Abstract

Background

Primary intraocular lymphoma (PIOL) is a subset of primary central nervous system lymphoma (PCNSL) in which lymphoma cells initially invade the retina, vitreous, or optic nerve head, with or without concomitant CNS involvement. The incidence of this previously rare condition has increased dramatically. Given its nonspecific presentation and aggressive course, PIOL provides a diagnostic and therapeutic challenge.

Methods

We review the current strategies for diagnosis and treatment of PIOL and present our own experience with PIOL.

Results

Recent developments in the diagnosis of PIOL include immunohistochemistry, flow cytometry, cytokine evaluation, and molecular analysis. However, definitive diagnosis still requires harvesting of tissue for histopathology. Optimal treatment for PIOL remains unclear. Initial therapeutic regimens should include methotrexate-based chemotherapy and radiotherapy to the brain and eye. In addition, promising results have been seen with intravitreal methotrexate and autologous stem cell transplantation for recurrent and refractory disease.

Conclusions

Efforts to further determine the immunophenotype and molecular characteristics of PIOL will continue to assist in the diagnosis of PIOL. Future studies are required to determine the role of radiotherapy and optimal local and systemic chemotherapeutic regimens.

Introduction

Primary central nervous system lymphoma (PCNSL) is usually a diffuse large B-cell non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma that originates in the brain,spinal cord,leptomeninges,or eyes. PCNSL accounts for 4% to 6% of primary brain tumors and 1% to 2% of extranodal lymphomas.1 Primary intraocular lymphoma (PIOL) is a subset of PCNSL in which malignant lymphoid cells involve the retina, vitreous, or optic nerve head, with or without concomitant CNS involvement.2,3 This disease entity has also been referred to ocular reticulum cell sarcoma in older literature.4-6 In rare cases,PCNSL and PIOL may be an expression of T-cell lymphomas.7,8 Because PIOL remains confined to neural structures, it is distinguished from primary orbital lymphoma and systemic non-Hodgkin’s lymphomas that either involve or metastasize via the circulation to the uvea and ocular adnexa of the orbit, lacrimal gland, and conjunctiva.

While PIOL is a rare disease, its incidence over the past 15 years has risen, most likely due to the concomitant rise in PCNSL. The incidence of PCNSL has increased in both immunocompetent and immunocompromised people from 0.027/100,000 in 1973 to 1/100,000 in the early 1990s.9 While much of this rise can be accounted for by the increasing number of patients with immunodeficiencies, this does not completely account for the increase. The cause for the increased incidence in immunocompetent patients is unknown.10

The median age of onset of PCNSL/PIOL in immunocompetent patients is the late 50s and 60s, with a reported range of 15 to 85 years of age for PIOL.8 The male-female ratio is 1.2-1.7:1.9 Half of the patient population with PCNSL has multifocal disease at the time of initial presentation, with ocular involvement found in 15% to 25%.1,11 On the other hand, 60% to 80% of patients in whom PIOL is initially diagnosed develop CNS disease within a mean of 29 months.6,12,13 Ocular disease is bilateral in 80% of cases.6 This literature review provides an update of current diagnostic and treatment options for PIOL.

Diagnosis

Clinical Ophthalmic Diagnosis

PIOL commonly presents in older patients as a chronic uveitis masquerade syndrome that is unresponsive to therapy with corticosteroids. Patients often complain of blurred vision and floaters.8,12,14,15 Less common complaints include red eye, photophobia, and ocular pain.16-18 PIOL is one of a group of disorders that can present as intraocular inflammatory processes but are actually malignant diseases.2,13,19 Thus,the inflammation seen on clinical examination in these patients is a result of inflammation secondary to a primary disorder or represents noninflammatory cells and opacities.

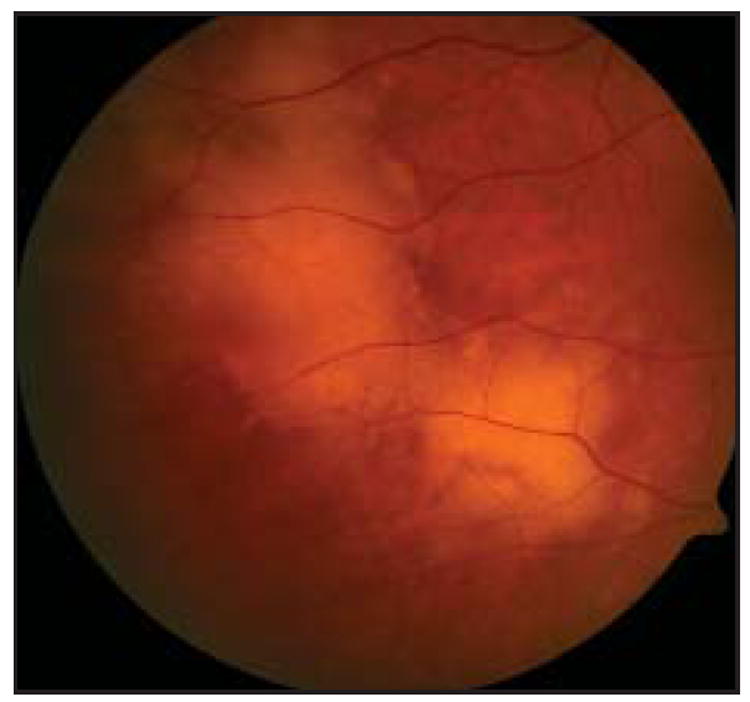

Visual acuity is often better than would be expected based on the clinical examination.12 The most common finding on ocular examination is vitreitis. The posterior segment examination usually reveals vitreous cells, which may form clumps or sheets.8,12,16,20,21 Between 50% to 75% of patients present with cells in the anterior chamber.8,22,23 In addition, examination of the fundus often reveals large, multifocal, cream- or yellow-colored subretinal infiltrates (Fig 1). If these lesions resolve, retinal pigment epithelium (RPE) atrophy and subretinal fibrosis may be evident as well.24

Fig 1.

Fundus photograph of a patient with PIOL showing yellow subretinal infiltrates that appear slightly hazy due to an overlying vitreitis.

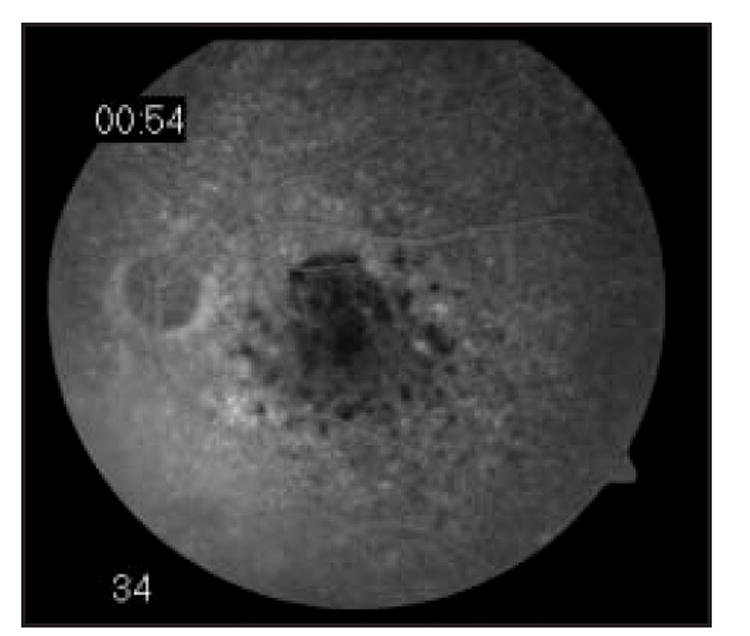

Several groups have studied angiographic findings in PIOL. In a series of 44 patients, Cassoux et al25 found punctate hyperfluorescent window defects in 54.5%, round hypofluorescent lesions in 34%, and vasculitis in 13.6%. At the National Eye Institute, a study of 17 patients with PIOL revealed that the most common findings were granularity, late staining, and blockage at the level of the RPE (Fig 2). Notably lacking were perivascular staining or leakage, macular edema, and other angiographic signs of inflammation.18

Fig 2.

Fluorescein angiogram of a patient with PIOL showing blockage that corresponds to tumor infiltrates.

Ultrasound may also be helpful in narrowing the diagnosis. Ultrasonographic findings in 13 patients with ocular lymphoma included vitreous debris (77%), choroidalscleral thickening (46%), widening of the optic nerve (31%), elevated chorioretinal lesions (23%), and retinal detachment (15%).26

Patients with CNS involvement may also present with general or focal neurological signs and symptoms. A review by Herrlinger et al27 found that the most common general symptoms were due to increased intracranial pressure (headache, nausea), seizures, and behavioral changes. The most common focal findings were hemiparesis, ataxia, and cranial nerve palsies.

Given the nonspecific nature of eye findings in PIOL, patients being considered for this diagnosis should be examined for other causes of uveitis,including sarcoidosis, intermediate uveitis,multifocal choroiditis,acute posterior multifocal placoid pigment epitheliopathy, birdshot chorioretinopathy, toxoplasmosis, ocular tuberculosis, and acute retinal necrosis.

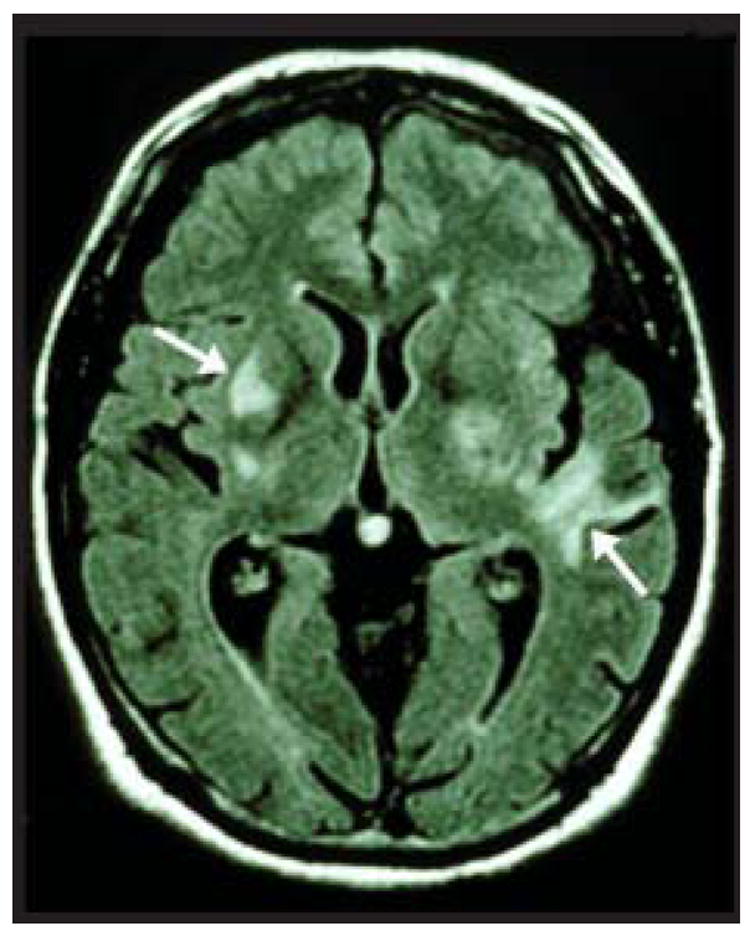

Neurological and Medical Diagnosis

A thorough medical and neurological examination is important, including a chest radiograph, complete blood cell count, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, routine blood chemistries, and other laboratory studies to exclude the aforementioned causes of uveitis. Because PIOL is closely related to PCNSL and seldom involves other organs, neuroimaging of the brain and orbits and a lumbar puncture are required.3,28,29 Computed topography (CT) scans usually reveal isodense or hyperdense lesions. Magnetic resonance imaging studies usually reveal lesions that are hypodense on T1-weighted and hypodense on T2-weighted images.11 Lesions are single at diagnosis in up to 70% of cases but are usually multifocal in late stages (Fig 3). The site of origin usually lies in the basal ganglia, corpus callosum, or periventricular subependymal regions.30 While imaging studies play an important role in the diagnosis of PCNSL, their role in the diagnosis of PIOL is more limited. Ocular imaging studies of 7 patients with biopsy proven PIOL revealed ocular findings in only 4 of the patients on T1-weighted CT and magnetic resonance images after contrast injection. Furthermore, these imaging modalities were not able to distinguish ocular lymphoma from other diseases such as uveitis or ocular melanoma.31

Fig 3.

Brain magnetic resonance imaging of a patient with PIOL showing multiple contrast-enhancing lesions (arrows).

Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) should be sent for routine cytologic, chemical, and cytokine analysis. Lymphoma cells can be identified in the CSF of 25% of patients with known lesions on magnetic resonance imaging.32 If lymphoma cells are found in the CSF, then a diagnosis of PCNSL can be made and no further diagnostic procedures are necessary to obtain an intraocular biopsy in a suspected eye. However, even if lymphoma cells are not found in the CSF, a stereotactic brain biopsy should be considered for patients who have suspicious brain lesions on neuroimaging studies.33 For patients with no evidence of disease by neuroimaging or CSF, a diagnostic vitrectomy should be performed on the eye with the most severe vitreitis or poorest visual acuity.21

Ocular Tissue Diagnosis

Cytology and Pathology

Diagnostic vitrectomy is the most common surgical procedure used to confirm a clinical impression of PIOL. Vitreous specimens should be handled with care to protect the often fragile lymphoma cells. The undiluted sample should be placed in 3 to 5 mL of cell culture medium and immediately brought to the cytology laboratory for rapid processing.12,34

Vitreous aspiration needle tap may also be used for diagnostic purposes. An advantage in this technique is that is can be completed in an outpatient setting without the need for monitored anesthesia. Lobo and Lightman35 recently reported 26 patients with suspected PIOL, 8 of whom were confirmed to have primary B- or T-cell intraocular lymphoma by this procedure. Two of these 8 patients required retinal biopsies in addition to the tap to confirm diagnosis,1 of whom had been treated with cyclosporine and oral prednisolone for 2 months prior to the tap. The remaining 18 patients were found to have infectious uveitis or nonspecific chronic inflammatory cells. The only complication noted in this procedure was a retinal detachment in one eye that developed 3 months after the procedure. Thus, this procedure may serve as a simpler mechanism to differentiate between infectious, malignant, and inflammatory causes of uveitis.

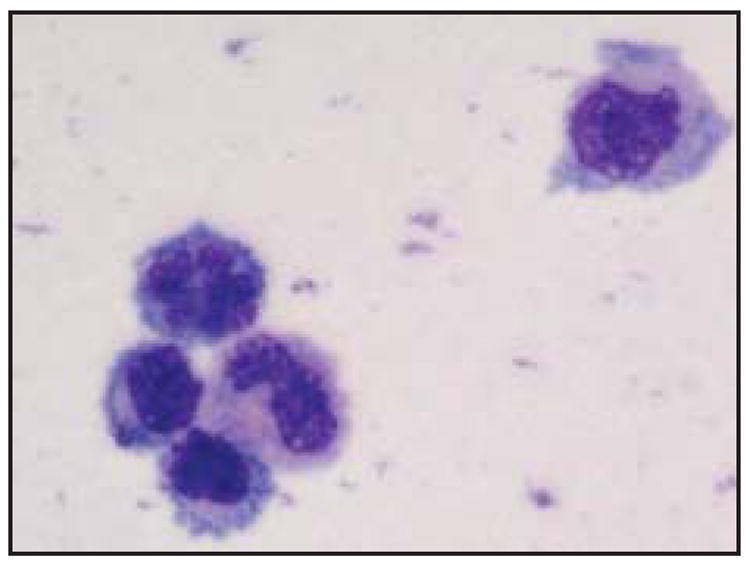

Malignant lymphoma cells found in vitreous fluid and CSF are usually large and pleomorphic with scanty basophilic cytoplasm (Fig 4).2,34 Other typical findings include hypersegmented round, oval, bean, or clover shaped nuclei with prominent nucleoli and multiple mitoses.12 However, the identification of malignant cells in vitrectomy samples is confounded by the presence of reactive immune cells, necrotic cells, debris, and fibrin.While CSF samples have less necrotic debris, they usually have few malignant cells.12,29

Fig 4.

Typical cytology of PIOL cells from the vitreous showing several atypical lymphoid cells with basophilic cytoplasm and large prominent irregular nuclei.

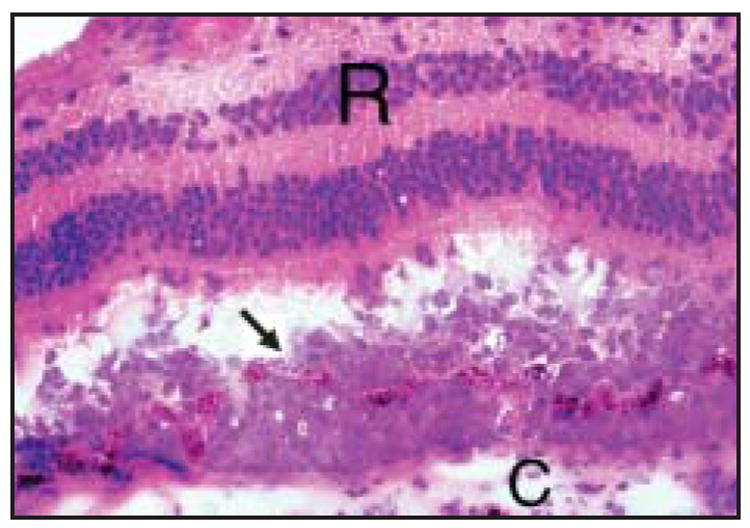

When attempts to obtain a vitrectomy specimen have been unsuccessful or no cells are evident in the specimen, chorioretinal biopsies may be considered.36 Chorioretinal biopsies can reveal a tumor cell infiltrate between the RPE and Bruch’s membrane (Fig 5), perivascular clumps of tumor cells in the retina and optic nerve head,diffuse infiltration in the vitreous, and hemorrhagic retinal necrosis. Chorioretinal biopsies may also reveal areas of retinal depigmentation, atrophy, and scarring due to RPE detachment and choroidal reactive lymphocytic infiltration.29,37 Fine-needle aspiration biopsy has been used in lieu of full thickness chorioretinal biopsy when vitrectomy was nondiagnostic. Lesions selected for this technique should be 1.5 mm or greater in height in order to prevent choroidal penetration. This technique has an advantage over vitrectomy of providing increased concentration of viable cells for cytopathologic diagnosis and molecular studies.38,39

Fig 5.

Histological examination of the eye showing tumor cells located between Bruch’s membrane and the RPE (arrow). The tumor cells have penetrated the RPE and are infiltrating towards the retina (R, retina; C, choroids; hematoxylin and eosin, × 400).

Because of the varying presentation of PIOL, diagnosis is often delayed 10 to 21 months, after a mean of 4.3 diagnostic procedures.8,12,15 Mishandling of vitreous specimens and prior treatment with corticosteroids at the time of vitrectomy, which are known to be cytolytic to lymphoma cells,12 can lower the diagnostic yield. A series of 12 cases at the National Eye Institute revealed that 30% of PIOL patients had previous false-negative biopsy specimens.12 When diagnostic vitreous aspiration, vitrectomy, needle biopsy,and chorioretinal biopsy have failed,diagnostic enucleation of a blinded eye could be considered.40,41

It is difficult to arrive at a pathologic diagnosis of PIOL.33,42 Thus, research has been focused on developing other methods to assist in the diagnosis of PIOL. These methods include immunohistochemistry, flow cytometry, molecular analysis, and cytokine evaluation.

Immunophenotyping and Flow Cytometry

Immunohistochemistry and flow cytometry rely on the finding that most PIOLs are monoclonal populations of B lymphocytes that stain for B-cell markers (CD19, CD20, CD22) and have restricted expression of kappa or lambda chains.12,34,40 Immunohistochemistry has also been used to demonstrate expression of BCL-6 and MUM1 in PIOL cells. BCL-6 is a B-cell marker that is normally turned off as B cells move from the germinal center into the marginal zone during B-cell differentiation.43 MUM1 is a protein involved in the control of plasma cell differentiation. While B cells usually only express one of these proteins at a time, concomitant expression of these proteins has been shown in systemic diffuse large B-cell lymphoma.44 Similar patterns of expression have also been demonstrated in 5 patients with PIOL.45

Several studies have demonstrated that flow cytometry may be a helpful addition in the diagnosis of PIOL. Flow cytometry allows for the analysis of several different markers simultaneously and has been used to confirm monoclonality in PIOL. Flow cytometry allows for the analysis of several different markers simultaneously and has been used to confirm monoclonality in PIOL. Immunophenotyping by flow cytometry was found to be diagnostic of PIOL in 6 of 10 patients, whereas cytology was only positive in 7 of 12 patients.15 In addition, flow cytometry identified intraocular lymphoma in 7 of 10 patients compared with only 3 diagnosed by cytology.46 However, other studies have found cytologic evaluation to be more accurate.42 It is still believed that a pathologic diagnosis is required to confirm the presence of PIOL and that immunophenotyping plays a supportive role in diagnosis.

Molecular Analysis

Microdissection and polymerase chain reaction have become useful adjuncts in the diagnosis of PIOL. These techniques allow for selection of a relatively pure cell population from frozen or paraffin-embedded archival tissues.47 Studies of systemic non-Hodgkin’s lymphomas have revealed amplification of rearranged heavy chain immunoglobulin (IgH) gene sequences, particularly in the third complementarity-determining region (CDR3) of the IgH variable region.48,49 Likewise, ocular specimens from patients with PIOL have revealed similar IgH rearrangements that can serve as a molecular marker of clonal expansion of lymphocytes.47 Using primers in microdissection and PCR studies, it was found that in 57 PIOL samples,100% expressed the IgH gene rearrangement at the CDR3 site.50 Monoclonality of B-cell populations has also been characterized with the use of FR3,FR2,and CDR3 primers and polymorphism analysis.47,51

Microdissection and PCR analysis have also been used to examine the expression of a translocation between the genes for IgH and Bcl-2. Bcl-2, a gene involved in the regulation of apoptosis,is located on chromosome 18,while IgH is located on chromosome 14. 52 The t(14;18) translocation brings the Bcl-2 gene under the control of the IgH promoter, thus deregulating the Bcl-2 gene and resulting in Bcl-2 expression.53 This translocation is found in 85% of follicular non-Hodgkin’s lymphomas and 28% of diffuse large B-cell lymphomas.54,55 Sixty percent of Bcl-2 breakpoints are located at the major breakpoint region (Mbr) in the 3′ non-coding part of the third exon. The next most frequent location for translocations (10% to 25%) is the minor cluster region (mcr) located 20 kb downstream of the gene.55-57

Analyses performed on specimens from 69 patients with PIOL revealed that 37 (54%) expressed the t(14;18) translocation at the Mbr.47 We have recently detected that 15 (22%) of 68 patients with PIOL express the translocation at the mcr in addition to the translocation at the Mbr (D.J.W., unpublished data, 2004). Of these patients, 14 (93%) of 15 were also positive for the Mbr,indicating some overlap of the breakpoint regions, while 1 (7%) was positive only at the mcr. While the t(14;18) translocation is used as a marker for diagnosis and monitoring of follicular lymphoma, its role in prognosis and treatment selection for follicular lymphoma and diffuse large B-cell lymphoma remains unclear and is being investigated in clinical studies.58-62 Likewise, it will be important to determine the role of Bcl-2 expression in clinical presentation, treatment response, relapse rate, and survival in patients with PIOL.

Cytokines

Cytokines may play a role in distinguishing PIOL from uveitis. While interleukin 6 (IL-6) is produced in high levels by inflammatory cells in uveitis, IL-10 is produced by malignant B lymphocytes in intraocular and CNS lymphoma.63 Moreover, PIOL is strongly associated with an increased IL-10 to IL-6 ratio (greater than 1.0).63-65 This finding is supported by findings of 35 patients with PIOL and 64 patients with infectious and noninfectious uveitis where the 1.0 cutoff rule was correct 74.7% of the time (sensitivity 74.3%, specificity 75.0%).66 There have been previous reports of 2 patients with cytologically proven intraocular CNS lymphoma with a vitreous IL-10 to Il-6 ratio less than 1.0.37,67 However,one of these cases represented early-stage disease.37

Lymphoma cells express chemokine receptors selective for B cells such as CXCR4 and CXCR5. The RPE of involved eyes expresses the ligands for these receptors, SDF-1 (CXCL12) and BLC (CXCL13), respectively, thus suggesting a pathogenetic role for B-cell chemokines in the homing of lymphoma cells to the RPE.68

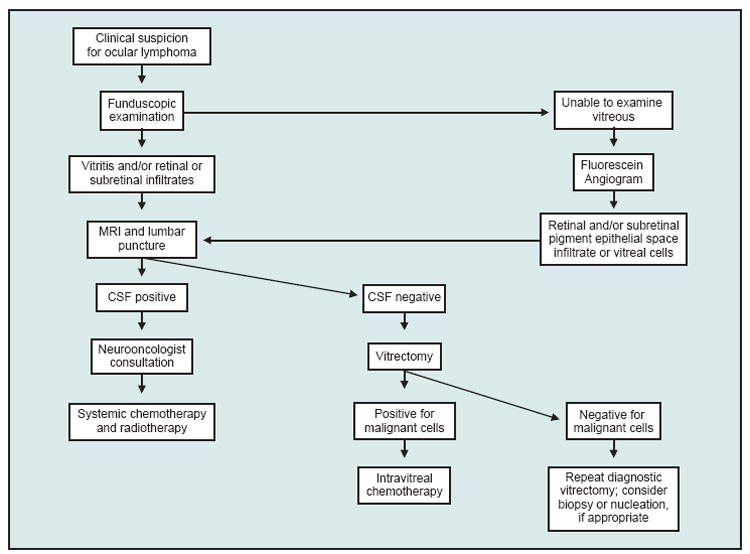

A diagnosis of PIOL should be considered for a patient older than 35 years of age with a history of posterior uveitis with the presence of vitreous cells in sheets and clumps on funduscopic examination or retinal lesions by fluorescein angiography. These patients should undergo neuroradiologic imaging and CSF examination. No further ocular diagnostic tests are required in patients with positive CSF. In patients with negative CSF, a vitrectomy or vitreous tap should be performed in the eye with more severe vitreitis or worse visual acuity. This sample should be carefully sent for cytology, cytokine analysis, IgH rearrangements, Bcl-2/IgH translocations, and immunohistochemistry/flow cytometry. Chorioretinal biopsies may be required when vitrectomy specimens are nondiagnostic. Fig 6 summarizes the diagnostic guideline used at the National Eye Institute. Since systemic symptoms are usually present at the time of diagnosis for patients with systemic lymphoma involving the eye, systemic evaluation, CT scans of the chest and abdomen, and bone marrow aspirate and biopsy are not usually performed unless systemic symptoms are present.69 Because of the cytolytic nature of corticosteroids on lymphoma cells, corticosteroid treatment should be withheld until all diagnostic procedures are completed.

Fig 6.

Algorithm for the diagnosis of PIOL.

Treatment

Historical Overview

The treatment of PCNSL and PIOL differs from the treatment of systemic lymphoma. Therapies that have proven effective for systemic lymphoma have not been successful in PCNSL and PIOL.70 In addition, resection, while usually applicable to brain tumors,does not play a role in the therapy of PCNSL.11 Whole-brain radiation was once the mainstay of PCNSL therapy. A prospective, multicenter, phase II trial examined whole-brain radiation (40 Gy with a 20-Gy boost to the tumor) in 41 patients with PCNSL. The response rate was a 90%, but 68% of patients relapsed. Median survival was only 11.6 months.71

It is generally believed that chemotherapy is the first line of treatment for PCNSL.11 High-dose methotrexate (MTX) should be included in all therapies, as it penetrates the blood-brain barrier and has a complete response rate of 50% to 80%.72 Chemotherapy and radiotherapy combination regimens increase median survival to 40 months, with almost 25% of patients surviving for 5 years or more.73 However,ocular disease recurs in 50% of cases. In addition, these results must be weighed against complications of delayed neurotoxic effects.74,75

Many issues are still unresolved, including the best MTX-based chemotherapy regimen, the role of chemotherapy-only treatments, the necessity of intrathecal chemotherapy, the role, dosage, and schedule of whole-brain radiotherapy, and the role of blood-brain barrier disruption.10,11,76,77

For intraocular lymphoma, radiotherapy was once the treatment of choice.6,78 For disease limited to the eye, radiotherapy alone (30 Gy to both eyes20,79) often led to a prolonged disease-free state.20 Ocular recurrences were common, and most patients developed CNS disease within 14 to 84 months.16,78 Furthermore, many side effects of radiation were observed, including cataract formation, radiation retinopathy,optic neuropathy,dry eye syndrome, and prolonged corneal epithelial defects.6,21,78 However, other case series have not noted any radiotherapy complications after follow-up of 24 to 140 months.16,20

The major difficulty with using chemotherapy to treat patients with ocular involvement is the blood-ocular barrier. This barrier results from tight junctions located between vascular endothelial cells and also between pigmented epithelial cells of the anterior uvea (blood-aqueous barrier) and the retina (blood-retinal barrier).80 However, MTX and cytosine arabinoside (Ara-C) are able to penetrate the blood-ocular barrier and have become mainstays of therapy.81

Current Trends

Systemic and Intrathecal Treatments

Several trials of systemic chemotherapy for intraocular disease have been conducted. A study of 9 patients examined a high-dose MTX schedule consisting of induction (8 g/m2 MTX every 14 days until complete response), consolidation (8 g/m2 MTX administered every 14 days for 2 doses), and maintenance (8 g/m2 MTX administered every 28 days for 11 doses).82 MTX levels 4 hours after infusion were higher than 1μm in both the vitreous and aqueous humors, indicating cytotoxic levels. The patient population included 7 patients with concurrent PCNSL and PIOL and 2 with isolated PIOL. Seven of the 9 patients had a response in the eye, while 2 of 9 had refractory eye disease and required orbital radiation that led to complete response. All 7 patients with disease in the brain had complete responses of their brain disease. Two patients died of CNS progression at 17 and 27 months, while 1 patient was lost to follow-up. The range of follow-up on the remaining 6 patients was varied, but they remained disease free from 8+ to 85+ months. While this study showed high MTX levels in the vitreous, the evidence of disease recurrence corroborates other studies’ findings that it may be difficult to maintain sufficient levels of MTX in the vitreous humor after intravenous infusion.83

Another trial of intravenous MTX (8 g/m2) in induction, maintenance, and consolidation phases in 5 patients with PCNSL with intraocular involvement showed complete response of brain lesions in 4 patients and partial response in 1.84 Four of the 5 patients with ocular symptoms responded.

Other systemic trials have been used with Ara-C,alone and in combination with MTX.81,85,86 Valluri et al86 used systemic chemotherapy consisting of MTX and high-dose Ara-C in 3 patients with PIOL (2 with concomitant CNS involvement). Both ocular and intracranial disease resolved, with remission for at least 24 months. A trial of Ara-C alone (2 to 3 g/m2) included 6 patients with intraocular lymphoma.85 Of the 6 patients, 4 were previously untreated, 1 had relapsed after radiation treatment, and 1 had received chemotherapy for systemic lymphoma. Five of the patients responded (1 complete and 4 partial).

Ocular complications from systemic MTX include periorbital edema, blepharitis, conjunctival hyperemia, increased lacrimation, and photophobia in up to 25% of patients. Complications of Ara-C include conjunctivitis, keratitis, and ocular irritation. Most of these side effects are reversible and may be treated with topical lubrications and topical corticosteroids.86

A study of 22 patients with PIOL (21 with CNS involvement) examined varying treatments of chemotherapy followed by radiotherapy in 13 patients, chemotherapy alone in 3 patients,and radiotherapy either alone or followed by chemotherapy in 5 patients.87 One patient was not treated. Chemotherapy combined with ocular irradiation resulted in better control of ocular disease. Median failure-free survival for the entire series was 10 months,with a 2-year failure-free survival rate of 34%. This study also noted that the detection of ocular relapse was associated with shorter survival at 2 years (12% vs 55%).

Intrathecal MTX may also play a role in treatment of PIOL. While intrathecal MTX alone was unable to reach detectable levels in the eye,88 a study of 2 patients with recurrent CNS and intraocular lymphoma showed successful treatment with intrathecal MTX and Ara-C.89 Intrathecal MTX may also be beneficial when combined with systemic chemotherapy regimens. A study of 14 patients with CNS disease (5 with ocular involvement) examined the role of chemotherapy alone including high-dose MTX (8.4 g/m2) with thiotepa, vincristine, dexamethasone, and intrathecal Ara-C and MTX.90 Three of the 5 patients with ocular disease had complete responses. Two patients with partial responses were treated with local treatment and had a complete response (1 with intravitreous chemotherapy and the other with local radiation). Overall survival and progression-free survival rates at 57 months of follow-up were 68.8% and 34.3%, respectively.

Stem-Cell Transplantation

Intensive chemotherapy followed by autologous stem-cell transplant was reported to rescue patients with refractory or recurrent PCNSL and PIOL.91,92 A study by Soussain et al91 of 22 patients with PCNSL included 11 patients with PIOL (3 with isolated ocular disease and 8 with concomitant CNS involvement). Five of the 8 patients with CNS disease had partial or complete response and had survival times of 18+ to 70+ months. One of these patients had systemic progression and died in 3 months. Two had ocular recurrences. One had complete response with subsequent ocular radiotherapy, while the other died due to a second tumor. Two of the 3 patients with isolated ocular disease had complete response, while the other patient with isolated ocular disease had intraocular lymphoma recurrence at 3 months and then died of a second tumor. While only 1 of the 11 patients with PIOL experienced neurotoxicity, 7 of the 22 total patients experienced this side effect. In addition, this treatment is not recommended for patients older than 60 years of age because 5 of 7 patients in this age group died of treatment complications.91 A study by Abrey et al92 included 2 patients with ocular disease but information about their follow-up was limited. The encouraging data from these two studies suggests that this therapeutic approach may be useful in difficult cases but certainly requires further evaluation.

Intravitreal Methotrexate

Radiotherapy alone was once used to treat patients with isolated ocular disease. Due to radiation complications and the fact that this treatment cannot be repeated if the patient relapses, intravitreal treatment has become more desirable for both isolated and recurrent ocular disease. As opposed to intravenous MTX, where cytotoxic levels are maintained only for several hours, intravitreal MTX is able to maintain therapeutic doses in the vitreous humor for 5 days.93 Intravitreal MTX was first attempted on 4 patients (7 eyes) as an adjunctive treatment to radiation and enhanced chemotherapy using blood-brain barrier disruption by intra-arterial mannitol.94 All 4 patients had remission of eye disease, with follow-up ranging from 9 to 19 months.

Another trial of intravitreal MTX involved an induction phase of twice weekly intravitreal MTX (400μg) for 1 month, followed by weekly consolidation injections for 1 month,followed by monthly injections for 1 year in 26 eyes of 16 patients.95 Eight of these patients initially had brain involvement, while 8 presented with ocular involvement. Follow-up ranged from 6 to 35 months, with a median of 18.5 months. While 4 eyes were cleared of tumor after a diagnostic vitrectomy, the remaining eyes were free of malignant cells after 12 injections. Disease recurred in 3 patients (6 eyes), but all achieved remission after a repeat course of intravitreal MTX. The most common complications were cataract, corneal epitheliopathy, and maculopathy. Less common complications were limbal stem cell damage, optic atrophy, and sterile endophthalmitis.

Intravitreal MTX may also play a role in the treatment of recurrent intraocular lymphoma. A patient with recurrent intraocular lymphoma after radiotherapy and repeated systemic chemotherapeutic regiments was treated with repeated intravitreal injections of MTX and thiotepa, leading to eradication of the tumor for at least 156 days.93 While intravitreal MTX avoids systemic toxicity and can provide consistent therapeutic drug concentrations, it will not treat lesions in the CNS or other eye.

The optimal method of treatment of PIOL or PCNSL with ocular involvement is yet to be determined. Developing a consensus on the appropriate treatment is difficult due to the rarity of these malignancies. The literature is abundant with small case series that make comparing treatment regimens difficult (Table). Furthermore, large, randomized clinical trials comparing the efficacy of radiation and chemotherapy to chemotherapy alone are neither feasible nor ethical. In addition, the results of PCNSL trials are difficult to extrapolate to PIOL.

TABLE. Summary of Therapeutic Options for Initial and Recurrent Primary Intraocular Lymphoma (PIOL).

| Treatment Options | Regimen | References |

|---|---|---|

| Initial PIOL | ||

| Chemotherapy Alone: | ||

| High-dose MTX | 8 g/m2 induction (q14d until response), consolidation (2 doses q14d), and maintenance (11 doses q28d) | Soussain et al96 1996 Batchelor et al82 2003 Batchelor et al84 2003 |

| High-dose Ara-C | 2-3 g/m2* × 3 months for 6 cycles | Strauchen et al85 1989 |

| Multiagent regimens | ESHAP: cisplatin 100 mg/m2 in 96 hrs, VP-16 40 mg/m2 daily d1-d4, Ara-C 2 g/m2 d5, and methylprednisolone 500 mg daily d1-d4 ** | Soussain et al96 1996 |

| Systemic and intrathecal chemotherapy | Thiotepa 35 mg/m2, vincristine 1.4 mg/m2, MTX 8.4 g/m2, dexamethasone 4 mg/d in 21 days, and intrathecal Ara-C 50 mg and MTX 12 mg or intrathecal Ara-C 15 mg *** | Sandor et al90 1998 |

| Chemotherapy and Radiotherapy: | ||

| Systemic/intrathecal chemotherapy and radiotherapy | Chemotherapy regimens included methylprednisolone, high-dose MTX (intravenous and intrathecal), Ara-C, thiotepa, cisplatin, VP-16 (intravenous and intrathecal), vincristine, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, procarbazine, CCNU, dexamethasone, etoposide; ESHAP (see above) | Peterson et al16 1993 Valluri et al86 1995 Soussain et al96 1996 Cassoux et al25 2000 Ferreri et al87 2002 |

| Whole-brain and ocular radiation: 20-60 Gy in 8-28 fractions | Hoffman et al8 2003 | |

|

| ||

| Refractory or Recurrent PIOL | ||

| Chemotherapy Alone: | ||

| Intravitreal MTX | MTX 0.4 mg induction (biweekly until response), consolidation (1 dose/wk for 1 mo) and maintenance (monthly for 1 yr) | Fishburne et al94 1997 Smith et al95 2002 |

| Intravitreal MTX and thiotepa | MTX 0.4 mg and thiotepa 2 mg | de Smet et al93 1999 |

| Intrathecal MTX and Ara-C | No dosages provided | Mason et al89 2003 |

| Combined Regimens: | ||

| High-dose chemotherapy and stem cell rescue | Thiotepa 250 mg/m2 daily × 3, busulfan total of 10 mg/kg over 3 days, and cyclophosphamide 60 mg/kg daily ×2 followed by hematopoietic stem cell rescue | Soussain et al91 2001 |

| MTX (3.5 g/m2 ×5 cycles) and Ara-C (3 g/m2× 2d for 2 cycles) followed by carmustine 300 mg/m2, etoposide 100 mg/m2, cytarabine 200 mg/m2, and melphalan 140 mg/m2 followed by autologous stem cell rescue (PCNSL patients, 2 of whom had eye involvement) | Abrey et al92 2003 | |

MTX = methotrexate

Ara-C = cytarabine

Included 2 patients with recurrent disease.

4 of 7 patients also received high-dose MTX (5 mg/m2).

Included 1 patient with recurrent disease.

The current consensus on the treatment of PCNSL with eye involvement is systemic high-dose MTX-based chemotherapy with radiation to the globes.3 Isolated eye disease should be treated similarly,although complications from radiation and promising results with systemic high-dose MTX regimens may indicate that the latter is a better choice. Recurrence of intraocular lymphoma alone should be treated with intravitreal MTX. Future studies are needed to determine the optimal high-dose MTX-based chemotherapy regimens, the role of radiation, and the role of intravitreal MTX in initial disease presentation. Future therapeutic regimens may also include rituximab, a monoclonal antibody against CD20, which has been shown to have activity in systemic lymphoma.97-99 Due to poor penetration of blood-brain barrier,rituximab will likely require intrathecal and intravitreal administration in the treatment of PCNSL and PIOL.100-102

Conclusions

PIOL is a subset of PCNSL that presents initially in the eye with no involvement of the brain, spinal cord, meninges, or CSF, although future CNS involvement is likely to occur. The diagnosis should be considered in middle-aged to elderly patients who develop prolonged intraocular inflammation that fails to respond to immunosuppressive treatment (so-called uveitis masquerade syndrome). Workup includes neuroimaging, lumbar puncture with CSF cytology and, if needed, diagnostic vitrectomy or ocular tissue biopsy. Measurement of intraocular cytokine levels and detection of immunoglobulin gene rearrangements in lymphoma cells may facilitate the diagnosis.

The optimal treatment of PIOL is yet to be determined and requires collaboration between the ophthalmologist and a neurooncologist. While the prognosis of this disease remains poor, current research efforts aimed at early diagnosis and emerging treatment modalities may help to improve survival. In addition, new data on the possible role of infectious agents in B-cell transformation, such as human herpesvirus 8, Epstein-Barr virus, and Toxoplasma gondii could some day lead to prevention.50

Abbreviations used in this paper

- CSF

cerebrospinal fluid

- IgH

heavy chain immunoglobulin

- Mbr

major breakpoint region

- mcr

minor cluster region

- MTX

methotrexate

- PCNSL

primary central nervous system lymphoma

- PIOL

primary intraocular lymphoma

- RPE

retinal pigment epithelium

Footnotes

No significant relationship exists between the authors and the companies/organizations whose products or services may be referenced in this article.

References

- 1.Hochberg FH, Miller DC. Primary central nervous system lymphoma. J Neurosurg. 1988;68:835–853. doi: 10.3171/jns.1988.68.6.0835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chan CC, Buggage RR, Nussenblatt RB. Intraocular Lymphoma. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2002;13:411–418. doi: 10.1097/00055735-200212000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hormigo A, DeAngelis LM. Primary ocular lymphoma: clinical features, diagnosis, and treatment. Clin Lymphoma. 2003;4:22–29. doi: 10.3816/clm.2003.n.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Appen RE. Posterior uveitis and primary cerebral reticulum cell sarcoma. Arch Ophthalmol. 1975;93:123–124. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1975.01010020129006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Volcker HE, Naumann GO. “Primary” reticulum cell sarcoma of the retina. Dev Ophthalmol. 1981;2:114–120. doi: 10.1159/000395312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Freeman LN, Schachat AP, Knox DL, et al. Clinical features, laboratory investigations, and survival in ocular reticulum cell sarcoma. Ophthalmology. 1987;94:1631–1639. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(87)33256-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Paulus W. Classification, pathogenesis, and molecular pathology of primary CNS lymphomas. J Neurooncol. 1999;43:203–208. doi: 10.1023/a:1006242116122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hoffman PM, McKelvie P, Hall AJ, et al. Intraocular lymphoma: a series of 14 patients with clinicopathological features and treatment outcomes. Eye. 2003;17:513–521. doi: 10.1038/sj.eye.6700378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schabet M. Epidemiology of primary CNS lymphoma. J Neurooncol. 1999;43:199–201. doi: 10.1023/a:1006290032052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nasir S, DeAngelis LM. Update on the management of primary CNS lymphoma. Oncology (Huntingt) 2000;14:228–234. discussion 37-242, 244. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.DeAngelis LM. Brain tumors. N Engl J Med. 2001;344:114–123. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200101113440207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Whitcup SM, de Smet MD, Rubin BI, et al. Intraocular lymphoma.Clinical and histopathologic diagnosis. Ophthalmology. 1993;100:1399–1406. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(93)31469-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Akpek EK, Ahmed I, Hochberg FH, et al. Intraocular-central nervous system lymphoma: clinical features,diagnosis,and outcomes. Ophthalmology. 1999;106:1805–1810. doi: 10.1016/S0161-6420(99)90341-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Read RW, Zamir E, Rao NA. Neoplastic masquerade syndromes. Surv Ophthalmol. 2002;47:81–124. doi: 10.1016/s0039-6257(01)00305-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rothova A, Ooijman F, Kerkhoff F, et al. Uveitis masquerade syndromes. Ophthalmology. 2001;108:386–399. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(00)00499-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Peterson K, Gordon KB, Heinemann MH, et al. The clinical spectrum of ocular lymphoma. Cancer. 1993;72:843–849. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19930801)72:3<843::aid-cncr2820720333>3.0.co;2-#. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gill MK, Jampol LM. Variations in the presentation of primary intraocular lymphoma: case reports and a review. Surv Ophthalmol. 2001;45:463–471. doi: 10.1016/s0039-6257(01)00217-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Velez G, Chan CC, Csaky KG. Fluorescein angiographic findings in primary intraocular lymphoma. Retina. 2002;22:37–43. doi: 10.1097/00006982-200202000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nussenblatt RB, Whitcup SM, Palestine AG. In: Uveitis: Fundamentals and Clinical Practice. 2. Louis St., editor. Mo: Mosby; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Char DH, Ljung BM, Miller T, et al. Primary intraocular lymphoma (ocular reticulum cell sarcoma) diagnosis and management. Ophthalmology. 1988;95:625–630. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(88)33145-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Buggage RR, Chan CC, Nussenblatt RB. Ocular manifestations of central nervous system lymphoma. Curr Opin Oncol. 2001;13:137–142. doi: 10.1097/00001622-200105000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bardenstein DS. Intraocular lymphoma. Cancer Control. 1998;5:317–325. doi: 10.1177/107327489800500403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Velez G, de Smet MD, Whitcup SM, et al. Iris involvement in primary intraocular lymphoma: report of two cases and review of the literature. Surv Ophthalmol. 2000;44:518–526. doi: 10.1016/s0039-6257(00)00118-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dean JM, Novak MA, Chan CC, et al. Tumor detachments of the retinal pigment epithelium in ocular/central nervous system lymphoma. Retina. 1996;16:47–56. doi: 10.1097/00006982-199616010-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cassoux N, Merle-Beral H, Leblond V, et al. Ocular and central nervous system lymphoma: clinical features and diagnosis. Ocul Immunol Inflamm. 2000;8:243–250. doi: 10.1076/ocii.8.4.243.6463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ursea R, Heinemann MH, Silverman RH, et al. Ophthalmic, ultrasonographic findings in primary central nervous system lymphoma with ocular involvement. Retina. 1997;17:118–123. doi: 10.1097/00006982-199703000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Herrlinger U, Schabet M, Bitzer M, et al. Primary central nervous system lymphoma: from clinical presentation to diagnosis. J Neurooncol. 1999;43:219–226. doi: 10.1023/a:1006298201101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bataille B, Delwail V, Menet E, et al. Primary intracerebral malignant lymphoma: report of 248 cases. J Neurosurg. 2000;92:261–266. doi: 10.3171/jns.2000.92.2.0261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tuaillon N, Chan CC. Molecular analysis of primary central nervous system and primary intraocular lymphomas. Curr Mol Med. 2001;1:259–272. doi: 10.2174/1566524013363915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Basso U, Brandes AA. Diagnostic advances and new trends for the treatment of primary central nervous system lymphoma. Eur J Cancer. 2002;38:1298–1312. doi: 10.1016/s0959-8049(02)00031-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kuker W, Herrlinger U, Gronewaller E, et al. Ocular manifestation of primary nervous system lymphoma: what can be expected from imaging? J Neurol. 2002;249:1713–1716. doi: 10.1007/s00415-002-0919-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.DeAngelis LM. Primary central nervous system lymphoma. Curr Opin Neurol. 1999;12:687–691. doi: 10.1097/00019052-199912000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Blumenkranz MS, Ward T, Murphy S, et al. Applications and limitations of vitreoretinal biopsy techniques in intraocular large cell lymphoma. Retina. 1992;12:S64–S70. doi: 10.1097/00006982-199212031-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Davis JL, Solomon D, Nussenblatt RB, et al. Immunocytochemical staining of vitreous cells.Indications, techniques, and results. Ophthalmology. 1992;99:250–256. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(92)31984-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lobo A, Lightman S. Vitreous aspiration needle tap in the diagnosis of intraocular inflammation. Ophthalmology. 2003;110:595–599. doi: 10.1016/S0161-6420(02)01895-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kirmani MH, Thomas EL, Rao NA, et al. Intraocular reticulum cell sarcoma: diagnosis by choroidal biopsy. Br J Ophthalmol. 1987;71:748–752. doi: 10.1136/bjo.71.10.748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Buggage RR, Velez G, Myers-Powell B, et al. Primary intraocular lymphoma with a low interleukin 10 to interleukin 6 ratio and heterogeneous IgH gene rearrangement. Arch Ophthalmol. 1999;117:1239–1242. doi: 10.1001/archopht.117.9.1239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Levy-Clarke GA, Byrnes GA, Buggage RR, et al. Primary intraocular lymphoma diagnosed by fine needle aspiration biopsy of a subretinal lesion. Retina. 2001;21:281–284. doi: 10.1097/00006982-200106000-00023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fyrat P, Mocan G. Lymphoma presenting as a solitary mass: diagnosis by fine needle aspiration biopsy. Cytopathology. 2000;11:276–278. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2303.2000.00236.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lopez JS, Chan CC, Burnier M, et al. Immunohistochemistry findings in primary intraocular lymphoma. Am J Ophthalmol. 1991;112:472–474. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(14)76269-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Matzkin DC, Slamovits TL, Rosenbaum PS. Simultaneous intraocular and orbital non-Hodgkin lymphoma in the acquired immune deficiency syndrome. Ophthalmology. 1994;101:850–855. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(94)31248-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Char DH, Ljung BM, Deschenes J, et al. Intraocular lymphoma: immunological and cytological analysis. Br J Ophthalmol. 1988;72:905–911. doi: 10.1136/bjo.72.12.905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Harris NL, Stein H, Coupland SE, et al. New approaches to lymphoma diagnosis. Hematology (Am Soc Hematol Educ Program) 2001:194–220. doi: 10.1182/asheducation-2001.1.194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Falini B, Fizzotti M, Pucciarini A, et al. A monoclonal antibody (MUM1p) detects expression of the MUM1/IRF4 protein in a subset of germinal center B cells, plasma cells, and activated T cells. Blood. 2000;95:2084–2092. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Coupland SE, Bechrakis NE, Anastassiou G, et al. Evaluation of vitrectomy specimens and chorioretinal biopsies in the diagnosis of primary intraocular lymphoma in patients with Masquerade syndrome. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2003;241:860–870. doi: 10.1007/s00417-003-0749-y. Epub 2003 Sep 30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Davis JL, Viciana AL, Ruiz P. Diagnosis of intraocular lymphoma by flow cytometry. Am J Ophthalmol. 1997;124:362–372. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(14)70828-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Shen DF, Zhuang Z, LeHoang P, et al. Utility of microdissection and polymerase chain reaction for the detection of immunoglobulin gene rearrangement and translocation in primary intraocular lymphoma. Ophthalmology. 1998;105:1664–1669. doi: 10.1016/S0161-6420(98)99036-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chen YT, Whitney KD, Chen Y. Clonality analysis of B-cell lymphoma in fresh-frozen and paraffin-embedded tissues: the effects of variable polymerase chain reaction parameters. Mod Pathol. 1994;7:429–434. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Abdel-Reheim FA, Edwards E, Arber DA. Utility of a rapid polymerase chain reaction panel for the detection of molecular changes in B-cell lymphoma. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 1996;120:357–363. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Chan CC. Molecular pathology of primary intraocular lymphomas. Trans Am Ophthalmol Soc. 2003;101:275–292. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Gorochov G, Parizot C, Bodaghi B, et al. Characterization of vitreous B-cell infiltrates in patients with primary ocular lymphoma, using CDR3 size polymorphism analysis of antibody transcripts. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2003;44:5235–5241. doi: 10.1167/iovs.03-0035. Erratum in: Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2004 45:367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hockenbery D, Nunez G, Milliman C, et al. Bcl-2 is an inner mitochondrial membrane protein that blocks programmed cell death. Nature. 1990;348:334–336. doi: 10.1038/348334a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ngan BY, Chen-Levy Z, Weiss LM, et al. Expression in non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma of the bcl-2 protein associated with the t(14;18) chromosomal translocation. N Engl J Med. 1988;318:1638–1644. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198806233182502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Yunis JJ, Oken MM, Kaplan ME, et al. Distinctive chromosomal abnormalities in histologic subtypes of non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. N Engl J Med. 1982;307:1231–1236. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198211113072002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Weiss LM, Warnke RA, Sklar J, et al. Molecular analysis of the t(14;18) chromosomal translocation in malignant lymphomas. N Engl J Med. 1987;317:1185–1189. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198711053171904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Cotter F, Price C, Zucca E, et al. Direct sequence analysis of the 14q+ and 18q- chromosome junctions in follicular lymphoma. Blood. 1990;76:131–135. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Cleary ML, Galili N, Sklar J. Detection of a second t(14;18) breakpoint cluster region in human follicular lymphomas. J Exp Med. 1986;164:315–320. doi: 10.1084/jem.164.1.315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Barrans SL, Evans PA, O’Connor SJ, et al. The t(14;18) is associated with germinal center-derived diffuse large B-cell lymphoma and is a strong predictor of outcome. Clin Cancer Res. 2003;9:2133–2139. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Barrans SL, Carter I, Owen RG, et al. Germinal center phenotype and bcl-2 expression combined with the International Prognostic Index improves patient risk stratification in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Blood. 2002;99:1136–1143. doi: 10.1182/blood.v99.4.1136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Buchonnet G, Jardin F, Jean N, et al. Distribution of BCL2 breakpoints in follicular lymphoma and correlation with clinical features: specific subtypes or same disease? Leukemia. 2002;16:1852–1856. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2402568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kramer MH, Hermans J, Wijburg E, et al. Clinical relevance of BCL2, BCL6, and MYC rearrangements in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Blood. 1998;92:3152–3162. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Lopez-Guillermo A, Cabanillas F, McDonnell TI, et al. Correlation of bcl-2 rearrangement with clinical characteristics and outcome in indolent follicular lymphoma. Blood. 1999;93:3081–3087. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Chan CC, Whitcup SM, Solomon D, et al. Interleukin-10 in the vitreous of patients with primary intraocular lymphoma. Am J Ophthalmol. 1995;120:671–673. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(14)72217-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Whitcup SM, Stark-Vancs V, Wittes RE, et al. Association of interleukin 10 in the vitreous and cerebrospinal fluid and primary central nervous system lymphoma. Arch Ophthalmol. 1997;115:1157–1160. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1997.01100160327010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Cassoux N, Merle-Beral H, LeHoang P, et al. Interleukin-10 and intraocular-central nervous system lymphoma. Ophthalmology. 2001;108:426–427. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(00)00401-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Wolf LA, Reed GF, Buggage RR, et al. Vitreous cytokine levels. Ophthalmology. 2003;110:1671–1672. doi: 10.1016/S0161-6420(03)00811-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Akpek EK, Maca SM, Christen WG, et al. Elevated vitreous interleukin-10 level is not diagnostic of intraocular-central nervous system lymphoma. Ophthalmology. 1999;106:2291–2295. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(99)90528-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Chan CC, Shen D, Hackett JJ, et al. Expression of chemokine receptors, CXCR4 and CXCR5, and chemokines, BLC and SDF-1, in the eyes of patients with primary intraocular lymphoma. Ophthalmology. 2003;110:421–426. doi: 10.1016/S0161-6420(02)01737-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Qualman SJ, Mendelsohn G, Mann RB, et al. Intraocular lymphomas. Natural history based on a clinicopathologic study of eight cases and review of the literature. Cancer. 1983;52:878–886. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19830901)52:5<878::aid-cncr2820520523>3.0.co;2-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.O’Neill BP, O’Fallon JR, Earle JD, et al. Primary central nervous system non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma: survival advantages with combined initial therapy? Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1995;33:663–673. doi: 10.1016/0360-3016(95)00207-F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Nelson DF, Martz KL, Bonner H, et al. Non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma of the brain: can high dose, large volume radiation therapy improve survival? Report on a prospective trial by the Radiation Therapy Oncology Group (RTOG): RTOG 8315. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1992;23:9–17. doi: 10.1016/0360-3016(92)90538-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.DeAngelis LM. Primary CNS lymphoma: treatment with combined chemotherapy and radiotherapy. J Neurooncol. 1999;43:249–257. doi: 10.1023/a:1006258619757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.DeAngelis LM, Yahalom J, Thaler HT, et al. Combined modality therapy for primary CNS lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 1992;10:635–643. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1992.10.4.635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.DeAngelis LM, Seiferheld W, Schold SC, et al. Combination chemotherapy and radiotherapy for primary central nervous system lymphoma: Radiation Therapy Oncology Group Study 93-10. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20:4643–4648. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Abrey LE, DeAngelis LM, Yahalom J. Long-term survival in primary CNS lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 1998;16:859–863. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1998.16.3.859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Ferreri AJ, Abrey LE, Blay JY, et al. Summary statement of primary central nervous system lymphomas from the Eighth International Conference on Malignant Lymphoma, Lugano, Switzerland, June 12 to 15, 2002. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:2407–2414. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.01.135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Khan RB, Shi W, Thaler HT, et al. Is intrathecal methotrexate necessary in the treatment of primary CNS lymphoma? J Neurooncol. 2002;58:175–178. doi: 10.1023/a:1016077907952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Margolis L, Fraser R, Lichter A, et al. The role of radiation therapy in the management of ocular reticulum cell sarcoma. Cancer. 1980;45:688–692. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19800215)45:4<688::aid-cncr2820450412>3.0.co;2-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Siegel MJ, Dalton J, Friedman AH, et al. Ten-year experience with primary ocular “reticulum cell sarcoma” (large cell non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma) Br J Ophthalmol. 1989;73:342–346. doi: 10.1136/bjo.73.5.342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Cunha-Vaz J. The blood-ocular barriers. Surv Ophthalmol. 1979;23:279–296. doi: 10.1016/0039-6257(79)90158-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Baumann MA, Ritch PS, Hande KR, et al. Treatment of intraocular lymphoma with high-dose Ara-C. Cancer. 1986;57:1273–1275. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19860401)57:7<1273::aid-cncr2820570702>3.0.co;2-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Batchelor TT, Kolak G, Ciordia R, et al. High-dose methotrexate for intraocular lymphoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2003;9:711–715. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Henson JW, Yang J, Batchelor T. Intraocular methotrexate level after high-dose intravenous infusion. J Clin Oncol. 1999;17:1329. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Batchelor T, Carson K, O’Neill A, et al. Treatment of primary CNS lymphoma with methotrexate and deferred radiotherapy: a report of NABTT 96-07. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:1044–1049. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.03.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Strauchen JA, Dalton J, Friedman AH. Chemotherapy in the management of intraocular lymphoma. Cancer. 1989;63:1918–1921. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19890515)63:10<1918::aid-cncr2820631008>3.0.co;2-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Valluri S, Moorthy RS, Khan A, et al. Combination treatment of intraocular lymphoma. Retina. 1995;15:125–129. doi: 10.1097/00006982-199515020-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Ferreri AJ, Blay JY, Reni M, et al. Relevance of intraocular involvement in the management of primary central nervous system lymphomas. Ann Oncol. 2002;13:531–538. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdf080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.de Smet MD, Stark-Vancs V, Kohler DR, et al. Intraocular levels of methotrexate after intravenous administration. Am J Ophthalmol. 1996;121:442–444. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(14)70444-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Mason JO, Fischer DH. Intrathecal chemotherapy for recurrent central nervous system intraocular lymphoma. Ophthalmology. 2003;110:1241–1244. doi: 10.1016/S0161-6420(03)00268-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Sandor V, Stark-Vancs V, Pearson D, et al. Phase II trial of chemotherapy alone for primary CNS and intraocular lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 1998;16:3000–3006. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1998.16.9.3000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Soussain C, Suzan F, Hoang-Xuan K, et al. Results of intensive chemotherapy followed by hematopoietic stem-cell rescue in 22 patients with refractory or recurrent primary CNS lymphoma or intraocular lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19:742–749. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2001.19.3.742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Abrey LE, Moskowitz CH, Mason WP, et al. Intensive methotrexate and cytarabine followed by high-dose chemotherapy with autologous stem-cell rescue in patients with newly diagnosed primary CNS lymphoma: an intent-to-treat analysis. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:4151–4156. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.05.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.de Smet MD, Vancs VS, Kohler D, et al. Intravitreal chemotherapy for the treatment of recurrent intraocular lymphoma. Br J Ophthalmol. 1999;83:448–451. doi: 10.1136/bjo.83.4.448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Fishburne BC, Wilson DJ, Rosenbaum JT, et al. Intravitreal methotrexate as an adjunctive treatment of intraocular lymphoma. Arch Ophthalmol. 1997;115:1152–1156. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1997.01100160322009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Smith JR, Rosenbaum JT, Wilson DJ, et al. Role of intravitreal methotrexate in the management of primary central nervous system lymphoma with ocular involvement. Ophthalmology. 2002;109:1709–1716. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(02)01125-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Soussain C, Merle-Beral H, Reux I, et al. A single-center study of 11 patients with intraocular lymphoma treated with conventional chemotherapy followed by high-dose chemotherapy and autologous bone marrow transplantation in 5 cases. Leuk Lymphoma. 1996;23:339–345. doi: 10.3109/10428199609054837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Maloney DG. Rituximab for follicular lymphoma. Curr Hematol Rep. 2003;2:13–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Avivi I, Robinson S, Goldstone A. Clinical use of rituximab in haematological malignancies. Br J Cancer. 2003;89:1389–1394. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6601187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Hanel M, Fiedler F, Thorns C. Anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody (Rituximab) and Cidofovir as successful treatment of an EBV-associated lymphoma with CNS involvement. Onkologie. 2001;24:491–494. doi: 10.1159/000055132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Pels H, Schulz H, Schlegel U, et al. Treatment of CNS lymphoma with the anti-CD20 antibody rituximab: experience with two cases and review of the literature. Onkologie. 2003;26:351–354. doi: 10.1159/000072095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Feugier P, Virion JM, Tilly H, et al. Incidence and risk factors for central nervous system occurrence in elderly patients with diffuse large-B-cell lymphoma: influence of rituximab. Ann Oncol. 2004;15:129–133. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdh013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Rubenstein JL, Combs D, Rosenberg J, et al. Rituximab therapy for CNS lymphomas: targeting the leptomeningeal compartment. Blood. 2003;101:466–468. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-06-1636. Epub 2002 Sep 5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]