Abstract

The G protein-coupled sst2 somatostatin receptor acts as a negative cell growth regulator. Sst2 transmits antimitogenic signaling by recruiting and activating the tyrosine phosphatase SHP-1. We now identified Src and SHP-2 as sst2-associated molecules and demonstrated their role in sst2 signaling. Surface plasmon resonance and mutation analyses revealed that SHP-2 directly associated with phosphorylated tyrosine 228 and 312, which are located in sst2 ITIMs (immunoreceptor tyrosine-based inhibitory motifs). This interaction was required for somatostatin-induced SHP-1 recruitment and activation and consequent inhibition of cell proliferation. Src interacted with sst2 and somatostatin promoted a transient Gβγ-dependent Src activation concomitant with sst2 tyrosine hyperphosphorylation and SHP-2 activation. These steps were abrogated with catalytically inactive Src. Both catalytically inactive Src and SHP-2 mutants abolished somatostatin-induced SHP-1 activation and cell growth inhibition. Sst2–Src–SHP-2 complex formation was dynamic. Somatostatin further induced sst2 tyrosine dephosphorylation and complex dissociation accompanied by Src and SHP-2 inhibition. These steps were defective in cells expressing a catalytically inactive Src mutant. All these data suggest that Src acts upstream of SHP-2 in sst2 signaling and provide evidence for a functional role for Src and SHP-2 downstream of an inhibitory G protein-coupled receptor.

INTRODUCTION

Somatostatin is a widely expressed hormone that exerts pleiotropic biological actions, including neurotransmission, inhibition of hormonal and hydroelectrolytic secretions, and cell proliferation. This neuropeptide acts by interacting with specific receptors that belong to the G protein-coupled seven-transmembrane domain receptor (GPCR) superfamily. Five subtypes of somatostatin receptors have been thus far cloned (sst1–5). They mediate a variety of signal transduction pathways, including inhibition of adenylate cyclase and guanylate cyclase, modulation of ionic conductance channels and protein phosphorylation, activation of mitogen-activating protein kinase and phospholipase C (Meyerhof, 1998).

Among somatostatin receptors, sst2 has been found to play a critical role in the negative control of cell growth and to act as a tumor suppressor gene for pancreatic cancer (Benali et al., 2000). The signaling pathways, for sst2 receptor-mediated cell growth inhibition have not been fully elucidated. We have shown that sst2 receptor mediates cell growth inhibitory effect by a mechanism involving the stimulation of a tyrosine phosphatase we identified as SHP-1, a nontransmembrane tyrosine phosphatase that contains two Src homology 2 (SH2) domains. SHP-1 transiently associates with sst2 receptor via the G protein Gαi3 and becomes activated in response to somatostatin (Buscail et al., 1995; Lopez et al., 1997). Activated SHP-1 dephosphorylates distinct signaling molecules, including growth factor receptors and neuronal nitric-oxide synthase and promotes p27Kip1 induction and cell cycle arrest (Bousquet et al., 1998; Pages et al., 1999; Lopez et al., 2001).

SHP-2, another member of the SH2-containing tyrosine phosphatase family, has been shown to associate with activated cytokine and growth factor receptors, platelet/endothelial cell adhesion molecule-1 (PECAM-1) and immunoreceptors (Kazlauskas et al., 1993; Tamir et al., 2000; Newman et al., 2001). SHP-2 also associates with signaling proteins such as Grb2 associated binder 1 (Gab1) and 2 (Gab2) (Ali, 2000), insulin receptor substrate-1 (Myers et al., 1998), and the SHP substrate-1/SIRPα (Fujioka et al., 1996). SHP-2 plays a critical role for transducing various signals that lead to cell growth, differentiation, or migration (reviewed in Neel and Tonks, 1997; Stein-Gerlach et al., 1998; Tamir et al., 2000). It mediates activation of the Ras-mitogen-activated protein (MAP) kinase cascade in response to a variety of growth factors and biological evidence that SHP-2 is an important component of growth factor signaling pathways has been evidenced by multiple genetic studies as well as studies with both negative and activated mutants (reviewed in Tonks and Neel, 2001). However, SHP-2 may also have negative regulatory influences. For instance, in Chinese hamster ovary (CHO) cells expressing insulin receptors, SHP-2 attenuates insulin metabolic responses by reducing insulin receptor substrate-1 tyrosine phosphorylation (Myers et al., 1998). The PD-1 immunoreceptor negatively regulates the B cell receptor by recruiting SHP-2 and dephosphorylating BCR effector molecules (Okazaki et al., 2001). SHP-1 and SHP-2 mediate their intracellular signals by interacting with tyrosine-phosphorylated molecules bearing consensus sequence (I/V/L/S-x-Y-x-x-L/V) named immunoreceptor tyrosine-based inhibitory motif (ITIM) and initially observed in inhibitory immunoreceptors. On tyrosine phosphorylation, ITIM-bearing molecules recruit SH2-containing phosphatase, activate it, and consequently, inhibit phosphorylation-dependent signaling cascades (reviewed in Long, 1999; Blery et al., 2000).

Little is known about the role of SHP-2 in the regulation of G protein-coupled receptor signaling. SHP-2 associates with the G protein-coupled AT1 and is required for JAK2 activation, in response to angiotensin in vascular smooth muscle cells (Marrero et al., 1998). SHP-2 is involved in α-thrombin–mediated cell growth in fibroblast cells (Rivard et al., 1995) and participates in somatostatin-induced activation of the Ras/Raf-1/MAP kinase pathway via the sst1 receptor (Florio et al., 1999). Recently, we reported a direct interaction between the bradykinin B2 receptors and SHP-2, which is necessary to mediate the antiproliferative effect of bradykinin (Duchene et al., 2002). Whether SHP-2 participates in sst2 receptor signaling is not known. The purpose of this study was to investigate the role of SHP-2 in sst2-mediated cell growth inhibition signaling. We demonstrated a direct association between sst2 receptor and SHP-2 SH2 domains and we found a novel mechanism for SHP-2 function by working downstream of Src kinase in promoting somatostatin-mediated activation of SHP-1.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials

RC-160, a somatostatin analog, was a generous gift from A.V. Schally (Tulane University, New Orleans, LA). [Tyr11]somatostatin 14 and somatostatin 14 were generous gifts from C. Bruns (Novartis, Basel, Switzerland). Hybond ECL nitrocellulose membrane was purchased from Gelman Instrument (Ann Arbor, MI). Streptavidin-coated chips (Sensor Chip SA) were obtained from BIAcore (Uppsala, Sweden). Biotinylated phosphorylated or nonphosphorylated ITIM peptides, corresponding to the sequence surrounding Y228 and Y312 in the mouse sst2 receptor: biotinyl-KKLCpYLFIIIKVKS (ITIM-pY228), biotinyl-KKLCYLFIIIKVKS (ITIM-Y228), and biotinyl-SCANPILpYAFLSDNFKK (ITIM-pY312), biotinyl-SCANPILYAFLSDNFKK (ITIM-Y312), corresponding to the sequence surrounding Y304 in the human KIR (killer-cell inhibitory receptor): biotinyl-DPQEVTYAQLNHC (ITIM-pY304), biotinyl-DPQEVTYAQLNHC (ITIM-Y304) were from Neo-system (Strasbourg, France). Nucleotides for site-directed mutagenesis were purchased from MWG-Biotech (Ebersberg, France).

Plasmids and Antibodies

Point mutations in the murine sst2 receptor (Y228F; Y312F and Y228/312F) were generated by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) mutagenesis and all mutations were confirmed by DNA sequence analysis. The sst2 mutant receptor cDNAs were subcloned into pCMV6c vector. The catalytically inactive Src containing vector corresponding to a 1.7-kb insert coding for chicken inactive Src kinase (Src K295R) in pSGT vector was a generous gift from S. Roche (Centre deRecherches deBiochimie macromoléculaire, CNRS Montpelier, France). The catalytically inactive SHP-2 (C459S) mutant (Rivard et al., 1995) subcloned in pCDNA3 vector was a kind gift from C. Nahmias (ICGM, hôpital Cochin, Paris, France). The vector coding for truncated βARK1-CT fusion protein construct (671–689) was a generous gift from R.J. Lefkowitz (Duke University Medical Center, Durham, NC). Polyclonal anti-sst2 antibodies were generated in rabbits immunized with peptides corresponding to either amino acid residues 191–206 of mouse sst2 or residues 339–359 of the rat protein, as previously described (Gu and Schonbrunn, 1997; Lopez et al., 1997). Monoclonal antibodies against SHP-1, SHP-2 and phospho-tyrosine residues (PY-20) were purchased from Transduction Laboratories (France Biochem, France). Monoclonal anti-Src antibody (antibody-1) was purchased from Calbiochem, Inc. Monoclonal anti-Fyn and anti-Lyn antibodies were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (TEBU, France). Monoclonal anti-Yes antibody was a generous gift from S. Roche (Centre de Recherches de Biochimie macromoléculaire, Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique, Montpellier, France).

Cell Culture and Cell Growth Assay

Rat pancreatic tumor AR4-2J cells were cultured in DMEM containing 7.5% fetal calf serum (FCS) and hamster glucagonoma InR1G9 cells in RPMI 1640 medium containing 10% FCS. CHO (DG44 variant) cells and their derivatives [CHO/sst2 and CHO/sst2-SHP-2(C/S)] were cultured in minimal essential medium (αMEM) containing 7.5% FCS and geneticin (G418; 200 μg/ml), as described previously (Buscail et al., 1995). COS-7 cells were grown in DMEM supplemented with 5% FCS. For cell treatment, CHO cells were plated in 100-mm dishes (7 × 105 cells/dish) in αMEM containing 7.5% FCS, and after an overnight attachment phase, cells were cultured for 48 h. After removal of the medium, cells were incubated for indicated times in αMEM containing 7.5% FCS in the presence or absence of 1 nM RC-160 at 37°C. For the cell growth assay, CHO cells and their derivatives were plated in 35-mm dishes (50 × 103 cells/ml) and cultured for 24 h in αMEM or in αMEM containing 7.5% FCS with or without 1 nM RC-160. Cell growth was measured at the indicated times by counting cells with a Coulter counter model ZM (Beckman Coulter, Fullerton, CA), as described previously (Buscail et al., 1994).

Transfections

The 1.2-kb XbaI fragment of mouse sst2 gene subcloned into pCMV6c vector was stably cotranfected in CHO cells by using the Lipofectin reagent with pSV2neo (CHO/sst2 cells) as described previously (gift from G.I. Bell, Howard Hughes Medical Institute, University of Chicago, Chicago, IL; T. Reisine, University of Pennsylvania, School of Medicine, Philadelphia, PA) or with the catalytically inactive SHP-2 (C459S) mutant [CHO/sst2-SHP-2(C/S) cells] (Yamada et al., 1992). Stable transfectants were selected in αMEM containing G418 at 600 μg/ml and were screened for sst2 expression by somatostatin binding by using 125I-[Tyr11]somatostatin, as described previously (Buscail et al., 1994). For transient transfections, wild-type sst2, mutant receptor, or Src (K295R) plasmid DNAs were transiently transfected into COS-7 cells by using the DEAE/dextran method, as described previously (Buscail et al., 1994) or in CHO cells by using FuGENE6 reagent according to the manufacturer's instructions (Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN). Cells were plated in 100-mm diameter dishes at 1.5 × 106 (COS-7 cells) or 0.7–1 × 106 (CHO cells) cells/dish, allowed to adhere for 24 h, and then transfected with 2 μg (COS-7 cells) or 4 μg (CHO cells) of each plasmid for 5 h in serum-free medium. Transfection efficiencies were determined by transfection of a plasmid encoding green fluorescent protein in CHO cells. Expression was detected by fluorescence microscopy (image-analysis system Visio-Lab 2000; Biocom, Paris, France) and was observed in ∼34% of cells. COS-7 cells were then transferred to six-well culture plates at a density of 1 × 105 cells/well for 24 h and assayed for 125I-[Tyr11]somatostatin binding. Transfected CHO cells were transferred into 35-mm dishes for cell growth assay or 100-mm dishes for phosphatase or kinase assays. Aliquots of cell culture were kept for Western analysis of protein expression levels.

Binding of 125I-[Tyr11]Somatostatin to Transfected CHO and COS-7 Cells

CHO or COS-7 cells were incubated in Krebs-HEPES buffer containing 0.1 mg/ml soybean trypsin inhibitor, 0.2% bovine serum albumin for 2 h at room temperature with increasing concentration of 125I-[Tyr11]somatostatin, as described previously (Buscail et al., 1994). Nonspecific binding was determined in the presence of 1 μM somatostatin. Binding data were determined using the nonlinear, least squares, curve-fitting computer program Ligand (Munson and Rodbard, 1980), and GraphPad Prism (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA).

Expression of Glutathione S-Transferase (GST)-SH2 Domains Fusion Proteins

The GST fusion proteins containing the SH2 domains of SHP-1 and SHP-2 were generated from the murine phosphatase cDNA, as described previously (D'Ambrosio et al., 1995) and expressed by induction of Escherichia coli DH5α with 1 mM isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside. Expressed fusion proteins were isolated by procedures described previously (Vely et al., 1997). Protein concentrations were determined by the modified Bradford method (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA).

Surface Plasmon Resonance

The binding kinetics of GST fusion proteins to immobilized peptides were measured with a BIAcore 2000 biosensor instrument (BIAcore AB). Binding of GST fusion protein mass to immobilized peptide was observed in terms of resonance units (RU) (1000 RU = 1 ng of protein bound/mm2 of flow cell surface). The running buffer was Hanks' balanced salt buffer and the same buffer was used for diluting samples before injection. Synthetic biotinylated peptides were immobilized onto streptavidin-coated carboxymethylated dextran chips. For sst2-GST fusion protein interaction measurements, chip contains four flow cells; flow cells 2 and 4 were coated with ITIM-pY228 and ITIM-pY312 peptides, respectively. Flow cells 1 and 3 were coated with nonphosphorylated corresponding peptides. Fifty RU of peptides were coupled to each BIAcore flow cell. To measure binding interactions, the GST fusion proteins, at different concentrations (10–400 nM), were passed over the immobilized peptide surface at a flow rate of 20 μl/min at 25°C. Similar experiments were performed for KIR-GST fusion protein interaction measurements, flow cells 1 and 2 being coated with 50 RU of Y304 and pY304 peptides, respectively. After each binding assay, flow cells were regenerated by short pulses of 5 μl of 0.01% SDS. To assess whether any degradation of the chip occurred between the experiments, the level of phosphotyrosine residues on phosphorylated peptides was checked with an anti-phosphotyrosine antibody. The sensorgrams generated by each GST fusion protein's binding to the tyrosine phosphorylated peptides were adjusted by subtracting the binding to the nonphosphorylated peptide. Binding constants were determined from the titration curves by using a global fitting routine provided by BIAcore (BIAevaluation 3.1).

Immunoprecipitation and Immunoblotting

Cells were washed twice and lysed for 30 min at 4°C in buffer A (50 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.4, 140 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 0.1 mg/ml soybean trypsin inhibitor, 0.1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride) supplemented with 1.5% 3-[(3-cholamidopropyl)dimethylammonio]propanesulfonate and 0.5 mM sodium orthovanadate. Soluble proteins were collected by centrifugation and incubated for 3 h at 4°C with primary antibody–protein A-Sepharose complexes. Immunoprecipitates were washed three times with buffer A and resuspended in either sample buffer for immunoblotting or tyrosine phosphatase buffer for tyrosine phosphatase assay. For immunoblotting, immunoprecipitated proteins were analyzed by SDS-PAGE. Western blotting was performed using standard techniques. Immunoreactive proteins were visualized by the ECL immunodetection system (Pierce Chemical, Rockford, IL) and quantified by image analysis using a Biocom apparatus (Biocom).

Tyrosine Phosphatase Assay

Immunoprecipitated SHP-1 or SHP-2 proteins were resuspended in tyrosine phosphatase buffer containing 50 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.4, 0.05% SDS, 1 mg/ml bovine serum albumin, 0.5 mg/ml bacitracin, 5 mM dithiothreitol, 100 μM genistein, and 1 μM PP2. The substrate poly(Glu-Tyr) was phosphorylated with [γ-33P]ATP. The reaction was initiated by the addition of 33P-labeled poly(Glu-Tyr) and allowed to proceed for 10 min at 30°C as described previously (Buscail et al., 1994). One unit of tyrosine phosphatase activity was defined as the amount of phosphatase that released 1 pmol of phosphate per minute per milligram of solubilized protein. SHP-1 and SHP-2 phosphatase activities were normalized to the amount of total respective tyrosine phosphatase protein immunoprecipitated at each time point.

Src Kinase Assay

Cells were washed with buffer A (50 mM HEPES pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 10 mM EDTA, 10 mM Na4P2O7, 100 mM NaF, 2 mM orthovanadate), and cell lysates were prepared in lysis buffer (buffer A containing 1% Triton X-100, 0.5 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 20 μM leupeptin, 10 μg/ml aprotinin) for 15 min at 4°C. Lysates were immunoprecipitated on Sepharose G proteins coupled to monoclonal Src antibody. Immunoprecipitates were washed twice with lysis buffer and three times with Tris-buffered saline (25 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 0.2 mM orthovanadate) and resuspended in 10 μl of kinase buffer containing 20 mM HEPES, pH 7.5, 10 mM MnCl2, 1 mM dithiothhreitol, and 5 μM acid-denatured enolase as exogenous substrate. Kinase reactions were initiated by addition of 3.75 μM ATP, 5 μCi of [γ-32P]ATP in a total volume of 40 μl. After incubation at 30°C for 10 min, phosphorylation was stopped by addition of 4× samples buffer and boiled at 95°C for 5 min. Samples were then analyzed by SDS-PAGE. Src kinase activity was normalized to the amount of total respective kinase protein at each time point.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical comparison between RC-160–treated or untreated cells was performed using Student's paired t test: *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01.

RESULTS

SHP-2 Directly Associates with sst2 via Phosphorylated ITIMs

To assess whether the endogenously expressed SHP-2 tyrosine phosphatase interacts with sst2, we first analyzed SHP-2 association with sst2 in CHO/sst2 cells after sst2 immunoprecipitation with anti-sst2 antibody. CHO/sst2 cells expressed sst2 as a protein of 95 kDa detected by immunoblotting as reported previously (Lopez et al., 1997). The 68-kDa SHP-2 protein was coimmunoprecipitated with the sst2 protein (Figure 1A). Similar results were observed when the cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with anti-SHP-2 antibody. To determine whether sst2–SHP-2 association also occurs in physiological conditions when these proteins are not overexpressed, we then analyzed other cell lines such as hamster glucagonoma InR1G9 and rat pancreatic tumor AR4-2J cell lines, and mouse pancreatic acini, which expressed endogenous sst2. Immunoprecipitation and Western blotting analysis revealed that sst2–SHP-2 association was present in all tested cell models (Figure 1B).

Figure 1.

Association of SHP-2 with sst2. (A) CHO/sst2 cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with either anti-sst2, anti-SHP-2 antibodies, or preimmune serum (PI). Immune complexes were analyzed by Western blotting with anti-sst2 or anti-SHP-2 antibodies. (B) Mouse pancreatic acinar extracts and InR1G9 or AR4-2J cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with anti-sst2 antibodies and immunoblotted with anti-SHP-2 and anti-sst2 antibodies. Immunoblots are representative of three separate experiments.

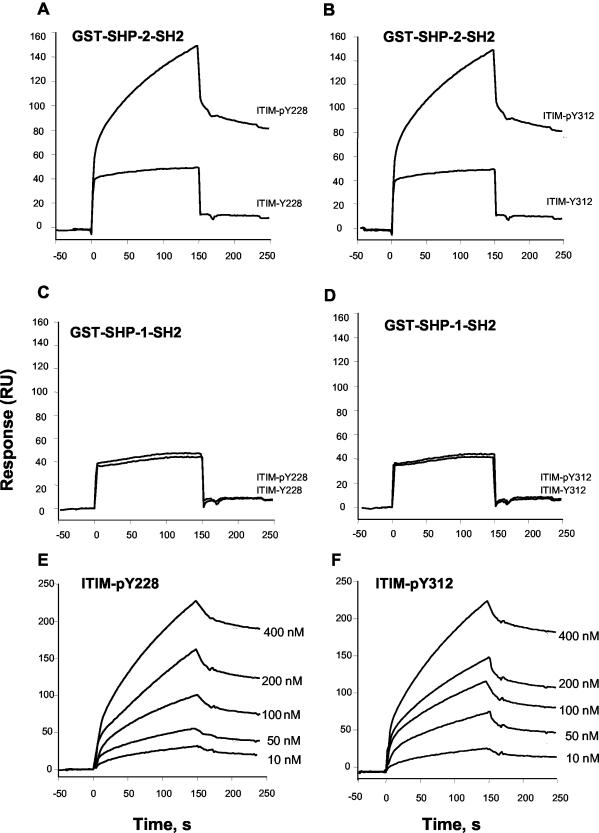

SHP-2 can interact via its SH2 domains with phosphorylated tyrosine containing consensus ITIM (I/V/L/S-x-Y-x-x-L/V). Sequence analysis revealed that sst2 contains two ITIM-like sequences, one in the third intracellular loop (L-C-Y228-L-F-I) and the other in the C-terminal tail (I-L-Y312-A-F-L). Therefore, we questioned whether SHP-2 directly interacts with sst2. For this purpose, recombinant GST fusion proteins, encompassing the amino- and carboxy-terminal SH2 domains of either SHP-2 (termed GST-SHP-2-SH2) or SHP-1 (termed GST-SHP-1-SH2) were purified. The surface plasmon resonance technique was used to investigate putative real-time interactions between these GST fusion proteins and phosphorylated versus nonphosphorylated peptides, corresponding to both sst2 ITIM sequences (ITIM-pY228 and ITIM-Y228, or ITIM-pY312 and ITIM-Y312). As a positive control, GST fusion proteins were first tested on KIR ITIM peptides, as described previously (Olcese et al., 1996) (our unpublished data). The biotinylated phosphotyrosine-containing peptides, ITIM-pY228 and ITIM-pY312, as well as the nonphosphorylated control peptides, were attached to streptavidin-coated chips and representative sensorgrams for the binding of the GST fusion proteins (100 nM) to immobilized peptides are shown in Figure 2, A–D. Binding of phosphorylated ITIM-pY228 and ITIM-pY312 peptides was observed when the recombinant GST-SHP-2-SH2 was used (Figure 2, A and B). In contrast, no binding was observed in the presence of the GST-SHP-1-SH2 (Figure 2, C and D) fusion protein, supporting the idea that phosphorylated Y228 and Y312 specifically interact in vitro with SHP-2 SH2 domains. As shown in Figure 2, A–D, nonphosphorylated peptides failed to associate with GST fusion proteins. GST itself did not bind to any of the test surfaces and none of the GST-SH2 domains fusion proteins bound significantly to the control biosensor chip surface (data not shown). The real-time association and dissociation kinetics of GST-SHP-2-SH2 with each phosphorylated peptide was then studied with increasing concentrations (10–400 nM) of GST-SHP-2-SH2 fusion protein. Representative sensorgrams of ITIM-pY228 and ITIM-pY312 peptides binding to the GST-SHP-2-SH2 protein are shown in Figure 2, E and F, respectively. Constant kinetics derived from binding data, obtained with the two tyrosine-phosphorylated peptides, is presented in Table 1. GST-SHP-2-SH2 bound to the ITIM-pY228 and ITIM-pY312 peptides with similar high affinities. Interaction analysis between SHP-2 SH2 domains and phosphorylated forms of sst2 ITIM peptides showed that SHP-2 SH2 domains directly interact in vitro with sst2 ITIM-pY228 and ITIM-pY312 sequences, this interaction being specific and of high affinity.

Figure 2.

Overlay sensorgrams for surface plasmon resonance analysis of GST-SHP-2-SH2 fusion protein binding to immobilized pITIM sst2 receptor peptides. The indicated GST, GST-SHP-2-SH2 (A and B), GST-SHP-1-SH2 (C and D), fusion proteins were examined for binding to sst2 biotinylated ITIM-pY228 and ITIM-pY312, and real-time binding responses were plotted as RU signals relative to time. The sensorgrams shown are for 100 nM fusion proteins. (E and F) GST-SHP-2-SH2 were incubated at concentrations ranging from 10 to 400 nM with immobilized biotinylated phosphorylated ITIM-pY228 and ITIM-pY312 of sst2. Results are expressed as RU as a function of time.

Table 1.

Kinetic and equilibrium constants of the interaction between the sst2-phosphorylated ITIM peptides with GST-SHP-2-SH2 and GST-SHP-1-SH2

| kon (105) (M-1 s-1) | koff (10-3) (s-1) | Kd (nM) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| GST-SHP-2-SH2 | |||

| ITIM-pY228 | 0.99 ± 0.01 | 1.75 ± 0.09 | 18.6 ± 1.9 |

| ITIM-pY312 | 1.74 ± 0.71 | 1.68 ± 0.38 | 14.9 ± 2.2 |

| GST-SHP-1-SH2 | |||

| ITIM-pY228 | ND | ND | |

| ITIM-pY312 | ND | ND |

ND, not detectable.

Binding constants were calculated from SPR data over all tested concentrations of fusion proteins as described in MATERIALS AND METHODS. Mean ± SE of three experiments.

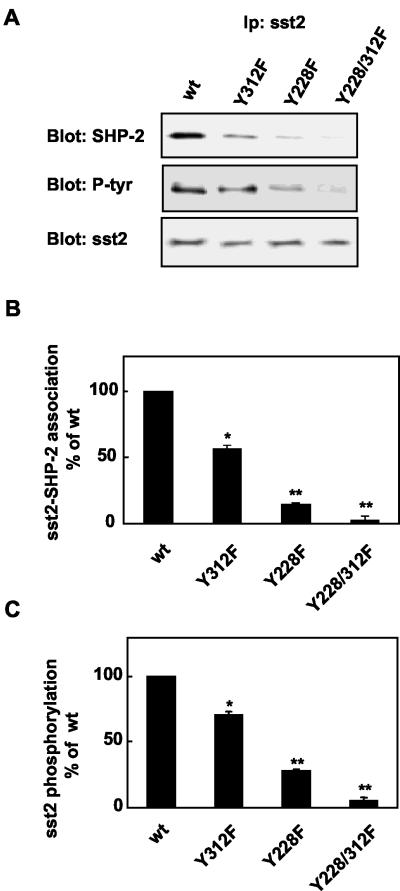

To evaluate the possibility of in vivo involvement of both tyrosines (Y228 and Y312) in sst2 interaction with SHP-2 SH2 domains, we constructed sst2 mutants harboring substitution of Y228 and Y312 with phenylalanine residues (Y228F, Y312F and Y228/312F). We transiently transfected COS-7 cells with the wild-type or mutated sst2. Binding analysis using 125I-[Tyr11]somatostatin 14 as a tracer revealed that sst2 Y312F and Y228/312F mutants displayed similar constant affinity and maximal binding capacity as wild-type sst2, whereas Y228F exhibited a decrease in affinity for somatostatin and an increase in binding capacity compared with wild-type sst2 (Table 2). Binding analysis was also performed in CHO cells transfected with wild-type and sst2 Y228/312F mutant. In these cells also, constant affinities of [125Tyr11]somatostatin 14 and maximal binding capacities were similar for wild-type and mutated sst2 (Kd = 4.4 × 10–10 M and 1.1 × 10–9 M; Bmax = 0.12 and 0.17 pmol/106 cells, respectively). The ability of mutant sst2 to interact with endogenous SHP-2 in CHO cells transiently transfected with either the wild-type sst2 or Y228F or Y312F or Y228/312F mutant sst2 was investigated by measuring levels of SHP-2 in sst2 immunoprecipitates by using an anti-SHP-2 immunoblot. Correct expression of each construct (sst2 or Y228F, Y312F and Y228/312F) was confirmed by immunoblotting with anti-sst2 antibody. As expected in CHO cells expressing the wild-type sst2, anti-sst2 antibodies immunoprecipitated SHP-2 (Figure 3A). In contrast, in the sst2 Y312F- and Y228F-expressing cells, the amount of SHP-2 associated with sst2 was decreased by 45 ± 2.5 and 86 ± 2%, respectively, compared with wild-type sst2. In cells expressing sst2 Y228/312F, SHP-2 was not significantly associated with sst2 in the immunoprecipitates (Figure 3B). These results suggest that both sst2 Y228 and Y312 residues mediate in vivo sst2 binding to SHP-2. Mutation of both tyrosine residues 228 and 312 dramatically suppresses SHP-2–sst2 association.

Table 2.

Binding parameters of 1251-[Tyr11]somatostatin 14 binding to sst2 in transfected COS-7 cells

| Kd (nM) | Bmax (pmol/106cells) | |

|---|---|---|

| sst2 | 1.71 ± 0.79 | 0.52 ± 0.09 |

| Y228F | 8.72 ± 2.89* | 1.33 ± 0.33* |

| Y312F | 4.13 ± 1.92 | 0.9 ± 0.39 |

| Y228/312F | 3.43 ± 0.4 | 0.56 ± 0.16 |

Data represent mean ± SE obtained from three separate experiments performed in duplicate.

Figure 3.

Influence of sst2 tyrosine residues 228 and 312 on sst2-SHP-2 association and sst2 tyrosine phosphorylation. (A) CHO cells were transfected with wild-type sst2 (wt) or mutants (Y312F, Y228F, or Y228/312F). Sst2 immunoprecipitates were subjected to immunoblotting with anti-SHP-2, anti-phosphotyrosine, or anti-sst2 antibodies. (B) Densitometric analysis of sst2–SHP-2 association, normalized to sst2 levels (A, bottom). (C) Densitometric analysis of sst2 phosphorylation presented in A (middle), normalized to sst2 levels. Data are plotted as percentage of control values obtained from wild-type sst2 vector-transfected cells. Data represent the mean ± SE of three independent experiments.

Because SHP-2 binding to sst2 is thought to be mediated through interaction with phosphorylated Y228 and Y312 residues, we then examined the level of sst2 tyrosine phosphorylation in sst2 immunoprecipitates derived from wild-type or mutated sst2 expressing cells. Wild-type sst2 was highly phosphorylated, whereas the phosphorylation of sst2 Y312F was partially decreased (71 ± 2.5% of wild-type) and the phosphorylation of sst2 Y228F and Y228/312F were even more reduced (28 ± 2.0 and 5 ± 2.5% of wild-type, respectively) (Figure 3, A and C). These results indicate that sst2 is tyrosine phosphorylated in the basal state, Y228 being the major site of sst2 tyrosine phosphorylation and that the loss in sst2 tyrosine phosphorylation affects SHP-2 binding to sst2.

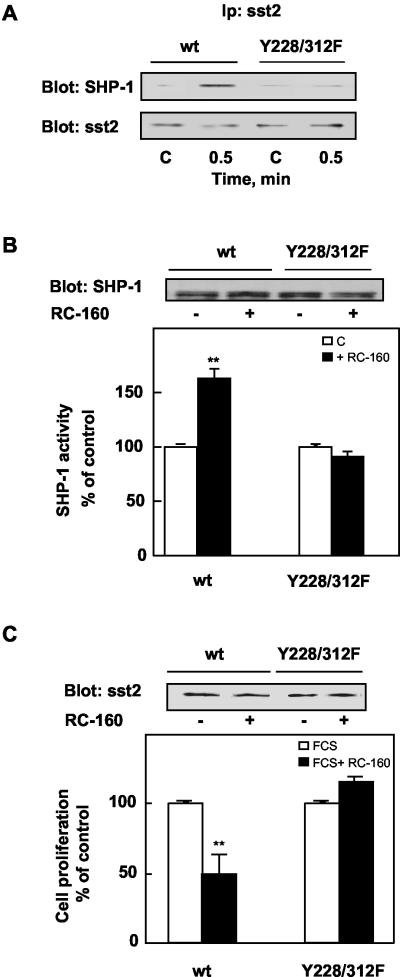

sst2–SHP-2 Association Is Required to Transduce sst2-mediated SHP-1 Activation and Inhibitory Growth Signal

The demonstration that SHP-2 directly interacts with sst2 suggests a possible role for SHP-2–sst2 interaction in sst2 signaling. We previously demonstrated that in CHO/sst2 cells, activation of sst2 by somatostatin analog results in a rapid recruitment of SHP-1 by sst2 accompanied by an increase of SHP-1 activity, the stimulation of the enzyme being required for sst2-mediated antimitogenic signaling (Lopez et al., 1997). To establish whether sst2–SHP-2 association is required for sst2 signaling, CHO cells were transiently transfected with vectors expressing SHP-1 and wild-type or Y228/312F sst2 and treated with RC-160 somatostatin analog (Buscail et al., 1995). We first examined the role of SHP-2–sst2 association on the interaction of SHP-1 with sst2 by measuring the level of SHP-1 in sst2 immunoprecipitates. In cells expressing wild-type sst2, SHP-1 was weakly associated with sst2 at the basal state and RC-160 treatment for 30 s resulted in an increase of SHP-1 amount immunoprecipitated with anti-sst2 antibodies, as shown previously (Lopez et al., 1997). In cells expressing mutated sst2, the low basal association of SHP-1 with sst2 was also observed, supporting surface plasmon resonance data and suggesting that SHP-1 associated with sst2 independently of Y228 and Y312 residues. Nevertheless, SHP-1–sst2 complex formation was not enhanced upon addition of RC-160, supporting the notion that SHP-2–sst2 complex is required for RC-160–mediated recruitment of SHP-1 (Figure 4A). We then investigated the role of SHP-2–sst2 association on SHP-1 activity. Lysates from CHO cells expressing wild-type or Y228/312F sst2 and treated with or without RC-160 were immunoprecipitated with an anti-SHP-1 antibody and subjected to immune complex tyrosine phosphatase activity. As reported previously (Lopez et al., 1997, 2001), in cells expressing wild-type sst2, RC-160 treatment induced a stimulation of SHP-1 activity. This effect was completely abrogated in sst2 Y228/312F expressing cells (Figure 4B). Finally, we then investigated the role of SHP-2–sst2 association in somatostatin analog-induced inhibition of cell proliferation. Overexpressing sst2 and sst2 Y228/312F CHO cells were treated with or without 1 nM RC-160 for 24 h, and cell growth was measured. RC-160 inhibited the growth of wild-type sst2 expressing cells by ∼50%, as observed previously (Lopez et al., 1997), whereas it did not affect the growth of sst2 Y228/312F-expressing cells (Figure 4C). These data demonstrate a critical role for sst2 tyrosine residues 228 and 312 in transducing sst2 growth inhibitory signal and suggest that formation of sst2–SHP-2 complexes is required for RC-160–mediated SHP-1–sst2 association, SHP-1 activation, and consequent growth inhibition.

Figure 4.

Sst2 tyrosine residues 228 and 312 are required for RC-160–induced sst2–SHP-1 association, SHP-1 activity, and cell growth inhibition. (A) Influence of sst2 tyrosine residues 228 and 312 on RC-160–induced sst2–SHP-1 association. CHO cells transiently expressing wild-type (wt) or Y228/312F sst2 were treated for 30 s with 1 nM RC-160 at 37°C. Sst2 immunoprecipitates were analyzed by Western blotting with anti-SHP-1 and anti-sst2 antibodies. Immunoblots are representative of three separate experiments. (B) Influence of sst2 tyrosine residues 228 and 312 on RC-160–induced SHP-1 activity. Cells were treated for 20 min without (open bars) or with 1 nM RC-160 (closed bars) at 37°C. SHP-1 immunoprecipitates were analyzed by immunoblotting with anti-SHP-1 antibodies (top) and assayed for phosphatase activity (bottom). Results are expressed as percentage of phosphatase activity obtained from cells at time 0 (c). Data represent the mean ± SE of three independent experiments made in duplicate. Basal SHP-1 activity of cells expressing wild-type sst2 and Y228/312F were 0.58 ± 0.09 and 0.72 ± 0.06 U, respectively. (C) Influence of sst2 tyrosine residues 228 and 312 on RC-160–induced cell growth inhibition. Cells were treated for 24 h in the presence of FCS without (open bars) or with 1 nM RC-160 (closed bars). Cell lysates were examined for sst2 wt and Y228/312F protein expression by Western blotting with anti-sst2 antibodies (top). Results are expressed as percentage of cell proliferation obtained from untreated cells (bottom). Data represent the mean ± SE of four independent experiments made in triplicate.

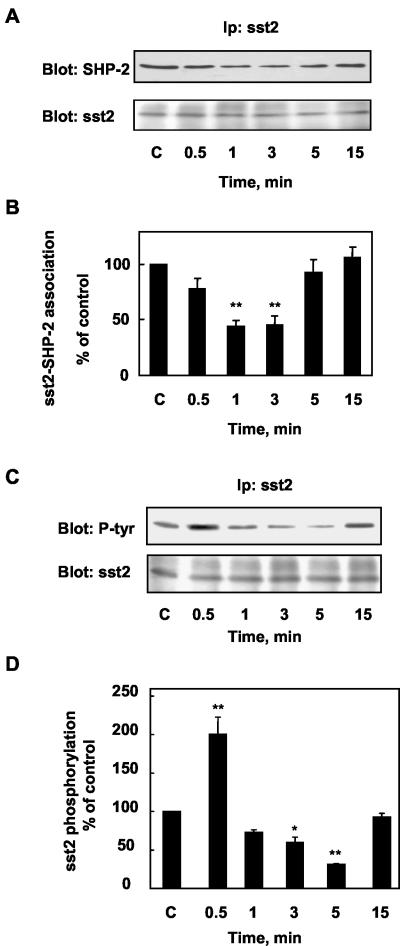

RC-160 Promotes Dissociation of SHP-2–sst2 Complexes and Regulates sst2 Tyrosine Phosphorylation

To investigate the role of somatostatin on SHP-2–sst2 complexes, we determined whether SHP-2 interaction with sst2 was affected by RC-160 treatment. CHO/sst2 cells were treated with RC-160 for various times. Cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with an anti-sst2 antibody and the amount of SHP-2 associated with sst2 was analyzed by immunoblotting with an anti-SHP-2 antibody. As observed in Figure 5, A and B, RC-160 treatment resulted in a transient decrease of the amount of SHP-2 immunoprecipitated with the anti-sst2 antibody, which was significant at 1–3 min of treatment. Thereafter, SHP-2-sst2 interaction returned to basal levels after 15 min of RC-160 treatment.

Figure 5.

sst2–SHP-2 association and sst2 tyrosine phosphorylation after RC-160 treatment of CHO/sst2 cells. (A and C) CHO/sst2 cells were incubated with 1 nM RC-160 for the indicated times and immunoprecipitated with anti-sst2 antibodies. Sst2 immunoprecipitates were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and sequentially immunoblotted with anti-SHP-2 and anti-sst2 antibodies (A) or anti-phosphotyrosine and anti-sst2 antibodies (C). (B and D) Immunoblots were densitometrically analyzed for sst2-SHP-2 association (B) and for sst2 phosphorylation (D). The data are normalized to sst2 levels and expressed as percentage of control values obtained from cells at time 0 (c). Data represent the mean ± SE of five to six independent experiments.

Because SHP-2 interacts with tyrosine phosphorylated molecules via its SH2 domains, we then explored the role of somatostatin on sst2 tyrosine phosphorylation. CHO/sst2 cells were treated with RC-160 and then immunoprecipitated with an anti-sst2 antibody. The immunoprecipitates were analyzed by Western blotting with either an anti-phosphotyrosine or an anti-sst2 antibody (Figure 5, C and D). RC-160 treatment induced a rapid and transient increase of sst2 tyrosine phosphorylation within the first 30 s (206 ± 29% of basal state) after which sst2 tyrosine phosphorylation was decreased, sst2 tyrosine dephosphorylation being minimal at 5 min and then subsequently returning to basal level at 15 min. From these results, we conclude that SHP-2 associates with tyrosine-phosphorylated sst2, in resting cells. The transient hyperphosphorylation of sst2 upon RC-160 binding is not accompanied by an increase in sst2 associated with SHP-2. However, the subsequent tyrosine dephosphorylation of sst2 is concomitant with the dissociation of preformed sst2–SHP-2 complexes.

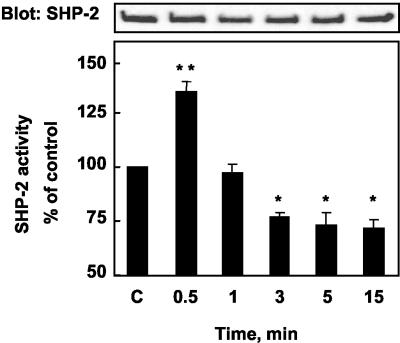

SHP-2 Activity Is Involved in RC-160–induced sst2 Tyrosine Phosphorylation Modulation, SHP-1 Activation, and Inhibitory Growth Signal

We then tested whether sst2 modulates SHP-2 catalytic activity. CHO/sst2 cells were treated with RC-160, and lysates from control and RC-160-treated cells were immunoprecipitated with an anti-SHP-2 antibody and subjected to either immune complex tyrosine phosphatase assay or immunoblot by using an anti-SHP-2 antibody. As shown in Figure 6, RC-160 induced a rapid and transient increase of SHP-2 activity within 30 s (35 ± 3.4%, p < 0.01), followed by a progressive decrease reaching 70% of the control value by 3–15 min. The demonstration that somatostatin activates SHP-2 suggests that SHP-2 might function in sst2 signaling. To examine this possibility, we generated a mutated SHP-2 cDNA, in which the active cysteine in position 459 was mutated to serine. This mutation results in a catalytically inactive enzyme (Rivard et al., 1995). We stably cotransfected cDNA encoding for both wild-type sst2 and mutated SHP-2 in CHO cells [CHO/sst2-SHP-2(C/S)] and selected, by binding analysis, clones that expressed sst2 at levels similar to those observed in CHO/sst2 cells. Correct overexpression of mutated SHP-2 in CHO/sst2-SHP-2(C/S) was also checked by Western blotting (Figure 7A). CHO/sst2-SHP-2(C/S) cells were treated with RC-160, and sst2 was immunoprecipitated with an anti-sst2 antibody and sequentially immunoblotted with an anti-phosphotyrosine and an anti-sst2 antibody. Immunoblots revealed that in cells expressing the SHP-2 mutant, tyrosine phosphorylation of sst2 was elevated when compared with control cells (our unpublished data) and sst2 tyrosine phosphorylation was not affected for any time of RC-160 treatment (Figure 7, B and C).

Figure 6.

Time course of SHP-2 activity in response to RC-160 treatment of CHO/sst2 cells. CHO/sst2 cells were incubated with 1 nM RC-160 for the indicated times before solubilization and immunoprecipitation with anti-SHP-2 antibodies. Immunoprecipitates were immunoblotted for the presence of SHP-2 (top) and assayed for tyrosine phosphatase activity (bottom). Results are expressed as percentage of phosphatase activity obtained from cells at time 0. Data represent the mean ± SE of five independent experiments performed in duplicate. Basal SHP-2 activity of control cells, 9 ± 1.3 U.

Figure 7.

Expression of catalytically inactive SHP-2 suppresses RC-160–induced sst2 tyrosine phosphorylation, SHP-1 activation, and cell growth inhibition. (A) Cell lysates from wild-type CHO (wt), CHO/sst2, or CHO/sst2-SHP-2(C/S) stable transfectants were analyzed by Western blotting with anti-SHP-2 and anti-sst2 antibodies. (B and C) CHO/sst2-SHP-2(C/S) cells were incubated with 1 nM RC-160 for the indicated times. (B) Sst2 immunoprecipitates were analyzed by immunoblotting with anti-phosphotyrosine or anti-sst2 antibodies. (C) Densitometric analysis of sst2 phosphorylation performed in B. Data are normalized to sst2 levels and expressed as percentage of control values obtained from cells at time 0 (means ± SE of three independent experiments). (D) Cells were treated for 20 min without (open bars) or with 1 nM RC-160 (closed bars). SHP-1 immunoprecipitates were immunoblotted for the presence of SHP-1 (top) and assayed for SHP-1 phosphatase activity (bottom). Data are expressed as percentage of phosphatase activity obtained from cells at time 0 and represent the mean ± SE of six independent experiments made in duplicate. (E) Cells were treated for 24 h in the presence of FCS without (open bars) or with 1 nM RC-160 (closed bars), and cell proliferation was quantified. Data are expressed as percentage of control values obtained from untreated cells and represent the mean ± SE of five independent experiments made in triplicate.

To examine whether SHP-2 catalytic activity is involved in RC-160–induced SHP-1 stimulation, CHO/sst2-SHP-2(C/S) cells were incubated with RC-160, and lysates were immunoprecipitated with an anti-SHP-1 antibody and subjected to either immune complex tyrosine phosphatase assay or immunoblot by using an anti-SHP-1 antibody. In cells expressing the SHP-2 mutant, RC-160 was inefficient for SHP-1 activation compared in CHO/sst2 cells (Figure 7D).

We then tested RC-160 effect on CHO/sst2-SHP-2(C/S) cell proliferation. When CHO/sst2 cells were incubated for 24 h with FCS in the presence of 1 nM RC-160, cell growth was inhibited by 43%. In contrast, RC-160–induced inhibition of cell growth was abolished in CHO/sst2-SHP-2(C/S) cells (Figure 7E). All these results demonstrate that expression of the catalytically inactive SHP-2 abrogates somatostatin analog-induced sst2 tyrosine phosphorylation regulation, SHP-1 activation, and cell growth inhibition.

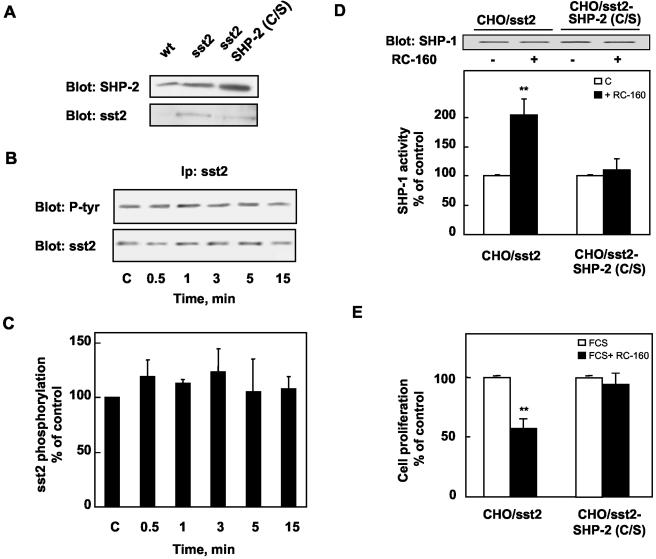

Src Associates with sst2 and RC-160 Promotes Dissociation of sst2–Src Complexes

We found that sst2 is tyrosine phosphorylated at basal level and that RC-160 induces a rapid and transient increase of sst2 tyrosine phosphorylation. These results raise the possibility that tyrosine kinases might catalyze sst2 tyrosine phosphorylation and play a role in sst2 complex regulation. Increasing evidence suggests that GPCR signals engage tyrosine kinases, including nonreceptor tyrosine kinases such as Src family kinases (Dikic et al., 1996; Luttrell et al., 1999b; Cao et al., 2000; Ma et al., 2000). Src has been involved in sst1 somatostatin receptor-induced cell growth inhibition (Florio et al., 1994). In addition, Src family tyrosine kinases have been implicated in the recruitment and activation of SHP-2 by SHP-2 binding proteins such as PECAM-1, SHPS-1, and α2A-adrenergic and lysophosphatidic Gi protein-coupled receptors (Oh et al., 1999; Tang et al., 1999; Newman et al., 2001). To test whether Src-like kinase was present in sst2 complex, CHO/sst2 cell lysates were subjected to sst2 immunoprecipitation and immunoprecipitates were assessed for Src kinase by using specific kinase (Src, Fyn, Lyn, or Yes) antibodies. In whole cell extracts, only Src was identified, the other Src-like kinases Fyn, Lyn, and Yes being not detected. In addition, Src was shown to coimmunoprecipitate with sst2 at the basal state (Figure 8A). We then tested whether somatostatin analog treatment modulates sst2–Src association in CHO/sst2 cells. Cells were treated for various times with RC-160. Cell lysates were then immunoprecipitated with an anti-sst2 antibody, and immunoprecipitates were immunoblotted with an anti-Src antibody. RC-160 treatment resulted in a dissociation of the sst2–Src complexes at 1–5 min of treatment (Figure 8, B and C). Thereafter, Src reassociated with sst2 at 15 min.

Figure 8.

Association of Src with sst2 in CHO/sst2 cells. (A) Identification of a src-related kinase that coimmunoprecipitates with sst2. Sst2 immunoprecipitates prepared from CHO/sst2 cells (+) and CHO/sst2 cell or platelet lysates (–) were assayed for src-related immunoreactivity with anti-Fyn–, anti-Lyn–, or anti-Src–specific antibodies. (B and C) CHO/sst2 cells were incubated for the indicated times with 1 nM RC-160 and immunoprecipitated with anti-sst2 antibodies. (B) Sst2 immunoprecipitates were immunoblotted with anti-Src or anti-sst2 antibodies. (C) Immunoblots were densitometrically analyzed and the data are normalized to levels of sst2 and expressed as percentage of control values obtained from cells at time 0. Data represent the mean ± SE of six independent experiments. (D) CHO-transfected cells with wild-type sst2 (wt) or Y228/312F mutant were solubilized and subjected to immunoprecipitation with anti-sst2 antibodies. Immunoprecipitates were immunoblotted with anti-Src or anti-sst2 antibodies. Immunoblots are representative of three separate experiments.

We found that sst2 tyrosine phosphorylation at Y228 and Y312 created SH2-binding domains. We evaluated the possible involvement of both tyrosine residues in sst2–Src interaction. Lysates from CHO cells expressing wild-type sst2 and Y228/312F mutant were immunoprecipitated with an anti-sst2 antibody and immunoblotted with an anti-Src antibody. As observed in Figure 8D, mutation of Y228 and Y312 did not reduce the amount of Src detected, suggesting that these residues were not required for sst2–Src association. These results were confirmed in vitro by surface plasmon resonance analysis, no interaction between Src SH2 domain and sst2 ITIM-pY228 and ITIM-pY312 sequences being observed (our unpublished data).

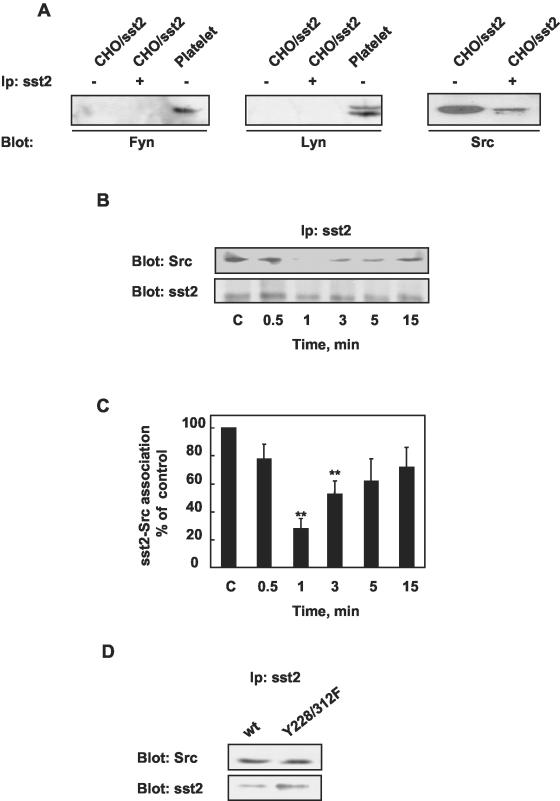

Src Is Activated by RC-160 via a Pertussis Toxin- and βγ-Sensitive Pathway

To test whether somatostatin modulates Src activity, CHO/sst2 cells were treated with RC-160, and cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with anti-Src antibodies. The immunoprecipitable Src kinase activity was determined by its ability to phosphorylate Src kinase-specific substrate, enolase. Src was active at basal level and RC-160 treatment resulted in a biphasic increase of Src kinase activity. Src activity was increased by threefold as early as 30 s of treatment, returned to basal level by 1–3 min and then, slightly increased at 5–15 min (Figure 9, A and B).

Figure 9.

RC-160 treatment induces Src activation by a SHP-2–independent but Gβγ-dependent mechanism. (A) CHO/sst2 cells were incubated for the indicated times with 1 nM RC-160 and immunoprecipitated with anti-Src antibody. Src immunoprecipitates were assayed for Src activity by using enolase as a substrate. The same immunoprecipitates were immunoblotted with anti-Src antibody (B, top). (B, bottom) Radioblots presented in A were densitometrically analyzed, and the data are normalized to levels of Src and expressed as percentage of control values obtained from cells at time 0. Data represent the mean ± SE of four independent experiments. (C) Role of SHP-2 activity on Src activity. CHO/sst2 and CHO/sst2/SHP-2(C/S) cells were treated with 1 nM RC-160 and subjected to Src kinase activity. (D) Top, Src immunoprecipitates from CHO/sst2/SHP-2(C/S) cells were immunoblotted with anti-Src antibody. Bottom, densitometric analysis of Src activity in CHO/sst2/SHP-2(C/S) cells presented in C. Data are expressed as percentage of control values obtained from cells at time 0 and represent the mean ± SE of three independent experiments. (E) Pertussis toxin effect on Src activity. After a 16-h pretreatment with pertussis toxin at 100 ng/ml, CHO/sst2 cells were treated with 1 nM RC-160 and subjected to Src kinase activity. (F) Role of Gβγ subunit on Src activity. CHO/sst2 cells were transiently transfected with βARK1-CT construct and treated with 1 nM RC-160. Src Immunoprecipitates were assayed for Src activity. Autoradiographs are representative of three (E and F) separate experiments.

As other Src family tyrosine kinases, Src is negatively regulated by two intramolecular interactions involving binding of the SH2 domain to the phosphorylated C-terminal tail and association of the SH3 domain with a polyproline type II helix formed by the SH2-kinase linker. Several tyrosine phosphatases have been implicated in Src regulation (for review, see Bjorge et al., 2000). To determine whether SHP-2 plays a role in Src regulation, we measured basal and RC-160–activated Src kinase activity in CHO/sst2 and CHO/sst2-SHP-2(C/S) cells. CHO/sst2-SHP-2(C/S) cells exhibited elevated Src activity compared with CHO/sst2 cells (Figure 9C). These results are in agreement with previous studies showing that overexpression of wild-type or catalytically inactive SHP-2 results in Src activation, SHP-2 controlling Src activity by a nonenzymatic mechanism through interaction with its SH3 domain (Walter et al., 1999). In addition, RC-160 activated Src in CHO/sst2-SHP-2(C/S) cells, suggesting that SHP-2 activity is not involved in RC-160–induced Src activation (Figure 9, C and D).

Sst2 has been demonstrated to be coupled to pertussis toxin-sensitive Gi protein (Lopez et al., 1997; Meyerhof, 1998). To test whether Gi protein is involved in somatostatin analog-induced Src activation, we next examined the effect of cell pertussis toxin pretreatment on somatostatin-mediated Src activation. CHO/sst2 cells were pretreated with pertussis toxin for 16 h and then treated with RC-160. As shown in Figure 9E, RC-160–induced early increase of Src activity was completely suppressed by pertussis toxin pretreatment, suggesting that a pertussis toxin-sensitive Gi protein is involved in RC-160–induced Src activation. It is now well demonstrated that Gi-mediated signals can be carried by the Gβγ subunits, which lead to the activation of Src (or related tyrosine kinases) and subsequent tyrosine phosphorylation of several adaptor or scaffold proteins (Lefkowitz, 1998). The β-adrenergic receptor kinases (βARK) translocate to a variety of GPCRs by forming a complex with the Gβγ released upon activation of heterotrimeric G proteins. The specific region of βARK that directly interacts with and binds Gβγ is located within the carboxyl 125-amino acid residue stretch. Expression of this domain, βARK1 construct (βARK1-CT), has been shown to act as a specific Gβγ sequestrant molecule (Koch et al., 1994). To investigate whether Gβγ participates in RC-160–induced Src activation, cells were transiently transfected with βARK1-CT and we measured RC-160–mediated Src activation. As shown in Figure 9F, βARK1-CT abrogated somatostatin-induced Src activation. These results indicate that Gi-derived βγ played an essential role in somatostatin analog-induced Src activation.

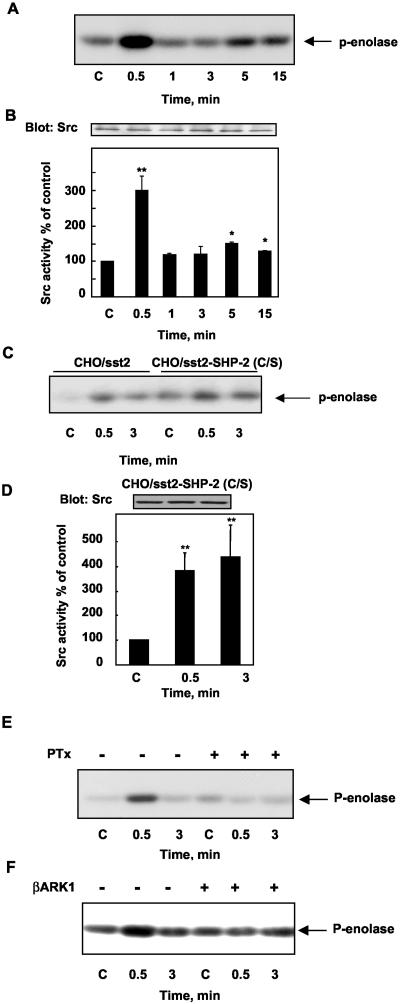

Role of Src Activity in sst2 Complex Regulation

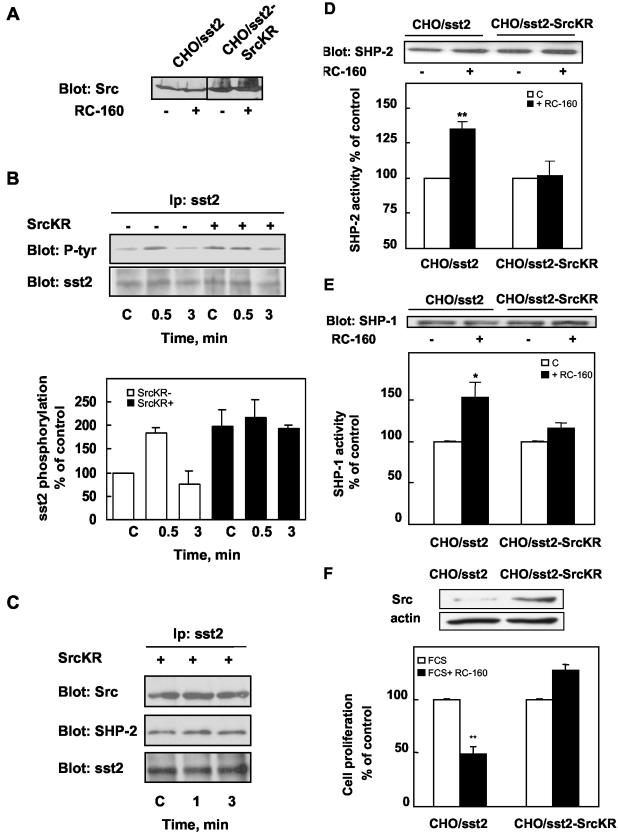

To examine the role of Src in sst2 complex regulation, we transiently expressed a Src catalytically inactive form (Src K295R) in CHO/sst2 cells. Correct overexpression of this mutant was checked by Western blotting with anti-Src antibody (Figure 10A). We first analyzed the role of Src on RC-160–mediated sst2 tyrosine phosphorylation. After RC-160 treatment, cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with anti-sst2 antibodies, and the immune complexes were analyzed by SDS-PAGE followed by Western blotting with anti-phosphotyrosine antibodies. As observed in Figure 10B, in control cells, we confirmed that RC-160 transiently enhanced sst2 tyrosine phosphorylation at 30 s of treatment. In contrast, in cells expressing Src K295R, basal sst2 tyrosine phosphorylation was increased compared with control cells and RC-160 was unable to regulate sst2 tyrosine phosphorylation. These data did not argue for a positive role for Src in the regulation of basal sst2 phosphorylation level but suggest that Src plays a role in both RC-160–induced sst2 hypertyrosine phosphorylation and dephosphorylation. We next examined whether Src activity can participate in somatostatin-mediated regulation of sst2–Src–SHP-2 complexes. Expression of a Src catalytically inactive form did not affect the formation of sst2–Src–SHP–2 complexes in unstimulated cells but abolished RC-160–induced dissociation of sst2–Src–SHP-2 complexes (Figure 10C). These results suggest that Src activity is required for sst2–Src–SHP-2 complex dissociation and confirm the relation between sst2 dephosphorylation and sst2–Src–SHP-2 complex dissociation. We then investigated whether Src activity is required for RC-160–induced SHP-2 and SHP-1 activation. As shown in Figure 10, D and E, expression of Src K295R in CHO/sst2 cells abolished RC-160–induced increase of SHP-2 and SHP-1 activities, compared with control cells. Finally, we explored the role of Src in RC-160–mediated inhibition of cell proliferation. As shown in Figure 10F, expression of inactive Src abrogated RC-160 inhibitory effect on CHO/sst2 cell proliferation. Together, these results demonstrate that introduction of a Src catalytically inactive form does not modify the formation of sst2–Src–SHP-2 complexes but abolishes all first steps of sst2-induced cell growth inhibition signaling and provide evidence that Src is an upstream regulator of SHP-2.

Figure 10.

Effects of a dominant negative Src on somatostatin signaling. (A) CHO/sst2 cells were transiently transfected with the catalytically inactive Src mutant [Src(K295R)] (CHO/sst2-SrcKR). Cell lysates were examined for Src protein expression by Western blotting by using Src antibodies. (B) CHO/sst2 (–) and CHO/sst2-SrcKR (+) cells were incubated for the indicated times with 1 nM RC-160 and immunoprecipitated with anti-sst2 antibodies. Top, sst2 immunoprecipitates were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted with anti-phosphotyrosine or anti-sst2 antibodies. Bottom, densitometric analysis of sst2 tyrosine phosphorylation. Data represent the mean ± SE of three experiments and are expressed as percentage of control values obtained from cells at time 0. (C) CHO/sst2-SrcKR cells were incubated for the indicated times with 1 nM RC-160 and immunoprecipitated with anti-sst2 antibodies. Sst2 immunoprecipitates were immunoblotted with anti-Src, anti-SHP-2 or anti-sst2 antibodies. Immunoblots are representative of three separate experiments. (D and E) CHO/sst2 and CHO/sst2-SrcKR cells were treated for 30 s (D) or 20 min (E) without (open bars) or with 1 nM RC-160 (closed bars). Cells lysates were subjected to immunoprecipitation with anti-SHP-2 (D) or anti-SHP-1 (E) antibodies. Immunoprecipitates were assayed for SHP-2 (D) or SHP-1 (E) phosphatase activity. The same immunoprecipitates were subjected to SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting with anti-SHP-2 (D, top) or anti-SHP-1 (E, top) antibodies. Results are expressed as percentage of phosphatase activity obtained from cells at time 0 and represent the mean ± SE of six independent experiments made in duplicate. (F) CHO/sst2 and CHO/sst2-SrcKR cells were treated for 24 h in the presence of FCS without (open bars, bottom) or with 1 nM RC-160 (closed bars, bottom). Cell lysates were examined for Src protein expression by Western blotting and β actin was used as an internal loading control (top). Results are expressed as percentage of cell proliferation obtained from untreated control cells (bottom). Data represent the mean ± SE of four independent experiments made in triplicate.

DISCUSSION

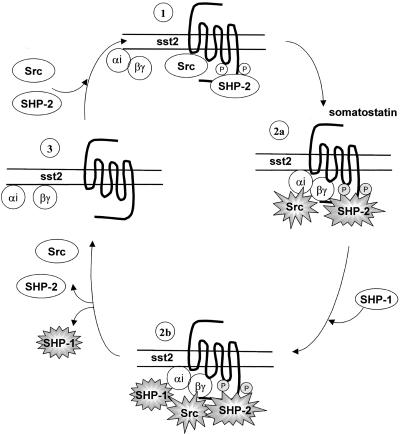

The G protein-coupled sst2 receptor acts as a negative regulator of growth factor-induced mitogenic signals whose action depends on the tyrosine phosphatase SHP-1 (Buscail et al., 1995; Lopez et al., 1997; Bousquet et al., 1998). In the present study, we describe a novel mechanism for SHP-1 activation involving the tyrosine phosphatase SHP-2 and the tyrosine kinase Src. 1) We identified ITIMs within the third intracellular loop and C-terminal part of sst2. We demonstrated that SHP-2 constitutively associates via its SH2 domains with phosphorylated tyrosine residues 228 and 312 containing sst2 ITIMs. 2) We found that sst2–SHP-2 interaction is required for transmitting sst2-dependent signal transduction leading to SHP-1 activation and consequent cell growth arrest. 3) We showed that Src forms a multicomplex with sst2 and SHP-2 and that somatostatin analog RC-160 induces transient Gi protein βγ-dependent Src activation that leads to concomitant enhanced sst2 tyrosine phosphorylation and SHP-2 activation. 4) We presented evidence that the sequential activation of Src and SHP-2 is required for sst2-mediated SHP-1 activation and cell growth inhibition. These results provide a new mechanism for GPCR-mediated inhibitory signaling (Figure 11).

Figure 11.

Schematic representation of sst2-induced reversible transduction pathway. 1) Basal state, Src tyrosine kinase and SHP-2 tyrosine phosphatase are both associated with tyrosine phosphorylated sst2. 2) Somatostatin-activated state at 30s (a), upon somatostatin-induced sst2 activation, Src becomes activated by a Gβγ-dependent mechanism. Src activation is associated with sst2 hyperphosphorylation and SHP-2 activation; (b) dephosphorylation of signal relay molecules permits SHP-1 recruitment and activation. 3) Somatostatin activated state at 1–15 min, Sst2 is dephosphorylated. All proteins dissociate, and activated SHP-1 mediates sst2 inhibitory effects by dephosphorylating its substrates. At 15 min, Src and SHP-2 are recruited back to the complex.

In mammalian cells, the SH2 domain-containing tyrosine phosphatase family, which includes SHP-1 and SHP-2, shares a general structure, including two SH2 domains at the N terminus followed by a catalytic domain and a C-terminal region containing two putative sites of tyrosine phosphorylation. These phosphatases are recruited via their SH2 domains by specific phosphotyrosine sites within ITIM consensus sequence (S/I/L/VxYxxL/V/I) (for review, see Long, 1999; Blery et al., 2000). We identified two ITIMs in the sst2 sequence (LCY228LFI and ILY312AFL) that fulfill requirements for SH2-containing phosphatase binding. Using surface plasmon resonance, we demonstrated a direct and specific interaction between both tyrosine phosphorylated sst2 ITIMs and SHP-2 SH2 domains. Each tyrosine-phosphorylated ITIM is able alone to interact with SHP-2 SH2 domains with nearly identical high nanomolar affinity, similar to that reported for SHP-2 binding to ITIM-bearing molecules NKG2A (Le Drean et al., 1998) and PECAM-1 (Hua et al., 1998). Other members of the somatostatin receptor family share a high sequence homology with sst2 ITIM motifs, suggesting a direct association of SHP-2 with these receptors. Surface plasmon resonance studies have demonstrated binding of most reported phosphorylated ITIMs to both SHP-1 and SHP-2 (Vely et al., 1997; Blery et al., 1998; Hua et al., 1998). However, recent studies have shown that ITIM-bearing receptors can specifically recruit either SHP-1 or SHP-2 (Xu et al., 2000; Okazaki et al., 2001; Daigle et al., 2002; Duchene et al., 2002; Zhao et al., 2002). We found that SHP-1 fails to interact, in vitro and in vivo, with sst2 ITIMs, suggesting that additional residues other than residues at the Y-2 and Y+3 positions of the ITIM consensus sequence may be important for binding specificity of SHP-2 SH2 domains to sst2 phosphorylated ITIMs (Huber et al., 1999).

Our results also indicate that sst2 interaction with SHP-2 does exist in vivo. Analysis of cells expressing sst2 mutated in Phe at both Y228 and Y312 show that both phosphorylated tyrosine residues are required for SHP-2 binding, suggesting that both sst2 ITIMs are critical for their association with both SHP-2 SH2 domains. Moreover, we demonstrated that the formation of sst2–SHP-2 complexes is required for sst2 signaling, including SHP-1 activation and cell growth inhibition. In this context, we recently reported that SHP-2 associates via its SH2 domains with the tyrosine phosphorylated ITIM sequence of another inhibitory GPCR, the bradykinin B2 receptor, and this interaction is necessary to transduce B2 receptor-mediated antimitogenic signal (Duchene et al., 2002). Together, these data suggest that these two GPCR, sst2 and B2 receptors, are members of the ITIM-bearing receptor family and that direct interaction of these receptors with SHP-2 is required for ligand induction of cell proliferation inhibition.

Despite our surface plasmon resonance analysis that indicates that both sst2 tyrosine residues bind SHP-2 SH2 domains with the same high affinity, our coimmunoprecipitation data reveal that Y228 is more efficient than Y312 for SHP-2 recruitment, in vivo. Because ITIMs tyrosine phosphorylation is a prerequisite event leading to SHP-2 binding, it is likely that Y228 and Y312 residues are constitutively tyrosine phosphorylated in unstimulated cells, allowing sst2–SHP-2 complex formation. Analysis of tyrosine phosphorylation level of sst2 mutants is consistent with this hypothesis because mutation of either Y228 or Y312 results in a decrease of sst2 tyrosine phosphorylation level. However, the observation that mutation of Y228 suppresses sst2 phosphorylation level by >70% and sst2–SHP-2 interaction by 86% suggests that in the basal state, sst2 is preferentially tyrosine phosphorylated at Y228 and that Y228-containing sst2 ITIM is the major site for sst2-SHP-2 interaction, in vivo.

GPCRs have no intrinsic tyrosine kinase activity, and recruitment and activation of Src family kinases are now known to play a role in GPCR-mediated Ras-dependent activation of mitogenic signaling pathways (Luttrell and Lefkowitz, 2002). Src activity is also involved in sst1 somatostatin receptor- and AMPc-mediated antiproliferative effects (Florio et al., 1999; Schmitt and Stork, 2001). The data presented herein clearly demonstrate that Src specifically interacts with sst2–SHP-2 complexes and that somatostatin analog RC-160 transiently activates Src. Several mechanisms have been shown to mediate Src activation by GPCRs. Src is activated by either dephosphorylation of its C-terminal regulatory tyrosine, or engagement of the SH2 and SH3 domains with heterologous proteins (Cao et al., 2000; Ma et al., 2000; Schlessinger, 2000). GPCR-induced Src activation can also occur through direct binding of Src to β-arrestin by a βγ-dependent mechanism (for review, see Luttrell and Lefkowitz, 2002). Recently, β-arrestin has been shown to be recruited by activated sst2 receptors (Mundell and Benovic, 2000; Brasselet et al., 2002). We found that RC-160–activated sst2 stimulates Src by a Gi protein βγ-dependent mechanism. Thus, one possibility is that, in sst2 signaling, somatostatin-mediated βγ-dependent recruited β-arrestin participates in Src activation. However, we cannot exclude the involvement of another mechanism in somatostatin-mediated Src activation.

Src activation occurs concomitantly with sst2 hypertyrosine phosphorylation, SHP-2 and SHP-1 activation. The finding that loss of Src activity abrogates all these effects suggests that activation of Src may initiate a signaling cascade leading to sst2 tyrosine hyperphosphorylation and subsequent SHP-2 activation. However, the observation that Src mutant leads to increased basal sst2 tyrosine phosphorylation raises the possibility that a further increase in sst2 tyrosine phosphorylation in response to somatostatin analog would not be identifiable. We believe that somatostatin-mediated hyperphosphorylation of sst2 plays a role in SHP-2 activation by providing SH2-binding sites for SHP-2. Structural and enzymatic studies of SHP-2 have shown the role of SHP-2 N-terminal SH2 domain for binding to tyrosine phosphorylated peptides as a way for SHP-2 activation (Barford and Neel, 1998; Hof et al., 1998). Furthermore, engagement of both SH2 domains, rather than only one SH2 domain, is more efficient for SHP-2 activation (Pluskey et al., 1995). Our present findings raise the possibility that both SHP-2 SH2 domains may be differentially recruited in unstimulated and stimulated cells. Hypertyrosine phosphorylation of sst2 may occur at ITIMs, and poorly phosphorylated ITIMs in unstimulated cells may become phosphorylated after sst2 activation and bind SHP-2 SH2 domains. Hypertyrosine phosphorylation of sst2 may occur at additional sites on sst2 that could serve as SHP-2 binding sites directly or indirectly through recruitment and tyrosine phosphorylation of another molecule in the sst2 multicomplex.

The interaction of sst2 with Src and SHP-2 is dynamic, and our data showed that somatostatin analog RC-160 induces a rapid dissociation of sst2–Src–SHP-2 complexes concomitant with a decrease of Src and SHP-2 activities, and sst2 dephosphorylation. The finding that loss of SHP-2 catalytic activity abrogates sst2 tyrosine dephosphorylation in response to somatostatin suggests that this effect is subsequent to SHP-2 activation. Such an effect was not observed with catalytically inactive SHP-1 (our unpublished data). Because SHP-2 is known to dephosphorylate its associated ITIM-bearing molecules (Zhao and Zhao, 2000; Cunnick et al., 2001), it is possible that SHP-2 dephosphorylates (directly or indirectly) sst2 in response to somatostatin, thereby inducing sst2–SHP-2 complex dissociation and SHP-2 inhibition. Further studies will be required to address these issues. It is noteworthy that somatostatin-mediated dissociation of the preformed sst2–Src–SHP-2 complexes is transient and followed by Src and SHP-2 reassociation with sst2 within 5 min after somatostatin treatment, when sst2 is maximally dephosphorylated. Theses results suggest that SHP-2 may be recruited directly or indirectly to the receptor by a mechanism independently of sst2 phosphorylated tyrosine residues. Indeed, SHP-2 can interact with its substrates independently of its SH2 domains (Walter et al., 1999; Tang et al., 2000).

The signaling mechanism for SHP-2 involvement in sst2-mediated SHP-1 stimulation remains to be determined. However, our data are in agreement with previous reports indicating that in NIH 3T3 cells transiently expressing sst2, coexpression with catalytically inactive SHP-2 abrogates a somatostatin-induced tyrosine phosphatase activation (Reardon et al., 1997). Identification of sst2-binding protein(s) whose tyrosine phosphorylation is down-regulated by SHP-2 is therefore of critical interest. GPCRs have been shown to recruit and activate several Src family kinases (Luttrell et al., 1999a; Tang et al., 2000; Ptasznik et al., 2002). One possibility is that activated sst2 recruits an additional src family kinase, which is dephosphorylated (at inhibitory C-terminal phosphotyrosyl residues) and activated by SHP-2. Activated tyrosine kinase then can phosphorylate additional site in sst2 or another protein, which allows SHP-1 recruitment and activation. Another possibility is that activation of sst2 leads to the interaction of sst2 with another yet unidentified protein or the conformational change of the receptor, which may account for recruiting SHP-1. GPCRs have recently been shown to be involved in protein–protein interactions with scaffold proteins containing PSD-95/Discs-large/ZO-1 (PDZ), SH2 (src homology), or SH3 domains (Bockaert and Pin, 1999). These proteins play a role in the scaffolding and targeting of proteins to specific subcellular domains and help organize signal transduction machinery in the receptor vicinity. PSD-95, a PDZ domain protein, is involved in the clustering of N-methyl-d-aspartate receptor and the cytosolic enzymes Src and PTPα or β1-adrenergic receptor (Hu et al., 2000; Lei et al., 2002). Another scaffolding adapter, Gab1, acts in concert with SHP-2 to control the kinetics, extent, and location of phosphatidylinositol 3′-kinase activation in response to epidermal growth factor (Zhang et al., 2002). Somatostatin receptor interacting protein 1 and cortactin-binding protein 1 have been identified as binding partner for sst2 (Zitzer et al., 1999a,b). These identified and as yet unidentified sst2-interacting proteins will provide insight into the mechanisms that are involved in SHP-1 recruitment to the sst2 receptor complex and SHP-1 activation.

Our study demonstrated that the tyrosine phosphatases SHP-1 and SHP-2 have not a redundant function in transducing sst2 signal. Src and SHP-2 act as upstream regulators of SHP-1 to deliver negative growth signal initiated by a GPCR. Sst2 signal regulation is a dynamic process that is dependent on complex succession of protein–protein interactions and protein activation and supports the inclusion of sst2 within the family of ITIM-bearing inhibitory receptors.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to S. Roche, P. Cordelier (INSERM U531, Toulouse, France), and R.J. Lefkowitz for providing Src, green fluorescent protein, and βARK1-CT constructs, respectively; C. Nahmias and N. Rivard (University of Sherbrooke, Quebec, Canada) for providing SHP-2 construct; and G.I. Bell and T. Reisine for providing CHO cells expressing sst2A receptors. We thank P. Merkel and M. Zatelli (Cedars Sinai Medical Center, UCLA, Los Angeles, CA) for constructive criticisms of the manuscript. We also thank C. Bousquet, S. Pyronnet, C. Seva, and A. Kowalski-Chauvel (INSERM U531, Toulouse, France) for helpful discussions. This work was supported by grants from Association pour la Recherche contre le Cancer (ARE-CA), Conseil Régional Midi-Pyrénées (2ACFH0113C), Ligue Nationale contre le Cancer (2578DB06D), and EC contract QLG3-CT-1999-00908. G.F. is supported by doctoral fellowship from Association pour la Recherche contre le Cancer.

Article published online ahead of print. Mol. Biol. Cell 10.1091/mbc.E03–02–0069. Article and publication date are available at www.molbiolcell.org/cgi/doi/10.1091/mbc.E03-02-0069.

References

- Ali, S. (2000). Recruitment of the protein-tyrosine phosphatase SHP-2 to the C-terminal tyrosine of the prolactin receptor and to the adaptor protein Gab2. J. Biol. Chem. 275, 39073–39080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barford, D., and Neel, B.G. (1998). Revealing mechanisms for SH2 domain mediated regulation of the protein tyrosine phosphatase SHP-2. Structure 6, 249–254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benali, N., et al. (2000). Inhibition of growth and metastatic progression of pancreatic carcinoma in hamster after somatostatin receptor subtype 2 (sst2) gene expression and administration of cytotoxic somatostatin analog AN-238. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97, 9180–9185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bjorge, J.D., Jakymiw, A., and Fujita, D.J. (2000). Selected glimpses into the activation and function of Src kinase. Oncogene 19, 5620–5635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blery, M., Kubagawa, H., Chen, C.C., Vely, F., Cooper, M.D., and Vivier, E. (1998). The paired Ig-like receptor PIR-B is an inhibitory receptor that recruits the protein-tyrosine phosphatase SHP-1. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95, 2446–2451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blery, M., Olcese, L., and Vivier, E. (2000). Early signaling via inhibitory and activating NK receptors. Hum. Immunol. 61, 51–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bockaert, J., and Pin, J.P. (1999). Molecular tinkering of G protein-coupled receptors: an evolutionary success. EMBO J. 18, 1723–1729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bousquet, C., Delesque, N., Lopez, F., Saint-Laurent, N., Esteve, J.P., Bedecs, K., Buscail, L., Vaysse, N., and Susini, C. (1998). sst2 somatostatin receptor mediates negative regulation of insulin receptor signaling through the tyrosine phosphatase Shp-1. J. Biol. Chem. 273, 7099–7106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brasselet, S., Guillen, S., Vincent, J.P., and Mazella, J. (2002). Beta-arrestin is involved in the desensitization but not in the internalization of the somatostatin receptor 2A expressed in CHO cells. FEBS Lett 516, 124–128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buscail, L., et al. (1994). Stimulation of tyrosine phosphatase and inhibition of cell proliferation by somatostatin analogues: mediation by human somatostatin receptor subtypes SSTR1 and SSTR2. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 91, 2315–2319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buscail, L., et al. (1995). Inhibition of cell proliferation by the somatostatin analogue RC-160 is mediated by somatostatin receptor subtypes SSTR2 and SSTR5 through different mechanisms. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 92, 1580–1584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao, W., Luttrell, L.M., Medvedev, A.V., Pierce, K.L., Daniel, K.W., Dixon, T.M., Lefkowitz, R.J., and Collins, S. (2000). Direct binding of activated c-Src to the beta 3-adrenergic receptor is required for MAP kinase activation. J. Biol. Chem. 275, 38131–38134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunnick, J.M., Mei, L., Doupnik, C.A., and Wu, J. (2001). Phosphotyrosines 627 and 659 of Gab1 constitute a bisphosphoryl tyrosine-based activation motif (BTAM) conferring binding and activation of SHP2. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 24380–24387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daigle, I., Yousefi, S., Colonna, M., Green, D.R., and Simon, H.U. (2002). Death receptors bind SHP-1 and block cytokine-induced anti-apoptotic signaling in neutrophils. Nat. Med. 8, 61–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D'Ambrosio, D., Hippen, K.L., Minskoff, S.A., Mellman, I., Pani, G., Siminovitch, K.A., and Cambier, J.C. (1995). Recruitment and activation of PTP1C in negative regulation of antigen receptor signaling by Fc gamma RIIB1 [see comments]. Science 268, 293–297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dikic, I., Tokiwa, G., Lev, S., Courtneidge, S.A., and Schlessinger, J. (1996). A role for Pyk2 and Src in linking G-protein-coupled receptors with MAP kinase activation. Nature 383, 547–550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duchene, J., Schanstra, J.P., Pecher, C., Pizard, A., Susini, C., Esteve, J.P., Bascands, J.L., and Girolami, J.P. (2002). A novel protein-protein interaction between a G protein-coupled receptor and the phosphatase SHP-2 is involved in bradykinin-induced inhibition of cell proliferation. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 40375–40383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Florio, T., Rim, C., Hershberger, R.E., Loda, M., and Stork, P.J. (1994). The somatostatin receptor SSTR1 is coupled to phosphotyrosine phosphatase activity in CHO-K1 cells. Mol. Endocrinol. 8, 1289–1297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Florio, T., Yao, H., Carey, K.D., Dillon, T.J., and Stork, P.J. (1999). Somatostatin activation of mitogen-activated protein kinase via somatostatin receptor 1 (SSTR1). Mol. Endocrinol. 13, 24–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujioka, Y., Matozaki, T., Noguchi, T., Iwamatsu, A., Yamao, T., Takahashi, N., Tsuda, M., Takada, T., and Kasuga, M. (1996). A. novel membrane glycoprotein, SHPS-1, that binds the S.H2-domain-containing protein tyrosine phosphatase SHP-2 in response to mitogens and cell adhesion. Mol. Cell. Biol. 16, 6887–6899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu, Y.Z., and Schonbrunn, A. (1997). Coupling specificity between somatostatin receptor sst2A and G proteins: isolation of the receptor-G protein complex with a receptor antibody. Mol. Endocrinol. 11, 527–537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hof, P., Pluskey, S., Dhe-Paganon, S., Eck, M.J., and Shoelson, S.E. (1998). Crystal structure of the tyrosine phosphatase SHP-2. Cell 92, 441–450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu, L.A., Tang, Y., Miller, W.E., Cong, M., Lau, A.G., Lefkowitz, R.J., and Hall, R.A. (2000). beta 1-adrenergic receptor association with PSD-95. Inhibition of receptor internalization and facilitation of beta 1-adrenergic receptor interaction with N-methyl-d-aspartate receptors. J. Biol. Chem. 275, 38659–38666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hua, C.T., Gamble, J.R., Vadas, M.A., and Jackson, D.E. (1998). Recruitment and activation of SHP-1 protein-tyrosine phosphatase by human platelet endothelial cell adhesion molecule-1 (PECAM-1). Identification of immunoreceptor tyrosine-based inhibitory motif-like binding motifs and substrates. J. Biol. Chem. 273, 28332–28340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huber, M., Izzi, L., Grondin, P., Houde, C., Kunath, T., Veillette, A., and Beauchemin, N. (1999). The carboxyl-terminal region of biliary glycoprotein controls its tyrosine phosphorylation and association with protein-tyrosine phosphatases SHP-1 and SHP-2 in epithelial cells. J. Biol. Chem. 274, 335–344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kazlauskas, A., Feng, G.S., Pawson, T., and Valius, M. (1993). The 64-kDa protein that associates with the platelet-derived growth factor receptor beta subunit via Tyr-1009 is the SH2-containing phosphotyrosine phosphatase Syp. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 90, 6939–6943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koch, W.J., Hawes, B.E., Inglese, J., Luttrell, L.M., and Lefkowitz, R.J. (1994). Cellular expression of the carboxyl terminus of a G protein-coupled receptor kinase attenuates G beta gamma-mediated signaling. J. Biol. Chem. 269, 6193–6197. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Drean, E., Vely, F., Olcese, L., Cambiaggi, A., Guia, S., Krystal, G., Gervois, N., Moretta, A., Jotereau, F., and Vivier, E. (1998).. Inhibition of antigen-induced T cell response and antibody-induced NK cell cytotoxicity by NKG2A: association of NKG2A with SHP-1 and SHP-2 protein-tyrosine phosphatases [published erratum appears in Eur. J. Immunol. 1998 Mar;28(3):1122]. Eur. J. Immunol. 28, 264–276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lefkowitz, R.J. (1998). G protein-coupled receptors. III. New roles for receptor kinases and beta-arrestins in receptor signaling and desensitization. J. Biol. Chem. 273, 18677–18680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lei, G., et al. (2002). Gain control of N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor activity by receptor-like protein tyrosine phosphatase alpha. EMBO J. 21, 2977–2989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Long, E.O. (1999). Regulation of immune responses through inhibitory receptors. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 17, 875–904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez, F., Esteve, J.P., Buscail, L., Delesque, N., Saint-Laurent, N., Theveniau, M., Nahmias, C., Vaysse, N., and Susini, C. (1997). The tyrosine phosphatase SHP-1 associates with the sst2 somatostatin receptor and is an essential component of sst2-mediated inhibitory growth signaling. J. Biol. Chem. 272, 24448–24454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez, F., Ferjoux, G., Cordelier, P., Saint-Laurent, N., Esteve, J.P., Vaysse, N., Buscail, L., and Susini, C. (2001). Neuronal nitric oxide synthase is a SHP-1 substrate involved in sst2 somatostatin receptor growth inhibitory signaling. FASEB J. 17, 17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luttrell, L.M., Daaka, Y., and Lefkowitz, R.J. (1999a). Regulation of tyrosine kinase cascades by G-protein-coupled receptors. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 11, 177–183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luttrell, L.M., et al. (1999b). Beta-arrestin-dependent formation of beta2 adrenergic receptor-Src protein kinase complexes. Science 283, 655–661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luttrell, L.M., and Lefkowitz, R.J. (2002). The role of beta-arrestins in the termination and transduction of G-protein-coupled receptor signals. J. Cell Sci. 115, 455–465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma, Y.C., Huang, J., Ali, S., Lowry, W., and Huang, X.Y. (2000). Src tyrosine kinase is a novel direct effector of G proteins. Cell 102, 635–646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marrero, M.B., Venema, V.J., Ju, H., Eaton, D.C., and Venema, R.C. (1998). Regulation of angiotensin II-induced JAK2 tyrosine phosphorylation: roles of SHP-1 and SHP-2. Am. J. Physiol. 275, C1216–C1223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyerhof, W. (1998). The elucidation of somatostatin receptor functions: a current view. Rev. Physiol. Biochem. Pharmacol. 133, 55–108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mundell, S.J., and Benovic, J.L. (2000). Selective regulation of endogenous G protein-coupled receptors by arrestins in HEK293 cells. J. Biol. Chem. 275, 12900–12908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munson, P.J., and Rodbard, D. (1980). Ligand: a versatile computerized approach for characterization of ligand-binding systems. Anal. Biochem. 107, 220–239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myers, M.G., Jr., Mendez, R., Shi, P., Pierce, J.H., Rhoads, R., and White, M.F. (1998). The COOH-terminal tyrosine phosphorylation sites on IRS-1 bind SHP-2 and negatively regulate insulin signaling. J. Biol. Chem. 273, 26908–26914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neel, B.G., and Tonks, N.K. (1997). Protein tyrosine phosphatases in signal transduction. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 9, 193–204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newman, D.K., Hamilton, C., and Newman, P.J. (2001). Inhibition of antigen-receptor signaling by platelet endothelial cell adhesion molecule-1 (CD31) requires functional ITIMs, SHP-2, and p56(lck). Blood 97, 2351–2357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oh, E.S., Gu, H., Saxton, T.M., Timms, J.F., Hausdorff, S., Frevert, E.U., Kahn, B.B., Pawson, T., Neel, B.G., and Thomas, S.M. (1999). Regulation of early events in integrin signaling by protein tyrosine phosphatase SHP-2. Mol. Cell. Biol. 19, 3205–3215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okazaki, T., Maeda, A., Nishimura, H., Kurosaki, T., and Honjo, T. (2001). PD-1 immunoreceptor inhibits B cell receptor-mediated signaling by recruiting src homology 2-domain-containing tyrosine phosphatase 2 to phosphotyrosine. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98, 13866–13871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olcese, L., et al. (1996). Human and mouse killer-cell inhibitory receptors recruit PTP1C and PTP1D protein tyrosine phosphatases. J. Immunol. 156, 4531–4534. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]