Abstract

The ubiquitin-like hPLIC proteins can associate with proteasomes, and hPLIC overexpression can specifically interfere with ubiquitin-mediated proteolysis (Kleijnen et al., 2000). Because the hPLIC proteins can also interact with certain E3 ubiquitin protein ligases, they may provide a link between the ubiquitination and proteasomal degradation machineries. The amino-terminal ubiquitin-like (ubl) domain is a proteasome-binding domain. Herein, we report that there is a second proteasome-binding domain in hPLIC-2: the carboxyl-terminal ubiquitin-associated (uba) domain. Coimmunoprecipitation experiments of wild-type and mutant hPLIC proteins revealed that the ubl and uba domains each contribute independently to hPLIC-2–proteasome binding. There is specificity for the interaction of the hPLIC-2 uba domain with proteasomes, because uba domains from several other proteins failed to bind proteasomes. Furthermore, the binding of uba domains to polyubiquitinated proteins does not seem to be sufficient for the proteasome binding. Finally, the uba domain is necessary for the ability of full-length hPLIC-2 to interfere with the ubiquitin-mediated proteolysis of p53. The PLIC uba domain has been reported to bind and affect the functions of proteins such as GABAA receptor and presenilins. It is possible that the function of these proteins may be regulated or mediated through proteasomal degradation pathways.

INTRODUCTION

The two hPLIC proteins, the human homologs of Saccharomyces cerevisiae Dsk2, are UDP (ubiquitin-domain) proteins, which are characterized by having a noncleavable ubiquitin-like domain as part of their open reading frame (Hochstrasser, 2000; Jentsch and Pyrowolakis, 2000). In addition to the ubiquitin-like domain in the amino terminus, the hPLIC proteins have a ubiquitin-associated (uba) domain in the extreme carboxy terminus. The ubiquitin-like domains of UDP proteins turn out to be proteasome-binding domains (Schauber et al., 1998; Hiyama et al., 1999; Kleijnen et al., 2000; Luders et al., 2000; Elsasser et al., 2002). From a nuclear magnetic resonance solution structural analysis of the hPLIC-2 ubl domain, we have recently reported that the ubiquitin surface involved in polyubiquitin chain binding to the proteasome is conserved in the ubl domains of UDP proteins and is also required for binding of the ubl domain to the proteasome (Walters et al., 2002). It is as of yet unclear what role hPLIC binding to the proteasome may have regarding the targeting of substrates via their polyubiquitin chain tag to the proteasome.

In eukaryotic cells, the ubiquitination machinery and the proteasome have coevolved to execute controlled proteolysis. The ubiquitination machinery consists of an enzymatic cascade, designed to posttranslationally attach ubiquitin polypeptides onto lysine residue side chains in a substrate via isopeptide bonds. The attachment process is initiated by a ubiquitin-activating enzyme, E1, which activates ubiquitin by forming a thiolester bond between the carboxy terminus of ubiquitin and the thiol group of a specific cysteine residue of E1. The ubiquitin moiety is transferred to a ubiquitin-conjugating (ubc) enzyme, E2, which functions with a ubiquitin protein ligase E3 enzyme to transfer ubiquitin onto a substrate. The E3 enzymes catalyze the formation of an isopeptide bond between the carboxy terminus of ubiquitin and the ε-amino group of a lysine residue on the target protein. Polyubiquitin chains result from attaching additional ubiquitin moieties to internal lysines of the previously attached ubiquitin polypeptide (reviewed in Ciechanover, 1998; Hershko and Ciechanover, 1998; Pickart, 2001). An attached polyubiquitin chain makes a protein a target for proteasomal degradation. The proteasome particle consists of a 20S core particle that can bind 19S/PA700 cap complexes to generate the complete 26S proteasome (reviewed in Coux et al., 1996; Baumeister et al., 1998; Voges et al., 1999). Access to the catalytic activity, which resides in the 20S core particle, is thought to be controlled by the cap complexes that have the ability to bind polyubiquitin chains attached to degradation substrates. The precise nature of the polyubiquitin chain receptor in the proteasomal cap is still unclear.

Even though a polyubiquitin chain has the capacity to target a substrate to the proteasome via the polyubiquitin chain receptor and to mediate its degradation in vitro, there is recent data in the literature to suggest that this mode may not always reflect protein degradation under in vivo circumstances. Rather, substrate ubiquitination and degradation in vivo may be facilitated by the physical association of ubiquitination machinery components with the proteasome. Associations of components of the ubiquitination machinery with the proteasome have been previously reported (Kleijnen et al., 2000; Tongaonkar et al., 2000; Verma et al., 2000; Xie and Varshavsky, 2000, 2002; Leggett et al., 2002). Our work on the ubiquitin-like hPLIC proteins suggests that these physical interactions may be relevant for in vivo substrate degradation. The hPLIC proteins associate with both proteasomes and specific ubiquitin ligases. Overexpression of hPLIC proteins interferes with the in vivo degradation of two unrelated ubiquitin-dependent proteasome substrates, p53 and IκBα, but not with the degradation of a ubiquitin-independent substrate. These findings raise the possibility that the hPLIC proteins may provide a functional link between the ubiquitination machinery and the proteasome to affect in vivo protein degradation (Kleijnen et al., 2000).

The ubiquitin-associated (uba) domain is a small loosely defined motif present in many proteins involved in ubiquitination and protein degradation, but its role is still unclear (Hofmann and Bucher, 1996). The structure of one of the two uba domains present in hHR23A has been solved and consists of a tight three-helix arrangement, with conserved residues involved in keeping the helices together in a tight knot (Dieckmann et al., 1998; Mueller and Feigon, 2002). A number of recent articles report that uba domains can interact with ubiquitin and multi-ubiquitin chains (Vadlamudi et al., 1996; Bertolaet et al., 2001b; Chen et al., 2001; Wilkinson et al., 2001; Chen and Madura, 2002; Funakoshi et al., 2002; Rao and Sastry, 2002), and this may represent a general function for the uba domain. Herein, we report that the uba domain in the extreme carboxy terminus of hPLIC-2 interacts with the proteasome. Both the ubl domain and the uba domain in hPLIC-2 are proteasome interaction domains, and each partially contributes to the overall binding of hPLIC-2 to the proteasome. Like the ubl domain, the uba domain is by itself capable of pulling down proteasomes from cell lysates. Even though the hPLIC-2 uba domain can bind polyubiquitin chains like other uba domains, this ability does not correlate with proteasome binding, arguing that an interaction with polyubiquitin chains is not sufficient to mediate the binding of a uba domain and the proteasome. Furthermore, the hPLIC-2 uba domain can interact directly with purified yeast proteasomes. The hPLIC-2 uba domain can bind to in vitro synthesized S5a proteasomal cap subunit, suggesting that this may be its proteasomal binding site. In addition, the uba domain is required for interference with p53 degradation upon hPLIC-2 overexpression, suggesting that the uba–proteasome interaction may be functionally relevant. Importantly, the proteasome-binding ability of the hPLIC-2 uba domain is a property that is not a general among all uba domains, in that proteasome binding was not found for several other uba domains tested.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plasmid Constructs

The pCMV4 eukaryotic expression vector containing N-terminally FLAG-tagged full-length wild-type hPLIC-2 has been described previously (Kleijnen et al., 2000) (plasmid p4455). This construct was used to generate a vector expressing FLAG-tagged full-length hPLIC-2 with a triple mutation in the ubl domain (I75A, A77S, H99A) (plasmid p4609), a vector expressing FLAG-tagged hPLIC-2 with a wild-type ubl but lacking the extreme carboxy-terminal uba domain (plasmid p4592, aa 1–577) and a vector expressing FLAG-tagged hPLIC-2 containing the triple mutation in the ubl domain and that also lacks the uba domain (plasmid p4610, aa 1–577). The glutathione S-transferase (GST) fusion constructs shown in Figures 2 and 3 were all made by cloning different hPLIC-2 fragments into the BamH1 and EcoR1 sites of the pGEX-2T vector (Amersham Biosciences, Piscataway, NJ). The hPLIC-2 fragments used are aa 26–103 (ubl domain) (plasmid 04602), aa 143–624 and aa 143–576 (plasmids p4603 and p4604), aa 339–624 and aa 339–576 (plasmids p4605 and p4606), aa 484–624 (plasmid p4607), and aa 574–624 (uba domain) (plasmid p4608). The constructs are mentioned herein in the order in which they were used in Figure 2. The GST-uba c-cbl construct in Figure 3, A and C, contains aa 849–907, which includes the uba domain preceded by 7 aa and followed by 12 aa (plasmid p4611). Also generated was a GST-uba c-cbl construct containing exactly the uba domain (aa 856–895) (plasmid p4612), which behaved identically. This construct was used in Figure 3D. A GST construct with the human isopeptidase T uba domain (aa 645–684) was also generated (plasmid p4613) and used in Figure 3B.

Figure 2.

The hPLIC-2 uba domain can bind proteasomes in a GST pull-down experiment. (A) List of GST-hPLIC-2 fusion constructs. (B) GST alone (lane 1) and the indicated GST-hPLIC-2 fusion proteins (lanes 2–8) were bacterially expressed, purified, bound to glutathione-Sepharose beads, and analyzed by Coomassie staining (M, marker lane). (C) The beads were incubated with HeLa cell lysate, pulled down, and assayed for proteasome binding by blotting for the α2 proteasomal core subunit.

Figure 3.

Specificity of the hPLIC-2 uba domain–proteasome interaction. (A) The hPLIC-2 uba domain but not the c-cbl uba domain can interact with proteasomes. GST fusions of the uba domains of hPLIC-2 (lane 2) and c-cbl (lane 3) were compared for their ability to pull down proteasomes. GST fusions were mixed with HeLa cell lysate, and proteasome proteins were analyzed by Western blotting for the α2 proteasomal core subunit. (B) Uba domain binding to polyubiquitin chains does not correlate with proteasome pull down. The indicated GST fusion proteins were tested for their ability to pull down polyubiquitinated proteins from HeLa cell lysate, in the same experimental setup as described above. The ability of these GST constructs to pull down proteasomes was tested in a separate experiment (bottom). (C) The ubl and uba domains of hPLIC-2 fused to GST can bind purified yeast proteasomes, whereas the uba domain of c-cbl cannot. Proteasome components precipitating with the GST-fusion proteins were detected by Western blotting for the Rpt2 proteasomal cap subunit. (D) Both the ubl and uba domains of hPLIC-2 can bind to in vitro synthesized proteasomal cap subunit S5a. In vitro translated 35S-labeled S5a was mixed with the indicated GST fusion proteins, pulled down, analyzed by SDS-PAGE, and exposed to film.

Transient Transfection Conditions

HeLa cells were transiently transfected to high-efficiency (>70%) by using FuGENE (Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN). Sixteen microliters of FuGENE in 180 μl of serum-free DMEM was added to 9 μg of expression vector DNA in 20 μl of H2O. This inoculum was added to 4 ml of medium on a subconfluent 10-cm dish and incubated for 40 h, at which time the cells were harvested.

Immunoprecipitation

Before cell lysis, proteasome inhibitor ZL3VS (Bogyo et al., 1998) was added to the culture medium at a final concentration of 50 μM for 2 h (Kleijnen et al., 2000). Cells were lysed in NP-40 lysis buffer (0.5% NP-40, 50 mM Tris-HCl pH 8.0, 5 mM MgCl2) containing 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride. Nuclei and insoluble debris were removed by centrifugation (Eppendorf 5415C centrifuge; 14,000 rpm, 10 min). Immunoprecipitations were performed with the anti-FLAG tag M2 antibody (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) and protein G agarose beads (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). The beads were washed three times in 1× NET buffer (0.5% NP-40, 150 mM NaCl, 50 mM Tris-HCl pH 8.0, 5 mM EDTA) and analyzed by SDS-PAGE and Western blotting for the α2 proteasomal core subunit C3 (α-p25, clone 7A11, ICN/Cappel, Durham, NC; see below) as well as the M2 antibody (Sigma-Aldrich). In Figure 5, total cell lysates from cells not treated with proteasome inhibitor were blotted with the α-p53 monoclonal antibody from Calbiochem (San Diego, CA) (antibody-6).

Figure 5.

The uba domain is required for interfering with the degradation of p53 in HeLa cells upon hPLIC-2 overexpression. (A) List of expression vectors used. (B) FLAG-tagged hPLIC-2, full-length or lacking the uba domain, either wild type or with the I75A/A77S/H99A triple mutation in the ubl domain, was transfected into HeLa cells. Total cell lysates were analyzed by Western blotting for p53 levels. hPLIC expression levels were checked with the FLAG antibody.

Proteasome Pull Down from Cell Lysate

The GST constructs were isopropyl β-d-thiogalactoside–induced (500 ml cultures, 0.5 mM isopropyl β-d-thiogalactoside at OD600 = 0.6, 30°C overnight), and the pellets were resuspended in 8 ml of phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). Lysates were generated by sonication and cleared by centrifugation (25 min, 10,000 rpm, SS34 rotor). Supernatant was incubated with 250 μl of PBS-washed glutathione-Sepharose beads (Invitrogen) for 1.5 h at 4°C to achieve high concentrations of the GST proteins on the beads. After washing in PBS, bound protein was analyzed by SDS-PAGE and Coomassie staining. HeLa cells were harvested in NP-40 lysis buffer (50 mM Tris, pH 8.0, 0.5% NP-40, 5 mM MgCl2), and lysates were cleared by centrifugation. 20 μl of glutathione-Sepharose beads loaded with protein was incubated with cell lysate for 1.5 h at 4°C. Lysate from half a 150-cm2 dish of subconfluent HeLa cells was used per pull down. The beads were washed in the same NP-40 lysis buffer, subjected to SDS-PAGE, and transferred to membrane for Western blotting by using the α2 proteasomal core subunit antibody α-p25 (clone 7A11; ICN/Cappel) or the α1 proteasomal core subunit antibody α-p27 (clone IB5; ICN/Cappel) (our unpublished data). The α-p25 antibody detects two bands in HeLa cell lysate. By comparing α-p25 with α-p27 and a third proteasomal core antibody against the α6 subunit, 62A32, we have previously shown that both bands are proteasome related and that these antibodies can detect proteasomal core antigens in Western blotting (Kleijnen et al., 2000; Walters et al., 2002). Most likely, the two α-p25 bands represent different splice variants that may depend on the particular cell line one uses, because a similar situation has been reported for the 62A32 antibody (Silva Pereira et al., 1992; Henry et al., 1997). It was discovered that the proteasomal core antigens could be preferentially eluted from the beads with a wash in NP-40 lysis buffer supplemented with 150 mM NaCl (the GST proteins remain on the beads), allowing for clean Western blotting. A polyclonal antibody against ubiquitin-protein conjugates was used in Figure 3B, the membrane being boiled before use (Affiniti UG 9510). In Figure 3C, affinity-purified yeast proteasomes were taken up in NP-40 lysis buffer, and the pull down was performed as described above. For detection, an α-yta5/rpt2 polyclonal antibody was used (Affiniti). Yeast proteasomes were purified to homogeneity (our unpublished data). The yeast proteasome purification procedure has been described previously (Leggett et al., 2002). In Figure 3D, His-tagged S5a (plasmid 04514) was in vitro translated and 35S-labeled (rabbit reticulocyte TNT-coupled reaction; Promega, Madison, WI). The pull down was performed in the above-mentioned NP40 lysis buffer. Quantification of band intensities was done using NIH Image.

RESULTS

By solution structural analysis, the surface on the hPLIC-2 ubl domain that binds to the S5a proteasome subunit has been defined (Walters et al., 2002). A triple mutation (I75A/A77S/H99A) in the binding surface of the ubl domain abolished the ability of the bacterially expressed hPLIC-2 ubl domain to pull down proteasomes from cell lysate, while not affecting overall ubl domain structure (Walters et al., 2002).

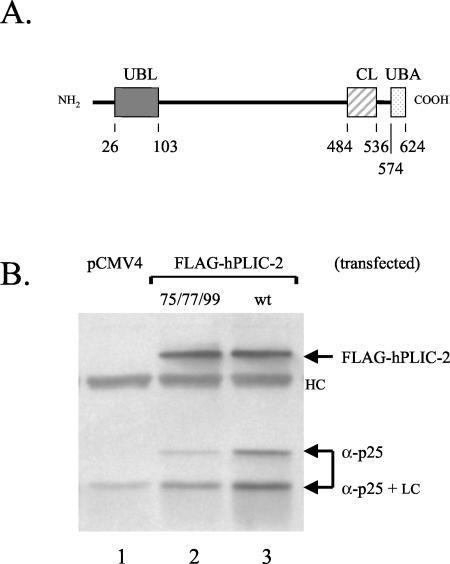

Interestingly however, this triple amino acid substitution mutation in the full-length hPLIC-2 protein only partially interfered with the ability of hPLIC-2 to bind the proteasome. Introduction of the I75A/A77S/H99A ubl triple mutation into full-length hPLIC-2 reduced by 71% the coimmunoprecipitation of proteasomes (Figure 1B, compare lanes 2 and 3), suggesting the possibility of additional proteasome binding site(s) in the full-length hPLIC-2 protein.

Figure 1.

The hPLIC-2 I75A/A77S/H99A triple mutation in the ubl domain retains binding to the proteasome. (A) Schematic representation of hPLIC-2 depicting the amino-terminal ubl domain (shaded), the collagen-like domain (CL) (hatched), and the carboxyl-terminal uba domain (dotted). (B) FLAG-tagged, full-length, wild-type hPLIC-2 (lane 3), full-length hPLIC-2 containing a I75A/A77S/H99A triple mutation in the ubl domain (lane 2), or vector alone (lane 1) was transfected into HeLa cells and treated with proteasome inhibitor before cell lysis. hPLIC-2 was immunoprecipitated and assayed by Western blotting with both a FLAG tag antibody and the α2 proteasomal core subunit antibody. LC and HC depict the IgG light chain and heavy chain, respectively.

To investigate the possibility of additional independent proteasome binding site(s) in hPLIC-2, a series of deletion mutants were constructed and assayed for their ability to bind the proteasome. GST fusion constructs containing different portions of hPLIC-2 were analyzed for their ability to pull down proteasomes from cell lysates. GST alone was not capable of binding proteasomes, whereas GST-ubl bound the proteasomes well (Figure 2, lanes 1 and 2) in agreement with our previous report (Walters et al., 2002). Interestingly, the uba domain at the C termini of hPLIC-2 also was capable of independently interacting with proteasomes in this assay (lane 8). Using the panel of GST-hPLIC-2 fusion constructs shown in Figure 2A, we found that the ubl-independent proteasome association mapped to the uba domain. Therefore, the ubl and uba domains of hPLIC-2 represent two independent proteasome interaction domains.

We next tested whether the binding of the uba domain to the proteasome was a general uba domain function or specific for the hPLIC-2 uba domain. The c-cbl uba domain was therefore assayed for proteasome binding. In a side-by-side experiment with the hPLIC-2 uba domain, we found that the c-cbl uba domain was not capable of pulling down proteasomes from cell lysate (Figure 3A). Also, the human isopeptidase T uba domain did not interact with proteasomes in a similar assay (Figure 3B). Therefore, the ability of the hPLIC-2 uba domain to associate with proteasomes is not a general property of all uba domains and may be specific for a certain subset of uba domains.

As mentioned in the introduction, polyubiquitin chain binding is most likely a general property of uba domains. To assess whether the uba domain of hPLIC-2 can bind polyubiquitin chains and whether such an ability correlates with proteasome binding, we analyzed different GST-uba constructs for their abilities to pull down polyubiquitinated proteins from a HeLa cell lysate and for their abilities to pull down proteasomes. As shown in Figure 3B, top, all three uba domains tested pulled down polyubiquitinated proteins from cell lysate and the GST control as well as the hPLIC-2 ubl domain cannot. In the experiment shown in Figure 3B, bottom, with a different lysate, the hPLIC-2 uba domain but not the c-cbl uba domain or the isopeptidase T uba domain could pull down proteasomes (also see Figure 3A). This indicates that the interaction of a uba domain with polyubiquitin chains is by itself not sufficient to mediate binding to the proteasome. This suggests that the hPLIC-2 uba domain–proteasome interaction could be direct involving a component of the proteasome other than associated polyubiquitinated proteins. Alternatively, the binding could be indirect mediated by polyubiquitinated chains associated with the proteasome. If the binding was mediated solely through binding to polyubiquitinated chains however, there would have to be some unique binding characteristic (such as increased affinity) of the hPLIC-2 uba domain to polyubiquitin chains that permits us to detect proteasome binding under the experimental conditions used. Finally, the interaction of the hPLIC-2 uba domain with the proteasome could involve a combination of direct interactions with core components of the proteasome and indirect interactions mediated through associated polyubiquitinated proteins.

To probe in greater detail whether the uba domain–proteasome binding is a direct interaction, the GST pull-down experiment was carried out using purified yeast proteasomes instead of total cell lysate. As shown in Figure 3C, the uba domain of hPLIC-2 was capable of interacting with purified yeast proteasomes, as was the hPLIC-2 ubl domain, whereas the uba domain of c-cbl did not bind. The interaction between human hPLIC-2 domains with yeast proteasomes as well as with human proteasomes (from HeLa cells) points to a conservation of binding sites on the proteasome and fits with the report that the closely related hPLIC-1 can rescue a yeast Dsk2-mediated phenotype in yeast (Kaye et al., 2000).

Because the hPLIC-2 ubl domain interacts with the S5a proteasomal cap subunit in vitro, and this interaction reflects ubl-proteasome binding (Walters et al., 2002), we tested whether the uba domain of hPLIC-2 could also target the same proteasomal subunit. In vitro synthesized 35S-labeled S5a was mixed with GST fusion proteins containing the ubl domain of hPLIC-2, the uba domain of hPLIC-2 and c-cbl, and SUMO-1. The pull down was analyzed by SDS-PAGE and exposed to film (Figure 3D). We found that GST-uba hPLIC-2 was capable of binding S5a, whereas GST-uba c-cbl and GST-SUMO could not. The interaction is not as avid as with GST-ubl hPLIC-2, reflecting the data in Figures 2 and 3, A and B. Because the binding depicted in Figure 3D was performed in a rabbit reticulocyte lysate extract, we cannot conclude from this experiment that the interaction between the uba domain of hPLIC-2 and S5a is direct. Nonetheless, the S5a interaction suggests that the S5a proteasomal cap subunit may also serve as a proteasomal binding site for the hPLIC-2 uba domain.

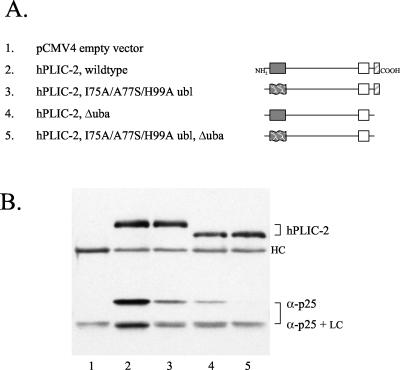

The identification of the uba domain of hPLIC-2 as a second proteasome interaction domain by in vitro pull-down experiments, suggested that it might account for the residual proteasome coimmunoprecipitation observed with full-length hPLIC-2 protein bearing the I75A/A77S/H99A ubl mutation as shown in Figure 1. Full-length wild-type hPLIC-2 was therefore compared for proteasome binding in cells with full-length hPLIC-2 containing the I75A/A77S/H99A triple mutation in the ubl domain, with wild-type hPLIC-2 lacking the C-terminal uba domain, and with hPLIC-2 containing the I75A/A77S/H99A ubl substitutions as well as lacking the uba domain. Both the triple ubl domain mutant and the uba domain deletion mutant demonstrated decreased binding compared with wild-type hPLIC-2 (32 and 13% of wild-type levels, respectively). The combination of the ubl triple substitution mutations with the uba domain deletion mutation eliminated proteasome binding (Figure 4, lane 5). Therefore, the N-terminal ubl domain and the C-terminal uba domain represent two independent proteasome binding sites in hPLIC-2.

Figure 4.

Both the ubl domain and the uba domain contribute to the interaction of hPLIC-2 with the proteasome. (A) List of expression vectors used. (B) The indicated constructs were transfected into HeLa cells and treated with proteasome inhibitor before cell lysis. Coimmunoprecipitation of proteasomes with hPLIC-2 was assayed by blotting for the α2 proteasomal core subunit and the FLAG tag. LC and HC depict the IgG light chain and heavy chain, respectively.

We next examined whether the ubl and uba domains of hPLIC-2 have a role in the degradation interference phenotype that we had identified previously (Kleijnen et al., 2000). HeLa cells are a cervical carcinoma-derived cell line in which p53 is a target for E6/E6AP mediated ubiquitination and degradation (Scheffner et al., 1990, 1993). We have previously shown that expression of full-length hPLIC interferes with p53 degradation, resulting in increased p53 levels (Kleijnen et al., 2000). As shown in Figure 5, expression of the hPLIC-2 mutant containing the I75A/A77S/H99A triple substitution in the ubl domain retained the ability to interfere with p53 degradation compared with the effect with wild-type hPLIC-2 (lanes 2 and 3). Therefore, the ubl-proteasome interaction is not by itself required for the hPLIC-2 interference phenotype. However, expression of the hPLIC-2 mutant containing the I75A/A77S/H99A triple ubl substitution in combination with the deletion of the uba domain failed to stabilize p53 levels (lane 4). Therefore, in the context of the mutant ubl domain, the hPLIC-2 uba domain is required for the proteolysis interference phenotype.

DISCUSSION

The uba domain is a three-helix structural motif, with the conserved residues involved in tieing the helices together (Dieckmann et al., 1998; Mueller and Feigon, 2002). Overall sequence homology is limited, and the sequence motif is found in a variety of proteins, many of which are involved in various aspects of ubiquitination (Hofmann and Bucher, 1996). It is not yet clear whether there are general functions for uba domains nor what those might be. One likely significant interaction ascribed to uba domains is its ability to bind to ubiquitin and multi-ubiquitin chains (Vadlamudi et al., 1996; Bertolaet et al., 2001b; Chen et al., 2001; Wilkinson et al., 2001; Chen and Madura, 2002; Funakoshi et al., 2002; Rao and Sastry, 2002). The uba domains of p62, Rad23, Dsk2, and Ddi1 are all capable of binding ubiquitin (as is the case for hPLIC-2; Figure 3B), and it is possible that the binding to ubiquitin or other ubiquitin family proteins may be a general uba domain attribute. Nevertheless, some uba domains have been shown to have interactions that are unique for that particular uba domain. For example, the human immunodeficiency virus vpr protein can bind to the second uba domain of hHR23A (Withers-Ward et al., 1997), but not to a number of other uba domains (Withers-Ward et al., 2000). Furthermore, the interaction that we describe in this article between the hPLIC-2 uba domain and the proteasome was not seen between the proteasome and either the c-cbl uba domain or the isopeptidase T uba domain. Other uba domain–protein interactions have been reported for the 3-methyladenine-DNA glycosylase (MPG protein) with hHR23A/B uba domains (Miao et al., 2000), the α1 subunit of GABAA receptor with the PLIC-1 uba domain (Bedford et al., 2001), and presenilins 1 and 2 with the hPLIC-1 uba domain (Mah et al., 2000). Furthermore, the uba domains in Rad23 and Ddi1 have been reported to be required for homo- and heterodimerization (Bertolaet et al., 2001a; Clarke et al., 2001).

In this report, we have used two different assays to look at the hPLIC-2–proteasome interaction: coimmunoprecipitation with tagged hPLIC-2 constructs in HeLa cells and pull-down experiments with bacterially expressed GST-hPLIC fusion constructs by using HeLa cell lysates. Both assays revealed two separate domains in hPLIC-2, the ubl domain and the uba domain, either of which can independently interact with proteasomes and both contribute to hPLIC-2–proteasome binding. The hPLIC-2 uba domain could be a direct proteasome interaction domain in that it can interact with purified yeast proteasomes by using GST-hPLIC-2 uba (Figure 3C). The conservation of hPLIC-2 binding to yeast and mammalian proteasomes is perhaps not unexpected because the closely related hPLIC-1 can complement a Dsk2 defect in yeast (Kaye et al., 2000).

An important question is to the nature of the hPLIC-2 uba domain binding the proteasome. Because uba domains can bind polyubiquitin chains, it is conceivable that polyubiquitin chains bound to the proteasome may mediate the uba domain–proteasome interaction via a ternary complex. We have tried to address this possibility by analyzing the GST pull downs for the presence of polyubiquitinated proteins as well as for proteasomal antigens (Figure 3B). All GST-uba domain constructs tested pull-down polyubiquitinated proteins from HeLa cell lysate. Importantly, only the hPLIC-2 uba domain pulls down proteasomal antigens, indicating that an interaction with polyubiquitin chains is by itself not sufficient for any uba domain to interact with the proteasome. The interaction that we detect between the hPLIC-2 uba domain and the proteasome could involve either direct interactions with core components of the proteasome, indirect interactions mediated through proteasome-associated polyubiquitinated proteins, or a combination of direct and indirect interactions. An important question is the identification of the binding site(s) for the hPLIC-2 uba domain on the proteasome.

The ubl domain binding sites in the proteasome have been mapped to the S5a proteasomal cap subunit in mammalian cells (Hiyama et al., 1999; Voges et al., 1999) and the Rpn1 proteasomal cap subunit in S. cerevisiae (Elsasser et al., 2002). We have previously reported that the hPLIC-2 ubl domain can bind S5a. Furthermore, the hPLIC-2 ubl domain interaction with S5a can be disrupted by specific point mutations within the ubl domain (Walters et al., 2002). These same mutations completely abolish the ability of the hPLIC ubl domain to pull down proteasomes from cell lysates. This indicates that the ubl-S5a binding activity reflects the way in which the hPLIC ubl domain binds the proteasome, and argues that the proteasomal S5a subunit is at least one of potentially several ubl-binding sites on the proteasome. Interestingly, we show in Figure 3D that in vitro translated S5a can interact with the hPLIC-2 uba domain as well. Even though rabbit reticulocyte lysate proteins are present, it is likely that this interaction is direct because the c-cbl uba domain does not interact (again reflecting the specificity of the hPLIC-2 uba domain–proteasome interaction shown in Figure 3, A and B). We conclude, therefore, that S5a seems to also be a proteasome-binding site for the hPLIC-2 uba domain. We have not yet determined whether the binding of the uba and ubl domains to S5a has any effect on each other's ability to bind S5a, perhaps competitively or cooperatively. Structural studies to identify the binding surfaces on S5a and the hPLIC-2 uba domain should help in determining the mechanistic consequences of their interactions.

We had previously observed that expression of full-length (but not the N-terminal fragment of) hPLIC in HeLa cells interferes with the ubiquitin-mediated degradation of several substrates, p53 and IκBα, but not with the ubiquitin-independent degradation of ornithine decarboxylase (Kleijnen et al., 2000). Furthermore, in the context of the full-length proteins, amino acid substitution mutations in the ubl domain that prevented ubl binding to proteasomes had no effect on the degradation interference phenotype. However, expression of an hPLIC-2 construct mutated in the ubl domain and also lacking the uba domain could not impair p53 degradation (Figure 5). Therefore, the uba domain is required for the degradation interference phenotype. Our findings are consistent with recent articles reporting that the Rad23 uba domain is essential for interfering with protein degradation upon Rad23 overexpression, possibly by interfering with polyubiquitin chain lengthening (Ortolan et al., 2000; Chen et al., 2001; Chen and Madura, 2002). Because Rad23 and the hPLIC proteins are structurally related containing both ubl and uba domains, it is possible that this Rad23 property is related to the phenotype that we see for the hPLIC proteins. The p53 degradation interference phenotype observed with hPLIC-2 could possibly result from interference with polyubiquitin chain lengthening, but this remains to be tested.

It is at present unclear how uba domain binding to one partner will affect binding to another. All uba domains of a variety of proteins tested so far seem to bind (poly)ubiquitin (Vadlamudi et al., 1996; Bertolaet et al., 2001b; Chen et al., 2001; Wilkinson et al., 2001; Chen and Madura, 2002; Funakoshi et al., 2002; Rao and Sastry, 2002). Indeed, the Schizosaccharomyces pombe version of Dsk2, Dph1, has been shown to bind multi-ubiquitin chains (Wilkinson et al., 2001). We have also found that the hPLIC-2 uba domain can bind polyubiquitin chains (Figure 3B). It will be important to determine whether the hPLIC-2 uba domain binding to proteasomes affects its binding to multi-ubiquitin. In addition, the uba domain of PLIC-1 has recently been shown to bind the GABAA receptor (Bedford et al., 2001). The authors show that the PLIC-1 uba domain–GABAA receptor interaction directly modulates GABAA receptor cell surface numbers and function. Given the high level of homology between hPLIC-1 and hPLIC-2, we assume that the uba domain of hPLIC-1 will also mediate an interaction with the proteasome. If so, would an interaction with the GABAA receptor interfere with PLIC-1 uba domain binding to the proteasome, or would it play a role in recruiting proteasomes to the receptor? Similarly, the uba domain of hPLIC-1/ubiquilin has been reported to bind presenilins 1 and 2, and this interaction affects presenilin protein concentration (Mah et al., 2000). The molecular details of how hPLIC-1 affects GABAA receptor function and presenilin function remain to be determined, but a direct role for proteasome function seems plausible.

Acknowledgments

We thank D. Leggett for advice on the yeast proteasome purification procedure. This research was supported by National Institutes of Health grants R37CA64888 (to P.M.H.) and R37CA64888S1 (to R.M.A.)

Article published online ahead of print. Mol. Biol. Cell 10.1091/mbc.E02–11–0766. Article and publication date are available at www.molbiolcell.org/cgi/doi/10.1091/mbc.E02-11-0766.

References

- Baumeister, W., Walz, J., Zuhl, F., and Seemuller, E. (1998). The proteasome: paradigm of a self-compartmentalizing protease. Cell 92, 367–380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bedford, F.K., Kittler, J.T., Muller, E., Thomas, P., Uren, J.M., Merlo, D., Wisden, W., Triller, A., Smart, T.G., and Moss, S.J. (2001). GABA(A) receptor cell surface number and subunit stability are regulated by the ubiquitin-like protein Plic-1. Nat. Neurosci. 4, 908–916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertolaet, B.L., Clarke, D.J., Wolff, M., Watson, M.H., Henze, M., Divita, G., and Reed, S.I. (2001a). UBA domains mediate protein-protein interactions between two DNA damage-inducible proteins. J. Mol. Biol. 313, 955–963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertolaet, B.L., Clarke, D.J., Wolff, M., Watson, M.H., Henze, M., Divita, G., and Reed, S.I. (2001b). UBA domains of DNA damage-inducible proteins interact with ubiquitin. Nat. Struct. Biol. 8, 417–422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bogyo, M., Shin, S., McMaster, J.S., and Ploegh, H.L. (1998). Substrate binding and sequence preference of the proteasome revealed by active-site-directed affinity probes. Chem. Biol. 5, 307–320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen, L., and Madura, K. (2002). Rad23 promotes the targeting of proteolytic substrates to the proteasome. Mol. Cell. Biol. 22, 4902–4913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen, L., Shinde, U., Ortolan, T.G., and Madura, K. (2001). Ubiquitin-associated (uba) domains in Rad23 bind ubiquitin and promote inhibition of multi-ubiquitin chain assembly. EMBO Rep. 2, 1–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciechanover, A. (1998). The ubiquitin-proteasome pathway: on protein death and cell life. EMBO J. 17, 7151–7160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarke, D.J., Mondesert, G., Segal, M., Bertolaet, B.L., Jensen, S., Wolff, M., Henze, M., and Reed, S.I. (2001). Dosage suppressors of pds1 implicate ubiquitin-associated domains in checkpoint control. Mol. Cell. Biol. 21, 1997–2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coux, O., Tanaka, K., and Goldberg, A.L. (1996). Structure and functions of the 20S and 26S proteasomes. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 65, 801–847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dieckmann, T., Withers-Ward, E.S., Jarosinski, M.A., Liu, C.F., Chen, I.S., and Feigon, J. (1998). Structure of a human DNA repair protein UBA domain that interacts with HIV-1 Vpr. Nat. Struct. Biol. 5, 1042–1047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elsasser, S., Gali, R., Schwickart, M., Larsen, C., Leggett, D.S., Mueller, B., Feng, M., Tuebing, F., Dittmar, G., and Finley, D. (2002). Proteasome subunit Rpn1 binds ubiquitin-like protein domains. Nat. Cell Biol. 4, 725–730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Funakoshi, M., Sasaki, T., Nishimoto, T., and Kobayashi, H. (2002). Budding yeast Dsk2p is a polyubiquitin-binding protein that can interact with the proteasome. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99, 745–750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henry, L., Baz, A., Chateau, M.-T., Caravano, R., Scherrer, K., and Bureau, J.P. (1997). Proteasome (prosome) subunit variations during the differentiation of myeloid U937 cells. Anal. Cell. Pathol. 15, 131–144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hershko, A., and Ciechanover, A. (1998). The ubiquitin system. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 1998, 425–479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hiyama, H., Yokoi, M., Masutani, C., Sugasawa, K., Maekawa, T., Tanaka, K., Hoeijmakers, J.H.J., and Hanaoka, F. (1999). Interaction of hHR23 with S5a. J. Biol. Chem. 274, 28019–28025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hochstrasser, M. (2000). Evolution and function of ubiquitin-like protein-conjugation systems. Nat. Cell Biol. 2, E153–E157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofmann, K., and Bucher, P. (1996). The UBA domain: a sequence motif present in multiple enzyme classes of the ubiquitination pathway. Trends Biochem. Sci. 21, 172–173. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jentsch, S., and Pyrowolakis, G. (2000). Ubiquitin and its kin: how close are the family ties? Trends Cell Biol. 10, 335–342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaye, F.J., Modi, S., Ivanovska, I., Koonin, E.V., Thress, K., Kubo, A., Kornbluth, S., and Rose, M.D. (2000). A family of ubiquitin-like proteins binds the ATPase domain of Hsp70-like Stch. FEBS Lett. 467, 348–355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleijnen, M.F., Shih, A.H., Zhou, P., Kumar, S., Soccio, R.E., Kedersha, N.L., Gill, G., and Howley, P.M. (2000). The hPLIC proteins may provide a link between the ubiquitination machinery and the proteasome. Mol. Cell 6, 409–419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leggett, D.S., Hanna, J., Borodovsky, A., Crossas, B., Schmidt, M., Baker, R.T., Walz, T., Ploegh, H., and Finley, D. (2002). Multiple associated proteins regulate proteasome structure and function. Mol. Cell 10, 495–507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luders, J., Demand, J., and Hohfeld, J. (2000). The ubiquitin-related BAG-1 provides a link between the molecular chaperones Hsc70/Hsp70 and the proteasome. J. Biol. Chem. 275, 4613–4617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mah, A.L., Perry, G., Smith, M.A., and Monteiro, M.J. (2000). Identification of ubiquilin, a novel presenilin interactor that increases presenilin protein accumulation. J. Cell Biol. 151, 847–862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miao, F., Bouziane, M., Dammann, R., Masutani, C., Hanaoka, F., Pfeifer, G., and O'Connor, T.R. (2000). 3-Methyladenine-DNA glycosylase (MPG protein) interacts with human RAD23 proteins. J. Biol. Chem. 275, 28433–28438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mueller, T.D., and Feigon, J. (2002). Solution structures of UBA domains reveal a conserved hydrophobic surface for protein-protein interactions. J. Mol. Biol. 319, 1243–1255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ortolan, T.G., Tongaonkar, P., Lambertson, D., Chen, L., Schauber, C., and Madura, K. (2000). The DNA repair protein Rad23 is a negative regulator of multi-ubiquitin chain assembly. Nat. Cell Biol. 2, 601–608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pickart, C.M. (2001). Mechanisms underlying ubiquitination. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 70, 503–533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rao, H., and Sastry, A. (2002). Recognition of specific ubiquitin conjugates is important for the proteolytic functions of the ubiquitin-associated domain proteins Dsk2 and Rad23. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 11691–11695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schauber, C., Chen, L., Tongaonkar, P., Vega, I., Lambertson, D., Potts, W., and Madura, K. (1998). Rad23 links DNA repair to the ubiquitin/proteasome pathway. Nature 391, 715–718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheffner, M., Huibregtse, J.M., Vierstra, R.D., and Howley, P.M. (1993). The HPV-16 E6 and E6-AP complex functions as a ubiquitin-protein ligase in the ubiquitination of p53. Cell 75, 495–505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheffner, M., Werness, B.A., Huibregtse, J.M., Levine, A.J., and Howley, P.M. (1990). The E6 oncoprotein encoded by human papillomavirus types 16 and 18 promotes the degradation of p53. Cell 63, 1129–1136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silva Pereira, I., Bey, F., and Scherrer, K. (1992). Two mRNAs exist for the Hs PROS-30 gene encoding a component of human prosomes. Gene 120, 235–242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tongaonkar, P., Chen, L., Lambertson, D., Ko, B., and Madura, K. (2000). Evidence for an interaction between ubiquitin-conjugating enzymes and the 26S proteasome. Mol. Cell. Biol. 20, 4691–4698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vadlamudi, R.K., Joung, I., Strominger, J.L., and Shin, J. (1996). p62, a phosphotyrosine-independent ligand of the SH2 domain of p56lck, belongs to a new class of ubiquitin-binding proteins. J. Biol. Chem. 271, 20235–20237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verma, R., Chen, S., Feldman, R., Schieltz, D., Yates, J., Dohmen, J., and Deshaies, R.J. (2000). Proteasomal proteomics: identification of nucleotide-sensitive proteasome-interacting proteins by mass spectrometric analysis of affinity-purified proteasomes. Mol. Biol. Cell 11, 3425–3439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voges, D., Zwickl, P., and Baumeister, W. (1999). The 26S proteasome: a molecular machine designed for controlled proteolysis. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 68, 1015–1068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walters, K.J., Kleijnen, M.F., Goh, A.M., Wagner, G., and Howley, P.M. (2002). Structural studies of the interaction between ubiquitin family proteins and the proteasome subunit S5a. Biochemistry 41, 1767–1777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilkinson, C.R., Seeger, M., Hartmann-Petersen, R., Stone, M., Wallace, M., Semple, C., and Gordon, C. (2001). Proteins containing the UBA domain are able to bind to multi-ubiquitin chains. Nat. Cell Biol. 3, 939–943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Withers-Ward, E.S., et al. (1997). Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Vpr interacts with HHR23A, a cellular protein implicated in nucleotide excision DNA repair. J. Virol. 71, 9732–9742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Withers-Ward, E.S., Mueller, T.D., Chen, I.S., and Feigon, J. (2000). Biochemical and structural analysis of the interaction between the UBA(2) domain of the DNA repair protein HHR23A and HIV-1 Vpr. Biochemistry 39, 14103–14112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie, Y., and Varshavsky, A. (2000). Physical association of ubiquitin ligases and the 26S proteasome. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97, 2497–2502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie, Y., and Varshavsky, A. (2002). UFD4 lacking the proteasome-binding region catalyses ubiquitination but is impaired in proteolysis. Nat. Cell Biol. 4, 1003–1007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]