Abstract

Fossil fuel combustion and agriculture result in atmospheric deposition of 0.8 Tmol/yr reactive sulfur and 2.7 Tmol/yr nitrogen to the coastal and open ocean near major source regions in North America, Europe, and South and East Asia. Atmospheric inputs of dissociation products of strong acids (HNO3 and H2SO4) and bases (NH3) alter surface seawater alkalinity, pH, and inorganic carbon storage. We quantify the biogeochemical impacts by using atmosphere and ocean models. The direct acid/base flux to the ocean is predominately acidic (reducing total alkalinity) in the temperate Northern Hemisphere and alkaline in the tropics because of ammonia inputs. However, because most of the excess ammonia is nitrified to nitrate (NO3−) in the upper ocean, the effective net atmospheric input is acidic almost everywhere. The decrease in surface alkalinity drives a net air–sea efflux of CO2, reducing surface dissolved inorganic carbon (DIC); the alkalinity and DIC changes mostly offset each other, and the decline in surface pH is small. Additional impacts arise from nitrogen fertilization, leading to elevated primary production and biological DIC drawdown that reverses in some places the sign of the surface pH and air–sea CO2 flux perturbations. On a global scale, the alterations in surface water chemistry from anthropogenic nitrogen and sulfur deposition are a few percent of the acidification and DIC increases due to the oceanic uptake of anthropogenic CO2. However, the impacts are more substantial in coastal waters, where the ecosystem responses to ocean acidification could have the most severe implications for mankind.

Keywords: alkalinity, biogeochemistry, global change, ocean chemistry, nutrient eutrophication

Humans are dramatically altering the global nitrogen and sulfur budgets, with one result being the release of large fluxes of nitrogen oxides (NOx, ≈2 Tmol/yr), ammonia (NH3, ≈4 Tmol/yr), and sulfur dioxide (SO2, ≈2 Tmol/yr) to the atmosphere (1). Globally, fossil fuel combustion and biomass burning fluxes of NOx exceed the natural fluxes from land to the atmosphere (2); NH3 fluxes to the atmosphere are overwhelmed by those from human activities, mainly livestock husbandry (3); and oxidized sulfur fluxes from land are ≈10 times the natural fluxes, again because of combustion of fossil fuels and biomass burning (2). After chemical transformations in the atmosphere, much of the anthropogenic nitrogen and sulfur is deposited to the surface as the dissociation products of nitric acid (HNO3) and sulfuric acid (H2SO4). HNO3 and H2SO4 are strong acids that completely dissociate in water:

Because of the relatively short lifetime of reactive nitrogen and sulfur species in the atmosphere (days to about a week), the majority of the acid deposition occurs on land, in the coastal ocean, and in the open ocean downwind of the primary source regions in eastern North America, Europe, and South and East Asia (4–7). The subsequent acidification of terrestrial and freshwater ecosystems by dry deposition and more acidic rainfall is a well known environmental problem (8–11).

Anthropogenic nitrogen and sulfur deposition to the ocean surface alters surface seawater chemistry, leading to acidification and reduced total alkalinity. Lower pH and resulting lower CO32™ concentrations are of particular concern for a range of benthic and pelagic organisms that form calcareous (CaCO3) shells (e.g., corals, coralline algae, foraminifera, pteropods, and coccolithophores) (12, 13). The acidification effects, although not as large globally as those of anthropogenic CO2 uptake (14, 15), could be significant in coastal ocean regions because these regions are already vulnerable to other human impacts, including nutrient fertilization (15, 16), pollution, overfishing, and climate change. Here we compute bounds on the potential impact of anthropogenic nitrogen and sulfur deposition on seawater chemistry, using simulated atmospheric deposition fields applied to a coupled 3D ocean ecosystem–biogeochemical model (see Methods). We also compare these model results with field observations for U.S. coastal regions.

Basic Principles of the Effects of Atmospheric C, N, and S Deposition on Seawater Chemistry.

It is useful to frame the impact of anthropogenic nitrogen and sulfur inputs in terms of the changes in surface water dissolved inorganic carbon (DIC) and total alkalinity (Alk). DIC and Alk are conservative quantities with respect to mixing and temperature and pressure changes and, together with temperature and salinity, determine seawater pH and the partial pressure of carbon dioxide, pCO2 (17), an important factor driving air–sea CO2 exchange. Processes that increase DIC or decrease Alk lower seawater pH (ocean acidification) and raise pCO2.

CO2 combines with water to form carbonic acid (H2CO3), which then undergoes a series of acid/base dissociation reactions:

DIC concentration ([DIC]; μmol/kg) is

Anthropogenic CO2 uptake increases surface [DIC] and lowers pH (14, 18).

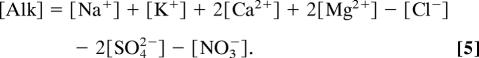

Total alkalinity ([Alk]; μeq/kg), a measure of the acid/base balance of the fluid (19), is defined conventionally as the excess of proton acceptors (bases formed from weak acids) over proton donors relative to a reference point (formally, acid dissociation pKa = 4.5; approximately the H2CO3 equivalence point):

or, alternatively, as the net positive charge from strong mineral bases minus strong mineral acids (20):

|

In Eq. 4, we neglect for clarity terms from other weak acids in seawater, such as B(OH)3, H2SiO3, and H2PO4−, which are included in our seawater thermodynamics code (21).

Atmospheric C, N, and S inputs can be converted into fluxes of inorganic carbon, fDIC (mol·m−2·y−1), and alkalinity, fAlk (eq·m−2·y−1). The fDIC flux

|

is governed by CO2 air–sea gas exchange fCO2gas, net respiration of atmospheric dissolved and particulate organic matter inputs fCorganic, and net dissolution of CaCO3 from atmospheric dust deposition fCaCO3, as well as by dissolution of DIC in rainwater fDICrain, a small term that is usually neglected. The anthropogenic changes in fCorganic and fCaCO3 are not well characterized and are not considered further here.

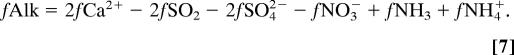

The chemical forms of the atmospheric C, N, and S inputs are important for determining their impact on the alkalinity flux:

Dissolution of calcareous mineral dust, CaCO3, in rainwater, denoted by the input of dissolved Ca2+ ion in Eq. 7, acts to add alkalinity to the surface ocean (fAlk > 0). Note the factor of 2 conversion for alkalinity, reflecting the charge on Ca2+ and CO32™ (Eqs. 4 and 5). Air–sea CO2 gas exchange, the pathway for almost all anthropogenic carbon input to the ocean, does not enter Eq. 7 because adding CO2 does not alter ocean total alkalinity (Eq. 4) but does change carbonate alkalinity (Alkcarb = [HCO3−] + 2[CO32™]) (22). Similarly, the release of CO2 from organic carbon respiration does not affect alkalinity except through related conversion of organic nitrogen (and to an even smaller extent phosphorus) to inorganic form.

Inorganic sulfur deposition adds acidity to the surface ocean (fAlk < 0), reducing surface water alkalinity. About 40–80% of atmospheric S is oxidized to H2SO4 by gas-phase and aqueous reactions and deposited to the surface by wet (dominant) and dry processes. An input of 1 mole SO42− is equivalent to −2 equivalents Alk. The remaining sulfur emissions are dry-deposited as SO2. We assume for surface seawater that all of the SO2 combines with water to form H2SO4 and thus has a similar effect on alkalinity as SO42− deposition.

Atmospheric nitrogen deposition can add either acidity or alkalinity, depending on the chemical form. The wet deposition of NO3− is acidic, and the dry deposition of NH3 is alkaline (Eqs. 4 and 5). From Eq. 4, one might expect that wet deposition of the ammonium ion NH4+ should result in no change in alkalinity because the protonated species is the primary form at the CO2 equivalence pH (pKa of NH4+ for seawater ≈9.5). However, in rainwater the main proton source for forming the ammonium ion is water, and the resulting release of OH− increases alkalinity similar to NH3 deposition. A fraction of the atmospheric N and S is deposited as ammonia–sulfate aerosols, (NH4)2SO4 and (NH4)HSO4; in our calculations we assume that the aerosols dissociate in surface seawater and include the aerosol N and S in the NH4+ and SO42− fluxes. Our alkalinity flux (Eq. 7) is similar to the atmosphere acidity equation for wet deposition from ref. 6, although of course with opposite signs. One difference is that we include additional SO2 and NH3 terms because of dry deposition.

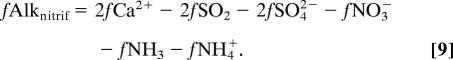

The impact of atmospheric NH4+ + NH3 input on ocean alkalinity depends on the extent to which the NH4+ is converted to NO3− by nitrification:

|

Note that almost all of the deposited NH3 will be converted to NH4+ at seawater pH. Nitrification reduces alkalinity by 2 equivalents for every mole of NH4+ consumed. Assuming complete nitrification changes the alkaline NH3 and NH4+ flux to an effective acidity flux:

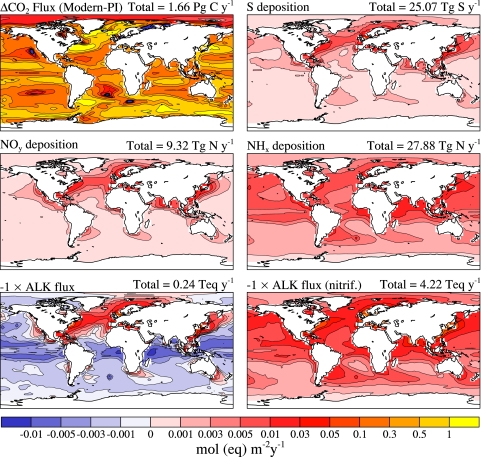

As shown below in our 3D ocean simulations, Eq. 9 is a good approximation when examining ocean alkalinity inventory changes because ≈98% of anthropogenic NH3 + NH4+ deposition is nitrified to NO3−. When referring to atmospheric precipitation, the inclusion of nitrification is often termed potential acidity (19). For the spatial flux maps below (Fig. 1), we compute both fAlk and fAlknitrif.

Fig. 1.

Model-estimated anthropogenic (1990–2000 minus preindustrial) atmospheric deposition fluxes for carbon, nitrogen, and sulfur (mol·m−2·y−1); alkalinity; and potential alkalinity, assuming complete nitrification of NH4+ + NH3 (eq·m−2·y−1).

Results and Discussion

Model atmospheric nitrogen, sulfur, and alkalinity deposition fields are computed based on estimated changes in climate and emissions between the preindustrial and current climates (1990–2000) (Fig. 1) (see Methods). The global Community Climate System Model 3 (CCSM-3) nitrogen and sulfur deposition fluxes (Table 1) are similar to the results reported in the 2001 Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change report (1, 23). For comparison, air–sea CO2 fluxes are reported from the CCSM-3 ocean model.

Table 1.

Model-estimated anthropogenic (1990–2000 minus preindustrial) and preindustrial atmospheric deposition fluxes

| Flux | Integrated anthropogenic deposition,Tmol/y or Teq/y (preindustrial) |

Anthropogenic coastal ocean flux, mol or eq·m−2·y−1 |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Global | Ocean-only | Model | Observed | |

| fCO2 | — | 138 | 0.10 to 2.00 | |

| f NH4+ + f NH3 | 4.11 (0.00) | 1.99 (0.00) | 0.00 to 0.03 | 0.02 |

| f NO3− | 1.84 (1.18) | 0.67 (0.73) | 0.00 to 0.03 | 0.02 |

| f SO42− + f SO2 | 2.21 (0.58) | 0.78 (0.49) | 0.00 to 0.03 | 0.01 |

| fAlk | −2.15 (−2.34) | −0.24 (−1.71) | −0.01 to +0.01 | |

| fAlknitrif | −10.37 (−2.34) | −4.22 (−1.71) | −0.01 to −0.10 | |

About one-third of anthropogenic NOx and SOx emissions, mostly from fossil fuel combustion, are deposited to the ocean. Because of the short atmospheric residence time, deposition is concentrated downwind of the emission sources, mostly in the temperate North Atlantic, temperate and eastern subtropical North Pacific, and northern Indian Ocean, with maximum values approaching −0.03 mol·m−2·y−1. Approximately half of agricultural NHx emissions are deposited to the ocean and are more evenly spread over the Northern Hemisphere.

The anthropogenic alkalinity flux fAlk is negative (acidic) in the temperate regions of the Northern Hemisphere dominated by fossil fuel f SO42− + f SO2 and f NO3− deposition and is positive (alkaline) in the tropics owing to f NH4+ + f NH3 deposition (Fig. 1 displays acidity, the negative of fAlk and fAlknitrif, for comparison with other fluxes). On a global basis, the alkalinity reduction from f SO42− + f SO2 and f NO3− is largely canceled by f NH4+ + f NH3 inputs, and the global ocean integrated anthropogenic fAlk input is only −0.24 Teq·y−1. Maximum deposition fluxes to the coastal ocean are −0.01 eq·m−2·y−1. Assuming complete nitrification of f NH4+ + f NH3 changes global ocean anthropogenic fAlknitrif input dramatically to −4.22 Teq·y−1, with maximum coastal fluxes of −0.01 to −0.10 eq·m−2·y−1.

Model ocean anthropogenic CO2 uptake is 138 Tmol·y−1, with spatial fDIC fluxes ranging from 0.1 to 2.0 mol C m−2·y−1. Highest anthropogenic fDIC values occur in regions of upwelling and water mass transformation (2, 24, 25). Globally, the ocean alkalinity reduction due to anthropogenic sulfur and nitrogen deposition, fAlknitrif, is at most, assuming full nitrification of ammonium deposition, approximately −3% of the fDIC inputs because of anthropogenic CO2 uptake. However, the alkalinity fluxes can be significant relative to anthropogenic fDIC fluxes in some coastal ocean and margin areas. Previous modeling studies (Terrestrial Ocean Atmosphere Ecosystem Model, TOTEM; refs. 26 and 27) estimate anthropogenic atmospheric nitrogen deposition to the global coastal ocean of 0.03 mol·m−2·y−1 for the turn of the 21st century, very similar to the estimates in Table 1. It was also shown that this flux will increase significantly during the next several decades, as will the reactive nitrogen flux to the coastal ocean from anthropogenic sources via rivers and groundwaters.

The anthropogenic alkalinity perturbation is redistributed by ocean circulation and initiates feedbacks by means of alterations in surface pH, air–sea CO2 flux, and [DIC]. Biogeochemical transformations must also be considered because of nitrogen buildup or eutrophication of surface waters, stimulating increased ocean primary production and organic matter export (27–30). We evaluate the responses by using a 3D marine physical/ecological/biogeochemical model (see Methods), focusing on three sensitivity experiments. Case 1 simulates direct alkalinity perturbations with no nutrient fertilization; fAlk alters surface [Alk]. Case 2 is similar to case 1, except assuming complete nitrification of fNH4+ + fNH3; fAlknitrif alters surface [Alk]. Case 3 incorporates explicit nitrogen cycle perturbations and allows for nutrient fertilization; fAlk alters surface [Alk], fNO3− alters surface [NO3−], and fNH4+ + fNH3 alters surface [NH4+]. All cases and a control (no atmospheric nitrogen and sulfur deposition) are integrated from 1990 to 2000, with repeat annual physics and increasing anthropogenic atmospheric CO2 based on observations.

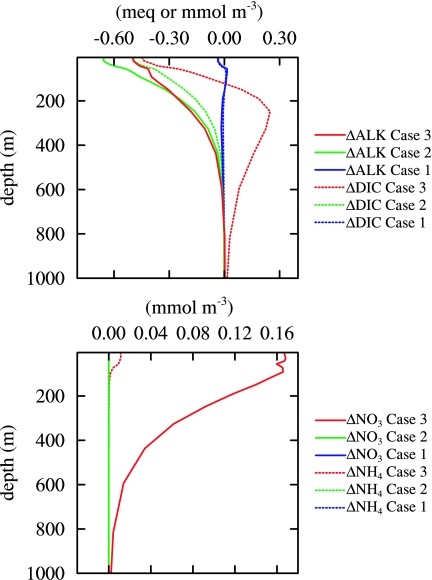

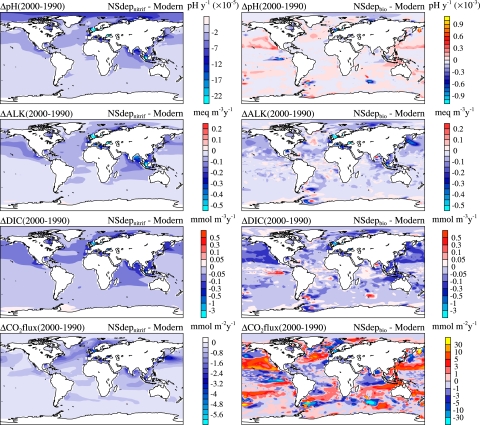

The direct effects of anthropogenic nitrogen and sulfur deposition in case 1 are small, in global integral, because alkalinity reductions from fNO3− and fSO4− + fSO2 are nearly balanced by increases from fNH4+ + fNH3 (Fig. 2). In case 2, with complete nitrification, we find a more clear reduction in surface water pH, [Alk], and [DIC] relative to the control simulation (Figs. 2 and 3). The lower surface water [DIC] arises because the negative [Alk] perturbations raise [pCO2] and drive a perturbation efflux of CO2 into the atmosphere, counter to the anthropogenic CO2 flux. The negative Δ[DIC] perturbations are comparable, although slightly smaller than Δ[Alk] in an absolute sense, so that pH still declines but with significantly smaller amplitude than would occur from the original Δ[Alk] perturbation alone. The largest surface water anomalies are found in coastal regions surrounding the emission areas, with trends ΔpH/Δt of −0.02 to −0.12 × 10−3 pH units·y−1, Δ[Alk]/Δt of −0.05 to −0.40 meq·m−3·y−1, and Δ[DIC]/Δt of −0.05 to −0.30 mmol·m−3·y−1. For comparison, the temporal trends in the anthropogenic CO2 control simulation are ΔpH/Δt of −0.8 to −1.8 × 10−3 pH units·y−1 and Δ[DIC]/Δt of +0.4 mmol·m−3·y−1 near the poles to +1.2 mmol·m−3·y−1 in the subtropics.

Fig. 2.

Perturbations to simulated global vertical profiles due to 10 years of anthropogenic atmospheric nitrogen and sulfur deposition. (Upper) Alkalinity (solid lines) and DIC (dashed lines). (Lower) NO3− (solid lines) and NH4+ (dashed lines). Case 1 is forced with alkalinity flux from Fig. 1, case 2 with the potential alkalinity flux (assuming complete nitrification), and case 3 with alkalinity and nitrogen fluxes allowing for biological feedbacks.

Fig. 3.

Perturbation maps of simulated surface water pH, DIC, and total alkalinity trends and air–sea CO2 flux due to anthropogenic atmospheric nitrogen and sulfur deposition.

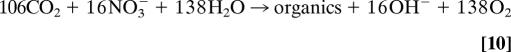

Biological feedbacks depend on three factors: (i) the extent to which nitrification transforms excess NH4+ into NO3−; (ii) vertical redistribution of the excess nitrogen by means of biological nitrogen uptake in the surface, particle sinking, and subsurface remineralization; and (iii) biological drawdown of surface [DIC] from eutrophication. The effect of primary production on alkalinity depends on the source of nitrogen (31, 32). NO3−-supported growth produces alkalinity (+1:1 eq/mol), and NH4+-supported growth removes alkalinity (−1:1 eq/mol):

|

|

Alkalinity sources/sinks from phosphorus uptake and release are an order of magnitude smaller. Note that the alkalinity changes resulting from biological nitrogen uptake are opposite in sign to those generated directly by the original atmospheric deposition flux (Eq. 7). Eventually, most of the extra organic nitrogen will be transported downward and remineralized in subsurface waters, releasing excess NH4+ that is almost immediately nitrified to NO3− in oxygenated waters.

The net effect of biological nitrogen cycling (case 3) is to reduce surface Δ[Alk] caused by atmospheric nitrogen deposition and to redistribute Δ[Alk] downward through the water column (Fig. 2). The impact, however, does not qualitatively alter the surface water alkalinity perturbations. The strongest negative surface Δ[Alk] anomalies in case 3 are somewhat smaller than those in case 2 but with greater spatial variability and some regions of positive trends (Fig. 3). Some of the spatial variability reflects the patterns of surface nutrient utilization, iron limitation, and the preferential biological uptake of NH4+ over NO3−. The increase in ocean nitrogen inventory in case 3 is smaller than the cumulative atmospheric nitrogen deposition of 2.7 Tmol·N·y−1 because elevated surface NO3− and productivity reduces simulated N2 fixation by 0.6 Tmol·N·y−1 and increases denitrification by 0.1 Tmol·N·y−1. Overall, nitrification modulates the acid/base signal from atmospheric nitrogen deposition, and fAlknitrif with net alkaline effects everywhere is a reasonable approximation for the vertically integrated alkalinity sink in most locations.

Increased primary production stimulated by atmospheric nitrogen deposition lowers surface DIC with a ratio of ≈6.6 C/N (mol/mol) (Eqs. 10 and 11). This results in qualitatively different solutions for pH and air–sea CO2 flux perturbations (case 3; Fig. 3). The negative Δ[DIC] anomalies are amplified substantially relative to case 2 in some regions, with Δ[DIC]/Δt trends of −0.3 to −0.5 mmol·m−3·y−1 over large areas. In many locations, Δ[DIC] decreases faster than Δ[Alk] and thus reverses the sign of the ΔpH signal, with ΔpH/Δt typically ranging from −0.2 to +0.2 × 10−3 pH units·y−1. The case 3 spatial fields are also considerably more patchy, reflecting small-scale readjustments in model primary production, subsurface nutrients, and DIC.

Implications and Future Research

On a global scale, the alterations in surface water chemistry from anthropogenic nitrogen and sulfur deposition are only a few percent of the ocean acidification and Δ[DIC] increases expected from the oceanic uptake of anthropogenic CO2. However, impacts on seawater chemistry can be much more substantial in coastal waters, on the order of 10–50% or more of the anthropogenic CO2-driven changes near the major source regions and in marginal seas. Although there are certainly caveats with the simulated coastal signals because the global ocean model does not fully resolve complex coastal physical and biological dynamics, the coastal amplification is clear. Ocean acidification is thought to be a significant threat to ecosystems, including coral reefs and coastal benthic and planktonic foodwebs dominated by calcifying organisms (10–13). Our study highlights the need to also consider the effects of non-CO2 acidification sources from atmospheric nitrogen and sulfur deposition, both through their direct effects on reducing ocean alkalinity and their indirect effects through nitrogen fertilization of marine phytoplankton.

Uncertainties regarding the magnitude of non-CO2 ocean acidification arise from errors in the anthropogenic sulfur and nitrogen deposition fluxes to the ocean, ocean circulation, and marine biogeochemical responses. Global deposition depends strongly on total emissions, with emission ranges of approximately ±16% for NOx (total plus lightning) (7, 33), ±27% for NHx (7, 34), and ±20% for SO2 (35). Spatial differences in emissions and atmospheric transport pathways will change the downwind deposition fluxes to the oceans. The overall spatial patterns are generally similar across most models but can vary locally because of small shifts in steep deposition gradients. For example, sulfate residence times for models range between 3 and 5 days (35), with our model at 3.4 days. This means that deposition to remote regions in other models could be larger, but that uncertainties should be within ≈50%, even in remote regions. The response of seawater carbonate thermodynamics to acidification is well constrained. Better estimates of the uncertainties due to ocean circulation and biology require exploration of the effect in other numerical models and against field observations.

Here we highlight the first-order impacts associated with anthropogenic atmospheric nitrogen and sulfur. More comprehensive studies on global change and coastal acid/base chemistry would need to include a range of additional processes. The extent of atmospheric neutralization of acidic compounds may be varying because of changes in mineral dust emissions and alkaline fly ash from coal-fired power plants. There is evidence, for example, of reduced atmospheric deposition of basic cations (e.g., Ca2+) (36). Although much of the acidity flux that falls on land will likely be neutralized by soils, some fraction may be transported to the ocean (10, 11, 29), and there are substantial riverine inputs of anthropogenic nitrogen and organic matter to the coastal domain (27, 30, 37). In the water column, second-order biological effects arise from altered rates of nitrogen fixation, water-column and sediment denitrification, calcification, and CaCO3 remineralization (14, 15, 38–40).

Methods

Preindustrial and current nitrogen deposition (including nitrate and ammonia) are simulated (33) in the MOZART model (41), based on climate simulations from the Parallel Climate Model (42) for 1890 and 1990, respectively. Emissions for both preindustrial and present-day come from the EDGAR–HYDE inventory (43). Present-day emissions of ammonia follow ref. 7, whereas preindustrial emissions are assumed to be zero. For the sulfate species, simulations are conducted within the Community Atmospheric Model (CAM3) (44), using sulfate chemistry based on ref. 45. Emissions for preindustrial and current climate for sulfur are based on ref. 46, and the preindustrial and current climates were simulated by using slab ocean model versions (47).

The ocean model combines a state-of-the-art marine ecosystem module (48) with phytoplankton functional groups (pico/nanoplankton, diatoms, diazotrophs, and calcifiers), multiple limiting nutrients (N, P, Si, and Fe), zooplankton, and several detrital pools. The model explicitly tracks both NO3− and NH4+ pools and includes nitrification, nitrogen fixation, and water-column denitrification (39, 49). The biogeochemistry module (50) has full carbonate system thermodynamics (21), and air–sea CO2 fluxes follow a quadratic wind-speed gas exchange relationship. The ecobiogeochemistry is embedded in the low-resolution (zonal 3.6°; meridional 0.8°–1.8°; 25 vertical layers with a 12-m-thick surface layer) National Center for Atmospheric Research ocean physical model (CCSM3.1), based on the Parallel Ocean Program (51). This model is integrated with a repeat annual cycle of surface forcing based on National Centers for Environmental Prediction reanalysis and satellite data products (52–54).

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Aeronautics and Space Administration Grant NNG05GG30G and National Science Foundation (NSF) Grant ATM06-28582 (to S.C.D. and I.L.), National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration Grant GC05-285 (to R.A.F.), and NSF Grants EAR02-23509 and ATM04-39051 (to F.T.M.). The National Center for Atmospheric Research is supported by the NSF.

Abbreviations

- Alk

total alkalinity

- DIC

dissolved inorganic carbon.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

References

- 1.Houghton JT, Ding Y, Griggs DJ, Noguer M, van der Linden PJ, Dai X, Maskell K, Johnson CA, editors. Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Climate Change 2001: The Scientific Basis. New York: Cambridge Univ Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mackenzie FT. In: Biotic Feedbacks in the Global Climatic System. Woodwell G, Mackenzie FT, editors. New York: Oxford Univ Press; 1995. pp. 22–46. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schlesinger WH. Biogeochemistry: An Analysis of Global Change. San Diego: Academic; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Irving PM, editor. National Acid Precipitation Assessment Program. Acidic Deposition: State of Science and Technology. Vol 1. Washington, DC: Govt Printing Office; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Howarth RW, Billen G, Swaney D, Townsend A, Jaworski N, Lajtha K, Downing JA, Elmgren R, Caraco N, Jordan T, et al. Biogeochemistry. 1996;35:75–139. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rodhe H, Dentener F, Schulz M. Environ Sci Technol. 2002;36:4382–4388. doi: 10.1021/es020057g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dentener F, Drevet J, Lamarque JF, Bey I, Eickhout B, Fiore AM, Hauglustaine D, Horowitz LW, Krol M, Kulshrestha UC, et al. Global Biogeochem Cycles. 2006;20:GB4003. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Likens GE, Bormann HF, Johnson NM. In: Some Perspectives of the Major Biogeochemical Cycles. Likens GE, editor. New York: Wiley; 1981. pp. 93–112. SCOPE Report No 17. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Driscoll CT, Lawrence GB, Bulger AJ, Butler TJ, Cronan CS, Eagar C, Lambert KF, Likens GE, Stoddard JL, Weathers KC. Biosciences. 2001;51:180–198. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Galloway JN. Water Air Soil Pollut. 2001;130:17–24. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Galloway JN. In: Interactions of the Major Biogeochemical Cycles. Melillo JM, Field CB, Moldan B, editors. Washington, DC: Island Press; 2003. pp. 259–272. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Orr JC, Fabry VJ, Aumont O, Bopp L, Doney SC, Feely RA, Gnanadesikan A, Gruber N, Ishida A, Joos F, et al. Nature. 2005;437:681–686. doi: 10.1038/nature04095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kleypas JA, Feely RA, Fabry VJ, Langdon C, Sabine CL, Robbins LL. Impacts of Ocean Acidification on Coral Reefs and Other Marine Calcifiers: A Guide for Future Research. Boulder, CO: Univ Corp Atmos Res; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Feely RA, Sabine CL, Lee K, Berelson W, Kleypas J, Fabry VJ, Millero FJ. Science. 2004;305:362–366. doi: 10.1126/science.1097329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Andersson AJ, Mackenzie FT, Lerman A. Global Biogeochem Cycles. 2006;20:GB1S92. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jickells TD. Science. 1998;281:217–222. doi: 10.1126/science.281.5374.217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zeebe RE, Wolf-Gladrow D. CO2 in Seawater: Equilibrium, Kinetics, Isotopes. Amsterdam: Elsevier; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sabine CL, Feely RA, Gruber N, Key RM, Lee K, Bullister JL, Wanninkhof R, Wong CS, Wallace DWR, Tilbrook B, et al. Science. 2004;305:367–371. doi: 10.1126/science.1097403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dickson AG. Deep-Sea Res. 1981;28:609–623. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Morel FMM. Principles of Aquatic Chemistry. New York: Wiley; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dickson AG, Goyet C, editors. Department of Energy. Handbook of Methods for the Analysis of the Various Parameters of the Carbon Dioxide System in Sea Water. Oak Ridge, TN: Oak Ridge National Laboratory, US Dept Energy; 1994. (ORNL/CDIAC-74) Available at http://cdiac.ornl.gov/oceans/handbook.html. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Morse JW, Mackenzie FT. Geochemistry of Sedimentary Carbonates. Amsterdam: Elsevier; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nakicenovic N, Alcamo J, Davis G, de Vries B, Fenhann J, Gaffin S, Gregory K, Grübler A, Jung TY, Kram T, et al. Emissions Scenarios: A Special Report of Working Group III of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. New York: Cambridge Univ Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Doney SC. Global Biogeochem Cycles. 1999;13:705–714. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mikaloff Fletcher SE, Gruber N, Jacobson AR, Doney SC, Dutkiewicz S, Gerber S, Follows M, Joos F, Lindsay K, Menemenlis D, et al. Global Biogeochem Cycles. 2006;20:GB2002. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ver LM, Mackenzie FT, Lerman A. Am J Sci. 1999;299:762–801. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mackenzie FT, Ver LM, Lerman A. Chem Geol. 2002;190:13–32. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Paerl HW. Can J Fish Aquat Sci. 1993;50:2254–2269. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mackenzie FT, Ver LM, Sabine C, Lane M, Lerman A. In: Interactions of C, N, P, and S Biogeochemical Cycles and Global Change. Wollast R, Mackenzie FT, Chou L, editors. Berlin: Springer; 1993. pp. 1–62. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Galloway JN, Dentener FJ, Capone DG, Boyer EW, Howarth RW, Seitzinger SP, Asner GP, Cleveland CC, Green PA, Holland EA, et al. Biogeochemistry. 2004;70:153–226. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Brewer PG, Goldman JC. Limnol Oceanogr. 1976;21:108–117. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Goldman JC, Brewer PG. Limnol Oceanogr. 1980;25:352–357. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lamarque J-F, Kiehl JT, Brasseur GP, Butler T, Cameron-Smith P, Collins WD, Collins WJ, Granier C, Hauglustaine D, Hess PG, et al. J Geophys Res. 2005;110:D19303. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bouwman AF, Lee DS, Asman WAH, Dentener FJ, Van Der Hoek KW, Olivier JGJ. Global Biogeochem Cycles. 1997;11:561–588. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Textor C, Schulz M, Guibert S, Kinne S, Balkanski Y, Bauer S, Berntsen T, Berglen T, Boucher O, Chin M, et al. Atmos Chem Phys. 2006;6:1777–1813. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hedin LO, Granat L, Likens GE, Adri Buishand T, Galloway JN, Butler TJ, Rodhe H. Nature. 1994;367:351–354. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Boyer EW, Howarth RW, Galloway JN, Dentener FJ, Green PA, Vorosmarty CJ. Global Biogeochem Cycles. 2006;20:GB1S91. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fennel K, Wilkin J, Levin J, Moisan J, O'Reilly J, Haidvogel D. Global Biogeochem Cycles. 2006;20:GB3007. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Moore JK, Doney SC. Global Biogeochem Cycles. 2007;21:GB2001. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Krishnamurthy A, Moore JK, Luo C, Zender CS. J Geophys Res. 2007;112:G02019. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Horowitz LW, Walters S, Mauzerall DL, Emmons LK, Rasch PJ, Granier C, Tie X, Lamarque J-F, Schultz MG, Tyndall GS, et al. J Geophys Res. 2003;108:4784. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Washington WM, Weatherly JW, Meehl GA, Semtner AJ, Jr, Bettge TW, Craig AP, Strand WG, Jr, Arblaster J, Wayland VB, James R, Zhang Y. Clim Dyn. 2000;16:755–774. [Google Scholar]

- 43.van Aardenne JA, Dentener FJ, Olivier JGJ, Klein CGM. Global Biogeochem Cycles. 2001;15:909–928. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Collins WD, Blackmon M, Bitz CM, Bonan GB, Bretherton CS, Carton JA, Chang P, Doney S, Hack JJ, Kiehl JT, et al. J Clim. 2006;19:2122–2143. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rasch PJ, Collins W, Eaton BE. J Geophys Res. 2001;106:7337–7355. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Smith SJ, Conception E, Andres R, Lurz J. Historical Sulfur Dioxide Emissions 1850–2000: Methods and Results. Richland, WA: Pacific Northwest Natl Lab; 2004. PNNL-14537. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kiehl J, Shields C, Hack J, Collins W. J Clim. 2006;19:2584–2596. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Moore JK, Doney SC, Lindsay K. Global Biogeochem Cycles. 2004;18:GB4028. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Moore JK, Doney SC, Lindsay K, Mahowald N, Michaels AF. Tellus B Chem Phys Meteorol. 2006;58:560–572. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Doney SC, Lindsay K, Fung I, John J. J Clim. 2006;19:3033–3054. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Smith R, Gent P. Reference Manual for the Parallel Ocean Program (POP) Los Alamos, NM: Los Alamos Natl Lab; 2004. LAUR-02-2484. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Doney SC, Large WG, Bryan FO. J Clim. 1998;11:1420–1441. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Large WG, Yeager SG. Diurnal to Decadal Global Forcing for Ocean and Sea-Ice Models: The Data Sets and Flux Climatologies. Boulder, CO: Natl Center Atmos Res; 2004. Technical Note NCAR/TN-460+STR. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Doney SC, Yeager S, Danabasoglu G, Large WG, McWilliams JC. J Phys Oceanogr. 37:1918–1938. [Google Scholar]