Abstract

Electrical potentials in cell walls (ψWall) and at plasma membrane surfaces (ψPM) are determinants of ion activities in these phases. The ψPM plays a demonstrated role in ion uptake and intoxication, but a comprehensive electrostatic theory of plant-ion interactions will require further understanding of ψWall. ψWall from potato (Solanum tuberosum) tubers and wheat (Triticum aestivum) roots was monitored in response to ionic changes by placing glass microelectrodes against cell surfaces. Cations reduced the negativity of ψWall with effectiveness in the order Al3+ > La3+ > H+ > Cu2+ > Ni2+ > Ca2+ > Co2+ > Cd2+ > Mg2+ > Zn2+ > hexamethonium2+ > Rb+ > K+ > Cs+ > Na+. This order resembles substantially the order of plant-root intoxicating effectiveness and indicates a role for both ion charge and size. Our measurements were combined with the few published measurements of ψWall, and all were considered in terms of a model composed of Donnan theory and ion binding. Measured and model-computed values for ψWall were in close agreement, usually, and we consider ψWall to be at least proportional to the actual Donnan potentials. ψWall and ψPM display similar trends in their responses to ionic solutes, but ions appear to bind more strongly to plasma membrane sites than to readily accessible cell wall sites. ψWall is involved in swelling and extension capabilities of the cell wall lattice and thus may play a role in pectin bonding, texture, and intercellular adhesion.

The cell wall (CW) is composed of various cross-linked units (macrofibrils, microfibrils, micelles, cellulose units, and linked agents such as neutral sugars, pectin, proteins, and ions; Cosgrove, 1997; Buchanan et al., 2000). The CW behaves as an ion exchanger where the fixed CW charges interact with exchangeable ions in the surrounding solution (Briggs and Robertson, 1957; Gillet and Lefèbvre, 1981; Sentenac and Grignon, 1981; Irwin et al., 1985; Richter and Dainty, 1989a, 1989b, 1990a, 1990b; Grignon and Sentenac, 1991). The net CW charge is negative and results from weakly dissociating acidic groups having pKa values similar to those of poly-GalUA, the principal origin of the negative charges (Ritchie and Larkum, 1982; Saftner and Raschke, 1981; Richter and Dainty, 1989a; Buchanan et al., 2000). Some positive charges occur too, mainly associated with CW proteins (Cassab and Varner, 1988; Buchanan et al., 2000).

The CW determines cell dimensions (Taiz, 1984) and intracellular volume. The volume of the CW is a consequence of the dimensions of its internal spaces, i.e. the distances between the intra-CW units (Shomer et al., 1984; Shomer and Levy, 1988), which are determined by the repulsive strengths of diffuse double layers (Shomer et al., 1991). The swelling of parenchyma CW is restrained by the increase of valence and concentration of the exchangeable ions and with the decrease of the dielectric constant of the bulk solution (Shomer et al., 1991; Shomer, 1995). Although cell expansion and CW extension have been studied comprehensively (Cosgrove, 1997), the properties governing the volume of the CW, from the point of view of the dimensions of its internal spaces, deserve further elucidation. In any case, the volume of a CW matrix is affected by its electrical properties.

Several studies have demonstrated the importance of cell-surface electrical properties on plant-ion interactions. These include studies of ion uptake (Zhang et al., 2001; Kinraide, 2001, 2003), intoxication by ions such as Al3+, H+, and Na+ (Wagatsuma and Akiba, 1989; Suhayda et al., 1990; Nir et al., 1994; Yermiyahu et al., 1997; Kinraide, 1999), and alleviation of intoxication by Ca2+ and other ions (Kinraide, 1998). When whole cells or tissues, rather than plasma membrane (PM) vesicles, were used in the studies, the site of the electrostatic interactions was ambiguous and may have resided in the PM or CW or both.

The ζ-potentials (the near-surface potentials measured by electrophoresis) of protoplasts or PM vesicles have been measured from diverse sources and allow confirmation of a Gouy-Chapman-Stern model for the calculation of PM surface potentials (ψPM) in response to several monovalent, divalent, and trivalent ions (measurements compiled by Kinraide et al. [1998] and Kinraide [2001]). These studies agree remarkably well with studies of ion sorption by PM vesicles (Yermiyahu et al., 1997). ζ-Potentials of CWs have been measured (O'Shea et al., 1990), and CW potentials (ψWall) have been measured with microelectrodes pushed against the surfaces of cells (Nagai and Kishimoto, 1964; Spanswick et al., 1966; Saftner and Raschke, 1981). Nevertheless, studies of ψWall have been few and have included few ions (no highly intoxicating ions, other than H+, such as trivalent or heavy metal ions) and few combinations of ions. Indirect studies of CW electrical properties have been more common but have not led to estimations of ψWall. These studies included atomic adsorption analysis and potentiometric titration of exchangeable ions (Bush and McColl, 1987; Allan and Jarrell, 1989; Richter and Dainty, 1989b), charge density measurements (Richter and Dainty, 1990a), electron spin resonance (Irwin et al., 1985), and x-ray microanalysis (Campbell et al., 1981).

Consequently, we are not in a position to predict ψWall with the confidence with which we can predict ψPM. Preliminary to an attempted comprehensive treatment of electrostatic effects across the whole cell surface (wall and membrane), we have undertaken this study in which CW electrostatic behavior was monitored directly while changing the ionic conditions and pH of the bathing solution. The study included several novel or unusual features: The results were not influenced by the activity of viable PMs; ψWall was measured at the outer and inner surfaces of the CWs; ψWall was monitored continuously during transitions of ion type and concentration; responses to nearly 20 ions (including trivalent and heavy metal ions) were measured; interactive effects of two or more ions were measured; ψWall was considered in terms of electrostatic (Donnan) theory coupled to ion-binding models; and ψWall and ψPM were compared.

THEORY

Electrostatic and Ion-Binding Models

The electrical measurements were considered in terms of Donnan electrostatic theory coupled to ion-binding models. When the Donnan theory is combined with ion binding, we shall refer to it as the Donnan-plus-binding model. In an ideal system, the Donnan theory may be developed from the Nernst equation (Noble, 1991; and see below).

|

1 |

describes the partition of ion IZ according to its activity in the Donnan phase ({IZ}D), its activity in the bulk phase ({IZ}), its charge (Zi), and the electrical potential of the Donnan phase relative to the bulk phase (ψD). F/(RT) is the Faraday constant divided by the gas constant and the temperature. Equation 1 may be divided by Zi, and additional ions (e.g. JZ) may be added, yielding these equations.

|

2 |

|

3 |

The balance of charge within the Donnan phase may be written

|

4 |

In this equation, [R-]D is the concentration of confined or immobile charges, such as CW charges, and [IZ]D and [JZ]D are concentrations of ions IZ and JZ confined to the Donnan phase. The equation could be extended for any number of ions beyond IZ and JZ, but for simplicity, think of IZ and JZ being the cation and anion, respectively, in a single-salt solution. Furthermore, Equation 4 assumes no binding of ions to R-.

Equation 1 may be rewritten

|

5 |

The expression γi,D[R-]D/Zi - γi,DZj[JZ]D/Zi (= γi,D[IZ]D = {IZ}D) is derived from Equation 4. γi,D is the activity coefficient of ion IZ in the Donnan phase. Often, activity coefficients are omitted from considerations of Donnan equilibria, implicitly setting them all to 1. Equation 5 indicates that ψD is a linear function of ln{IZ} to the extent that ln{IZ}D is constant and that {IZ} dominates the solution. As {IZ} becomes very small, other ions such as H+, OH-, HCO3-, or contaminants will dominate the system, even in supposedly single-salt solutions, and ψD will come to a constant value, giving curvature to plots of ψD versus ln{IZ} or log10{IZ}.

Because [R-]D is the origin of the negative charges, a change in [R-]D will alter ψD, as indicated in Equation 5. [R-]D will change as cations bind to R- in the reaction R- + IZ → RIZi-1. In those cases, Equation 4 is incomplete because it should contain the species RIZi-1. The equations above can be expanded if the binding stoichiometry and an equilibrium constant (KR,I in units M-1) for the binding reaction, can be obtained. With that, the concentration of RIZi-1 can be computed from

|

6 |

where [IZ]D is the concentration of ion IZ in the Donnan phase. R- represents the negative binding sites in the Donnan phase. R- is a composite because a CW may have several classes of binding sites, and some may be much more accessible than others. Un-charged binding sites may be designated P0, and the concentration of PIZi can be computed from

|

7 |

In addition, binding stoichiometries may differ. For example, 1:1 charge-to-charge binding will produce only neutral R complexes (ZiR- + IZ → RZiI0).

In an ideal system, a Donnan phase is a homogeneous, macroscopic phase (such as the contents of a dialysis bag) in which all charges, including the confined charges R-, behave as freely mobile point sources of charge. In such a system, the location of a measuring electrode is not in doubt, and the precise computation of activity coefficients and Donnan-phase volumes is possible. Certainly the CW is not such a simple system. It is a meshwork of unevenly distributed, stationary charges. A microelectrode (large relative to the CW components) may have incomplete access the Donnan phase of the CW as we shall discuss later. Although the CW is not ideally suited to analysis by a simple Donnan-plus-binding model, we nevertheless applied the model to our data. Our approach was to optimize the parameters for the model so as to minimize the sum of squares of the difference between observed and computed ψWall. The parameters for the model included RTotal (the total concentration, in M units, of negative sites assuming no ion binding), a similar parameter for PTotal, KR,I (a binding constant for each ion IZ for the R- binding site), and KP,I (a binding constant for each ion IZ for the P0 binding site). The method of evaluating parameters is described in “Materials and Methods.”

RESULTS

Some Features of the Potentiometric Measurements

The electrical potentials for microelectrodes (actually glass micropipette salt bridges) in the tissue-bathing solution (the tip potentials) were less negative than -20 mV. Near the CW, the potentials became more negative, depending upon the bathing solution. Upon touching the CW, the ψWall acquired a constant value that did not change even as the electrodes were driven against the CW surfaces with greater force, thereby causing greater deformation. Eventually, the electrodes entered the cell interiors where the potentials jumped to about -120 mV in living cells.

In wheat (Triticum aestivum), values for ψWall were similar for living and heat-killed roots. Moreover, ongoing studies in Shomer's laboratory in Israel show that immunogold labeling of pectin in the CW itself is similar in both boiled potato (Solanum tuberosum) tubers and viable tubers, whereas the middle lamella is removed by boiling. Because ψWall was measured at the outer surface of whole roots (wheat) and at the inner and outer surface of potato cells (Fig. 1), the loss of pectin from the middle lamella would be expected to have little effect.

Figure 1.

Possible locations of the microelectrode tip in ghost cells of potato tuber.

The electrodes appeared to record ψWall very sensitively. Substitution of one bathing medium for another (NaCl for KCl or CaCl2 for MgCl2) caused changes in ψWall of a few millivolts, consistently in the same direction. The 2 or 3 m KCl electrode filling solution appeared not to affect the measurements. Addition of 0.1 mm KCl to a perfusion solution of 0.1 mm NaCl caused 20 mV depolarizations, indicating that the CW region under measurement was not swamped with concentrated KCl. Furthermore, micropipette filling solutions of 20 mm KCl produced the same values as 2 m KCl filling solutions.

Unbroken microelectrodes (tips generally taken to be <1 μm in diameter) and deliberately broken microelectrodes (tips >> 1 μm) yielded similar readings for ψWall. Furthermore, repeated measurements were similar. One may again and again withdraw the electrode from the cell surface, move the electrode to a new position, press the electrode onto the surface of the cell gently or firmly and observe similar readings each time.

Potato Cells

ψWall of ghost cells of potato tubers were measured as depicted in Figures 1 and 2 and as described in “Materials and Methods.” ψWall responded sensitively to changes in NaCl concentration in the bathing solution (Fig. 3A) and became less negative with increasing concentration. No hysteresis was apparent in ψWall with increasing or decreasing concentrations. KCl solutions affect ψWall nearly the same as NaCl (Figs. 4A). For both NaCl and KCl, ψWall increased by 30 to 35 mV from about -61 mV over the 100-fold concentration change from 0.1 to 10 mm.

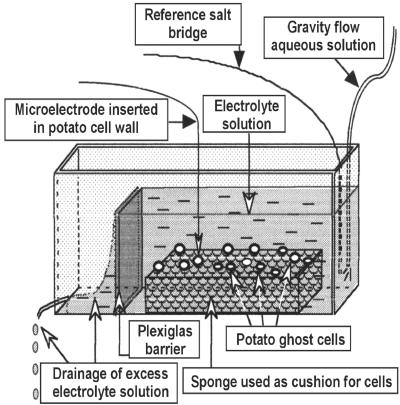

Figure 2.

A schematic representation of the experimental setup for measurement in ghost (heat killed) cells of potato tuber.

Figure 3.

CW potentials of potato tuber in changing concentrations of NaCl (A), CaCl2 (B), and AlCl3 (C). Arrows and values indicate times of solution changes and the concentrations in millimolar. For these, and for all potato measurements, single salts were used without adjustment of pH, unless stated otherwise.

Figure 4.

CW potentials of potato tuber in response to solute transitions among KCl, NaCl, Na2SO4, and K2SO4 (A) and in response to concentration changes in KCl (B). Arrows indicate the times of solution changes. Concentrations were 0.1 mm unless otherwise labeled.

The ψWall was more sensitive to low concentrations of multivalent cations such as Ca2+ and various Al species (Fig. 3, B and C) than to monovalent cations (Fig. 3A). ψWall increased by about 37 mV from about -59 mV over the 30-fold concentration change in CaCl2 from 0.1 to 3 mm. ψWall was sensitive to AlCl3 at much lower concentrations. It increased by about 30 mV from about -59 mV over the 5-fold concentration change in AlCl3 from 0.01 to 0.05 mm. However, [AlCl3] ≠ [Al3+] because of the formation of hydroxo-Al that was variable because the pH decreased as [AlCl3] increased (Kinraide and Parker, 1989).

Transitions from NaCl to KCl in the bathing solution induced less negative ψWall and vice versa (Fig. 4, A and B). These changes in ψWall were more pronounced with divalent anions, as when K2SO4 replaced Na2SO4 (Fig. 4A). A similar pattern was observed with divalent cations, as when CaCl2 replaced MgCl2 (Fig. 5B). Sulfate salts were more depolarizing than chloride salts (Fig. 5, A and B). The ψWall was also sensitive to pH changes (Fig. 5C). In the present study, each pH change was followed by CW equilibration with 0.1 mm NaCl solution. The potentials measured for pH 5.24 and 6.87 were -67.5 and -80.0 mV, respectively.

Figure 5.

CW potentials of potato tuber in response to solute transitions between CaSO4 and CaCl2 (A) and between Ca2+ and Mg2+ salts (B) and to changes in phosphate-buffered pH (C). Arrows indicate the times of solution changes. Concentrations were 0.1 mm unless otherwise labeled.

Figure 6 expresses ψWall for potato cells as a function of log10 of salt concentrations. Figures 4 through 6 demonstrate that the salts depolarize the CW with effectiveness in the order AlCl3 > CaCl2 ≥ MgCl2 > KCl ≥ NaCl. This is the expected trend—multi-charged ions were more effective at electrostatic screening, and binding strength probably declines in the same order, as it does in the case of PMs (Kinraide et al., 1998). Thus depolarization in the stated order is expected for two reasons: screening and charge elimination by binding.

Figure 6.

Measured and computed CW potentials of potato tuber in response to single-salt solutions. Because of hydrolysis, the pH of the AlCl3 solutions declined as the concentration increased.

Wheat Root Cells

Figures 7, 8, and 9 express ψWall for wheat cv Scout 66 root cells as a function of log10 concentration of salt solutions or log10{H+}. For each of the solutions, the response was linear or nearly linear, and the observed responses agree closely to a Donnan-plus-binding model to be described. Depolarizing effectiveness is in the order trivalent salts > H+ > divalent salts > monovalent salts. Our measurements indicate that positive potentials are rarely achieved in artificial solutions and would appear to be extremely rare in nature. For that to occur, pH would need to be less than 3 or other ions would need to exceed values commonly encountered. In a soil solution, where pH = 4.5, [Ca2+] = 1,000, and [Al3+] = 20 μm, ψPM = +4.3 mV (Kinraide et al., 1998), but ψWall would be strongly negative.

Figure 7.

CW potentials of wheat root in response to H+ and Na+. Parameters for the Donnan-plus-binding model were RTotal = 0.0211 m and KR,H = 9,450.

Figure 8.

CW potentials of wheat root in response to divalent cations. NaCl = 0.1 mm; pH = 5.6. Model parameters are as in Figure 7.

Figure 9.

CW potentials of wheat root in response to trivalent cations and H+. NaCl = 0.1 mm throughout. Model parameters are as in Figure 7. D, Chart record of LaCl3 added at time zero followed by transitions to AlCl3 to LaCl3 to AlCl3. For D, concentrations of LaCl3 and AlCl3 (the latter hydrolyzing slightly at pH 4.3) were selected to yield equal concentrations (108 μm) of Al3+ and La3+.

Using the method of solute substitutions, illustrated in Figures 4, 5B, and 9D, the following order of depolarizing effectiveness has been obtained for wheat CWs: Al3+ > La3+ > H+ > Cu2+ > Ni2+ > Ca2+ > Co2+ > Cd2+ > Mg2+ > Zn2+ > hexamethonium2+ > Rb+ > K+ > Cs+ >Na+. Compare this with the results from potato where Al3+ > Ca2+ > Mg2+ > K+ > Na+. This order indicates a possible role for ion size in depolarizing effectiveness: H+ was much more effective than other, larger, monovalent ions; Al3+ was more effective than the larger La3+; and each of the metallic divalent ions was more effective than the much larger hexamethonium2+. These examples refer to large size differences. Smaller size differences had no obvious effect.

The order of ions presented above resembles substantially the order of binding strength to CW pectinates (Franco et al., 2002). In addition, the following ions inhibit root elongation in wheat, in a basal medium of CaCl2, in this order: AlO4Al12(OH)24 (H2O)127+ > Sc3+ (may include some more highly charged polynuclear species) > Cu2+ > spermine4+ > Al3+ > La3+ > H+ > AlF2+ > Cs+ > Rb+ > tris(ethylenediamine)cobalt3+ > Zn2+ > AlF2+ > Li+ > Mg2+ > Ca2+ > K+ > Na+ (Kinraide, 1997, 1999; citations in the preceding and unreported results), indicating once again a role for charge and size.

Modeling and Comparisons among Studies

The present studies with potato tubers and wheat roots were performed independently (see “Materials and Methods”), so these and three published studies were compared. One of the studies employed electrophoresis, the others, microelectrodes. O'Shea et al. (1990) measured ζ-potentials in CW fragments of petiolar cells of Nymphoides peltata and Regnellidium diphyllum in a range of pH, [CaCl2], and [KCl]. Nagai and Kishimoto (1964) measured ψWall in Nitella flexilis in 0.01 to 100 mm KCl. Saftner and Raschke (1981) measured ψWall in guard cells of Commelina communis in 1 to 800 mm KCl at pH 7 and in 30 mm KCl at pH 2 to 7.

Preliminary inspection indicated that ψWall responses to solutes were similar among the studies, except that in the study of Saftner and Raschke (1981), values for ψWall were more negative. For example, in 1 mm KCl at pH 6 to 7, ψWall = -155 mV compared with ψWall ≈ -55 mV in the other studies. The principal difference among the other four studies is that plots of ψWall versus log10[NaCl] remained linear down to 0.1 mm in wheat (Fig. 7), whereas considerable curvature was seen in potato (Fig. 6) and in the study of Nagai and Kishimoto (1964).

We applied the Donnan-plus-binding model to 101 ψWall measurements from the five studies using a technique reported previously for the assessment of ψPM. In that study, ζ-potential measurements of PMs from eight studies were compiled (Kinraide et al., 1998; Kinraide, 2001), and parameter values for a Gouy-Chapman-Stern model were computed to minimize the sum of squared differences between calculated ψPM and measured ζ-potentials (see Fig. 10B). The parameters consisted of a universal set of optimized binding constants, but the intrinsic surface density of negative charge on the PM surface (σ0) was optimized separately for each of the eight studies. σ0 used in the Gouy-Chapman-Stern model is similar in function to RTotal in the Donnan-plus-binding model. The computed binding constants for the PM were these: KR,Na = KR,K = 0, KR,Mg = 23.8, KR,Ca = 29.1, KR,La = 2,030, KR,H = 20,200 m-1. These values, derived from electrophoretic studies of diverse species and tissues, agreed remarkable well with values determined by a sorption study of wheat root PMs (Yermiyahu et al., 1997).

Figure 10.

A comparison of studies in which CW and PM potentials were measured and computed. For A, parameters for the Donnan-plus-binding model were evaluated for five studies. Optimized values for RTotal were computed for each study, but binding constants (KR,H = 9,450; all others equal to zero) were evaluated for the pooled data. For B, parameters for the Gouy-Chapman-Stern model were evaluated similarly for eight studies. B is reproduced from Kinraide (2001) with permission.

Figure 10A presents measured versus computed ψWall for the five CW studies. The parameter values for RTotal are presented in the figure and confirm the preliminary observation that one of the studies differs from the others. The only other parameter to achieve a significant value was KR,H = 9,450 m-1, indicating an intrinsic pKa = 4.0 for the negative binding site. No significant value could be obtained for KP,H, indicating no binding of H+ to neutral sites. Weak or negligible binding of H+ to neutral sites may be concluded without computer modeling: Our studies indicated no reliable conversion of ψWall from negative to positive at pH 3 (Fig. 7A), and Saftner and Raschke (1981) obtained no charge conversion as pH was reduced to 2.

The failure of the model to detect binding of divalent and trivalent cations to the negative sites of the CWs was surprising given the readily modeled binding of these ions to the PMs, but Figures 7, 8, and 9 demonstrate that model-computed values for ψWall are in close agreement with observed values, usually. Exceptions are that in two studies, the measured values for ψWall were more positive than modeled for 0.1 mm NaCl at pH >5.5. These exceptions can be seen in Figure 10A as three outliers corresponding to y axis values between -60 to -80 mV. As mentioned above, these values give curvature to some plots that is not observed in others.

Figure 8 illustrates a generally close agreement between measured and computed values for ψWall in divalent cations. Nevertheless, the consistent tendency for the ions to depolarize ψWall in the order Cu2+ > Ca2+ > Zn2+ may be interpreted to mean some, perhaps small, binding in the same order. In addition, consistent differences between the depolarizing effectiveness of Na+ and K+ and between Al3+ and La3+ were observed too.

A Comparison of ψWall and ψPM

Of interest to those who seek to understand electrostatic effects across the whole cell surface (wall and membrane) is the similarity of response of ψWall and ψPM to solutes. Table I presents measured and computed ψWall and computed ψPM. A detailed look at the values is instructive. The third row from bottom presents the most negative values in what may be considered to be the “basal” medium. Additions of LaCl3 to this medium, or reductions of pH, reduce the negativity of ψPM much more than ψWall, as would be expected from the PM-binding constants KR,La = 2,200 and KR,H = 215,000. Additions of CaCl2 have very similar effects on both ψWall and ψPM, but additions of NaCl reduce the negativity of ψWall more than ψPM. These latter effects are somewhat coincidental. If the parameters σ0 and KR,H for the Gouy-Chapman-Stern model were reduced, then ψWall and ψPM responded similarly to changes in NaCl. In any case, measured ψWall and computed ψPM are correlated (R = 0.771), and the deviations can be interpreted readily.

Table I.

Measured and computed electrical potentials in some solutions

Values for ψWall, measured were taken from the fitted curves in Figures 7 and 9 and from a curve fitted to the pooled data from Figure 8, A through C. Concentrations are in millimolar and potentials in millivolts.

| LaCl3 | pH | CaCl2 | NaCl | ψWall, measured | ψWall, computeda | ψPM, computedb |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.001 | 5.6 | 0 | 0.1 | −78.9 | −72.0 | −44.6 |

| 0.01 | 5.6 | 0 | 0.1 | −55.7 | −54.2 | −25.4 |

| 0.1 | 5.6 | 0 | 0.1 | −32.5 | −35.5 | −6.0 |

| 1 | 5.6 | 0 | 0.1 | −9.3 | −16.9 | 12.7 |

| 0 | 5.00 | 0 | 0.1 | −87.4 | −94.7 | −71.0 |

| 0 | 4.00 | 0 | 0.1 | −54.0 | −59.1 | −16.5 |

| 0 | 3.00 | 0 | 0.1 | −9.4 | −13.1 | 34.6 |

| 0 | 5.6 | 0.01 | 0.1 | −88.6 | −81.2 | −85.1 |

| 0 | 5.6 | 0.1 | 0.1 | −60.1 | −56.6 | −62.8 |

| 0 | 5.6 | 1 | 0.1 | −31.6 | −29.5 | −36.1 |

| 0 | 5.6 | 0 | 0.1 | −98.6 | −110.6 | −101.3 |

| 0 | 5.6 | 0 | 1 | −57.5 | −70.2 | −85.5 |

| 0 | 5.6 | 0 | 10 | −16.4 | −22.5 | −59.0 |

a Parameter values for the Donnan-plus-binding model: RTotal = 0.0211 m and KR,H = 9450.

b ψPM, computed was computed by a Gouy-Chapman-Stern model (Kinraide et al., 1998) in which negative-site binding constants are KR,Na = I, KR,Ca = 30, KR,La = 2,200, KR,H = 21,500 m−1.

DISCUSSION

The values for ψWall measured independently in four laboratories were similar whether measured by electrophoresis of CW fragments (O'Shea et al., 1990) or by microelectrode placement against the CWs of whole cells that were living or heat killed (Nagai and Kishimoto, 1964; present study). ψWall responses to H+ and to monovalent, divalent, and trivalent cations were described successfully by Donnan theory combined with H+ binding to a negative CW site.

Measured values for ψWall were often similar to computed values for ψPM, and differences can be interpreted mainly on the basis of differences in the strength of ion binding to CWs and PMs. We conclude that ion binding, at least to readily accessible sites, is stronger at PM surfaces than to CW components. This follows from the evaluation of parameters for the electrostatic models and from the fact that ψWall was more resistant than ψPM to conversion to positive values.

An advantage of continuous potentiometric measurements with microelectrodes is that small differences in the depolarizing effectiveness of the ions can be determined. That effectiveness follows the order Al3+ > La3+ > H+ > Cu2+ > Ni2+ > Ca2+ > Co2+ > Cd2+ > Mg2+ > Zn2+ > hexamethonium2+ > Rb+ > K+ > Cs+ > Na+. We did not attempt to model all ion effects such as the differences between SO42- and Cl- as counter ions or differences among some ions within a charge class (e.g. Na+ versus K+ or Ca2+ versus Mg2+). These differences may reflect different binding strengths at similar binding sites or access to a greater number of binding sites by some ions. In any case, the sequence of depolarizing effectiveness was readily determined by monitoring ψWall as one salt solution was substituted for another. Furthermore, this sequence resembles, but is not identical to, binding to CW pectinates and to the intoxication of roots.

An item of concern is the low value for estimated charge concentration (RTotal) for four of the studies. Estimates by other methods yielded values ranging from 0.1 to 1.5 m, as reviewed by Grignon and Sentenac (1991). We offer three hypotheses for low values for RTotal. The first is a dilution effect. A microelectrode may accesses simultaneously the Donnan phase and the bulk phase of the medium. Problematical to the hypothesis of a dilution effect is that unbroken and deliberately broken microelectrodes yielded similar readings as do readings taken from different positions (see “Some Features of the Potentiometric Measurements” under “Results”).

Perhaps even the sharpest electrodes fail to embed entirely within the CW as illustrated in the second from left diagram in Figure 1. Perhaps all electrodes merely touch the surface of the CW. The important factor may be the contact between the rim of the electrode orifice and the CW, and a large-circumference electrode may work just as well as a small one, provided the entire rim makes contact with the CW surface. This thinking leads to the second hypothesis: The measured potential is a CW surface potential, not an interior potential. This concept could explain the fact that the ζ-potentials measured by O'Shea et al. (1990) also appear to be insufficiently negative for RTotal > 0.1 m.

The third hypothesis for low computed values for RTotal may be that some of the negative sites were not in equilibrium with the bathing medium. Perhaps some carboxyl groups were bridged by Ca2+ within a lattice so that the Ca2+ and the negative charges were inaccessible to exchange with other ions or were unable to dissociate freely. This is in accordance with the calcium-pectate egg-box model (Grant et al., 1973) and the localization of various pectin fractions including high or low methoxyl pectin and calcium-pectate (Bush and McCann, 1999). In that case, RAccessible < RTotal. Consistent with this view is that additions or withdrawals of solutes caused decreases or increases in ψWall negativity that were complete within 1 or 2 min. After that, ψWall remained constant. Additions of 0.1 or 1 mm EDTA adjusted to pH 5.6 with NaOH did not alter ψWall beyond the effects attributable to Na+. This almost certainly indicates that some of the CW-bound Ca2+ was not readily accessible.

We cannot explain the more highly negative values presented by Saftner and Raschke (1981). Perhaps the leaf cells really did have a more negative RTotal. In a side study in Kinraide's laboratory, ψWall was measured in roots of monocots and dicots. It is well documented that the latter have a higher cation exchange capacity than the former (Marschner, 1995). In each of the concentrations 0.1, 1, and 10 mm KCl, ψWall was unvaryingly negative in the order radish (Raphanus sativus) > turnip > maize (Zea mays) > wheat. The greater negativity of dicot CWs was statistically significant according to measurements obtained and compiled by a naïve observer. Thus the electrodes accessed potentials related to the expected Donnan potentials.

Despite the concerns just mentioned (inability to model the binding of ions other than H+ and a low value for computed RTotal), a simple model with only one universal adjustable parameter (KR,H) and one adjustable parameter for each of the five studies (RTotal) generated values for ψWall that correlate highly with measured values (R = 0.964; Fig. 10A). We consider it likely that both measured or computed values for ψWall are at least proportional to, if not equal to, actual ψWall. Consequently, computed ion activities in the Donnan phase are likely to be proportional to, if not equal to, actual Donnan-phase activities. Proportional, of course, means that actual ψWall = 0 when measured ψWall = 0. This is almost certainly correct because reduced access to the Donnan phase will reduce the magnitude of but will not change the sign of ψWall.

Cell-surface electrostatic effects influence ion uptake, ion-induced intoxication, and ion alleviation of intoxication, but less-studied physiological effects are under electrostatic control as well. Changes in the valence and concentration of the exchangeable ions, as well as the dielectric constant of the aqueous medium, play a role in the CW swelling pressure (Shomer et al., 1991). Reductions in the negativity of ψWall and the thickness of the electric double layer decrease the electrostatic repulsion between CW units. This decreases the swelling pressure and retards the CW swelling, thus resulting in smaller cells and organs as a whole. These morphological changes, as well as the changes in ion activity, may play a role in CW-specific plant responses to salinity and a variety of other environmental challenges. Some practical consequences of changes in ψWall may include food tissue responses important to nutrient status, ripening, storage, pathogen resistance, and texture.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The ψWall responses were measured in two different tissues (potato [Solanum tuberosum] tuber and wheat [Triticum aestivum L. cv Scout 66] root) of either viable or heat-killed (ghost) cells. The measurements of ψWall in potato were performed at the University of Missouri. Later, measurements of ψWall in wheat began at the Appalachian Farming Systems Research Center. After the Missouri work had been completed, and while the Appalachian work was in progress, the investigators became aware of each other's studies and decided to conflate their reports.

The ψWall was measured by adapting methods used for measuring transmembrane electrical potentials (Lüttge and Higinbotham, 1979). Potato tuber cells were especially suitable for this purpose because heating (at 100°C) inactivates the protoplast, whereas the gelatinized starch inflates the cell lumen, cushions the CW, and stabilizes the inserted microelectrode tip in the CW for the duration of the measurement. Ghost cells were prepared by boiling peeled tuber dices (approximately 3 cm3 including cortex and parenchyma tissues) for 20 min, mashing, and rinsing several times with distilled water. The macerate was strained through a 0.1-mm mesh under a stream of distilled water. The sieved macerate was rinsed and suspended in a column of distilled water. Large, quick-settling and small, slow-settling cells and aggregates were discarded, leaving a suspension of medium-sized cells (4-5 × 10-3 mm3 [Shomer, 1995]) for ψWall measurements.

The microelectrodes were prepared from microcapillaries with glass microfibers (WP Instruments, Sarasota, FL) that were drawn into micropipettes with a vertical pipette puller (D. Kopf Company, Tujunga, CA). Tip diameter was <0.5 μm, tip potential was -5 to -15 mV, and resistance was 5 to 15 mΩ. The micropipette was filled with 3 m KCl representing one salt bridge, and a 3 m KCl/3% (w/v) agar salt bridge was used as reference. Both bridges were connected via Ag/AgCl electrodes to an electrometer (WPI Intra 767) and strip chart recorder.

The electrical measurements were conducted in a 35-× 5-× 16-mm Plexiglas chamber containing electrolytic solution with a fine sponge attached to the bottom (Fig. 2). One drop of cells suspended in water (1:10, v/v; Shomer et al., 1995) was added to the bath. The cells settled in the Plexiglas chamber, and each cell was held stationary in a separate sponge cavity. The micropipette was inserted into the CW of a visible single ghost cell (biologically inactive) using a micromanipulator under a horizontal microscope. The microelectrode tip was stabilized in the CW as shown in Figure 1, State 2, where the gelatinized starch cushioned the CW against collapse under the pressure exerted by the microelectrode.

The chamber was perfused with various test solutions at a constant flow rate of 1 mL s-1, thereby accelerating the response when the electrolyte was changed and minimizing interfacial concentration gradients and possible interference from the 3 m KCl of the microelectrode. Each ψWall measurement in each solution was held, if possible, until the reading stabilized. The microelectrode tip was very sensitive to ψWall; no matter where the tip contacted the CW (Fig. 1, States 1, 2, and 4), there was no difference in ψWall. Therefore, the penetration of the microelectrode tip into the CW did not cause aberrations in the electrical measurements. Nevertheless, the ψWall differed somewhat from cell to cell (in the range of -65 to -75 mV without added salts). Unless stated otherwise, the pH of the solutions was about 5.6.

The method of ψWall measurement in wheat roots was similar in most respects to the method used in potato. Whole seedling were mounted in a clear plastic chamber and perfused with test solutions. Electrodes, filled with 2 m KCl, were pushed against the surfaces of root-surface cells. Some seedlings were dipped into boiling water for a few seconds, but a large number of measurements were made on living roots too. The reason for using boiled tissue (a technique adopted independently in Missouri and West Virginia) was that an electrode at the CW surface often penetrated the PM, thereby measuring a transmembrane potential difference. Furthermore, the continuing elongation of live roots caused instabilities in the measurements. Aluminum solutions for the wheat work were adjusted so that the ion activity ratio {Al3+}/{H+}3 # 108.8 (activities in m), thereby ensuring the absence of solid-phase or polynuclear Al (Kinraide and Parker, 1989).

We evaluated the parameters for the model (see “Theory”) so as to minimize the sum of squares of the differences between observed and computed ψWall. The method consisted of an automated assessment of trial values for one parameter while holding all others constant. That parameter was then held constant at its temporary optimum, and trial values for another parameter were assessed. The process was iterated with increasing precision until the sum of squares was minimized. False terminations of the program sometimes occurred, but these could be detected by using different starting values for the parameters.

Distribution of Materials

Upon request, all novel materials described in this publication will be made available in a timely manner for noncommercial research, subject to the requisite permission, obtained by the requestor, from any third-party owners of the materials.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dean Ann Farris for her assistance in measuring wheat root ψWall.

This work was supported by the Agricultural Research Organization, The Volcani Center, Israel, by the University of Missouri, Columbia and by the United States-Israel Binational Agricultural Research and Development Fund (grant nos. IS-3120-99R and IS-1425-88R).

References

- Allan DL, Jarrell WM (1989) Proton and copper adsorption to maize soybean root cell walls. Plant Physiol 89: 823-832 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Briggs GE, Robertson RN (1957) Apparent free space. Annu Rev Plant Physiol 8: 11-30 [Google Scholar]

- Buchanan BB, Gruissem W, Jones RL (2000) Biochemistry and Molecular Biology of Plants. American Society of Plant Physiologists, Rockville, MD

- Bush MS, McCann MC (1999) Pectic epitopes are differentially distributed in the cell walls of potato (Solanum tuberosum) tubers. Physiol Plant 107: 201-213 [Google Scholar]

- Bush DS, McColl JG (1987) Mass-action expression of ion exchange applied to Ca2+, H+, K+, and Mg2+ sorption on isolated cell walls of leaves from Brassica oleracea. Plant Physiol 85: 247-260 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell NA, Satter RL, Garber RC (1981) Apoplastic transport of ions in the motor organ of Samanea. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 78: 2981-2984 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cassab GI, Varner JE (1988) Cell wall proteins. Annu Rev Plant Physiol Plant Mol Biol 39: 321-353 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cosgrove DJ (1997) Assembly and enlargement of the primary cell wall in plants. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol 13: 171-201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franco CR, Chagas AP, Jorge RA (2002) Ion-exchange equilibria with aluminum pectinates. Colloids Surf 204: 183-192 [Google Scholar]

- Gillet C, Lefèbvre J (1981) Estimation of the anion-exchange capacity of the cell wall of Nitella flexilis. J Appl Polym Sci 25: 2829-2843 [Google Scholar]

- Grant GT, Morris ER, Rees DA, Smith PJS, Thom D (1973) Biological interactions between polysaccharides and divalent cations: egg-box model. FEBS Lett 32: 195-198 [Google Scholar]

- Grignon C, Sentenac H (1991) pH and ionic conditions in the apoplast. Annu Rev Plant Physiol Plant Mol Biol 42: 103-128 [Google Scholar]

- Irwin PL, Sevilla MDS, Stoudt CL (1985) ESR spectroscopic evidence for hydration- and temperature-dependent spatial perturbation of a higher plant cell wall paramagnetic ion lattice. Biochim Biophys Acta 842: 76-83 [Google Scholar]

- Kinraide TB (1997) Reconsidering the rhizotoxicity of hydroxyl, sulphate, and fluoride complexes of aluminium. J Exp Bot 48: 1115-1124 [Google Scholar]

- Kinraide TB (1998) Three mechanisms for the calcium alleviation of mineral toxicities. Plant Physiol 118: 513-520 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinraide TB (1999) Interactions among Ca2+, Na+ and K+ in salinity toxicity: quantitative resolution of multiple toxic and ameliorative effects. J Exp Bot 50: 1495-1505 [Google Scholar]

- Kinraide TB (2001) Ion fluxes considered in terms of membrane-surface electrical potentials. Aust J Plant Physiol 28: 607-618 [Google Scholar]

- Kinraide TB (2003) The controlling influence of cell-surface electrical potential on the uptake and toxicity of selenate (SeO42-). Physiol Plant 117: 64-71 [Google Scholar]

- Kinraide TB, Parker DR (1989) Assessing the phytotoxicity of mononuclear hydroxy-aluminum. Plant Cell Environ 12: 479-487 [Google Scholar]

- Kinraide TB, Yermiyahu U, Rytwo G (1998) Computation of surface electrical potentials of plant cell membranes: correspondence to published zeta potentials from diverse plant sources. Plant Physiol 118: 505-512 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lüttge U, Higinbotham N (1979) Transport in Plants. Springer-Verlag, New York

- Marschner H (1995) Mineral Nutrition of Higher Plants, Ed 2. Academic Press, London

- Nagai R, Kishimoto U (1964) Cell wall potential in Nitella. Plant Cell Physiol 5: 21-31 [Google Scholar]

- Nir S, Rytwo G, Yermiyahu U, Margulies L (1994) A model for cation adsorption to clays and membranes. Colloid Polym Sci 272: 619-632 [Google Scholar]

- Noble PS (1991) Physicochemical and Environmental Plant Physiology. Academic Press, London

- O'Shea P, Walters J, Ridge I, Wainright M, Trinci APJ (1990) Zeta potential measurements of cell wall preparations from Regnellidium diphyllum and Nymphoides peltata. Plant Cell Environ 13: 447-454 [Google Scholar]

- Richter C, Dainty J (1989a) Ion behavior in plant cell wall: I. Characterization of the Sphagnum russowii cell wall ion exchanger. Can J Bot 67: 451-459 [Google Scholar]

- Richter C, Dainty JH (1989b) Ion behavior in plant cell wall: II. Measurement of the free space, anion-exclusion space, anion-exchange capacity, and cation-exchange capacity in delignified Sphagnum russowii cell wall. Can J Bot 67: 460-465 [Google Scholar]

- Richter C, Dainty J (1990a) Ion behavior in plant cell wall: III. Measurement of the mean charge density parameter in delignified Sphagnum russowii cell walls. Can J Bot 68: 768-772 [Google Scholar]

- Richter C, Dainty J (1990b) Ion behavior in plant cell wall: IV. Selective cation binding by Sphagnum russowii cell walls. Can J Bot 68: 773-781 [Google Scholar]

- Ritchie RJ, Larkum AWD (1982) Cation exchange properties of the cell walls of Enteromorpha intestinalis (L.) link. (Ulvales Chlorophyta). J Exp Bot 132: 125-139 [Google Scholar]

- Saftner RA, Raschke K (1981) Electrical potentials in stomatal complexes. Plant Physiol 67: 1124-1132 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sentenac H, Grignon C (1981) A model for predicting ionic equilibrium concentrations in cell walls. Plant Physiol 68: 415-419 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shomer I (1995) Swelling behaviour of cell wall and starch in potato (Solanum tuberosum L.) tuber cells: I. Starch leakage and structure of single cells. Carbohydr Polym 26: 47-54 [Google Scholar]

- Shomer I, Frenkel H, Polinger C (1991) The existence of a diffuse electric layer at cellulose fibril surfaces and its role in the swelling mechanism of parenchyma plant cell walls. Carbohydr Polym 16: 199-210 [Google Scholar]

- Shomer I, Levy D (1988) Cell wall mediated bulkiness as related to the texture of potato (Solanum tuberosum L.) tuber tissue. Potato Res 31: 321-334 [Google Scholar]

- Shomer I, Lindner P, Vasiliver R (1984) Mechanism which enables the cell wall to retain homogeneous appearance of tomato juice. J Food Sci 49: 628-633 [Google Scholar]

- Shomer I, Vasiliver R, Lindner P (1995) Swelling behaviour of cell wall and starch in potato (Solanum tuberosum L.) tuber cells: II. Permeability and swelling in macerates. Carbohydr Polym 26: 55-59 [Google Scholar]

- Spanswick RM, Stolarek J, Williams EJ (1966) The membrane potential of Nitella translucens. J Exp Bot 18: 1-16 [Google Scholar]

- Suhayda CG, Giannini JL, Briskin DP, Shannon MC (1990) Electrostatic changes in Lycopersicon esculentum root plasma membrane resulting from salt stress. Plant Physiol 93: 471-478 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taiz L (1984) Plant cell expansion: regulation of cell wall mechanical properties. Annu Rev Plant Physiol 35: 585-657 [Google Scholar]

- Wagatsuma T, Akiba R (1989) Low surface negativity of root protoplasts from aluminum-tolerant plant species. Soil Sci Plant Nutr 35: 443-452 [Google Scholar]

- Yermiyahu U, Rytwo G, Brauer DK, Kinraide TB (1997) Binding and electrostatic attraction of lanthanum (La3+) and aluminum (Al3+) to wheat root plasma membranes. J Membr Biol 159: 239-252 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Q, Smith FA, Sekimoto H, Reid RJ (2001) Effect of membrane surface charge on nickel uptake by purified mung bean root protoplasts. Planta 213: 788-793 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]