Abstract

Background

Jellyfish stings are a common occurrence among ocean goers worldwide with an estimated 150 million envenomations annually. Fatalities and hospitalizations occur annually, particularly in the Indo-Pacific regions. A new topical jellyfish sting inhibitor based on the mucous coating of the clown fish prevents 85% of jellyfish stings in laboratory settings. The field effectiveness is unknown. The objective is to evaluate the field efficacy of the jellyfish sting inhibitor, Safe Sea™.

Methods

A double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial occurred at the Dry Tortugas National Park, FL, USA and Sapodilla Cayes, Belize. Participants were healthy volunteers planning to snorkel for 30 to 45 minutes. Ten minutes prior to swimming, each participant was directly observed applying a blinded sample of Safe Sea (Nidaria Technology Ltd, Jordan Valley, Israel) to one side of their body and a blinded sample of Coppertone® (Schering-Plough, Kenilworth, NJ, USA) to the contralateral side as placebo control. Masked 26 g samples of both Safe Sea SPF15 and Coppertone® SPF15 were provided in identical containers to achieve 2 mg/cm2 coverage. Sides were randomly chosen by participants. The incidence of jellyfish stings was the main outcome measure. This was assessed by participant interview and examination as subjects exited the water.

Results

A total of 82 observed water exposures occurred. Thirteen jellyfish stings occurred during the study period for a 16% incidence. Eleven jellyfish stings occurred with placebo, two with the sting inhibitor, resulting in a relative risk reduction of 82% (95% confidence interval: 21%–96%; p = 0.02). No seabather’s eruption or side effects occurred.

Conclusions

Safe Sea is a topical barrier cream effective at preventing >80% jellyfish stings under real-world conditions.

An estimated 150 million people worldwide are exposed annually to jellyfish. In the United States, over 20% of the population report saltwater recreation annually. In 2002, 48 million Americans swam in salt water, 14.3 million snorkeled, and 4 million scuba dived one or more times.1 In the United States, 500,000 jellyfish stings are estimated to occur in the Chesapeake Bay and up to 200,000 stings in Florida waters annually.2 Episodic outbreaks result in mass envenomations and beach closures, as occurred in July 1997 at Waikiki Beach in Hawaii, when more than 800 persons were stung over 2 days.3 Marine envenomations occur worldwide, and at least 67 deaths have been attributed to the box jellyfish alone in the Indo-Pacific region.4,5 Australia in 2004 reported 19,277 marine stings with an average of 50 hospitalizations annually as a result of severe envenomations.6 Specifically, in Broome, Western Australia, rates of Irukandji syndrome, a severe jellyfish envenomation, were 3.3 per 1,000 among the general population from 2001 to 2003.7 In the Florida Keys, three cases of severe envenomation with Irukandji syndrome occurred in 2003.8 In 2004, a Thai child developed acute renal failure after a jellyfish sting.9

Methods to reduce jellyfish envenomations have traditionally relied on mechanical barriers. One common barrier method among surfer and divers includes personal wet suits/stinger suits. However, these suits often leave the face, hands, and feet exposed and are not commonly used by snorkelers or swimmers. A second method is surrounding swimming areas with netting to exclude jellyfish. This is common practice at many Australian and Pacific island beaches. While these nets may exclude the large box jellyfish (Chironex fleckeri) with a bell diameter of 20 to 30 cm, the nets’ 2.5 cm holes allow smaller stinging Irukandji jellyfish to enter. In Queensland, Australia, 60% of victims with Irukandji syndrome are stung within the confines of stinger nets.10

Safe Sea™ is a new, unique jellyfish sting inhibitor based on the chemical properties of the mucous coating of clownfish (genus: Amphiprion). Clownfish inhabit within the tentacles of sea anemones, which have stinging cells similar to those of jellyfish, yet clownfish are not stung by the sea anemones. In controlled laboratory environments, the jellyfish sting inhibitor, SafeSea, when applied to volunteers’ arms, prevented 100% of Chrysaora fuscescens stings and 70% of Chiropsalmus quadrumanus stings.11 Of the C. quadrumanus stings that occurred, their intensity was diminished.11 The mechanism of Safe Sea’s sting prevention is multifactorial (Table 1).

Table 1.

Mechanism of sting inhibition by Safe Sea

|

Safe Sea is the first commercially available product utilizing this approach to sting inhibition and is marketed as a “jellyfish safe sun block” (Nidaria Technology Ltd, Jordan Valley, Israel). Safe Sea is effective in clinical human laboratory trials but has not been field tested.11 This is the first field trial of this new jellyfish sting inhibitor testing its efficacy.

Methods

A prospective, double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial occurred investigating the prevention of jellyfish stings. Participants intending to snorkel were given blinded 26 g samples of both Safe Sea SPF15 (Nidaria Technology) and Coppertone ®SPF15(Schering-Plough, Kenilworth, NJ, USA). The lotions’ color and aroma were indistinguishable. Each lotion was provided in identical 30 mL containers colored purple or pink. Assuming an average body surface area of 2.5 m2, 52 g of sun-screen complied with the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and the European Cosmetic Toiletry and Perfumery Association (COLPA) guidelines for 2 mg/cm2 of sunscreen application.12,13 Each container was to be used completely per application.

Participants applied each lotion to opposite sides of their body 10 minutes prior to swimming. One side (right or left) had Safe Sea, while the opposite had Coppertone applied. The Coppertone side of the body served as a matched placebo control. Sides were randomly chosen by participants. The principal investigator (PI) observed application and recorded to which side of the body each lotion was applied (Figure 1). The products dried prior to water entry. For each water exposure, participants had matched sides of sting inhibitor and control. Participants swam for up to 45 minutes, with the duration recorded. Upon exiting the water, participants were immediately interviewed by the PI as to whether any stings occurred. Stings were self-reported but examined by the PI. Within 15 minutes of leaving the water, participants showered with fresh water. If individuals re-entered the water, the application protocol was repeated. Follow-up physical examination occurred daily during the study period. Participant’s body hair was quantified on a zero (none), one (light), to two (heavy) scale. Digital photography documented any dermatitis.

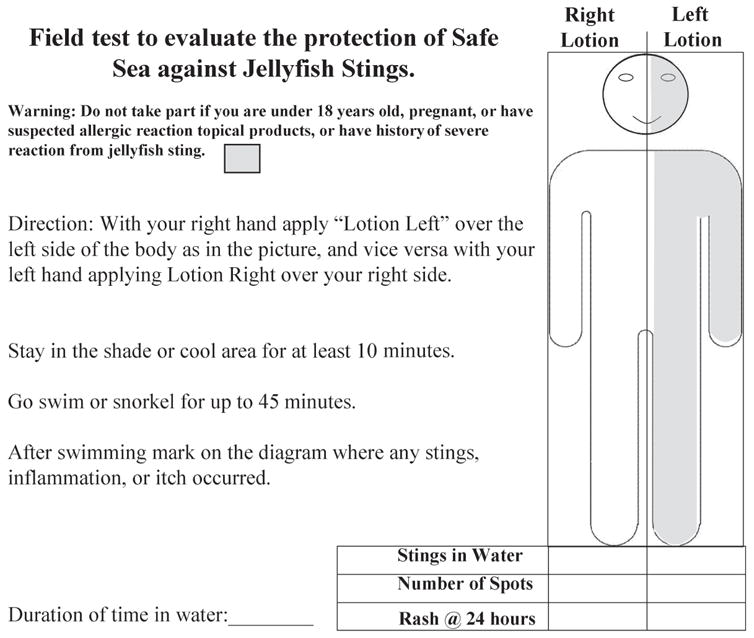

Figure 1.

Survey form.

Participants and Setting

This study occurred in the Dry Tortugas National Park (NP), 110 km (68 miles) west of Key West, Florida on April 25 to 30, 2004 and in the Sapodilla Cayes, Belize on January 25 to 30, 2005. In the Dry Tortugas NP, the water temperature was 23°C (73°F).14 In Belize, the water temperature was 27°C (80.5°F). Both sites were chosen due to their popularity with snorkelers and divers and propensity for jellyfish during the study periods. Six participants were recruited through direct solicitation for volunteering for each 6-day study period. Two persons volunteered twice (10 total individuals). The exclusion criteria were age <18 years, pregnancy, severe allergy to jellyfish, and allergy to any topical dermatologic product. Institutional Review Board (IRB) approval and written consents were obtained. The ClinicalTrials.gov number is NCT00114894.

Sample Size

We selected our sample size by calculating a power of 80% for a significance level of 0.05 with a 75% protection rate for those receiving the sting inhibitor and a 16% sting rate for the placebo group. The sample size was calculated as 72 paired observations. The baseline sting rate of 16% was chosen on the basis of the incidence rate of seabather’s eruption, caused by the thimble jellyfish, in a previous prospective South Florida cohort.15 The study was powered conservatively for a 75% relative risk reduction of jellyfish stings on the basis of the published 85% laboratory protection rate.11

Randomization

Randomization of the sides of the body for lotion application was determined by each participant, and their choice recorded by a masked observer. A priori calculations were designed prior to study initiation for automatic data analysis in case of accidental unmasking during the protocol.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical calculations were performed via SPSS 13.0 (Chicago, IL). Comparisons are expressed as relative risk (RR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI). Differences between proportions were analyzed by using the two-tailed McNemar’s test to compare the paired, nominal data of the occurrence of jellyfish stings. The relationship between body hair density and jellyfish stings was compared with the Kruskal Wallis test. The primary outcome measure is the incidence of jellyfish stings. No secondary analyses occurred.

Results

Ten individuals, seven men and three women, participated in a total of 82 paired water exposures. Participants’ average (±SD) age was 29 ± 2 years, weight 74 ± 15 kg, and body surface area 1.9 ± 0.2 m2. Eight participants previously had experienced jellyfish stings, and four had experienced seabather’s eruption. Complete follow-up occurred for every person for every exposure. The median duration in the water was 30 minutes (range 25–45 minutes).

Thirteen jellyfish stings were self-reported during the study period with 1.6 ± 3.7 stings per 10 water exposures (Table 2). Two jellyfish stings occurred with the sting inhibitor: 0.2 ± 1.5 stings/10 exposures (0.2 ± 0.4 stings/person) compared to 11 with placebo: 1.3 ± 3.4 stings/10 exposures (1.1 ± 1.3 stings/person). The sting inhibitor reduced jellyfish stings by 82% (RR: 0.18; 95% CI: 0.04–0.79; P = 0.02). One severe envenomation occurred among the placebo resulting in erythema (6 cm diameter on the wrist) and dysesthesias lasting 14 days.

Table 2.

Jellyfish sting data

| Sex | Exposures | Safe Sea stings | Placebo stings | Hair density |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | 14 | 1 | 4 | 2 |

| F | 7 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| M | 13 | 1 | 2 | 2 |

| M | 8 | 0 | 1 | 2 |

| F | 7 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| F | 6 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| M | 6 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| M | 7 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| M | 7 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| M | 7 | 0 | 2 | 1 |

| Total | 82 | 2 | 11 | |

| Mean/exposure | 10 | 0.2 | 1.3 | |

| p value | 0.022 | 0.15 |

The number needed to treat (NNT) in this study is nine (95% CI: 5 to 35) to prevent one envenomation. Those with greater amounts of body hair trended toward increased jellyfish stings (RR: 3.1; 95% CI: 0.9–17.9; χ = 4.2, 2 df, P = 0.15). All stings occurred on extremities in open water.

Cercarial dermatitis (swimmer’s itch) occurred among six individuals in Belize. No seabather’s eruption or other adverse skin reactions were reported. Levels of sun tanning did not differ between contralateral sides. Masking was successful through data analysis. After data analysis, inquiry with study participants revealed continued uncertainty as to which lotion was the active treatment, with 40% believing the placebo was the active treatment.

Discussion

The jellyfish sting inhibitor, Safe Sea, had an >80% reduction in jellyfish stings under real-world conditions during a field trial. The sting inhibitor is designed to keep jellyfish nematocysts (stingers) from being activated and is based on the chemical properties of the mucous coating of clownfish. Clownfish inhabit sea anemones, which have similar stinging nematocysts as jellyfish, yet clownfish mucous prevents stings by sea anemones. 16 The nematocysts require stimulation by both chemical and tactile stimuli to fire.17–19 Evolutionarily, this makes sense for jellyfish or sea anemones not to needlessly discharge their nematocysts against inanimate objects or themselves.

Safe Sea prevents nematocysts from firing; however, once the stingers have fired, Safe Sea is ineffective in blocking or neutralizing the sting itself. The inhibitor is composed not of one single chemical but an amalgamation. The principal of sting prevention is fourfold. First, the inhibitor is highly hydrophobic, convenient for waterproofing, yet this decreases tentacle contact with the skin, increasing the difficulty of envenomation.11,19 Second, the inhibitor contains glycosaminoglycans that mimic the glycosaminoglycans comprising the jellyfish’s bell (ie, body). Because this bell is part of the jelly’s self-recognition system (thereby preventing it from stinging itself), the inhibitor mimics this self-recognition system to interfere with nematocysts firing. Third, the inhibitor contains a competitive antagonist to nonselective chemoreceptors on jellyfish. These receptors normally bind amino acids and sugar secretions from prey, sensitizing the nematocysts to enable firing thereafter upon mechanical or vibratory stimuli.18,20,21 Finally, calcium and magnesium block transmembrane signaling and reduce the osmotic force within the nematocyst capsule necessary to create the firing force.21

As a field trial, this study was operational and attempted to evaluate the sting inhibitor under real-world conditions. The activities and duration of snorkeling were spontaneous. The IRB deemed it unethical to purposely elicit jellyfish stings. Neither restriction nor solicitation of an activity occurred while snorkeling. Thus, this trial should be generalizable to the general population.

Regarding swimmer’s itch, six individuals had an erythematous, papular, highly pruritic rash on exposed skin with complete sparing under swimwear. The rash’s distribution was symmetric involving both sides equally. Cercarial dermatitis is caused by nonhuman infecting schistosoma larvae burrowing into the epidermis, and Safe Sea would not be expected to prevent swimmer’s itch.

The NNT of nine was indicative of the concentration of jellyfish in this study. Local, seasonal, and climate factors vary the number and danger of jellyfish to ocean goers. Where jellyfish are reported by public health authorities or are particularly dangerous, sting inhibitors would be warranted.

Limitations

The ocean exposures in this study were <45 minutes. We did not attempt to determine the effective duration of protection after a single application. Importantly, Safe Sea may have variability in protection against different jellyfish species, as both clownfish and predators of Cnidaria typically possess species specificity for their protection.22

Future Areas of Study

This study was conducted in the Gulf of Mexico and Caribbean where C. quinquecirrha (sea nettle), C. quadrumanus (sea wasp), Lunuche ungulate (thimble), and Physalia spp (Portuguese-man-of-war) predominate.19 In this study, no Portuguese man-of-war were identified by participants. Protection against more venomous jellyfish such as the Indo-Pacific box jellyfish, Irukandji jellyfish, and Portuguese man-of-war would be of great interest. As the sting from a box jellyfish carries a mortality rate of 15%,23 animal studies would first be advisable to prove laboratory efficacy. A randomized, controlled trial during a high incidence season in a high sting area such as Cairns, Queensland in December or Broome, Western Australia in January would be desirable.7,10 This study demonstrates comparable real-world efficacy in the setting of a field trial to experimental laboratory models.

Conclusions

Safe Sea, a topical jellyfish sting inhibitor, is effective at preventing jellyfish stings in the setting of a field trial in the Gulf of Mexico and Caribbean. The field efficacy of the sting inhibitor was similar to the prior laboratory established efficacy; thus, laboratory studies should be comparable to expected real-world results in the future.

Cercarial dermatitis, commonly known as swimmer’s itch, is caused by non-human Schistosoma specie larvae burrowing into the epidermis. An erythematous, papular eruption occurred 12 hours after snorkeling. The pruritic rash was present on the trunk and exposed skin with complete sparing under swimwear covered areas. Swimmer’s itch may occur either in salt or fresh water. The area of distribution of the dermatitis is in contrast to Seabather’s Eruption caused by envenomation by the larvae of thimble jellyfish which occurs under swimwear covered areas only in salt water. Submitted by Greta B. Chen MD

Acknowledgments

Appreciation is extended to the study volunteers, Amit Lotan, PhD, for provision of the blinded samples, and Drs. Paul Auerbach, Bill Stauffer, Edward Janoff, and Paul Shaffer for critical manuscript review. Research support is appreciated from Drs. Kimberly Bohjanen and Bradley Benson. Nidaria Technology provided the blinded samples but had no role in the design, conduct, or analysis of the study.

Footnotes

The abstract was presented at the 9th CISTM on May 1 to 5, 2005 in Lisbon, Portugal.

References

- 1.1999–2002 National Survey on Recreation and the Environment, USDA Forest Service and the University of Tennessee, Knoxville, Tennessee. Available at: http://www.srs.fs.usda.gov/trends/Nsre/Rnd1t13unweightrpt.pdf. (Accessed 2005 Feb 7)

- 2.Burnett JW. Human injuries following jellyfish stings. Md Med J. 1992;41:509–513. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Thomas CS, Scott SA, Galanis DJ, Goto RS. Box jellyfish (Carybdea alata) in Waikiki: their influx cycle plus the analgesic effect of hot and cold packs on their stings to swimmers at the beach: a randomized, placebo-controlled, clinical trial. Hawaii Med J. 2001;60:100–107. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fenner PJ, Hadok JC. Fatal envenomation by jellyfish causing Irukandji syndrome. Med J Aust. 2002;177:362–363. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2002.tb04838.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nimorakiotakis B, Winkel KD. Marine envenomations: part One—Jellyfish. Aust Fam Physician. 2002;31:969–974. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Surf Life Saving Australia. Bondi Beach; NSW, Australia: [Accessed 2005 Feb 7]. Annual Report 2003–2004. Available at: http://www.slsa.asn.au/doc_display.asp?document_id=73. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Macrokanis CJ, Hall NL, Mein JK. Irukandji syndrome in northern Western Australia an emerging health problem. Med J Aust. 2004;181:699–702. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2004.tb06527.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Grady JD, Burnett JW. Irukandji-like syndrome in South Florida divers. Ann Emerg Med. 2003;42:763–766. doi: 10.1016/s0196-0644(03)00513-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Deekajorndech T, Kingwatanakul P, Wananukul S. Acute renal failure in a child with jellyfish contact dermatitis. J Med Assoc Thai. 2004;87:S292–294. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Little M, Mulcahy RF. A year’s experience of Irukandji envenomation in far north Queensland. [Accessed 2005 Feb 7];Med J Aust. 1998 169:638–641. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.1998.tb123443.x. Available at: http://www.mja.com.au/public/issues/xmas98/little/little.html. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.Kimball AB, Arambula KZ, Stauffer AR, et al. Efficacy of a jellyfish sting inhibitor in preventing jellyfish stings in normal volunteers. Wilderness Environ Med. 2004;15:102–108. doi: 10.1580/1080-6032(2004)015[0102:eoajsi]2.0.co;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Food and Drug Administration. Sunscreen drug products for over-the-counter human use; Final monograph. [Accessed 2004 Apr 20];Fed Regist. 1999 64:27691. Available at: http://www.fda.gov/OHRMS/DOCKETS/98fr/052199b.txt. [PubMed]

- 13.Sayre RM, Stanfield J, Lott DL, Dowdy JC. Simplified method to substantiate SPF labeling for sun-screen products. Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed. 2003;19:254–260. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0781.2003.00050.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.NOAA Weather Buoy Data. [Accessed 2004 Apr 23 and 2005 Feb 7]; Available at: http://www.ndbc.noaa.gov/station_page.phtml?station=DRYF1.

- 15.Kumar S, Hlady WG, Malecki JM. Risk factors for seabather’s eruption: a prospective cohort study. Public Health Rep. 1997;112:59–62. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mebs D. Anemonefish symbiosis: vulnerability and resistance of fish to the toxin of the sea anemone. Toxicon. 1994;32:1059–1068. doi: 10.1016/0041-0101(94)90390-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pantin CF. Excitation of nematocyst. Nature. 1942;149:109. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Watson GM, Roberts J. Chemoreceptor-mediated polymerization and depolymerization of actin in hair bundles of sea anemones. Cell Motil Cytoskeleton. 1995;30:208–220. doi: 10.1002/cm.970300305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fenner PJ. University of London: [Accessed 2005 Feb 7]. The global problem of cnidarian (jellyfish) stinging. Available at: http://www.marine-medic.com.au/pages/thesis.html. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Watson GM, Hessinger DA. Evidence for calcium channels involved in regulating nematocyst discharge. Comp Biochem Physiol Comp Physiol. 1994;107:473–481. doi: 10.1016/0300-9629(94)90028-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ozacmak VH, Thorington GU, Fletcher WH, Hessinger DA. N-acetylneuraminic acid (NANA) stimulates in situ cyclic AMP production in tentacles of sea anemone (Aiptasia pallida): possible role in chemosensitization of nematocyst discharge. J Exp Biol. 2001;204:2011–2020. doi: 10.1242/jeb.204.11.2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Greenwood PG, Garry K, Hunter A, Jennings M. Adaptable defense: a nudibranch mucus inhibits nematocyst discharge and changes with prey type. Biol Bull. 2004;206:113–120. doi: 10.2307/1543542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Auerbach PA. Envenomations by Aquatic Invertebrate. In: Auerbach PA, editor. Wilderness medicine. 4. St. Louis, MO: Mosby; 2001. pp. 1488–1506. [Google Scholar]