Abstract

Ehlers-Danlos syndrome type IV, the vascular type of Ehlers-Danlos syndromes (EDS), is an inherited connective tissue disorder defined by characteristic facial features (acrogeria) in most patients, translucent skin with highly visible subcutaneous vessels on the trunk and lower back, easy bruising, and severe arterial, digestive and uterine complications, which are rarely, if at all, observed in the other forms of EDS. The estimated prevalence for all EDS varies between 1/10,000 and 1/25,000, EDS type IV representing approximately 5 to 10% of cases. The vascular complications may affect all anatomical areas, with a tendency toward arteries of large and medium diameter. Dissections of the vertebral arteries and the carotids in their extra- and intra-cranial segments (carotid-cavernous fistulae) are typical. There is a high risk of recurrent colonic perforations. Pregnancy increases the likelihood of a uterine or vascular rupture. EDS type IV is inherited as an autosomal dominant trait that is caused by mutations in the COL3A1 gene coding for type III procollagen. Diagnosis is based on clinical signs, non-invasive imaging, and the identification of a mutation of the COL3A1 gene. In childhood, coagulation disorders and Silverman's syndrome are the main differential diagnoses; in adulthood, the differential diagnosis includes other Ehlers-Danlos syndromes, Marfan syndrome and Loeys-Dietz syndrome. Prenatal diagnosis can be considered in families where the mutation is known. Choriocentesis or amniocentesis, however, may entail risk for the pregnant woman. In the absence of specific treatment for EDS type IV, medical intervention should be focused on symptomatic treatment and prophylactic measures. Arterial, digestive or uterine complications require immediate hospitalisation, observation in an intensive care unit. Invasive imaging techniques are contraindicated. Conservative approach is usually recommended when caring for a vascular complication in a patient suffering from EDS type IV. Surgery may, however, be required urgently to treat potentially fatal complications.

Disease name and synonyms

Ehlers-Danlos syndrome type IV

Sack-Barabas syndrome

Vascular Ehlers-Danlos syndrome

Vascular type of Ehlers-Danlos syndromes (EDS)

Definition

Ehlers-Danlos syndrome type IV, also known as the vascular type of Ehlers-Danlos syndromes (EDS), is an inherited disorder of connective tissue characterised by severe arterial and digestive complications which are rarely, if at all, observed in the other forms EDS [1,2]. Patients with EDS type IV, most of whom display characteristic facial features and premature ageing of limb extremities (acrogeria), are predisposed to vascular and digestive ruptures, as well as perforations of the gravid uterus. Arterial ruptures account for the majority of deaths, whilst digestive perforations, occurring mainly on the sigmoid colon, are less often fatal. These complications, rare in childhood, affect 25% of patients before the age of 20, and 80% by the age of 40 [1]. The median age of death is estimated to be 50 years. Due to different clinical symptoms, natural history and prognosis, EDS type IV should be assessed separately within the group of EDS.

Epidemiology

The Ehlers-Danlos syndromes are a group of hereditary disorders of connective tissue, whose prevalence is estimated between 1/10,000 and 1/25,000, with no ethnic predisposition. The Villefranche classification identifies six clinical types (Table 1) [3], among which the vascular EDS (OMIM #130050) accounts for about 5 to10% of cases [4].

Table 1.

Classification of Ehlers-Danlos syndromes

| Type | Former nosology | OMIM # | Inheritance | Gene and locus | References |

| Classical type | Type I | 130000 | ADa |

COL5A1, 9q34 COL5A2, 17q21 Other? |

[59, 60] |

| Classical type | Type II | 130010 | AD |

COL5A1, 9q34 COL5A217q21 Other? |

[59, 60] |

| Ehlers-Danlos like syndrome with Tenascin X deficiency | 606408 | ARb | TNXB, 6p21.3 | [61] [62] | |

| Hypermobility type | Type III | 130020 | AD |

TNXB, 6p21.3 Other? |

[63] |

| Vascular type | Type VIA Type VIB |

225400 | AR |

PLOD, 1p36 ? |

[64] |

| Arthrochalasia type | Types VIIA and VIIB | 130060 | AD |

COL1A1, 17q21 COL1A2, 7q22 |

[65] [66] |

| Dermatosparaxis type | Type VIIC | 225410 | AR | ADAMTS2, 5q23 | [67] |

| Progeroid type | 130070 | AD | XGPT1, 5q35 | [68] | |

| Periodontitis type | Type VIII | 130080 | AD | ?, 12p13 | [69] |

| Ehlers-Danlos variant with periventricular heterotopia | 300537 | XLc | FLNA, Xq28 | [70] |

aAD: Autosomal dominant

bAR: Autosomal resessive

cXL: X-linked

Clinical presentation

Clinical diagnosis of vascular Ehlers-Danlos syndrome is based on four criteria: a characteristic facial aspect (acrogeria) in most patients, thin and translucent skin with highly visible subcutaneous vessels, ecchymoses and haematomas, and arterial, digestive and obstetrical complications.

A. Facial dysmorphy

When present, acrogeria is defined by characteristic facial features such an emaciated face with prominent cheekbones and sunken cheeks. The eyes appear sunken or bulging, often with colouring around them and thin telangiectasia on the eyelids [5]. The nose is pinched and thin, as are the lips, particularly the upper lip whose edges are undefined [5]. A non-acrogeric form of the syndrome may also exist, whose clinical diagnosis is more difficult as several distinguishing features are not present [6].

B. Skin symptoms

In vascular EDS, the skin is abnormally thin and pale. It is smooth, soft and velvety. The veins under the skin are distinctly visible as the skin is translucent on the thorax, the shoulders and, sometimes, the abdomen. The skin on the extremities appears prematurely aged, hence the term acrogeria, and the subcutaneous veins are highly visible. We have recently shown that anteflexion of the trunk during clinical examination reveals highly visible subcutaneous vessels on the lower back. In our experience, this sign has proved highly valuable in establishing the clinical diagnosis [Germain DP, unpublished data].

However, there is no hyperelasticity of the skin in EDS type IV, in contrast to classical EDS (types I and II) and hypermobile EDS (type III) [7]. Fragility of the skin may be observed, though less often than in classical EDS. This leads to wounds with an abnormally long scarring process. Secondary enlargement of scars and deposits of residual haemosiderin are typical.

C. Ecchymoses and haematomas

Ecchymoses and haematomas are common [6] and extensive bruising (Figure 1) is one of the major diagnostic criteria in the Villefranche nosology of Ehlers-Danlos syndromes [3].

Figure 1.

Extensive bruising of the legs in a child affected with Ehlers-Danlos syndrome type IV.

D. Complications

Patients suffering from vascular EDS are prone to arterial, digestive and obstetrical complications.

1) Vascular complications

The exact nature of the vascular lesions is disputed in the literature, as most of these correspond to arterial dissections or tears caused by the deterioration of congenitally thin and fragile tissue, leading to haematomas, false aneurysms or intracavitary bleeding. Most of the aneurysms recorded in the literature are probably 'false aneurysms', even though a percentage of patients display real fusiform aneurysms [8]. Arterial ruptures or dissections are responsible for the majority of deaths as they are unpredictable [9] and because the fragility of arterial walls often makes the surgical repair difficult [10-13].

All anatomical areas can be affected, with a tendency toward arteries of large and medium calibre [14]. The disease frequently involves the proximal branches of the aortic arch, the descending thoracic aorta and the abdominal aorta. The distal branches of the aorta, especially the renal, mesenteric, iliac and femoral arteries, are also particularly affected [10,15-17].

Dissections of the vertebral arteries and the carotids in their extra- and intra-cranial segments have been widely documented and are a typical complication of the syndrome (Figures 2, 3) [18-20]. Carotid-cavernous fistulae (CCF) are another typical complication of EDS type IV [21,22] due to reduced content of collagen III in the arterial walls. CCF clinical diagnosis is based on the existence of tinnitus, thrill, headaches and pulsating exophthalmos [16,18,19].

Figure 2.

Angio-MRI (coronal section) of the supra-aortic vessels after injection of 20 cc of gadolinium in a woman aged 24 with EDS type IV, revealing a dissecting haematoma of the left internal carotid (black arrow), a bilateral dissection of the vertebral arteries in their V1 and V2 segments (white arrows) and a dissection of the middle and distal third of the right subclavian artery (head of arrow).

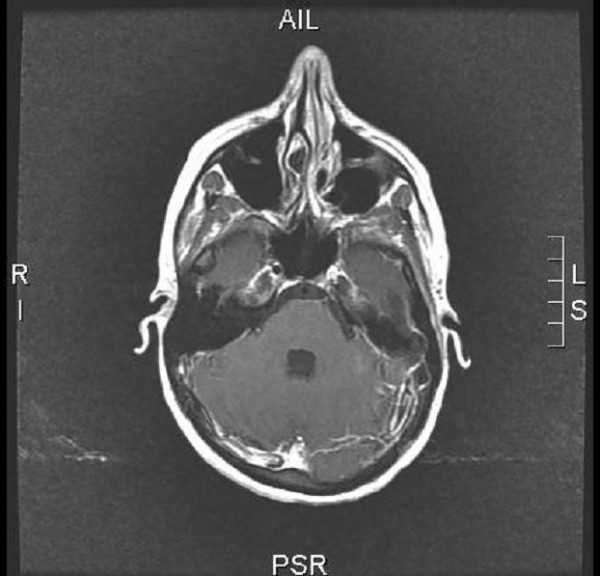

Figure 3.

Cerebral angio-MRI after injection of 20 cc of gadolinium in a woman aged 24 with EDS type IV displaying a dissecting haematoma of the left internal carotid.

EDS type IV should therefore be considered after any ischemic stroke in young subject [5,23]. In addition, intracranial haemorrhages are found in 4% of cases, half of which are caused by the rupture of a previously-identified intracranial aneurysm [20]. This prevalence appears higher than in the general population, where the frequency of unruptured aneurysms is estimated between 0.5 and 1% [19]. Early diagnosis of brain haemorrhage in patients with EDS type IV is important, as it has significant implications for the care of patients and their relatives. In patients with confirmed diagnosis of vascular EDS, non-invasive techniques (echo-Doppler, angioscan, angio-MRI) are absolutely imperative for diagnosing arterial dissections or aneurysms [24]. Arteriograms are associated with a high rate of complications at the point of puncture and/or tear of the arterial wall and are thus contraindicated [25]. The benefit/risk ratio of any invasive diagnostic procedure should be carefully assessed and arteriogram reserved only for cases where arterial embolisation is planned [24]. If thrombosis occurs after carotid or vertebral dissection, anticoagulation may be required but should be carried out with care. Surgical treatment of brain aneurysms has a high morbidity mortality rate owing to the brittle nature of the tissue in these patients. Endovascular radiology treatments also have a high post-treatment morbidity and mortality [22,24].

The low instance of cerebrovascular complications does not work in favour of systematic scanning for brain aneurysms in asymptomatic patients suffering from EDS type IV, in whom the risks linked to surgery often contraindicate surgery before the appearance of symptoms [19].

There is some controversy about the usefulness of serial vascular check-up. Some experts advise against them because of the anxiety that the discovery of aneurysmal lesions (for which a treatment decision would rarely be taken) may provoke in the patients. Many authors, though, recommend carrying out an annual or biennial check-up including an ultrasound scan of the supra-aortic vessels and the arterial axes of the lower limbs, and a thoracic-abdominal scan with careful, low pressure injection [24]. The discovery of a previously unknown large or rapidly-expanding aneurysm requires close monitoring. For a fortuitously-discovered vascular lesion which threatens the vital prognosis, the planned surgery is thus appropriate outside of an emergency context, even though post-operative treatments are often complicated by haemorrhages or tears of the anastomoses [8].

2) Digestive complications

Most perforations occur in the sigmoid colon [26] but the small intestine can occasionally be affected (Germain DP, unpublished data). Spontaneous ruptures of the spleen and the liver have also been described [27]. There is a high risk (50%) of multiple colonic perforations and leakage from the anastomosis in case of simple segmental resection with immediate re-establishment of continuity [12,28]. The treatment of choice is therefore partial colectomy with colostomy, possibly followed by secondary re-establishment of continuity (Figure 4). Alternatively, total colectomy with ileostomy and closure of the rectal stump or ileo-rectal anastomosis may be proposed despite the young age of patients, because of the risk of recurrent colonic perforations and the scarcity of perforations of the small intestine [16]. There is a significant risk of leakage on the anastomosis.

Figure 4.

Surgical laparotomy scar following sigmoid colon perforation in a young patient presenting with vascular Ehlers-Danlos syndrome.

Mortality due to digestive perforations in patients suffering from vascular EDS is relatively low, estimated at 2% [1] and, therefore, lower than some descriptions from isolated clinical cases may indicate [29].

3) Obstetrical complications

Pregnancy can increase the likelihood of a uterine or vascular rupture in women suffering from EDS type IV (particularly during the last three months) [30]. Maternal mortality stands at around 12% [1,5,31]. The highest is the risk during labour, delivery and immediate post-partum period. Uterine haemorrhages occur frequently during the post-partum period and are sometimes only treatable by hysterectomy. The value of a caesarean carried out before the onset of labour (in order to minimise the risks related to contractions and take better control of haemostasis) [32] has not yet been the subject of a controlled study [24]. The prophylactic use of desmopressin to control primary haemostasis has been proposed [33].

4) Pleuropulmonary complications

Pneumothoraces, haemoptysis [34] and haemorrhagic cavitary lesions [35] of the pulmonary parenchyma have occurred in several patients suffering from EDS type IV [6].

5) Mitral valve prolapse

An increased frequency of mitral valve prolapse (MVP) has been reported in patients with EDS type IV [36]. However, it should be noted that this is the case in many inherited disorders of connective tissue and that the exact prevalence of MVP in the general population is unknown [7].

Aetiology

Genetics

Mode of transmission

Vascular EDS is caused by heterozygote mutations of the COL3A1 gene and is transmitted as an autosomal dominant trait [1,5,7,37].

Gene location

Type III collagen is coded by an unique gene, COL3A1, whose locus is situated on the long arm of chromosome 2, in position 2q24.3-q31 [38]. Linkage analyses have demonstrated that vascular EDS co-segregates with polymorphic markers in this locus [39]. There is no genetic heterogeneity and the polymorphic markers in the COL3A1 locus can occasionally allow the allele associated with the disease to be identified in families and can prove useful for indirect molecular diagnosis.

Physiopathology

Collagens are a family of proteins that contribute to the organisation of the extracellular matrix, comprising at least 19 proteins coded by at least 35 non-allelic genes dispersed in the genome [40]. EDS type IV is caused by a deficit of type III collagen, which belongs to the fibrillar collagens. All fibrillar collagens are homo- or heterotrimerics formed by the linking of three monomers or α chains. Type III collagen is a homotrimeric formed by the linking of three α1(III) chains, with the central part of the molecule adopting a triple-helix structure. The amino acid sequence of the triple helix is characterised by repeated glycine-X-Y sequences, where X and Y are often the amino acids proline and hydroxyproline respectively. In order to ensure correct linking of α monomers, there should be no interruption in the repetition of the glycine-X-Y triplets and the length of the triple helix should remain similar for each α chain [5].

Type III collagen is a constituent of arterial walls. Its quantitative or qualitative deficit in EDS type IV accounts for the propensity of arterial tears or dissections which characterise this illness. The walls of the digestive tract are also rich in type III collagen, which explains why digestive perforations are another frequent complication of EDS type IV [41,42].

Diagnosis

Clinical criteria (Table 2)

Table 2.

Vascular Ehlers-Danlos syndrome: Villefranche diagnostic criteria (adapted from [3]

| Major diagnosis criteria | Arterial, digestive or uterine fragility or rupture |

| Thin, translucent skin | |

| Extensive bruising | |

| Characteristic facial appearance | |

| Minor diagnosis criteria | Positive family history, sudden death in a close relative |

| Acrogeria | |

| Hypermobility of small joints | |

| Tendon and muscle rupture | |

| Talipes equinovarus (clubfoot) | |

| Early onset varicose veins | |

| Spontaneous pneumothorax or haemothorax |

Diagnosis of EDS type IV is mainly clinical and is easier when the patient is acrogeric, has a positive family history or has displayed a first instance of arterial or digestive complication.

Laboratory diagnosis

1) Biochemical diagnosis

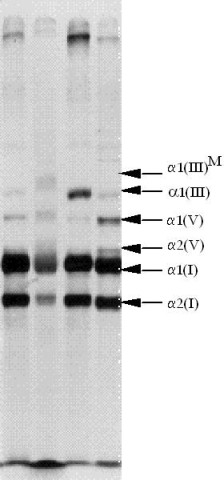

The study of the secretion of collagen III by skin fibroblasts may demonstrate a quantitative or qualitative deficit with abnormal migration of the proα1(III) chains to electrophoresis of proteins on polyacrylamide denaturant gel (Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate-Polyacrylamide Gel Electrophoresis, SDS-PAGE) (Figure 5) [37].

Figure 5.

Sodium dodecyl sulfate-PolyAcrylamide Gel Electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) analysis of collagens secretion in a patient affected with vascular EDS and a control. The band corresponding to type III collagen is indicated by α1(III). Columns 1 and 3 correspond to the supernatant culture medium of the cutaneous fibroblasts. Colums 2 and 4 correspond to cell extracts. Secretion of type III collagen in the medium is reduced in the patient (column 1) as compared to the control (column 3). Conversely, there is intracellular retention of abnormal collagen in the cell extracts of the patient (column 2) as compared to the control. In addition, the mutant collagen III has a higher molecular weight due to additional post-translational modification α1(III)M.

2) Molecular biology

The publication of the complementary DNA (cDNA) sequence of the COL3A1 gene has paved the way towards understanding of the molecular basis of EDS type IV [43-45]. Direct molecular analysis, which is difficult because of the large size of the gene and the major allelic heterogeneity, allows the mutation of the COL3A1 gene to be characterised exactly (Figure 6). EDS type IV can be caused by missense point mutations affecting the glycine residues of the triple helix [46], splicing mutations with exon skipping [47], small or large deletions [44] or haploinsuffiency [48]. Each mutation is particular to a given family [5,49].

Figure 6.

Detection of a heterozygote missense mutation (G514V) in the COL3A1 gene in a 47-year old female patient affected with Ehlers-Danlos syndrome type IV. A G to A substitution was found at nucleotide position 2042 starting from the initiation codon (ATG) of the COL3A1 gene. This nucleotide substitution alters the codon (GGT) for glycine to the codon (GTT) for valine at position 514 of the α-chain of collagen type III protein. Two electrophoregrams of the same patient are shown. (Figure courtesy of Prof. X. Jeunemaitre)

3) Histology

Optical microscopy

The observation of a skin biopsy via optical microscopy does not usually contribute a great deal but can occasionally reveal a thinned dermis, within which the groups of collagen appear sparse and/or irregular [5].

Electron microscopy

Ultrastructure study can sometimes reveal images of dilation of the granular endoplasmic reticulum of the skin fibroblasts, irregularities in the diameter of collagen fibres and an unidentified fibrino-granular substance within the extracellular matrix. Given the high number of false negatives, the absence of these images should not exclude the diagnosis EDS type IV [5].

4) Haemostasis

Haemostasis tests are normal with the possible exception of an increased bleeding time in some patients. The tendency toward haemorrhages in EDS type IV therefore appears to be due to fragility of the tissue and the capillaries, rather than a thrombocytic or plasmatic defect [50].

Differential diagnosis

In childhood, coagulation disorders and Silverman's syndrome are the most often-cited differential diagnoses, owing to the propensity for haematomas and ecchymoses in EDS type IV. In adulthood, the other Ehlers-Danlos syndromes, as well as Marfan syndrome (OMIM #154700) and Loeys-Dietz syndrome (OMIM #609192) caused by mutations in the genes TGFR1 (OMIM #190181) or TGFR2 (OMIM #190182) [51,52], and arterial tortuosity syndrome (OMIM 208050) caused by a deficit in GLUT10 [53] can sometimes pose a problem. Similarly, when no mutation of the COL3A1 gene has been identified, the possible existence of yet unidentified hereditary disorders of connective tissue causing arterial aneurysms or dissections, and therefore mimicking EDS type IV, should be considered. In contrast, we recently reported a syndrome of joint hyperlaxity, easy bruising, pelvic organs prolapses, premature rupture of the membranes and rectal bleeding associated with a non-glycine sequence variant of the COL3A1 gene (P435T) [54]. Whether non-glycine mutations of the COL3A1 gene may be responsible for a phenotype different from EDS type IV warrants further studies [54].

Management including treatment

In the absence of specific treatment for EDS type IV, medical intervention should be focused on symptomatic treatment, prophylactic measures and genetic counselling. Patients should be advised to carry with them a letter or a card (such as the European Ehlers-Danlos syndrome passport) indicating the nature of their illness, the vascular or digestive complications to which they are at risk, their blood group and the contact details of a medical practitioner [5]. Intense physical activity, scuba diving and violent sports are inadvisable. Various medications such as acetylsalicylic acid, clopidogrel and/or antivitamin K drugs interfere with platelets functions or coagulation and should therefore be avoided.

Arterial, digestive or uterine complications require immediate hospitalisation, observation in an intensive care unit and sometimes surgery [24]. Arteriograms and endoscopies are contraindicated in principle. Conservative approach is usually recommended when caring for a vascular complication in a patient suffering from EDS type IV [24]. When the vital prognosis is not at stake, therapeutic abstention with close monitoring is indeed preferable to unjustified surgery [24].

Surgery may, however, be required urgently to treat potentially fatal complications such as uncontrolled haemorrhage or a very large or rapidly-expanding aneurysm [8,24]. To optimise the chances of success, the surgeon should be informed of the diagnosis before beginning surgery. Surgical precautions include delicate and atraumatic handling of tissues. The surgeon must choose the least complex and most direct repair technique possible [16]. The arterial ligature is an excellent choice when it does not compromise the bloody supply of an organ [24]. Simple arterial repairs have been successfully carried out in some cases [8]. Serious arterial complications require arterial reconstruction with prosthetic material. Anastomoses should not be carried out with tension but strengthened by Teflon pledgets. Despite these precautions, a number of patients develop post-operative haemorrhagic complications, as well as problems relating to anastomosis of the prosthetic graft [8]. At present, the information on the use of stents to treat vascular complications of EDS type IV is insufficient. The risk of arterial rupture distantly from the point of puncture is high. In all cases, it is imperative the post-operative monitoring to be prolonged and the post-operative checks by non-invasive imaging techniques (scanners) repeated [24]. It is essential that patients suffering from EDS type IV are not offered surgical procedures that are unessential, such as stripping of varicose veins [4,55].

Pregnant women with vascular EDS should be considered at risk and receive special care [32,56,57].

Genetic counselling

Once the diagnosis has been confirmed, the opinion of a geneticist should be sought and family screening carried out. EDS type IV is a monogenic disorder, of autosomal dominant transmission [5]. Patients affected have a 50% risk of transmitting the disease to each of their children. The rate of de novo mutations is high and sporadic cases account for about half of all cases of EDS type IV. The hypothesis of recessive autosomal transmission of EDS type, still proposed in the eleventh edition of the hereditary monogenic disorders catalogue (OMIM), should be dismissed [5,7].

Prenatal diagnosis

Molecular prenatal diagnosis can be considered for families where the mutation is known. Choriocentesis or amniocentesis entail, in theory, risks linked to the obstetric procedure in couples where the woman suffers from EDS type IV. Artificial insemination with donor sperm (when the patient is male) and adoption are other options to discuss with the couple during genetic counselling.

Research prospects

The value of long-term beta blocker treatment (celiprolol) to prevent vascular complications in EDS type IV [58] is currently the subject of a controlled clinical trial (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT00190411). However, its statistical analysis should focus on verifying the definite absence of methodological bias which the inclusion of patients with erroneous diagnosis of EDS type IV would constitute.

References

- Pepin M, Schwarze U, Superti-Furga A, Byers PH. Clinical and genetic features of Ehlers-Danlos syndrome type IV, the vascular type. N Engl J Med. 2000;342:673–680. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200003093421001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byers PH. Ehlers-Danlos syndrome type IV: a genetic disorder in many guises. J Invest Dermatol. 1995;105:311–313. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12319926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beighton P, De Paepe A, Steinmann B, Tsipouras P, Wenstrup RJ. Ehlers-Danlos syndromes: revised nosology, Villefranche, 1997. Am J Med Genet. 1998;77:31–37. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-8628(19980428)77:1<31::AID-AJMG8>3.0.CO;2-O. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barabas AP. Vascular complications in the Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, with special reference to the "arterial type" or Sack's syndrome. J Cardiovasc Surg (Torino) 1972;13:160–167. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Germain DP, Herrera-Guzman Y. Vascular Ehlers-Danlos syndrome. Ann Genet. 2004;47:1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.anngen.2003.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinmann B. The Ehlers-Danlos syndromes. In: Royce PM and Steinmann B, editor. Connective Tissue and its Heritable Disorders: Molecular, Genetic, and Medical aspects. New-York, Wiley-Liss; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Germain DP. Ehlers-Danlos syndromes. Clinical, genetic and molecular aspects. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 1995;122:187–204. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oderich GS, Panneton JM, Bower TC, Lindor NM, Cherry KJ, Noel AA, Kalra M, Sullivan T, Gloviczki P. The spectrum, management and clinical outcome of Ehlers-Danlos syndrome type IV: a 30-year experience. J Vasc Surg. 2005;42:98–106. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2005.03.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karkos CD, Prasad V, Mukhopadhyay U, Thomson GJ, Hearn AR. Rupture of the abdominal aorta in patients with Ehlers-Danlos syndrome. Ann Vasc Surg. 2000;14:274–277. doi: 10.1007/s100169910047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cikrit DF, Miles JH, Silver D. Spontaneous arterial perforation: the Ehlers-Danlos specter. J Vasc Surg. 1987;5:248–255. doi: 10.1067/mva.1987.avs0050248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mattar SG, Kumar AG, Lumsden AB. Vascular complications in Ehlers-Danlos syndrome. Am Surg. 1994;60:827–831. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freeman RK, Swegle J, Sise MJ. The surgical complications of Ehlers-Danlos syndrome. Am Surg. 1996;62:869–873. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cikrit DF, Glover JR, Dalsing MC, Silver D. The Ehlers-Danlos specter revisited. Vasc Endovascular Surg. 2002;36:213–217. doi: 10.1177/153857440203600309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergqvist D. Ehlers-Danlos type IV syndrome. A review from a vascular surgical point of view. Eur J Surg. 1996;162:163–170. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Habib K, Memon MA, Reid DA, Fairbrother BJ. Spontaneous common iliac arteries rupture in Ehlers-Danlos syndrome type IV: report of two cases and review of the literature. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2001;83:96–104. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Germain DP. Clinical and genetic features of vascular Ehlers-Danlos syndrome. Ann Vasc Surg. 2002;16:391–397. doi: 10.1007/s10016-001-0229-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hosaka A, Miyata T, Shigematsu H, Deguchi JO, Kimura H, Nagawa H, Sato O, Sakimoto T, Mochizuki T. Spontaneous mesenteric hemorrhage associated with Ehlers-Danlos syndrome. J Gastrointest Surg. 2006;10:583–585. doi: 10.1016/j.gassur.2005.07.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schievink WI, Limburg M, Oorthuys JW, Fleury P, Pope FM. Cerebrovascular disease in Ehlers-Danlos syndrome type IV. Stroke. 1990;21:626–632. doi: 10.1161/01.str.21.4.626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- North KN, Whiteman DA, Pepin MG, Byers PH. Cerebrovascular complications in Ehlers-Danlos syndrome type IV. Ann Neurol. 1995;38:960–964. doi: 10.1002/ana.410380620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schievink WI. Cerebrovascular Involvement in Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome. Curr Treat Options Cardiovasc Med. 2004;6:231–236. doi: 10.1007/s11936-996-0018-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chuman H, Trobe JD, Petty EM, Schwarze U, Pepin M, Byers PH, Deveikis JP. Spontaneous direct carotid-cavernous fistula in Ehlers-Danlos syndrome type IV: two case reports and a review of the literature. J Neuroophthalmol. 2002;22:75–81. doi: 10.1097/00041327-200206000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desal HA, Toulgoat F, Raoul S, Guillon B, Bommard S, Naudou-Giron E, Auffray-Calvier E, de Kersaint-Gilly A. Ehlers-Danlos syndrome type IV and recurrent carotid-cavernous fistula: review of the literature, endovascular approach, technique and difficulties. Neuroradiology. 2005;47:300–304. doi: 10.1007/s00234-005-1378-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Majersik JJ, Skalabrin EJ. Single-gene stroke disorders. Semin Neurol. 2006;26:33–48. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-933307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Germain DP. The vascular Ehlers-Danlos syndrome. Curr Treat Options Cardiovasc Med. 2006;8:121–127. doi: 10.1007/s11936-006-0004-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slingenberg EJ. Complications during intravascular diagnostic manipulations in the Ehlers-Danlos syndrome. Neth J Surg. 1980;32:56–58. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinnane J, Priebe C, Caty M, Kuppermann N. Perforation of the colon in an adolescent girl. Pediatr Emerg Care. 1995;11:230–232. doi: 10.1097/00006565-199508000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris SC, Slater DN, Austin CA. Fatal splenic rupture in Ehlers-Danlos syndrome. Postgrad Med J. 1985;61:259–260. doi: 10.1136/pgmj.61.713.259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berney T, La Scala G, Vettorel D, Gumowski D, Hauser C, Frileux P, Ambrosetti P, Rohner A. Surgical pitfalls in a patient with type IV Ehlers-Danlos syndrome and spontaneous colonic rupture. Report of a case. Dis Colon Rectum. 1994;37:1038–1042. doi: 10.1007/BF02049321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sparkman RS. Ehlers-Danlos syndrome type IV: dramatic, deceptive, and deadly. Am J Surg. 1984;147:703–704. doi: 10.1016/0002-9610(84)90148-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peaceman AM, Cruikshank DP. Ehlers-Danlos syndrome and pregnancy: association of type IV disease with maternal death. Obstet Gynecol. 1987;69:428–431. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pope FM, Nicholls AC. Pregnancy and Ehlers-Danlos syndrome type IV. Lancet. 1983;1:249–250. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(83)92631-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lurie S, Manor M, Hagay ZJ. The threat of type IV Ehlers-Danlos syndrome on maternal well-being during pregnancy: early delivery may make the difference. J Obstet Gynaecol. 1998;18:245–248. doi: 10.1080/01443619867416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stine KC, Becton DL. DDAVP therapy controls bleeding in Ehlers-Danlos syndrome. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 1997;19:156–158. doi: 10.1097/00043426-199703000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yost BA, Vogelsang JP, Lie JT. Fatal hemoptysis in Ehlers-Danlos syndrome. Old malady with a new curse. Chest. 1995;107:1465–1467. doi: 10.1378/chest.107.5.1465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herman TE, McAlister WH. Cavitary pulmonary lesions in type IV Ehlers-Danlos syndrome. Pediatr Radiol. 1994;24:263–265. doi: 10.1007/BF02015451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaffe AS, Geltman EM, Rodey GE, Uitto J. Mitral valve prolapse: a consistent manifestation of type IV Ehlers- Danlos syndrome. The pathogenetic role of the abnormal production of type III collagen. Circulation. 1981;64:121–125. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.64.1.121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pope FM, Narcisi P, Nicholls AC, Germain DP, Pals G, Richards AJ. COL3A1 mutations cause variable clinical phenotypes including acrogeria and vascular rupture. Br J Dermatol. 1996;135:163–181. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.1996.d01-971.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emanuel BS, Cannizzaro LA, Seyer JM, Myers JC. Human a1(III) and a 2(V) procollagen genes are located on the long arm of chromosome 2. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA. 1985;82:3385–3389. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.10.3385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicholls AC, De Paepe A, Narcisi P, Dalgleish R, De Keyser F, Matton M, Pope FM. Linkage of a polymorphic marker for the type III collagen gene (COL3A1) to atypical autosomal dominant Ehlers-Danlos syndrome type IV in a large Belgian pedigree. Hum Genet. 1988;78:276–281. doi: 10.1007/BF00291676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vuorio E, de Combrugghe B. The family of collagen genes. Annual Review of Biochemistry. 1990;59:837–872. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.59.070190.004201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pope FM, Martin GR, Lichtenstein JR, Penttinen R, Gerson B, Rowe DW, McKusick VA. Patients with Ehlers-Danlos syndrome type IV lack type III collagen. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1975;72:1314–1316. doi: 10.1073/pnas.72.4.1314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byers PH, Holbrook KA, Barsh GS, Smith LT, Bornstein P. Altered secretion of type III procollagen in a form of type IV Ehlers- Danlos syndrome. Biochemical studies in cultured fibroblasts. Lab Invest. 1981;44:336–341. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richards AJ, Lloyd JC, Ward PN, De Paepe A, Narcisi P, Pope FM. Characterisation of a glycine to valine substitution at amino acid position 910 of the triple helical region of type III collagen in a patient with Ehlers-Danlos syndrome type IV. J Med Genet. 1991;28:458–463. doi: 10.1136/jmg.28.7.458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richards AJ, Lloyd JC, Narcisi P, Ward PN, Nicholls AC, De Paepe A, Pope FM. A 27-bp deletion from one allele of the type III collagen gene (COL3A1) in a large family with Ehlers-Danlos syndrome type IV. Hum Genet. 1992;88:325–330. doi: 10.1007/BF00197268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Narcisi P, Wu Y, Tromp G, Earley JJ, Richards AJ, Pope FM, Kuivaniemi H. Single base mutation that substitutes glutamic acid for glycine 1021 in the COL3A1 gene and causes Ehlers-Danlos syndrome type IV. Am J Med Genet. 1993;46:278–283. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.1320460308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richards A, Narcisi P, Lloyd J, Ferguson C, Pope FM. The substitution of glycine 661 by arginine in type III collagen produces mutant molecules with different thermal stabilities and causes Ehlers-Danlos syndrome type IV. J Med Genet. 1993;30:690–693. doi: 10.1136/jmg.30.8.690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richards AJ, Narcisi P, Ferguson C, Cobben JM, Pope FM. Two new mutations affecting the donor splice site of COL3A1 IVS37 and causing skipping of exon 37 in patients with Ehlers-Danlos syndrome type IV. Hum Mol Genet. 1994;3:1901–1902. doi: 10.1093/hmg/3.10.1901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwarze U, Schievink WI, Petty E, Jaff MR, Babovic-Vuksanovic D, Cherry KJ, Pepin M, Byers PH. Haploinsufficiency for one COL3A1 allele of type III procollagen results in a phenotype similar to the vascular form of Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, Ehlers-Danlos syndrome type IV. Am J Hum Genet. 2001;69:989–1001. doi: 10.1086/324123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe A, Kosho T, Wada T, Sakai N, Fujimoto M, Fukushima Y, Shimada T. Genetic aspects of the vascular type of Ehlers-Danlos syndrome (vEDS, EDSIV) in Japan. Circ J. 2007;71:261–265. doi: 10.1253/circj.71.261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Paepe A, Malfait F. Bleeding and bruising in patients with Ehlers-Danlos syndrome and other collagen vascular disorders. Br J Haematol. 2004;127:491–500. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2004.05220.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loeys BL, Chen J, Neptune ER, Judge DP, Podowski M, Holm T, Meyers J, Leitch CC, Katsanis N, Sharifi N, Xu FL, Myers LA, Spevak PJ, Cameron DE, De Backer J, Hellemans J, Chen Y, Davis EC, Webb CL, Kress W, Coucke P, Rifkin DB, De Paepe AM, Dietz HC. A syndrome of altered cardiovascular, craniofacial, neurocognitive and skeletal development caused by mutations in TGFBR1 or TGFBR2. Nat Genet. 2005;37:275–281. doi: 10.1038/ng1511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loeys BL, Schwarze U, Holm T, Callewaert BL, Thomas GH, Pannu H, De Backer JF, Oswald GL, Symoens S, Manouvrier S, Roberts AE, Faravelli F, Greco MA, Pyeritz RE, Milewicz DM, Coucke PJ, Cameron DE, Braverman AC, Byers PH, De Paepe AM, Dietz HC. Aneurysm syndromes caused by mutations in the TGF-beta receptor. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:788–798. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa055695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coucke PJ, Willaert A, Wessels MW, Callewaert B, Zoppi N, De Backer J, Fox JE, Mancini GM, Kambouris M, Gardella R, Facchetti F, Willems PJ, Forsyth R, Dietz HC, Barlati S, Colombi M, Loeys B, De Paepe A. Mutations in the facilitative glucose transporter GLUT10 alter angiogenesis and cause arterial tortuosity syndrome. Nat Genet. 2006;38:452–457. doi: 10.1038/ng1764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Germain DP. A non-glycine sequence variant (P435T) of the COL3A1 gene associated with an autosomal dominant syndrome of joint hyperlaxity, easy bruising, pelvic organs prolapses, premature rupture of the membranes and rectal bleeding. Am J Hum Genet. 2006. p. 347.

- Beighton P, Horan FT. Surgical aspects of the Ehlers-Danlos syndrome. A survey of 100 cases. Br J Surg. 1969;56:255–259. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800560404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brighouse D, Guard B. Anaesthesia for caesarean section in a patient with Ehlers-Danlos syndrome type IV. Br J Anaesth. 1992;69:517–519. doi: 10.1093/bja/69.5.517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bjorck M, Pigg M, Kragsterman B, Bergqvist D. Fatal Bleeding following Delivery: A Manifestation of the Vascular Type of Ehlers-Danlos' Syndrome. Gynecol Obstet Invest. 2006;63:173–175. doi: 10.1159/000097659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boutouyrie P, Germain DP, Fiessinger JN, Laloux B, Perdu J, Laurent S. Increased carotid wall stress in vascular Ehlers-Danlos syndrome. Circulation. 2004;109:1530–1535. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000121741.50315.C2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicholls AC, Oliver JE, McCarron S, Harrison JB, Greenspan DS, Pope FM. An exon skipping mutation of a type V collagen gene (COL5A1) in Ehlers- Danlos syndrome. J Med Genet. 1996;33:940–946. doi: 10.1136/jmg.33.11.940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Paepe A, Nuytinck L, Hausser I, Anton-Lamprecht I, Naeyaert JM. Mutations in the COL5A1 gene are causal in the Ehlers-Danlos syndromes I and II. Am J Hum Genet. 1997;60:547–554. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burch GH, Gong Y, Liu W, Dettman RW, Curry CJ, Smith L, Miller WL, Bristow J. Tenascin-X deficiency is associated with Ehlers-Danlos syndrome. Nat Genet. 1997;17:104–108. doi: 10.1038/ng0997-104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schalkwijk J, Zweers MC, Steijlen PM, Dean WB, Taylor G, van Vlijmen IM, van Haren B, Miller WL, Bristow J. A recessive form of the Ehlers-Danlos syndrome caused by tenascin-X deficiency. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:1167–1175. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa002939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zweers MC, Bristow J, Steijlen PM, Dean WB, Hamel BC, Otero M, Kucharekova M, Boezeman JB, Schalkwijk J. Haploinsufficiency of TNXB is associated with hypermobility type of Ehlers-Danlos syndrome. Am J Hum Genet. 2003;73:214–217. doi: 10.1086/376564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pousi B, Hautala T, Heikkinen J, Pajunen L, Kivirikko KI, Myllyla R. Alu-Alu recombination results in a duplication of seven exons in the lysyl hydroxylase gene in a patient with the type VI variant of Ehlers-Danlos syndrome. Am J Hum Genet. 1994;55:899–906. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole WG, Chan D, Chambers GW, Walker ID, Bateman JF. Deletion of 24 amino acids from the pro-alpha 1(I) chain of type I procollagen in a patient with the Ehlers-Danlos syndrome type VII. J Biol Chem. 1986;261:5496–5503. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weil D, Bernard M, Combates N, Wirtz MK, Hollister DW, Steinmann B, Ramirez F. Identification of a mutation that causes exon skipping during collagen pre-mRNA splicing in an Ehlers-Danlos syndrome variant. J Biol Chem. 1988;263:8561–8564. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colige A, Sieron AL, Li SW, Schwarze U, Petty E, Wertelecki W, Wilcox W, Krakow D, Cohn DH, Reardon W, Byers PH, Lapiere CM, Prockop DJ, Nusgens BV. Human Ehlers-Danlos syndrome type VII C and bovine dermatosparaxis are caused by mutations in the procollagen I N-proteinase gene. Am J Hum Genet. 1999;65:308–317. doi: 10.1086/302504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okajima T, Fukumoto S, Furukawa K, Urano T. Molecular basis for the progeroid variant of Ehlers-Danlos syndrome. Identification and characterization of two mutations in galactosyltransferase I gene. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:28841–28844. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.41.28841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rahman N, Dunstan M, Teare MD, Hanks S, Douglas J, Coleman K, Bottomly WE, Campbell ME, Berglund B, Nordenskjold M, Forssell B, Burrows N, Lunt P, Young I, Williams N, Bignell GR, Futreal PA, Pope FM. Ehlers-Danlos syndrome with severe early-onset periodontal disease (EDS-VIII) is a distinct, heterogeneous disorder with one predisposition gene at chromosome 12p13. Am J Hum Genet. 2003;73:198–204. doi: 10.1086/376416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheen VL, Jansen A, Chen MH, Parrini E, Morgan T, Ravenscroft R, Ganesh V, Underwood T, Wiley J, Leventer R, Vaid RR, Ruiz DE, Hutchins GM, Menasha J, Willner J, Geng Y, Gripp KW, Nicholson L, Berry-Kravis E, Bodell A, Apse K, Hill RS, Dubeau F, Andermann F, Barkovich J, Andermann E, Shugart YY, Thomas P, Viri M, Veggiotti P, Robertson S, Guerrini R, Walsh CA. Filamin A mutations cause periventricular heterotopia with Ehlers-Danlos syndrome. Neurology. 2005;64:254–262. doi: 10.1212/01.WNL.0000149512.79621.DF. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]