evidence-based standards ranged from a high of 68.0% for echinacea to a low of 3.8% for ginseng. Roughly one third of those using each of the remaining 4 herbs did so in accordance with Natural Standard indications.

TABLE 2.

Consumers’ Use of Herbs Based on Natural Standard Indications

| Herbs | No. of users | No. of evidenced-based users | Use based on evidence, % (95% CI)* |

|---|---|---|---|

| Echinacea | 427 | 286 | 68.0 (63.2–72.9) |

| Ginseng | 45 | 2 | 3.8 (0.0–8.9) |

| Garlic | 59 | 14 | 27.4 (13.6–41.1) |

| St John’s wort | 48 | 19 | 31.6 (17.2–46.0) |

| Soy supplement | 20 | 9 | 33.5 (10.4–56.7) |

| Kava-kava | 10 | 4 | 36.1 (5.5–66.7) |

| Total | 609 | 334 | 54.9 (50.6–59.3) |

Weighted estimate. CI = confidence interval.

For the other herbs combined (except echinacea), women (OR, 1.81; 95% CI, 1.23–2.67) and those with higher education (college education: OR, 1.55; 95% CI, 1.10–2.20; graduate college education: OR, 2.91; 95% CI, 1.13–7.45) were more likely to use the herbs based on their scientific merit than their counterparts (Table 3). In contrast, black people (OR, 0.51; 95% CI, 0.38–0.69) and younger adults (<40 years: OR, 0.43; 95% CI, 0.24–0.77; 40–59 years: OR, 0.48; 95% CI, 0.28–0.82) were significantly less likely to use herbs in accordance with evidence-based standards.

TABLE 3.

Proportion of Consumers Using Herbs Based on Natural Standard Indications, Stratified by Herb and Demographic Variables*

| Herbs combined (except echinacea)

|

Echinacea

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Evidence-based use (%)† (n=48) | Adjusted OR (95% CI) ‡ | P value | Evidence-based use (%)† (n=286) | Adjusted OR (95% CI) ‡ | P value |

| Sex | ||||||

| Female | 27.6 | 1.81 (1.23–2.67) | .003 | 66.7 | 0.84 (0.58–1.21) | .34 |

| Male | 17.5 | Referent | 70.3 | Referent | ||

| Age (y) | ||||||

| 18–39 | 18.5 | 0.43 (0.24–0.77) | .005 | 67.7 | 1.15 (0.59–2.25) | .68 |

| 40–59 | 24.5 | 0.48 (0.28–0.82) | .007 | 69.2 | 1.24 (0.64–2.40) | .53 |

| ≥60 | 33.0 | Referent | 63.7 | Referent | ||

| Race | ||||||

| Hispanic | 23.8 | 0.71 (0.45–1.11) | .71 | 60.4 | 0.71 (0.45–1.11) | .13 |

| Black§ | 16.3 | 0.51 (0.38–0.69) | <.001 | 76.2 | 1.61 (0.64–4.07) | .31 |

| Other | 0.0 | … | … | 67.8 | 1.03 (0.38–2.78) | .95 |

| White§ | 25.8 | Referent | 68.0 | Referent | ||

| Education// | ||||||

| Graduate school | 35.3 | 2.91 (1.13–7.45) | .03 | 69.0 | 0.83 (0.45–1.55) | .56 |

| >High school or college | 24.2 | 1.55 (1.10–2.20) | .01 | 66.5 | 0.76 (0.51–1.14) | .19 |

| ≤High school | 19.3 | Referent | 71.1 | Referent | ||

CI = confidence interval; OR = odds ratio.

Weighted estimate.

Multivariable logistic regression model with age, sex, ethnicity, and education as covariates was used to compute the ORs, 95% CIs, and respective P values.

Non-Hispanic.

Two echinacea users had missing education data.

For echinacea, we failed to see any such pattern (Table 3). Although minor differences in use were found among people with different demographic characteristics, the differences were not statistically significant.

DISCUSSION

To our knowledge, this is the first large US population–based study of whether consumers use herbs in accordance with evidence-based indications. Although previous studies have explored the reasons why people take supplements, they did not generally evaluate the use based on an external, evidence-based standard, and most studies did not evaluate individual herbs. Previous studies have reported that people use herbal supplements to promote general health21–23 and to treat or prevent symptomatic conditions (particularly chronic pain, musculoskeletal conditions, digestive problems, and common colds)1,24–27 and serious chronic illnesses (particularly cardiovascular disease and cancer).28,29 A study by Satia-Abouta et al30 found that people with medical conditions tend to use supplements more than others and commented that, although some people take supplements based on efficacy, many do not; however, this statement was not further quantified.

We found that only approximately one third of eligible survey participants were using 4 of 6 study herbs (echinacea and ginseng being the exceptions) in accordance with evidence-based indications. This finding may in part be due to a lack of information reaching consumers. Furthermore, health care professionals may not often be a major source of herbal product information for patients. Although manufacturers of herbal supplements can legally claim that their products are consistent with “structure and function” indications, they cannot claim that their products cure or treat specific conditions. Nonetheless, commercial advertising may imply disease indications, and other information sources, such as friends and relatives, may rely more on traditional use rather than scientific evidence.31–33

Reasons for the relatively low use of ginseng in accordance with the evidence-based indication listed in the Natural Standard database (diabetes) are not entirely clear. Perhaps consumers do not readily make distinctions between use of herbs “to treat a specific health problem or condition,” as was queried in the NHIS, and health promotion, especially because this distinction may not be apparent in the marketing of dietary supplements.34,35 Thus, it is possible that some respondents, although using ginseng for health promotion reasons, inadvertently endorsed the NHIS item on using herbs for health conditions.

It is also possible that some people who were using an herb “correctly” did not base their decisions on scientific evidence but were classified as “correct” users because scientific studies confirmed an herb’s traditional indications. This theory cannot be established because the NHIS questionnaire is cross-sectional and does not reveal the user’s source of information. Future studies need to explore this issue.

The way in which demographics affected the use of herbal products was of interest. Although approximately two thirds of respondents used echinacea concordant with the Natural Standard indications, only one third of users of other herbs (except ginseng) did so. Women, older persons, non-Hispanic white people, and those with higher education had higher rates of use concordant with Natural Standard indications, but no pattern emerged for echinacea. The reason for this discrepancy may be that for many years echinacea has consistently been the most commonly used herb, and many consumers believe it is effective for the common cold.1,2,19

Of interest, the efficacy of echinacea for the prevention or treatment of the common cold is in question according to recent studies.36 However, this should not be a major source of bias because the survey was conducted in 2002 and the Natural Standard database used in this study was primarily based on evidence that was relevant in 2002. For other less widely consumed herbs, certain demographic segments may not be accessing such general knowledge. This hypothesis is supported by the fact that these same demographic characteristics correlate with herb use in general. National surveys have shown that herbs are more commonly consumed by certain groups, including women, white people, older persons, and those with higher education.2,37–39 Thus, plausibly these consumers are more savvy and understand the evidence-based indications for the herbal products that they consume.

This study has a few limitations. First, all information was self-reported, which may cause problems with both the validation of herbal product use and the attributed medical conditions, but there is little ability to conduct this validation in a survey of this magnitude. Second, we did not include respondents who reported use of more than 1 herb because the data set was not structured to evaluate indications for multiple herb use; furthermore, those taking multiple herbal products may have different characteristics than single-herb users. Third, scientific indications were based on the Natural Standard database published in 2005 (with most references updated through 2002), and although the Natural Standard is a standard, well-respected, and evidence-based resource on herbal supplements, other evidence-based referents may yield additional information on the efficacy of herbs for treating specific health conditions. Also, the evidence base for certain herbs may have changed (as noted previously, an article in 2005 suggested that echinacea is ineffective for the common cold36). However, although this could limit the generalizability of this study to 2002, it does not threaten the internal validity of the study because the survey was conducted in 2002 and the Natural Standard database used in this study was primarily based on evidence that was relevant in 2002. Finally, since the survey provided no information on specific products or dosages, we do not know whether people taking the products appropriately took them at the recommended dosages and schedules.

Major strengths of the study are that the data came from a survey of a nationally representative sample of US adults, allowing us to make general demographic assessments and increasing the generalizability of the study findings. Furthermore, the selection of only single-herb users provided an opportunity to assess the individual herb. We clearly specified selection of herbs based on the national findings and not based on disease occurrence. Finally, the study’s large sample size enabled us to analyze specific herbs to discern variation among them.

CONCLUSION

With the exception of echinacea and ginseng, two thirds of respondents did not use commonly consumed herbs in consonance with a scientific standard. These results suggest that physicians, pharmacists, and other health care professionals should proactively educate consumers and advocate public health policies that would disseminate evidence-based information on the appropriate use of herbs. Further research is needed to confirm the study findings and evaluate mechanisms that enhance evidence-based use of herbal supplements.

Acknowledgments

This work was made possible by grant P01 ES012020 from the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences and the Office of Dietary Supplements, National Institutes of Health. Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences, National Institutes of Health.

- CI

confidence interval

- DSHEA

Dietary Supplement Health and Education Act

- FDA

Food and Drug Administration

- NHIS

National Health Interview Survey

- OR

odds ratio

References

- 1.Eisenberg DM, Davis RB, Ettner SL, et al. Trends in alternative medicine use in the United States, 1990–1997: results of a follow-up national survey. JAMA. 1998;280:1569–1575. doi: 10.1001/jama.280.18.1569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barnes PM, Powell-Griner E, McFann K, Nahin RL. Complementary and Alternative Medicine Use Among Adults: United States, 2002. Hyattsville, Md: National Center for Health Statistics; 2004. Advance Data From Vital and Health Statistics, No. 343. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Slesinski MJ, Subar AF, Kahle LL. Trends in use of vitamin and mineral supplements in the United States: the 1987 and 1992 National Health Interview Surveys. J Am Diet Assoc. 1995;95:921–923. doi: 10.1016/s0002-8223(95)00255-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Millen AE, Dodd KW, Subar AF. Use of vitamin, mineral, nonvitamin, and nonmineral supplements in the United States: the 1987, 1992, and 2000 National Health Interview Survey results. J Am Diet Assoc. 2004;104:942–950. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2004.03.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kelly JP, Kaufman DW, Kelley K, Rosenberg L, Anderson TE, Mitchell AA. Recent trends in use of herbal and other natural products. Arch Intern Med. 2005;165:281–286. doi: 10.1001/archinte.165.3.281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gugliotta G. Health concerns grow over herbal aids: as industry booms, analysis suggests rising toll in illness and death. Washington Post. 2000 March 19;:A01. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Natural Marketing Institute. The 2005 Health & Wellness Trends Report: Dietary Supplements. Harleysville, Pa: Natural Marketing Institute; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Neuhouser ML. Dietary supplement use by American women: challenges in assessing patterns of use, motives and costs. J Nutr. 2003;133:1992S–1996S. doi: 10.1093/jn/133.6.1992S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dietary Supplement Health and Education Act of 1994. Pub L No. 103–417, Stat 4325 (codified at USC §301 [1994]).

- 10.Pinn G. Adverse effects associated with herbal medicine. Aust Fam Physician. 2001;30:1070–1075. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Barnes J, Mills SY, Abbot NC, Willoughby M, Ernst E. Different standards for reporting ADRs to herbal remedies and conventional OTC medicines: face-to-face interviews with 515 users of herbal remedies. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 1998;45:496–500. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2125.1998.00715.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ko RJ. Adulterants in Asian patent medicines [letter] N Engl J Med. 1998;339:847. doi: 10.1056/nejm199809173391214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Saper RB, Kales SN, Paquin J, et al. Heavy metal content of ayurvedic herbal medicine products. JAMA. 2004;292:2868–2873. doi: 10.1001/jama.292.23.2868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Angell M, Kassirer JP. Alternative medicine—the risks of untested and unregulated remedies [editorial] N Engl J Med. 1998;339:839–841. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199809173391210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Izzo AA, Ernst E. Interactions between herbal medicines and prescribed drugs: a systematic review. Drugs. 2001;61:2163–2175. doi: 10.2165/00003495-200161150-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine. [Accessed March 28, 2007];NCCAM-funded research for FY 2004. Available at: http://nccam.nih.gov/research/extramural/awards/2004/index.htm.

- 17.Basch EM, Ulbricht CE, editors. Natural Standard Herb & Supplement Handbook: The Clinical Bottom Line. St Louis, Mo: Elsevier Mosby; 2005. [Accessed April 13, 2007]. Available at: www.naturalstandard.com. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wilkes MS, Bell RA, Kravitz RL. Direct-to-consumer prescription drug advertising: trends, impact, and implications. Health Aff (Millwood) 2000;19:110–128. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.19.2.110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Blendon RJ, DesRoches CM, Benson JM, Brodie M, Altman DE. Americans’ views on the use and regulation of dietary supplements. Arch Intern Med. 2001;161:805–810. doi: 10.1001/archinte.161.6.805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.National Center for Health Statistics. 2002 National Health Interview Survey (NHIS) Public Use Data Release. Hyattsville, Md: US Dept of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Conner M, Kirk SF, Cade JE, Barrett JH. Why do women use dietary supplements? the use of the theory of planned behaviour to explore beliefs about their use. Soc Sci Med. 2001;52:621–633. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(00)00165-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kaufman DW, Kelly JP, Rosenberg L, Anderson TE, Mitchell AA. Recent patterns of medication use in the ambulatory adult population of the United States: the Slone survey. JAMA. 2002;287:337–344. doi: 10.1001/jama.287.3.337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Perkin JE, Wilson WJ, Schuster K, Rodriguez J, Allen-Chabot A. Prevalence of nonvitamin, nonmineral supplement usage among university students. J Am Diet Assoc. 2002;102:412–414. doi: 10.1016/s0002-8223(02)90096-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Houston DK, Johnson MA, Daniel TD, Poon LW. Health and dietary characteristics of supplement users in an elderly population. Int J Vitam Nutr Res. 1997;67:183–191. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Paramore LC. Use of alternative therapies: estimates from the 1994 Robert Wood Johnson Foundation National Access to Care Survey. J Pain Symptom Manage. 1997;13:83–89. doi: 10.1016/s0885-3924(96)00299-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Astin JA. Why patients use alternative medicine: results of a national study. JAMA. 1998;279:1548–1553. doi: 10.1001/jama.279.19.1548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Martin RH. The role of nutrition and diet in rheumatoid arthritis. Proc Nutr Soc. 1998;57:231–234. doi: 10.1079/pns19980036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Conner M, Kirk SF, Cade JE, Barrett JH. Environmental influences: factors influencing a woman’s decision to use dietary supplements. J Nutr. 2003;133:1978S–1982S. doi: 10.1093/jn/133.6.1978S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Patterson RE, Neuhouser ML, White E, Hunt JR, Kristal AR. Cancer-related behavior of vitamin supplement users. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 1998;7:79–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Satia-Abouta J, Kristal AR, Patterson RE, Littman AJ, Stratton KL, White E. Dietary supplement use and medical conditions: the VITAL study. Am J Prev Med. 2003;24:43–51. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(02)00571-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dundas ML, Keller JR. Herbal, vitamin, and mineral supplement use and beliefs of university students. Top Clin Nutr. 2003;18:49–53. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Krumbach CJ, Ellis DR, Driskell JA. A report of vitamin and mineral supplement use among university athletes in a division I institution. Int J Sport Nutr. 1999;9:416–425. doi: 10.1123/ijsn.9.4.416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Honda K, Jacobson JS. Use of complementary and alternative medicine among United States adults: the influences of personality, coping strategies, and social support. Prev Med. 2005;40:46–53. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2004.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.McCann MA. Dietary supplement labeling: cognitive biases, market manipulation & consumer choice. Am J Law Med. 2005;31:215–268. doi: 10.1177/009885880503100204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Morris CA, Avorn J. Internet marketing of herbal products. JAMA. 2003;290:1505–1509. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.11.1505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Turner RB, Bauer R, Woelkart K, Hulsey TC, Gangemi JD. An evaluation of Echinacea angustifolia in experimental rhinovirus infections. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:341–348. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa044441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fennell D. Determinants of supplement usage. Prev Med. 2004;39:932–939. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2004.03.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gunther S, Patterson RE, Kristal AR, Stratton KL, White E. Demographic and health-related correlates of herbal and specialty supplement use. J Am Diet Assoc. 2004;104:27–34. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2003.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rafferty AP, McGee HB, Miller CE, Reyes M. Prevalence of complementary and alternative medicine use: state-specific estimates from the 2001 Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System. Am J Public Health. 2002;92:1598–1600. doi: 10.2105/ajph.92.10.1598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]