Abstract

Core antigen (cAg), the viral capsid, is one of the three major clinical antigens of hepatitis B virus. cAg has been described as presenting either one or two conformational epitopes involving the “immunodominant loop.” We have investigated cAg antigenicity by cryo-electron microscopy at ≈11-Å resolution of capsids labeled with monoclonal Fabs, combined with molecular modeling, and describe here two conformational epitopes. Both Fabs bind to the dimeric external spikes, and each epitope has contributions from the loops on both subunits, explaining their discontinuous nature: however, their binding aspects and epitopes differ markedly. To date, four cAg epitopes have been characterized: all are distinct. Although only two regions of the capsid surface are accessible to antibodies, local clustering of the limited number of exposed peptide loops generates a potentially extensive set of discontinuous epitopes. This diversity has not been evident from competition experiments because of steric interference effects. These observations suggest an explanation for the distinction between cAg and e-antigen (an unassembled form of capsid protein) and an approach to immunodiagnosis, exploiting the diversity of cAg epitopes.

Keywords: steric blocking, cryo-electron microscopy, macromolecular docking, discontinuous epitope

Despite success with vaccines and antiviral drugs, hepatitis B virus (HBV) remains a major public health problem (1), motivating efforts to further elucidate its antigenic makeup and replication cycle. The virus has a relatively simple structure, consisting of a nucleocapsid contained within a lipoprotein envelope. Clinically, three major antigens have been distinguished: surface antigen (sAg), the envelope glycoprotein that is also present in large membranous aggregates in the sera of infected individuals; and core antigen (cAg) and e-antigen (eAg), which represent assembled and unassembled variants of the capsid protein (Fig. 1a). sAg has been used as a protective antigen in vaccines, whereas cAg and eAg have served primarily for diagnostic purposes to assess the course of infections (2).

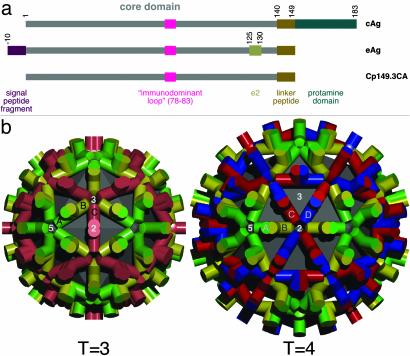

Fig. 1.

(a) Diagram comparing the cAg and eAg variants of the HBV capsid protein and the construct used in these studies. The terminal peptides and immunologically relevant sites are marked. (b) Schematic models of the packing of dimeric building blocks in the two icosahedral capsids, T = 3 and T = 4, viewed along axes of 2-fold symmetry. The quasi-equivalent subunits are coded in different colors. The T = 3 capsid is composed of A–B and C–C dimers: A subunit, green; B subunit, yellow; C subunit, red. The T = 4 capsid is composed of A–B and C–D dimers: A subunit, green; B subunit, yellow; C subunit, red; D subunit, blue.

The cAg polypeptide consists of a core domain (residues 1–140) and an Arg-rich “protamine” domain (residues 150–183), connected by a linker peptide. eAg lacks the protamine domain but retains a fragment of signal sequence (Fig. 1a). Core domains dimerize to form building blocks capable of self-assembly into capsids (3, 4), whereas the protamine domains bind nucleic acids and are tethered to the capsid inner surface by the linker peptide (5). The primarily α-helical fold of the core domain has been determined (6–8), and a conformation has been proposed for the linker peptide (5), but the structure of the protamine domain (if it has a specific fold) is unknown. With full-length linker, most capsids consist of 120 icosahedrally coordinated dimers, i.e., they have a triangulation number T = 4, with four quasi-equivalent subunits (A–D, see Fig. 1b). The remainder are slightly smaller, T = 3 (90 dimers, and three quasi-equivalent subunits, A–C). In principle, the T = 4 capsid presents 240 copies of each epitope in four quasi-equivalent variants, and the T = 3 capsid, 180 copies in three quasi-equivalent variants.

Upon the advent of mAb technology, much effort was invested in raising and characterizing mAbs against cAg and eAg (e.g., refs. 9–13). Although the proteins have different termini, reflecting different postsynthetic processing (14), their epitopes have been assigned to their common core domain sequence (15) (Fig. 1a). There has been some debate as to whether there are one or two epitopes for cAg, but it is generally agreed that there are two epitopes for eAg: e1, which is conformational, and e2, which is linear (16). Enigmatically, the so-called “immunodominant loop” (11) has been implicated in both the cAg and e1 epitopes. e2 has been assigned to a sequence near the end of the core domain (15). In cAg capsids, e2 is cryptic, i.e., its epitope is inaccessible to antibodies. However, the full range of cAg epitope diversity has remained unclear as has the basis for the distinction between cAg and e1-Ag specificity. The situation has been complicated by difficulties implicit in mapping conformational epitopes by immunochemical methods.

Cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM) of immune complexes affords an incisive method of visualizing antigen–antibody interactions that has been fruitful in investigations of viral capsids (e.g., refs. 17 and 18). We have used this approach to localize the immunodominant loop, which is recognized as a linear epitope by mAb 312 (19), to the tip of the external spike (20). More recently, we found that conformational epitopes may be elucidated by cryo-EM analysis at 10- to 15-Å resolution (21), if the antigen's structure is known to high resolution, as is the case with HBV capsids (8). Exploiting the conservativity of IgG structure, generic Fabs taken from the Protein Data Bank (22) may be docked into the cryo-EM density map with high precision, making it possible to specify the point(s) of contact between antigen and antibody and thus identify the peptides that make up the epitope. In this way, mAb 3120 (23) was shown to bind to a discontinuous epitope that straddles the interface between subunits on adjacent dimers and does not involve the immunodominant loop (21). Here, we have used this approach to characterize the binding of two additional mAbs raised against HBV capsids. These observations reveal that the diversity of cAg epitopes is much greater than has been previously suspected, and they have implications for the basis of the distinction between core antigenicity and e-antigenicity.

Materials and Methods

Preparation of HBcAg Capsids. Capsids were prepared as described (5). Briefly, the core domain construct Cp149.3CA, in which the cysteines at positions 48, 61, and 107 are changed to alanines, was expressed in Escherichia coli and purified by gel filtration. Capsids were assembled from dimeric protein by adjusting the pH to 7.0 and the NaCl concentration to 350 mM. Dimers were obtained from the construct Cp149.3CA.G123A. This construct produces folded dimers that do not assemble into capsids (P.T.W. and S.J.S., unpublished results).

Generation of Fabs and Decoration of Capsids. mAb 3105 was purchased from the Institute of Immunology, Tokyo. mAb F11A4 was kindly provided by R. Tedder (University College, London). To produce Fab fragments, mAbs at 0.5 mg/ml were digested with immobilized ficin (Pierce) in 5 mM EDTA, 10 mM cysteine·HCl, 50 mM NaHPO4, pH 6.0 for 1.5 h at 37°C, and the resin was removed by centrifugal filtration. Fabs were mixed with capsids at an equimolar ratio of Fabs/monomers and examined by EM.

Cryo-EM. Data were collected as described (24). In brief, vitrified specimens suspended over holey carbon films were imaged at ×38,000 magnification with a CM200-FEG microscope (FEI, Eindhoven, The Netherlands) fitted with a Gatan 626 cryoholder, operating at 120 keV. Focal pairs of micrographs were recorded at ≈10 e–/Å2 per exposure. The first exposure was defocused such that the first zero of the contrast transfer function was at a frequency of (17 Å)–1 – (20 Å)–1. For the second exposure, the defocus was increased by 0.4 μm.

Image Reconstruction. Focal pairs of micrographs were digitized with a SCAI scanner (Z/I Imaging, Huntsville, AL), giving 7-μm pixels (1.8 Å at the specimen). Reconstructions were calculated as described (25), using the PFT algorithm (26) to determine orientations and origins, starting from preexisting maps of unlabeled Cp147 capsids: T = 4 (7) and T = 3 (5). The reconstructions included all particles with correlation coefficients of >0.5 for each of the three statistics calculated by PFT and were calculated to a spatial frequency limit of (11 Å)–1.

Molecular Modeling. These operations were performed essentially as described (21). In brief, dimers of capsid protein (Protein Data Bank ID code 1QGT) were first docked into unlabeled T = 4 and T = 3 capsids, and these dockings were then applied to the Fab-labeled reconstructions. In both steps, it was important to obtain consistent radial scaling. Thus the T = 4 unlabeled reconstruction was calibrated against a density map computed to 20-Å resolution from the crystal structure (8), as described (27–29). The scaling of the T = 3 capsid was thus assigned because it came from the same micrographs. The Fab-labeled reconstructions were scaled in the same way relative to unlabeled reconstructions. To dock the Fabs, initially a Fab (Protein Data Bank ID code 1FPT) was fitted manually into the corresponding portions of both the T = 4 and the T = 3 reconstructions. This process was done for both 3105 and F11A4. Latterly, the docking was done automatically with the antigen-binding domain of an IgG3 Fab (Protein Data Bank ID code 1CLZ) via the program colores (30). In situations where overlapping Fab densities or a locally low signal-to-noise ratio made the use of colores difficult, we relied on manual fitting. Density maps of Fablabeled capsids were computed from the modeled coordinates for various resolutions and temperature factors. Optimal values for these parameters were determined by comparing gray-level sections with those of the corresponding cryo-EM reconstructions (e.g., see Fig. 3).

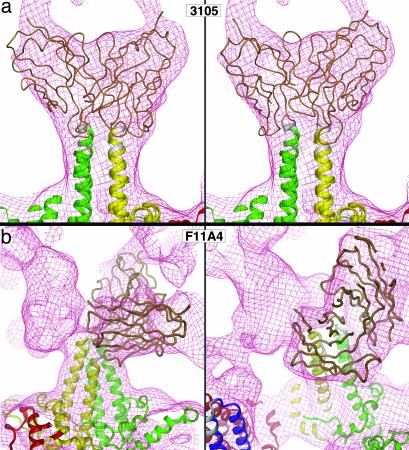

Fig. 3.

Central sections through cryo-EM density maps of Fab-labeled and control HBV capsids, viewed along a 2-fold symmetry axis. Protein density is dark. Axes of 5-, 3-, and 2-fold symmetry lie in this plane. Several axes and subunits are labeled in b. (Left and Center) Cryo-EM density maps calculated for the T = 3 capsid and T = 4 capsids labeled with Fab 3105 (a), control (b), and Fab F11A4 (c). Note that the Fab-associated density is lower than the capsid density, indicative of partial (≈50%) occupancy. (a and c Right) The corresponding simulations generated by docking atomic models of Fabs and the capsid protein into the cryo-EM maps of the labeled T = 4 capsid, and limiting the resulting models to the same resolution. (b Right) A surface rendering of the T = 4 capsid (protein is white) at higher magnification. The bisecting line shows the edge-on view of the T = 4 central sections as viewed from the left or right. (Bars = 50 Å.)

Results

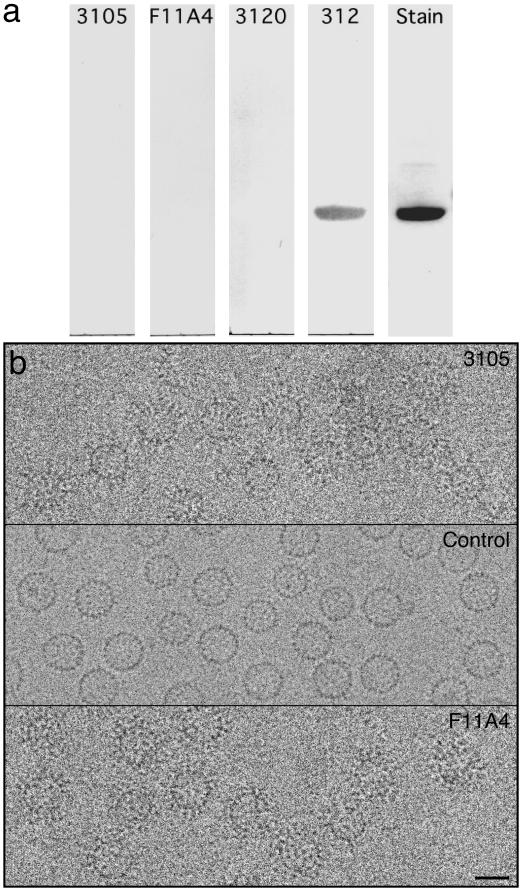

The immunogen used to generate mAb 3105, an IgG3, was HBV nucleocapsids isolated from enveloped virions (“Dane particles”) (23), whereas mAb F11A4, an IgG3b, was produced by using capsids obtained by expressing recombinant cAg in E. coli (31). We found both antibodies to be negative in Western blots (Fig. 2a), confirming that their epitopes are conformational. However, both bind to unassembled dimers as determined by a surface plasmon resonance assay (unpublished results) and to capsids (see below).

Fig. 2.

(a) The first four lanes show Western blots of HBV capsid protein detected with four anti-cAg mAbs. Negative results were recorded with mAbs 3105, F11A4, and 3120, all of which recognize conformational epitopes. mAb 312, which recognizes a linear epitope (19), afforded a positive control. The fifth lane shows a Coomassie blue-stained lane. (b) Cryo-micrographs of HBV capsids labeled with Fab 3105 (Top); control, no Fabs (Middle); and Fab F11A4 (Bottom). (Bar = 250 Å.)

For immunolabeling experiments, capsids were prepared by expressing a core domain construct in E. coli, isolating the capsids, dissociating them, further purifying the protein, and reassembling capsids. Fab fragments were prepared from both antibodies and incubated with capsids at an equimolar ratio of Fabs/capsid protein monomers. After ascertaining by negative staining that both Fabs bind to capsids, cryo-micrographs were recorded (Fig. 2b).

3D density maps were calculated for both labeling experiments (Fig. 3). The numbers of particles analyzed and the resolutions attained are summarized in Table 1. Because these preparations contained a majority of T = 4 capsids, these density maps were statistically better defined. The T = 3 reconstructions, based on fewer data, were somewhat noisier but still conveyed well the binding of both Fabs.

Table 1. Summary of image reconstructions of Fab-labeled HBV capsids.

| Antibody | Fab 3105 | Fab F11A4 | ||

| Micrographs | 15 defocus pairs | 4 defocus pairs | ||

| Map | T = 4 | T = 3 | T = 4 | T = 3 |

| Particles used/picked | 1,436/2,488 | 853/1,369 | 616/1,141 | 417/650 |

| Resolution* | 11.1 | 11.5 | 12.3 | 12.5 |

According to the Fourier shell correlation (FSC) criterion, with a threshold of 0.3. The FSC curves are shown in Fig. 7, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site, www.pnas.org.

Interaction of Fab 3105 with Capsids. Central sections through the density maps of labeled and control capsids are presented in Fig. 3. These sections are particularly informative because they contain longitudinal and transverse sections through dimers and because all three icosahedral symmetry axes (5-, 3-, and 2-fold) lie in this plane (Fig. 3b). Binding of Fab 3105 correlates with an additional plume of density rising radially outward from each spike (compare Fig. 3 a and b). The amounts of density associated with the A–B spike and the C–D spike are similar, and these densities are ≈2-fold symmetric about the dyad axis that passes through the center of each spike. Because no such symmetrization was imposed in calculating the density map and this symmetry is not intrinsic to the structure of a Fab molecule, we infer that it arose through averaging of Fabs bound to the two epitopes on opposite sides of the dyad axis. There is only enough space at the tip of a spike for one Fab to bind, whereupon it occludes the other epitope. Taken together, these observations imply that all four quasi-equivalent variants of this epitope on the T = 4 capsid (two on the A–B spike and two on the C–D spike) have essentially the same binding affinity. On average, they are ≈50% occupied and there are ≈120 Fabs per T = 4 capsid. Similar conclusions were reached from examining the density map of the T = 3 capsid decorated with Fab 3105 (Fig. 3a Left).

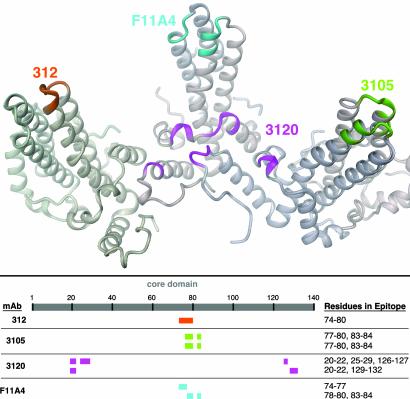

To identify the epitope, we docked atomic models of Fab molecules into our cryo-EM density maps of the labeled capsids after first placing in them high-resolution models of the capsid protein dimers. The Fabs were docked both manually, using a molecular graphics program (32), and with an automated procedure (30). The two approaches yielded consistent results. A good fit was achieved (Fig. 4), with the caveat that a Fab monomer would not be expected to dovetail exactly into the Fab-associated density that is artificially symmetrized (see above). As a byproduct of this exercise, it became apparent that there is near-maximal overlap between the two symmetryrelated Fab positions per spike. In overlapping situations of this kind, goodness-of-fit is best assessed by comparing the observed cryo-EM density map with models that represent an average over partial occupancy of both competing sites (compare Fig. 3a Center and Right). We conclude from this analysis that a bound Fab 3105 engages the immunodominant loops on both subunits, and that residues 77–80 and 83–84 are involved on both loops (Figs. 4a and 5).

Fig. 4.

(a) Models of the interaction of Fab 3105 with the spike on the T = 4 HBV capsid. The red wire-mesh envelope represents the cryo-EM density map of the Fab-labeled capsid. Left and Right represent a Fab (variable domain) bound, respectively, to the two epitopes that lie on either side of the dyad axis of the A–B dimer of capsid protein. In both binding modes, the Fab engages the immunodominant loops of both subunits. (b) Models of the interaction of Fab F11A4 with the A–B spike on the T = 4 capsid. The epitope is located to one side of the spike tip, where it has a major interaction with the immunodominant loop of one subunit [on the A subunit (green) in this illustration] and the outer portion of helix α4 and a minor interaction with the immunodominant loop of the other subunit (B subunit, yellow). Although it is a tight fit, two Fabs may bind to both epitopes presented on a single spike.

Fig. 5.

Summary mapping of the epitopes of four monoclonal anti-cAg IgGs. (Upper) The configurations of peptides involved in each case are marked on a ribbon diagram of three adjacent dimers. The epitope for mAb 3120 involves five peptides from two different subunits on neighboring dimers: on the T = 4 capsid, only two of four variants of the epitope (C–D and A–A) bind the Fab; on the T = 3 capsid, only one of three variants (A–A) bind it (21). mAbs 3105 and F11A4 each have contributions from both subunits within a dimer. mAb 312 binds primarily to the immunodominant loop on a single subunit. (Lower) The positions of these peptides on the core domain sequence are mapped.

Interaction of Fab F11A4 with Capsids. The binding of this Fab was modeled in similar fashion. It also attaches near the spike tip but, unlike 3105, which binds directly over the top of the spike, the F11A4 epitope is to one side (Figs. 3c and 4b) and its binding aspect is such that it appears possible for two Fabs to bind to the same spike (Fig. 3c; Fig. 4b Left). However, the occupancy was only ≈50% to judge by the average Fab-related density being about half that of capsid protein (compare Fig. 3c), i.e., ≈120 Fabs bound per T = 4 capsid. It transpires that once a Fab binds to a given spike, it occludes the epitope on a neighboring spike (see Fig. 3c), so that the maximum binding is limited to half of the sites being occupied.

The absence of overlap between Fabs at adjacent sites facilitated the docking experiments to identify this epitope (Fig. 4b). They reveal that F11A4 interacts with both subunits in a given dimer. The epitope is marked on a dimer in Fig. 5. On the left subunit, the Fab interacts with residues 74–77 where that immunodominant loop emerges from helix α3 (see ref. 8 for designation of the α-helical segments). On the other subunit, it interacts with residues 78–80 and 83–84 on the outer surface of the top two turns of helix α4 and the last residue in the loop. The conformational nature of this epitope reflects not only the requirement to have the two subunits appropriately juxtaposed, but also for the helices to be correctly folded.

Discussion

Immunoglobulins are large molecules, and a Fab is a bulky probe on the scale of the finest topographic features of proteins. In general, there may be motifs that are surface-exposed but sequestered in crevices. A case in point is the “canyon hypothesis” (33) whereby rhinovirus receptor binding sites were envisaged to reside at the bottom of a trench that is too narrow to be fully penetrated by an antibody, thus relieving this site from immunological pressure to evolve (but see ref. 34). In other contexts, steric blocking may serve as a regulatory device, e.g., in tropomyosin-mediated activation of muscular contraction (35), and the control of sequential protein–protein interactions in virus assembly (36, 37). In the case of HBV capsids, there is no evidence that steric blocking constraints on the binding of antibodies have a physiological role, but, as described below, they strongly influence multiple binding of any given antibody and simultaneous binding of different antibodies.

Steric Interference: Complications for Epitope Mapping by Cryo-EM. The small size of the repeating unit on the HBV capsid surface invokes strong interference effects. Once bound, a Fab will in most cases occlude a neighboring copy (or copies) of the same epitope. In consequence, in a cryo-EM reconstruction of fully labeled capsids, the added density will have the shape, not of a unitary Fab molecule but of an amalgam of Fabs bound to both (all) mutually interfering sites. Such was the case with Fab 3105 for which the two competing sites per spike overlap, and the molecular envelopes of Fabs bound at these sites overlap almost completely (Fig. 4a). Nevertheless, we were able to characterize the epitope by docking one Fab into this common volume and then confirming that the resulting model obtained with 50% occupancy of both competing sites matched well with the cryo-EM data (compare Fig. 3). We expect that most such epitopes may be determined in this way, starting from the Fab footprint as reference point and adjusting the Fabs' positions to optimize the match between the modeled density and the experimental density.

The binding of F11A4 was also substoichiometric but for a different reason. In this case, two Fabs may bind to a single spike but their tails occlude sites on neighboring spikes. In the reconstruction, each of the four quasi-equivalent variants of this epitope had ≈50% occupancy (Fig. 3c). We infer that all four variants have similar affinities for the Fab, and they are, on average, randomly occupied to a maximum complement of ≈120 molecules per T = 4 capsid.

Steric Interference: Implications for Epitope Mapping by Competition Experiments. Steric blocking also has important effects on the outcome of capsid-binding competitions between different anti-cAg antibodies. In most cases, full binding of one Fab will block access of a second Fab to any other site. Intact IgGs pose an even greater impediment. By modeling, we estimate that only ≈60 molecules of either 3105 or F11A4 can bind per T = 4 capsid (see Supporting Text and Fig. 6, which are published as supporting information on the PNAS web site).

There are a few exceptions to this trend of mutual exclusion: a Fab like 3105 that extends radially outward from the tip of the spike would not block another Fab from binding around the symmetry axes; and quasi-equivalent reductions in binding affinity, as are observed with Fab 3120 (21), may leave bare patches large enough for other antibodies to bind. Nevertheless, most bindings of one Fab exclude a second (different) Fab, and competition assays essentially amount to trials between the respective binding affinities, i.e., assuming that antibody-antigen binding is a dynamic equilibrium, challenge with a tighterbinding Fab should gradually displace the original Fab.

Thus almost any pair of anti-cAg mAbs is expected to compete, even though the epitopes in question may be widely separated on the capsid surface and the polypeptide chain. Conversely, the observation that two anti-cAg mAbs compete does not imply that they have the same epitope, nor that their epitopes overlap, nor even that the two epitopes are close together.

Diversity of cAg Epitopes. In general, any exposed surface of a protein antigen may present epitopes. This expectation is borne out in the case of hen egg white lysozyme whose interactions with five Fabs have been characterized (38). Together they cover more than half of the molecular surface and four of them do not overlap. At first sight, it is paradoxical that cAg capsids, although much larger than lysozyme, 4 MDa and 30 nm diameter vs. 30 kDa and 3–4 nm diameter, should present fewer opportunities for epitopes. This state of affairs is partly explained by the 60-fold redundancy of icosahedral symmetry and the inner surface being out of bounds to antibodies, but the array of spikes on the outer surface also imposes a major barrier. They restrict the access of antibodies to two regions, the spike and the areas around the symmetry axes (ref. 8 and unpublished results).

The four cAg epitopes characterized to date are mapped on capsid protein dimers in Fig. 5. One is on the region around the symmetry axes and three are located on spikes. All three of the latter epitopes involve the immunodominant loop: for the linear epitope 312, as a single copy; for the two conformational epitopes, 3105 and F11A4, with both loops per spike participating. Although the same peptide features in all three epitopes, it interacts with the respective Fabs in quite different ways and combinations. Thus although these epitopes are close together, indeed overlapping, they are distinct as evidenced by their structures (Fig. 5), the entirely different binding aspects of their cognate Fabs (Fig. 4a), and their respective binding affinities (unpublished results).

It is noteworthy that all three conformational epitopes bridge interfaces between adjacent subunits: in two cases (3105 and F11A4), across the dimer interface; with 3120, between adjacent dimers. This property explains their discontinuous character. Of the three, only 3120 exhibits quasi-equivalent variations in binding affinity, suggesting that there is more play in the interdimer interactions than in the intradimer interactions.

To return to the question of how many distinct cAg epitopes there are, the capsid has two areas where antibodies may bind. Both of them present epitopes and there is a pronounced heterogeneity of epitopes in the spike region that is likely to be repeated in the region around the symmetry axes. Thus the total number is likely to be considerably larger than four, although their reactivities will not, in general, be distinguished by competition assays.

e-Antigenicity and c-Antigenicity. The observation that the immunodominant loop is involved in both the cAg and e1-Ag epitopes (15) compounded the difficulty of explaining the distinction between them. There are two aspects to this dilemma. How does one short segment of polypeptide generate distinct antigenic specificities? And how is their noncrossreactivity to be explained, because the residues in question are located at the tip of the spike and should be accessible to antibodies on both capsids (cAg) and unassembled capsid protein (eAg)? The present observations cast light on the first question in demonstrating that the two copies of this motif that are juxtaposed at the spike tip, together with surrounding structural elements (e.g., helix α4 for F11A4), are capable of generating a considerable range of different conformational epitopes. mAbs 312, 3105, and F11A4 all bind to this region and would interfere strongly with each other's binding, but they differ markedly in their binding aspects and in the makeup of their epitopes. Thus it appears likely that cAg and e1-Ag antigenicity represent distinct epitopes (more likely, sets of epitopes) of this kind. Perhaps this distinction relates to their origins, cAg having been identified as eliciting a T cell-independent immune response and eAg, a T-cell-dependent response (39).

As to noncrossreactivity, current data point to some possibilities. First, not all anti-cAg antibodies bind to the spike tip. mAb 3120 binds to the interface between adjacent dimers and does not recognize unassembled protein (21). Anti-cAg Abs of this kind (15) would not recognize eAg. Conversely there are sites that are Fab-accessible on unassembled dimers, for instance, at the base of the spike or on its underside, that are inaccessible on capsids. Such sites could present eAg epitopes that would not crossreact with cAg. If they spanned the dimer interface, such epitopes could well be conformational. However, mAbs with this specificity have not been reported to date: in part this may reflect the fact that mAbs have been traditionally raised against particulate antigens (cAg capsids and Dane particles). Finally, we note that the binding of mAb 3120 is acutely sensitive to conformational effects involving small relative movements among the peptides that constitute the epitope (21). It is conceivable that similarly small shifts might affect the immunodominant loops and adjacent elements upon dimers switching between the assembled and unassembled states and contribute to the distinction between eand c-antigenicity. Further work is needed to distinguish among these alternatives.

Prospects for Immunodiagnosis. It has long been recognized that the relative preponderance of anti-cAg and anti-eAg antibodies in the serum of an infected individual serves as an indicator of the state of infection. Although it is not yet known which cAg epitopes predominate in infected humans, the foregoing analysis suggests that the range of anti-cAg antibodies developed in the course of an infection may be quite large. Accordingly, they have potential to provide more specific diagnostic tests. In this context, the screening of HBV patient sera at various stages postinfection against structurally defined cAgs and eAgs would be of interest. If different epitopes predominate at different stages of infection (40) or after initiation of a therapeutic regime (41), assays capable of distinguishing between them would be of value. In view of potential problems with steric interference (see above), assays involving antiidiotypic antibodies (42) appear promising because they would recognize antibodies present in serum, not cAg capsids per se.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. R. Tedder and B. Ferns for informative correspondence, Dr. B. Heymann for help with computing, and Dr. A. Harris for discussions.

Abbreviations: HBV, hepatitis B virus; cAg, core antigen; eAg, e-antigen; cryo-EM, cryo-electron microscopy.

References

- 1.Blumberg, B. S. (1997) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 94, 7121–7125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hollinger, F. B. (1996) in Fields Virology, eds. Fields, B. N., Knipe, D. M., Howley, P. M., Chanock, R. M., Melnick, J. L., Monath, T. P., Roizman, B. & Straus, S. E. (Lippincott–Raven, Philadelphia), pp. 2738–2808.

- 3.Cohen, B. J. & Richmond, J. E. (1982) Nature 296, 677–679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wingfield, P. T., Stahl, S. J., Williams, R. W. & Steven, A. C. (1995) Biochemistry 34, 4919–4932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Watts, N. R., Conway, J. F., Cheng, N., Stahl, S. J., Belnap, D. M., Steven, A. C. & Wingfield, P. T. (2002) EMBO J. 21, 876–884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bottcher, B., Wynne, S. A. & Crowther, R. A. (1997) Nature 386, 88–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Conway, J. F., Cheng, N., Zlotnick, A., Wingfield, P. T., Stahl, S. J. & Steven, A. C. (1997) Nature 386, 91–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wynne, S. A., Crowther, R. A. & Leslie, A. G. (1999) Mol. Cell 3, 771–780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ferns, R. B. & Tedder, R. S. (1984) J. Gen. Virol. 65, 899–908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sallberg, M., Norder, H. & Magnius, L. O. (1990) J. Med. Virol. 30, 1–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Salfeld, J., Pfaff, E., Noah, M. & Schaller, H. (1989) J. Virol. 63, 798–808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schodel, F., Moriarty, A. M., Peterson, D. L., Zheng, J. A., Hughes, J. L., Will, H., Leturcq, D. J., McGee, J. S. & Milich, D. R. (1992) J. Virol. 66, 106–114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pushko, P., Sallberg, M., Borisova, G., Ruden, U., Bichko, V., Wahren, B., Pumpens, P. & Magnius, L. (1994) Virology 202, 912–920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Standring, D. N., Ou, J. H., Masiarz, F. R. & Rutter, W. J. (1988) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 85, 8405–8409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Seifer, M. & Standring, D. N. (1995) Intervirology 38, 47–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sallberg, M., Pushko, P., Berzinsh, I., Bichko, V., Sillekens, P., Noah, M., Pumpens, P., Grens, E., Wahren, B. & Magnius, L. O. (1993) J. Gen. Virol. 74, 1335–1340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang, G. J., Porta, C., Chen, Z. G., Baker, T. S. & Johnson, J. E. (1992) Nature 355, 275–278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stewart, P. L. & Nemerow, G. R. (1997) Trends Microbiol. 5, 229–233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sallberg, M., Ruden, U., Magnius, L. O., Harthus, H. P., Noah, M. & Wahren, B. (1991) J. Med. Virol. 33, 248–252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Conway, J. F., Cheng, N., Zlotnick, A., Stahl, S. J., Wingfield, P. T., Belnap, D. M., Kanngiesser, U., Noah, M. & Steven, A. C. (1998) J. Mol. Biol. 279, 1111–1121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Conway, J. F., Watts, N. R., Belnap, D. M., Cheng, N., Stahl, S. J., Wingfield, P. T. & Steven, A. C. (2003) J. Virol. 77, 6466–6473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Berman, H. M., Westbrook, J., Feng, Z., Gilliland, G., Bhat, T. N., Weissig, H., Shindyalov, I. N. & Bourne, P. E. (2000) Nucleic Acids Res. 28, 235–242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Takahashi, K., Machida, A., Funatsu, G., Nomura, M., Usuda, S., Aoyagi, S., Tachibana, K., Miyamoto, H., Imai, M., Nakamura, T., et al. (1983) J. Immunol. 130, 2903–2907. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cheng, N., Conway, J. F., Watts, N. R., Hainfeld, J. F., Joshi, V., Powell, R. D., Stahl, S. J., Wingfield, P. E. & Steven, A. C. (1999) J. Struct. Biol. 127, 169–176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Conway, J. F. & Steven, A. C. (1999) J. Struct. Biol. 128, 106–118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Baker, T. S. & Cheng, R. H. (1996) J. Struct. Biol. 116, 120–130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Belnap, D. M., Grochulski, W. D., Olson, N. H. & Baker, T. S. (1993) Ultramicroscopy 48, 347–358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Belnap, D. M., Kumar, A., Folk, J. T., Smith, T. J. & Baker, T. S. (1999) J. Struct. Biol. 125, 166–175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Heymann, J. B. (2001) J. Struct. Biol. 133, 156–169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chacon, P. & Wriggers, W. (2002) J. Mol. Biol. 317, 375–384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ferns, R. B. & Tedder, R. S. (1986) J. Med. Virol. 19, 193–203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jones, T. A., Zou, J. Y., Cowan, S. W. & Kjeldgaard, M. (1991) Acta Crystallogr. A 47, 110–119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rossmann, M. G., He, Y. & Kuhn, R. J. (2002) Trends Microbiol. 10, 324–331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Smith, T. J., Chase, E. S., Schmidt, T. J., Olson, N. H. & Baker, T. S. (1996) Nature 383, 350–354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Parry, D. A. & Squire, J. M. (1973) J. Mol. Biol. 75, 33–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kellenberger, E. (1972) Ciba Found. Symp. 7, 189–206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Steven, A. C., Bauer, A. C., Bisher, M. E., Robey, F. A. & Black, L. W. (1991) J. Struct. Biol. 106, 221–236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Davies, D. R. & Cohen, G. H. (1996) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 93, 7–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Milich, D. R., McLachlan, A., Stahl, S., Wingfield, P., Thornton, G. B., Hughes, J. L. & Jones, J. E. (1988) J. Immunol. 141, 3617–3624. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tordjeman, M., Fontan, G., Rabillon, V., Martin, J., Trepo, C., Hoffenbach, A., Mabrouk, K., Sabatier, J. M., Van Rietschoten, J. & Somme, G. (1993) J. Med. Virol. 41, 221–229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Baumeister, M. A., Medina-Selby, A., Coit, D., Nguyen, S., George-Nascimento, C., Gyenes, A., Valenzuela, P., Kuo, G. & Chien, D. Y. (2000) J. Med. Virol. 60, 256–263. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Greenspan, N. S. & Bona, C. A. (1993) FASEB J. 7, 437–444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.