Abstract

Endo180, a member of the mannose receptor family, is constitutively recycled between clathrin-coated pits on the cell surface and intracellular endosomes. Its large extracellular domain contains an N-terminal cysteine-rich domain, a single fibronectin type II domain and eight C-type lectin-like domains. The second of these lectin-like domains has been shown to mediate Ca2+-dependent mannose binding. In addition, cross-linking studies have identified Endo180 as a urokinase plasminogen activator receptor–associated protein and this interaction can be blocked by collagen V. Here we demonstrate directly using in vitro assays, cell-based studies and tissue immunohistochemistry that Endo180 binds both to native and denatured collagens and provide evidence that this is mediated by the fibronectin type II domain. In cell culture systems, expression of Endo180 results in the rapid uptake of soluble collagens for delivery to lysosomal degradative compartments. Together with the observed restricted expression of Endo180 in both embryonic and adult tissue, we propose that Endo180 plays a physiological role in mediating collagen matrix remodelling during tissue development and homeostasis and that the observed receptor upregulation in pathological conditions may contribute to disease progression.

INTRODUCTION

Collagens represent the most abundant group of proteins in vertebrates where they play important roles in the development, morphogenesis, and growth of many tissues (Eyre, 1980; Mayne and Brewton, 1993). In addition to their mechanical properties, collagens also act as substrates for cell attachment and migration and mediate signaling events by binding to cells surface receptors such as integrins, discoidin domain receptors (DDRs), and glycoprotein VI (Vogel et al., 2001).

To maintain correct tissue homeostasis, the synthesis, deposition, and degradation of collagens, which is mainly carried out by fibroblasts, must be coordinately regulated. Imbalances in collagen metabolism are manifested in pathological conditions such as inflammation, fibrosis, and tumor metastasis (Perez-Tamayo, 1978; Prockop and Kivirikko, 1995). To date, several different mechanisms have been proposed for the remodeling of existing collagen networks. Many studies have demonstrated a major function for matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) in collagen dissolution (Lauer-Fields et al., 2002). However, although MMPs have been linked to the extracellular breakdown of collagens during inflammation (Leppert et al., 2001) and cancer progression (Johansson et al., 2000), an alternative intracellular degradation pathway takes place at other sites of rapid collagen turnover such as periodontium (Svoboda et al., 1981) and healing wounds (McGaw and Ten Cate, 1983). This intracellular catabolytic pathway occurs predominantly via phagocytosis of collagen fibrils mediated by integrins, primarily by integrin α2β1 with a potential regulatory contribution by integrin α3β1. The ingested collagen is subsequently transported to lysosomes and degraded by proteases of the cathepsin family (Everts et al., 1985; Arora et al., 2000).

A separate tissue specific system for the uptake of denatured collagen has been described in liver endothelial cells where a collagen scavenger receptor, which only recognizes monomeric collagen α-chains but not their native triple helical form, mediates the elimination of circulating collagen waste products from the blood stream (Smedsrod et al., 1985, 1990). In contrast to the integrin-mediated phagocytic route, the collagen scavenger receptor internalizes collagen via an endocytic route with subsequent delivery of the collagenous cargo from the endosomes to lysosomal compartments (Hellevik et al., 1996). This demonstration of multiple pathways for collagen uptake raises two important questions: first, do different pathways exist for the internalization of different collagens, and second, although uptake pathways have been described in specialized tissues, are the same pathways utilized in nonspecialized tissues and in particular in stromal fibroblasts?

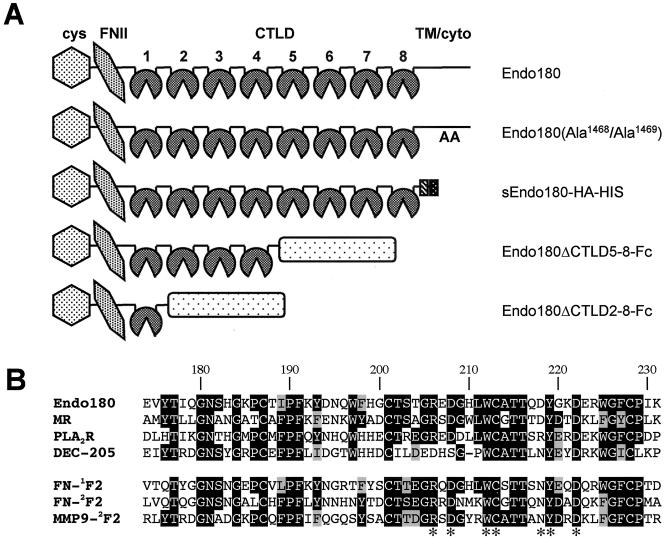

To address these questions, we have investigated the recently described receptor Endo180. Endo180 is the fourth and final member of the mannose receptor family, which also comprises the mannose receptor, the M-type phospholipase A2 (PLA2R) receptor and DEC-205 (East and Isacke, 2002). All 4 receptors contain an N-terminal cysteine-rich or ricin-type domain, a fibronectin type II (FNII) domain, 8 C-type-lectin domains (CTLDs; 10 in the case of DEC-205), a single transmembrane domain, and a short cytoplasmic domain (see Figure 1A). The proposal that Endo180 might function as a collagen receptor comes from two sources. First, FNII domains in other proteins including fibronectin and the gelatinases MMP2 and MMP9 (see Figure 1B) have been demonstrated to confer binding to denatured collagen (gelatin; Steffensen et al., 1995; Pickford et al., 2001). Second, Endo180 has been identified as part of a trimolecular cell surface complex together with prourokinase plasminogen activator (prouPA) and the uPA receptor (uPAR), hence its alternative name of uPAR associated protein, uPARAP. Formation of this complex is inhibited by collagen V and to a lesser extent by collagen I and collagen IV (Behrendt et al., 2000). Here we have directly determined the capacity of Endo180 to act as a collagen receptor using a combination of in vitro and cell-based assays.

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of Endo180 constructs and sequence comparison of fibronectin-type II (FNII) domains. (A) Structure of Endo180 showing the FNII domain located between the cysteine-rich domain (cys) and eight C-type lectin-like domains (CTLD). In the Endo180(Ala1468/Ala1469) construct the leucine-valine endocytosis motif in the cytoplasmic domain (cyto) has been mutated to two alanine residues (Howard and Isacke, 2002). Soluble constructs were generated in which the Endo180 extracellular domain was fused in frame with a hemagglutinin and histidine tag (sEndo180-HA-HIS) or in which Endo180 truncated after CTLD4 (Endo180ΔCTLD5–8-Fc) or after CTLD1 (Endo180ΔCTLD2–8-Fc) was fused in frame with the Fc tail of human IgG1. (B) The FNII domain of human Endo180 is aligned with the FNII domains of the other members of the mannose receptor family (MR, mannose receptor; PLA2R, phospholipase A receptor), FN-12F2 and FN-2F2, first and second FNII domains of fibronectin; MMP9-2F2, second FNII domain of matrix metalloproteinase 9. Numbering refers to the amino acid sequence of human Endo180. Identical residues and residues with conservative changes are shown in black and gray, respectively. Residues found to be important for gelatin binding in MMP9 are marked with an asterisk.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Reagents

Protein G-Sepharose and gelatin-Sepharose were purchased from Amersham Pharmacia Biotech (Piscataway, NJ). Collagen I, IV, and V, fibronectin, laminin, and vitronectin were obtained from BD Biosciences (Bedford, MA). Collagen II was from Calbiochem (San Diego, CA). TO-PRO-3, FITC-BSA, OregonGreen488-gelatin (OG-gelatin) and OregonGreen488-collagen IV (OG-collagen IV) were purchased from Molecular Probes (Eugene, OR). Collagen V was labeled using the FITC labeling kit from Calbiochem according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Antibodies and Cells

The generation of anti-human Endo180 monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) A5/158 and E1/183 and a cross-species–reactive anti-Endo180 polyclonal antiserum has been described elsewhere (Isacke et al., 1990; Sheikh et al., 2000). Anti-human LAMP1 mAb H4A3 was obtained from Prof. C. Hopkins (Imperial College, London). Antibodies against human integrins α2, α3, αV, and β1 were kindly provided by Dr. Fiona Watt (Cancer Research UK). The following collagen antibodies were purchased from DPC Biermann (Bad Nauheim, Germany): rabbit anticollagen I (R1038), anti-collagen IV (R1041), and anti-collagen V (R1042). Horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated anti-mouse Ig was purchased from Jackson Immunoresearch (West Grove, PA). FITC anti-human Fc was purchased from Sigma (St. Louis, MO). Alexa488- and Alexa555-conjugated secondary antibodies were obtained from Molecular Probes. Cells were cultured in DME, 10% fetal calf serum, which was supplemented with 10 μg/ml insulin for the MCF-7 cells. To generate permanently expressing lines, MCF-7 and T47D cells were transfected with the pcDNA3-Endo180 (Sheikh et al., 2000), pcDNA3ΔHindIII-Endo180(Ala1468/Ala1469; Howard and Isacke, 2002), or with empty pcDNA3 vector using Lipofectamine and selection with G418 (0.5 mg/ml). Cell populations were enriched for Endo180-expressing cells by fluorescence activated cell sorting (FACS) using the anti-Endo180 mAb A5/158. For downregulation of endogenous Endo180 the following small interfering (siRNA) oligonucleotides were used: Endo180 siRNA oligonucleotides 5′CCCAACGUCUUCCUCAUCU dT dT3′ and 3′AGAUGAGGAAGACGUUGGG dT dT5′; reversed Endo180 (control) siRNA oligonucleotides 5′UCUACUCCUUCUGCAACCC dT dT3′ and 5′GGGUUGCAGAAGGAGUAGA dT dT3′. Annealed siRNA oligonucleotides (0.5 nmol/ml) were transfected into MG-63 cells seeded onto glass coverslips or culture dishes (30–50% confluent) with 100 μM Oligofectamine (Invitrogen, Paisley, United Kingdom) in Opti-MEM reduced serum medium (Invitrogen). Cells were incubated at 37°C for 4 h before the addition of FCS to 10% and cultured for a further 68 h.

Generation, Expression, and Purification of Endo180 Constructs

The generation of the pIgplus-Endo180ΔCTLD5–8-Fc (East et al., 2002) has been described previously. To generate the Endo180ΔCTLD2–8-Fc construct, PCR reactions were performed with Expand long polymerase (Roche Molecular Biochemicals, Lewes, United Kingdom) and pcDNA3-Endo180 as a template with a 5′ modified T7 primer (5′CTGGCTTATCGAAATTAATACGACTCACTATAGGGA3′) and the 3′ primer (5′GTCTCGAGGTCTGGAGGGGTGGGCTCGGCC3′) located between CTLD1 and CTLD2, where bases underlined indicate an XhoI restriction site. Amplified DNA was digested with HindIII and XhoI and ligated into the pIgplus vector (R&D Systems, Abingdon, United Kingdom) digested with the same enzymes. In the pcDNA3ΔHindIII-sEndo180-HA-HIS plasmid the Endo180 extracellular domain was truncated at the end of CTLD8 (amino acid 1395) and fused in frame with a hemagglutinin (HA) tag, a 6× histidine (HIS) tag, and a stop codon (Rivera-Calzada et al., 2003). pIgplus-Endo180-Fc constructs and the pcDNA3ΔHindIII-sEndo180-HA-HIS construct were expressed in COS-1 cells as previously described (East et al., 2002). The supernatants were harvested after a 7-d period and loaded on a 1-ml Protein G-Sepharose column (Fc constructs) or onto a 1-ml column in which the anti-Endo180 mAb E1/183 had been coupled to cyanogen bromide–activated Sepharose (sEndo180-HA-HIS). The columns were washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), and the fusion proteins were eluted with 0.1 M glycine, pH 2.5. Fractions (1 ml) were collected and neutralized with 1 M Tris-HCl, pH 9.0. Fractions containing the fusion proteins were pooled and dialyzed against PBS.

Gelatin-Sepharose Binding Assay

A gelatin-Sepharose or Sepharose column (2 ml) was equilibrated with loading buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 5 mM CaCl2) and loaded with 1 ml of Endo180ΔCTLD5–8-Fc (20 μg/ml in loading buffer). The flow-through was collected, and the columns were washed with 5 × 2 ml of loading buffer followed by 6 × 1 ml of elution buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 500 mM NaCl). Fractions were precipitated by incubation with 40 μg of bovine serum albumin (BSA) and 0.5 ml of 30% trichloroacetic acid for 30 min on ice and then centrifuged for 10 min at 4°C at 15,000 × g. The pellets were washed twice in 1:1 ethanol ether, air-dried for 10 min, and resuspended in 40 μl of nonreducing sample buffer. Samples (10 μl) were resolved by 10% SDS PAGE and transferred to nitrocellulose, and Endo180 was detected using mAb A5/158 followed by HRP-conjugated anti-mouse Ig. Blots were developed using ECL reagent (Amersham Pharmacia).

Microwell Matrix Protein Binding Assay

Ninety-six–microwell plates (E.I.A./R.I.A, high binding, Costar, High Wycombe, United Kingdom) were incubated overnight at 4°C followed by 1 h at 37°C with 100 μl of the following extracellular matrix components. Collagen type I, type II, type IV, type V, and gelatin (all at 10 μg/ml in 10 mM acetic acid), fibronectin, laminin, vitronectin, and BSA (all at 10 μg/ml in PBS). Plates were rinsed three times with 0.3% BSA in PBS, blocked in the same solution for 1 h at 20°C, and then incubated with 100 μl of Endo180 constructs (4 μg/ml in PBS) for 1 h at 20°C. For competition experiments, stock solutions of collagen I, collagen IV, and gelatin (1 mg/ml in 10 mM acetic acid) were neutralized with 0.2 vol of 1 M Tris, pH 7.6, and preincubated in a 1:1 ratio with Endo180 constructs (8 μg/ml in PBS). Bound Endo180 constructs were detected with 10 μg/ml mAb E1/183 followed by 1 μg/ml HRP anti-mouse IgG using o-phenylenediamine dihydrochloride (Sigma) as a substrate. The reaction was stopped by adding 3 M HCl, and the absorption was quantified in an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) plate reader (Spectramax 384 plus, Molecular Devices, Wokingham, United Kingdom) at a wavelength of 492 nm. As negative controls human IgG and secondary antibody alone were used.

Flow Cytometry

Cells were harvested by exposure to trypsin/EDTA (Sigma) for 1 min at 37°C, washed in DME containing 10% FCS and stained on ice with 10 μg/ml anti-Endo180 mAb A5/158 or anti-integrin mAbs for 20 min followed by 2 μg/ml Alexa488 anti-mouse Ig for 20 min, washed twice, fixed with 1% paraformaldehyde, and analyzed on a Becton Dickinson (Oxford, United Kingdom) FACScan flow cytometer. For the collagen-binding studies, cells were seeded on 6-well tissue culture dishes and grown to 70–90% confluency. Cells were starved for 1 h with serum-free DME and then incubated with OG-gelatin, OG-collagen IV, FITC-collagen V, or FITC-BSA at 20 μg/ml in serum-free DME for 2 h. Cells were then washed with PBS, harvested, fixed, and FACS-analyzed as above.

Immunostaining

Cells seeded on glass coverslips were stained for cell surface Endo180 by incubation with 10 μg/ml mAb A5/158 at 4°C for 60 min. Cells were then fixed for 20 min with 3% paraformaldehyde, permeabilized with 0.2% saponin, and incubated for 45 min with 2 μg/ml Alexa555 anti-mouse Ig. For intracellular staining, cells were fixed with 3% paraformaldehyde and permeabilized with 0.2% saponin before incubation with primary and secondary antibodies. Nuclei were counterstained with TO-PRO-3 (Molecular Probes) and images were collected sequentially in three channels on a Leica TCS SP2 confocal microscope (Milton Keynes, United Kingdom). For immunohistochemistry of murine kidney, 25-μm Vibratome sections were cut from 4% paraformaldehyde fixed (1 h) adult female C3H murine kidneys. Sections were then permeabilized with 0.5% Triton X-100 for 30 min, blocked for 30 min with immunofluorescence buffer (PBS containing 1% BSA and 2% FCS), and incubated for 3 h at 37°C in 100 μl of Endo180ΔCTLD5–8-Fc (100 μg/ml in immunofluorescence buffer) followed by FITC anti-human Fc for 1 h at room temperature. Nuclei were counterstained with TO-PRO-3 and sections were dried onto poly-d-lysine–coated glass slides. Where indicated, sections were double-labeled with anti-collagen antibodies followed by Alexa555 anti-rabbit Ig. For controls, sections were pretreated for 5 min at 37°C with DME containing 0.2% type I collagenase (Sigma C-0130) or probed with Endo180ΔCTLD5–8-Fc that had been preincubated with 2 μg/ml collagen I (37°C, 1 h). For immunohistochemistry of human breast, 7-μm cyrosections were cut from normal adult human breast and stored at –80°C. Sections were thawed, fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 40 min, and then stained with anti-Endo180 mAb A5/158 and anti-collagen I antibody followed by Alexa555 anti-mouse Ig and Alexa4888 anti-rabbit Ig and counterstained with TO-PRO-3.

RESULTS

Endo180 Binds to Collagens

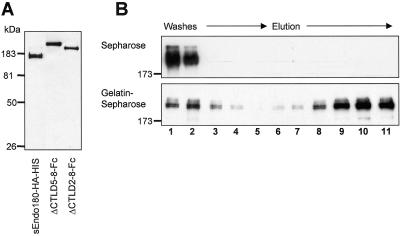

The FNII domain is the most highly conserved (44–63% sequence identity) domain within members of the mannose receptor family and shares 45 and 42% sequence identity with the gelatin/collagen-binding FN-1F2 and FN-2F2 domains of fibronectin, respectively (Figure 1B). Sequence analysis of this domain in Endo180 shows that it has conserved all but one of the amino acid residues found to be essential for the gelatin-binding activity of MMP9 (Collier et al., 1992), making gelatin/collagen an obvious candidate for an Endo180 ligand. To investigate a possible interaction between Endo180 and collagen, we generated a series of soluble Endo180 extracellular domain constructs fused either to an HA-HIS tag or to the Fc portion of human IgG1 (Figure 1A) and expressed these fusion proteins in COS-1 cells (Figure 2A). In initial studies, a fusion protein deleted after CTLD4 (Endo180ΔCTLD5–8-Fc) was tested for its ability to bind to gelatin (denatured collagen I) immobilized on Sepharose. The results show for the first time a direct interaction between Endo180 and denatured collagens.

Figure 2.

Soluble Endo180 binds denatured collagen. (A) Purified sEndo180-HA-HIS, Endo180ΔCTLD5–8-Fc, and Endo180ΔCTLD2–8-Fc were resolved by 8% nonreducing SDS PAGE and blotted onto nitrocellulose. The blot was probed with the anti-Endo180 mAb E1/183 followed by HRP anti-mouse Ig and ECL detection. Note the size of the Fc constructs reflects their Fc-mediated dimerization. (B) Endo180ΔCTLD5–8-Fc (20 μg) was loaded onto Sepharose or gelatin-Sepharose columns, and wash (1–5) and elution (6–11) fractions were analyzed by Western blotting as described in MATERIALS AND METHODS.

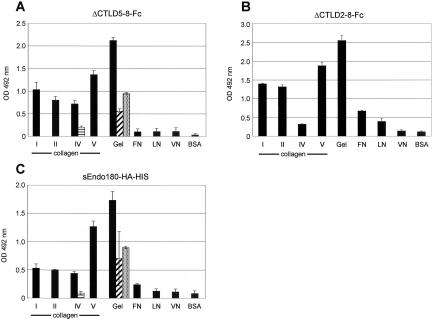

To determine the binding specificity of this construct, ELISA assays were performed with gelatin, collagens, and other extracellular matrix components as substrates. Endo180ΔCTLD5–8-Fc bound to gelatin and the four different collagen types tested (type I, type II, type IV, and type V), whereas only background binding was detected on fibronectin, laminin, or vitronectin. The binding to gelatin could be substantially competed by collagen I or collagen IV. Conversely, collagen IV binding was reduced to background levels by preincubation of the Endo180ΔCTLD5–8-Fc with gelatin, demonstrating that binding of collagens and gelatin can be cross competed and does not require CTLDs 5–8. However, this fusion protein retains CTLD2 which has previously been demonstrated to mediate the Ca2+-dependent Endo180 sugar binding (East et al., 2002).

To further define the collagen-binding domain in Endo180, parallel assays were performed with Endo180ΔCTLD2–8-Fc in which CTLD2 had been deleted (Figure 1A). Endo180ΔCTLD2–8-Fc showed a similar binding profile to Endo180ΔCTLD5–8-Fc, with the exception that binding to collagen IV was reduced (Figure 3B). In addition, Endo180ΔCTLD5–8-Fc collagen binding was retained in the presence of the calcium chelator EDTA (our unpublished results), indicating that collagen binding is distinct from Endo180 C-type lectin activity. Finally, these binding data are not an artifact arising from the use of truncated Endo180 constructs or due to the presence of an Fc tail, which results in dimerization of the fusion proteins (Figure 2A) as an independent monomeric construct containing the entire Endo180 extracellular domain, sEndo180-HA-HIS (Figure 1A), bound to gelatin and collagens but not other extracellular matrix components, and again the gelatin and collagen binding could be cross-competed (Figure 3C). These data provide further evidence that in common with equivalent domains from fibronectin, MMP2, and MMP9, it is the Endo180 FNII domain that mediates the observed collagen binding. However, because an Fc-construct containing only the cysteine-rich and FNII domains is unstable, the possibility that the FNII neighboring domains contribute to collagen binding cannot be excluded.

Figure 3.

Binding specificity of soluble Endo180. Collagens I, II, IV, V, gelatin, fibronectin (FN), laminin (LN), vitronectin (VN), or BSA were immobilized onto multititer plates, incubated with Endo180ΔCTLD5–8-Fc (A), Endo180ΔCTLD2–8 (B), or sEndo180-HA-HIS followed by Endo180 mAb E1/183 and HRP anti-mouse Ig. The amount of bound construct was quantified using the OPD substrate on an absorbance plate reader set at 492 nm. The effects of preincubation of the constructs with collagens is as follows: gelatin competition for collagen IV binding (horizontal striped bars), collagen I competition for gelatin binding (hatched bars), collagen IV competition for gelatin binding (stippled bars). Values are the mean results from triplicate samples ± SD. Equivalent results were obtained in at least three separate experiments.

Endo180 Functions in Cells as a Collagen Binding and Internalization Receptor

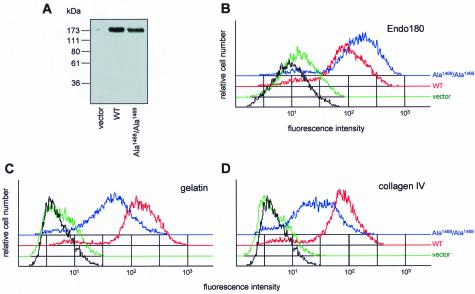

To study the binding of collagen to cellular Endo180, we screened several lines for their Endo180 expression and found the breast cancer cell line MCF-7 to be Endo180 negative. MCF-7 cells were transfected with a wild-type Endo180 construct, with an Endo180 mutant in which the dihydrophobic Leu1468/Val1469 endocytosis motif in the cytoplasmic domain had been mutated to alanines, Endo180(Ala1468/Ala1469) (Howard and Isacke, 2002), and with vector alone. Characterization of these transfected populations by Western blotting confirmed that wild-type Endo180 and Endo180(Ala1468/Ala1469) were expressed at the correct molecular weight of 180 kDa (Figure 4A). Immunofluorescence microscopy revealed that their distribution was as previously reported in transfected fibroblasts (Howard and Isacke, 2002; see Figures 5 and 8A) in that wild-type Endo180 was localized in a punctate distribution on the cell surface and in intracellular endosomes, whereas the nonendocytic Endo180(Ala1468/Ala1469) mutant was exclusively found on the cell surface. FACS was used to obtain cell populations in which at least 80% of the cells stably expressed the appropriate construct (Figure 4B).

Figure 4.

Collagen binding by MCF-7 cells transfected with Endo180. (A) MCF-7 cells transfected with wild-type (WT) Endo180, Endo180(Ala1468/Ala1469), or with pCDNA3 vector alone were subject to Western blot analysis using anti-Endo180 mAb E1/183 followed by HRP anti-mouse Ig. (B) In parallel, cells were stained with mAb E1/183 followed by Alexa488 anti-mouse Ig and analyzed by FACS. Black lines show binding of second antibody alone to WT Endo180–transfected cells. Eighty-two percent and 88% of the cells expressed WT Endo180 and Endo180(Ala1468/Ala1469), respectively. To assess collagen binding, MCF-7 cells expressing wild-type Endo180 (red), Endo180(Ala1468/Ala1469) (blue), or vector alone (green) seeded for 2 d were incubated with OregonGreen488 (OG)-gelatin (C) or OG-collagen IV (D) in serum-free DME for 2 h at 37°C. Cells were then washed, detached, and subject to FACS analysis. Black lines indicate binding of FITC-BSA to wild-type Endo180-expressing cells.

Figure 5.

Endo180 mediates uptake of collagen. MCF-7 cells transfected with vector alone, WT Endo180, or Endo180(Ala1468/Ala1469) and incubated with OG-gelatin (green) as described in Figure 4 were fixed, permeabilized, and stained with anti-Endo180 mAb A5/158 followed by Alexa555 anti-mouse Ig (red), and nuclei were counterstained with TO-PRO-3 (blue). Confocal xy horizontal sections are shown in main panels, and xz and yz vertical sections are shown to the right and below, respectively. Bar, 20 μm.

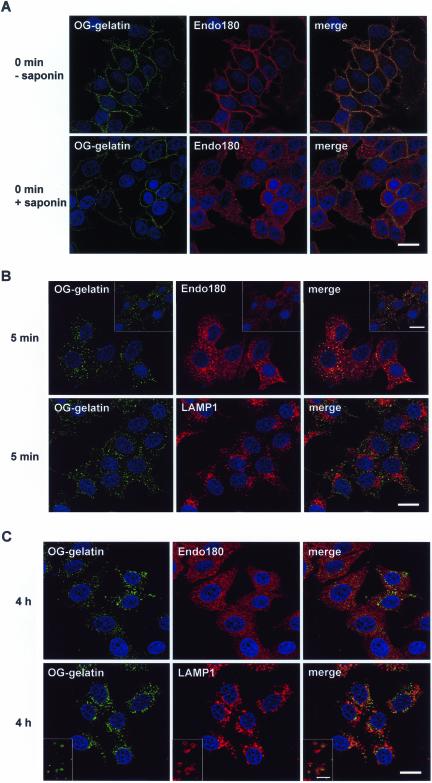

Figure 8.

Distribution of gelatin in Endo180-expressing MCF-7 cells. MCF-7 cells expressing wild-type Endo180 were incubated with OG-gelatin or OG-collagen IV (green) at 4°C and then warmed to 37°C as described in MATERIALS AND METHODS. At times indicated cells were stained with anti-Endo180 mAb A5/158 or anti-LAMP1 mAb H4A3 followed by Alexa555 anti-mouse Ig (red), and the nuclei were counterstained with TO-PRO-3 (blue) and analyzed by confocal microscopy. (A) Cells were either incubated with anti-Endo180 mAb together with OG-gelatin at 4°C for 1 h and then fixed, permeabilized, and incubated with Alexa555 anti-mouse Ig (top panels) or incubated with OG-gelatin at 4°C for 1 h, fixed, permeabilized and then stained for Endo180 (bottom panels). (B) Cells warmed to 37°C for 5 min were fixed, permeabilized, and stained for Endo180 (top panels) or LAMP1 (bottom panels). Insets in top panels show parallel cultures incubated with OG-collagen IV and stained for Endo180. (C) Cells warmed to 37°C for 4 h were fixed, permeabilized, and stained for Endo180 (top panels) or LAMP1 (bottom panels). Insets in bottom panels show higher magnification images of main panel. Bar, 20 μm except inset in C where bar, 4 μm.

To determine their collagen-binding ability, transfected MCF-7 cells were incubated for 2 h at 37°C with OregonGreen488(OG)-gelatin, OG-collagen IV, FITC-collagen V, or FITC-BSA. Analysis of the cells by flow cytometry revealed that significantly more gelatin was associated with the wild-type Endo180-expressing MCF-7 cells than with vector alone–transfected cells (Figure 4C). This was not due to a nonspecific increase in pinocytotic or endocytotic activity because both Endo180 and vector alone–transfected cells show an equivalent background level of FITC-BSA binding (Figure 4, C and D, and our unpublished results). A similar binding profile was observed with OG-collagen IV (Figure 4D) and FITC-collagen V (our unpublished results). Moreover, unlabeled gelatin was shown to effectively block OG-collagen IV binding, whereas both collagen I and collagen IV could compete for OG-gelatin binding (our unpublished results). Interestingly, MCF-7 cells expressing Endo180(Ala1468/Ala1469) showed higher levels of cell surface receptor but lower levels of associated gelatin and collagen than wild-type Endo180-expressing cells. To determine whether this difference in binding reflected the ability of wild-type Endo180, but not Endo180(Ala1468/Ala1469), to internalize and thereby accumulate collagens, cells incubated with OG-gelatin were stained for Endo180 and examined by confocal microscopy (Figure 5). No Endo180 expression or OG-gelatin binding was detected in vector alone–transfected cells. In sharp contrast, wild-type Endo180-expressing cells showed strong gelatin staining distributed in a vesicular pattern throughout the cells. Cross-sectional analysis of confocal stacks clearly revealed the gelatin localized intracellularly. MCF-7 cells expressing the nonendocytic Endo180(Ala1468/Ala1469) mutant also showed strong binding of gelatin. However, in both horizontal and vertical sections, this gelatin was exclusively colocalized with Endo180(Ala1468/Ala1469) at the cell surface.

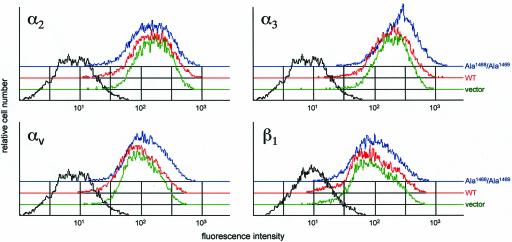

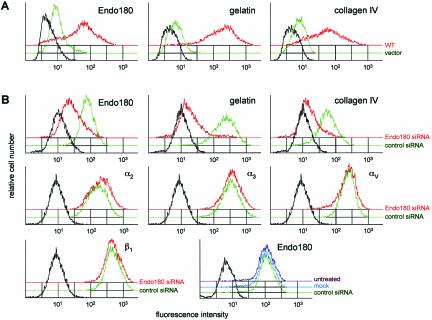

To confirm that these results were due to a specific interaction between collagens and cellular Endo180, the following control experiments were undertaken. First, the possibility that collagen binding in Endo180-expressing cells resulted from an upregulation of other collagen receptors was addressed. In the majority of cell types, the principal collagen receptor is integrin α2β1 (Lee et al., 1996) although integrins α1, α3, and αV also have collagen-binding activity (Davis, 1992). By flow cytometry analysis, cell surface expression of integrins α2, α3, αV, and β1 was not changed after transfection with either wild-type Endo180 or Endo180(Ala1468/Ala1469; Figure 6). Although it cannot be ruled out that Endo180 expression results in up-regulation of a nonintegrin collagen receptor such as DDR1 (Vogel et al., 2000), these data demonstrate that Endo180 does not have a nonspecific effect on cell surface expression of other transmembrane receptors. Second, collagen-binding experiments were repeated in an independent cell line. The T47D mammary carcinoma cells have low levels of endogenous Endo180 expression and bind correspondingly low levels of gelatin and collagen IV (Figure 7A). T47D cells were transfected with Endo180 and expression confirmed by flow cytometry (Figure 7A), Western blotting, and immunofluorescence microscopy (our unpublished results). In a manner similar to that described for MCF-7 cells, transfection of exogenous Endo180 in T47D cells strongly enhanced the association with gelatin and collagen IV. Third, it was important to establish that endogenous Endo180 could mediate collagen binding and that the results obtained with the MCF-7 cells and T47D cells were not an artifact of the transfection system. As previously described (Howard and Isacke, 2002), the osteosarcoma cell line MG-63 is Endo180 positive (Figure 7B), and although levels of expression are lower than observed in the transfected populations, these cells showed strong gelatin and collagen binding. Using siRNA, the expression of Endo180 in MG-63 cells could be markedly reduced compared with cells treated with control siRNA oligonucleotides. This effect was specific for Endo180 in that the control siRNA oligonucleotides had no effect on Endo180 expression, whereas the Endo180 siRNA oligonucleotides had no effect on expression of integrins α2, α3, αV, and β1. In agreement with the data obtained with transfected MCF-7 cells (Figure 4), downregulation of Endo180 almost completely abolished the ability of the MG-63 cells to bind gelatin and collagen (Figure 7B). Identical results were obtained by siRNA treatment of the Endo180-expressing HT1080 fibrosarcoma cells (our unpublished results). Together these data confirm that Endo180, both exogenous and endogenous, can act as a collagen-binding receptor and that the endocytic activity of Endo180 is required for collagen internalization.

Figure 6.

Expression of Endo180 in MCF-7 cells does not alter cell surface integrin levels. MCF-7 cells expressing wild-type Endo180 (red), Endo180(Ala1468/Ala1469) (blue), or vector alone (green) were incubated with mAbs directed against α2, α3, αV integrins followed by Alexa488 anti-mouse Ig or with a FITC-conjugated anti-β1 integrin mAb and were FACS-analyzed. Profiles in black represent wild-type Endo180-expressing cells incubated with second antibody alone(α2, α3, αV) or no antibody (β1).

Figure 7.

Expression of Endo180 in T47D breast carcinoma cells results in collagen binding, whereas downregulation of endogenous Endo180 in MG-63 cells reduces collagen binding. (A) T47D cells were transfected with vector alone (green) or wild-type Endo180 (red), subjected to one round of cell sorting, and analyzed by FACS using anti-Endo180 mAb E1/183 followed by Alexa488 anti-mouse Ig. Seventy-seven percent of the latter cells expressed Endo180. Black line indicates binding of second antibody alone to Endo180-expressing cells. To assess collagen binding, T47D cells seeded for 2 d were incubated with OG-gelatin or OG-collagen IV in serum-free DME for 2 h at 37°C. Cells were then washed, detached, and subjected to FACS analysis. Black lines indicate binding of FITC-BSA to Endo180-expressing cells. (B) MG-63 cells treated for 72 h with Endo180 siRNA oligonucleotides or control siRNA oligonucleotides were assayed for Endo180 expression and gelatin or collagen IV binding as described for T47D cells. FACS analysis of integrin expression was as in Figure 6. To confirm that control siRNA treatment did not alter Endo180 expression, parallel dishes of cells were mock-transfected with Oligofectamine or left untreated. Black lines indicate binding of second antibody alone or FITC-BSA to control cells.

Collagen is Rapidly Internalized by Endo180 into Early Endosomes and Subsequently Transported to Lysosomes

Endo180 is rapidly and constitutively internalized from the cell surface, cycled through early endosomes, and returned to the plasma membrane (Isacke et al., 1990; Howard and Isacke, 2002). To examine the intracellular trafficking of collagens, pulse chase experiments in conjunction with confocal microscopy were undertaken using the transfected MCF-7 cells. For these experiments, OG-gelatin was bound to the cells at 4°C to prevent ligand internalization. Excess unbound gelatin was removed by washing, and the cells were either fixed (time 0) or warmed to 37°C for up to 4 h. At the end of the experiment cells were stained with antibodies against Endo180 or the lysosomal protein LAMP1. After binding at 4°C, OG-gelatin was restricted to the cell surface in both wild-type Endo180-expressing cells (Figure 8A) and Endo180(Ala1468/Ala1469)-expressing cells (our unpublished results). In cells in which an anti-Endo180 mAb was incubated together with the OG-gelatin to stain cell surface Endo180, colocalization of ligand and receptor in a punctate pattern typical of clathrin-coated pits was observed (Figure 8A, top panel).

In parallel samples in which the cells were permeabilized before staining, a characteristic strong early endosomal staining of Endo180 was observed but no internalized gelatin was detected (Figure 8A, bottom panel). After a chase period of 5 min at 37°C the cell surface localized gelatin had largely disappeared and instead was found in fairly homogenous vesicular structures throughout the cytoplasm. Almost all of the internalized gelatin appeared in vesicles that were costained for Endo180 (Figure 8B top panel), and no gelatin was detected in lysosomal compartments as identified with the anti-LAMP1 mAb (Figure 8B, bottom panel). An identical pattern was observed with OG-collagen IV (Figure 8B, top panel and inset), demonstrating that Endo180 is able to mediate early endosomal delivery of native as well as denatured collagen. After 20 min chase the gelatin-containing vesicles became more concentrated to a perinuclear localization and showed no colocalization with either the Endo180-positive early endosomes or LAMP1-positive lysosomes (our unpublished results). This indicates that the association between Endo180 and gelatin is transient and that the collagenous ligand is rapidly transferred to Endo180-negative late endosomal compartments. Because no reduction in Endo180 staining was observed in these cells, it is likely that this receptor is recycled to the plasma membrane.

Over the next few hours, the distribution of internalized gelatin changed dramatically. First, the amount of internalized gelatin was variable with many cells having only very low levels of fluorescence. Second, in cells where gelatin could be readily detectable, it was predominantly localized in less abundant but larger and more heterogeneous vesicles, many of which had a typical ring-like LAMP1 staining (Figure 8C, bottom panel and inset). However, it should be noted that the overlap between gelatin and LAMP1 at 4 h was not complete, and a significant number of gelatin-positive vesicles were neither stained with LAMP1 nor with Endo180 antibodies (Figure 8C, top and bottom panels). In the Endo180(Ala1468/Ala1469) transfected cells, even after 4 h at 37°C, OG-gelatin and OG-collagen IV were still detected at the cell surface, and no internalized ligand was observed (our unpublished results).

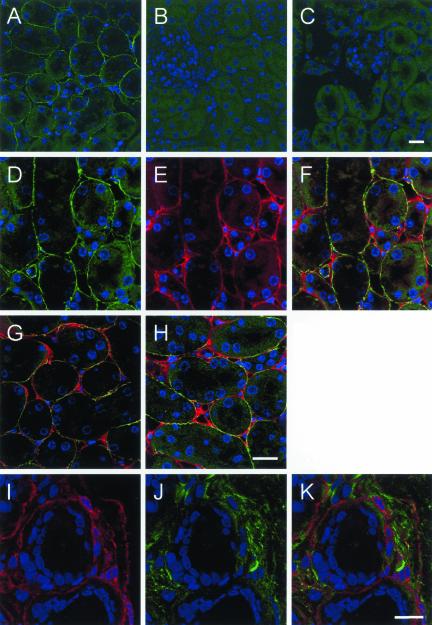

Endo180 Binds Native Collagens

The results presented so far have demonstrated that Endo180, either endogenous or transfected, can act as a receptor for commercially obtained solubilized collagens. To confirm that Endo180 can interact with native collagens, tissue sections were probed with the Endo180ΔCTLD5–8-Fc chimera. Sections from murine kidney were used in this analysis because it had previously been demonstrated that Endo180 expression in this tissue was restricted to the interstitial fibroblasts and that the epithelial cells were receptor negative (Isacke et al., 1990). Similarly, the distribution of collagens in the kidney has been well documented (Roll et al., 1980; Martinez-Hernandez et al., 1982; Yoshioka et al., 1990). Probing these sections with the Endo180ΔCTLD5–8-Fc chimera revealed that ligand binding was localized to the renal interstitium in the cortex, with no staining within the tubules (Figure 9A). As a control, no staining was observed in parallel sections where the Endo180-Fc chimera was replaced with human IgG (our unpublished results). Binding of the Endo180-Fc fusion protein was blocked by preincubation with collagen I (Figure 9B) or by pretreatment of the sections with collagenase (Figure 9C), indicating that the predominant tissue staining observed with soluble Endo180 constructs results from binding to native collagens. This was further confirmed by the strong codistribution of Endo180ΔCTLD5–8-Fc with fibrillar collagen I in the interstitial stroma (Figure 9, D–F). Similarly, there was a considerable degree of overlap in staining between the Endo180-Fc chimera with both the basement membrane collagen IV and the interstitial collagen V (Figure 9, G and H). Finally, to examine the distribution of Endo180 and collagens in vivo, sections of human breast were doubled labeled with anti-Endo180 mAb A5/158 and anti-collagen I antibody (Figure 9, I–K). Similar to the distribution in the kidney (Isacke et al., 1990), Endo180 is not expressed on the luminal or myoepithelial cells lining the breast ducts and lobules but is strongly expressed by stromal fibroblasts. The Endo180-positive intralobular fibroblasts project extensions to essentially encompass the ducts and lobules (Figure 9I) and contact both the collagen IV containing basement membrane (our unpublished results) and interstitial collagen I–containing matrix (Figure 9J). Similarly, elongated Endo180-positive interlobular fibroblasts are observed aligned with the collagen I containing fibers.

Figure 9.

Distribution of Endo180 and Endo180 ligand in vivo. (A–H) Paraformaldehyde fixed murine kidney sections, 25 μm, were probed with (A) Endo180ΔCTLD5–8-Fc followed by FITC anti-human Fc or (B) Endo180ΔCTLD5–8-Fc preincubated with collagen I. (C) Binding of Endo180ΔCTLD5–8-Fc to sections that had been pretreated with collagenase. (D–F) Sections that were incubated with Endo180ΔCTLD5–8-Fc followed by FITC anti-human Fc (green) and then with anti-collagen antibody followed by Alexa555 anti-rabbit Ig (red). Nuclei were counterstained with TO-PRO-3 (blue). (D) Endo180ΔCTLD5–8-Fc; (E) anti-collagen I; (F) merged image. (G) Merged image of Endo180ΔCTLD5–8-Fc and anti-collagen IV; (H) merged image of Endo180ΔCTLD5–8-Fc and anticollagen V. (I–K) Human breast cyrosections, 7 μm, were fixed and probed with (I) anti-Endo180 mAb A5/158 and Alexa555 anti-mouse Ig, followed by (J) anti-collagen I and Alexa488 anti-rabbit Ig. (K) Merged imaged. Bar, 20 μm.

DISCUSSION

In in vitro assays Endo180 binds gelatin and collagens I, II, IV, and V, and because the binding of gelatin and collagen both to soluble and cellular Endo180 can be cross-competed, it suggests that there is a common binding site for these ligands. Within the limits of these assays, it was observed that Endo180 bound more efficiently to gelatin than to collagen. The reason for this is not known but it may reflect a higher affinity of Endo180 for denatured collagens or simply the availability of more Endo180 binding sites in gelatin. Within Endo180, the gelatin/collagen-binding site has been localized to a fragment containing the N-terminal cysteinerich, FNII and CTLD1 domains and given that this FNII domain has sequence conservation with other collagen-binding FNII domains, we predict that it is this domain that is primarily responsible for the interaction with ligand. In support of this, cells expressing an Endo180 mutant in which the three N-terminal domains have been deleted show a collagen-binding and internalization defect (East et al., 2003). The principal difference from other gelatin/collagen-binding proteins is that Endo180 only contains a single FNII domain. In fibronectin, the 42-kDa gelatin binding fragment (6F11F22F27F18F19F1) contains two FNII domains, 1F2 and 2F2. Mapping of the gelatin-binding site within this fragment produced conflicting results (Owens and Baralle, 1986; Ingham et al., 1989; Skorstengaard et al., 1994; Pickford et al., 2001), most probably because the 6F11F22F2 region forms a hairpin loop with extensive interaction between the 6F1 and 2F2 domains (Pickford et al., 2001) and as a consequence, loss of neighboring domains or expression of individual domains would disrupt the FNII domain structure and hence the collagen-binding properties. Moreover, in a recent study, each of the six domains within the gelatin-binding fragment were deleted either alone or in combination. Interestingly all six domains were shown to contribute to ligand-binding affinity, suggesting that the role of domain:domain interactions extends beyond the 6F11F22F2 region (Katagiri et al., 2003). In MMP2 each of the three FNII domains can bind to gelatin in isolation, although with variable affinity (Collier et al., 1992). Again fragments containing all three tandem FNII domains show significantly stronger interaction than each one individually, indicating a cooperative binding activity (Banyai et al., 1994). These observations raise the question as to how the single Endo180 FNII domain might mediate high-affinity collagen binding. Sequence analysis reveals that the Endo180 FNII domain has conserved the N-terminal extension, which in the fibronectin 1F2 domain functions to bring the N- and C-termini into close proximity (Pickford et al., 1997, 2001), and single-particle electron microscopy studies have demonstrated that in Endo180 the FNII domain is intimately associated with adjacent cysteine-rich and CTLD1 domains (Rivera-Calzada et al., 2003). This three-dimensional arrangement may function to stabilize the interaction with collagen. In support of a role of CTLD1 in maintaining the correct Endo180 confirmation, we find that Endo180-Fc constructs containing only the cysteine-rich and FNII domain are unstable. Furthermore, Endo180 is constitutively recruited into clathrin-coated pits on the cell surface (Isacke et al., 1990), and therefore clustering of multiple Endo180 receptors may also enhance collagen binding.

Within its cytoplasmic domain, Endo180 contains a dihydrophobic endocytosis motif that is essential for the constitutive recruitment of this receptor into plasma membrane clathrin-coated pits. This is followed by rapid recruitment into the early endosomes and recycling back to the plasma membrane (Howard and Isacke, 2002). Such receptors typically internalize cargo that dissociates in the low pH endosomal environment and is subsequently targeted to the degradative compartments in the cell (Mellman, 1996; Gruenberg, 2001). Here we demonstrate that the constitutive endocytic property of Endo180 results in receptor:collagen complexes being rapidly internalized (<5 min) into early endosomes. As a consequence, cells expressing an Endo180 nonendocytic mutant are able to bind to, but not mediate uptake of, collagens. After delivery to the early endosomes, the collagenous cargo are seen to move quickly (<20 min) to an Endo180-negative compartment and by 1 h to be identified in LAMP1-positive degradative lysosomes. The absence of Endo180 colocalized with collagen in the later compartments indicates that the receptor is recycled ligand-free back to the plasma membrane.

In addition to collagens, Endo180 has been demonstrated to have two other binding activities. First, Endo180 can form a trimolecular cell surface complex with prouPA and uPAR (Behrendt et al., 2000). The uPA/uPAR system is involved in a wide variety of vital cellular proteolytic and signaling functions ranging from cell adhesion and migration to angiogenesis and extracellular matrix remodeling (Preissner et al., 2000; Mazar, 2001). Because uPAR is a glycosylphosphatidyl inositol (GPI)-linked receptor, it requires associated receptors such as Endo180 to mediate intracellular signaling and/or regulate cell surface expression. The ability of collagen V to prevent formation of this trimolecular complex indicates a role for the Endo180 FNII domain in the interaction with uPA/uPAR and additionally suggests that there may be functional interplay between Endo180's role as a collagen receptor and a uPAR-associated protein. For example, it will be interesting to determine whether the interaction of Endo180 with uPA/uPAR leads to localized uPA-mediated activation of plasminogen and subsequent degradation of matrix components, including collagens, which could then be cleared from the microenvironment by Endo180-mediated endocytosis. Second, Endo180 is a functional C-type lectin showing Ca2+-dependent binding to mannose, fucose, and N-acetylglucosamine, and this binding typical of mannose-specific C-type lectin domains has been localized to Endo180 CTLD2 (East et al., 2002). To date, physiological glycosylated ligands have not been identified, but again the relatively close proximity of the FNII and CTLD2 domains may result in competitive ligand interactions.

Importantly, the studies described here demonstrate that Endo180 is not only a receptor for commercially obtained collagens as soluble Endo180 extracellular domain expressed in mammalian cells is able to interact with native collagens in tissue sections. This raises the questions as to what function Endo180 might have as a collagen receptor in vivo. Endo180 is an endocytic receptor and the immunofluorescence data presented here indicates that internalized collagens are taken up via the clathrin-coated pits into the early endosomes rather than by a phagocytic route. Consequently it would be anticipated that uptake of collagens would involve degraded fragments or unincorporated collagens rather than intact collagen fibrils, which would be too large for the size restricted clathrin-coated vesicles. Endo180 does not have intrinsic collagenase activity, suggesting it would act in concert with proteases in the remodeling of the matrix and/or to remove unwanted collagens before their incorporation into the fibrils, thereby allowing proper assembly of the matrix components. Although further studies will be required to understand the balance between Endo180's role as a binding vs. internalization receptor, it is of note that Endo180 is predominantly expressed on stromal fibroblasts and in sites of embryonic and neonatal chondrogenic and osteogenic activity (Isacke et al., 1990; Wu et al., 1996; Sheikh et al., 2000; Engelholm et al., 2001). This tissue distribution reflects cells involved in active matrix deposition and remodeling, and moreover, Endo180 is highly up-regulated on angiogenic compared with normal endothelial cells (St. Croix et al., 2000) and on stromal fibroblasts and myoepithelial cells in breast tumors (Schnack Nielsen et al., 2002), where increased collagen catabolism is required. Together these data implicate a physiological role for Endo180 in the regulation of the extracellular matrix, both in normal tissue maintenance and as a component of disease progression.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dave Robertson for extensive help with the confocal microscopy, Rick Thorne for his help with the image analysis, Ian Titley for his help with FACS sorting, Maria Lelekakis and Afshan McCarthy for help with the tissue staining, and Justin Sturge and Lucy East for comments on the manuscript. This work was supported by funding from Breakthrough Breast Cancer Research and The Wellcome Trust.

DOI:10.1091/mbc.E02-12-0814.

NOTE ADDED IN PROOF

Since submission of this manuscript, two independent reports have demonstrated that fibroblasts from mice with a targeted Endo180 deletion show a collagen-binding defect (East et al., 2003; Engelholm et al., 2003).

References

- Arora, P.D., Manolson, M.F., Downey, G.P., Sodek, J., and McCulloch, C.A. (2000). A novel model system for characterization of phagosomal maturation, acidification, and intracellular collagen degradation in fibroblasts. J. Biol. Chem. 275, 35432–35441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banyai, L., Tordai, H., and Patthy, L. (1994). The gelatin-binding site of human 72 kDa type IV collagenase (gelatinase A). Biochem. J. 298(Pt 2), 403–407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Behrendt, N., Jensen, O.N., Engelholm, L.H., Mortz, E., Mann, M., and Dano, K. (2000). A urokinase receptor-associated protein with specific collagen binding properties. J. Biol. Chem. 275, 1993–2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collier, I.E., Krasnov, P.A., Strongin, A.Y., Birkedal-Hansen, H., and Goldberg, G.I. (1992). Alanine scanning mutagenesis and functional analysis of the fibronectin-like collagen-binding domain from human 92-kDa type IV collagenase. J. Biol. Chem. 267, 6776–6781. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis, G.E. (1992). Affinity of integrins for damaged extracellular matrix: alpha v beta 3 binds to denatured collagen type I through RGD sites. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 182, 1025–1031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- East, L., and Isacke, C.M. (2002). The mannose receptor family. Biochem. Biophys. Acta 1572, 364–386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- East, L., McCarthy, A., Wienke, D., Sturge, J., Ashworth, A., and Isacke, C.M. (2003). A targeted deletion in the endocytic receptor gene Endo180 results in a defect in collagen uptake. EMBO Rep. 4, 710–716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- East, L., Rushton, S., Taylor, M.E., and Isacke, C.M. (2002). Characterization of sugar binding by the mannose receptor family member, Endo180. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 50469–50475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engelholm, L.H. et al. (2001). The urokinase plasminogen activator receptor-associated protein/endo180 is coexpressed with its interaction partners urokinase plasminogen activator receptor and matrix metalloprotease-13 during osteogenesis. Lab. Invest. 81, 1403–1414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engelholm, L.H. et al. (2003). uPARAP/Endo180 is essential for cellular uptake of collagen and promotes fibroblast collagen adhesion. J. Cell Biol. 160, 1009–1015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Everts, V., Beertsen, W., and Tigchelaar-Gutter, W. (1985). The digestion of phagocytosed collagen is inhibited by the proteinase inhibitors leupeptin and E-64. Coll. Relat. Res. 5, 315–336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eyre, D.R. (1980). Collagen: molecular diversity in the body's protein scaffold. Science 207, 1315–1322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gruenberg, J. (2001). The endocytic pathway: a mosaic of domains. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2, 721–730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hellevik, T., Bondevik, A., and Smedsrod, B. (1996). Intracellular fate of endocytosed collagen in rat liver endothelial cells. Exp. Cell Res. 223, 39–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howard, M.J., and Isacke, C.M. (2002). The C-type lectin receptor Endo180 displays internalization and recycling properties distinct from other members of the mannose receptor family. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 32320–32331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ingham, K.C., Brew, S.A., and Migliorini, M.M. (1989). Further localization of the gelatin-binding determinants within fibronectin. Active fragments devoid of type II homologous repeat modules. J. Biol. Chem. 264, 16977–16980. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isacke, C.M., van der Geer, P., Hunter, T., and Trowbridge, I.S. (1990). p180, a novel recycling transmembrane glycoprotein with restricted cell type expression. Mol. Cell. Biol. 10, 2606–2618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johansson, N., Ahonen, M., and Kahari, V.M. (2000). Matrix metalloproteinases in tumor invasion. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 57, 5–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katagiri, Y., Brew, S.A., and Ingham, K.C. (2003). All six modules of the gelatin-binding domain of fibronectin are required for full affinity. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 11897–11902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lauer-Fields, J.L., Juska, D., and Fields, G.B. (2002). Matrix metalloproteinases and collagen catabolism. Biopolymers 66, 19–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee, W., Sodek, J., and McCulloch, C.A. (1996). Role of integrins in regulation of collagen phagocytosis by human fibroblasts. J. Cell. Physiol. 168, 695–704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leppert, D., Lindberg, R.L., Kappos, L., and Leib, S.L. (2001). Matrix metalloproteinases: multifunctional effectors of inflammation in multiple sclerosis and bacterial meningitis. Brain Res. Rev. 36, 249–257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez-Hernandez, A., Gay, S., and Miller, E.J. (1982). Ultrastructural localization of type V collagen in rat kidney. J. Cell Biol. 92, 343–349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayne, R., and Brewton, R.G. (1993). New members of the collagen superfamily. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 5, 883–890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazar, A.P. (2001). The urokinase plasminogen activator receptor (uPAR) as a target for the diagnosis and therapy of cancer. Anti-cancer Drugs 12, 387–400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGaw, W.T., and Ten Cate, A.R. (1983). A role for collagen phagocytosis by fibroblasts in scar remodeling: an ultrastructural stereologic study. J. Invest. Dermatol. 81, 375–378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mellman, I. (1996). Endocytosis and molecular sorting. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 12, 575–625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Owens, R.J., and Baralle, F.E. (1986). Mapping the collagen-binding site of human fibronectin by expression in Escherichia coli. EMBO J. 5, 2825–2830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez-Tamayo, R. (1978). Pathology of collagen degradation. A review. Am. J. Pathol. 92, 508–566. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pickford, A.R., Potts, J.R., Bright, J.R., Phan, I., and Campbell, I.D. (1997). Solution structure of a type 2 module from fibronectin: implications for the structure and function of the gelatin-binding domain. Structure 5, 359–370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pickford, A.R., Smith, S.P., Staunton, D., Boyd, J., and Campbell, I.D. (2001). The hairpin structure of the (6)F1(1)F2(2)F2 fragment from human fibronectin enhances gelatin binding. EMBO J. 20, 1519–1529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preissner, K.T., Kanse, S.M., and May, A.E. (2000). Urokinase receptor: a molecular organizer in cellular communication. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 12, 621–628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prockop, D.J., and Kivirikko, K.I. (1995). Collagens: molecular biology, diseases, and potentials for therapy. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 64, 403–434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rivera-Calzada, A., Robertson, D., MacFayden, J.R., Boskovic, J., Isacke, C.M., and Llorca, O. (2003). Three-dimensional interplay among the ligand binding domains of the uPAR-associated protein, Endo180. EMBO Rep. (Epub ahead of print). Available at: http://emboreports.npgjournals.com. Accessed August 11, 2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Roll, F.J., Madri, J.A., Albert, J., and Furthmayr, H. (1980). Codistribution of collagen types IV and AB2 in basement membranes and mesangium of the kidney. an immunoferritin study of ultrathin frozen sections. J. Cell Biol. 85, 597–616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schnack Nielsen, B., Rank, F., Engelholm, L.H., Holm, A., Dano, K., and Behrendt, N. (2002). Urokinase receptor-associated protein (uP-ARAP) is expressed in connection with malignant as well as benign lesions of the human breast and occurs in specific populations of stromal cells. Int. J. Cancer 98, 656–664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheikh, H., Yarwood, H., Ashworth, A., and Isacke, C.M. (2000). Endo180, an endocytic recycling glycoprotein related to the macrophage mannose receptor is expressed on fibroblasts, endothelial cells and macrophages and functions as a lectin receptor. J. Cell Sci. 113, 1021–1032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skorstengaard, K., Holtet, T.L., Etzerodt, M., and Thogersen, H.C. (1994). Collagen-binding recombinant fibronectin fragments containing type II domains. FEBS Lett. 343, 47–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smedsrod, B., Johansson, S., and Pertoft, H. (1985). Studies in vivo and in vitro on the uptake and degradation of soluble collagen alpha 1(I) chains in rat liver endothelial and Kupffer cells. Biochem. J. 228, 415–424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smedsrod, B., Pertoft, H., Gustafson, S., and Laurent, T.C. (1990). Scavenger functions of the liver endothelial cell. Biochem. J. 266, 313–327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- St. Croix, B., Rago, C., Velculescu, V., Traverso, G., Romans, K.E., Montgomery, E., Lal, A., Riggins, G.J., Lengauer, C., Vogelstein, B., and Kinzler, K.W. (2000). Genes expressed in human tumor endothelium. Science 289, 1197–1202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steffensen, B., Wallon, U.M., and Overall, C.M. (1995). Extracellular matrix binding properties of recombinant fibronectin type II-like modules of human 72-kDa gelatinase/type IV collagenase. High affinity binding to native type I collagen but not native type IV collagen. J. Biol. Chem. 270, 11555–11566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Svoboda, E.L., Shiga, A., and Deporter, D.A. (1981). A stereologic analysis of collagen phagocytosis by fibroblasts in three soft connective tissues with differing rates of collagen turnover. Anat. Rec. 199, 473–480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vogel, W., Brakebusch, C., Fassler, R., Alves, F., Ruggiero, F., and Pawson, T. (2000). Discoidin domain receptor 1 is activated independently of beta(1) integrin. J. Biol. Chem. 275, 5779–5784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vogel, W.F., Aszodi, A., Alves, F., and Pawson, T. (2001). Discoidin domain receptor 1 tyrosine kinase has an essential role in mammary gland development. Mol. Cell. Biol. 21, 2906–2917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu, K., Yuan, J., and Lasky, L.A. (1996). Characterization of a novel member of the macrophage mannose receptor type C lectin family. J. Biol. Chem. 271, 21323–21330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshioka, K., Tohda, M., Takemura, T., Akano, N., Matsubara, K., Ooshima, A., and Maki, S. (1990). Distribution of type I collagen in human kidney diseases in comparison with type III collagen. J. Pathol. 162, 141–148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]