There are estimated to be >42 million people worldwide who live with HIV-1 infection. Any novel means of treating infection therefore will be greeted with great interest. The current generation of antiretroviral drugs inhibits the viral enzymes, reverse transcriptase and protease (1), and where available has resulted in a 65% reduction of AIDS mortality. Nevertheless, new drugs will be needed as drug resistance emerges, and all steps in the replication of HIV-1 are fair game as potential drug targets (Fig. 1).

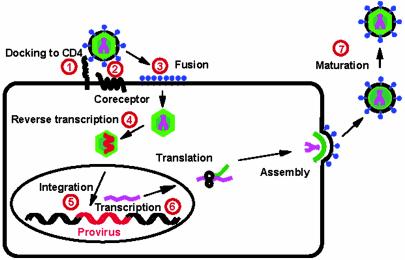

Fig. 1.

Simplified replication cycle of HIV-1. Several of the steps that can be blocked by actual or potential drugs are numbered: 1, docking to CD4, the topic of this commentary; 2, interaction with the chemokine coreceptor; 3, inhibiting fusion of the viral envelope with the cell membrane; 4, reverse transcriptase inhibitors; 5, integrase inhibitors; 6, prevention of viral transcription such as Tat antagonists; and 7, protease inhibitors. Attacking the virus with several drugs in combination has been the key to successful clinical therapy thus far.

In this issue of PNAS, Pin-Fang Lin and colleagues at Bristol-Myers Squibb (2) describe a small molecular weight inhibitor of HIV-1 infection that acts by blocking the very first step in the infection process, namely, the binding of the viral envelope glycoprotein (gp120) to its cell surface receptor, CD4. BMS-378806 is a newly synthesized molecule that competes for the niche that serves as the binding pocket for CD4 on gp120. BMS-378806 could be a potent antiretroviral drug for those strains of HIV-1 that are sensitive to its blocking effect, because pre-clinical tests indicate that it exhibits pharmacological activity at nanomolar concentrations, is minimally toxic, and can be administered orally. As with other antiretroviral drugs, however, Lin et al. (2) show that drug resistance evolves rapidly under selection.

The early discovery that CD4 is involved in HIV infection (3, 4) explained why CD4-expressing T helper lymphocytes are selectively depleted in AIDS. All strains of HIV-1, HIV-2, and simian immunodeficiency virus bind to CD4 (5). Accessory cell surface molecules called coreceptors, shown to be chemokine receptors (either CCR5 or CXCR4), are required for fusion with the cell membrane (6). Anti-HIV compounds that block coreceptors† and membrane fusion (7) are in preliminary clinical trials, but BMS-378806 is the first small molecule to block the gp120-CD4 binding event.

It is curious that a small molecule inhibitor of the gp120–CD4 interaction has not been reported previously, because there has been much interest in interfering with this first step in infection. In the late 1980s, various recombinant, soluble proteins derived from the N-terminal domains of CD4 were shown to be potent inhibitors of laboratory strains of HIV-1, but they were found to be ineffective for primary strains of HIV-1 (8). More recently, a fusion protein of CD4 with Ig (PRO542) has shown promise as an efficient drug blocking the gp120 binding site (9). PRO542 and a CD4-based peptide tested in vitro (10) have the disadvantage of requiring injection and possibly being antigenic, but may have the advantage of inhibiting all strains of HIV and thus may not lead to HIV resistance so readily. However, certain mutants of HIV-1 have been selected in vitro to infect cells independently of CD4 by interacting directly with CCR5 or CXCR4 (11–13). It will be interesting to see whether inhibitors of CD4 binding select for this type of virus, although there is no evidence to date that CD4-independent strains of HIV-1 emerge in vivo.

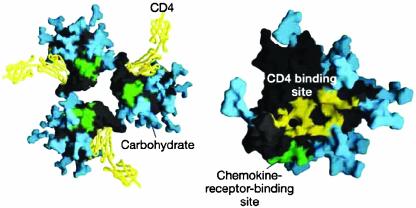

The gp120 trimer on the virus surface undergoes conformational changes on interacting first with CD4 and then with CCR5 or CXCR4. Binding to multiple receptors can be efficient while access by antibodies may be masked (14). The structure of gp120 complexed to CD4 has been solved (15), and its functional surface is depicted in Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

Surface structure of HIV-1 gp120 complexed to CD4. (Left) The trimeric form of gp120 as assembled on the virus particle is shown, with soluble CD4 domains 1 and 2 (yellow) locked into the receptor binding pocket. Green shows the putative chemokine receptor binding site, and blue shows the carbohydrate moieties on this heavily glycosylated protein. (Right) A rotated and magnified view of a single gp120 surface is shown with the CD4-binding site colored yellow. [Reproduced with permission from ref. 14 (Copyright 2002, Nature Publishing Group, www.nature.com).]

gp120–CD4 interaction is a target not only for drugs but also for candidate vaccines mediated through humoral immunity. The CD4 binding site on gp120 is one of the better conserved antigenic epitopes in an otherwise highly variable envelope. A human mAb, b12, recognizes the CD4 binding site on gp120, and it is able to neutralize many virus isolates derived from different subtypes of HIV-1 (16). There is an urgent need for vaccine candidates that elicit b12-like antibodies (17).

BMS-378806 was selected to inhibit a subtype B strain of HIV-1. Lin et al. (2) report that it is weaker at blocking infection of more distantly related HIV-1 strains, such as some of those prevalent in Africa and Asia, although efficacious levels of drug may still be achievable in many cases. The drug does not inhibit HIV-2 or simian immunodeficiency virus at all, even though these viruses also bind to CD4 (5). These observations indicate that BMS-378806 should be regarded as a first-generation molecule. Improved inhibitors may be derived from a structural elucidation to ascertain whether BMS378806 really fits into the CD4 binding pocket on gp120, and from analyses of the amino acid changes in the resistant mutants described in the report by Lin et al. (2). Some of the mutations lie outside the CD4 binding pocket of gp120; some are even in gp41, the transmembrane protein that tethers gp120 to the virus envelope and mediates membrane fusion. Thus the topology of the pocket appears to be influenced by the overall structure of the gp120/gp41 complex. New compounds that fit into the CD4-binding pocket more snugly might exhibit greater potency for diverse HIV strains, a lower rate of evolution of HIV resistance, and possibly a lower fitness of resistant mutants when they emerge. All in all, BMS-378806 is a most promising start.

See companion article on page 11013.

Footnotes

Dorr, P., Macartney, M., Rickett, G., Smith-Burchnell, C., Dobbs, S., Mori, J., Griffin, P., Lok, J., Irvine, R., Westby, M., et al., 10th Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections, Feb. 10–14, 2003, Boston, www.retroconference.org/2003/Abstract/search.aspx (abstr.).

References

- 1.Pomerantz, R. J. & Horn, D. L. (2003) Nat. Med. 9, 867–873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lin, P.-F., Blair, W., Wang, T., Spicer, T., Guo, Q., Zhou, N., Gong, Y.-F., Wang, H.-G. H., Rose, R., Yamanaka, G., et al. (2003) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 100, 11013–11018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dalgleish, A. G., Beverley, P. C., Clapham, P. R., Crawford, D. H., Greaves, M. F. & Weiss, R. A. (1984) Nature 312, 763–767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Klatzmann, D., Champagne, E., Chamaret, S., Gruest, J., Guetard, D., Hercend, T., Gluckman, J. C. & Montagnier, L. (1984) Nature 312, 767–768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sattentau, Q. J., Clapham, P. R., Weiss, R. A., Beverley, P. C., Montagnier, L., Alhalabi, M. F., Gluckmann, J. C. & Klatzmann, D. (1988) AIDS 2, 101–105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Berger, E. A., Murphy, P. M. & Farber, J. M. (1999) Annu. Rev. Immunol. 17, 657–700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lalezari, J. P., Henry, K., O'Hearn, M., Montaner, J. S., Piliero, P. J., Trottier, B., Walmsley, S., Cohen, C., Kuritzkes, D. R., Eron, J. J., Jr., et al. (2003) N. Engl. J. Med. 348, 2175–2185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Daar, E. S., Li, X. L., Moudgil, T. & Ho, D. D. (1990) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 87, 6574–6578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jacobson, J. M., Lowy, I., Fletcher, C. V., O'Neill, T. J., Tran, D. N., Ketas, T. J., Trkola, A., Klotman, M. E., Maddon, P. J., Olson, W. C. & Israel, R. J. (2000) J. Infect. Dis. 182, 326–329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Martin, L., Stricher, F., Misse, D., Sironi, F., Pugniere, M., Barthe, P., Prado-Gotor, R., Freulon, I., Magne, X., Roumestand, C., et al. (2003) Nat. Biotechnol. 21, 71–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dumonceaux, J., Nisole, S., Chanel, C., Quivet, L., Amara, A., Baleux, F., Briand, P. & Hazan, U. (1998) J. Virol. 72, 512–519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hoffman, T. L., LaBranche, C. C., Zhang, W., Canziani, G., Robinson, J., Chaiken, I., Hoxie, J. A. & Doms, R. W. (1999) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96, 6359–6364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kolchinsky, P., Mirzabekov, T., Farzan, M., Kiprilov, E., Cayabyab, M., Mooney, L. J., Choe, H. & Sodroski, J. (1999) J. Virol. 73, 8120–8126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kwong, P. D., Doyle, M. L., Casper, D. J., Cicala, C., Leavitt, S. A., Majeed, S., Steenbeke, T. D., Venturi, M., Chaiken, I., Fung, M., et al. (2002) Nature 420, 678–682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kwong, P. D., Wyatt, R., Robinson, J., Sweet, R. W., Sodroski, J. & Hendrickson, W. A. (1998) Nature 393, 648–659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Burton, D. R., Pyati, J., Koduri, R., Sharp, S. J., Thornton, G. B., Parren, P. W., Sawyer, L. S., Hendry, R. M., Dunlop, N., Nara, P. L., et al. (1994) Science 266, 1024–1027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McMichael, A. J. & Hanke, T. (2003) Nat. Med. 9, 874–880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]