Abstract

The dynamics of Clostridium botulinum neurotoxins (BoNTs) protein-translocation across membranes was investigated by using a single molecule assay with millisecond resolution on excised patches of neuronal cells. Translocation of BoNT/A light chain (LC) by heavy chain (HC) was observed in real time as an increase of channel conductance: the HC channel is occluded by the LC during transit, then unoccluded after completion of translocation and release of LC-cargo. We identified an entirely unknown succession of intermediate conductance stages during LC translocation. For the single-chain BoNT/E, by contrast to the di-chain BoNT/A, we demonstrate that productive translocation requires proteolysis of the LC cargo from the HC chaperone. We propose a model for the set of protein–protein interactions between translocase and cargo at each step of translocation that supports the notion of an interdependent, tight interplay between the HC chaperone and the LC cargo preventing LC aggregation and dictating the outcome of translocation: productive passage of cargo or abortive channel occlusion by cargo.

Keywords: channels, chaperones, protein translocation, synaptic exocytosis

Botulinum neurotoxin (BoNT) is considered the most potent toxin known; it is the causative agent of botulism, a neuroparalytic illness (1), and a major bioweapon (2). Clostridium botulinum, a spore-forming, obligate anaerobic bacterium, secretes seven BoNT isoforms designated A to G. All isoforms, together with the related tetanus neurotoxin (TeNT) secreted by Clostridium tetani, are Zn2+-endoproteases that block synaptic exocytosis by cleaving SNARE (soluble NSF attachment protein receptor) proteins (3–8). Assembly of the SNARE core complex is a key step preceding fusion of synaptic vesicles with the neuronal plasma membrane (5, 6, 9).

How do the proteases reach their cytosolic substrates? BoNTs have two chains linked by a disulfide bond: an N-terminal light chain (LC) of ≈50 kDa and a heavy chain (HC) of ≈100 kDa; structurally, BoNT consists of three domains (6, 10–12): the catalytic LC and the HC encompassing the translocation domain (the N-terminal half) and the receptor-binding domain (the C-terminal half). BoNTs enter sensitive cells by means of receptor-mediated endocytosis (6, 13, 14). The BoNT receptor-binding module establishes the cellular specificity mediated by its high affinity interaction with a surface protein receptor, SV2 for BoNT/A (15, 16) and synaptotagmins I and II for BoNT/B and BoNT/G (17), and a ganglioside (GT1B) coreceptor (15–18). Exposure of the BoNT–receptor complex to the acidic milieu of endosomes (13, 14, 19, 20) results in a major conformational change and the insertion of the HC into the endosomal bilayer membrane.

Early studies have shown that BoNT HC forms channels in lipid bilayers (21–23) and PC12 cells (24), predominantly under acidic conditions and only after chemical reduction. These results were the cornerstone to view the BoNT translocation domain as the conduit for the passage of the enzymatic module from the interior of the endosome into the cytosol allowing contact between the protease and the SNARE substrates (6, 13, 23). Previously, we discovered that the HC of BoNT/A acts as both a channel and a transmembrane chaperone for the LC to ensure a translocation competent conformation during its transit from the acidic endosome into the cytosol (25). These findings provided compelling evidence of retrieval of endopeptidase activity of BoNT LC in the trans-compartment only after productive translocation across bilayers (25). The beginning and the end of the translocation step are known; however the intricacies of the translocation process remain unknown.

Here, the dynamics of protein translocation focusing on the interactions between the HC channel/chaperone and its LC cargo were probed under conditions that closely emulate those prevalent at the endosome. We developed an assay in neuronal cells to monitor interactions between the HC and the LC during translocation with single molecule sensitivity. The system allows us to selectively probe the accessibility of the LC by its interaction with a specific monoclonal antibody or with proteases at different stages during translocation from the acid to the neutral compartment. We characterized in real time the BoNT channel and chaperone activities to determine the constraints for LC unfolding and refolding at the entry and exit interfaces of the chaperone. This analysis led us to uncover an unknown succession of clear intermediate states in the course of LC translocation and to dissect a single translocation event into its component parts namely, entry, a series of transfer steps, and exit. These findings indicate that BoNT translocation involves an acid pH-induced membrane insertion step coupled to LC unfolding and entry into the HC chaperone/channel, LC protein conduction through the HC channel, and subsequent release of the LC cargo from chaperone by reduction of the disulfide bridge concomitant with LC refolding at the cytosol.

Results

Holotoxin Channels Display a Time-Dependent Conductance Increase.

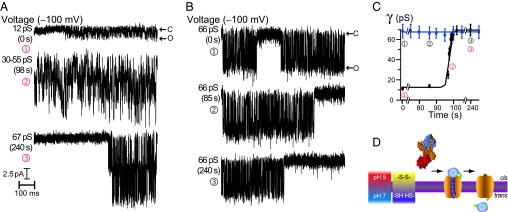

We developed a translocation assay at the single channel level in excised patches of BoNT/A-sensitive Neuro 2A cells to investigate the dynamics of protein translocation focusing on the interactions between the HC channel/chaperone and its LC cargo. This highly sensitive assay can monitor the activity of BoNT at the single molecule level, and it is specific because no channel activity is detected in these cells in the absence of toxin. Channel activity was recorded on excised patches of Neuro 2A cells exposed to purified BoNT/A holotoxin [supporting information (SI) Fig. 6] only under conditions that emulate the pH and redox gradient across endosomes, i.e., pH 5.3 on the cis- compartment containing BoNT and pH 7.0 on the trans-compartment supplemented with the membrane nonpermeable reductant Tris-(2-carboxyethyl) phosphine (TCEP). Without these pH and redox gradients across the membrane, no channel activity is recorded (25). Under these conditions, the toxin changes from a water soluble di-chain protein to a membrane inserted channel which can be assayed by monitoring the sodium conductance of the channel (Fig. 1A and SI Fig. 7A). The time course of change of the single channel conductance (γ) after insertion of holotoxin into the membrane displays discrete transient intermediate conductances before achieving a γ of 67.1 ± 2.0 pS, corresponding to transitions from the closed to the open state. Once plateaued, γ remains constant throughout the typically 1 h experiment, as calculated from the current amplitude histograms (SI Fig. 7B and SI Table 1). In this experiment, two holotoxin channels were inserted into the membrane, as shown in the second and third traces. BoNT channel activity occurs in bursts and only opens at negative voltages (26). Trace ② displays holotoxin channels undergoing a continuous increase in γ and reaching a stable value by trace ③. In contrast, the isolated HC exhibits a constant γ = 66.4 ± 2.4 pS over the entire experiment regardless of the applied voltage (Fig. 1B and SI Fig. 7 B and C). This invariant γ is a signature of the HC channel, and is characteristic of holotoxin channels after completion of a single increasing conductance event. The half-time for completion of such event, estimated from the abrupt transition from low to high conductance is ≈10 s (Fig. 1C) with an initial γ ≅ 13 pS and a final, constant γ ≅ 67 pS characteristic of the unoccluded HC after event completion. We interpret the progressive, stepwise increase in channel conductance with time as the progress of LC translocation during which the HC channel initially conducts Na+ and partially unfolded LC, detected as channel block. After translocation is complete the channel is unoccluded (Fig. 1D).

Fig. 1.

BoNT/A holotoxin and HC channels in excised patches of Neuro 2A cells. Single-channel currents for holotoxin (A) and HC (B) at −100 mV and the indicated times. Holotoxin (A) and HC (B) channel activity begins 20 min and 21 min after GΩ seal formation. The letters C and O denote the closed and open states. (C) Time course of γ change of holotoxin (black circle) and HC (blue circle) for the representative experiments (average N per data point = 570). γ values associated with raw data (colored numbers) from A and B are indicated. (D) Structure of BoNT/A holotoxin (10). Shown are LC (purple), translocation domain (orange), and receptor binding domain (red) before insertion in the membrane (gray bar with magenta boundaries); then is shown a schematic of the membrane inserted BoNT/A during translocation of the LC (purple) through the HC channel (orange) with intact disulfide bridge (green) while located in the cis-compartment. Conventions hold for all figures.

Holotoxin Channels Exhibit Discrete Intermediate Conductances Which Reflect Permissive Stages During Translocation.

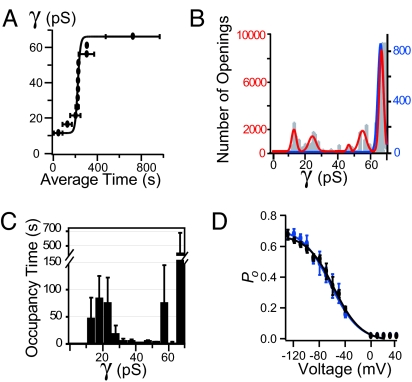

To rigorously characterize the translocation process, the time course of γ change for six separate experiments was analyzed. The average time course of γ change after insertion of holotoxin into membranes reaches a plateau after ≅ 260 s (Fig. 2A). A succession of discrete transient intermediate conductances, each defined as a minimum of 500 events, is discerned at γ ≅ 13 pS, 24 pS, 47 pS, and 55 pS before entering the stable γ of 67 pS (Fig. 2 B and C). This pattern of channel activity characteristic of holotoxin (Fig. 1A) allows us to operationally define three states of the BoNT channel. First, a closed state, and second, an “occluded state” with the partially unfolded LC trapped within the channel during the translocation process. This occluded state is identified as a set of intermediate conductances corresponding to transitions between the closed state and several blocked open states. Third, an “unoccluded state” visible upon completion of translocation and release of the LC associated to transitions between the closed state and the fully open state.

Fig. 2.

Analysis of BoNT/A holotoxin and HC channels in Neuro 2A cells. (A) Average time course of channel γ change for holotoxin (n = 6, average N per data point = 4,650). (B) γ amplitude histogram (gray) and Gaussian fit calculated from the combined data set of six separate BoNT/A holotoxin experiments (red) and one representative BoNT/A HC experiment (blue). BoNT/A HC has a γ = 66.4 ± 2.4 pS (N = 10,200); holotoxin has γ values = 12.6 ± 2.0 pS, 24.1 ± 3.4 pS, 46.8 ± 1.6 pS, 55.3 ± 3.4 pS (N = 55,890). The endpoint γ = 67.1 ± 2.0 pS is equivalent to that of HC. (C) Average occupancy time of conductance states of BoNT/A holotoxin (n = 6, average N per data point = 4,650). (D) Po as a function of voltage for holotoxin (black circle) (V½ = −58.3 ± 1.7 mV) and for HC (blue circle) (V½ = −63.4 ± 2.4 mV) (3 ≤ n ≤ 11 per data point; average N per data point = 2,630).

The endpoint γ for holotoxin (67 pS) and HC (66 pS) channels exhibit similar characteristics: both molecular entities display an indistinguishable voltage dependence, opening only at negative voltages; V½, the voltage at which Po = 0.5, is ≈ –60 mV (Fig. 2D). This analysis substantiates the view of the HC channel as an endpoint achieved after completion of LC translocation through the HC channel, as observed in holotoxin channels (Fig. 1).

A LC Specific Antibody Arrests Translocation After Initiation of LC Entry into the HC Channel.

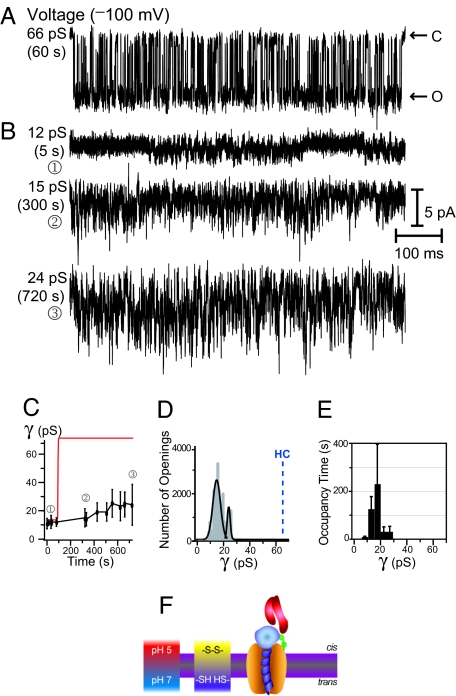

Is translocation affected by a LC which is tightly bound to a folded protein? To discern the underlying protein–protein interactions between BoNT/A LC and HC during translocation, we exploited the specificity of a monoclonal antibody generated against the BoNT/A LC. To test this model, Fab fragments were preincubated with BoNT/A holotoxin or HC (5:1 mole/mole) for 1 h at pH 7 before the translocation assay. This condition does not affect HC channel activity (Fig. 3A), however it transforms that of the holotoxin (Fig. 3B). Holotoxin channels are detected within a few minutes after patch excision albeit of lower conductance (≈15 pS and ≈24 pS), a feature which remains constant for the duration of the recording (Fig. 3B). The initial γs are comparable with those characteristic of the early intermediate γ states in unmodified holotoxin; however, instead of proceeding through the sequence of intermediates and ending with γ at 67 pS, the channels remain in the low γ states throughout the experiment (Fig. 3C). The second and third traces in Fig. 3B show multiple channels of low γ; in addition, the current transitions are faster and short-lived, giving the appearance of flickering between low and high γ states. This striking feature is characteristic of channel block (25).

Fig. 3.

LC/A translocation arrest by a LC/A specific Fab. Shown are single-channel currents for HC (A) and holotoxin (B) at −100 mV and the indicated times. HC (A) and holotoxin (B) channel activity begins 5 min after GΩ seal formation. (B) Trace-① displays the pattern of activity at the beginning of the record. Multiple channel insertions occur with time (traces② and ③). (C) Time course of holotoxin channel γ change (average N per data point = 600). Thin red line represents results for unmodified holotoxin/A. (D) γ amplitude histogram (gray) and Gaussian fit (black) with γ = 14.8 ± 4.1 pS and 24.0 ± 1.6 pS (N = 22,113). HC indicates the unoccluded HC conductance. (E) Average occupancy time of conductance states (n = 5, average N per data point = 5,170). (F) Schematic representation of BoNT/A holotoxin translocation arrested by Fab (red).

Analysis of five experiments indicates that under such conditions the channel preferentially resides in the 15 pS and 24 pS states (Fig. 3 D and E). These γ values approximate the two lowest conductance intermediate states observed for the early intermediates of the Fab-free holotoxin during translocation (Fig. 2B). We interpret these intermediates as early steps in translocation in which the HC has formed a channel that is partially occluded by the LC (Fig. 3F). Fab binding to the LC does allow channel formation and early translocation, stabilizing intermediate protein–protein interactions. However, by binding to the LC and inhibiting its unfolding, the Fab locks the channel and the LC in a translocating conformation that is irreversibly incomplete.

Productive Translocation Requires Proteolytic Cleavage of LC Cargo from HC Channel.

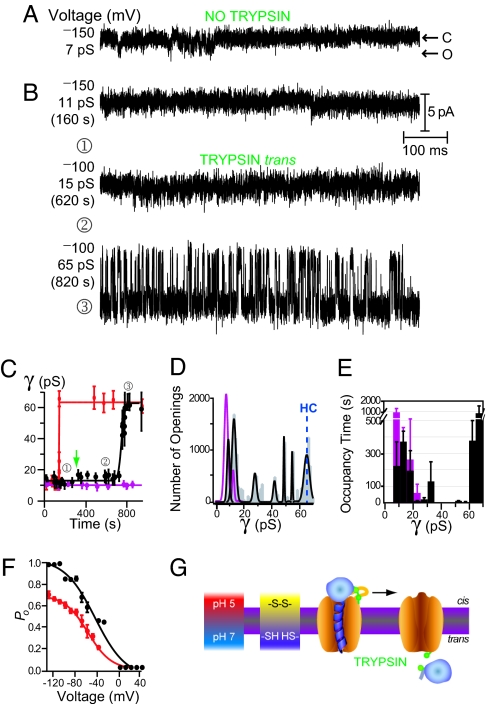

Our model predicts that a covalently linked, single-chain holotoxin should remain in a blocked state with the LC locked within the HC channel and not complete translocation. Channel formation and early intermediate steps would ensue; however, an arrested rather than a productive translocation event would be predicted to occur. An endogenous clostridial protease is known to “nick” BoNT/A between the LC and the HC producing the di-chain mature toxin. In contrast, BoNT/E is not cleaved before secretion and, therefore, a full length, single-chain protein is produced. Fig. 4A illustrates that BoNT/E holotoxin indeed forms channels; however, the channel persists in the low γ states similar to those seen during early steps of translocation in holotoxin BoNT/A (Fig. 2B). BoNT/E channel activity does not exhibit BoNT/A HC channel features, never reaching the γ ≅ 66 pS. This property provides a built-in assay to probe whether proteolytic cleavage of the LC anchor to the HC would allow for the completion of translocation. Trypsin is commonly used to “activate” BoNT/E in enzymatic assays of cleavage of its substrate, SNAP-25; this treatment proteolytically nicks the LC from the HC and enhances the intrinsically marginal protease activity of holotoxin/E (SI Fig. 6) (27, 28). As a control, we established that exposure of Neuro 2A cells to trypsin, in the absence of toxin, does not elicit channel activity. Next, we asked whether trypsin addition to Neuro 2A cells after detection of BoNT/E channel activity would alter the low γ pattern shown in Fig. 4A. Trypsin was added 300 s (Trace-②) after the onset of channel activity (Trace-①) (Fig. 4B). The channel remained in the low γ states displaying discrete intermediate conductances for ≈400 s, and then abruptly entered into the unoccluded state ≅ 65 pS, constant value for the remainder of the experiment (Trace-③). The time course of conductance change is illustrated in Fig. 4C; the green arrow indicates addition of the membrane impermeable trypsin to the trans-side and the results are depicted in black. By contrast to the sharp increment in conductance produced by trypsin addition, no increase in γ is detected for BoNT/E if trypsin is not added to the trans compartment (Fig. 4C): BoNT/E holotoxin channels remain in the low γ states for the entire duration of the experiments, consistent with the persistent occlusion of HC channel by the LC. Furthermore, trypsin-nicking of BoNT/E before exposure to the cells, equivalent to trypsin addition to the cis-side, evokes a pattern of channel activity indistinguishable to that produced by di-chain BoNT/A (Figs. 1 and 2 and SI Fig. 7); the results are shown in Fig. 4C (red) and SI Fig. 8.

Fig. 4.

The single-chain BoNT/E holotoxin requires proteolytic cleavage to complete translocation of LC. Shown are representative single-channel currents at the indicated voltages and times; consecutive voltage pulses applied to the two different patches. (A) Holotoxin channel activity begins 5 min (A) and 25 min (B) after GΩ seal formation. (B) Trypsin addition (4 mM) to the trans-side occurs at 300 s. (C) Time course of channel γ change of trypsin-nicked BoNT/E before exposure to the cells (red circle), single-chain holotoxin/E (pink circle), and single-chain holotoxin/E after trypsin addition to the trans-side (black circle) (green arrow) for representative experiments (average N per data point = 275). (D) γ amplitude histogram and Gaussian fit of single-chain holotoxin/E, γ = 7.7 ± 1.8 pS and 12.7 ± 1.0 pS; Gaussian fit illustrated in pink, data not shown (N = 10,840). Holotoxin/E, after trypsin addition to the trans-side, has γ = 9.3 ± 1.3 pS, 13.3 ± 2.0 pS, 28.4 ± 1.6 pS, 42.4 ± 1.3 pS, 49.2 ± 0.5 pS, 55.0 ± 0.5 pS, and 65.4 ± 2.8 pS; shown are raw data (gray) and Gaussian fit (black) (N = 19,431). (E) Average occupancy time of conductance states for trypsin-nicked holotoxin/E (black) and single-chain holotoxin/E (pink) (n = 4 for each experimental condition, average N per data point: single-chain holotoxin/E = 460, trans-trypsin nicked holotoxin/E = 1,470). (F) Po as a function of voltage for holotoxin/E (black circle) and holotoxin/A (red circle); V½ for holotoxin/E is −45.0 ± 5.4 mV (3 ≤ n ≤ 11 per data point; average N per data point = 2,275). (G) Schematic of single-chain holotoxin BoNT/E occluded channels, the subsequent cleavage of the LC from the HC by trypsin, and the consequent LC release into the neutral pH compartment.

Analysis of four separate experiments for single-chain BoNT/E demonstrates that, within minutes of trypsin addition to the trans-compartment, the BoNT/E channel displays a succession of discrete transient intermediate γ states associated to channel block by the LC at γ ≅ 9 pS, 13 pS, 28 pS, 42 pS, 49 pS, and 55 pS before entering the unoccluded state of 65 pS, inferred to be that characteristic of the HC after completion of LC translocation (Fig. 4D). The timing appears slower than for BoNT/A holotoxin translocation; this apparent delay arises because trypsin was not added until 300 s after the onset of channel activity to confirm that translocation completion requires trypsin addition. These γ values approximate most of the intermediate states displayed by holotoxin/A during translocation (Fig. 2); the intermediate states at γ ≅ 28 pS and 42 pS may be the result of translocating the uncleaved loop of BoNT/E through the channel. In contrast, the residency time in each intermediate state differs from BoNT/A: the occluded channel conductance intermediates with γ ≅ 9 pS, 13 pS, and 28 pS are more permissive (Fig. 4E). This result is consistent with the view that these low conductance states are stabilized by the LC trapped within the HC. BoNT/E channels recorded after addition of trypsin to the trans-side feature a finite γ ≅ 65 pS: these channels are indistinguishable to BoNT/A HC channels (Figs. 1B and 2 B and D) displaying similar γ and voltage dependence, consistent with the attainment of the unoccluded HC state by BoNT/E (Fig. 4F). Holotoxin/E exhibits a higher propensity to reside in the open state compared with holotoxin/A (Fig. 4B Bottom), and the V½ is right shifted by ≈ 15 mV to –45 ± 5 mV with respect to holotoxin/A (Fig. 4F).

The findings with single-chain BoNT/E holotoxin demonstrate that LC translocation can be observed as a succession of discrete transient intermediate conductances associated with channel block. Release of this block only occurs after the LC completes translocation from the cis- to the trans-compartment and is physically separated from the HC channel by both reduction of the disulfide bridge and cleavage of the siscile bond (Fig. 4G).

Discussion

Are LC Unfolding and Translocation Coupled?

It is remarkable that low γ intermediates were identified for all of the conditions in which holotoxins were examined. We infer that these intermediates, observed as occluded states, correspond to permissible chaperone-cargo conformations populated during translocation (Fig. 1). This view is in line with the time course of occurrence of the γ intermediates. Previous work demonstrated a tight correlation between the decrease in α-helical content of the LC at pH 5.0 with the occurrence of channel and protease activities of holotoxin; this finding necessarily constrains the LC-cargo to be either extended or α-helical segments to fit into a channel of ≈15 Å in diameter, as calculated from the γ of BoNT/A (25). We postulate that the residence time at each intermediate reflects the conformational changes of cargo within the chaperone pore and that these determine the efficiency and outcome of translocation. Within the occluded state, the frequency of occurrence of the lowest conductance intermediates (γ ≅ 12 pS and 20 pS) is higher, as determined by their individual occupancy times (Fig. 2C): the low conductance states exhibit the longest occupancy time, consistent with an energetic barrier associated with the initiation of LC unfolding, presumably into a molten globule state (29), at the onset of translocation, an entry event (Fig. 5, step 2). That γ values for unmodified holotoxin/A (Fig. 2) and holotoxin/A bound to the LC-specific Fab (Fig. 3) practically overlap, and for the Fab-arrested condition the pore occupancy for such intermediates predominates, argues in favor of this notion and is consistent with the arrest of translocation at the entry step in the process. However, Fab binding terminates the growing γ progress by trapping the LC and the HC channel in a translocating conformation that is irreversibly arrested (Fig. 3). By contrast, intermediates with γ values between 25 and 50 pS have shorter lifetimes, presumably a result of overcoming the activation energy (Fig. 5, step 3). This sequence of transfer steps leads to a transition into the final γ intermediate measured at γ ≅ 55 pS (Fig. 5, step 4). This last intermediate in the sequence (Fig. 2) is relatively long-lived at ≈75 s, plausibly limited by the refolding of the LC at the channel exit interface in the trans compartment and reduction of the disulfide bridge before final release from the HC channel, an exit event (Fig. 5, step 5). Thus, a single LC translocation involves an entry event, a series of transfer steps, and an exit event. The requirement for acid-induced unfolding and the timing correspond well with those reported for the translocation of the 263-residue N-terminal domain of anthrax lethal factor, the cargo, through the transmembrane pore formed by the protective antigen heptameric pore (30–32). Evidence for the importance of unfolding for efficient translocation and a propensity toward α-helical structure translocation was elegantly obtained for BoNT/D by Bade et al. (33) by using an entirely different experimental approach. Currently, there is no information about unfolding and refolding pathways; what can be said is that there is a trend to preserve partially unfolded, yet mobile, native-like regions.

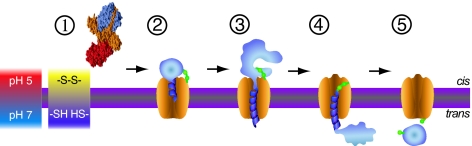

Fig. 5.

Sequence of events underlying BoNT LC translocation through the HC channel. Step 1, Crystal structure of BoNT/A holotoxin (10) before insertion in the membrane. Then is shown a schematic representation of the membrane inserted BoNT/A during an entry event (step 2), a series of transfer steps (steps 3 and 4), and an exit event (step 5), under conditions that recapitulate those across endosomes.

Release of Cargo from Chaperone Is Necessary for Productive Translocation.

The results obtained for BoNT/E provide compelling evidence for the requirement of cargo dissociation from chaperone as one of the final steps in the progress of translocation. The transformation of an occluded state characterized by low γ intermediates with prolonged pore occupancy into an unoccluded channel with γ ≈65 pS (Fig. 4) is unambiguous and leads to the conclusion that the chaperone-cargo anchor must be severed to complete productive translocation.

As demonstrated previously, the disulfide bridge linkage must also be severed to release the LC cargo after completion of translocation (25). Unreduced holotoxin/A (25) and holotoxin/E (Fig. 4) do not exhibit channel activity. Further, addition of TCEP only to the cis-compartment after acidification fails to evoke channel activity (25). This observation is indicative of disulfide shielding arising from the onset of the LC translocation through the HC channel. Thus, proteolytic cleavage of LC from HC and disulfide reduction during the exit event are both required for translocation.

Alternative Models to Protein Translocation.

The translocation model embodies the notion that the succession of discrete intermediate conductances reflects permissive stages during LC translocation. Alternatively, it is conceivable that the channel is a conductive oligomer resulting from the self-assembly of monomers with the intermediate conductances as reporters of the oligomerization process. Whereas the occurrence of oligomers was surmised from early images of BoNT/A incorporated into liposomes (34), the fact that the isolated HC displays a constant γ implies that this molecular entity is assembled immediately after membrane insertion. Together with evidence that growing conductance events in holotoxin (Figs. 2 and 4) lead to an end-point stable entity with characteristics equivalent to isolated HC argue against an oligomer. The single-chain BoNT/E data are inconsistent with HC oligomerization because the LC is protease protected until translocated across to the trans-side. The view that γ intermediates are only reporters of the refolding process is incompatible with both the BoNT/E and BoNT/A-Fab result. The regularity and discreteness of γ is opposite to the erratic fluctuations typical of bilayer dielectric core disturbances produced by surfactants, thus excluding unspecific perturbations.

The HC Channel in the Endosome After LC Translocation.

A feature of the BoNT channel, both for BoNT/A (Fig. 2D) and BoNT/E (Fig. 4F), is that it is closed at positive voltages under conditions in which the orientation and the magnitude of the pH gradient, as well as the polarity and magnitude of the membrane potential recapitulate those across endosomes: pH 5.3 and positive potential on the compartment containing the BoNT and pH 7.0 and negative potential on the opposite compartment. This attribute suggests that the BoNT HC channel would be closed in the endosome until it is gated by the LC to initiate its translocation across the membrane into the cytosol (Figs. 2D and 4F). After completion of LC translocation, the channel would be closed, precluding the passive dissipation of the electrochemical ionic gradients across endosomes. This notion is consistent with the fact that currents evoked by short pulses of negative potential were required to monitor channel activity; however, the voltage-dependence of translocation has yet to be explored. That channel activity has been documented for BoNT/A (22, 24–26), BoNT/E (this work and ref. 24), BoNT/B (23), BoNT/C (21) and tetanus neurotoxin (TeNT) (23, 35, 36), and protein translocation activity has been shown for BoNT/A (this work and ref. 25), BoNT/E (this work) and BoNT/D (33) points to the general validity of the proposed mechanism.

The HC Channel as a Chaperone for the LC Protease.

The interaction between an unfolded or partially folded LC embedded within the HC resembles the maintenance of partially folded polypeptides by chaperones. It is fitting to consider plausible similarities to these chaperones. The structures of protein-conducting channels of the Escherichia coli SecYEG bound to a translating ribosome (37), and the archaeon Methanococcus jannaschii SecYEβ (38) define blueprints for protein-conducting channels for which the underlying protein fold is a compact transmembrane α-helical bundle. Both structures suggest a resemblance to the occluded BoNT channel. These two structures outline the intricacies of the initial stages of protein translocation and are consistent with the occurrence of discrete transient intermediates involving extensive interactions between the chaperone and the cargo in a dynamic succession dictating the progress and directionality of translocation. Protein import in mitochondria and chloroplasts involves unfolded proteins (for review, see refs. 39–41). The inner mitochondrial membrane TIM23 translocase (42), the outer (Toc75) (43) and inner (Tic110) (44) chloroplast membrane translocases display pore diameters of ≈13 Å, ≈14 Å and ≈15 Å, respectively constraining the secondary structure of the precursor polypeptide cargos to be either extended or α-helical segments. An analogous requirement for unfolded cargo is required by β-barrel translocases: the protective antigen PA63 pore of anthrax toxin exhibits a central pore with a cross-section of ≈15 Å (32). Similar models have emerged from single channel measurements on the interactions between helical cargo peptides and the transmembrane β-barrel of the α-hemolysin protein pore (45). Compared with the molecular complexity of these protein translocases the BoNT protein highlights the simplicity of its modular design to achieve its exquisite activity. The analogy that emerges from the findings reported here for BoNT, a modular nanomachine in which one of its modules (the HC channel) operates as a specific protein translocating transmembrane chaperone for another of its modules (the LC protease) is more than coincidental and points to a fundamental common principle of molecular design.

Materials and Methods

Materials.

Unless otherwise specified, all chemicals were purchased from Sigma–Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). Purified native BoNT isoform A and E holotoxins and isoform A HC were from Metabiologics (Madison, WI) and the ING2 BoNT/A LC specific monoclonal antibody was kindly provided by J. Marks (University of California, San Francisco, CA). Di-chain BoNT/E holotoxin was generated by cleavage with trypsin (see SI Text for details).

Cell Culture and Patch Clamp Recordings.

Excised patches from Neuro 2A cells in the inside-out configuration were used as described in SI Text. Currents were recorded under voltage-clamp conditions by the application of consecutive voltage steps 800 ms in duration from +50 mV to −150 mV. All experiments were conducted at 22°C ± 2°C.

Solutions.

To emulate endosomal conditions, the trans-side (bath) solution contained 200 mM NaCl, 5 mM NaMOPS [3-(N-morpholino) propanesulfonic acid] (pH 7.0 with HCl), 0.25 mM TCEP, and 1 mM ZnCl2; the cis-side (pipet) solution contained 200 mM NaCl and 5 mM NaMES [2-(N-morpholino) ethanesulfonic acid] (pH 5.3 with HCl). See SI Text for details.

Data Analysis.

Analysis performed on single bursts of each experimental record. A single burst is defined as a set of openings and closings lasting ≥50 ms bounded by quiescent periods of ≥50 ms before and after. Only single bursts were analyzed because of the random duration of quiescent periods. See SI Text for details.

Protease Activity of BoNT/A and BoNT/E Holotoxins.

Recombinant SNAP-25 (46, 47) was incubated with 60 ng of BoNT holotoxin in 13.2 mM Hepes (pH 7.4), 20 mM DTT, and 1 μM Zn(CH3COOH)2 for 30 min at 37°C. SDS/PAGE (12%) was used to visualize cleavage of SNAP-25 by BoNT/A and BoNT/E holotoxins (48).

Fab Generation.

See SI Text for details.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank M. Goodnough for his invaluable help; J. Marks and M. C. Gonzalez (University of California, San Francisco) for antibodies; J. Santos, M. Oblatt-Montal, L. Koriazova, and members of the M.M. lab for perceptive comments; and R. Hampton, S. Emr, D. Fischer, and J. Young for helpful suggestions. This work was supported by U.S. Army Medical Research and Materiel Command Grant DAMD17-02-C-0106 and National Institutes of Health Training Grant T32 GM08326.

Abbreviations

- γ

single channel conductance

- BoNT

botulinum neurotoxin

- LC

light chain

- HC

heavy chain

- Po

channel open probability

- TCEP

tris-(2-carboxyethyl) phosphine

- V½

the voltage at which Po = 0.5

- SNARE

soluble NSF attachment protein receptor.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/cgi/content/full/0700046104/DC1.

References

- 1.Shapiro RL, Hatheway C, Swerdlow DL. Ann Intern Med. 1998;129:221–228. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-129-3-199808010-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arnon SS, Schechter R, Inglesby TV, Henderson DA, Bartlett JG, Ascher MS, Eitzen E, Fine AD, Hauer J, Layton M, et al. J Am Med Assoc. 2001;285:1059–1070. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.8.1059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Weber T, Zemelman BV, McNew JA, Westermann B, Gmachl M, Parlati F, Söllner TH, Rothman JE. Cell. 1998;92:759–772. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81404-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sutton RB, Fasshauer D, Jahn R, Brunger AT. Nature. 1998;395:347–353. doi: 10.1038/26412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jahn R, Lang T, Sudhof TC. Cell. 2003;112:519–533. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00112-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schiavo G, Matteoli M, Montecucco C. Physiol Rev. 2000;80:717–766. doi: 10.1152/physrev.2000.80.2.717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schiavo G, Benfenati F, Poulain B, Rossetto O, Polverino de Laureto P, DasGupta BR, Montecucco C. Nature. 1992;359:832–835. doi: 10.1038/359832a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Blasi J, Chapman ER, Link E, Binz T, Yamasaki S, De Camilli P, Sudhof TC, Niemann H, Jahn R. Nature. 1993;365:160–163. doi: 10.1038/365160a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jackson MB, Chapman ER. Annu Rev Biophys Biomol Struct. 2006;35:135–160. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biophys.35.040405.101958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lacy DB, Tepp W, Cohen AC, DasGupta BR, Stevens RC. Nat Struct Biol. 1998;5:898–902. doi: 10.1038/2338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lacy DB, Stevens RC. J Mol Biol. 1999;291:1091–1104. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1999.2945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Swaminathan S, Eswaramoorthy S. Nat Struct Biol. 2000;7:693–699. doi: 10.1038/78005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Simpson LL. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2004;44:167–193. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.44.101802.121554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Simpson LL. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1983;225:546–552. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dong M, Yeh F, Tepp WH, Dean C, Johnson EA, Janz R, Chapman ER. Science. 2006;312:592–596. doi: 10.1126/science.1123654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mahrhold S, Rummel A, Bigalke H, Davletov B, Binz T. FEBS Lett. 2006;580:2011–2014. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2006.02.074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rummel A, Karnath T, Henke T, Bigalke H, Binz T. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:30865–30870. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M403945200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nishiki T, Tokuyama Y, Kamata Y, Nemoto Y, Yoshida A, Sekiguchi M, Takahashi M, Kozaki S. Neurosci Lett. 1996;208:105–108. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(96)12557-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lawrence G, Wang J, Chion CK, Aoki KR, Dolly JO. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2007;320:410–418. doi: 10.1124/jpet.106.108829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Montecucco C, Schiavo G, Dasgupta BR. Biochem J. 1989;259:47–53. doi: 10.1042/bj2590047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Donovan JJ, Middlebrook JL. Biochemistry. 1986;25:2872–2876. doi: 10.1021/bi00358a020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Blaustein RO, Germann WJ, Finkelstein A, DasGupta BR. FEBS Lett. 1987;226:115–120. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(87)80562-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hoch DH, Romero-Mira M, Ehrlich BE, Finkelstein A, DasGupta BR, Simpson LL. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1985;82:1692–1696. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.6.1692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sheridan RE. Toxicon. 1998;36:703–717. doi: 10.1016/s0041-0101(97)00131-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Koriazova LK, Montal M. Nat Struct Biol. 2003;10:13–18. doi: 10.1038/nsb879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fischer A, Montal M. Neurotox Res. 2006;9:93–100. doi: 10.1007/BF03033926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sathyamoorthy V, DasGupta BR. J Biol Chem. 1985;260:10461–10466. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schiavo G, Rossetto O, Catsicas S, Polverino de Laureto P, DasGupta BR, Benfenati F, Montecucco C. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:23784–23787. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cai S, Kukreja R, Shoesmith S, Chang TW, Singh BR. Protein J. 2006;25:455–462. doi: 10.1007/s10930-006-9028-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Krantz BA, Finkelstein A, Collier RJ. J Mol Biol. 2006;355:968–979. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2005.11.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Krantz BA, Trivedi AD, Cunningham K, Christensen KA, Collier RJ. J Mol Biol. 2004;344:739–756. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.09.067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhang S, Udho E, Wu Z, Collier RJ, Finkelstein A. Biophys J. 2004;87:3842–3849. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.104.050864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bade S, Rummel A, Reisinger C, Karnath T, Ahnert-Hilger G, Bigalke H, Binz T. J Neurochem. 2004;91:1461–1472. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2004.02844.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schmid MF, Robinson JP, DasGupta BR. Nature. 1993;364:827–830. doi: 10.1038/364827a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gambale F, Montal M. Biophys J. 1988;53:771–783. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(88)83157-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Borochov-Neori H, Yavin E, Montal M. Biophys J. 1984;45:83–85. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(84)84117-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mitra K, Schaffitzel C, Shaikh T, Tama F, Jenni S, Brooks CL, III, Ban N, Frank J. Nature. 2005;438:318–324. doi: 10.1038/nature04133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Van den Berg B, Clemons WM, Jr, Collinson I, Modis Y, Hartmann E, Harrison SC, Rapoport TA. Nature. 2004;427:36–44. doi: 10.1038/nature02218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mokranjac D, Neupert W. Biochem Soc Trans. 2005;33:1019–1023. doi: 10.1042/BST20051019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rehling P, Brandner K, Pfanner N. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2004;5:519–530. doi: 10.1038/nrm1426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Schnell DJ, Hebert DN. Cell. 2003;112:491–505. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00110-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Truscott KN, Kovermann P, Geissler A, Merlin A, Meijer M, Driessen AJ, Rassow J, Pfanner N, Wagner R. Nat Struct Biol. 2001;8:1074–1082. doi: 10.1038/nsb726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hinnah SC, Wagner R, Sveshnikova N, Harrer R, Soll J. Biophys J. 2002;83:899–911. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(02)75216-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Heins L, Mehrle A, Hemmler R, Wagner R, Kuchler M, Hormann F, Sveshnikov D, Soll J. EMBO J. 2002;21:2616–2625. doi: 10.1093/emboj/21.11.2616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Movileanu L, Schmittschmitt JP, Scholtz JM, Bayley H. Biophys J. 2005;89:1030–1045. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.104.057406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Blanes-Mira C, Ibanez C, Fernandez-Ballester G, Planells-Cases R, Perez-Paya E, Ferrer-Montiel A. Biochemistry. 2001;40:2234–2242. doi: 10.1021/bi001919y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Oyler GA, Higgins GA, Hart RA, Battenberg E, Billingsley M, Bloom FE, Wilson MC. J Cell Biol. 1989;109:3039–3052. doi: 10.1083/jcb.109.6.3039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ferrer-Montiel AV, Canaves JM, DasGupta BR, Wilson MC, Montal M. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:18322–18325. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.31.18322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.