Abstract

Fibronectin type III (FN-III) domains are autonomously folded modules found in a variety of multidomain proteins. The 10th FN-III domain from fibronectin (fnFN10) and the 3rd FN-III domain from tenascin-C (tnFN3) have 27% sequence identity and the same overall fold; however, the CC′ loop has a different pattern of backbone hydrogen bonds and the FG loop is longer in fnFN10 compared to tnFN3. To examine the influence of length, sequence, and context in determining dynamical properties of loops, CC′ and FG loops were swapped between fnFN10 and tnFN3 to generate four mutant proteins and backbone conformational dynamics on ps-ns and μs-ms timescales were characterized by solution 15N-NMR spin relaxation spectroscopy. The grafted loops do not strongly perturb the properties of the protein scaffold; however, specific effects of the mutations are observed for amino acids that are proximal in space to the sites of mutation. The amino acid sequence primarily dictates conformational dynamics when the wild-type and grafted loop have the same length, but both sequence and context contribute to conformational dynamics when the loop lengths differ. The results suggest that changes in conformational dynamics of mutant proteins must be considered in both theoretical studies and protein design efforts.

INTRODUCTION

The conformational properties of loops are integral to protein structure and function. Loops constitute the most variable aspects of homologous proteins and frequently comprise essential elements of binding and catalytic sites. Consequently, the amplitudes and timescales of conformational dynamics of loops play important roles in ligand binding and in catalysis. Prototypical examples include antigen recognition by hypervariable loops in antibodies (1) and closure of Ω loops over active sites as part of the catalytic cycle of enzymes (2). Optimization of loop geometry is an important aspect of protein structure prediction (3). Variation of loop composition to achieve new functional properties is a successful approach in protein engineering (4). Despite the theoretical and practical importance of loop properties to protein structures and functions, few experimental studies have addressed the effect on conformational dynamics of variations in the length or sequence composition of loops.

NMR spectroscopy has emerged as a principal technique for site-resolved investigations of protein conformational dynamics on ps-ns and μs-ms timescales (5). A number of investigations of conformational dynamic properties of loops in site-directed mutant proteins have been reported (6–9). In a particularly important study, Akke and co-workers (9) investigated the backbone dynamical properties of the EF-hand calcium-binding loops in the (A14D + A15Δ + P20Δ + N21G + P43M) mutant of calbindin D9k. In this mutant, the N-terminal pseudo-EF-hand loop, characteristic of S100 proteins, is converted into a consensus EF-hand loop. Results for the calcium-free states of the wild-type and mutant proteins demonstrate that the entire N-terminal EF-hand forms a rigid structure that allows calcium binding with only minor rearrangement. Thus, the structural and dynamical properties of the entire EF-hand motif, rather than the loop sequence alone, are the major determinants of loop flexibility.

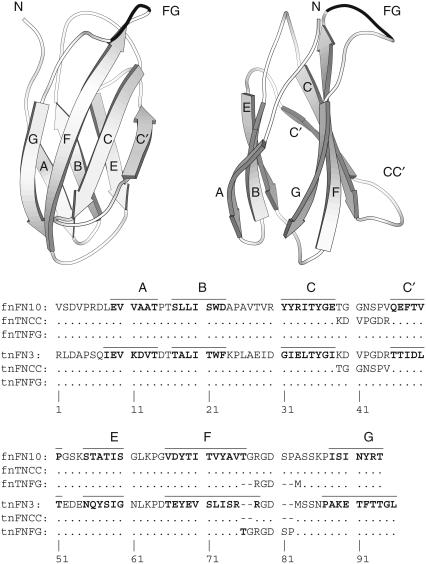

Fibronectin-III (FN-III) domains are autonomously folded modules found in a large variety of multidomain proteins. FN-III domains are classified as members of the immunoglobulin fold superfamily and are composed of seven antiparallel β-strands, denoted A, B, C, C′, E, F, and G, arranged in two sheets, as shown in Fig. 1. A subset of FN-III domains employs an Arg-Gly-Asp (RGD) tripeptide located in a surface-exposed loop between strands F and G to mediate contact with cell-surface receptors. The 10th FN-III domain from fibronectin (fnFN10) and the 3rd FN-III domain from tenascin-C (tnFN3) have 27% sequence identity (Fig. 1) and the same overall protein fold. The fnFN10 domain has a thermal denaturation midpoint of 88°C, one of the highest known for individual FN-III domains (10,11), whereas tnFN3 has a thermal denaturation midpoint of 64°C (12). Notably, fnFN10 and tnFN3 present the RGD motifs in different structural contexts. The longer FG loop in fnFN10 protrudes from the body of the protein, whereas the shorter FG loop in tnFN3 forms a tight type II′ β-turn. In addition, the CC′ loop has a different pattern of backbone hydrogen bonds and is more extended in fnFN10 compared to tnFN3. The FN-III domain has been developed as a scaffold for engineering novel binding proteins by mutagenesis of the BC and FG loops (13,14).

FIGURE 1.

Fibronectin type 10 domain structure and sequence alignments. The structural representation is drawn using Molscript (48) from the PDB file 1FNA; five N-terminal residues not present in the crystal structure have been built onto the structure (17). The sequence alignment uses the fnFN10 residue numbering; thus, two-residue gaps appear before and after the FG loop RGD sequence in tnFN3. The β-strands are indicated by bars above the fnFN10 and tnFN3 sequences and by boldfaced letters in the sequence alignment. Conserved residues in the mutant proteins are shown by dots; gaps or deletions are shown by dashes.

Backbone and side chain conformational dynamics of wild-type fnFN10 and tnFN3 domains have been investigated extensively by NMR spectroscopy (15–19). Intramolecular dynamics of the protein backbone of fnFN10 and tnFN3 have been studied by 15N-nuclear spin relaxation. The CC′ and FG loops in fnFN10 exhibit extensive flexibility on ps-ns timescales; in contrast, the CC′ and FG loops in tnFN3 are substantially more rigid on these timescales. Neither FG loop exhibits chemical exchange line broadening, reflecting motions on μs-ms timescales. The CC′ loop of fnFN10 also is devoid of chemical exchange line broadening; however, the CC′ loop of tnFN3 shows broadening at residues Asp-40 and Arg-45, which are located near the beginning and end of the loop and may constitute hinges.

Both fnFN10 and tnFN3 domains have been used for biophysical studies of folding and stability, primarily by Clarke and co-workers (10,16,20–23). Of greatest relevance to the investigation here, Cota and co-workers measured the effects on thermodynamic stability of a large number of individual point mutations, primarily in the β-strands, of fnFN10 and tnFN3 (21). Changes in free energy of folding for tnFN3 are correlated with the number of contacts lost upon mutation. In contrast, loss of free energy upon mutation is significantly lower for fnFN10, particularly mutations of residues in the A, B, and G strands. This difference together with differences in amide proton-solvent exchange rates and in side-chain mobility (16) suggest a greater degree of plasticity in the fnFN10 domain that accommodates mutations with fewer deleterious effects.

The homologous structures but distinct CC′ and FG loops in the fnFN10 and tnFN3 domains provide an opportunity to differentiate the influence of length, sequence, and context in determining dynamical properties of loops. In this study, the CC′ and FG loops were swapped to generate four mutant proteins, designated fnTNCC, fnTNFG, tnFNCC, and tnFNFG. The initial lowercase two letters indicate the scaffold, and the uppercase four letters indicate the grafted loop. Thus, fnTNCC refers to a construct consisting of the fnFN10 domain as a scaffold and the grafted tnFN3 CC′ loop. The amino acid sequences of the wild-type and mutant proteins are compared in Fig. 1. The initial studies of the wild-type tnFN3 used a 90-residue construct (17). Addition of two residues at the C-terminus increases the stability of this domain and reduces conformational dynamics on μs-ms timescales (12,16–18). Therefore, this investigation used a tnFN3 domain extended by two residues at the C-terminus for wild-type and mutant tnFN3 domains. Conformational dynamics on ps-ns and μs-ms timescales were characterized by solution 15N-NMR spin relaxation spectroscopy.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Wild-type fnFN10 and tnFN3 domains

pET-11b (Novagen, Madison, WI) plasmids coding for the wild-type fnFN10 and tnFN3 domains were a generous gift from Professor Harold Erickson (Duke University). The original construct for tnFN3 was extended by two residues (Gly-Leu) at the C-terminus by polymerase chain reaction (PCR). This construct has been shown to have improved thermodynamic properties and to exhibit reduced chemical exchange line broadening (12,18).

Construction of loop-swap mutants

Mutants were designed by using sequence alignments and structural superpositions; the grafted loop sequences are shown in Fig. 1. For the fnTNFG mutant, an additional substitution was made: Ala-83 was substituted with Met to more closely mimic the FG loop found in wild-type tnFN3. This Met is part of a type-II′ β-hairpin turn in the FG loop of tnFN3 and makes two backbone-to-backbone hydrogen bonds with the Arg-78 in the RGD motif (24). Genes for the tnFN3 and fnFN10 loop-swap mutants were synthesized using standard methods (25). Briefly, for each mutant, the N-terminal and C-terminal halves of the full-length gene were synthesized by separate PCR reactions. Primers incorporated the grafted loop sequence as necessary. A third PCR reaction was used to combine the C- and N-terminal halves and generate the full-length loop-swap mutant gene. The mutant genes were inserted into the pET-11b plasmid and transformed into the BL-21(DE3) Escherichia coli strain (Novagen) for protein overexpression.

Protein expression and purification

Overexpression and purification conditions for human tnFN3 and fnFN10 have been described elsewhere (26). Purification of the mutant domains employed the same protocol as the respective wild-type protein. Protein samples labeled with 15N and 13C/15N were expressed in M9 medium (27) containing 15NH4Cl or 15NH4Cl and 13C6 D-glucose, respectively (Cambridge Isotopes, Andover, MA). Proteins were dissolved in a 90% H2O/10% D2O buffer (10 mM NaCl, 10 mM NaCH3COOH, pH 5.5) for NMR spectroscopy. Protein concentrations were 0.8–1.3 mM for samples used for resonance assignments and 0.4–0.7 mM for samples used for relaxation experiments.

Melting temperature

Thermal unfolding was monitored by circular dichroism (CD) spectroscopy, as described previously for wild-type tnFN3 and fnFN10 domains (10,12). CD measurements were performed for 21 μM samples of fnFN10, fnTNCC, and fnTNFG (10 mM NaCH3COOH, 1 M urea, pH 5.5 buffer) on a JASCO-800 spectropolarimeter (Jasco, Tokyo, Japan) at a wavelength of 227 nm. Melting temperatures of the three FN domains were determined in the presence of 1 M urea to reduce the values of Tm for these domains. Measurements were performed for 6 μM samples of tnFN3, tnFNCC, and tnFNFG (10 mM NaCH3COOH, pH 5.5 buffer) using a JASCO-600 spectropolarimeter at a wavelength of 230 nm. The sample temperature was controlled by a Pelletier water bath, and the rate of temperature increase was 60°C/h. The Tm was taken to be the inflection point of the melting curve for each protein.

NMR spectroscopy

Sequence-specific assignments were obtained for the loop-swap mutants using standard double- and triple-resonance methods (28), as well as previously published assignments for the wild-type proteins (17). Assignment data for the FN mutants were collected at 300 K on a Varian 500 MHz spectrometer (Varian, Palo Alto, CA). Assignment data for the TN mutants were collected at 300 K on a Bruker DRX500 spectrometer (Bruker Instruments, Billerica, MA). Triple-resonance and relaxation spectra were processed using NMRPipe (29) and analyzed using the program Sparky (University of California, San Francisco). Sample temperatures were calibrated using a 100% methanol sample, and chemical shifts were referenced to an external sodium 2,2-dimethyl-2-silapentane-5-sulfonate standard (30).

Relaxation measurements

Relaxation data for all protein samples were collected at 300 K on a Bruker DRX500 spectrometer and processed as for triple-resonance data. Previously published two-dimensional sensitivity-enhanced gradient-selected pulse sequences were used to measure 15N R1, 15N R2, {1H}-15N nuclear Overhauser effect (NOE) (31,32), and ηxy (33). The R1, R2, and NOE experiments were collected with (150 × 2048) complex points and spectral widths of (2500 Hz × 12,500 Hz) in the (t1 × t2) dimensions. The ηxy experiments were collected with (128 × 2048) complex points and the same spectral widths. Spectra for six relaxation delays were recorded in duplicate for R1 and R2 experiments. R1 and R2 rate constants were determined by fitting peak heights to a single exponential decay using the in-house program Curvefit (www.palmer.hs.columbia.edu). The steady-state NOE was determined from the ratio of peak heights of consecutively measured experiments in the absence and presence of 1H saturation. NOE experiments were repeated 3–5 times with the mean value taken as the NOE and the sample deviation as the uncertainty. Five relaxation delays were used for the ηxy experiments. Signal intensity ratios from auto and crosspeaks were fit to a hyberbolic tangent using Curvefit; jackknife simulations were used to estimate uncertainties.

Structure modeling

Structural models for the mutant FN-III domains were generated using computer simulations. The grafted loops sequences were built into the wild-type structural coordinates taken from Protein Data Bank (PDB) files 1FNA for fnFN10 and 1TEN for tnFN3. The first five N-terminal residues of fnFN10 and the C-terminal two-residue extension of tnFN3 were built onto the structures using standard conformations energy minimized with a dielectric constant of 10 in the program Xplor-NIH (34). All free energy calculations were carried out using the CHARMM22 force field (35). For each mutant, 1000 random conformations of the grafted loop were generated using the program Loopy (36). Hydrogens were added to the structures, and the resulting mutant loop structures were energy minimized using Xplor-NIH. All atoms not part of the loop were held fixed during the loop optimization. Loop structures were evaluated by comparing the conformational energies of the models calculated using three terms: a free energy term that encompassed mechanical and nonbonded interactions between the atoms within the loop, a free energy term that encompassed mechanical and nonbonded interactions between the atoms of the loop and the atoms of the scaffold, and a solvation free energy term that was obtained from solutions of the finite difference Poisson-Boltzmann equation with nonpolar solvation accounted for with a surface area term (37). The conformation with the most favorable overall free energy was selected as the final structural model. In the case of the fnTNFG mutant, the grafted loop was too small to bridge the stems of the fnFN10 scaffold; consequently, residues Val-75 and Ser-84 were included as part of the loop sequence during structure prediction.

Model-free analysis

Amide backbone dynamics were characterized by fitting the relaxation parameters to one of five models using the model-free formalism (38–40). The five models are characterized according to the subset of parameters included: model 1, S2; model 2, S2, τe; model 3, S2, Rex; model 4, S2, τe, Rex; and model 5,  S2, τe in which S2 is the square of the generalized order parameter, τe is the internal correlation time,

S2, τe in which S2 is the square of the generalized order parameter, τe is the internal correlation time,  is the fast-limit order parameter in the extended model-free formalism, and Rex is a phenomenological term that describes chemical exchange. The program FAST-Modelfree (41), interfaced with Modelfree 4.01 (42), was utilized to fit motional parameters to spin-relaxation data. Model selection was based on a protocol described elsewhere (42). The rotational diffusion tensor elements were optimized using the program R2R1_diffusion (http://www.palmer.hs.columbia.edu) (43), which is based on the method of Tjandra and co-workers (44). Residues used for fitting the tensor were selected as described elsewhere (45). Diffusion tensor parameters were held fixed during the model selection process. After a model had been assigned to every spin, the model and diffusion tensor parameters were optimized simultaneously. This process was repeated until both sets of parameters converged. Model-free calculations were performed using amide bond lengths of 1.02 Å and a 15N chemical shift anisotropy of −160 ppm. Relaxation data for fnFN10 collected previously (17) were reevaluated using the above protocol. Values of Rex = R2 − κηxy also were determined from measured values of R2 and ηxy as described elsewhere (46). Average values of κ = R2/ηxy were determined empirically for each protein construct using only data for 15N spins fit with models 1 or 2 in the model-free calculations.

is the fast-limit order parameter in the extended model-free formalism, and Rex is a phenomenological term that describes chemical exchange. The program FAST-Modelfree (41), interfaced with Modelfree 4.01 (42), was utilized to fit motional parameters to spin-relaxation data. Model selection was based on a protocol described elsewhere (42). The rotational diffusion tensor elements were optimized using the program R2R1_diffusion (http://www.palmer.hs.columbia.edu) (43), which is based on the method of Tjandra and co-workers (44). Residues used for fitting the tensor were selected as described elsewhere (45). Diffusion tensor parameters were held fixed during the model selection process. After a model had been assigned to every spin, the model and diffusion tensor parameters were optimized simultaneously. This process was repeated until both sets of parameters converged. Model-free calculations were performed using amide bond lengths of 1.02 Å and a 15N chemical shift anisotropy of −160 ppm. Relaxation data for fnFN10 collected previously (17) were reevaluated using the above protocol. Values of Rex = R2 − κηxy also were determined from measured values of R2 and ηxy as described elsewhere (46). Average values of κ = R2/ηxy were determined empirically for each protein construct using only data for 15N spins fit with models 1 or 2 in the model-free calculations.

RESULTS

Thermal stability

The melting temperatures (Tm) for the two wild-type and four mutant domains were measured to assess relative stabilities of the different constructs. The values of Tm determined for wild-type tnFN3 and fnFN10 at pH 5.5 were ∼59°C and ∼75°C, respectively. These values compare well with previously determined transition midpoints of ∼64°C and ∼88°C determined at pH 5.0 (10–12). Consistent with these results, tnFN3 has been shown to be more stable at pH 5.0 than at pH 5.5 (20). The most stable of the three TN domains is wild-type tnFN3 followed by the mutant tnFNCC, which has a Tm of 54°C, and the mutant tnFNFG, which has a Tm of 45°C. The melting temperatures of the FN domains do not exhibit a similar trend; rather, all three domains have Tm ∼75°C.

Chemical shift assignments

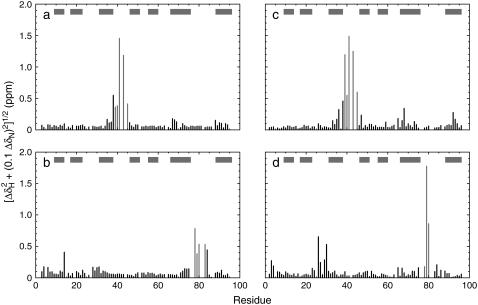

Chemical shift assignments for the mutants were performed using wild-type assignments as a guide. As shown in Fig. 2, few chemical shift changes are observed in the mutants relative to wild-type FN-III domains outside of the mutation sites or the immediately adjacent flanking regions. This observation lends strength to the assumption that structural changes due to the loop swaps are minimal, and the packing and structure of the FN-III scaffold remains fundamentally unaltered. Only residue Glu-38 in fnTNCC, which is adjacent to the mutation site, shows a shift perturbation >0.2 ppm. Residue Ser-84 in fnTNFG has ΔδH = −0.21 ppm and ΔδN = −3.7 ppm. Ser-84 is adjacent to the FG loop mutation and is involved in a hydrogen bond to the backbone of Pro-82 in the wild-type protein. The chemical shift changes observed for Ser-84 in fnTNFG are likely due to the absence of the FG-loop residue Pro-82, which disrupts an H-bond between the backbone of this residue and the Ser-84 side chain. Residue Tyr-68 in tnFNCC has ΔδH = 0.31 ppm and ΔδN = 2.2 ppm. In wild-type tnFN3, Tyr-68 is involved in stacking interactions with residues Ile-38 and Val-41 of the CC′ loop. Disruption of these stacking interactions, along with increased motility of the grafted loop (vide infra), in the tnFNCC mutant probably result in the observed shift changes observed for Tyr-68. Residues Leu-26 through Asp-30 of the BC loop in tnFNFG, which are close to the end of the F strand and beginning of the FG loop also show chemical shift perturbations. In particular, residue Leu-26 has ΔδH = −0.65 ppm and ΔδN = −0.7 ppm and residue Asp-30 has ΔδH = −0.52 ppm and ΔδN = 0.8 ppm. Because few hydrogen bonds exist between the FG loop and this group of residues in wild-type tnFN3, the grafted loop may have a subtle effect on the packing of the side chains.

FIGURE 2.

Chemical shift perturbations. The backbone chemical shift perturbation for backbone 15N and 1HN nuclei, defined by  in which ΔδX is the difference in the chemical shift of nucleus X in the mutant, and wild-type proteins are shown as a function of amino acid sequence for (a) fnTNCC, (b) fnTNFG, (c) tnFNCC, and (d) tnFNFG proteins. Data for the mutated residues are shown in gray. The locations of the β-strands from A to G are indicated by the horizontal gray bars.

in which ΔδX is the difference in the chemical shift of nucleus X in the mutant, and wild-type proteins are shown as a function of amino acid sequence for (a) fnTNCC, (b) fnTNFG, (c) tnFNCC, and (d) tnFNFG proteins. Data for the mutated residues are shown in gray. The locations of the β-strands from A to G are indicated by the horizontal gray bars.

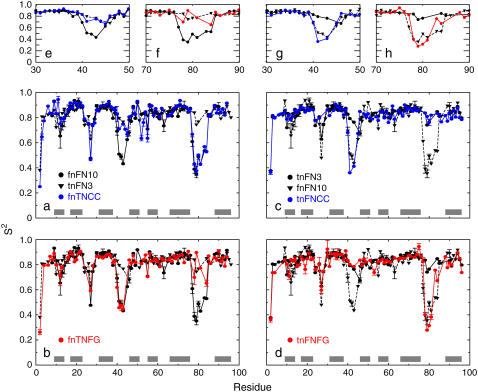

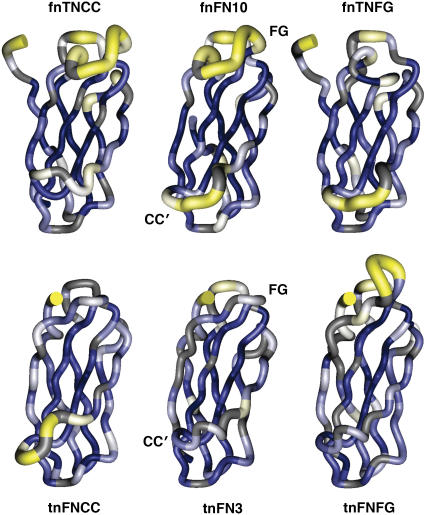

Model-free analysis

The relaxation rate data in this study were evaluated using an axially symmetric diffusion tensor. Model-free parameters for wild-type fnFN10 and tnFN3 were originally reported for calculations done using an isotropic diffusion tensor (17). Thus, for consistency, parameters for fnFN10 were recalculated with an axially symmetric diffusion tensor using the relaxation rate constants reported previously (17). Generalized order parameters calculated using the two approaches are in good agreement, but fewer residues are fit with Rex terms when utilizing an axially symmetric diffusion tensor. Parameters of the final diffusion tensors are given in Table 1. Order parameters are shown as a function of residue position in Fig. 3 and mapped onto the structures of the domains in Fig. 4. Few changes in S2 are observed for residues other than the residues of the loop grafts in the mutant domains, and most of these changes can be attributed to systematic effects on the values of S2 due to partial resonance overlap in NMR spectra. For example, the only significant difference in order parameters outside the mutation site for tnFNCC is obtained for residue Thr-46, just C-terminal to the CC′ loop. Residue Thr-46 in the tnFN3 domain has a relatively low S2 = 0.674, whereas for tnFNCC, S2 = 0.849. However, Thr-46 also has a large S2 = 0.836 in the tnFNFG mutant. Thus, the order parameter calculated for residue Thr-46 in tnFN3 is probably systematically underestimated.

TABLE 1.

Diffusion tensor parameters

| fnFN10 | fnTNCC | fnTNFG | tnFN3 | tnFNCC | tnFNGF | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| τm (ns) | 6.62 ± 0.02 | 5.79 ± 0.02 | 5.50 ± 0.02 | 5.25 ± 0.01 | 5.09 ± 0.02 | 5.61 ± 0.02 |

| D‖/D⊥ | 1.27 ± 0.03 | 1.35 ± 0.03 | 1.41 ± 0.04 | 1.47 ± 0.03 | 1.29 ± 0.05 | 1.44 ± 0.04 |

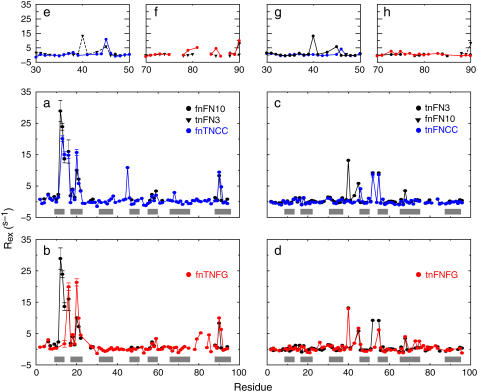

FIGURE 3.

Backbone dynamics on ps-ns timescales. Values of backbone 15N S2 for loop swap mutant proteins are compared to values for wild-type fnFN10 and tnFN3. (a) fnTNCC (blue circles and solid line) and (b) fnTNFG (red circles and solid line) are compared to wild-type fnFN10 (black circles and solid line) and wild-type tnFN3 (black triangles and dashed line). (c) tnFNCC (blue circles and solid line) and (d) tnFNFG (red circles and solid line) are compared to wild-type tnFN3 (black circles and solid line) and wild-type fnFN10 (black triangle and dashed line). Error bars similar to or smaller than the size of the plotted points are not shown. Expansions showing the site of mutation are shown: (e) fnTNCC residues 30–50, (f) fnTNFG residues 70–90, (g) tnFNCC residues 30–50, and (h) tnFNFG residues 70–90. Error bars are not shown for clarity.

FIGURE 4.

Structural dependence of backbone dynamics on ps-ns timescales. The values of S2 shown in Fig. 3 are mapped in pseudocolor onto the fnTNCC predicted structure, the fnFN10 structure, the fnTNFG predicted structure, the tnFNCC predicted structure, the tnFN3 structure, and the tnFNFG predicted structure. The location of the CC′ and FG loops are shown for the wild-type structures. The first five residues were not present in the PDB file 1FNA used to perform the data analysis for wild-type fnFN10.

Fast dynamics for fnTNCC

Values of S2 for the CC′ loop in the fnTNCC mutant are compared to wild-type fnFN10 and tnFN3 in Fig. 3, a and e. Data for residues Asp-44 and Arg-45 are missing for wild-type tnFN3. Residue Asp-44 is badly overlapped in the NMR spectra, and Arg-45 could not be fit to any one of the five motional models during model-free analysis. Arg-45 could not be fit in the tnFNFG mutant either, suggesting that the dynamical motions of this residue in the wild-type CC′ background may be too complicated to describe using the methods here. However, Val-41, Gly-43, Asp-44, and Arg-45 (residue 42 is Pro) have fairly similar values of S2 in the fnTNCC mutant, ranging between 0.67 and 0.75. Residues Lys-39, Asp-40, and Gly-43 have very similar values in wild-type tnFN3 and fnTNCC; only Val-41 is more flexible in the mutant. Residues Asp-40, Val-41, Gly-43, and Asp-44 are notably more rigid in the fnTNCC mutant than the corresponding positions in the wild-type fnFN10.

Fast dynamics for fnTNFG

Values of S2 for the FG loop in the fnTNFG mutant are compared to wild-type fnFN10 and tnFN3 in Fig. 3, b and f. Only four residues were inserted into the fnFN10 FG loop, and one of those residues, Asp-80 of the RGD motif, is overlapped in the NMR spectra of the mutant. Furthermore, residue Gly-79 has an unusually large S2 for a glycine in a loop (S2 = 0.90). Gly-79 was fit to model 2, without an Rex contribution; and model 3 gives a large value of the fitting residuals (Γ = 42.9) in the model-free analysis. However, a substantial exchange term is measured for Gly-79 (Rex = 3.3 s−1) using the Hahn-echo experiments. Thus, this value of S2 may be systematically biased. Residues Arg-78 and Ser-84 in the FG loop have values of S2 intermediate between values observed for the more flexible fnFN10 and more rigid tnFN3 domains. Interestingly, S2 for Ser-84 has nearly the same value in the fnTNFG (0.65) and tnFNFG (0.67) mutants (vide infra). More changes in S2 are observed outside the mutated loop of fnTNFG than are observed for any other mutant. Most of the differences can be explained by the proximity of these residues to the mutated loop region. For example, Val-27 in the BC loop has an increased S2 in the mutant, suggesting that increased rigidity of the grafted FG loop has an effect on conformational properties in the flanking BC loop.

Fast dynamics for tnFNCC

Values of S2 for the CC′ loop in the tnFNCC mutant are compared to wild-type fnFN10 and tnFN3 in Fig. 3, c and g. Residue Gly-41 at the apex of the loop has a lower value of S2 in tnFNCC (0.36) than in wild-type fnFN10 (0.51) or tnFN3 (0.79). Data for Asn-42 could not be fit to any of the five models during the model-free analysis; however this polar residue is at the apex of the loop and probably is at least as flexible as the neighboring residues. The values of S2 for other residues in the CC′ loop in the mutant are very similar to the values for wild-type fnFN10 and much lower than for wild-type tnFN3.

Fast dynamics for tnFNFG

Values of S2 for the FG loop in the tnFNFG mutant are compared to wild-type fnFN10 and tnFN3 in Figs. 3, d and h. The properties of this mutant are the most complex. Residues in the apex of the loop (Gly-79, Asp-80, and Ser-81) have lower values of S2 than wild-type fnFN10. In contrast, flanking residues, notably Gly-77, Met-83, and Ser-84, show increased rigidity compared to fnFN10. Met-83 and Ser-84 are part of a short stretch of β-strand in the G strand of tnFN3 but are still part of the FG loop in fnFN10. As described above, the value of S2 for Ser-84 is very similar in fnTNFG and tnFNFG and intermediate between the values for the wild-type FN-III domains.

Chemical exchange broadening

Values of Rex were determined both from the model-free analysis for residues fit with models 3 or 4 and from Hahn-echo and relaxation-interference experiments for all residues in fnTNCC, fnTNFG, tnFN3, tnFNCC, and tnFNFG; values of Rex for fnFN10 were determined from the model-free analysis for residues fit with models 3 or 4. Results are shown as a function of residue position in Fig. 5. Comparisons of the exchange rates determined from model-free calculations and the Hahn-echo experiments show very good correlation between the two sets of parameters. Few significant differences were observed for any of the domains for Rex > 1 s−1. For tnFN3 and tnFNFG, model-free calculations for residue Arg-45 do not converge for any model; however, the Hahn-echo experiments predict an exchange term of 5.8 s−1. For the fnTNFG domain, model-free calculations do not predict a model that contains an Rex term for residue Gly-79, but a value of 3.3 s−1 is calculated from the Hahn-echo experiments. Given the large rates obtained from the Hahn echo experiments, these residues probably are subject to exchange and the model-free analysis has selected an inappropriate model. The preservation of chemical exchange behavior between the mutant and wild-type FN-III domains outside the sites of mutation suggests that the grafted loops have not resulted in global changes to the protein scaffold.

FIGURE 5.

Backbone dynamics on μs-ms timescales. Values of Rex for loop swap mutant proteins are compared to values for wild-type fnFN10 and tnFN3. (a) fnTNCC (blue circles and solid line) and (b) fnTNFG (red circles and solid line) are compared to wild-type fnFN10 (black circles and solid line). (c) tnFNCC (blue circles and solid line) and (d) tnFNFG (red circles and solid line) are compared to wild-type tnFN3 (black circles and solid line). Error bars similar to or smaller than the size of the plotted points are not shown. Expansions showing the site of mutation are shown: (e) fnTNCC residues 30–50, (f) fnTNFG residues 70–90, (g) tnFNCC residues 30–50, and (h) tnFNFG residues 70–90. In (e and f) Rex for wild-type tnFN3 is depicted using black triangles and dashed line. (g and h) Rex for wild-type fnFN10 is depicted using black triangles and dashed line.

Slow dynamics in fnTNCC

Values of Rex for the CC′ loop in the fnTNCC mutant are compared to wild-type fnFN10 and tnFN3 in Fig. 5, a and e. Chemical exchange is observed in fnTNCC but not fnFN10 for residues Asp-40 and Arg-45 of the CC′ loop, Glu-38 of the C strand, and Tyr-68 of the F strand. Residues Asp-40, Arg-45, and Tyr-68 display exchange in the wild-type tnFN3 domain. Thus, the pattern of Rex in the CC′ loop of tnFN3 is maintained in the new environment. Residue Arg-45 has a value of Rex that is almost twice that observed in tnFN3, and Asp-40 is so broadened that it is too weak to be observed in the relaxation interference experiment but has a value of Rex = 36.9 ± 3.1 s−1 calculated from model-free results.

Slow dynamics in fnTNFG

Values of Rex for the FG loop in the fnTNFG mutant are compared to wild-type fnFN10 and tnFN3 in Fig. 5, b and f. The grafted loop clearly has affected exchange broadening for residues in the A-B-E β-sheet compared with fnFN10. Chemical exchange broadening for residues in β-strands may reflect indirect influences of other dynamical processes that alter the local magnetic environments of these residues, rather than conformational transitions of the sheet itself. Exchange in the fnTNFG mutant also is observed at sites Gly-79, Met-81, and Ser-85 in the FG loop. These residues do not display exchange broadening in the wild-type tnFN3 or fnFN10 domains; consequently, exchange at these sites is the result of the mutation and is behavior unique to fnTNFG.

Slow dynamics in tnFNCC

Values of Rex for the CC′ loop in the tnFNCC mutant are compared to wild-type fnFN10 and tnFN3 in Fig. 5, c and g. Changes observed in chemical exchange are restricted to residues of or near to the grafted CC′ loop mutation. Residue Thr-46, for instance, just C-terminal to the grafted CC′ loop, is subject to exchange in tnFNCC but not in tnFN3. In addition, exchange is eliminated for residues Gly-40 and Val-45 in the CC′ loop and Tyr-68, close to the CC′ loop in the overall structure.

Slow dynamics in tnFNFG

Values of Rex for the FG loop in the tnFNFG mutant are compared to wild-type fnFN10 and tnFN3 in Fig. 5, d and h. Additional Rex contributions are observed for residue Leu-26, which is close in the three-dimensional structure to the mutant FG loop, as well as for residues Ile-73 and Arg-75. Exchange broadening of Ile-73 and Arg-75 potentially results from disruption of the small, four residue β-sheet (Arg-75, Thr-76, Met-83, and Ser-85) seen in the crystal structure of tnFN3 but not fnFN10 (24).

DISCUSSION

Using NMR spin relaxation spectroscopy, the conformational dynamics of four loop swap mutants, representing pairwise swaps of the CC′ and FG loop sequences of fnFN10 and tnFN3 FN-III domains, have been extensively characterized and compared to the corresponding properties of the wild-type proteins. The data for the loop swap mutants presented in this work suggest that the grafted loops leave the overall structures and dynamics of the domains largely unperturbed. Importantly, no large changes in conformational dynamics were observed outside the mutation sites that could not be explained by proximity to the grafted loop; thus, the grafted loops do not significantly perturb the underlying fnFN10 or tnFN3 scaffolds.

The grafted CC′ loops have identical lengths but differ in sequence. The conformational dynamic properties of these loops are largely determined by the loop sequence, rather than the structural context of the scaffold. The S2 values of the CC′ loop sequence in tnFNCC more closely mimic the dynamics of the CC′ loop in fnFN10 than those of the equivalent positions in tnFN3, and the same is true for the reverse mutant, fnTNCC (Figs. 3 and 4). The sequence-dependent preservation of the dynamics is observed even more dramatically on the slower timescale. Wild-type chemical exchange is preserved in the CC′ loop of tnFN3 when it is grafted into the fnFN10 environment (Fig. 5). The chemical shift perturbations (Fig. 2, a and c) show that the effects of mutations largely are confined to the grafted loops themselves, further suggesting that the scaffold does not strongly influence loop properties. Inherent differences in conformational flexibility for the CC′ loops of fnFN10 and tnFN3 have been discussed previously (17). The two adjacent glycines (Gly-40 and Gly-41) located at the beginning of the CC loop in fnFN10 and the smaller average side-chain volume for residues in this loop (∼40 Å3) compared to the CC′ loop of tnFN3 (∼60 Å3) potentially contribute to conformational freedom. Furthermore, the CC′ loop in tnFN3 contains two main chain hydrogen bonds (Val-41–Ile-38 and Asp-44–Val-41) that may serve to restrict conformational mobility. Nonetheless, some effects of the scaffold environment are discernable. For example, the CC′ loop clearly affects the Fnfn10 scaffold by inducing chemical exchange in residue Tyr-68, a conserved residue that is subject to exchange in tnFN3 but not in fnFN10. The exchange observed for Tyr-68 is a result of the proximity of this residue to the CC′ loop sequence of tnFN3. Exchange is not observed at this residue in the fnFN10 domain, and exchange is eliminated in the tnFN3 domain when the CC′ loop is replaced with the equivalent residues from fnFN10.

The grafted FG loops have different lengths, and the patterns of conformational dynamics in the fnTNFG and tnFNFG mutants are complex. Order parameters in the FG loop of fnTNFG are intermediate between the low values observed in wild-type fnFN10 and high values observed in wild-type tnFN3 (Figs. 3 and 4). In addition, increased conformational exchange is observed for residues in the FG loop in the fnTNFG loop but is absent in both of the wild-type domains (Fig. 5). The increased rigidity of the FG loop in the fnTNFG mutant appears to be propagated to the flanking BC loop, as evidenced by the increased S2 for residue Val-27. The leading and trailing stems of the FG loop are more rigid in tnFNFG than in wild-type fnFN10; however, the apex of the loop is more flexible in the mutant. In particular, the similar values of S2 obtained for Ser-84 in the fnTNFG and tnFNFG mutants suggest that the intrinsic conformational properties of the loop and the intrinsic conformational properties of the scaffold provide opposing influences on the observed conformational properties for this reside. Residue Ser-84 is part of the G strand in tnFN3, but the equivalent positions in fnFN10 is still part of the FG loop (24,47). Chemical exchange is observed in residues Ile-73 and Arg-75 of tnFNFG but not at the equivalent sites in tnFN3 (Fig. 5). These residues are opposite Met-83 and Ser-84 in the structure, and exchange broadening might reflect indirect effects of conformational transitions of Met-83 and Ser-84 between sheet and nonsheet conformations.

The loop swap mutations have distinct effects on the thermal stabilities of the fibronectin and tenascin mutants. The tnFNCC and tnFNFG mutants have reduced stabilities, as measured by CD spectroscopy, compared to wild-type tnFN3. The tnFNFG mutant, in which the grafted loop is both more flexible and longer than the wild-type FG loop in tnFN3, has the lowest Tm; however, tnFNFG is still folded at 300 K and the cooperativity of unfolding is maintained (data not shown). These results indicate that the introduction of the more flexible loops from fnFN10 destabilizes the tnFN3 scaffold, perhaps because the ordered loops in wild-type tnFN3 reduce fraying of the β-strands. The similar stabilities of the wild-type fnFN10, mutant fnTNCC, and mutant fnTNFG domains indicated that the introduction of shorter, more highly ordered loops from tnFN3 has little effect on overall domain stability. These results suggest that the core β-strands in the fibronectin scaffold already are highly stabilized to compensate for the flexibility of the wild-type fnFN10 loops. These findings also support the previous suggestion by Cota et al. that the fnFN10 domain is more tolerant to the effects of mutations than the tnFN3 domain (21).

In summary, three main conclusions emerge from this investigation of the CC′ and FG loop swap mutants of fnFN10 and tnFN3: 1) the grafted loops do not strongly perturb the properties of the protein scaffold, 2) specific effects of the mutations are observed for amino acids that are proximal in space to the sites of mutation, and 3) the amino acid sequence appears to primarily dictate the conformational dynamics of the loops when the wild-type and grafted loop have the same length, but both sequence and context contribute to the resultant conformational dynamics when the loop lengths differ. The results suggest that changes in conformational dynamics, as well as structure, may contribute to altered functional properties of mutant proteins and will need to be considered in both theoretical studies and protein design efforts.

Acknowledgments

We thank Barry Honig (Columbia University) for helpful discussions and support throughout this project. We also thank Dinshaw Patel and Ananya Majumdar (Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Foundation) for providing access to the Varian 500 MHz spectrometer and assisting with experiments.

Financial support from National Institutes of Health grants GM008281 (K.F.S.), GM30518 (B.H.), and GM50291 (A.G.P.) is acknowledged gratefully.

Keri Siggers's present address is Division of Infectious Diseases, Massachusetts General Hospital, 65 Landsdowne St., Cambridge, MA 02139.

Editor: Lukas K. Tamm.

References

- 1.James, L. C., P. Roversi, and D. S. Tawfik. 2003. Antibody multispecificity mediated by conformational diversity. Science. 299:1362–1367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Boyd, A. E., C. S. Dunlop, L. Wong, Z. Radic, P. Taylor, and D. A. Johnson. 2004. Nanosecond dynamics of acetylcholinesterase near the active center gorge. J. Biol. Chem. 279:26612–26618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Petrey, D., and B. Honig. 2005. Protein structure prediction: inroads to biology. Mol. Cell. 20:811–819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Binz, H. K., and A. Pluckthun. 2005. Engineered proteins as specific binding reagents. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 16:459–469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Palmer, A. G. 2004. NMR characterization of the dynamics of biomacromolecules. Chem. Rev. 104:3623–3640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cai, M., Y.-X. Gong, L. Wen, and R. Krishnamoorthi. 2002. Correlation of binding-loop internal dynamics with stability and function in potato I inhibitor family: relative contributions of Arg50 and Arg52 in Cucurbita maxima trypsin inhibitor-V as studied by site-directed mutagenesis and NMR spectroscopy. Biochemistry. 41:9572–9579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Japelj, B., J. P. Waltho, and R. Jerala. 2004. Comparison of backbone dynamics of monomeric and domain-swapped stefin A. Proteins 54:500–512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yan, H., and X. Liao. 2003. Amino acid substitutions in a long flexible sequence influence thermodynamics and internal dynamic properties of winged helix protein genesis and its DNA complex. Biophys. J. 85:3248–3254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Malmendal, A., G. Carlstrom, C. Hambraeus, T. Drakenberg, S. Forsen, and M. Akke. 1998. Sequence and context dependence of EF-hand loop dynamics. An 15N relaxation study of a calcium-binding site mutant of calbindin D9k. Biochemistry. 37:2586–2595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cota, E., and J. Clarke. 2000. Folding of beta-sandwich proteins: three-state transition of a fibronectin type III module. Protein Sci. 9:112–120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Litvinovich, S. V., and K. C. Ingham. 1995. Interactions between type III domains in the 110 kDa cell-binding fragment of fibronectin. J. Mol. Biol. 248:611–626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hamill, S. J., A. E. Meekhof, and J. Clarke. 1998. The effect of boundary selection on the stability and folding of the third fibronectin type III domain from human tenascin. Biochemistry. 37:8071–8079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Batori, V., A. Koide, and S. Koide. 2002. Exploring the potential of the monobody scaffold: effects of loop elongation on the stability of a fibronectin type III domain. Protein Eng. 15:1015–1020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Koide, A., C. W. Bailey, X. Huang, and S. Koide. 1998. The fibronectin type III domain as a scaffold for novel binding proteins. J. Mol. Biol. 284:1141–1151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Akke, M., J. Liu, J. Cavanagh, H. P. Erickson, and A. G. Palmer. 1998. Pervasive conformational fluctuations on microsecond time scales in a fibronectin type III domain. Nat. Struct. Biol. 5:55–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Best, R. B., T. J. Rutherford, S. M. Freund, and J. Clarke. 2004. Hydrophobic core fluidity of homologous protein domains: relation of side-chain dynamics to core composition and packing. Biochemistry. 43:1145–1155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Carr, P. A., H. P. Erickson, and A. G. Palmer. 1997. Backbone dynamics of homologous fibronectin type III cell adhesion domains from fibronectin and tenascin. Structure. 5:949–959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Meekhof, A. E., S. J. Hamill, V. L. Arcus, J. Clarke, and S. M. Freund. 1998. The dependence of chemical exchange on boundary selection in a fibronectin type III domain from human tenascin. J. Mol. Biol. 282:181–194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Meekhof, A. E., and S. M. Freund. 1999. Separating the contributions to 15N transverse relaxation in a fibronectin type III domain. J. Biomol. NMR. 14:13–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Clarke, J., S. J. Hamill, and C. M. Johnson. 1997. Folding and stability of a fibronectin type III domain of human tenascin. J. Mol. Biol. 270:771–778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cota, E., S. J. Hamill, S. B. Fowler, and J. Clarke. 2000. Two proteins with the same structure respond very differently to mutation: the role of plasticity in protein stability. J. Mol. Biol. 302:713–725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cota, E., A. Steward, S. B. Fowler, and J. Clarke. 2001. The folding nucleus of a fibronectin type III domain is composed of core residues of the immunoglobulin-like fold. J. Mol. Biol. 305:1185–1194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hamill, S. J., A. Steward, and J. Clarke. 2000. The folding of an immunoglobulin-like Greek key protein is defined by a common-core nucleus and regions constrained by topology. J. Mol. Biol. 297:165–178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Leahy, D., W. A. Hendrickson, I. Aukhil, and H. P. Erickson. 1992. Structure of a fibronectin type III domain from tenascin phased by MAD analysis of the selenomethionyl protein. Science. 258:987–991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ausubel, F. M., R. Brent, R. E. Kingston, D. D. Moore, J. G. Seidman, J. A. Smith, and K. Struhl, editors. 2005. Current Protocols in Molecular Biology. John Wiley & Sons, New York.

- 26.Aukhil, I., P. Joshi, Y. Yan, and H. P. Erickson. 1993. Cell- and heparin-binding domains of the hexabrachion arm identified by tenascin expression proteins. J. Biol. Chem. 268:2542–2553. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Maniatis, T., E. F. Fritsch, and J. Sambrook. 1982. Molecular Cloning: A Laboratory Manual. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY.

- 28.Cavanagh, J., W. J. Fairbrother, A. G. Palmer, and N. J. Skelton. 1996. Protein NMR Spectroscopy: Principles and Practice. Academic Press, San Diego.

- 29.Delaglio, F., S. Grzesiak, G. Vuister, G. Zhu, J. Pfeifer, and A. Bax. 1995. NMRPipe: a multidimensional spectral processing system based on UNIX pipes. J. Biomol. NMR. 6:277–293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wishart, D. S., C. G. Bigam, J. Yao, F. Abildgaard, H. J. Dyson, E. Oldfield, J. L. Markley, and B. D. Sykes. 1995. 1H, 13C and 15N chemical shift referencing in biomolecular NMR. J. Biomol. NMR. 6:135–140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Farrow, N. A., R. Muhandiram, A. U. Singer, S. M. Pascal, C. M. Kay, G. Gish, S. E. Shoelson, T. Pawson, J. D. Forman-Kay, and L. E. Kay. 1994. Backbone dynamics of a free and a phosphopeptide-complexed Src homology 2 domain studied by 15N NMR relaxation. Biochemistry. 33:5984–6003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kay, L. E., D. A. Torchia, and A. Bax. 1989. Backbone dynamics of proteins as studied by nitrogen-15 inverse detected heteronuclear NMR spectroscopy: application to staphylococcal nuclease. Biochemistry. 28:8972–8979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kroenke, C. D., J. P. Loria, L. K. Lee, M. Rance, and A. G. Palmer. 1998. Longitudinal and transverse 1H-15N dipolar/15N chemical shift anisotropy relaxation interference: unambiguous determination of rotational diffusion tensors and chemical exchange effects in biological macromolecules. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 120:7905–7915. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schweiters, C. D., J. J. Kuszewski, N. Tjandra, and G. M. Clore. 2003. The Xplor-NIH NMR molecular structure determination package. J. Magn. Reson. 160:65–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Brooks, B. R., R. E. Bruccoleri, B. D. Olafson, D. J. States, S. Swaminathan, and M. Karplus. 1983. CHARMM: a program for macromolecular energy, minimization, and dynamics calculations. J. Comput. Chem. 4:187–217. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Xiang, Z., C. S. Soto, and B. Honig. 2002. Evaluating conformational free energies: the colony energy and its application to the problem of loop prediction. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 99:7432–7437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Smith, K. C., and B. Honig. 1994. Evaluation of the conformational free energies of loops in proteins. Proteins. 18:119–132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Clore, G. M., A. Szabo, A. Bax, L. E. Kay, P. C. Driscoll, and A. M. Gronenborn. 1990. Deviations from the simple two-parameter model-free approach to the interpretation of nitrogen-15 nuclear magnetic relaxation of proteins. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 112:4989–4991. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lipari, G., and A. Szabo. 1982. Model-free approach to the interpretation of nuclear magnetic resonance relaxation in macromolecules. 1. Theory and range of validity. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 104:4546–4559. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lipari, G., and A. Szabo. 1982. Model-free approach to the interpretation of nuclear magnetic resonance relaxation in macromolecules. 2. Analysis of experimental results. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 104:4559–4570. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cole, R., and J. P. Loria. 2003. FAST-Modelfree: a program for rapid automated analysis of solution NMR spin-relaxation data. J. Biomol. NMR. 26:203–213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mandel, A. M., M. Akke, and A. G. Palmer. 1995. Backbone dynamics of Escherichia coli ribonuclease HI: correlations with structure and function in an active enzyme. J. Mol. Biol. 246:144–163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lee, L. K., M. Rance, W. J. Chazin, and A. G. Palmer. 1997. Rotational diffusion anisotropy of proteins from simultaneous analysis of 15N and 13Ca nuclear spin relaxation. J. Biomol. NMR. 9:287–298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tjandra, N., S. E. Feller, R. W. Pastor, and A. Bax. 1995. Rotational diffusion anisotropy of human ubiquitin from 15N NMR relaxation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 117:12562–12566. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pawley, N. H., C. Wang, S. Koide, and L. K. Nicholson. 2001. An improved method for distinguishing between anisotropic tumbling and chemical exchange in analysis of 15N relaxation parameters. J. Biomol. NMR. 20:149–165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wang, C., M. J. Grey, and A. G. Palmer. 2001. CPMG sequences with enhanced sensitivity to chemical exchange. J. Biomol. NMR. 21:361–366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Main, A. L., T. S. Harvey, M. Baron, J. Boyd, and I. D. Campbell. 1992. The three-dimensional structure of the tenth type III module of fibronectin: an insight into RGD-mediated interactions. Cell. 71:671–678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kraulis, P. 1991. MOLSCRIPT: a program to produce both detailed and schematic plots of protein structures. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 24:946–950. [Google Scholar]